Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: Exploring Ecosocial Work Discourses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What ecosocial work discourses related to youth empowerment can be identified?

- (2)

- What driving forces and circumstances are there for ecosocial work-related discourses with/for youth?

- (3)

- What implications do the findings have in terms of research and practice of ecosocial work in promoting youth wellbeing and work-life capacities within the context of sustainable development?

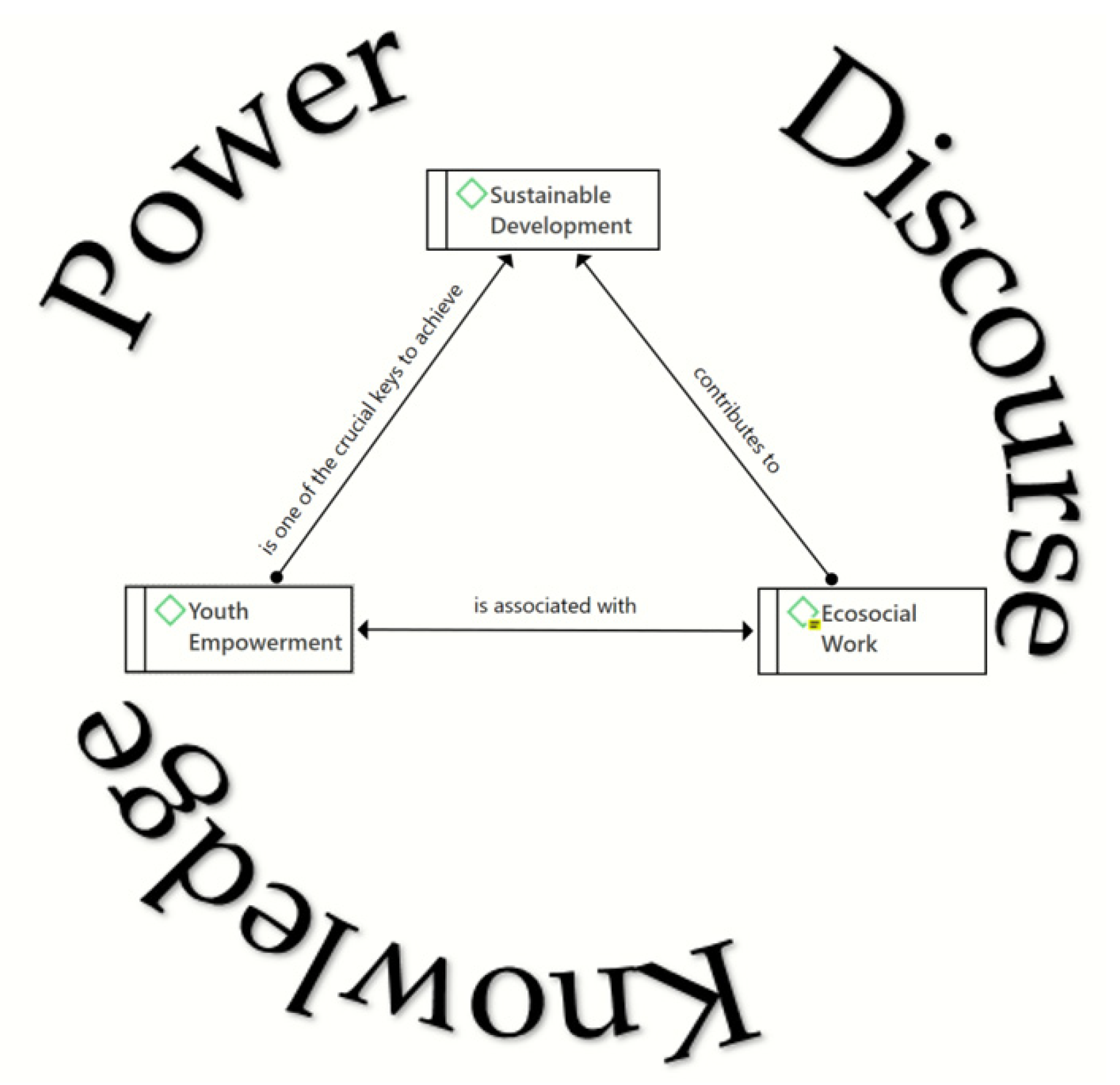

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Recruitment

3.2. Data Gathering and Handling

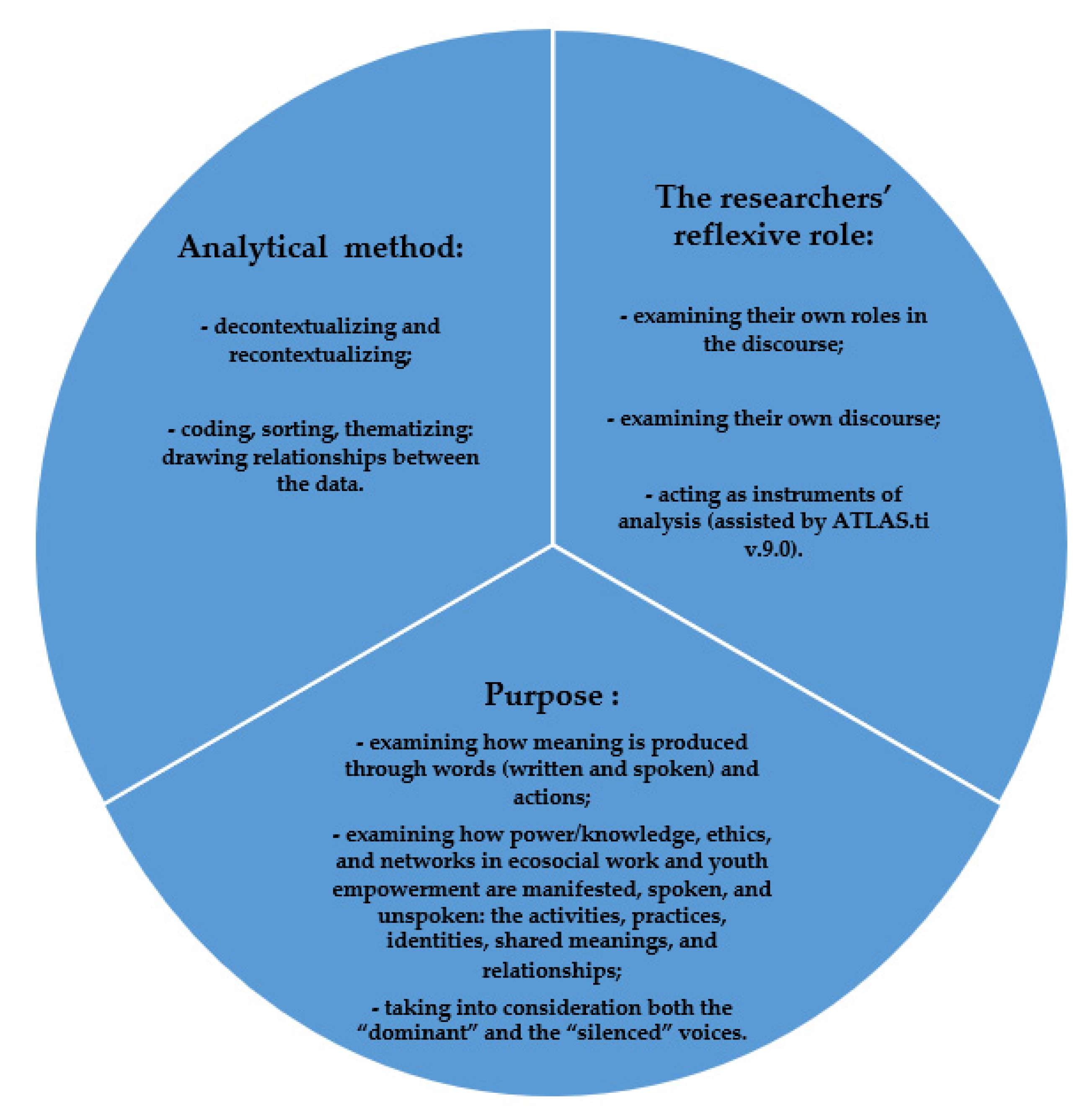

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Knowledge/Awareness

4.1.1. Sustainable Development

Sustainability is very central for the future of our city, for the municipality, and for the world—and I’m talking about the economic, ecological, about the environment and climate, and social sustainability, the good life for all. …/…when we’re working with sustainability, we work internally, meaning we work together within the municipal organizations and we work externally towards the municipal citizens.(#1)

[After a long pause] I don’t really know [what sustainability is, what SD is, or what the pillars are]. [Upon being shown a diagram summarizing SD and the SDGs] No, I have never seen these before.(#9)

4.1.2. Interrelation between Social and Ecological Dimensions

- climate refugees, how the planet’s temperature/climate can affect humans’ social behavior in one way or another, and how humans affect the climate (#1);

- bad planning of a neighborhood with limited green areas, contributing to less social space to interact, leading to social isolation/exclusion (#2, #14);

- the relationship between public transportation, socioeconomic status, and segregation/isolation (#3);

- high houses/apartments in front of each other blocking the sunlight and contributing to a lower level of feeling of wellness (#14);

- overcrowded apartments due to socioeconomic situations potentially leading to the need to find a “second living room”, which could be a youth center, or outdoor hanging around in the neighborhood (#19).

There is a development project in locality X, and both the social perspective and the environmental perspective are important and should be taken into consideration, e.g., it should take into account the emissions when building, or how to create a safe environment so that children can be there without being hit by the traffic, there should be areas to ride a bicycle, and to have green spaces between the buildings, because green spaces are important both for health and for the environmental perspective. These two aspects go hand-in-hand in a sustainable city development perspective.(#1)

…There are some certain aspects that we can simplify, e.g., public transport. What does it say about the socio-economy factor: who uses the most public transport? That is a simple example, a complex and difficult to explain… in the future we would get “climate refugees”. There we can see the relationship, how the planet’s temperature/climate can affect humans’ social behaviour in one way or another, and how humans affect the climate.(#1)

Many of the youth we work with, are alienated socioeconomically, that can be seen in how the neighborhood looks like—people live in overcrowded apartments, there is exclusion, and there are young people who even live outside this exclusion.(#17)

4.1.3. Ecosocial Work with Youth

Organization W (which is a youth center) in locality Z has also worked with the youth in the neighborhood on a project related to sustainability, where in 2018 the youth in this locality composed a song called “Planera, Sortera & Organisera” [Planning, Sorting & Organizing] about the importance of sorting out their household waste and avoiding littering, as an action to keep the Earth alive.(#6)

In ESD it is important to promote an interdisciplinary perspective of SD and not isolate the three pillars, even though there is a tendency for that, e.g., the social sciences teacher focuses mainly only on social sustainability…//… We have a “whole school approach”, we aim for the students to achieve “action skills”—we can’t just teach and tell [the students] about things, but the students need to get the opportunity to practice. One learns better by doing. Action skills have a lot to do with attitudes, knowledge, and values, but also with practicing ways to contribute.(#4)

4.2. Youth Empowerment

We have initiated “youth ambassadors” to keep the nearby environment clean; six youths, three nights a week, patrolling the neighborhood and making sure that staircases in the buildings are clean, and picking up trash when necessary…//when they want to do an activity, we ask who wants to take the responsibility and let them do it under our supervision.(#9)

We must think about how to get and motivate these young people, how we could get them to vote…//…My starting point was that the young people themselves would know best; they would have the best idea of what was working or not in reaching this group…//… we employed young people to reach this group as “young vote ambassadors”. We let them come up with ideas with how to reach this target group. The strategy was to let the young people come up with the strategy. Young people are the experts on themselves.(#2)

The most natural thing about “preventative work” [such as their work] is that it’s about social sustainability, it’s about creating… not changes, but maybe creating interventions and small contributions which can help make the necessary changes to be sustainable in the long run.(#12)

Within the municipality, there is a “Social Sustainability Program” and an “Environmental Strategy Program”, and we see this as a wrong step by the municipality—we have expressed this to the municipality, but the municipality chose to do it anyway. We can’t isolate social sustainability from environmental sustainability; it makes it more difficult to see SD as a whole.(#4)

Our work is based on the mission assigned to us by the politicians …//… It depends on what kind of missions we get.(#2)

For us, the ESD, we work on the basis of the “Environmental Strategy Program” (Miljöstrategisk program) established by the city council of the municipality—but above all, it’s based on the governing documents of schools, and the curriculum, which sets a framework for ESD.(#5)

4.3. Circumstances for SD Work and Ecosocial Discourse with Youth

The public sector doesn’t really follow this relationship between the ecosocial aspects, as we are very much controlled by New Public Management; we have to measure as much as possible, which means it should be measurable. But these kinds of questions on ecosocial issues are more qualitative questions, about people’s feelings, values, etc.—we aren’t interested in making diagrams. There are of course relations between environmental and social questions, but in some aspects we need to distinguish them, so that things are manageable.(#2)

We collaborate with many different actors, including a youth center located in the marginalized neighborhood, and this youth center does a lot of work with sustainability questions [with the youth in the neighborhood]. The youth were asked once, what a sustainable neighborhood would look like, and they came up with ideas of how they could cycle around the neighborhood if we as the housing company provided rental bicycles in each building’s entrance, and they could rent the bicycles with their key cards…//…(#6)

The municipal management is very segmented…//… The segmentation and specialization create difficulties, as it means that we need to talk to different people, different leaders, there are different fund allocations, which makes things slow//…It would be wonderful if there could be a “hållbarhets avdelning” (Department of Sustainability) which covers both strategic and operative responsibility for sustainability work in the municipality.(#3)

5. Discussion

Contributions and Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matthies, A.-L. The Conceptualization of Ecosocial Transition. In The Ecosocial Transition of Societies: The Contribution of Social Work and Social Policy; Matthies, A.-L., Närhi, K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.; Kim, J. UN and SDGs: A Handbook for Youth. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/resources/un-and-sdgs-handbook-youth (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Rocha, E.M. A Ladder of Empowerment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1997, 17, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, A.; Rappaport, J. Empowerment, Wellness and the Politics of Development. In The Promotion of Wellness in Children and Adolescents; Cicchetti, D., Rappaport, J., Sandler, I., Weissberg, R.P., Eds.; Child Welfare League of America Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 59–99. ISBN 0878687912. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, A.C.; Seidman, E. Empowerment Theory and Youth. In Encyclopedia of Applied Developmental Science; Fisher, C.B., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 401–403. ISBN 0-7619-2820-0. [Google Scholar]

- SDSN-Youth. Youth Solutions Report; SDSN-Youth: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Keitsch, M. Structuring Ethical Interpretations of the Sustainable Development Goals—Concepts, Implications and Progress. Sustainability 2018, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torpman, O.; Röcklinsberg, H. Reinterpreting the SDGs: Taking Animals into Direct Consideration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ife, J. Radically Transforming Human Rights for Social Work Practice. Available online: https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/9560 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development: History. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-84407-016-9. [Google Scholar]

- Svenska Unescorådet. ESD for 2030. Available online: https://unesco.se/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ESD-for-2030.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; ISBN 9789231003943. [Google Scholar]

- Bexell, S.M.; Sparks, J.L.D.; Tejada, J.; Rechkemmer, A. An Analysis of Inclusion Gaps in Sustainable Development Themes: Findings from A Review of Recent Social Work Literature. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Hiswåls, A.-S.; Thalén, P.; Turunen, P. Urban Green Commons for Socially Sustainable Cities and Communities. Nord. Soc. Work Res. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, S.; Turunen, P. Samhällsförändringar som Utmanar. In Samhällsarbete: Aktörer, Arenor och Perspektiv; Sjöberg, S., Turunen, P., Eds.; Studentlitteratur AB: Lund, Sweden, 2018; pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, J.L.; Checkoway, B. Young People as Competent Community Builders: A Challenge to Social Work. Soc. Work 1998, 43, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusler, T.; Krings, A.; Hernández, M. Integrating Youth Participation and Ecosocial Work: New Possibilities to Advance Environmental and Social Justice. J. Community Pract. 2019, 27, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krings, A.; Victor, B.G.; Mathias, J.; Perron, B.E. Environmental Social Work in the Disciplinary Literature, 1991–2015. Int. Soc. Work 2020, 63, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, M.; Rinkel, M.; Kumar, P. Co-Creating a “Sustainable New Normal” for Social Work and Beyond: Embracing an Ecosocial Worldview. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truell, R. News from Our Societies–IFSW: Social Work and Co-building A New Eco-social World. Int. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Närhi, K. The Eco-Social Approach in Social Work and the Challenges to the Expertise of Social Work; University of Jyväskylän: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Närhi, K.; Matthies, A.-L. The Ecosocial Approach in Social Work as A Framework for Structural Social Work. Int. Soc. Work 2018, 61, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, J. The place of social work in sustainable development: Towards ecosocial practice. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2012, 21, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boetto, H. A Transformative Eco-Social Model: Challenging Modernist Assumptions in Social Work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turunen, P.; Matthies, A.-L.; Närhi, K.; Boeck, T.; Albers, S. Practical Models and Theoretical Findings in Combating Social Exclusion. In The Eco-Social Approach in Social Work; Matthies, A.-L., Närhi, K., Ward, D., Eds.; SoPhi, University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2001; pp. 108–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, K. A Philosophy of Social Work beyond the Anthropocene. In Post-Anthropocentric Social Work Critical Posthuman and New Materialist Perspectives; Bozalek, V., Pease, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 58–67. ISBN 978-0-429-32998-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay, S.; Boddy, J. Environmental Social Work: A Concept Analysis. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozalek, V.; Pease, B. Towards Post-Anthropocentric Social Work. In Post-Anthropocentric Social Work Critical Posthuman and New Materialist Perspectives; Bozalek, V., Pease, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, S. What Comes after the Subject? Towards a Critical Posthumanist Social Work. In Post-Anthropocentric Social Work Critical Posthuman and New Materialist Perspectives; Bozalek, V., Pease, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 19–31. ISBN 978-0-429-32998-2. [Google Scholar]

- Susen, S. Reflections on the (Post-) Human Condition: Towards New Forms of Engagement with the World. Soc. Epistemol. 2022, 36, 63–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFSW Global Definition of Social Work. Available online: www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar. Hållbar Socialtjänst—En Ny Socialtjänstlag SOU 2020:47; Elanders Sverige AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, P. Samhällsarbete i Norden Diskurser och Praktiker i Omvandling; Växsjö University Press: Växjö, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, J.H. Servants of A ‘Sinking Titanic’ or Actors of Change? Contested Identities of Social Workers in Sweden. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2019, 22, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuadra, C.B. Disaster Social Work in Sweden: Context, Practice and Challenges in An International Perspective; University of Malmö: Malmö, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaree, K.; Sjöberg, S.; Turunen, P. Ecosocial Change and Community Resilience: The Case of “Bönan” in Glocal Transition. J. Community Pract. 2019, 27, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rambaree, K. Environmental Social Work: Implications for Accelerating the Implementation of Sustainable Development in Social Work Curricula. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar. Ju Förr Desto Bättre—Vägar till En Förebyggande Socialtjänst: Delbetänkande av Utredningen Framtidens Socialtjänst; Statens Offentliga Utredningar: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaree, K.; Faxelid, E. Considering Abductive Thematic Network Analysis with ATLAS.ti 6.2. In Advancing Research Methods with New Media Technologies; Sappleton, N., Ed.; IGI Global: Hersley, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 170–186. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R. Social Work and Empowerment; Macmillan Press, Ltd.: London, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-0-333-65809-3. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Seabury Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, L.B.; Parra-Medina, D.B.; Hilfinger-Messias, D.K.; McLoughlin, K. Toward a Critical Social Theory of Youth Empowerment. J. Community Pract. 2008, 14, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, J. Terms of Empowerment/Exemplars of Prevention: Toward a Theory for Community Psychology. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1987, 15, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.M.; Speers, M.A.; McLeroy, K.; Fawcett, S.; Kegler, M.; Parker, E.; Smith, S.R.; Sterling, T.D.; Wallerstein, N. Identifying and Defining the Dimensions of Community Capacity to Provide a Basis for Measurement. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 258–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Rappaport, J. Citizen Participation, Perceived Control, and Psychological Empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1988, 16, 725–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkler, M.; Wallerstein, N. Improving Health through Community Organization and Community Building: Perspectives from Health Education and Social Work. In Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare; Minkler, M., Ed.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 37–58. ISBN 978-0-8135-5314-6. [Google Scholar]

- Maton, K.I. Empowering Community Settings: Agents of Individual Development, Community Betterment, and Positive Social Change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, S.; Rambaree, K.; Jojo, B. Collective Empowerment: A Comparative Study of Community Work in Mumbai and Stockholm. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2015, 24, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Psychological Empowerment: Issues and Illustrations. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment Theory: Psychological, Organizational and Community Levels of Analysis. In Handbook of Community Psychology; Rappaport, J., Seidman, E., Eds.; Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 46–63. ISBN 978-1-4615-4193-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, C.; Eastman-Mueller, H.; Barbich, N. Empowering Change Agents: Youth Organizing Groups as Sites for Sociopolitical Development. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 63, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.J. Reciprocal Empowerment for Civil Society Peacebuilding: Sharing Lessons between the Korean and Northern Ireland Peace Processes Lessons between the Korean and Northern Ireland Peace Processes. Globalizations 2022, 19, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlington, P.S.E.; Mulvaney, B.M. Women, Power, and Ethnicity: Working toward Reciprocal Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 9781315865218. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-394-71106-8. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 2nd ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 9781444334067. [Google Scholar]

- Pease, B. Rethinking Empowerment: Emancipatory Practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2002, 32, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M.; Gros, F.; Ewald, F.; Fontana, A. The Government of Self and Others: Lectures at the Collège de France 1982–1983; Gros, F., Ewald, F., Fontana, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 285–297. ISBN 978-0-230-27473-0. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, T.H.; MacEachen, E. Foucauldian Discourse Analysis: Moving Beyond a Social Constructionist Analytic. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977; Gordon, C., Ed.; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 0394513576. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 0394417755. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R. Empowerment, Participation and Social Work, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-137-05053-3. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, B.; Fook, J. Reinventing Social Work. In Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education; Ife, J., Leitman, S., Murphy, P., Eds.; AASWWE: Perth, WA, Australia, 1994; pp. 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S.; Fook, J.; Pease, B. Empowerment: The Modern Social Work Concept Par Excellence. In Transforming Social Work Practice: Postmodern Critical Perspectives; Pease, B., Fook, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 150–160. ISBN 9780203164969. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Knowledge Management as A Doughnut: Shaping Your Knowledge Strategy through Communities of Practice. Ivey Bus. J. 2004, 68, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, J. Positioning Language and Identity. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity; Preece, S., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 34–49. ISBN 9780367353896. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinert, S.; Horton, R. Adolescent Health and Wellbeing: A Key to A Sustainable Future. Lancet 2016, 387, 2355–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Närhi, K.; Matthies, A.-L. What is the Ecological (Self-)Consciousness of Social Work? Perspectives on the Relationship between Social Work and Ecology. In The Eco-Social Approach in Social Work; Matthies, A.-L., Närhi, K., Ward, D., Eds.; SoPhi, University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2001; pp. 16–53. ISBN 9-51-39-0914-X. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm, I.; Matthies, A.-L.; Hirvilammi, T.; Närhi, K. Combining Labour Market and Unemployment Policies with Environmental Sustainability? A Cross-national Study on Ecosocial Innovations. J. Int. Comp. Soc. Policy 2020, 36, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, I. Heat, Greed and Human Need: Climate Change, Capitalism and Sustainable Wellbeing; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-78536-510-2. [Google Scholar]

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S.; Ljung, R.; Eriksson, F.; Sjöberg, S. Urban Commons and Collective Action to Address Climate Change. Soc. Incl. 2022, 10, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetenskapsrådet. Good Research Practcie; Vetenskapsrådet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Högskolan i Gävle. Policy för Personuppgiftshantering. Available online: https://www.hig.se/download/18.7718b93f16330009c5619296/1527257182612/Policyförpersonuppgiftshantering.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Etikprovningsmyndigheten. Vad Säger Lagen? Available online: https://etikprovningsmyndigheten.se/for-forskare/vad-sager-lagen/ (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Awuzie, B.O.; Mcdermott, P. An Abductive Approach to Qualitative Built Environment Research: A Viable System Methodological Exposé Article Information. Qual. Res. J. 2017, 17, 356–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-19-958805-3. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781412972123. [Google Scholar]

- Gävle Kommun. Miljöarbete. Available online: https://www.gavle.se/kommunens-service/kommun-och-politik/samarbeten-projekt-och-sarskilda-satsningar/miljostrategiskt-program/ (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Gävle Kommun. Miljöstrategiskt Program 2.0; Gävle Kommun: Gävle, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- SCB. Folkmängd efter Region, Ålder och år. Available online: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101A/BefolkningNy/table/tableViewLayout1/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Kolada. Arbetslöshet 16–24 år, Årsmedelvärde. Available online: https://www.kolada.se/verktyg/fri-sokning/?kpis=166009&years=30198,30197,30196&municipals=16551,16776&rows=municipal,kpi&visualization=bar-chart (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Rambaree, K. Abductive Thematic Network Analysis (ATNA) Using ATLAS-ti. In Innovative Research Methodologies in Management. Volume I: Philosophy, Measurement and Modelling; Moutinho, L., Sokele, M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 61–86. ISBN 978-3-319-64394-6. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781847875815. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Ayllon, M.; Walkerdine, V. Foucauldian Discourse Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology; Willig, C., Rogers, W.S., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2017; pp. 110–123. ISBN 9781526405555. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, I. Discourse Dynamics (Psychology Revivals): Critical Analysis for Social and Individual Psychology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781134549948. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, P. Foucauldian Discourse Analysis in Psychology: Reflecting on A Hybrid Reading of Foucault when Researching “Ethical Subjects”. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014, 11, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, D. Foucault, Psychology and the Analytics of Power: Critical Theory and Practice in Psychology and the Human Sciences; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-230-59232-2. [Google Scholar]

- Seal, A. Thematic Analysis. In Researching Social Life; Gilbert, N., Stoneman, P., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; pp. 444–458. ISBN 9781473944220. [Google Scholar]

- Karmugilan, K.; Pachayappan, M. Sustainable Manufacturing with Green Environment: An Evidence from Social Media. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 22, 1878–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The Use of Pleasure: Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 2, ISBN 0394751221. [Google Scholar]

- Gävle Kommun. Lärande för Hållbar Utveckling—LHU. Available online: https://www.gavle.se/kommunens-service/kommun-och-politik/samarbeten-projekt-och-sarskilda-satsningar/larande-for-hallbar-utveckling-lhu/ (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Boehm, A.; Staples, L.H. Empowerment: The Point of View of Consumers. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2004, 85, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzhaky, H.; York, A.S. Sociopolitical Control and Empowerment: An Extended Replication. J. Community Psychol. 2000, 28, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, W.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Krasniqi, F.; Blagden, J. The State of Our Social Fabric and Geography. Available online: https://www.ippr.org/environment-and-justice (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Ostrom, E.; Webb, J.; Stone, L.; Murphy, L.; Hunter, J. The Climate Commons: How Communities Can Thrive in A Climate Changing World; Institute for Public Policy Research: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, M.H. Empowerment in Terms of Theoretical Perspectives: Exploring A Typology of the Process and Components across Disciplines. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 34, 523–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, L.H. Powerful Ideas about Empowerment. Administration in Social Work. Adm. Soc. Work 1990, 14, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parpart, J.L.; Rai, S.M.; Staudt, K. Rethinking Em(power)ment Gender and Development: An Introduction. In Rethinking Empowerment: Gender and Development in a Global/Local World; Parpart, J.L., Rai, S.M., Staudt, K., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0415277693. [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adelman, S. The Sustainable Development Goals, Anthropocentrism, and Neoliberalism. In Sustainable Development Goals: Law, Theory and Implementation; French, D., Kotzé, L.J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 15–40. ISBN 978-1-78643-875-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H. Anthropocentrism: Problem of Human-Centered Ethics in Sustainable Development Goals. In Life on Land. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Filho, W.L., Azul, A.M., Brandil, L., Salvia, A.L., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Skolverket. Handledarguide Hållbar Utveckling. Available online: https://larportalen.skolverket.se/LarportalenAPI/api-v2/document/path/larportalen/material/inriktningar/01-hallbar-utveckling/Gymnasieskola/902-Hallbar-utveckling-GY/se-aven/Material/A1_Gy_Handledarguide.docx (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Colding, J.; Barthel, S.; Bendt, P.; Snep, R.; van der Knaap, W.; Ernstson, H. Urban Green Commons: Insights on Urban Common Property Systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondents (Age, Gender) | Organization | Title/Main Work |

|---|---|---|

| #1 (40–50, F) | A: municipal public sector | Unit manager working with social sustainability |

| #2 (30–40, M) | A: municipal public sector | Related to social sustainability towards the citizen |

| #3 (40–50, F) | B: municipal public sector | Assisting schools in developing environmental strategies |

| #4 (40–50, F) | B: municipal public sector | Project leader for Education for Sustainable Development towards schools |

| #5 (60–70, F) | B: municipal public sector | Operational manager within education and school systems |

| #6 (20–30, F) | C: public sector, municipally owned company | Coordinator for “social wellbeing” towards tenants |

| #7 (60–70, M) | D: non-profit association/civil society | Manager at youth center |

| #8 (30–40, M) | D: non-profit association/civil society | Youth center leader, working with youth aged 13–19 |

| #9 (40–50, F) | D: non-profit association/civil society | Youth center leader, working with youth aged 13–19 |

| #10 (40–50, M) | E: municipal public sector | Deputy unit manager for field social workers |

| #11 (30–40, F) | E: municipal public sector | Field social worker towards youth (initially targeted at ages 13–19 but later expanded to those who are younger and older) |

| #12 (40–50, F) | F: municipal public sector | Unit manager at support and prevention unit |

| #13 (30–40, F) | F: municipal public sector | Family therapist, working mainly with children and youth aged 6–20 |

| #14 (60–70, F) | F: municipal public sector | Family therapist, working mainly with children and youth aged 6–20 |

| #15 (40–50, F) | G: municipal public sector, municipal association/local authorities | Strategist for work for sustainability |

| #16 (50–60, F) | G: municipal public sector, municipal association/local authorities | Coaching, providing education, and leading projects related to an environmental perspective |

| #17 (30–40, M) | H: Non-profit association/civil society | Manager at youth center, working with youth aged 13–19 |

| #18 (30–40, M) | H: Non-profit association/civil society | Deputy manager at a youth recreation center, working with youth aged 13–19 |

| #19 (30–40, M) | I: municipal public sector | Working with crime-prevention programs and education, especially with non-profit associations and schools |

| #20 (50–60, M) | J: municipal public sector | High school deputy principal |

| Themes | Codes Related to Themes |

|---|---|

| Knowledge/awareness | Respondents’ knowledge/awareness of SD and the SDGs Respondents’ knowledge/awareness of ecosocial relationships Power position |

| Youth empowerment | Youth participation Youth involvement Power position |

| Available and needed circumstances for SD work and ecosocial discourse with youth | Youth participation Youth involvement Power position Collaboration Network |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, E.; Sjöberg, S.; Turunen, P.; Rambaree, K. Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: Exploring Ecosocial Work Discourses. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063426

Chang E, Sjöberg S, Turunen P, Rambaree K. Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: Exploring Ecosocial Work Discourses. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063426

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Elvi, Stefan Sjöberg, Päivi Turunen, and Komalsingh Rambaree. 2022. "Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: Exploring Ecosocial Work Discourses" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063426

APA StyleChang, E., Sjöberg, S., Turunen, P., & Rambaree, K. (2022). Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development: Exploring Ecosocial Work Discourses. Sustainability, 14(6), 3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063426