Abstract

Accessible design within the built environment has often focused on mobility conditions and has recently widened to include mental health. Additionally, as one in seven are neurodivergent (including conditions such as ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and dyspraxia), this highlights a growing need for designing for ‘non-visible’ conditions in addition to mobility. Emphasised by the growing disability pay gap and the disability perception gap, people with disabilities are still facing discrimination and physical barriers within the workplace. This research aimed to identify key ways of reducing physical barriers faced by people with a disability and thus encourage more comfortable and productive use of workspaces for all. Once the need for designing for a spectrum of users and inclusive workspace design was understood, a survey was then circulated to students and staff at a large university in the UK (working remotely from home), with the aim of understanding how people have adapted their home spaces and what barriers they continue to face. Quantitative and qualitative results were compared to the literature read with key issues emerging, such as separating work and rest from spaces in bedrooms. The survey findings and literature were evaluated, extracting key performance-based goals (e.g., productivity and focus within a study space) and prescriptive design features (e.g., lighting, furniture, and thermal comfort), whilst also considering the inclusivity of these features. The key conclusion establishes that, to achieve maximum benefit, it is important to work with the users to understand specific needs and identify creative and inclusive solutions.

1. Introduction

To ensure the built environment contributes to an equal and inclusive society, we need to ensure our spaces are being designed to be accessible and inclusive. Until recently, the discussion regarding equality in the use of the built environment focused on physical access [1,2] as this has improved, the discussion has only just widened to address mental health and neurological conditions [3,4,5].

‘If you do not intentionally, deliberately and proactively include, you will unintentionally exclude’.Jean-Baptiste [6].

Including understanding the user, it should be noted that there is a strong relationship between inclusive design and sustainability [7,8]. As mentioned, successful integration of inclusive design within the design process contributes to the overall usability of the space, thus improving the overall sustainability of infrastructure [1]. Similarly, by following the social model of disability, designers must aim to remove barriers experienced by the user, hence shifting the responsibility onto the designer to actively design a better space. This responsibility shift is similarly seen in designing purely for environmental sustainability: for example, designers actively implementing on-site renewables to reach net-zero. This appears to be a ‘big-picture’ approach, vital to including and integrating sustainability and inclusive design into the overall process.

While sustainability can be quantified in physical terms, and therefore tools developed to support sustainable design, performance assessment of inclusive design requires the involvement of the user [9,10,11]. Thus, the user should have a more prominent part in specifying inclusive design features, and hence a more effective balance between the opinions held by the designer and user would appear more effective. This is evident in recent studies regarding the design of healthcare facilities [12], where user centeredness is highlighted as one of the most important concepts to pursue, which was raised through quantitative and qualitative results.

Disability Rights UK recommends that employers need to create cultures in which people living with conditions feel more confident, and they should embed flexible working practices and thorough mental health services within companies [13]. By creating more comfortable and flexible work environments, we are, in turn, designing for the future, to create socially and physically sustainable spaces, contributing to long-term usability and economic viability [1] but also making the best use of the workforce.

This paper aims to add to this discussion, by analysing existing research on the design of workspaces from an inclusive design perspective, focusing on non-mobility conditions.

2. Background

Workspace adaptations for people with disabilities have often focused on physical adjustments for people with mobility-related conditions, such as implementing ramps and lifts. A key issue highlighted in research regarding the implementation of workspace adaptations is the dependence on goodwill and a dedicated senior leadership team [14,15]. This implies stricter inclusive regulations to improve the overall baseline.

Within the last year, research has been published specifically identifying workplace adjustments for people with autism [16,17]. While studying autism is a large step in designing inclusively, we must also consider a spectrum of conditions aligned to the term neurodivergence. Overall, improving the baseline in regulations and policy, by considering neurodivergence, can help to improve inclusive design.

2.1. Inclusive Design Applied in the Built Environment

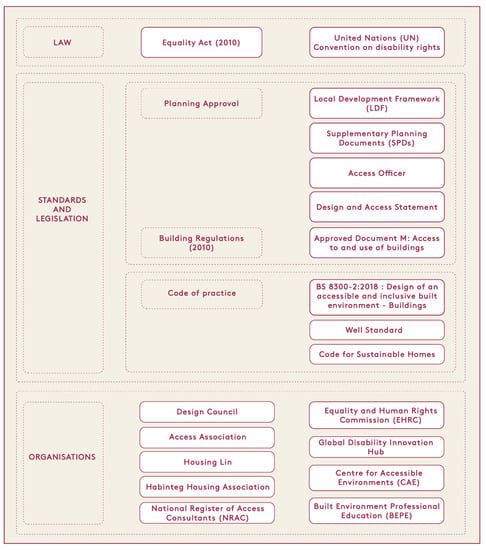

The Equality Act imposes duties to make reasonable adjustments and provide equality of service; however, it does not say how the built environment should be altered. This is provided through the Building Regulations and the Approved Documents; approval of these regulations is mandatory for all new buildings, extensions, and material changes. Figure 1 below shows a breakdown of key laws, standards, and organisations that further feed into integrating inclusive design into the built environment within the UK.

Figure 1.

Overview of influential inclusive design organisations, guidance, and legislation.

Access and inclusive design professionals most commonly refer to Approved Document M: Access to and use of buildings (ADM), often also referring to BS 8300-2:2018 that provides additional guidance.

These guides are useful in providing the minimum criteria for the design of buildings and are largely developed via lived experience, e.g., the Grenfell Tower disaster and fire safety [18]. These building regulations have been described as the ‘least acceptable solution’ [19] and seem to largely hold issues at their creation; as Imrie states:

‘The regulation is based on a medical conception of disability that assumes that the primary problem for disabled people, in gaining access to dwellings, resides with their impairment’.—Imrie [20]

This describes a sense of blame on the person with the disability, an idea that Imrie goes on to highlight as a widespread view amongst the industry.

It should be noted that designing for wellbeing is not prominent in the Approved Documents; terms such as ‘well-being’ and ‘mental health’ were searched for throughout ADM, finding no occurrences. Furthermore, terms used to represent some non-visible disabilities, including ‘autism’ and ‘dyslexia’, also had no occurrences. This highlights a clear lack of mandatory guidance surrounding non-visible conditions.

2.2. Disability and the Workspace

The need for accessible workspace design can be justified by considering demographics, and thus the users to design for and with. The Family Resources Survey (FRS) reported that in 2019/20, 22% of people in the UK reported a disability, roughly equivalent to one in five [21]. Mental health conditions rose from 25% to 29% of the total reported cases, equating to approximately one in fifteen of the population. Designing without proactively considering the broad range of disabilities is therefore not acceptable.

Furthermore, the breakdown per age group shown in Figure 2 highlights the distribution of ‘visible and non-visible’ disabilities, i.e., mobility and mental health conditions, respectively. It concludes that for working-age adults (16–64), 42% reported a mental health condition, further emphasising the need to provide inclusive workspaces. The age groups also do not add up to 100%, implying respondents reported more than one condition, reinforcing the need for intersectional and broad inclusive design.

Figure 2.

Family Resources Survey, 2020, showing percentage of people with a disability per age group and condition [21].

When considering workspaces, we should consider neurodiversity. This term refers to the different ways our brains work and interpret information; most people are neurotypical, which means their brain functions in the way society expects it to. About one in seven people are neurodivergent [22], meaning that their brain functions, learns, and processes information differently; this includes attention deficit disorders (ADD or ADHD), autism, dyslexia, and dyspraxia. It should be noted that most forms of neurodivergence are experienced along a spectrum; the associated characteristics vary from person to person and can change over time [22]. Considering the limited research on the way in which neurodivergent people operate in workspaces designed for neurotypical people, it is essential to explore this further.

Additional to the physical environment, social attitudes regarding disability must be considered to improve workspaces. The disability equality charity Scope published a report in 2018 [23] highlighting the disability perception gap, which shows the public continuing to stereotype and negatively view people with disabilities; it reported that one in three people see disabled people as being less productive than non-disabled people [23]. Scope states that workplaces must tackle attitudes and misconceptions to encourage more disabled people in work.

One way Scope proposes to tackle these attitudes is using the social model of disability, which is part of their ‘Everyday Equality Strategy’, aiming to change attitudes towards disabled people. Scope describes it as follows:

‘The model says that people are disabled by barriers in society, not by their impairment or difference. Barriers can be physical, like buildings not having accessible toilets… removing these barriers creates equality and offers disabled people more independence, choice and control’.—Scope [23]

This highlights the importance of removing barriers within daily life and thus reflects the mentality that designers should embody when designing. Thus, a key principle of design is to create spaces where such barriers are removed; this is how designers think of ergonomic features or systems that aid the occupants (lifts, lighting, acoustics, etc.). Therefore, while the principles of design are not being changed, most of these features need to be reconsidered in a more inclusive way.

2.3. Workspace Design Considerations

To identify the inclusivity of current workspace design, a consideration must first be made regarding current trends in workplace and library design, identifying the overlaps between obtaining optimum productivity and happiness, with a focus on inclusivity.

The design of workplaces aims to improve work performance both in quantity and quality [24]. Open-plan working [25] and hot-desking have shown negative and non-inclusive impacts: less pleasant co-operation and increased uncertainty and mistrust [26,27,28,29].

Promisingly, serious considerations of different student learning styles have begun to influence the interior design of libraries [30], creating comfortable, quiet, and safe environments for self-regulated learning activities [31]. This is representative of the recent considerations of designing quiet spaces in building design, which aim to tackle stress and sensory overload. Sadia’s study exploring the design preferences of neurodivergent populations for quiet spaces [17] found that there are contradictory user needs; this aligns with the College of Estate Management (2010):

‘For example, dropped kerbs, essential for wheelchair users, can confuse visually impaired people unless tactile surfaces or audio signals are incorporated’.—CEM [1]

Sadia’s report is driven by the mentality of designing with a specific end user (people with autism), whereas the CEM speaks to the broader picture (with examples such as the one above).

When considering the goal of inclusion and effective work performance, individuality must be noted; every person works and studies at different speeds. Understanding how we work could reinforce inclusion in the workspace: for example, understanding the human need for concentration and the physical and mental conditions required for knowledge management and absorption [32,33,34,35]. An important physical takeaway from this research is the importance of ‘zoning’ and its relevance to individual workspace and play [36].

One way of developing our understanding of people and space is through working with people with a disability. For example, a phenomenological inquiry into how people with a visual impairment use their space highlighted key details that may not have been reached by someone without this condition [37]. Familiarity of a space is also a need for many people with dementia [38], hence the transferability of inclusive design. It is important to understand and recognise that achieving optimum inclusion and work performance is achieved through individuality and adaptability.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many bedrooms and living rooms have been adapted to be home offices and study spaces. From a business perspective, home-based ‘teleworking’ (remote working using technology) has become an urgent solution with minimal cost [39]. Many offices and universities are beginning to propose flexibility [40,41] in work environments; over 87% of people stated their desire to work from home for at least part of the working week [42]. Furthermore, from a spatial design perspective, the post-pandemic office and home space may adapt, with the increased demand for more garden spaces and internal partitions [43].

Looking forward at the ways in which inclusive design and accessibility are changing in the digital world provides an interesting exploration into the mentality of the design process. This will update the design process to actively promote inclusive design and reframe how disabilities are displayed.

2.4. Designing for a Spectrum of Needs

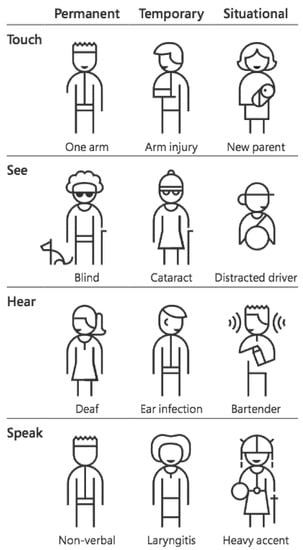

The concept of the ‘persona spectrum’ is commonly used in digital design and could lead to a positive impact that aligns with the design of physical spaces. In summary, the persona spectrum is a mentality and method of considering a range of users to inform solutions. Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Toolkit [44] reinforces the idea that ‘points of exclusion’ (i.e., where users may find difficulty in using a product) help designers to generate new ideas and design inclusively, mentioning that:

‘Designing with constraints in mind is simply designing well’.Shum et al. [44].

This focuses on mapping human abilities on a spectrum to inform solutions that inevitably benefit everyone, as shown in Figure 3 [44].

Figure 3.

Persona spectrum—Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Toolkit [44].

This focus on studying user interaction is replicated in community consultations that take place in the design of physical spaces [45,46]. The aspect that seems to demand improvement in consultations is this understanding that studying the strategies and solutions developed by people with disabilities can stimulate the design process and is vital in promoting innovative and effective spaces [1]; conclusively, what we design is a result of how we design [44].

3. Methodology

3.1. Overview and Goals

The aim of this study is to better understand our demands of our work/study spaces, and how we can independently adapt them. Given the prolonged period people are spending within their remote working spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic, this provides an abundance of information regarding how we independently adapt our spaces. This method is similar to a study carried out in 2018 titled ‘How do you work? Understanding user needs for responsive study space design’ [47]. The researchers sent out a survey with a mix of open-ended and multiple choice questions, to aid the design of a library. However, the analysis was largely quantitative, reaching the conclusion that their library could be anywhere, although this was contradictory to the greater separation/zoning effect presented by a library.

In this study, a mix of qualitative and quantitative survey questions was sent to various members of staff and students at a large university in the UK, to allow for further understanding of attitudes and drivers. From this, a sequence of coding was carried out, i.e., the process in which words and/or themes are taken from the qualitative data and used as ‘codes’ or labels to categorise and organise data, using Microsoft Excel and Word. Themes and quotes were extracted, which were then analysed and compared with the literature. Conclusions were then presented as prescriptive and performance design factors, to aid the design of inclusive workspaces.

3.2. Method of Data Collection

3.2.1. Survey Overview

The full survey, created in Google Forms, can be seen in Appendix A, and the survey received institutional ethics approval. A summary of the survey can be seen below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Survey overview.

As mentioned in the overview, the main goal was to increase the understanding of users. A mixed methods approach was taken, with both quantitative and qualitative results. This is due to the likelihood that many parts of the results will contradict themselves [48], and thus having the original thoughts and text aids the quantitative results.

Two samples were collected; both consist of people either working or studying mostly remotely (as opposed to on campus) as per UK government guidelines.

Sample A consisted of 60 students and staff within the same department (approximately 88% student). Although the abundance of data may risk generalising experiences, by limiting the attention each respondent receives [49], this can be mitigated through extracting key quotes and optimising the analysis time [50,51]. The nonhomogeneous nature of staff and students grouped together should provide overarching design considerations within the two remote settings; they also represent the ‘working-age adult’ as identified in the FRS survey described above. Discrepancies may occur from the differences between ‘working’ and ‘studying’, potentially related to work schedules and resources; however, they will be assumed to be minimal for this study. Sample A’s relevance to the main goal applies to understanding users and their work/study setting; this sample provides a representation of the general population.

Sample B consisted of 15 members of staff at UCL, who are part of the Neurodivergent Staff Network (the members of the network identify as autistic or dyslexic or have Tourette syndrome or ADHD) and Enable@UCL (a staff network open to any disabled person working at UCL as well as non-disabled persons with an interest in promoting disability equality at UCL). Choosing a variety of networks allows a larger scope for identifying conflicts between disabilities and user needs; there is also a noticeable gap surrounding research of neurodivergence and the built environment. Due to data protection and the lack of student-run neurodivergent groups, students were not included in this sample. Sample B is representative of experts, with personal experience within this gap.

The survey was circulated via the course administrator and the individual network contacts listed on the university page. The survey was sent via email once and closed after three weeks, to reduce the risk of fatigue and prevent duplicates (although these were removed in the first stage before assembling results). All responses were submitted through Google Forms anonymously by each respondent.

3.2.2. Method Strengths

The mixed methods approach should prove effective at ensuring answers are thorough and relevant to the question; the quantitative results (e.g., lighting impacting wellbeing the most) will be compared to the qualitative results (e.g., how certain levels of lighting keep the respondent feeling awake and alert), allowing more succinct user understanding. Similarly, the method of cross-evaluating these responses with the literature should highlight key factors going forward into the design of workspaces and understanding how we work. The questions focus more on attitudes as opposed to physical design features as these are largely covered within the literature. Although this makes it more difficult to find alignment in the abundance of literature surrounding these features, it explores a relatively new angle to the overall design of workspaces (focusing on performance as opposed to prescriptive goals).

The two samples also have a diverse set of expected activities: ranging from working to studying to creative tasks. Although this increases complexity and potentially decreases consistency in the research, it provides a more realistic outlook on workspaces, and the reality of expecting changing tasks and demands [52], which has been exacerbated by working remotely [53]. This additional information provided by recognising the value in individual responses is new, due to the limited exposure to this level and intensity of remote working.

3.2.3. Survey Questions

As mentioned, the full list of survey questions can be seen in Appendix A; a summarised version is presented in Table 1 above. The survey questions were aligned to the goals of the methodology.

When creating the survey, it was also important to consider survey response fatigue, a sense of overwhelm due to a growing demand for responses, and survey taking fatigue, which occurs during the survey and is a result of very long surveys with little application from the respondent [54,55,56]. To avoid this, shorter survey questions and mixed methods are suggested to reduce the open-ended questions and ensure the survey is doable in five minutes. From an inclusive design perspective, it is also important to be mindful about the questions being asked and the language used and provide reasons regarding demographic questions [57].

Appendix A Table A1 shows a breakdown of the questions regarding the overall theme (with a brief reasoning), question details, and question type. As the table shows, there are more multiple choice questions (to avoid fatigue) and they are also used to break up the open-ended questions. Multiple choice questions are also used to ease the respondent into the survey to understand the overall scope without unconsciously impacting their response; later in the survey, specific spatial features such as acoustics, furniture, and thermal comfort are used to generate more ideas and space evaluation. The specific questions were inspired by the survey carried out by Hedge et al., in their 2018 study of learning spaces [47], asking participants about the best and worst elements of their spaces, what inspires and leads them to use these spaces, and the attributes that would improve their experiences. Similarly, the demographic questions were placed at the end as this is in line with the social model of disability; this information is additional to the main understanding of their space as opposed to being the focus.

3.3. Method of Analysis

As a mixed methods approach, two overarching methods of analysis were used, one for the quantitative questions and one for the qualitative questions. The quantitative analysis method encompasses the multiple choice and checkbox questions, and the qualitative analysis method focuses on the open-ended questions. Microsoft Excel and Word were used for the analysis, due to their capabilities in visualising, rearranging, and commenting on the data.

The quantitative analysis method largely focuses on demographics and identifying extremities regarding user preference, e.g., their age and highlighting what aspects of their space contributes the most to their wellbeing. This method quantifies the responses, to show whether there is correlation in what features respondents want most in their spaces or the overall adaptability of their space; these are then graphically presented to see trends (see Section 6, Results).

The qualitative method focuses on the open-ended questions; using ‘coding’, also known as labelling the data, to identify key repeated themes [48]. Through labelling the data, key mutual themes are identified that describe relationships between the survey responses. There are multiple ways to do this: either quantifying repeated words across all responses, or intuitively reading and extracting themes [48].

The first cycle of coding (i.e., the researcher’s first level of reading and analysing the data) was to typically quantify the repetition of themes or words, although this may have been more time-efficient for the larger sample; this risks limiting users to numbers as opposed to specific experiences and thoughts. Thus, it was more beneficial, especially for sample B, to keep the original content and search for alignment in addition to quantification; this was carried out by counting and providing corresponding examples. This is known as ‘in vivo coding’, using the participant’s own language as the code [48]. The second cycle of coding aimed to identify key conclusions and more critical evaluation, by reconsidering new themes and alignment from the quantitative results. This was conducted by comparing codes from the first cycle and condensing into smaller units such as themes and concepts, focusing on questioning the results of the first cycle to aid explanations or patterns. The data were also compared to the literature to identify whether there is clear alignment with previous research and reinforce conclusions.

Furthermore, there will be significant overlaps and contradictions between data due to the overlapping themes mentioned in the survey [58], hence the importance of the mixed methods approach and considering the responses from both quantitative and qualitative analyses [59]. The qualitative data are presented as explanations or patterns, whereas the quantitative data are visually represented through graphs and figures; ultimately, when analysis takes place and the methods are integrated, one takes slight priority over the other (likely qualitative data for a more user-focused approach) [60]. The mixing of the approaches occurs in the study design stage at the start, and during the interpretation of the outcomes of the entire study during the discussion [60].

4. Results

The results present the demographics first, to further highlight the context of the samples, before further design-related questions. The response rate for sample A was 30%, and for sample B, it was approximately 15%. Furthermore, the chart formatting has additional labels and outlines, and different levels of bar darkness in the charts, with clear section themes, for improved clarity. Discrepancies in total percentages are due to a ±1% rounding error.

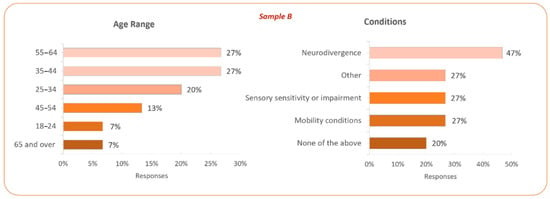

4.1. Demographics

Firstly, a few details regarding the demographics for each of the samples are presented (Figure 4 and Figure 5); these reconfirm the original participant information and sample descriptions. Sample A was predominately 18–24 (88%) with fewer conditions (82%), whereas sample B was more varied across age, with a majority of neurodivergent respondents. As sample A consisted of mostly 18–24-year-olds, based on the circulation of the sample, they were assumed to be students in family homes (as many universities have switched to remote learning) [61]; hence, 88% of the sample should be assumed to be students.

Figure 4.

Demographics (sample A).

Figure 5.

Demographics (sample B).

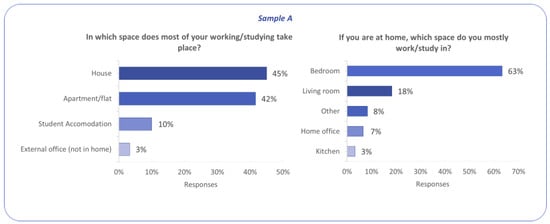

4.2. Spatial Context and Overall Use

The survey then interrogated where the participant worked and if they worked at home; they were then asked where in the home they worked. As shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7, most respondents in sample A worked in a bedroom at home, whereas in sample B, there was more diversity in where they would work; this is representative of the sample type and circulation. The quantitative data are missing information regarding overall room availability; however, participant responses to ‘why have you chosen this area?’ (Table 2 and Table 3) should highlight personal availability. These responses were split into a variety of themes (‘codes’ as described in Section 5), the most common being ‘convenience’ amongst sample A, and the ‘location of furniture’ for sample B. This begins to answer the questions of availability raised earlier, and raises questions regarding design drivers within workspaces, i.e., quiet space, natural light, and views. Furthermore, comparing the left and right graphs shows that regardless of available space (i.e., multiple rooms in a house), most participants in sample A work/study in their room, representative of the assumed 88% student response. Overall, the location is less the focus of this study than understanding how the space, even if limited, is used.

Figure 6.

Location of work/study amongst respondents (sample A).

Figure 7.

Location of work/study amongst respondents (sample B).

Table 2.

Why have you chosen this space? (Sample A).

Table 3.

Why have you chosen this space? (Sample B).

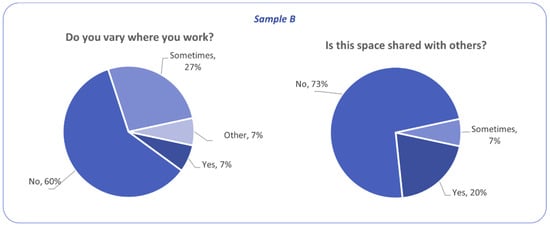

Most of the participants did not vary where they work (Figure 8 and Figure 9), i.e., they remained in the same space for most of the day; again, this may link to limited availability. In the ‘other’ category, a respondent mentioned occasionally working in the library if available. Most also did not share this space with anyone, highlighting a desire for privacy and solitude.

Figure 8.

Further context regarding overall space (sample A).

Figure 9.

Further context regarding overall space (sample B).

4.3. Spatial Changes and Individual Use

Once easing the participant into contemplating their workspace, further questions were asked regarding their overall use. The respondents were asked whether any changes had been made over the past year (Figure 10); this identifies specific categories that hold barriers to the use of their space. By asking this, we also begin to learn the priorities of the user, identifying what they can physically change by themselves and what matters the most to them to change. A total of 60% of respondents from sample A selected furniture, with 87% from sample B.

Figure 10.

Recent changes made by respondents.

In light of the previous question, respondents were then asked why they carried out these changes (Table 4 and Table 5). The most common driver from sample A was mood, with the aim of becoming ‘more motivated and concentrated to study’ and improving their overall work efficiency. For sample B, furniture, room decoration, and mood acted as larger factors in why they carried out changes. From this and the previous results, we begin to understand the user’s beliefs in what generates a positive work environment, and how they have created this for themselves.

Table 4.

Regarding the previous question, why did you carry out these changes? (Sample A).

Table 5.

Regarding the previous question, why did you carry out these changes? (Sample B).

The respondents were also asked whether any barriers continue to exist within their space (Table 6 and Table 7). This question reiterates the social model of disability but also blatantly requests areas of improvement from the participant. The most common response for sample A was the separation aspect: ‘can’t seem to relax as my home is also where I work’. Sample B reiterated the previous answer with a focus on furniture.

Table 6.

Similarly, are there any specific barriers you continue to experience in your space? (Sample A).

Table 7.

Similarly, are there any specific barriers you continue to experience in your space? (Sample B).

4.4. Wellbeing

The respondents were also asked about wellbeing within their space (Figure 11 and Figure 12). Again, this aims to identify key personal drivers in improving wellbeing within workspaces. Lighting appeared to be the most influential within sample A’s space; however, for sample B, furniture prevailed, and lighting was one of the least influential. This contradiction refers to the previous raised question of priority; many of the qualitative responses from sample B focused on ergonomic work conditions as opposed to daylight. Members of sample B were also asked which contributes the least, where room decoration was the most common. The data lack a comparison of both samples regarding the barriers to positive wellbeing due to the question only being offered to sample B. In ‘other’, both samples made references to having a ‘fixed place to work’ and having family around.

Figure 11.

Most impact on wellbeing (sample A).

Figure 12.

Most and least impact on wellbeing (sample B).

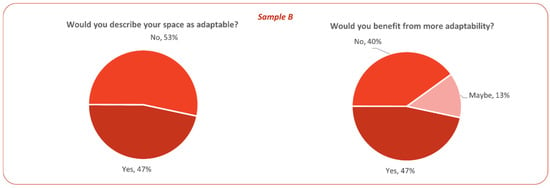

4.5. Flexibility/Adaptability

Respondents were then asked about the adaptability and flexibility of their spaces (Figure 13 and Figure 14). This was varied across all results; largely, both samples did not describe their space as adaptable; however, sample A appeared to be more in favour of more adaptability than sample B. This is contradictory, and Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 aim to further analyse this. The next question asked the respondent to expand on this, asking why they thought their space was flexible/inflexible (Table 8, Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11). This was largely related to the furniture within this space, and the moveability amongst a fixed room size: ‘limited configurations’, using furniture to ‘compartmentalise’, ‘restrictive space for moving furniture’. Although these results do not reaffirm the previous question, they begin to highlight innovative spatial considerations that improve flexibility (such as furniture with wheels) as well as further determining barriers in achieving adaptability (such as room size or furniture weight).

Figure 13.

Adaptability within their space (sample A).

Figure 14.

Adaptability within their space (sample B).

Table 8.

If yes, what makes it flexible/adaptable? (Sample A).

Table 9.

If no, what makes it inflexible/unadaptable? (Sample A).

Table 10.

If yes, what makes it flexible/adaptable? (Sample B).

Table 11.

If no, what makes it inflexible/unadaptable? (Sample B).

4.6. Control

A limitation of the previous questions regarding adaptability is the assumption regarding personal control over space. The respondents were then asked about the levels of control they had within their space (Figure 15). There appeared to be a consensus from both samples, identifying lots of control over their spaces, hence confirming the assumption.

Figure 15.

Levels of control.

4.7. Miscellaneous

The last few overarching questions focus on what works well and overall comments (Table 12, Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15). Furniture was the most common answer from both samples: ‘height adjustable chair’, ‘nice setup easy to connect to my laptop’, ‘dedicated space for certain tasks’. At this point in the survey, we notice more repetition in responses; although this is beneficial in strengthening key design drivers, it may also be a sign of fatigue from respondents.

Table 12.

What works well in your work/study space and why? (Sample A).

Table 13.

What works well in your work/study space and why? (Sample B).

Table 14.

Any other comments about your space? (Sample A).

Table 15.

Any other comments about your space? (Sample B).

5. Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Interior Design

5.1.1. Furniture

The relevance of furniture within inclusive design lies heavily in the study of ergonomics, i.e., the interaction of people and elements of a system [62]. For example, a good ergonomic chair would have an adjustable seat and armrest that aids comfort and promotes wellbeing [63,64,65]. These features are important when considering the intersection of disabilities and designing for adaptability (adjustability and independence).

The responses from sample B heavily align with the literature findings; the most frequent responses regarding recent changes were related to furniture and specifically the repetition of ergonomic chairs and desks. This confirms Helander’s studies describing the aid in comfort and wellbeing provided by adjustable seats and armrests [63]. Furthermore, furniture appears to work the best in most respondents’ work/study spaces, with many creative solutions such as ‘curtains to reduce distraction and lift up for relaxation’ and ‘two tables between which I move around’.

Having an additional desk for a different purpose suggests a positive solution to hot-desking, rather than creating limitless options, perhaps allowing employees the option of switching occasionally. A respondent in sample B mentioned, ‘I also have another desk area for creative work so I can split my brain! It is hard to break tasks down as a dyslexic so dedicated space for certain tasks is key for me.’ In terms of neurodiversity, research shows higher levels of creativity amongst neurodivergent individuals; creating this separation along with dedicated quiet and private spaces encourages and supports more comfortable working environments [66,67].

As the students in sample A appear to work on a variety of different activities that require a lot of material and space, the repetition of desk size is prominent.

Furniture contributed the most to the self-reported wellbeing of sample B. It does appear that although many positive responses were reported for the furniture within their spaces, it was one of the most common barriers experienced, regarding the comments ‘limited desk space’, ‘desk height isn’t ideal’, and ‘not enough space for me to be organised as I would want to be’.

5.1.2. Room Decoration

Calming images and artwork can influence wellbeing. A study in 2003 of chemotherapy patients who were exposed to rotating art exhibitions showed reductions of 20% in anxiety levels and 34% in depression [68]. It should be noted that people could experience sensory overload depending on the colours and contrast used in the artwork [69]; hence, involving users in these decisions is vital.

Overall, how their rooms were decorated contributed the least to both samples’ wellbeing within their spaces (13% for sample A, and 7% for sample B, with 47% of sample B also stating it contributes the least). Additionally, most of the responses directly related to room decoration were from sample B. One respondent mentioned how they ‘painted walls for a change in scenery and to brighten room up’; although a creative solution to this sense of ‘captivity’, it could be a temporary solution requiring additional planning and mobility.

However, there are a few mentions of plants, largely from sample B: ‘the plant allows me to feel a sense of freshness’, ‘being able to see houseplants while I’m working makes me happy’, ‘having art and plants nearby which brings me moments of joy and inspiration’. Overall, the impact of plants does appear positive, aligning with biophilic research [5,70,71]; however, the lack of specific questions regarding this may have potentially prevented the respondents from delving into this ‘joy and inspiration’. Sadia’s study of quiet spaces as mentioned earlier also shows preferences for nature-orientated quiet spaces for people with autism [17], reiterating the calming impact of biophilic design.

Nevertheless, compared to the ergonomics of their furniture, the decoration of their room did not appear to influence their overall positivity as much, although it did appear most acknowledgeable by sample B (potentially relating to the higher levels of creativity mentioned above).

5.1.3. Layout

As mentioned earlier, the familiarity of a space is vital for certain user needs. People with dementia are known to benefit from a sense of familiarity [72,73]. This is similar for those without dementia—a familiar environment filled with physical memories ‘promotes a sense of coherence… supporting the continuation of self’ (73). This importance of familiarity with physical memories (such as photos and memorabilia) reiterates the earlier mentions of the value of personalisation in a space.

There were frequent mentions across both samples of the lack of separation from work and rest; this confirms the influence of ‘zoning’ and its importance in achieving concentration and knowledge absorption [31,32]. It was the most frequent response to barriers experienced within the respondents’ workspaces, regarding the lack of ‘distinction between work and relaxation’ or the difficulty in ‘motivating yourself to do work in the same space you sleep’, and this creating ‘a negative effect on my mental health’.

There appeared to be a few creative solutions such as the curtain idea, in the sense of optimising all corners of a space to create a different environment: ‘my height adjustable chair makes things feel different’, ‘the room is divided up into different sections through furniture allowing one part to be adapted easily into a workspace whilst retaining its original purpose as well’. This use of furniture to stimulate different environments is conflicting as this could impact wayfinding, preventing clear routes through spaces and creating trip hazards which could increase stress when travelling around. Colours or signage could be used to encourage separation [74]. However, creating this semi-open boundary provides safety and increases concentration [75]; this separation barrier demands creative solutions due to its shared response across both samples.

5.2. Environmental Design

5.2.1. Lighting

Lighting contributed the most to the wellbeing of sample A. It was also one of the most common drivers across both samples for choosing a space: ‘good natural lighting’, ‘natural light and no distractions’, ‘control over lighting’.

Replicating the typical daylight rhythms proves to be most effective in creating productive environments by regulating the circadian rhythm [76]. The survey reported lots of conflicting comments regarding daylight: ‘there are also issues with the light from the window in my room at certain times of the [day]’, ‘less lighting in general than on campus spaces which makes it harder for me to work in the evenings’. The second comment is interesting because although it is good to prevent long work hours due to the impact on wellbeing [75,77], it suggests their ‘flow’ period is much later in the day. However, potentially more detail regarding work/study schedules would be required to align daylighting and ‘flow’ periods.

Many mentioned conflicting opinions regarding workspace placement in relation to windows: ‘glare into my eyes because it’s next to the window’, ‘direct sun in eyes in the mornings’. One respondent suggested a holistic solution to glare by using a ‘dark wall colour [to cut] down on glare in the space’; this could also provide a clear visual contrast between lighter furniture/flooring, supporting clearer wayfinding.

Lighting was also used to increase motivation and prevent tiredness: ‘daylight really increases motivation at times’, and one respondent mentioned changing their lighting ‘because it used to make me sleepy’, and ‘daylight is very important to feel fresh and ready to work’. However, a conflicting comment, ‘not too much sunlight [as] it’s very bothering especially when spending all this time in it’, refers back to the external lack of control and prolonged exposure. Furthermore, this comment does contradict the literature that states the positive impacts on wellbeing from bright light [78,79], highlighting the individuality of workspace design, and lack of inclusion considerations in previous research.

Control over lighting was extremely important. Many respondents enjoyed having ‘control over lighting’ using ‘lamps... put in different places on purpose’: ‘lamps were installed to make it usable after dark’, aligning with the literature stating improvements in productivity from control over lighting [80,81]. Furthermore, one respondent mentioned ‘the lights at night are warm coloured creating a beautiful atmosphere’.

Overall, lighting preferences and needs were related to individual factors, as opposed to the separate samples (i.e., daylight, workspace placement, motivation, and control).

5.2.2. Thermal Comfort

The largest influence on thermal comfort across both samples was the increased levels of control; when asked what works well within their workspace, one respondent replied, ‘I can control the temperature’, similar to another stating, ‘I can control the heating so that it doesn’t get too cold or warm which is useful as it keeps me awake and alert’. This confirms Grigoriou’s suggestions that control produces positive impacts on productivity; however, this may only work well in an individual setting. Within a larger workplace, shared with others, this could cause conflict [76,81]. Furthermore, a study carried out in 2013 showed that the majority of women working through menopausal symptoms found hot flushes particularly difficult, which impacted their work performance, as well as feeling a sense of discomfort when disclosing this to managers [82]. This provides evidence for improving independence and control within the workplace, whilst also improving perceptions of conditions.

Furthermore, across both samples, thermal comfort proved a large contributor to wellbeing: ‘once the heating is up it is a pleasant space to inhabit’. Overall, both samples appeared homogenous in the impact of thermal comfort.

5.2.3. Acoustics

Quietness was prevalent through two respondents in sample B purchasing noise-cancelling headphones, with one mentioning ‘to block out noisy neighbours either side’. However, like thermal comfort and lighting, one respondent mentioned, ‘I have the room to myself so I can control the noise levels’; this suggests limited background noise and reiterates the demands of ‘solitude’. Although silence appears to prevail regarding acoustic design, recent research into the idea of ‘sound masking’ poses a second option to ‘mask’ the typical murmur of HVAC systems with calming sounds to also increase sound privacy [83]. This is confirmed by a study into the restorative quality of nature, by highlighting the improved wellbeing of enjoying biophonic sounds [84]. However, this can be distracting and confusing for people with a visual impairment or who rely on their hearing for wayfinding.

A respondent (from sample A) mentioned a barrier that ‘sound clashes if me and my roommate are both in calls’, similar to respondents (across samples A and B) mentioning family members at home. This is similarly representative of the ‘open-plan’ office and could contribute to sensory overload. The idea of the semi-open cubicle to provide physical boundaries could be a feature integrated with additional acoustic panels, preventing sound clashing [85,86]. Overall, the impact of acoustic design across both samples emphasises the improvements in workspace design as improvements for all.

5.3. Summary and Implications

The survey within this research encouraged the respondents to personally consider their own workspace (due to the demand of remote working); the data from the survey allowed more succinct and individual responses, understanding the user.

Overall, the aggregation of both qualitative and quantitative data did prove contradictory but resulted in more indicative conclusions, such as the innovative solutions that arose from respondents who had optimised their space across both samples. Many suggested creative solutions to the issue of zoning, suggesting adding curtains to separate the space, or using different desks for different activities. This reinforces the effective practice of learning from the user, identifying what can be incorporated/removed from existing workspaces to productively remove barriers, improve perceptions, and achieve comfortable working conditions. This also enhances a balanced relationship between user and designer; through mutual understanding and influence, a long-term, supportive, and comfortable space can be created and improve the sustainability of the project.

Figure 16 below was created considering the responses and literature, in order to identify the prescriptive and performance needs emerging from this research. Prescriptive relates to key design features, many of which were provided by respondents to the survey alongside the literature, and performance relates to the demands mentioned in the survey and overall drivers for workspace design. This map can act as a guide to reducing barriers and designing workspaces more inclusively, additional to a focus on and dedication to understanding user needs.

Figure 16.

Conclusion map.

5.4. Data Limitations and Bias

During the analysis of the data, it was important to identify potential areas of bias. In the feedback question for the survey, one respondent mentioned that some of the questions seemed similar; this is noticeable from the repetition of the ‘why’ questions. This could lead to habituation bias, where respondents provide similar answers worded in similar ways [87]. This effect was mitigated by shortening the survey to reduce fatigue while making it stimulating enough to prevent the respondent from running out of energy. Nevertheless, this bias can lead to repetition of some of the results—providing further confirmation but an extended analysis time.

There appeared to be wording bias [88], where the wording of a question impacts how a respondent replies. This is likely the case in the examples provided in this survey: e.g., mentioning the movement of furniture with respect to flexibility in the room did appear to impact the responses (see Appendix A for the whole survey). Although the intention was to provide clarity to the question, this appeared to sway the answers. One improvement could be to provide images of typical ‘adaptable spaces’ and allow the respondent to be more visually stimulated (to prevent fatigue) and less influenced by specific words. Some of the questions were also broad; although this prevents survey fatigue, the responses are limited by the restraint implied by the question. For example, having a more response-based survey may be more effective, i.e., if the respondent states lighting as most impactful on their wellbeing, asking more questions specifically related to this. This also suggests a focus group approach; however, this would require more time from the participant.

An alternative method would be the multicriteria decision analysis approach (MCDA) used by Mosca and Capologo in developing a universal design-based framework [10]. This suggests research to be carried out in phases (involving a literature review and workshops with users and experts) that consider social, physical, sensorial, and cognitive design factors. This framework could be used and adapted to the design of workspaces, providing key design factors that can be used by designers to provide applicable and descriptive information [11].

Overall, the stress of the global pandemic swayed many of the responses. This restriction is prominent amongst sample A, and there are many mentions of limited options: ‘no other space’, ‘only place I have’, ‘there’s nowhere else’. Similarly, one respondent mentioned that they would ‘prefer to work at their office…but this is not allowed’. Regardless of spatial barriers, the overall influential factor appears to be a lack of external control of their space. This is reinforced by studies conducted throughout the pandemic surrounding the mental health of students living at home [89,90], showing a strong relationship between poor housing and depressive symptoms, reinstating the importance of interdisciplinary design to achieve better spaces. Furthermore, the following is another limitation of the data: the survey focused on a selection of design features and users, inspired by the literature review; however, questions regarding apartment size, views, and access to open space should also be included, to provide further evidence for the design features [91].

6. Conclusions

Standards and guidance on the design of workspaces include methods to improve productivity and overall comfort but contain limited information on inclusivity.

The social model of disability holds designers responsible for creating or removing the barriers experienced by the user.

Quantitative data from the surveys confirm that lighting and furniture (specifically the ergonomics of furniture) made the greatest contribution to the wellbeing of participants, providing alignment with the literature.

The qualitative survey data present more specific personal needs in relation to individual workspaces, such as the relationship between mobility disabilities and ergonomics, and between neurodivergence and zoning/partitioning. The data also suggest positive responses to room decorations and layout, related to creativity in neurodiversity.

The mixed methods approach highlighted homogeneous responses between both samples and the data; design features such as thermal comfort and acoustics require improvements that would benefit all: e.g., added thermal comfort control and acoustic panelling.

A major factor influencing workplace satisfaction across both samples was the control over one’s environment. Participants used lamps and blinds to control lighting and adjusted the heating to keep them awake and alert. This reinforces the effective method of learning from the user, by identifying user needs and balancing prescriptive and performance factors with thorough inclusion considerations.

The accessibility prominence of this research has been generalised by stopping short of a specific deeper analysis of neurodiversity and disability user needs; this is also due to the limited research surrounding neurodiversity. This lends itself to further research specific to ‘non-mobility’ conditions using focus groups and interviews. Similarly, a thorough case study analysis of responsive workspace design alongside inclusive work environments could be carried out, potentially using a more thorough multi-factor analysis. Furthermore, this research highlights more drivers for workspace design, and thus further research regarding specific design features and their individual impact on zoning or productivity, as well as relevant studies corresponding to neurodivergence, would be beneficial for physical implementation into workspaces.

Overall, the importance of interacting with users and understanding the drivers behind workspace design can provide clear solutions that actively include all users.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.W. and O.P.N.; methodology, O.P.N.; formal analysis, O.P.N.; writing—original draft preparation, O.P.N.; writing—review and editing, M.W., J.T., and O.P.N.; visualisation, O.P.N.; supervision, M.W. and J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the study considered low risk.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Overview of survey questions and types.

Table A1.

Overview of survey questions and types.

| Theme | Survey Question | Question Type |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Context and Overall Use (Context regarding location, what draws them to this space) | In which space listed below does most of your working/studying take place? | Multiple choice |

| Do you vary where you work? | Multiple choice | |

| If you are at home, which space do you mostly work/study in? | Multiple choice | |

| Is this space shared with others? | Multiple choice | |

| How long have you been working/studying in this space? | Multiple choice | |

| Why have you chosen this space? | Open-ended question | |

| Spatial Changes and Individual Use (Regarding specific changes within their space, whether barriers exist that they cannot change) | Have you changed any of the below within your work/study space over the past year? | Checkbox |

| Regarding the previous question, why did you carry out these changes? | Open-ended question | |

| Similarly, are there any specific barriers you continue to experience in your space? | Open-ended question | |

| Wellbeing (Identifying what brings them the most joy and happiness) | Which contributes the most to your wellbeing within your space? | Multiple choice |

| Flexibility/Adaptability (Extending on the barriers question, identifying whether they can change their space based on their needs) | Would you describe your space as flexible/adaptable? i.e., can you adapt it to suit your needs? | Multiple choice |

| If yes, what makes it flexible/adaptable? | Open-ended question | |

| If no, what makes it inflexible/unadaptable? | Open-ended question | |

| Would you benefit from more adaptability in your space? | Multiple choice | |

| Control (Limitations include being in student accommodation, or mobility conditions) | How much control do you have over adapting your space by yourself? | Multiple choice |

| Miscellaneous (Conclusive questions, any final comments) | What works well in your work/study space and why? | Open-ended question |

| Any other comments about your space? | Open-ended question | |

| Demographics (Could be relevant to previous questions regarding control and adaptability) | Do you have any of the below? (This is to further understand any previous preferences mentioned) (relating to specific conditions) | Checkbox |

| Which age range are you in? | Multiple choice | |

| Feedback | Any feedback on the survey? | Open-ended question |

References

- CEM. Inclusive Access, Sustainability and the Built Environment; College of Estate Management: Reading, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- John Clarkson, P.; Coleman, R. History of inclusive design in the UK. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 46, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, K.; de Oliveria Smith, P.; Woodworth, A.V. Programming for Health and Wellbeing in Architecture; Menezes, K., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; Volume 37, ISBN 9780367758844. [Google Scholar]

- Channon, B. Happy by Design; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781000726725. [Google Scholar]

- IWBI. WELL Building Standard Version 1. Delos International Well Building Institute. 2014. Available online: https://resources.wellcertified.com/tools/well-building-standard-v1/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Jean-Baptiste, A. Making Inclusive Design a Priority. 2020. Available online: https://www.porchlightbooks.com/blog/changethis/2020/making-inclusive-design-a-priority (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Greco, A. Social sustainability: From accessibility to inclusive design. EGE Rev. Expresión Gráfica Edif. 2020, 12, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afacan, Y.; Afacan, S.O. Rethinking social inclusivity: Design strategies for cities. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban. Des. Plan. 2011, 164, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, A. Sustainable and inclusive design: A matter of knowledge? Local Environ. 2008, 13, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, E.I.; Capolongo, S. Universal Design-Based Framework to Assess Usability and Inclusion of Buildings. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinform.) 2020, 12253, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, E.I.; Herssens, J.; Rebecchi, A.; Capolongo, S. Inspiring architects in the application of design for all: Knowledge transfer methods and tools. J. Access. Des. All 2019, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, A.; Lindahl, G.; Dell’Ovo, M.; Capolongo, S. Validation of a multiple criteria tool for healthcare facilities quality evaluation. Facilities 2021, 39, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, T.; Pascal, C. Summary of Key Findings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccio, S.; Connelly, C.E.; Gellatly, I.R.; Jetha, A.; Martin Ginis, K.A. The Participation of People with Disabilities in the Workplace Across the Employment Cycle: Employer Concerns and Research Evidence. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 35, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandola, T.; Rouxel, P. The role of workplace accommodations in explaining the disability employment gap in the UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisman-Nitzan, M.; Gal, E.; Schreuer, N. “It’s like a ramp for a person in a wheelchair”: Workplace accessibility for employees with autism. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 114, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadia, T. Exploring the Design Preferences of Neurodivergent Populations for Quiet Spaces. EngrXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soane, A. Independent Review of Building Regulations and Fire Safety—A damning report. Struct. Eng. J. Inst. Struct. Eng. 2018, 96, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wylde, M.A. Building for a Lifetime: The Design and Construction of Fully Accessible Homes/Margaret Wylde, Adrian Baron-Robbins, and Sam Clark; Clark, S., Baron-Robbins, A., Eds.; Taunton Press: Newtown, CT, USA, 1994; ISBN 1561580368. [Google Scholar]

- Imrie, R. The role of the building regulations in achieving housing quality. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DWP Family Resources Survey: Financial Year 2019 to 2020. Gov.Uk. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/family-resources-survey-financial-year-2019-to-2020/family-resources-survey-financial-year-2019-to-2020#disability-1 (accessed on 26 January 2022).

- Bewley, H.; George, A. Research Paper: Neurodiversity at Work; ACAS: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, S.; Smith, C.; Touchet, A. The Disability Perception Gap, Scope. 2018. Available online: https://www.scope.org.uk/campaigns/disability-perception-gap/ (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Salvendy, G. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 4th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780470528389. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield, D. Good Office Design, 1st ed.; Riba Publishing: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781000705171. [Google Scholar]

- Kaarlela-Tuomaala, A.; Helenius, R.; Keskinen, E.; Hongisto, V. Effects of acoustic environment on work in private office rooms and open-plan offices—Longitudinal study during relocation. Ergonomics 2009, 52, 1423–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Id, K.S.; Pachilova, R. Differential perceptions of teamwork, focused work and perceived productivity as an effect of desk characteristics within a workplace layout. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, A. Settlers, vagrants and mutual indifference: Unintended consequences of hot-desking. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2011, 24, 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.L.; Macky, K.A. The demands and resources arising from shared office spaces. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 60, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staines, G.M. Universal Design: A Practical Guide to Creating and Re-Creating Interiors of Academic Libraries for Teaching, Learning, and Research, 1st ed.; Chandos Information Professional Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 9781843346333. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.H.; Wu, F.; Su, B. Impacts of Library Space on Learning Satisfaction—An Empirical Study of University Library Design in Guangzhou, China. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2018, 44, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossaller, J.; Oprean, D.; Urban, A.; Riedel, N. A happy ambience: Incorporating ba and flow in library design. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2020, 46, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Konno, N. The concept of “Ba”: Building a foundation for knowledge creation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1998, 40, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Applications of Flow in Human Development and Education: The Collected Works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. The flow experience and its significance for human psychology. Optim. Exp. 2012, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.C.; Yap, H.S.; Kwok, K.W.; Car, J.; Soh, C.K.; Christopoulos, G.I. The cubicle deconstructed: Simple visual enclosure improves perseverance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooney, C.; Hadjri, K.; Mcallister, K.; Rooney, M.; Faith, V.; Craig, C. Experiencing visual impairment in a lifetime home: An interpretative phenomenological inquiry. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, L. Designing Dementia-Friendly Outdoor Environments. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2004, 7, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzunegui-Eraso, A.; Erro-Garcés, A. Teleworking in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibaldi, C.; McCreedy, R.T.W. The Observed Effects of Mass Virtual Adoption on Job Performance, Work Satisfaction, and Collaboration. In Work from Home: Multi-Level Perspectives on the New Normal; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2021; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- OECD The future of remote work: Opportunities and policy options for Trentino. OECD Local Econ. Employ. Dev. Pap. 2021, 9–10, 25. [CrossRef]

- Atlas CLoud. AtlasCloud Survey: Get Hybrid Working Done Introduction; Atlas Cloud: Newcastle, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Megahed, N.A.; Ghoneim, E.M. Antivirus-built environment: Lessons learned from Covid-19 pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shum, A.; Holmes, K.; Woolery, K.; Price, M.; Kim, D.; Dvorkina, E.; Malekzadeh, S. Inclusive: A Microsoft Design Toolkit. M. Price etc. Microsoft Des. 2016, 32, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Raine, K.D.; Muhajarine, N.; Spence, J.C.; Neary, N.E.; Nykiforuk, C.I.J. Coming to consensus on policy to create supportive built environments and community design. Can. J. Public Health 2012, 103, S5–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.; Rosenberg, D.; Frank, L. The Role of the Built Environment in Healthy Aging: Community Design, Physical Activity, and Health among Older Adults. J. Plan. Lit. 2012, 27, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, A.L.; Boucher, T.M.; Lavelle, A.D. How do you work? Understanding user needs for responsive study space design. Coll. Res. Libr. 2018, 79, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, H.G.; Miles, M.B.; Michael Huberman, A.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis. A methods Sourcebook, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Delİce, A. The sampling issues in quantitative research. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2001, 10, 2001–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.L. Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: A Pragmatic Approach. In Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: A Pragmatic Approach; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walliman, N. The nature of data. In Research Methods: The Basics; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2010; pp. 201–218. ISBN 9781118280249. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, G. Multitasking in the Digital Age. Synth. Lect. Human-Cent. Inform. 2015, 8, 1–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Kee, K.; Mao, C. Multitasking and Work-Life Balance: Explicating Multitasking When Working from Home. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2021, 65, 397–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly-Shah, V.N. Factors influencing healthcare provider respondent fatigue answering a globally administered in-app survey. PeerJ 2017, 2017, e3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stiles, K. Survey Fatigue 101: Everything You Should Know Before Creating Your Next Online Survey. Available online: https://www.surveycrest.com/blog/survey-fatigue-101/ (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Schein, J. Finding a cure for headaches. RDH 1990, 10, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, A. 6 Tips for Creating More Inclusive Surveys | Zendesk. 2020. Available online: https://www.zendesk.co.uk/blog/creating-more-inclusive-surveys/ (accessed on 9 April 2021).

- Shorten, A.; Smith, J. Mixed methods research: Expanding the evidence base. Evid. Based. Nurs. 2017, 20, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yousefi Nooraie, R.; Sale, J.E.M.; Marin, A.; Ross, L.E. Social Network Analysis: An Example of Fusion Between Quantitative and Qualitative Methods. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2020, 14, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using Mixed-Methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, B. Coronavirus and the Impact on Students in Higher Education in England: September to December 2020. Office National Statistics. 2020; pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/educationandchildcare/articles/coronavirusandtheimpactonstudentsinhighereducationinenglandseptembertodecember2020/2020-12-21 (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- CIEHF. What is Ergonomics; Charted Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Helander, M.G. Forget about ergonomics in chair design? Focus on aesthetics and comfort! Ergonomics 2003, 46, 1306–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikdar, A.A.; Al-Kindi, M.A. Office Ergonomics: Deficiencies in Computer Workstation Design. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2007, 13, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Woo, E.H.C.; White, P.; Lai, C.W.K. Ergonomics standards and guidelines for computer workstation design and the impact on users’ health—A review. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Universal Music UK. Creative Differences: A Handbook for Embracing Neurodiversity in the Creative Industries; Universal Music UK: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, M.K. Neurodiversity in the Workplace: Architecture for Autism. Master's Thesis, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Staricoff, R.; Clift, S. Arts and Music in Healthcare; Chelsea and Westminster Health Charity: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Küller, R.; Ballal, S.; Laike, T.; Mikellides, B.; Tonello, G. The impact of light and colour on psychological mood: A cross-cultural study of indoor work environments. Ergonomics 2006, 49, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interface Human Spaces: The Global Impact of Biophilic Design in the Workspace. 2015. Available online: https://greenplantsforgreenbuildings.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Human-Spaces-Report-Biophilic-Global_Impact_Biophilic_Design.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2021).

- Yin, J.; Zhu, S.; MacNaughton, P.; Allen, J.G.; Spengler, J.D. Physiological and cognitive performance of exposure to biophilic indoor environment. Build. Environ. 2018, 132, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapaport, P.; Burton, A.; Leverton, M.; Herat-Gunaratne, R.; Beresford-Dent, J.; Lord, K.; Downs, M.; Boex, S.; Horsley, R.; Giebel, C.; et al. “i just keep thinking that i don’t want to rely on people.” a qualitative study of how people living with dementia achieve and maintain independence at home: Stakeholder perspectives. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, A.; Radel, J.; McDowd, J.M.; Sabata, D. Perspectives of People with Dementia about Meaningful Activities. Am. J. Alzheimers. Dis. Demen. 2016, 31, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, L.; Preez, M.; Raeburn, C. Colour & Wayfinding; Trust Housing Association: Edinburgh, UK, 2016; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Space10. Can We Design Our Way Into Better Mental Health? SPACE10: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriou, E. Wellbeing in Interiors; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pencavel, J.H. Diminishing Returns at Work: The Consequences of Long Working Hours; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 9780190876166. [Google Scholar]

- Partonen, T.; Lönnqvist, J. Bright light improves vitality and alleviates distress in healthy people. J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 57, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, P.R.; Tomkins, S.C.; Schlangen, L.J.M. The effect of high correlated colour temperature office lighting on employee wellbeing and work performance. J. Circadian Rhythm. 2007, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kroner, W.M. An intelligent and responsive architecture. Autom. Constr. 1997, 6, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Senses of place: Architectural design for the multisensory mind. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2020, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, A.; MacLennan, S.J.; Hassard, J. Menopause and work: An electronic survey of employees’ attitudes in the UK. Maturitas 2013, 76, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ou, D.; Kang, S. The effects of masking sound and signal-to-noise ratio on work performance in Chinese open-plan offices. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 172, 107657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.C.; Irvine, K.N.; Bicknell, J.E.; Hayes, W.M.; Fernandes, D.; Mistry, J.; Davies, Z.G. Perceived biodiversity, sound, naturalness and safety enhance the restorative quality and wellbeing benefits of green and blue space in a neotropical city. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 143095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillay, D.; Vieira, B.L. Noise, screaming and shouting: Classroom acoustics and teachers’ perceptions of their voice in a developing country. S. Afr. J. Child. Educ. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mak, C.M.; Lui, Y.P. The effect of sound on office productivity. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2012, 33, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaney, N.; Dixit, A.; Ghosh, T.; Gupta, R.; Bhatia, M. Habituation of event related potentials: A tool for assessment of cognition in headache patients. Delhi Psychiatry J. 2008, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kahle, L.R.; Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 31, ISBN 9780136094234. [Google Scholar]

- Amerio, A.; Brambilla, A.; Morganti, A.; Aguglia, A.; Bianchi, D.; Santi, F.; Costantini, L.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Signorelli, C.; et al. Covid-19 lockdown: Housing built environment’s effects on mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amerio, A.; Bertuccio, P.; Santi, F.; Bianchi, D.; Brambilla, A.; Morganti, A.; Odone, A.; Costanza, A.; Signorelli, C.; Aguglia, A.; et al. Gender Differences in COVID-19 Lockdown Impact on Mental Health of Undergraduate Students. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Berry, L.L.; Quan, X.; Parish, J.T. A conceptual framework for the domain of evidence-based design. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2011, 4, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).