Abstract

The present study investigates the effect of salespeople’s individual sales capabilities on selling behaviors and sales performance in door-to-door personal selling channels. The data are gathered from 219 South Korean salespeople. The hypotheses are tested using the structural equation modeling technique. The study finds that salespeople's individual sales capabilities have a greater impact on customer-oriented selling behavior than sales-oriented selling behavior. Similarly, both sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors have significant positive effects on sales performance. The study also discovers that competitive intensity moderates the relationship between customer-oriented selling behavior and sales performance, but has no significant effect on the relationship between sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance. The current research only looks at door-to-door personal selling channels in South Korea. The implication is that the impacts of individual selling capabilities may differ in other contexts. The current study demonstrates that competitive intensity can reduce the impact that a “customer orientation” has on sales performance, and thus a blend of the two orientations (SOCO) is recommended for desired performance outcomes in the face of competition. Additionally, firms should focus on creating a culture that builds and enriches the sales capabilities of salespeople.

1. Introduction

Most businesses have long prioritized long-term, mutually beneficial, and sustainable customer relationships. These ties improve customer loyalty, business sustainability [1,2,3], and satisfaction [4]. Increased customer loyalty and satisfaction may result in increased sales and profits [5,6]. Few people would deny that firms pursuing long-term relationships have advantages. The relationship between relational selling and customer orientation by boundary-spanning salespeople is well-documented [7,8], with boundary spanning defined as the activity, behavior, and navigation the salesperson engages in with various customers both inside and outside his or her own company [9,10].

The sales-oriented–customer-oriented (SOCO) approach is a common mechanism for analyzing boundary-spanners’ proclivity for relational marketing [11]. Customers are much more likely to form long-term relationships with salespeople who employ a so-called customer-oriented strategy [1,8]. A customer-oriented selling technique focuses on assisting customers in making informed purchasing decisions, and may include measures that prioritize the customer’s best interests over immediate sales and commissions. If a quick, simple transaction can be completed, salespeople who employ a sales-oriented selling strategy may be less concerned with the customer’s interests. Furthermore, most salespeople believe that a sales orientation has a temporal component as opposed to customer orientation [12]. According to this viewpoint, a salesperson who provides better service to their customers or has a customer-oriented mentality will most likely sell more in the long run. This implies that salespeople do more than just sell products to customers; they also assist customers in becoming partners in the company’s profit-making process [13].

Despite the crucial nature of salespeople’s boundary-spanning roles, there appear to be significant gaps in the literature that require scholarly attention. For example, while the salesperson’s strategic boundary-spanning activities necessitate specific individual capabilities, previous research has not focused much on measuring these individual capabilities and how they generate selling behaviors. Similarly, the nature of the selling job requires that salespeople use both customer- and sales-oriented selling methods (behaviors) to achieve their goals. In spite of this, little research has been conducted to determine how salespeople’s SOCO behaviors are influenced by their specific sales capabilities. Additionally, previous research has placed little focus on assessing how customer-oriented and sales-oriented selling behaviors affect sales performance. Finally, while market competitive intensity has been argued to affect firm performance, little attention has been paid to how the competitive intensity of the business environment could affect the relationship between salespeople’s sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors and sales performance.

Accordingly, in filling these gaps, this study aims to model the effects of salespeople’s individual sales capabilities on both sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors. The study also investigates how sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors influence sales performance. Finally, we investigate how the relationships between salespeople’s SOCO behaviors and sales performance are influenced by competitive intensity. While we acknowledge that some research has been conducted on the subject [13,14,15], our study is unique in that it explores how salespeople’s individual sales capabilities influence their sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors. Our study adds to the growing body of knowledge by looking into the roles of sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors in sales performance, as well as the moderating effect of competitive intensity on the same relationship. While the influence of customer-oriented selling behavior on sales performance may be reduced in a competitive market, our findings show that competitive intensity has no significant moderating effect on the effect of sales-oriented selling behavior on sales performance. In effect, our study highlights the fact that, regardless of competition, sales-oriented selling behavior can be applied to improve sales performance.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Resource-Based View

Many marketing studies have used resource-based theory to explain the relationship between a firm’s differentiated competitive advantage and marketing performance [16,17]. According to the resource-based theory, a company’s performance is influenced by its internal resources and capabilities, rather than external factors such as economics or attractiveness [17,18,19]. The theory emphasizes the importance of resources in business. It implies that the organization’s resources are valuable (valued), rare/unique (rare), and inimitable (inimitable) to the point that potential competitors will be unable to obtain them now or in the future. In comparison to competitors’ resources, the emphasis is on acquiring irreplaceable resources or capabilities [17]. The aforementioned characteristics set the organization apart from resources that can be easily transferred and secured to other companies, making it difficult to replicate. Other organizations find it difficult to obtain the same resources due to scarcity, making a truly competitive environment impossible. Barney [17] divides resources into physical, human, and organizational capital based on heterogeneity and immobility. These assets provide a corporation with a long-term competitive advantage rather than a short-term competitive advantage. It emphasizes the importance of human capital as one of the three resources. Traditional resources such as natural resources, technological resources, economies of scale, and so on have historically provided a competitive advantage to an organization, but according to resource-based theory, these resources are easily imitated by competitors and transferred to other resources. Besides, human capital can be defined as a vital component of business success and a source of long-term competitive advantage [20]. Human capital, an intangible but visible resource, is efficiently distributed through education as a source of corporate competitiveness. In the current study, we argue that salespeople’s capabilities are difficult to replicate, and that they are valuable resources that can help a company achieve greater success (sales performance). The resource-based theory has been used in previous research [13,21], and is adopted as the theoretical lens for this study.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Salesperson’s Individual Sales Capability

A systematic study of salesforce capabilities began when the general capability model was seriously researched in the 1990s. Spencer and Spencer [22] are two well-known researchers in the field of salesperson capabilities who are frequently quoted. Spencer and Spencer [22] used the capability model to categorize individual capabilities by job type—technical/professional, sales, and interpersonal service—and then compared the capabilities and behaviors of excellent and average performers by grouping them into individual employees and managers. According to their findings, the competency of excellent salespeople varies depending on the length of the business cycle, complexity, company regional features, products, and customer types. Control, goal-oriented behavior, initiative, and interpersonal skills are all factors that influence the capabilities required of salespeople [23]. Understanding, customer orientation, confidence, relationship development, analytical thinking, conceptual thinking, information establishment, organizational awareness, and technical experience are all identified as important selling skills. Among other things, this sales capability contributes significantly to performance generation and improvement. It is the most faithful and appropriate capability for the organization’s goal at the organizational level, and it is the capability best suited for individual duties or responsibilities at the individual level [24]. Previous research has identified a number of specific elements that comprise a salesperson’s sales capability. Michaels and Marshall [25], for example, recommended that salespeople understand their clients in order to plan strategically and systematically for tactical sales operations. According to Warech [26], key constituents of sales capability include customer partnership, relationship formation, communication, customer and quality orientation, learning motivation, achievement orientation, interpersonal skills, internal resources and network utilization, technical capabilities such as management ability, and problem-solving ability. The ability of an individual or organization to achieve good performance or gain a competitive advantage through sales is referred to as sales capability [13,27]. It is difficult to duplicate because it is a one-of-a-kind and intrinsic ability.

It is also more difficult to imitate because it consists of core know-how, knowledge, and technology, and it is not the result of an individual or an organization, but rather a natural trait. Within sales organizations, it can be argued that ensuring salespeople have a high level of sales capability is crucial, with extant sales research arguing that, effective and strategic sales activities can improve sales performance and, consequently, management performance [28,29].

2.2.2. Sales-Oriented and Customer-Oriented (SOCO) Behaviors

The SOCO scale was developed by Michaels and Marshall [25] to assess the two ways salespeople interact with customers: sales orientation (SO) and customer orientation (CO). Customer orientation is defined as the degree to which salespeople seek to assist customers in making satisfied purchase decisions, thereby putting the marketing concept into action, whereas sales orientation is defined as a selling technique that aims to sell as much to customers as possible. Customer-oriented salespeople are interested in learning how to understand consumers by paying attention to their needs and then providing the best solutions to those problems, rather than simply making sales. Short-term gain sales-oriented salespeople, on the other hand, seek to maximize their profits as soon as possible [11,30,31]. Understanding these two concepts, however, is vital for understanding that a high level of customer orientation does not always imply a low level of sales orientation. People are motivated by incentives such as concern for others, as well as motives to pursue one’s own interests and altruistic tendencies [32,33]. In this regard, customer and sales orientations are not mutually exclusive.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Individual Sales Capability of Door-to-Door Salesperson and SOCO

According to Spencer and Spencer [22], capability is an indicator of the behavior and mentality that employees must consistently exhibit to function in a variety of job-related scenarios. It is defined as a set of technical attitudes or indicators that can be improved and quantified through continuous development and performance in critical areas, with capability focusing on the specific behavioral traits of individuals in the work process [24]. Specific activities undertaken while performing work, as well as the professional knowledge, talents, personality, and attitude of the individual, are regarded as necessary to foster good capabilities [34]. Individual capabilities, such as knowledge and skills, influence individual behavior in the development of high-quality products and services, which leads to improved organizational performance [35]. We contend that individual capability within an organization influences performance through individual behaviors, which is consistent with previous research [35]. We argue that the selling behavior of the salesforce reveals their individual sales capability in the sales organization.

Spencer and Spencer [22] developed a rigorous criterion for the job capability required to meet organizational goals, and discovered that achievement orientation and influence are the most important sales capabilities. Michaels and Marshall [25] reckoned that it is essential to provide training for sales personnel who must perform long-term sales activities based on factors such as customer management capability, relationship formation ability, ability to prepare for business visits, communication skills, ability to establish long-term customer relationships, and information gathering ability. Individual sales capability is highlighted more than variables for achieving short-term sales performance when it comes to customer management, customer relationship creation, and long-term relationship aspects. Instead of focusing on short-term sales outcomes, the corporate side focuses on organizational strengths to consolidate existing customer relationships. Strong salespeople are concerned with short-term sales, but the organization is more concerned with long-term customer relationships. Long-term relationship awareness is particularly important for salespeople in the personal selling market, which values customer relationships, as well as for sales organizations that use customer relationship indicators as performance indicators to encourage salespeople’s customer-oriented selling behavior [36]. The following hypothesis is proposed based on the foregoing:

H1a.

Cosmetic door-to-door salespersons’ individual sales capabilities will have a positive effect on customer-oriented selling behavior.

H1b.

Cosmetic door-to-door salespersons’ individual sales capabilities will have a positive effect on sales-oriented selling behavior.

H2.

Cosmetic door-to-door salespersons’ individual sales capabilities will have a stronger positive effect on customer-oriented selling behavior.

3.2. SOCO and Sales Performance

Our model is based on the basic logic advocated by Saxe and Weitz [11] and others who have contributed to the rich stream of SOCO research [37,38], that each of the perspective’s two constituent components—a sales orientation and a customer orientation—should have an impact on sales performance. Actual sales volume data are used in this study to evaluate sales performance. We used a three-month sales volume for this study and argue that customer orientation should improve sales performance because the salesperson considers the customer’s wants and best interests, as described in previous SOCO discussions. Similarly, while most previous research has argued for a negative relationship between sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance, claiming that salespeople sacrifice the customers’ primary needs and demands to satisfy their own interests (e.g., making a quick sale, getting a commission, etc.), this research asserts the opposite. Both selling behaviors, we believe, are important for improving performance and can occur in the same salesperson. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3.

Customer-oriented selling behavior will have a positive effect on sales performance.

H4.

Sales-oriented selling behavior will have a positive effect on sales performance.

3.3. The Moderating Role of Competitive Intensity on the Relationship between SOCO and Sales Performance

At the organizational level, competitive intensity is influenced by competitors’ perceptions of the external market environment. It is defined as a competitor’s ability to influence the actions of a focal enterprise [39]. Businesses must become more inventive in terms of products and processes in order to succeed as the level of competition rises. When competition is limited, firms, according to Auh and Menguc [40], can utilize their current mechanisms to fully capitalize on the transparent predictability of their own behavior. Firms, on the other hand, will have to adapt in the face of increased competition. Hence, the level of competition in an organization’s external environment can have a significant impact on how effective its process management efforts are.

Thus, organizational procedures must reflect the environment. According to Lawrence and Lorsch [41], organizational efficiency is determined by the degree of fit between an organization’s structure and operations and its environment. The key principle of this contingency theory is that for an organization’s operations to be effective, they must be appropriate for its environment [42]. In a dynamic environment, existing structures and processes may no longer be appropriate, and organizational performance may suffer as a result. Organizations must undergo change in order to achieve the required level of fit to improve their performance and remain competitive [43]. Organizations that compete on price or differentiation face volatile competitive conditions [44]. Competitive pressures exist in a variety of strategic settings, necessitating an understanding of the competitive environment and the selection of the most effective processes in that context.

Accordingly, we contend that, while customer- and sales-oriented selling behaviors can positively influence sales performance, the level of competitive intensity in the corporate environment can have a significant impact on this nexus. We argue that competitive intensity can weaken the relationship between SOCO and sales performance, and we propose the following hypotheses:

H5a.

Competitive intensity will moderate the relationship between customer-oriented selling behavior and sales performance.

H5b.

Competitive intensity will moderate the relationship between sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance.

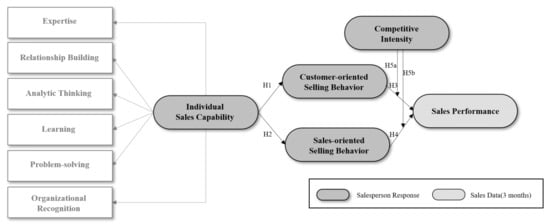

3.4. Research Model

The current study investigates the impact of a salesperson’s individual sales capabilities on sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors (SOCO), as well as how SOCO affects sales performance. The study also examines how competitive intensity moderates the relationship between SOCO and sales performance. Figure 1 depicts this:

Figure 1.

Research model.

4. Methodology

4.1. Context of the Study

South Korea’s cosmetics market is the world’s eighth largest, with an average annual growth rate of 16% between 2012 and 2016, more than five times the average annual growth rate of the Korean economy of 3% during the same period [13,45]. Because of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) controversy and a decrease in Chinese tourists in 2017, the cosmetics industry’s growth has slowed slightly in recent years. South Korean cosmetics exports, on the other hand, increased to USD 5.32 billion in 2019 from USD 4.92 billion the previous year. South Korea’s beauty and personal care market was expected to generate approximately USD 11,500 million in revenue by 2020 [13,46]. The rate of entry and expansion is increasing, and large brands are expanding into Asian countries, particularly China, demonstrating that this is a profitable industry.

4.2. Sampling and Data Collection

Data from South Korean cosmetics brands were used in this study. The study was based on the responses of 219 salespeople from Amore Pacific and LG Household & Health Care, South Korea’s two largest cosmetic manufacturers. As of 2020, the two companies ranked 16th and 12th in terms of global cosmetics company sales, indicating that the issue of sample representativeness has been addressed to some extent. Random sampling was used in this study on salespeople dispatched to the regional headquarters of two companies in Daegu-Gyeongbuk. Because commuting is free in door-to-door selling, non-random sampling is difficult to implement; therefore, the authors used random sampling because there are many door-to-door salespeople who only enlisted as salespeople and have no actual sales. To reduce measurement errors, a measurement tool known for its reliability in previous studies was used, and team leaders (all with PhDs in business administration) reviewed the questionnaire in advance to reduce any ambiguity in the measurement instruments. The questionnaire was administered twice. The first data collection period was from August to December 2020, and the second was from January to February 2021, both of which were face-to-face.

4.3. Profile of Respondents

The demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. In terms of their ages, 6.0% were between the ages of 30 and 39, 22.8% were between the ages of 40 and 49, 54.3% were between the ages of 50 and 59, and 16.9% were over 60. When asked how long they had been at their current job, 6.8% said they had been there for 1–3 years, 19.2% for 3–5 years, 42.0% for 5–7 years, and 32.1% for more than 7 years. In terms of job title, 42.9% identified as junior/senior, 42.0% as masters, and 15.1% as chief masters. In terms of education, 32.4% completed high school, 27.8% completed university, and 39.7% completed graduate school. In terms of prior work experience, 11.4% claimed to have worked in an office/sales environment, 56.2% claimed to be housewives, and 33.5% claimed to be self-employed. When asked why they chose to work at their current firm, 27.8% cited the corporate/product image, 15.5% cited the company’s corporate marketing skills, and 56.6% cited personal recommendations.

Table 1.

Description of respondents.

4.4. Measurement of Variables

The current study used a quantitative approach, including structured questionnaires. This approach is important in theory because it allows for the empirical examination of actual statistical measurements of proposed hypotheses [47]. Individual sales capability, customer-oriented selling behavior, sales-oriented selling behavior, sales performance, and competitive intensity are all evaluated in the survey questionnaire. The construct statements were rated on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree, and 3 = neutral. Items for individual sales capability were adapted from Spencer and Spencer [22], items for customer- and sales-oriented selling behaviors from Saxe and Weitz [11], sales performance items from [48], and competitive intensity items from Jaworski and Kohli [49]. Specifically, competitive intensity was measured with the following scale items adapted from Jaworski and Kohli [49]: CI1—Competition in our market is cut-throat; CI2—There are many “promotion wars” in our market; CI3—Price competition is a hallmark of our market; CI4—One hears of a new competitive move in our market frequently. The scale development and purification methodologies and processes proposed by DeVellis [50], specifically those for confirmatory factor analysis, were used to purify all scale items.

4.4.1. Common Method Bias

To avoid common method bias, the data for this investigation came from two sources [51]. Salespeople completed a questionnaire about their individual sales capability, customer-oriented selling behavior, sales-oriented selling behavior, and competitive intensity, and we evaluated sales performance using real sales data from the previous three months from the respondents.

4.4.2. Test for Non-Response Bias

As Armstrong and Overton [52] suggested, we tested for non-response bias by comparing early and late responders on work experience, employment position, education, and firm name. Second, we looked for differences in the study’s factors between the two groups. There were no statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in either case.

4.5. Reliability and Validity Test

The loadings and their respective and matching constructs were used to assess the measurement items’ reliability [53]. Standard estimates varied from 0.547 to 0.928, with the majority of associated internal consistency values (Cronbach’s alpha) exceeding the 0.7 criterion, according to the findings (see Table 2). The fit indices were: χ2 =757.692, df = 357, χ2/df = 2.12, RMR = 0.030, GFI = 0.817, NFI = 0.843, IFI = 0.910, TLI = 0.897 and CFI = 0.909, in line with Anderson and Gerbing [54]. Table 2 also provides the average variance extracted (AVE). The AVE values varied from 0.506 to 0.753. By comparing AVE values and squared phi correlations between construct pairs, the authors were able to evaluate discriminant validity. In every instance, the AVE values were greater than the shared squared phi correlations between each pair of constructs. This implies discriminant validity, in keeping with Fornell and Larcker [53], which signifies that the constructs are distinct from one another. Each measure’s composite reliability likewise exceeded the 0.7 threshold for acceptable reliability [55].

Table 2.

Reliability and validity analysis of variables.

4.6. Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

Table 3 displays the correlation matrix as well as descriptive statistics. As indicated in the table, the correlation coefficients ranged from 0.106 to 0.697. At both the 0.05 and 0.01 significance levels, correlations were determined to be significant.

Table 3.

Descriptive and correlation analysis.

4.7. Hypothesis Test

As shown in Table 4, the structural model fit indices provided ample evidence of good model fit (χ2 = 596.010, df = 282, χ2/df = 2.11; RMR = 0.032, GFI = 0.840, NFI = 0.859, IFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.907, CFI = 0.919).

The researchers discovered a strong positive link between individual sales capability and customer-oriented selling behavior after conducting structural equation modeling analysis (β = 0.802, p < 0.01). According to the findings, individual sales capability has a significant positive effect on sales-oriented selling behavior (β = 0.558, p < 0.01). In this study, we used a path coefficient value difference analysis to test the hypothesis that individual sales capability has a stronger influence on customer-oriented selling behavior than on sales-oriented selling behavior. The difference in path coefficient values between the unconstrained and constrained models of individual sales capability, customer-oriented selling, and sales-oriented selling behavior was found to be statistically significant, with a Δχ2 value of 4.181.

There was also a significant positive relationship between customer-oriented selling behavior and sales performance (β = 0.256, p < 0.01), as well as a significant positive relationship between sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance (β = 0.239, p < 0.01). Table 4 summarizes these findings.

Table 4.

Model fit and hypothesis test.

Table 4.

Model fit and hypothesis test.

| H | Path | St. Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | Δχ2(1) | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | H2 | Sales capability → customer-oriented sales behavior | 0.802 ** | 0.23 | 6.491 | 4.181 | Supported |

| H1b | Sales capability → Sales-oriented sales behavior | 0.558 ** | 0.199 | 5.604 | Supported | ||

| H3 | Customer-oriented sales behavior → Sales performance | 0.256 ** | 0.077 | 3.468 | - | Supported | |

| H4 | Sales-oriented sales behavior → Sales performance | 0.239 ** | 0.071 | 3.269 | - | Supported | |

** p < 0.01; Model fit: χ2 = 596.010, d.f. = 282, RMR = 0.032, GFI = 0.840, NFI = 0.859, IFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.907, CFI = 0.919.

Moderation Analysis

Hypothesis 5 (a and b) were tested using AMOS in a multi-group analysis to see if competitive intensity had a moderating effect on the relationship between SOCO and sales performance. As shown in Table 5, multi-group analysis is one of the most widely used methods for comparing two groups. The moderating variables are divided into two groups, and the difference between them is calculated to ensure group homogeneity and inter-group heterogeneity. Using multi-group analysis, the difference in χ2 between the unconstrained and constrained models exceeded the threshold value of 3.84 in regard to H5a. In relation to H5b, the difference in χ2 between the constrained and unconstrained models was less than 3.84 (the threshold value). Hence, with the exception of H5b, all of the hypotheses proposed in this study were supported.

Table 5.

Results of multi-group analysis: moderating effect of competitive intensity.

5. General Discussions

5.1. Summary of Findings and General Discussions

The goal of this study was to examine how individual salespeople’s sales capability influenced sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors (SOCO), as well as how these behaviors predicted sales performance. The study also investigated the role of competitive intensity in moderating the relationship between SOCO and sales performance. Overall, the study discovered that individual salespeople’s sales capabilities are germane to both sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors. This finding lends credence to the claim of [13] that salespeople’s individual sales capabilities have a significant impact on their sales- and customer-oriented selling behaviors. This finding also supports the claim of Michaels and Marshall [25] that individual salespeople’s SOCO behaviors are primarily influenced by their selling capabilities. In effect, this study confirms that both sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors require individual selling capabilities.

The research further finds that both sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors have positive and significant effects on sales performance. This finding reinforces the claim of Thakor and Joshi [56] that, while sales-oriented selling behavior is temporary, it has a significant impact on sales performance. These findings further support the assertion of Plouffe et al. [57] that SOCO improves sales performance. The study also discovered that when competition is high, the effect of customer-oriented selling behavior on sales performance is reduced. In other words, customer-oriented selling behavior has a lower impact on sales performance in a highly competitive market. On the other hand, competitive intensity had no significant moderating effect on the relationship between sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance. Essentially, this means that regardless of the level of competition, sales-oriented selling behaviors can be used to improve sales performance. This result may be explained by the position of Yi et al. [13] that sales-oriented selling behavior is short-term in nature, and thus competitive intensity may not affect its effect on sales performance.

Overall, this study improves our understanding of the critical role that salespeople’s unique sales capabilities play in sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors, as well as how these behaviors influence sales performance. Our study finds that salespeople’s individual sales capabilities underpin their SOCO behaviors, and their SOCO behaviors boost sales performance. The study also discovers that competitive intensity has a moderating effect on the relationship between customer-oriented selling behavior and sales performance, but has no effect on the sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance nexus. Specifically, the authors hypothesized that high competitive intensity would reduce the influence of SO on sales performance. Unfortunately, the results of this study were not statistically significant (but when the competitive intensity was low (β = 0.232), SO had a greater effect on sales performance). Accordingly, the researchers’ hypothesis is thought to be consistent with the empirical results, but we believe that these results were derived due to the small sample size. Cosmetics door-to-door sales representatives may also sell cosmetics through online shopping malls or SNS channels in some cases. In other words, because salespeople can use multiple channels, the intensity of competition may not always have a significant impact.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

The current study advances theory by applying resource-based theory to sales capabilities and selling behaviors. In the existing literature, there are few studies that have applied resource-based theory to sales capabilities and selling behavior. Hence, our research contributes to the resource-based literature [17,19] by providing empirical evidence for SOCO behavior using a conceptual model with high explanatory power. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of research in the sales literature that contains and assesses the relationships among the constructs in the study. Prior research examined these dimensions either alone or in conjunction with other variables [22,24,58], emphasizing the importance of new and fresh empirical investigation, validation, and theory development. The study’s focus on the South Korean cosmetics industry, specifically door-to-door cosmetics salespeople, allows us to better understand the complexities of selling in this industry. The study adds to the small number of sales studies that have investigated how salespeople’s capabilities can be transferred. Additionally, our study has established that because both sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors improve sales performance, the two can occur concurrently in the same salesperson, adding to the theory.

5.3. Practical Implications

According to the findings of this study, measuring customer and sales orientations is important not only at the business level, but also at the individual salesperson level. We show that having a customer-oriented ideology or a desire to be customer-oriented is insufficient to produce the desired sales outcomes, and that the salesperson must have a required blend of customer and sales orientation. Furthermore, we hypothesized, and the data support our hypothesis, that competitive intensity is central (moderating effect) in translating the benefits of customer-oriented selling behavior to sales performance, but it does not necessarily change the relationship between sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance.

The findings of this study have important practical implications. First, the fact that individual sales capability influences both sales-oriented and customer-oriented selling behaviors in door-to-door salespeople implies that both selling orientations can coexist in the same salesperson. However, further investigation reveals that salespeople’s individual sales capability has a greater impact on customer-oriented selling behavior. This implies that activities aimed at better understanding the organization and its strategies are required.

Moreover, because customer-oriented selling behavior improves sales performance, door-to-door salespeople, as well as all salespeople in general, should adopt it. Similarly, due to its profitability and the study’s finding that sales-oriented selling behavior improves sales performance, it is necessary to induce sales by combining customer-oriented and sales-oriented selling behaviors in the company.

Besides this, the fact that competitive intensity moderates the relationship between customer-oriented selling behavior and sales performance, but not the relationship between sales-oriented selling behavior and sales performance, implies that competitive intensity mitigates the impact of customer-oriented selling behavior on sales performance. In other words, customer-oriented selling behavior has a lower impact on sales performance in a competitive market, whereas competitive intensity has no effect on the impact of sales-oriented selling behavior on sales performance. In effect, regardless of the level of competition, sales-oriented selling behavior can be used to boost sales performance, emphasizing the importance of strategically blending the two behavioral orientations.

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The research offers some novel and intriguing insights into the factors that influence multidimensional selling behavior and performance. However, there are some constraints to the work. Because the cosmetics companies in this study sell door-to-door in South Korea, the regional and cultural environment may have an impact on the organization’s sales capabilities, limiting generalizability. Therefore, future research should broaden the range of companies used across the country to increase the likelihood of generalization.

Second, the authors used a relatively small sample size of 219 respondents for this study, implying that more research is needed to increase the generalizability of the study results by increasing the sample size. More research is required to support and validate the current study’s construct linkages and conclusions, as businesses’ strategic alignments and orientations may vary depending on the context.

Moreover, while sales performance was defined in this study as the amount of sales made by respondents over three months, three months can be a very short time to investigate the relationship between SOCO and sales performance. Accordingly, it is important to consider whether these indicators can truly be used to predict salespeople’s long-term performance. Hence, to improve the variables’ measurement validity, future studies will need to look at the sales amount for more than one year.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-T.Y. and F.E.A.; formal analysis, H.-T.Y.; funding acquisition, H.-T.Y.; investigation, F.E.A.; methodology, H.-T.Y. and F.E.A.; project administration, F.E.A.; resources, F.E.A.; software, H.-T.Y.; supervision, H.-T.Y. and F.E.A.; writing—original draft, F.E.A.; writing—review and editing, H.-T.Y. and F.E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant no. NRF-2020S1A5A8044884).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact only information about the respondents were used and did not involve using parts of humans or animals or any form of laboratory experiment.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to its classified nature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amenuvor, F.E.; Basilisco, R.; Boateng, H.; Shin, K.S.; Im, D.; Owusu-Antwi, K. Salesforce output control and customer-oriented selling behaviours. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, F.R.; Schurr, P.H.; Oh, S. Developing buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, G.B.; Munir, A.R.; Tamsah, H.; Mustafa, H.; Yusriadi, Y. The Influence of Digital Marketing and Customer Perceived Value Through Customer Satisfaction on Customer Loyalty. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2021, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneshwaran, S.R.; Mathirajan, M. A Theoretical Framework for Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty at Automobile After Sales Service Centres. Int. J. Innov. Manag. Technol. 2021, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Redjeki, F.; Fauzi, H.; Priadana, S. Implementation of Appropriate Marketing and Sales Strategies in Improving Company Performance and Profits. Int. J. Sci. Soc. 2021, 3, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.J.; Kumar, V. Customer Lifetime Duration: An Empirical Framework for Measurement and Explanation; INSEAD: Fontainebleau, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Frankwick, G.L.; Porter, S.S.; Crosby, L.A. Dynamics of relationship selling: A longitudinal examination of changes in salesperson-customer relationship status. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2001, 21, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, R.J.; Good, D.J. Impact of the consideration of future sales consequences and customer-oriented selling on long-term buyer-seller relationships. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2000, 15, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, J.; Alavi, S.; Linsenmayer, K. From personal to online selling: How relational selling shapes salespeople’s promotion of e-commerce channels. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. Striking a Balance in Boundary-spanning Positions: An Investigation of Some Unconventional Influences of Role Stressors and Job Characteristics on Job Outcomes of Salespeople. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, R.; Weitz, B.A. The SOCO scale: A measure of the customer orientation of salespeople. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachner, T.; Plouffe, C.R.; Grégoire, Y. SOCO’s impact on individual sales performance: The integration of selling skills as a missing link. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.T.; Cha, Y.B.; Amenuvor, F.E. Effects of Sales-Related Capabilities of Personal Selling Organizations on Individual Sales Capability, Sales Behaviors and Sales Performance in Cosmetics Personal Selling Channels. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, F.; Ladik, D.M.; Marshall, G.W.; Mulki, J.P. A meta-analysis of the relationship between sales orientation-customer orientation (SOCO) and salesperson job performance. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2007, 22, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.T.; Yeo, C.K.; Amenuvor, F.E.; Boateng, H. Examining the relationship between customer bonding, customer participation, and customer satisfaction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.; Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. The resource-based view of strategy: Origins, implications, and prospects. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 97–211. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, P.R. Toward a general theory of competitive rationality. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D.; Morgan, R.M. The comparative advantage theory of competition. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Wright, P.M. On becoming a strategic partner: The role of human resources in gaining competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1998, 37, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukaatmadja, I.; Yasa, N.; Rahyuda, H.; Setini, M.; Dharmanegara, I. Competitive advantage to enhance internationalization and marketing performance woodcraft industry: A perspective of resource-based view theory. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 6, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.M.; Spencer, P.S.M. Competence at Work Models for Superior Performance; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.S.; Hussain, B.; Hassan, H.; Synthia, I.J. Optimisation of knowledge sharing behaviour capability among sales executives: Application of SEM and fsQCA. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.P.; Martins, T.S. Sales capability and performance: Role of market orientation, personal and management capabilities. Rev. Adm. Mackenzie 2020, 21, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, R.E.; Marshall, G.W. Perspectives on selling and sales management education. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2002, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warech, M.A. Competency-based structured interviewing: At the Buckhead Beef Company. Cornell Hotel. Restaur. Adm. Q. 2002, 43, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G. Development of a Research Model to Analyze the Importance of NPD Capability and Sales Capability to Manage Innovation and to Improve Innovation Outcomes in SMEs. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual Irish Academy of Management Conference 2017, Belfast, Ireland, 30 August-1 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Oliver, R.L. Perspectives on behavior-based versus outcome-based salesforce control systems. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravens, D.W.; Ingram, T.N.; LaForge, R.W.; Young, C.E. Behavior-based and outcome-based salesforce control systems. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenuvor, F.E.; Yi, H.T.; Boateng, H. Examining the consequences of adaptive selling behavior by door-to-door salespeople in the Korean cosmetic industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.E.; le Bon, J.; Rapp, A. Gaining and leveraging customer-based competitive intelligence: The pivotal role of social capital and salesperson adaptive selling skills. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.S.; Amenuvor, F.E.; Boateng, H.; Basilisco, R. Formal salesforce control mechanisms and behavioral outcomes. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 924–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Bergami, M.; Marzocchi, G.L.; Morandin, G. Customer–organization relationships: Development and test of a theory of extended identities. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyatzis, R.E. The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, S.B. The quest for competences: Competency studies can help you make HR decision, but the results are only as good as the study. Training 1996, 33, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Amenuvor, F.E.; Yi, H.T.; Boateng, H. Antecedents of adaptive selling behaviour: A study of the Korean cosmetic industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Widing, R.E.; Coulter, R.L. Customer evaluation of retail salespeople utilizing the SOCO scale: A replication, extension, and application. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1991, 19, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, R.E.; Day, R.L. Measuring customer orientation of salespeople: A replication with industrial buyers. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 22, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W.P. The dynamics of competitive intensity. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 128–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auh, S.; Menguc, B. Balancing exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of competitive intensity. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1652–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.R.; Lorsch, J.W. Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1967, 12, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazin, R.; van de Ven, A.H. Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 1985, 30, 514–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L. The Contingency Theory of Organizations; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Industry structure and competitive strategy: Keys to profitability. Financ. Anal. J. 1980, 36, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Health Industry Promotion Agency. 2016 Cosmetic Industry Analysis Report. 2017. Available online: https://khiss.go.kr/board/view?pageNum=6&rowCnt=10&no1=402&linkId=64102&menuId=MENU00308&schType=0&schText=&boardStyle=&categoryId=&continent=&schStartChar=&schEndChar=&country= (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Choedon, T.; Lee, Y.C. The effect of social media marketing activities on purchase intention with brand equity and social brand engagement: Empirical evidence from Korean cosmetic firms. Knowl. Manag. Res. 2020, 21, 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, F.E.; Dunning, K.E.; Morden, D.L.; Hagan, C.M.; Baker, T.E.; McKay, I.S. Management practice, organization climate, and performance: An exploratory study. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1997, 33, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, M.V.; Joshi, A.W. Motivating salesperson customer orientation: Insights from the job characteristics model. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouffe, C.R.; Hulland, J.; Wachner, T. Customer-directed selling behaviors and performance: A comparison of existing perspectives. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2009, 37, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.T.; Fortune, A.E.; Yeo, C.K. Investigating Relationship between Control Mechanisms, Trust and Channel Outcome in Franchise System. J. Distrib. Sci. 2019, 17, 67–81. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).