Living Amidst the Ruins in Rome: Archaeological Sites as Hubs for Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

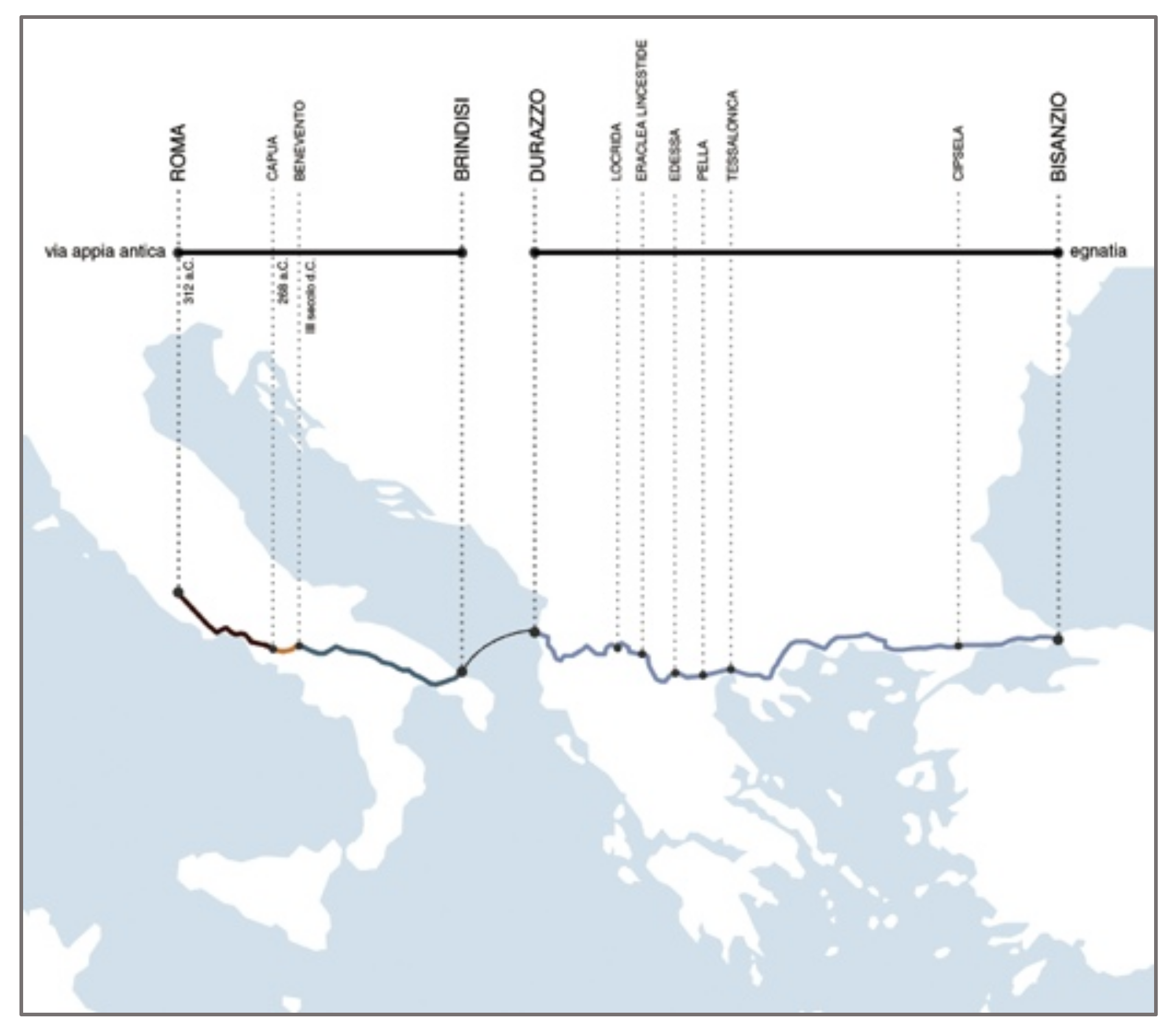

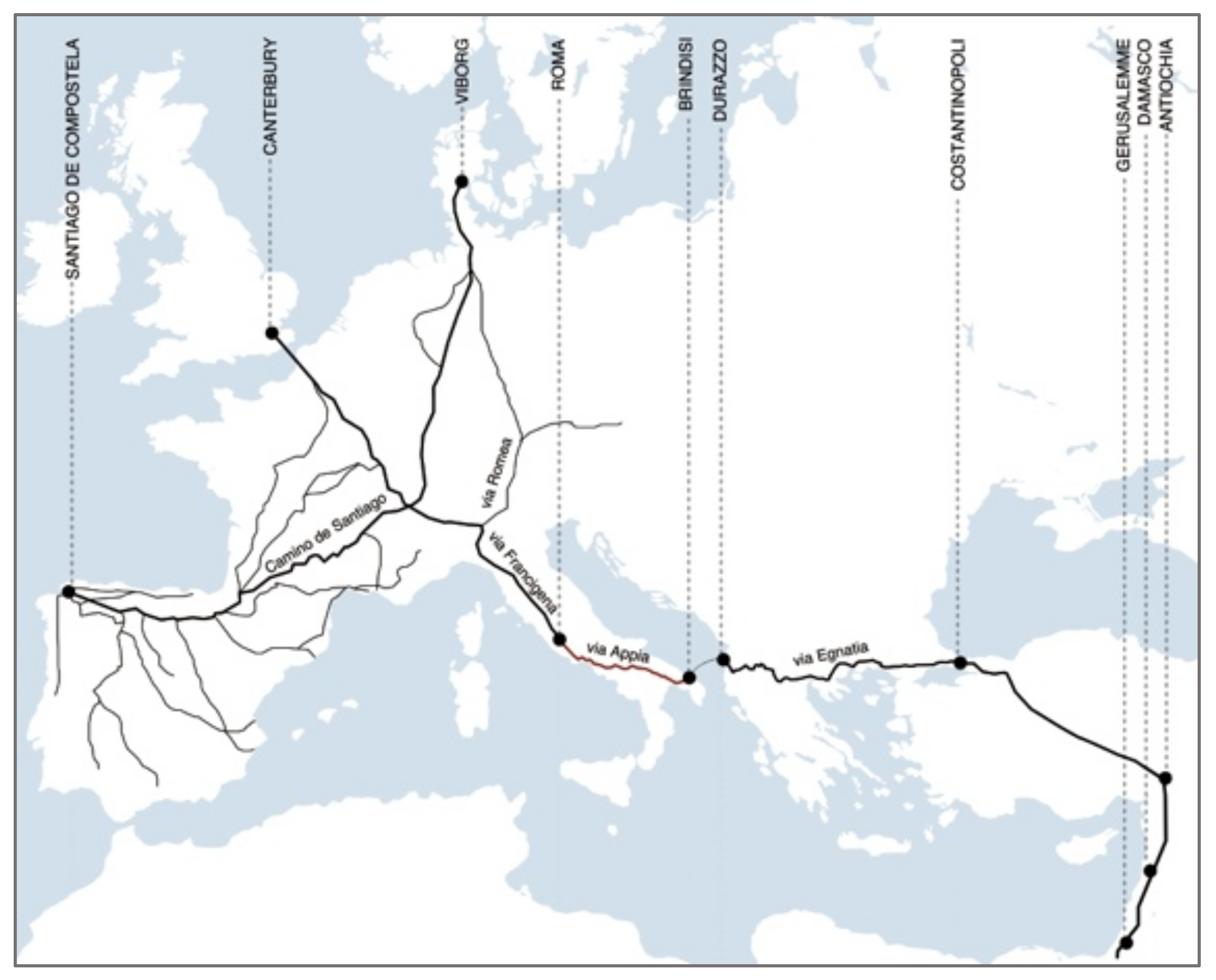

1.1. Antecedent

1.2. Archaeology, Porosity, Networks and Enclaves: The Four Ecologies of Rome

1.2.1. Archaeology for the Re-Semantization of the Past

1.2.2. Porosity for Nature Conservation and Biodiversity

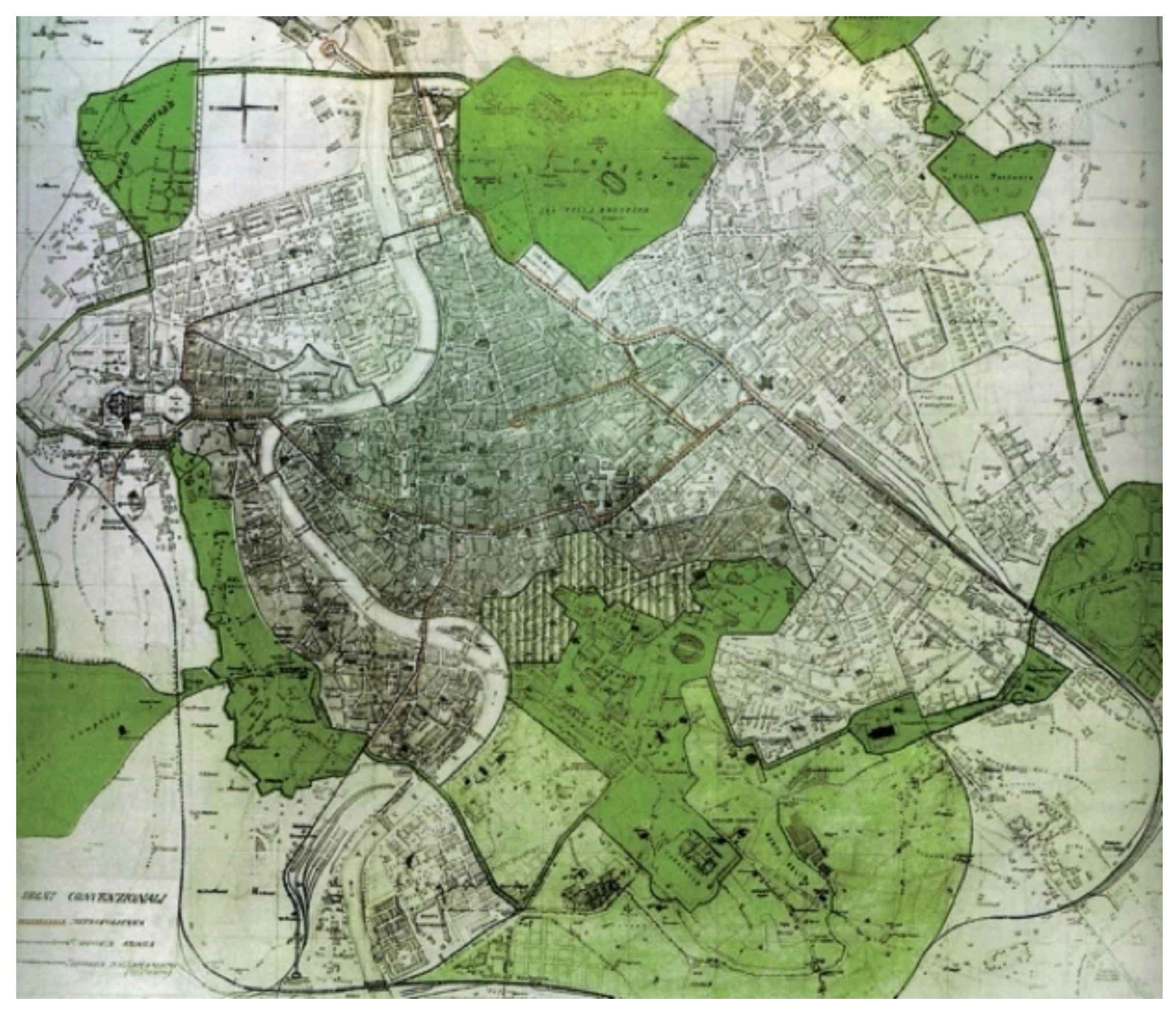

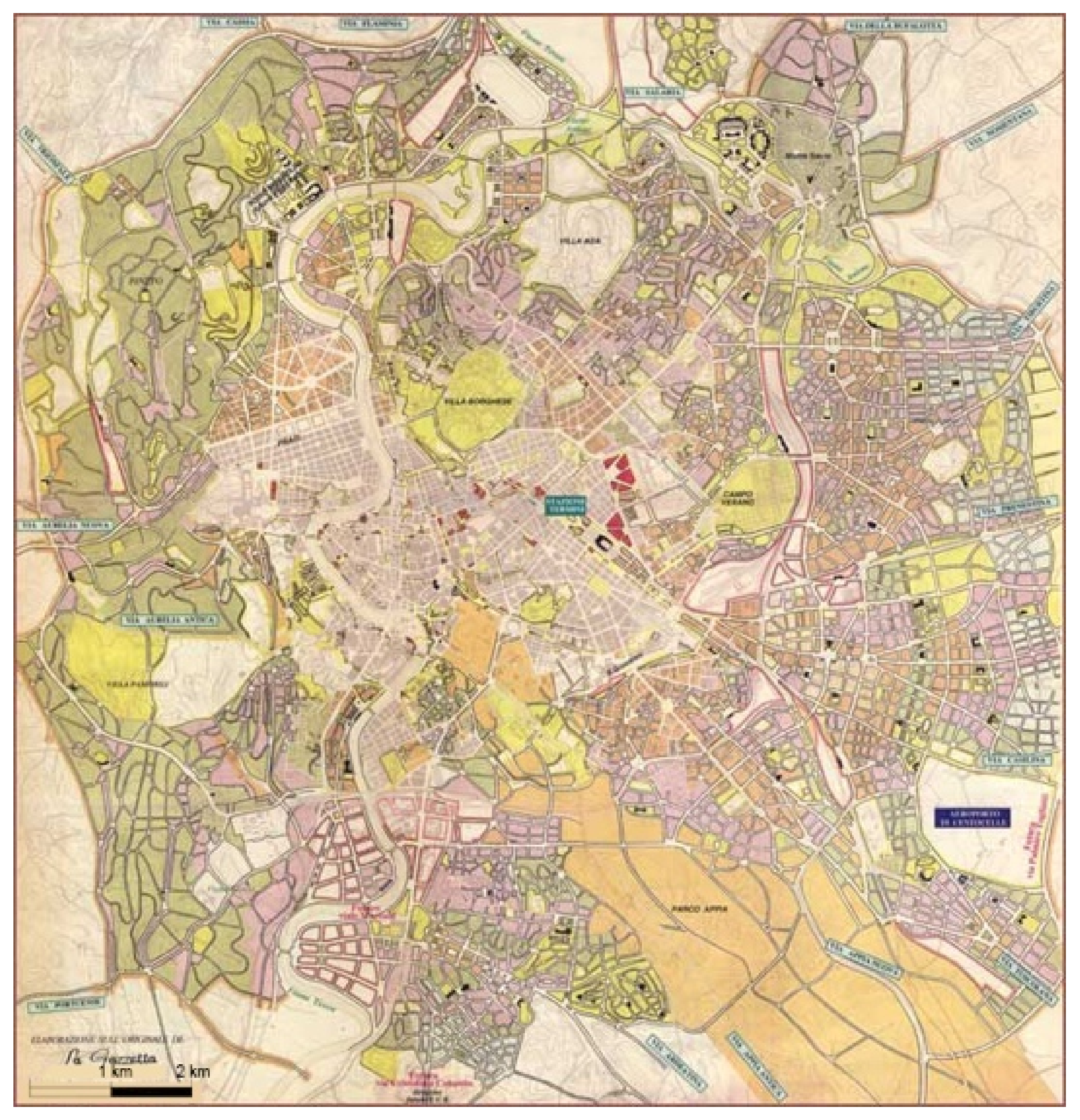

(…) the natural environment has played an important role in conditioning the urban development of Rome, already from the republican era. Later the monuments have often had the effect of preserving green areas, protected from the intense urban development of the last two centuries; these green areas (in particular the large parks of the patrician villas) join the course of the Tiber and therefore the archaeological wedge that develops from the Roman Forum to the Appian Way. In this manner, the whole city is crossed by a green belt that allows faunistic (e.g., for mammals) and also floristic exchanges. Inside the city a sort of urban ecological network is maintained, which is unusual in large European and Mediterranean cities, and which has an important focal point in the archaeological areas.

1.2.3. Networks and Green Corridors as Wellness Infrastructures

1.2.4. Enclaves for Sociality and Culture

1.2.5. Rome and Its Morphology

1.3. Rome: New Lifestyles for a More Sustainable City

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Three Case Studies in Rome

- The investigation on the Appia Antica Park is part of a national research on archaeological areas in metropolitan contexts, and has matured through on-site visits and data collection, archival research, public conferences, design workshops, students’ thesis, theory seminars, and work sessions to produce interpretative maps. The research was developed in parallel, following the same research methodology in two other case studies: the University of Napoli progressed on the archeological area of Campi Flegrei, and the University of Siracusa on Piazza Armerina [30]. The results of these investigations are compiled in four books [8,31,32,33].

- The study on Rome’s city walls [34] is ongoing. The research team is operating in thematic groups. Dialogue and interaction are provided through theoretical seminars and design workshops actively involving significant actors (administrators, citizens’ associations, foundations) towards concrete prospects of social, economic and administrative feasibility. The research will be compiled in a publication titled “The Walls of Rome. An ecological and cultural infrastructure for the contemporary city”.

- The research on the ArchaeoGRAB [35] is starting, and so far, has produced a design workshop and preliminary study seminars. An exhibition at the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Moderna in Rome and publications are under development.

- The Appian Way Park

- b.

- Rome’s City Walls

- c.

- The ArchaeoGRAB

2.2. Methodologies

- Retrieving and recomposing the fragmented territory.

- cartographies (historical, updated, ecological networks, land covers, uses, etc.);

- historical images;

- photographic campaign to explore the current image of the territory;

- survey of criticalities and potentials of the area examined;

- interviews to understand collective needs, lifestyles;

- systematization of the collected data on a georeferenced basis.

- b.

- Documentation Regarding Existing National and International Integrated Programs and Pilot Projects (Healthy Corridors, Slow Mobility and Heritage).

- on healthy corridors, green mobility and regeneration of public spaces;

- on tactical urbanism, flexible interventions on public space;

- on cultural itineraries and eco-tourism;

- on the «post-COVID-19 city»;

- on the reuse of existing buildings.

- c.

- Analyzing the urban dynamics that can be triggered by the rehabilitation and integration of infrastructural systems.

- thematic studies to understand current and future social dynamics;

- identification of alternative strategies.

- d.

- Selection of specific areas and goals to implement pilot projects.

- meetings with heritage superintendencies, archaeological sites, municipalities, environmental organizations, transportation bodies;

- meetings involving local communities and associations operating in the area to discuss strategic objectives;

- detection of the interventions and their capacity to build thematic networks;

- elaboration of interpretative maps and schemes;

- synthesis of data collected to develop design ideas.

3. From the Road to the “Superpark”: A Project for the Appian Way

3.1. Historical Elements

3.2. The Appia Antica Park as a Park of the 21st Century

- The Points (The Hotspots)

- The Lines (The Sustainable Mobility)

- The Surfaces (The Park Landscapes)

4. Discussion

- Archaeological parks are usually enclosed areas separated from the city fabric although their ruins belong to the palimpsest of the city. What role do we want to give to this specific form of the past nowadays, especially in more peripherical areas?

- 2.

- What kind of infrastructure does the city of the twenty-first century need?

- 3.

- What actions and strategies do we need in Rome today?

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Capuano, A. Habitat romano: La periferia sud. In Roma Città Mediterranea. Continuità e Discontinuità Nella Storia; Terranova, A., Capuano, A., Criconia, A., Feo, A., Toppetti, F., Eds.; Gangemi Editore: Roma, Italy, 2007; pp. 72–95. [Google Scholar]

- Banham, R. Los Angeles. The Architecture of Four Ecologies; Harper & Row Publishers: Austin, TX, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, P. Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics; Williams & Norgate: London, UK, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, L.; Eulenstein, F.; Mirschel, W.; Antrop, M.; Jones, M.; McKenzie, B.M.; Dronin, N.M.; Kazakov, L.K.; Kravchenko, V.V.; Khoroshev, A.V.; et al. Landscapes, Their Exploration and Utilisation: Status and Trends of Landscape Research. In Current Trends in Landscape Research. Innovations in Landscape Research; Mueller, L., Eulenstein, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M.; Van Eetvelde, V. Landscape Perspectives. The Holistic Nature of Landscape; Landscape Series 23; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, J. Cultural Memory and Early Civilization. Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination; Cambridge University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; (originally published in 2007). [Google Scholar]

- Capuano, A. Paesaggi di Rovine Paesaggi Rovinati; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, S.; Clauss, L.R.; McGuire, R.H.; Welch, J.R. Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reher, G. Heritage as Action Research. Sustainability 2022, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, K.; Ugolini, A.; Canuti, G. A methodology to evaluate outdoor microclimate of the archaeological site: A case study of the Roman Villa in Russi (Italy). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 35, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletto, G.; Ladu, M.; Milesi, A.; Borruso, G. A Methodological Approach on Disused Public Properties in the 15-Minute City Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadi, M.; Biraghi, C.; Zadeh, M.; Brioschi, L. Urban Porosity. A morphological Key Category for the optimization of the CAS’s environmental and energy performance. J. Eng. Technol. 2017, 4, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celesti-Grapow, L.; Ricotta, C. Plant invasion as an emerging challenge for the conservation of heritage sites: The spread of ornamental trees on ancient monuments in Rome, Italy. Biol. Invasions 2021, 23, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, C.; Grapow, L.; Avena, G.; Blasi, C. Topological analysis of the spatial distribution of plant species richness across the city of Roma (Italy) with the chelone approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 57, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchese, F.; Pignatti, E. La vegetazione nelle aree archeologiche di Roma e della Campagna Romana. Quad. Bot. Ambient. Appl. 2009, 20, 3–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.J. In Search of the Place-Identity Dividend: Using Heritage Landscapes to Create Place Identity, Sense of Place, Health and Quality of Life; pp. 185–199. Available online: http://www.muf.co.uk/ahorsestale/2008 (accessed on 13 December 2013).

- Canto Moniz, G.; Ferreira, I. Healthy Corridors for Inclusive Urban Regeneration. Rass. Archit. Urban. 2019, 158, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.J.; Graham, B.J.; Tunbridge, J.E. Pluralizing Pasts: Heritage, Identity and Place in Multicultural Societies; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Toward a Green Infrastructure for Europe. Developing new concepts for Integration of Nature 2000 into the Wider Countryside. 2010. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/ecosystems/docs/green_infrastructure_integration.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Da Capo Press Books: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lasch, C. La Conversazione e le Arti Civiche. In La Ribellione delle Élite; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Encore Heureux; Delon, N.; Choppin, J.; Eymard, S. Infinite Places. Constructing Buildings or Places? Editions B42: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci. Paesaggio, Ambiente, Architettura, Documenti di Architettura; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- One Health Initiative Task Force (OHITF), 2021. One Health Commission. Available online: https://www.onehealthcommission.org/en/why_one_health/what_is_one_health/ (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Schoonderbeek, M. Theory of “Design by Research”; Mapping Experimentation in Architecture and Architectural Design. Ardeth 2017, 1, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the European Cultural Heritage Strategy for the 21st century (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 22 February 2017 at the 1278th Meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies). Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806f6a03 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Nieto, M.J.T.; Roura, F.I.; Garcia, J.M.R.; Puentes, E.R. The Galician Archaeological Heritage Network. In Landscapes as Cultural Heritage in the European Research, Proceedings of the Open Workshop, Madrid, Spain, 29 October 2004; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas: Madrid, Spain, 2006; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society; Council of Europe Treaty Series—No. 199; Council of Europe: Faro, Portugal, 2005; 9p, Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- PRIN 2009, Paesaggi dell’Archeologia, Regioni e Città Metropolitane. Strategie del Progetto Urbano Contemporaneo per la Tutela e la Trasformazione. Available online: https://prin.mur.gov.it/Ricerca?Filtro.Anno=%25&Filtro.Ateneo=Universit%C3%A0+degli+Studi+di+ROMA+%22La+Sapienza%22&Filtro.Argomento=&Filtro.Cognome=CAPUANO (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Capuano, A.; Carpenzano, O.; Toppetti, F. Il Parco e la Città. Il Territorio dell’Appia nel Futuro di Roma; Quodlibet: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- Capuano, A.; Toppetti, F. Roma e l’Appia. Rovine Utopia Progetto; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miano, P.; Izzo, F.; Pagano, L. I Campi Flegrei. L’Architettura per i Paesaggi Archeologici; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza University Research Grants 2018/Large Projects: Roman Infrastructure. The Urban Walls and the Central Archaeological Area in New Vital Cycles of Cultural Promotion, Technological Innovation, Socioecological Reactivation and New Competitiveness for the City of Rome. Available online: https://web.uniroma1.it/dip_diap/dipdiap/ricerca/ricerche (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Sapienza University Research Grants 2020/Large Projects: ARCHAEOGRAB. Green Network for Sustainable Mobility and Public Space Projects for the Enhancement of Archaeological and Natural Heritage in the Suburbs of the City of Rome. Available online: https://bandiricerca.uniroma1.it/sigeba/#/proposte/2235823/view (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Resolution of the Capitoline Junta, n. 143 July 17, 2020, Approvazione dello Schema di Assetto Generale dell’Anello Verde, a Valere Quale Atto-Strumento di Indirizzo Programmatico per la Riqualificazione Sostenibile dell’Anello Ferroviario e del Settore Orientale del Territorio di Roma Capitale. Available online: https://www.urbanistica.comune.roma.it/anello-verde.html (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- DM 44 23/01/2016 Reorganization of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities. 2016. Available online: http://www.regioni.it/news/2016/03/14/d-m-23-01-2016-riorganizzazione-ministero-beni-culturali-e-turismo-448487/ (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- DM 198 09/04/2016 Dispositions Regarding Archaeological Areas and Parks and Institutes and Places of Culture of Relevant National Interest Pursuant to Article 6 of Ministerial Decree 23 January 2016. Available online: http://pompeiisites.org/wp-content/uploads/Decreto-ministeriale-9-aprile-2016-n.-198-1.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Nicolini, R. Il paradosso del Parco dell’Appia. In Il Parco e la Città. Il Territorio Storico dell’Appia nel Futuro di Roma; Capuano, A., Carpenzano, O., Toppetti, F., Eds.; Quodlibet: Rome, Italy, 2014; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- National Conference “I Territori dell’Architettura”, 31 May–1 June 2019. Available online: https://www.unica.it/unica/it/news_notizie_s1.page?contentId=NTZ172929 (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Pavia, R. Questo Parco s’ha da Fare, Oggi Più che Mai. Commento al libro di Alessandra Capuano e Fabrizio Toppetti; (Città Bene Comune); Casa della Cultura: Milan, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.casadellacultura.it/887/questo-parco-s-ha-da-fare-oggi-piu-che-mai (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Latini, L.; Matteini, T. Manuale di Coltivazione Pratica e Poetica. Per la Cura dei Luoghi Storici e Archeologici nel Mediterraneo; Il Poligrafo: Padova, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Capuano, A. Living Amidst the Ruins in Rome: Archaeological Sites as Hubs for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063180

Capuano A. Living Amidst the Ruins in Rome: Archaeological Sites as Hubs for Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063180

Chicago/Turabian StyleCapuano, Alessandra. 2022. "Living Amidst the Ruins in Rome: Archaeological Sites as Hubs for Sustainable Development" Sustainability 14, no. 6: 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063180

APA StyleCapuano, A. (2022). Living Amidst the Ruins in Rome: Archaeological Sites as Hubs for Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 14(6), 3180. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14063180