“Pop-Up Systems”—Innovative Sport and Exercise-Oriented Offerings for Promoting Physical Activity in All-Day Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. “Sport in the School Environment”, a School Development in Urban Switzerland

- How are these unsupervised PA and exercise-oriented extended opportunities used by different groups of children and adolescents (age-specific and with regard to gender and migration background) at all-day schools?

- How does the use of the free pop-ups relate to supervised PA and exercise-oriented opportunities?

Pop-Up Facilities—An Innovative Idea for PA Promotion

3. Methods

3.1. Exploratory Sequential Case Study 1, Single Pop-Up (Parkour)

3.1.1. Qualitative Instruments

3.1.2. Quantitative Instruments

3.2. Convergent Case Study 2, All Pop-Ups

3.2.1. Qualitative Instruments

3.2.2. Quantitative Instruments

3.3. Data Analyses

3.3.1. Case Study 1

3.3.2. Case Study 2

4. Results on Case Study 1: Parkour

4.1. Semi-Structured Observations of a “Parkour” Pop-Up at a Secondary School

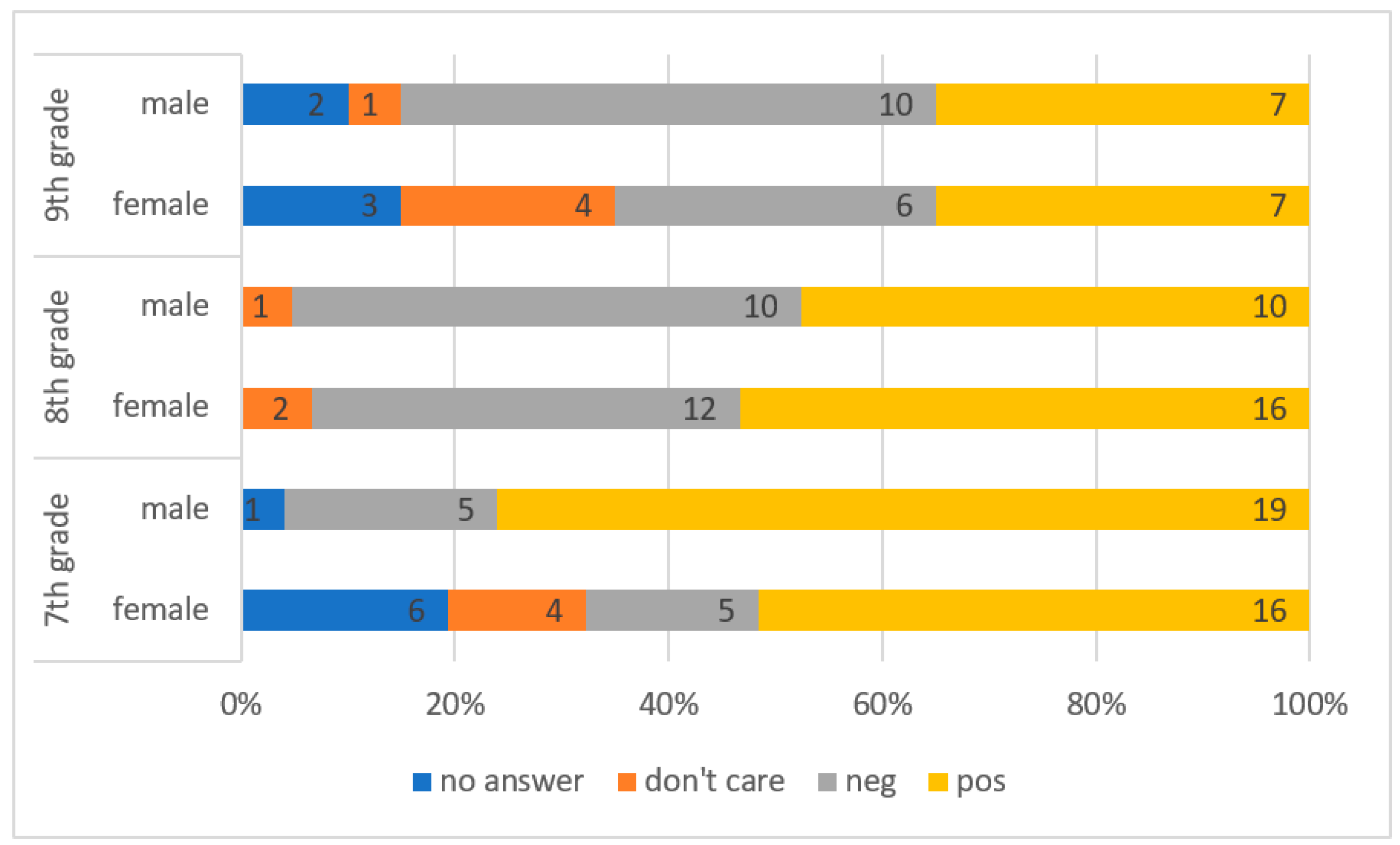

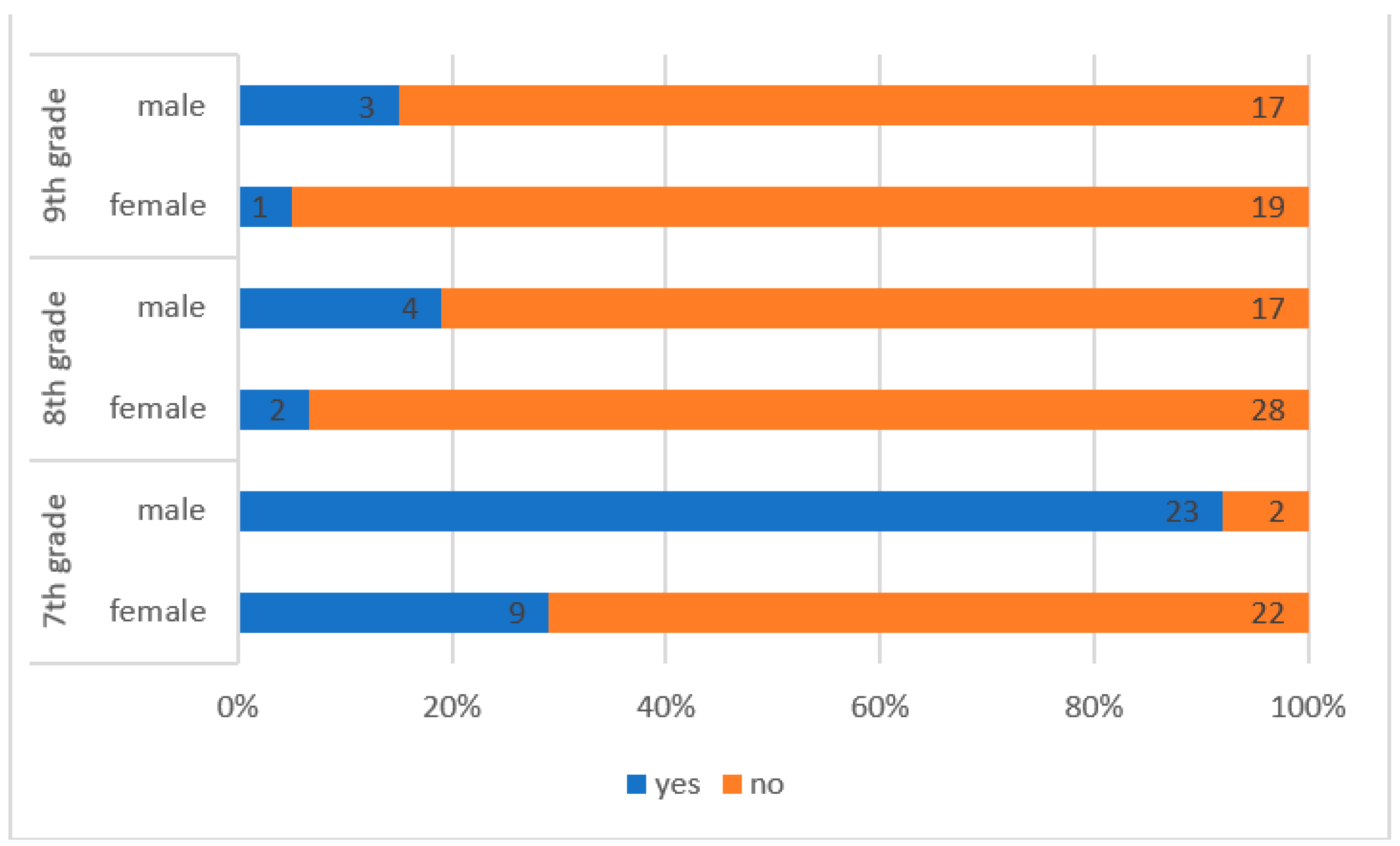

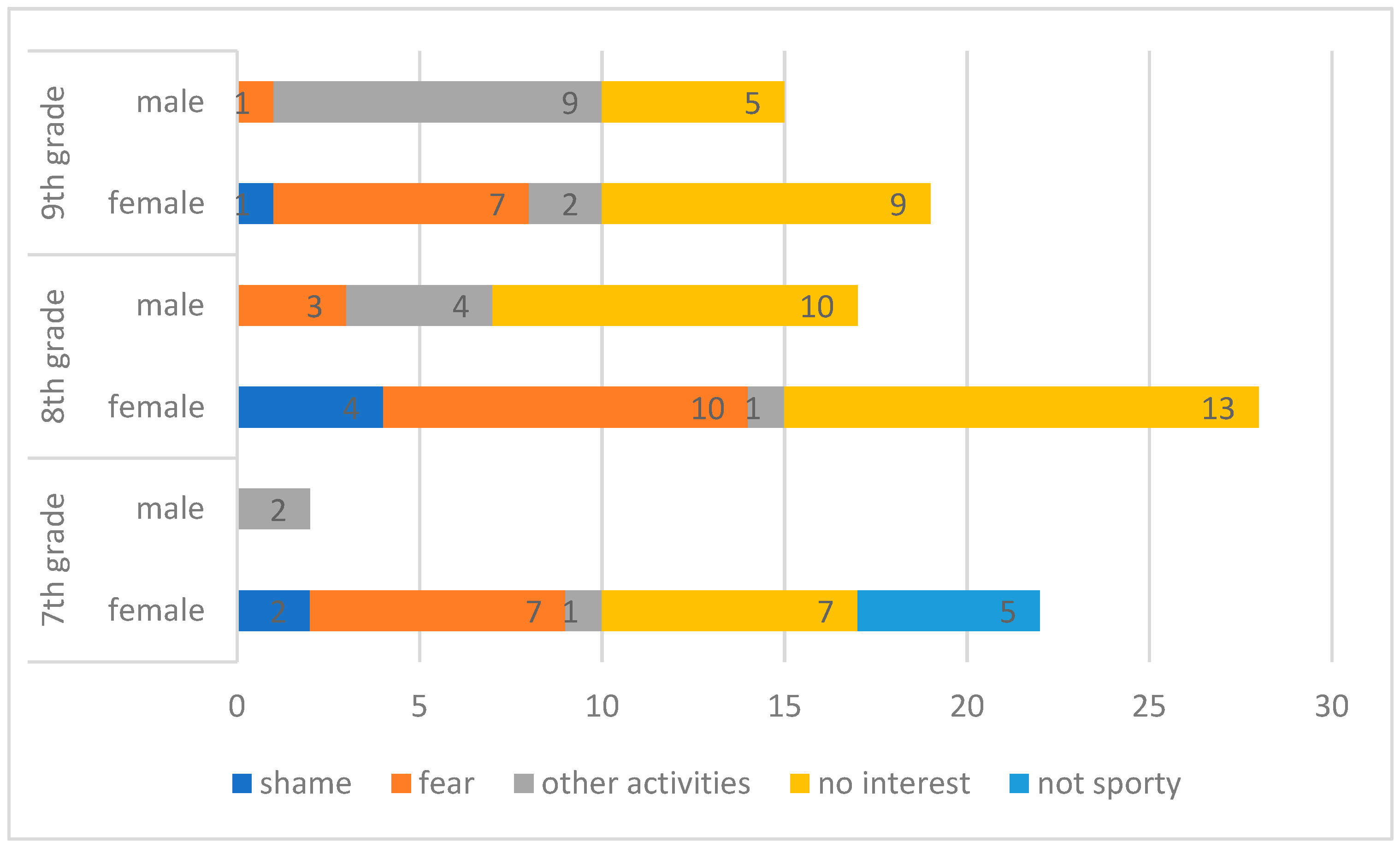

4.2. Quantitative Survey of Students in Secondary School (Grades 7–9)

5. Results of Case Study 2

5.1. Semi-Structured Interviews Conducted with the School Principals and Heads of Student Care on Usage and Perceived Effects of All Pop-Ups

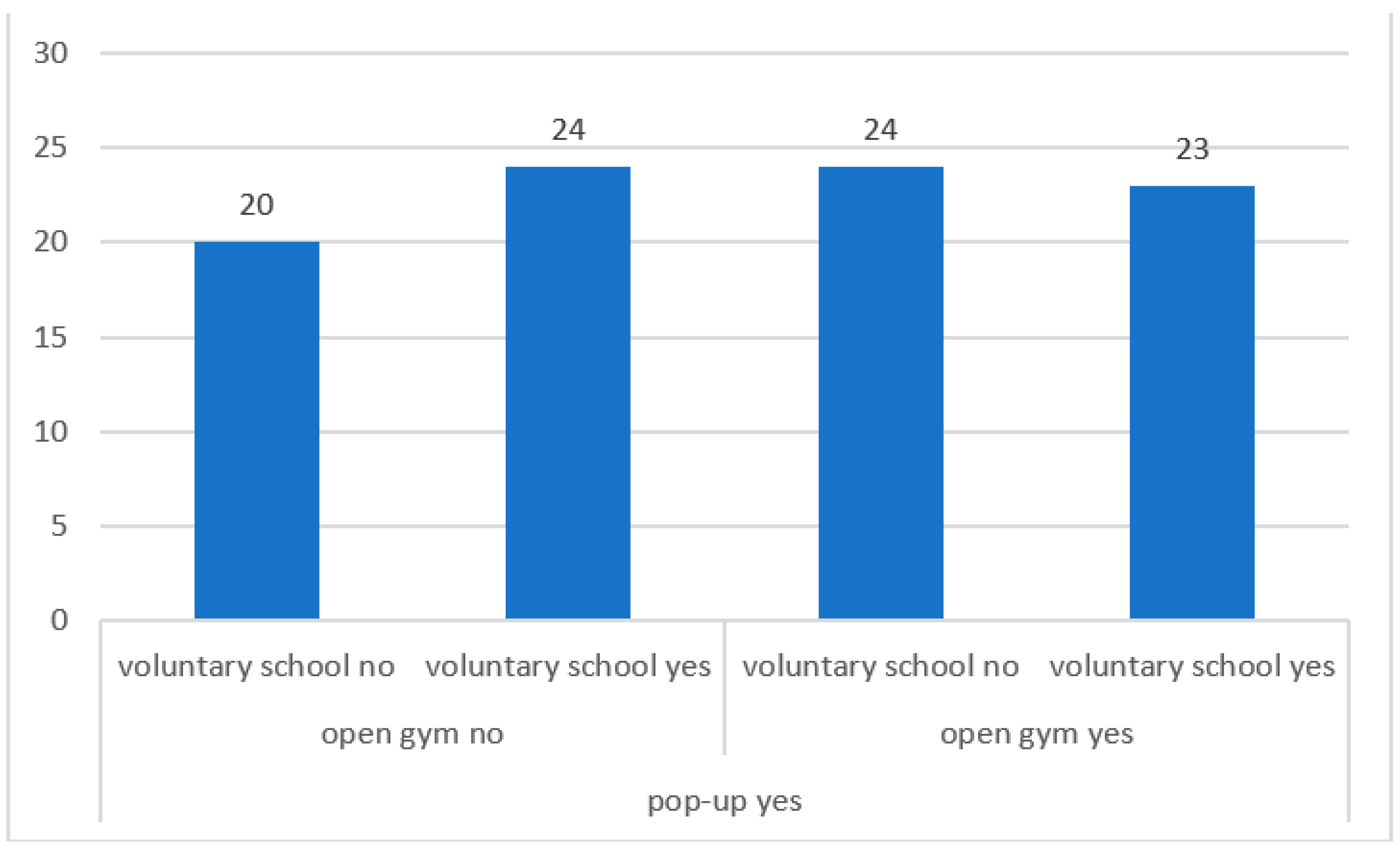

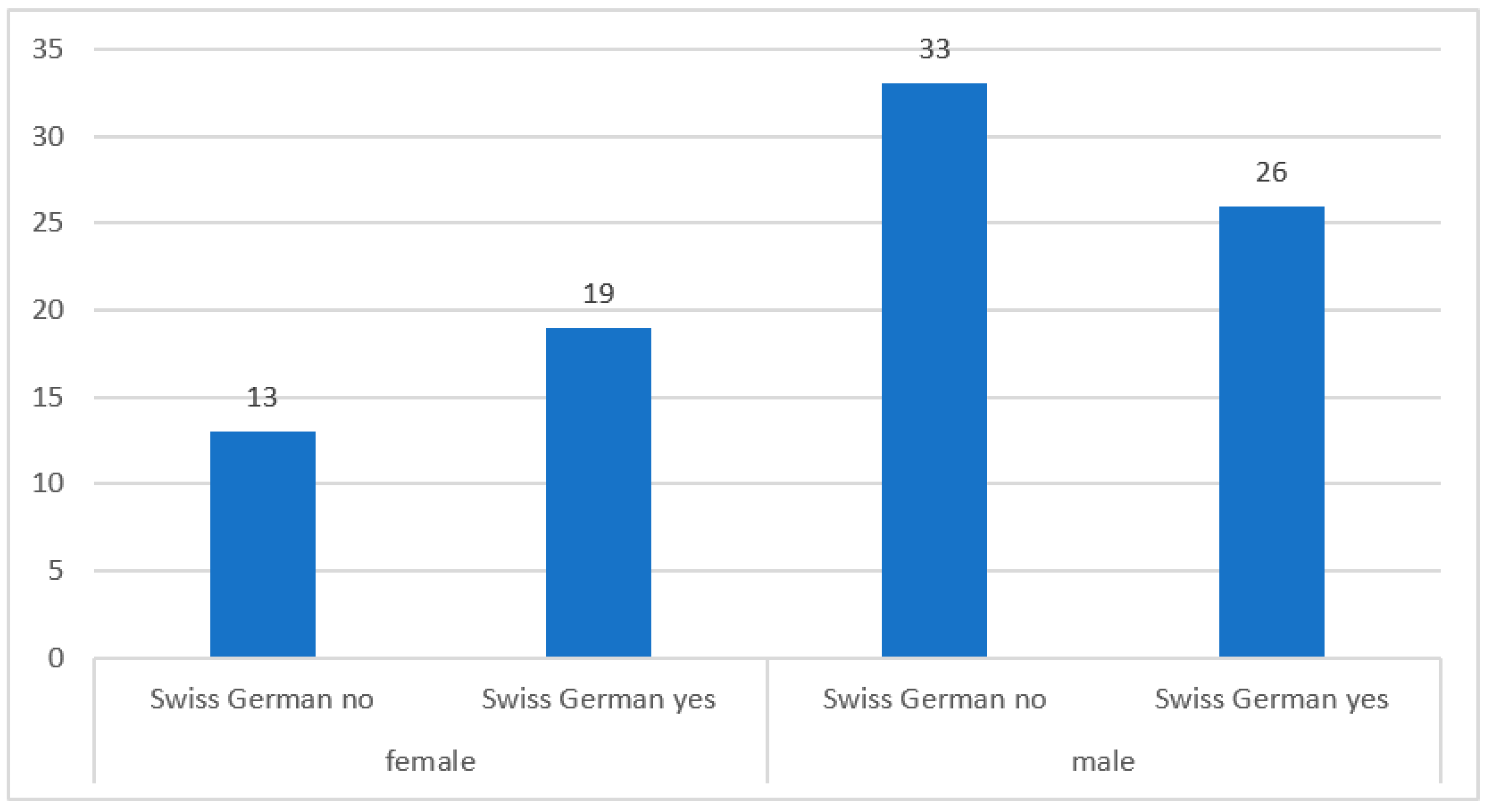

5.2. Quantitative Survey of Second-Grade Students

6. Discussion

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuhn, H.P.; Fischer, N.; Schoreit, E. Soziales Lernen von Jungen und Mädchen in der Ganztagsschule. Zur Bedeutung der Mitbestimmung in den Angeboten für die Entwicklung der schulbezogenen sozialen Verantwortungsübernahme. In Was Sind Gute Schulen? Teil 4: Theorie, Praxis und Forschung zur Qualität von Ganztagsschulen; Fischer, N., Kuhn, H.P., Tillack, C., Eds.; Prolog-Verlag: Immenhausen bei Kassel, Germany, 2016; pp. 148–167. ISBN 9783934575912. [Google Scholar]

- Rauschenbach, T. Ganztagsschule–ein Projekt ohne Konzept. In Bildung über den Ganzen Tag. Forschungs- und Theorieperspektiven der Erziehungswissenschaft; Hascher, T., Idel, T.-S., Reh, S., Thole, W., Tillmann, K.-J., Eds.; Barbara Budrich: Opladen, Germany; Berlin, Germany; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Laging, R. Bewegung und Sport. In Handbuch Ganztagsbildung; Bollweg, P., Buchna, J., Coelen, T., Otto, H.-U., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 437–451. ISBN 978-3-658-23229-0. [Google Scholar]

- Neuber, N. Fachdidaktische Konzepte Sport: Zielgruppen und Voraussetzungen; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; ISBN 978-3-658-28463-3. [Google Scholar]

- Züchner, I. Kooperation von Schulsport und Sportverein: Entwicklungspotential für außerunterrichtliche Sportangebote in Ganztagsschulen. Sportunterricht 2014, 63, 374–379. [Google Scholar]

- Neuber, N. Zwischen Betreuung und Bildung–Bewegung, Spiel und Sport in der Offenen Ganztagsschule. Sportunterricht 2008, 57, 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Holtappels, H.G.; Serwe, E. Bewegung und Sport-ein Förderbereich in Ganztagsschulen? In Jahrbuch Ganztagsschule 2010, Vielseitig Fördern; Appel, S., Ludwig, H., Rother, U., Eds.; Wochenschau: Schwalbach, Germany, 2010; pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Netzwerk Gesundheit und Bewegung Schweiz. Gesundheitswirksame Bewegung bei Kidnern und Jugendlichen–Empfehlungen für die Schweiz; Bundesamt für Sport BASPO: Magglingen, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht, M.; Fischer, A.; Wiegand, D.; Stamm, H. Sport Schweiz 2014. Kinder- und Jugendbericht; Bundesamt für Sport (BASPO): Magglingen, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harring, M.; Peitz, J. Freizeit im Kontext von Ganztagsbildung. In Handbuch Ganztagsbildung; Bollweg, P., Buchna, J., Coelen, T., Otto, H.-U., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 795–809. ISBN 978-3-658-23229-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kamski, I. Mitagessen und Schulhof. In Grundbegriffe Ganztagsbildung: Das Handbuch, 1st ed.; Coelen, T., Otto, H.-U., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 566–575. ISBN 9783531153674. [Google Scholar]

- Hünersdorf, B. Spiel-Plätze. In Handbuch Ganztagsbildung; Bollweg, P., Buchna, J., Coelen, T., Otto, H.-U., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; pp. 823–834. ISBN 978-3-658-23229-0. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, M. Soziale Determinanten der Gesundheit im Spannungsfeld zwischen Ungleichheit und jugendlichen Lebenswelten: Der WHO-Jugendgesundheitssurvey. In Gesundheit, Ungleichheit und Jugendliche Lebenswelten. Ergebnisse der Zweiten Internationalen Vergleichsstudie im Auftrag der Weltgesundheitsorganisation WHO; Richter, M., Hurrelmann, K., Klocke, A., Melzer, W., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Eds.; Juventa: Weinheim, Germany; München, Germany, 2008; pp. 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Greier, K.; Riechelmann, H. Effects of migration background on weight status and motor performance of preschool children. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2014, 126, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haut, J.; Emrich, E. Sport für alle, Sport für manche. Sportwiss 2011, 41, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W. (Ed.) Sozialstrukturelle Ungleichheiten in Gesundheit und Sport–Chancen des Sports; Hofmann: Schorndorf, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zerle, C. Lernort Freizeit: Die Aktivitäten von Kindern zwischen 5 und 13 Jahren. In Kinderleben–Individuelle Entwicklungen in Sozialen Kontexten; Alt, C., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008; pp. 345–366. ISBN 978-3-531-16165-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert, T.; Mensink, G.B.M.; Romahn, N.; Woll, A. Körperlich-sportliche Aktivität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 2007, 50, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Helmke, A. Unterrichtsqualität und Lehrerprofessionalität. In Diagnose, Evaluation und Verbesserung des Unterrichts, 7th ed.; Klett-Kallmeyer: Seelze, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Reusser, K.; Pauli, C. Unterrichtsgestaltung und Unterrichtsqualität-Einleitung und Überblick. In Unterrichtsgestaltung und Unterrichtsqualität-Ergebnisse Einer Internationalen und Schweizerischen Videostudie zum Mathematikunterricht; Reusser, K., Pauli, C., Waldis, M., Eds.; Waxmann: Münster, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Bustamante, R.M.; Nelson, J.A. Mixed Research as a Tool for Developing Quantitative Instruments. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2010, 4, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rast, M. Innovative Sport- und Bewegungsorientierte Angebote in der Tagesschule: Mobile Parkouranlage; Unveröffentlichte Masterarbeit, PH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Quellenberg, H. Studie zur Entwicklung von Ganztagsschulen (StEG). Ausgewählte Hintergrundvariablen, Skalen und Indices der ersten Erhebungswelle. In Zusammenarbeit mit dem StEG-Konsortium und den Mitarbeiter/Innen des StEG-Teams; DIPF u.a: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bader, D.; Fibbi, R. Kinder mit Migrationshintergrund: Ein Grosses Potenzial. Studie im Auftrag der Kommission Bildung und Migration der Schweizerischen Konferenz der Kantonalen Erziehungsdirektoren (EDK). 2012. Available online: http://www.unine.ch/files/live/sites/sfm/files/projets%20de%20recherche/secondo_pot/Bericht_EDK_2012_d.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Ferrari, I.; Schuler, P.; Bretz, K.; Niederberger, L. Sport im Lebensraum Schule (SLS)-Dokumentation der Items und Skalen der Itemsbefragung 2021; Pädagogische Hochschule Zürich: Zürich, Switzerlend, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P.; Fenzl, T. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. In Handbuch Methoden der Empirischen Sozialforschung; Baur, N., Blasius, J., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weltgesundheitsorganisation. Präambel zur Satzung; WHO: Genf, Switzerland, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Bringolf-Isler, B.; Probst-Hensch, N.; Kayser, B.; Suggs, S. Schlussbericht zur SOPHYAStudie; Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute: Basel, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, R.; Jago, R.; Fox, K.R.; Thompson, J.L.; Cartwright, K.; Page, A.S. “Get off the sofa and go and play”: Family and socioeconomic influences on the physical activity of 10–11 year old children. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gramesbacher, E.; Weigelt-Schlesinger, Y. Was interessiert Mädchen in der Schweiz an Sportvereinen? Befunde der Aufsatzstudie aus dem Projekt Girls in Sport. In Stand und Perspektiven der Sportwissenschaftlichen Geschlechterforschung; Frohn, J., Gramesbacher, E., Süssenbach, J., Eds.; Schriften der Deutschen Vereinigung für Sportwissenschaften, Bd.279: Czwalina, Germany, 2019; pp. 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst-Cachay, C. Mädchen und Frauen mit Migrationshintergrund im Organisierten Sport. Ergebnisse zur Sportsozialisation–Analyse Ausgewählter Maßnahmen zur Integration im Sport; Schneider Verlag: Hohengehren, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bahlke, S.; Kleindienst-Cachay, C. Migrantinnen und Migranten im organisierten Sport. In Sport & Gender-(Inter)nationale Sportsoziologische Geschlechterforschung: Theoretische Ansätze, Praktiken und Perspektiven; Sobiech, G., Günter, S., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 139–151. ISBN 978-3-658-13098-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nobis, T.; El-Kayed, N. Social inequality and sport in Germany—A multidimensional and intersectional perspective. Eur. J. Sport Soc. 2019, 16, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, L.K.; Adams, N.; Little, T.D. Self Determination Theory, Identity Development, and Adolescence. In Development of Self-Determination through the Life-Course; Wehmeyer, M.L., Shogren, K.A., Little, T.D., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Qualitative Study | Quantitative Study |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory sequential case study 1 on “Parkour” in fall 2019 | Non-participatory, semi-structured observations of the use of a “Parkour” at a secondary school (grades 7–9) in the city of Zurich in fall 2019, one month, all weekdays, including two weekends | A survey of the students of a secondary school (grades 7–9), (N = 147) about the use of a “Parkour” facility and its justification on the basis of a partially standardized questionnaire |

| Convergent case study 2 on all pop-ups in summer 2021 | Semi-structured group interviews with the school principals and heads of student care (N = 14) on the use of the pop-ups and their perceived effect | A survey of all students of the second primary level (N = 340) on the use of the pop-up facilities using a standardized questionnaire |

| Total | Girls | Boys | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7th grade | 56 | 31 | 25 |

| 8th grade | 51 | 30 | 21 |

| 9th grade | 40 | 20 | 20 |

| Total students | 147 | 81 | 66 |

| Age | Language Swiss German | Other Languages | Bedrooms per Person | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M ± SD | n (%) | n (%) | M ± SD | |

| Total | 407 (100) | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 226 (55.5) | 217 (53.3) | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| Boys | 226 (55.5) | 8.0 ± 0.4 | 113 (27.8) | 129 (31.7) | 0.8 ± 0.4 |

| Girls | 175 (43.0) | 8.1 ± 0.5 | 108 (26.5) | 85 (20.9) | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| Other/diverse | 1 (0.2) | 8.0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 0.7 |

| Voluntary school sports | 170 (41.8) | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 84 (20.6) | 102 (25.1) | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| Unaccompanied offerings | 263 (64.6) | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 143 (35.1) | 148 (36.4) | 0.8 ± 0.5 |

| Supervised Offerings | Unsupervised Offerings | Open Gym | Pop-Ups (N = 340) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%; % rel) | |

| Total | 170 (41.8) | 263 (64.6) | 152 (37.3) | 91 (22.4; 26.8) |

| Male | 114 (28.0) | 158 (38.8) | 100 (24.6) | 58 (14.3; 17.1) |

| Female | 55 (13.5) | 100 (24.6) | 49 (12.0) | 31 (7.6; 9.1) |

| Diverse | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferrari, I.; Schuler, P.; Bretz, K.; Bär, J.; Rast, M.; Niederberger, L. “Pop-Up Systems”—Innovative Sport and Exercise-Oriented Offerings for Promoting Physical Activity in All-Day Schools. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053090

Ferrari I, Schuler P, Bretz K, Bär J, Rast M, Niederberger L. “Pop-Up Systems”—Innovative Sport and Exercise-Oriented Offerings for Promoting Physical Activity in All-Day Schools. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053090

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerrari, Ilaria, Patricia Schuler, Kathrin Bretz, Jessica Bär, Marianne Rast, and Lukas Niederberger. 2022. "“Pop-Up Systems”—Innovative Sport and Exercise-Oriented Offerings for Promoting Physical Activity in All-Day Schools" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053090

APA StyleFerrari, I., Schuler, P., Bretz, K., Bär, J., Rast, M., & Niederberger, L. (2022). “Pop-Up Systems”—Innovative Sport and Exercise-Oriented Offerings for Promoting Physical Activity in All-Day Schools. Sustainability, 14(5), 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053090