Quality Assurance in E-Learning: A Proposal from Accessibility to Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

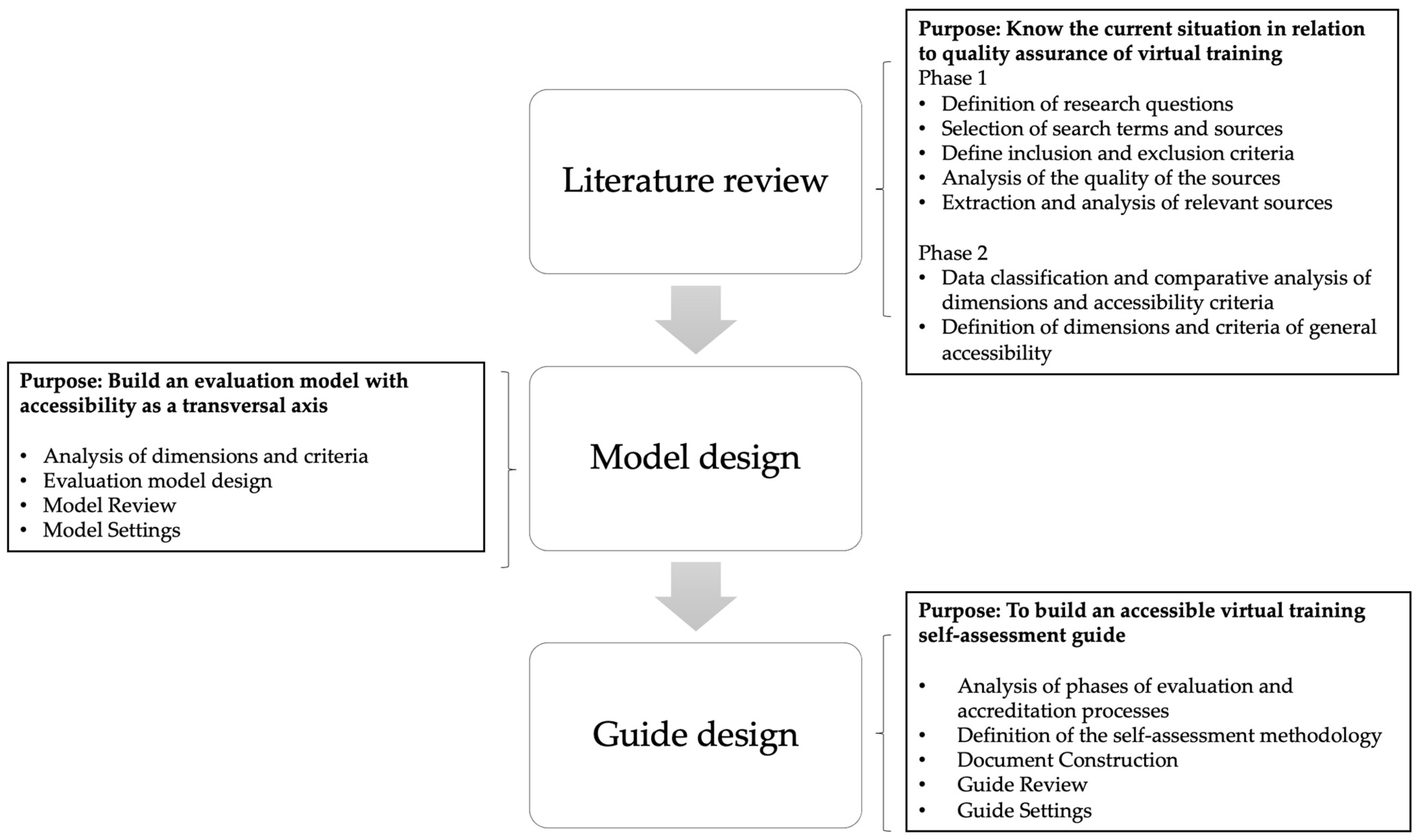

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

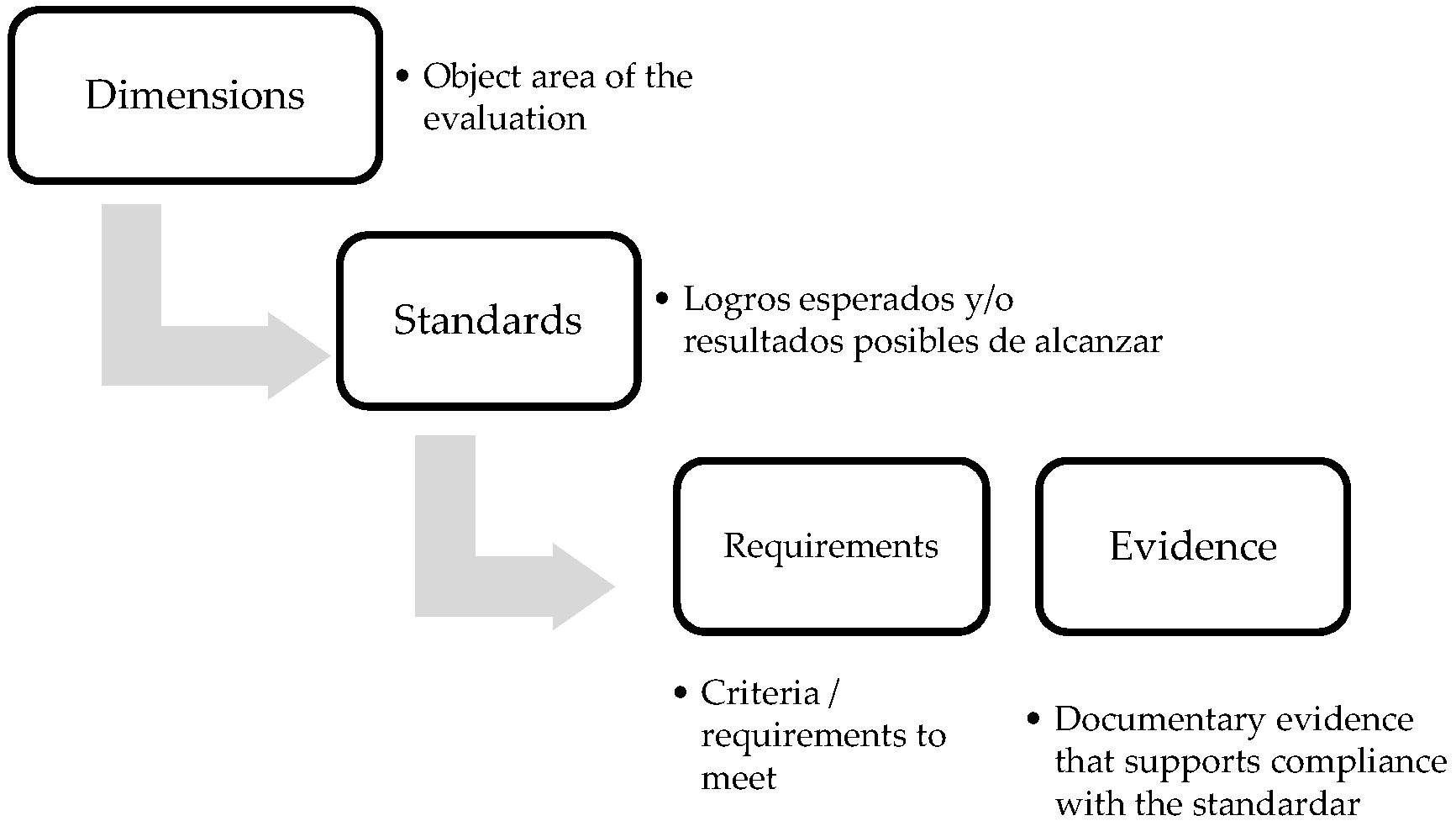

2.2. Model Design

2.3. Design of the Guide

3. Results

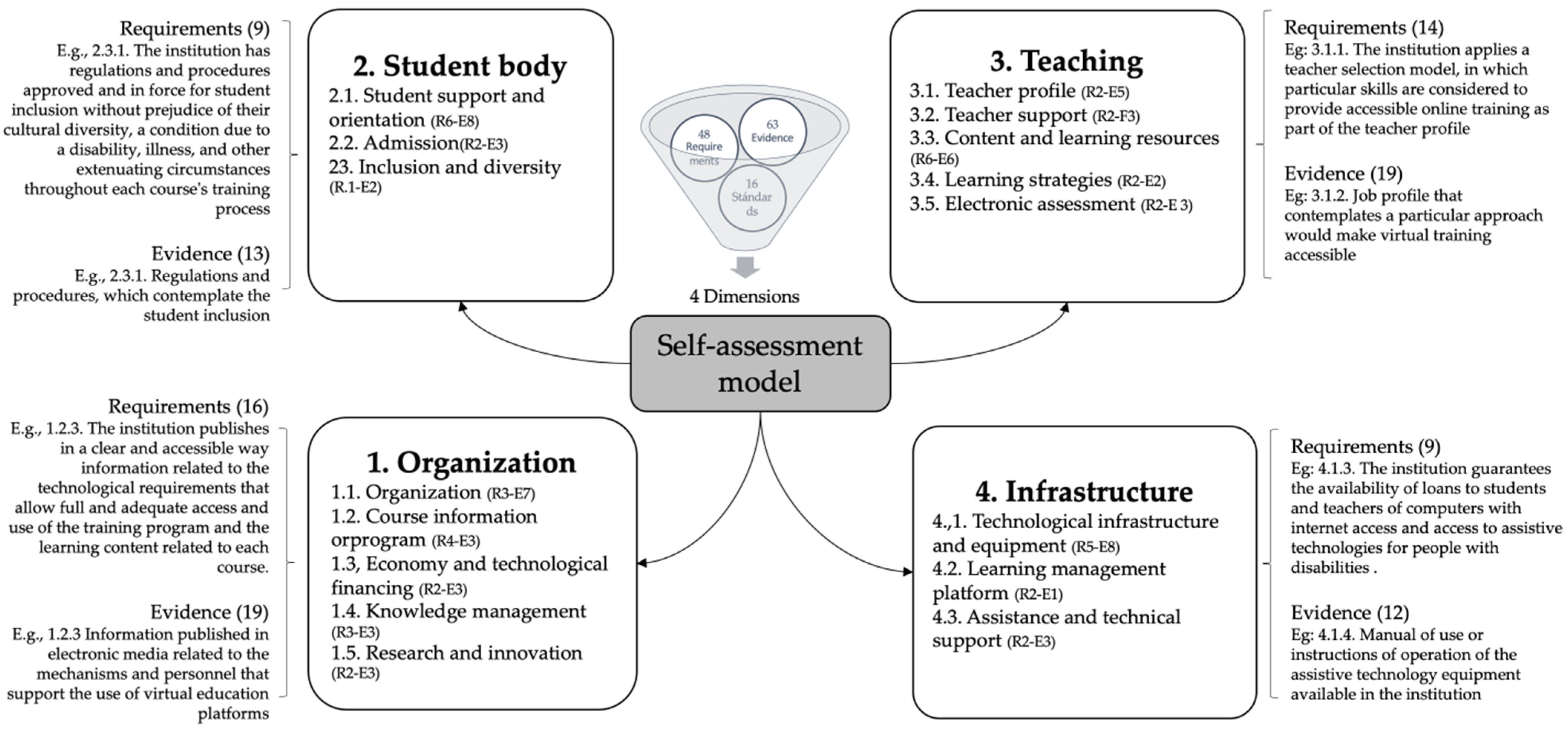

3.1. Self-Assessment Model

- ▪

- Organization: evaluation of the institution’s organization and general strategic actions that support the training process and permanent quality assurance that it must pursue.

- ▪

- Students: evaluation of the actions that the institution promotes and applies for the benefit of students as training recipients.

- ▪

- Teaching: evaluation of the actual virtual education process resulting from the construction of knowledge, educational innovation, and skills and abilities in the chair itself.

- ▪

- Infrastructure: evaluation of the technological and technical support structure that enables the teaching–learning process.

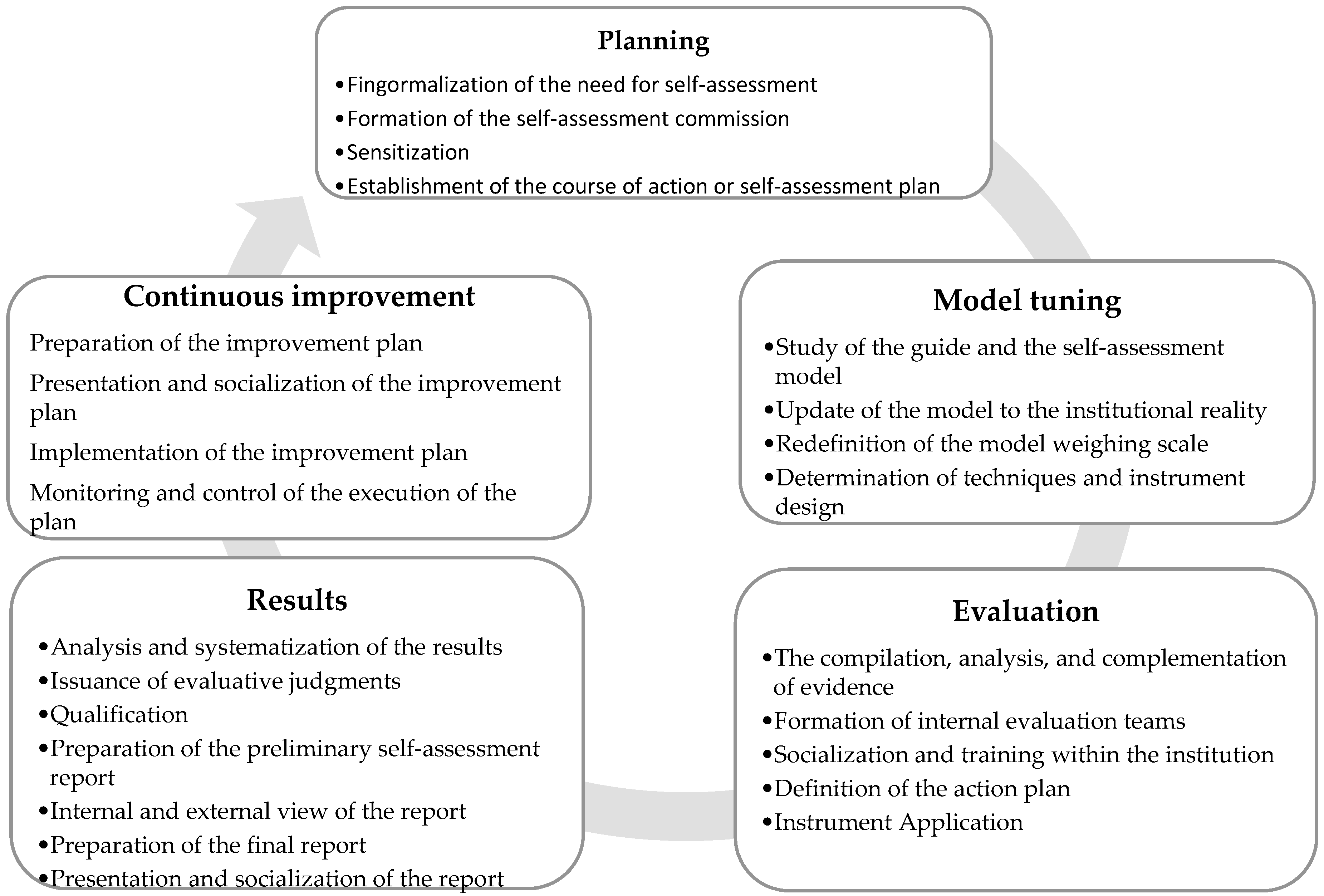

3.2. Implementation Methodology

- Planning: This phase begins with the formalization of the need for self-assessment by the institution, formalization that, in addition to giving support to the process and its main actors, seeks the involvement and commitment of the members of the institution, being necessary to raise awareness of the process and its purpose. In this phase, the self-assessment team is formed, whose profile would refer to a group of professionals with experience in self-assessment processes and process management. Finally, the work plan is defined concerning the process.

- Model tuning or Refinement of the model: Its objective is to redefine or adjust the model to the institutional reality. An update of the model is sought, with (a) a possible inclusion/exclusion of requirements according to the objectives of the institution and the scope of evaluation (institutional, program, course), (b) inclusion of evidence that supports compliance with the standard and its requirements, (c) review and adjustment of the rating scale (weighting matrix) according to the value that the institution estimates according to the scope of the self-assessment and (d) determination of the assessment techniques to be applied and design instruments (evidence collection sheets, interview guides, etc.).

- Evaluation: Constitutes the evaluation execution based on previously defined techniques and instruments.

- Results: It constitutes the analysis and systematization of the results of the “Assessment” sub-process, which begins with the identification of the strengths and weaknesses of the institution in terms of virtual education and culminates with the preparation of the self-assessment report.

- Continuous improvement: It constitutes the phase aimed at minimizing the gap between the established quality standards and the level of compliance in practice, as well as maintaining the achievements obtained and guaranteeing that there is no evidence of a setback in the standards, also including other actions that enable the growth of the institution.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| MODEL/Author(s)—Year | Characteristics: Level Type Focus | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hadullo, Oboko & Omwenga—2017 [38] | Institutional Conceptual or theoretical Developing countries | Model for evaluating the quality of e-learning systems in developing countries, the result of adapting the Briggs Framework to e-learning based on five existing models |

| Dilan & Fernandez—2015 [37] | Institutional Conceptual or theoretical Developing countries | Conceptual framework of quality of a virtual institution aimed at quality improvement and quality assurance. |

| SQAMELS Farid—2018 [52] | Platform Conceptual or theoretical Developing countries | Sustainable quality assessment model for e-learning systems from a soft-ware perspective. Its focus is on the technological platform that supports the programs, excluding sections such as pedagogical, personal, institutional, cultural, and social |

| TeSLA Huertas—2017 [57] | e-assessment Conceptual or theoretical European Union | A conceptual framework for an internal quality assurance system for e-assessment, in the context of higher education and e-learning, developed considering the standards and guidelines for quality assurance of the European Higher Education Area. |

| Marciniak—2018 [9] | Program Conceptual or theoretical Spain | A comprehensive model for evaluating the quality of online education programs, whose focus is firstly on assessing the quality of the online program itself, and then on the continuous evaluation of the online education program, to improve through feedback and self-adjustment. |

| Mejia-Madrid & Molina Carmona [47] | Institutional Conceptual or theoretical International | Model for evaluating the quality of distance higher education based on information and communication technologies (ICT), whose purpose is to guarantee the proper use of ICT in an institution’s teaching and learning processes, academic processes, and administrative processes. |

| OSCQR—2019 [50] | Course Certification International | Scorecard OSCQR allows course design review, constituted as a tool to improve the quality and accessibility of a course design, part of the OLC quality framework to guarantee the excellence of online learning of higher education institutions. |

| OCL—2011 [58] | Program Certification International | Online Program Management Scorecard aimed to measure the effectiveness of an institution’s online learning programs. Part of OLC’s quality framework to ensure online learning excellence for higher education institutions. |

| FRAMEWORK OF INSTITUTIONAL CONDITIONS FOR ONLINE TEACHING Luna—2018 [48] | Institutional Conceptual or theoretical México | An analytical framework for evaluating the institutional conditions of online teaching in higher education. |

| Torres-Barzabal—2019 [27] | Teaching Conceptual or theoretical European Union | Qualitative evaluation model of quality of online teaching from a pedagogical point of view, for undergraduate and postgraduate programs. The evaluation has two approaches, one related to the content and the information provided in the courses referring to the teaching action and a second approach about the teaching process applied in each class. |

| eMM (e-Learning Maturity Model) Marshall—2010 [49] | Institutional Self-assessment International | A quality framework for e-learning improvement, designed to assess the maturity of an institution to identify the key processes and practices necessary to achieve robust and sustainable improvements in e-learning quality. It can be considered a version of CMM from an educational perspective. |

| E-LEARNING QUALITY Masoumi & Lindstrom—2012 [59] | Course/Program/Institutional Self-assessment Developing countries | A framework to promote and ensure quality in virtual institutions sensitive to specific cultural contexts. |

| CAPEODL Khan—2005 [60] | Program Self-assessment International | Online program evaluation of the model. The model is the integration of the Continuity Model in E-learning P3 (Person as Processes-Products) and the E-learning Framework of Khan (2004) from the seven stages of e-learning (planning, design, production, evaluation, marketing, instruction, and maintenance). |

| ACCESSIBILITY ACCREDITATION MODEL—2013 [28] | Course Certification Latin America and the Caribbean | Accreditation model for accessibility in virtual education of the ESVIAL Project and the Latin American and Caribbean Institute for Quality in Distance Higher Education (CALED), whose objective is to certify the quality and accessibility of virtual courses |

| CALED—2010 [29] | Program Certification Latin America and the Caribbean | Self-assessment model of distance undergraduate programs of the Latin American and Caribbean Institute for Quality in Distance Higher Education (CALED) whose purpose is to contribute to the improvement of quality in the teaching of Distance Higher Education |

| COLOMBIA ACCREDITATION MODEL—2013 [30] | Program Certification Colombia | Official accreditation model of undergraduate, professional technical, and technical training programs for face-to-face and distance learning in Colombia. |

| MEXICO ACCREDITATION MODEL—2018 [31] | Program Accreditation Mexico | A model of evaluation and accreditation of educational programs in higher education institutions with distance or online modalities (2017). CIEES is an accreditation body endorsed by COPAES (Council for the Accreditation of Higher Education in Mexico). |

| ACCREDITATION MODEL OF COSTA RICA—2011 [32] | Program Accreditation Costa Rica | Official model of career accreditation of Costa Rican universities that guarantees that a quality service is provided through self-assessment and external evaluation processes. |

| PDPP Zhang & Cheng—2012 [51] | Course Conceptual or theoretical International | The four-phase evaluation model for e-learning courses includes planning, development, process, and evaluation of products (PDPP). |

| UNIQUe EFQUEL—2011 [41] | Institutional Certification European Union | UNIQUE is a high-quality institutional certification for the exceptional use of ICT in learning and teaching, whose model is subdivided into three evaluation dimensions (learning and institutional context, learning resources, and learning processes). |

| ELQ—2008 [53] | Institutional Conceptual or theoretical European Union | E-Learning quality model for evaluating the quality of e-learning in higher education. |

| Model | Dimensions | Accessibility Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Hadullo, Oboko & Omwenga—2017 [38] | Course Development (D1) Student Support (D2) Evaluation design (D3) Institutional factors (D4) User characteristics (D5) Acting in general (D6) | Ease of use of the platform (A1). Training for students and teaching staff in using the platform and e-learning resources (A2). Internet access and ICT access should be made available to students and teachers (availability for loan) (A3). |

| Dilan & Fernandez—2015 [37] | Knowledge management (D7) Economics and financing (D8) Teacher and staff training (D9) Role of the teacher and the student (D10) | Not evidence. |

| Sqamels Farid—2018 [52] | System Quality (D13) Service quality (D14) Charisma (D15) | The ability of the student to access learning with minimal effort. (A4). Possibility of access to the platform from various locations (rural/urban) prioritizing students with disabilities. (TO 5). |

| TeSLA Huertas—2017 [57] | Policy and strategy for quality assurance in e-assessment (D16). Environment and infrastructure of e-assessment (D17). Course curriculum and assessment resources (D18). Student support (D19). Support for teachers (D20). Learning analysis (D21). Public information (D22). | The course curriculum should reflect the environment and infrastructure of the e-assessment with the possible exam scenarios planned. The evaluation resources must provide teachers and students with different variants to support any learning style, as well as students with special needs (physical, social, mental, etc.). (A6). |

| Marciniak—2018 [9] | Justification of the program (D23). Program objectives (D24). Student profile (D25). Thematic content of the e-learning program (D26). Learning activities (D27). Online teacher profile (D28). Learning manuals (D29). Educational strategies (D30). Tutoring (D31). Assessment of student learning (D32). Virtual platform (D33). Initial evaluation of the program (D34). Process evaluation of the program (D35). Final evaluation of the program (D36). | Appropriate, sufficient, up-to-date, motivating, and accessible learning materials for students. (A7). |

| Mejia-Madrid & Molina Carmona [47] | Technology for learning and knowledge, (D37). Teaching and learning processes enhanced with ICT. (D38). Strategic processes that support distance education. (D39). | Allow for diversity and accessibility of learning resources (A8). Allow flexible learning based on student needs (A9). |

| OSCQR—2019 [50] | Summary and course information (D40). Technology and tools (D41). Design and layout (D42). Content and activities (D43). Interaction (D44). Evaluation and feedback (D45). | Printable syllabus available in PDF and HTML (A11) The course includes links to relevant policies on plagiarism, use of computers, complaints, and disability accommodations (A12). All technological tools comply with accessibility standards (A13). A logical, coherent, and orderly design is established. In addition, the course is easy to navigate (consistent color scheme and icon layout, related content organized together, prominent titles) (A14). There is enough contrast between the text and the background to see the content easily (A15). Text is formatted with headings and other styles to improve readability and document structure (A16). |

| OCL—2011 [58] | Institutional support (D46). Technological support (D47). Development and instructional design of online courses (D48). Structure of online courses (D49). Teaching and learning (D50). Social and student participation (D51). Support for teachers (D52). Student support (D53). Assessment and assessment (D54) | Development and instructional design of online courses: Alternative publishing content (CDs) is available for students who do not have permanent access to the internet or low-speed connections (A17). Alternative assessment systems are available for students who do not have permanent access to the internet (A18). Usability tests are applied to incorporate the recommendations issued or results obtained (A19). Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) are used in content and on the platform (A20). Instructional materials are easily accessible to students and are easy to use (A21). The course provides an adequate response to the needs of students with disabilities through alternative instructional strategies and referral to special institutional resources (A22). The program demonstrates compliance with and review of accessibility standards (A23). Text content is available in an easily accessible format, preferably HTML (A24). All text content is readable by assistive technology, including a PDF or any text contained in an image (A25). |

| Framework of Institutional Conditions for Online Teaching. Luna—2018 [48] | Institutional policy (D55). Institutional organization (D56). Institutional regulations (D57). Institutional plans and programs (D58). Online educational model (D59). Teaching work conditions (D60). Infrastructure and equipment (D61) | The technological infrastructure used in educational spaces for teaching courses (videoconferences, satellite links, internet applications, and others) ensures continuous and uninterrupted access for students and teachers during the course duration (A26). There are special and appropriate facilities for carrying out collective activities mediated by ICT (A27). There are a digital library and library services accessible to all students and teachers, regardless of their geographical location and when they are consulted (A28). A text equivalent is provided for each non-text element (alt tags, subheadings, transcripts, etc.) (A29) |

| Torres-Barzabal—2019 [27] | Course content and information: Identification of the teaching action (D62). Delimitation of the teaching action (D63). Design of teaching action (D64) Learning process: Teaching participation (D65). Feedback (D66). Motivation (D67) Evaluation (D68). | The content must be presented homogeneously concerning color, text, font, distribution of information, logical sequence, etc. (A30). Graphics, images, and videos are displayed in an accessible format (A31). The same content is provided in different formats (HTML, PDF, Word, audio, video, etc.) (A32). |

| E-learning Quality Masoumi & Lindstrom—2012 [59] | Institutional factors (D69) Instructional design factors (D70). Evaluation factors (D71). Technological factors (D72). pedagogical factors. (D73) Student support factors. (D74). Support factors for teachers (D75). | Learning materials must be reasonable and appropriately accessible to students whenever they wish. (A33). Access to learning materials should be granted to students with disabilities (e.g., ’screen readers’ for those with limited vision, ‘text narration’ for those with little or no hearing, etc.) (A34). The e-learning platform must meet adequate bandwidth demands (e.g., materials are accessible without long delays). (A35). The online learning platform should provide students with a user-friendly, evident and predictable environment, considering: (a) developing a user-friendly e-learning environment, (b) cognitive load through proper use of color and design, (c) helping users visually through the appropriate use of text, images, audio, video, animation, graphics, etc., (d) standardized navigation in which users can find their way with a minimum of clicks (A36). In the design and use of e-learning environments, students’ needs, skills, and knowledge must be addressed and supported to meet their individual needs or preferences (A37). Various learning scenarios should be provided to support multiple learning styles and learning abilities (A38). |

| eMM (e-Learning Maturity Model) Marshall—2010 [49] | Learning (D76). Development (D77). Support (D78). Evaluation (D79). Organization (D80). | The courses are designed to help students with disabilities (A39). Courses are designed to support various learning styles and learning abilities (A40) |

| CAPEODL Khan—2005 [60] | Pedagogical (D81). Technological (D82). Interface design (D83). Evaluation (D84). Management (D85). Resource support (D86). Ethical (D87). Institutional (D88). | The platform interface design considers content design, navigation, accessibility, and usability criteria (A41). |

| Esvial Accessibility Accreditation Model—2013 [28] | Technology (D89). Training (D90). Instructional Design (D91). Services and support (D92). | Guarantee access to all recipients, considering (A42):

|

| CALED—2010 [29] | Leadership and management style (D93). Policy and strategy (D94). People development (D95). Resources and alliances (D96). Recipients and educational processes (D97). Results of the recipients and educational processes (D98). People development results (D99). Company results (D100). Overall results (D101). | The student profile is studied, identified students with disabilities and the nature of the disability (auditory, visual, physical) (A44). Consider computer systems the interoperability, compatibility, usability, and objectives of the program (A45) |

| Colombian Accreditation Model—2013 [30] | Mission, vision, and institutional project of the program. (D102). Students. (D103). Teachers. (D104). Academic processes. (D105). Research and artistic and cultural creation. (D106). National and international visibility. (D107). Impact of graduates on the environment. (D108). Institutional welfare. (D109). Organization, administration, and management. (D110). Physical and financial resources. (D111). | No evidence |

| Mexico Accreditation Model—2018 [31] | Purpose of the program (D112). General conditions of the program (D113). Curriculum (D114). Comprehensive training activities (D115). Instructional Design and Course Management (D116). Entry to the program (D117). School career (D118). Exit from the program (D119). Student results (D120). Academic and support staff (D121). Infrastructure (D122). Support Services (D123) |

The platform used by the educational program must offer permanent access alternatives to materials in formats that meet the needs of students (A48). The structure of access to the different tools and services in the courses must allow students to become familiar with the interface in a short time and to carry out their activities without difficulty (A49).

|

| Accreditation Model of Costa RICA—2021 [32] | Relationship with the context (D124). Resources (D125). Educational process (D126) Results (D127). | No evidence |

| PDPP Zhang & Cheng—2012 [51] | Planning (D128). Development (D129). Process (D130). Evaluation (D131). | No evidence |

| UNIQUe EFQUEL—2011 [33] | Learning and institutional context (D132). Learning Resources, (D133). Learning processes (D134). | Institutional accessibility policies (disability) also cover the ICT offers of the institution (A51). The available learning resources have been tested for use and corrected to overcome common technical problems (A52). The course creation and production tools can cover a variety of current formats and thoroughly take into account the principles of usability, accessibility, interoperability, and durability, aimed at facilitating the application in the course (A53). |

| Generalized Dimensions | Related Dimensions | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Assessment and continuous improvement | D6, D34, D35, D36, D54, D95, D70, D71, D79, D84, D98, D99, D100, D101, D107, D108, D127, D131 | It is characterized by the constant evaluation process that can be maintained on the course or program, in which aspects are considered to determine the achievement of objectives, the effectiveness of learning and re-deeming students, evaluation of teaching performance, the sustainability of the course or program, the satisfaction not only of students and teachers but also of society as well as the impact, compliance with rules and regulations, seeking to identify the weaknesses that allow decision-making that permits constant improvement. |

| Technological infrastructure and equipment | D4, D13, D14, D17, D21, D33, D37, D41, D47, D61, D72, D82, D85, D89, D96, D111, D122, D133 | It is characterized by aspects related to the technological infrastructure supporting the virtual education system, the LMS platform (learning manager system), and the equipment made available to users who need it. Infrastructure and equipment are conditioned to be accessible, robust, safe, and, continuous |

| Learning strategies | D10, D30, D38, D44, D50, D59, D65, D66, D73, D76, D81, D91, D105, D116, D126, D129, D132 | It is characterized by the pedagogical aspects that revolve around the development of the course, seen from the teaching–learning methodology, the scenarios and resources used, the interactivity and use of tools/resources for interaction between student and teacher, dedication, and timely feedback by the teacher |

| Content and learning resources | D15, D26, D27, D29, D42, D43, D48, D64, D70, D77, D83, D86, D91, D116, D129 | It is characterized by the adequate design of a course’s contents and learning resources, considering having clearly defined objectives and learning outcomes, learning activities and interaction with the student, complying with usability and accessibility standards |

| Student Support and Guidance | D19, D31, D58, D67, D74, D77, D78, D88, D103, D109, D118, D123, D133. | It is characterized by aspects related to student welfare concerning access to scholarships and financing, guidance and academic advice, tutorials, monitoring of students with attendance irregularities, and other student services. |

| Assistance and technical support | D5, D9, D20, D52, D53, D58, D75, D90, D92, D95, D130, D134 | It is characterized by aspects that relate to training in e-learning skills for both students and teachers concerning the use of the LMS platform and emerging technologies, as well as factors related to assistance and technical support in using the platform and technological tools during the course development |

| Course information or academic program | D1, D22, D23, D24, D40, D49, D62, D102, D112, D114, D125, D128 | It is characterized by the dissemination and publication of course information such as justification, objectives, study plan, entry, exit profile, and information on the teaching and technical staff. |

| Rules and regulations | D3, D12, D16, D22, D55, D57, D69, D80, D94, D113, D133 | It is characterized by the existence of policies and regulations concerning virtual education, in aspects such as e-learning instructions and guidelines for both teachers and students, as well as management of student complaints, evaluation, qualification, and academic honesty |

| Institutional organization | D11, D39, D46, D56, D88, D93, D110, D126 | Characterized by aspects that go beyond the course and focus on parts of a structure under which online training processes are managed |

| Teacher support | D52, D60, D75, D77, D78, D104 | It is characterized by aspects related to administrative support in terms of working conditions, intellectual property, pedagogical support, and strategies that pursue the professional development of teachers |

| Economics and technological financing | D8, D69, D96, D111, D113, D128, D133 | Characterized by aspects related to allocating economic resources for virtual education and their management. |

| e-assessment | D18, D32, D45, D68, D116 | Characterized by the aspects that relate to the process of measuring the achievement of learning results of a course, considering that the evaluation is precise and consistent with the objectives of the course and with adequate scenarios, notified and provided feedback on time by the teacher, in correspondence to institutional qualification and evaluation policies and regulations |

| Admission | D2, D25, D117, D124 | Characterized by the process carried out for the admission of a student to the program or course, considering aspects such as dissemination strategies, promotion, evaluation of knowledge and minimum necessary skills, registration, among others |

| Research and innovation | D69, D106, D126, D132 | Characterized by aspects related to strategies and efforts in research and innovation in virtual education. |

| Teacher Profile | D28, D41, D63, D121 | Characterized by assessing the skills that the person who teaches classes should have. |

| Link with society | D51, D118, D119, D132 | Characterized by aspects related to student participation in the community. |

| Diversity | D87 | Characterized by aspects related to social influence, cultural diversity, prejudices of diversity, accessibility to information, and legal aspects, which revolve around the actors of virtual education |

| Knowledge management | D7 | Characterized by aspects that are oriented to the sharing/reuse of resources, as well as the existence of formats and processes to document lessons learned and actions concerning the evaluation of teaching performance. |

References

- Durán, R.; Estay-Niculcar, C.; Álvarez, H. Adopción de buenas prácticas en la educación virtual en la educación superior. Aula Abierta. 2015, 43, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akour, M.; Alenezi, M.; Al Sghaier, H.; Al Shboul, Y. The COVID-19 pandemic: When e-learning becomes mandatory not complementary. Int. J. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2021, 13, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaiah, M.; Al-Khasawneh, A.; Althunibat, A. Exploring the critical challenges and factors influencing the E-learning system usage during COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 5261–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocheva, M.; Kasakliev, N.; Somova, E. E-Learning during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Empirical Research. Math Inform. 2021, 64, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESCO Roadmap for Implementing the Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development—UNESCO Biblioteca Digital. 2014. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230514 (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- UN General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Kestin, T.; Van Den Belt, M.; Denby, L.; Ross, K.; Thwaites, J.; Hawkes, M. Getting Started with the SDGs in Universities. 2017. Available online: https://ap-unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/University-SDG-Guide_web.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- González-Zamar, M.D.; Abad-Segura, E.; López-Meneses, E.; Gómez-Galán, J. Managing ICT for Sustainable Education: Research Analysis in the Context of Higher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, R.; Sallán, J.G. Dimensiones de evaluación de calidad de educación virtual: Revisión de modelos referentes. RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2018, 21, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagarinho, J. Quality in learning: What should contain the definition? REDaPECI 2020, 20, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque Oliva, E.J.; Gómez, Y.D. Evolución conceptual de los modelos de medición de la percepción de calidad del servicio: Una mirada desde la educación superior. Suma Neg. 2014, 5, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ossiannilsson, E.; Williams, K.; Camilleri, A.F.; Brown, M. Quality Models in Online and Open Education around the Globe: State of the Art and Recommendations. International Council for Open and Distance Education. 2015. Available online: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A69277 (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Hilera González, J.R.; Hoya Marin, R. Estándares de E-Learning: Guía de Consulta. Universidad de Alcalá. 2010. Available online: http://www.hablemosdeelearning.com/2010/03/estandares-de-e-learning-guia-de.html (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- ESG. Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (ESG). European Students’ Union. 2015. Available online: http://www.esu-online.org (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Huertas, E.; Biscan, I.; Ejsing, C. Considerations for Quality Assurance of E-Learning Provision. JECP 2018, 1, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, G.H.; Askling, B.; Dittrich, K.; Froestad, W.; Haug, P.; Hofgaard Lycke, k.; Moitus, S.; Pyykkö, R.; Sørskår, A. Assessing Educational Quality Knowledge Production and the Role of Experts. European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education. 2009. Available online: http://www.enqa.eu/files/Assessing_educational_quality_wr6.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Vigo-Cuza, P.; Segrea González, J.; León Sánchez, B.; López Otero, T.; Pons Mena, J.; León Sánchez, C. Autoevaluación institucional. Una herramienta indispensable en la calidad de los procesos universitarios. MediSur 2014, 12, 727–735. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, K.L.; Owston, R. Evaluating e-learning accessibility by automated and student-centered methods. Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 2016, 64, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, J.K. E-Learning and Disability in Higher Education: Accessibility Research and Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, M.; Ellis, K.; Giles, M. Students with Disabilities and eLearning in Australia: Experiences of Accessibility and Disclosure at Curtin University. TechTrends 2018, 62, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossiannilsson, E.; Landgren, L. Quality in e-learning—A conceptual framework based on experiences from three international benchmarking projects. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2012, 28, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality Education. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Perales Jarillo, M.; Pedraza, L.; Moreno Ger, P.; Bocos, E. Challenges of Online Higher Education in the Face of the Sustainability Objectives of the United Nations: Carbon Footprint, Accessibility and Social Inclusion. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, J. Sustainable Web Design. A List Apart. 2013. Available online: https://alistapart.com/article/sustainable-web-design/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Krippendorff, K. Computing Krippendorff’s Alpha-Reliability. Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/43/ (accessed on 26 September 2021).

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. EBSE Tech. Rep. 2007, 2, 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Barzabal, L.M.; del Pilar Ortiz-Calderón, M.; Barcia-Tirado, D.M. Quality Indicators for Auditing on-Line Teaching in European Universities. TechTrends 2019, 63, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESVIAL. Modelo de Acreditación de Accesibilidad en la Educación Virtual. 2013. Available online: http://www.esvial.org/guia/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Elaboraci%C3%B3n-de-un-modelo-de-acreditaci%C3%B3n-de-accesibilidad-en-la-educaci%C3%B3n-virtual.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- CALED (Instituto Latinoamericano y del Caribe de Calidad en Educación Superior a Distancia). Guía de Autoevaluación para Programas de Pregrado a Distancia. Universidad TÉcnica Particular de Loja: Loja, Ecuador, 2010; Available online: https://www.uladech.edu.pe/images/stories/universidad/documentos/2012/Guia-Autoevaluacion-Programas-Pregrado-CALED.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Consejo Nacional de Acreditación de Colombia. Autoevaluación con Fines de Acreditación de Programas de Pregrado. 2013. Available online: https://www.cna.gov.co/1741/articles-186376_guia_autoev_2013.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- CIEES. Principios y Estándares Para la Evaluación y Acreditación de Programas Educativos en Instituciones de Educación Superior 2017. Modalidad a Distancia. 2018. Available online: https://www.ciees.edu.mx/documentos/principios-y-estandares-para-la-evaluacion-y-acreditacion-de-programas-educativos-modalidad-a-distancia.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- SINAES. Modelo de Acreditación Oficial de Carreras de Grado del Sistema Nacional de Acreditación de la Educación Superior para la Modalidad a Distancia. 2021. Available online: https://www.sinaes.ac.cr/documentos/Manual_de_Acreditacion_de_Carreras_de_Grado_Modalidad_a_Distancia.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- EFQUEL. UNIQUe—European Universities Quality in e-Learning. Certifying Excellence in Institutional TEL. 2011. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20150325224430/http://cdn.efquel.org/wp-content/blogs.dir/5/files/2012/09/UNIQUe_guidelines_2011.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Ahel, O.; Lingenau, K. Opportunities and Challenges of Digitalization to Improve Access to Education for Sustainable Development in Higher Education. In Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals; World Sustainability Series; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development. 2013. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Jafari, E.; Alamolhoda, J. Lived Experience of Faculty Members of Ethics in Virtual Education. In Technology, Knowledge and Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilan, R.; Fernandez, P. Quality Framework on Contextual Challenges in Online Distance Education for Developing Countries; Computing Society of the Philippines: Quezon City, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hadullo, K.; Oboko, R.; Omwenga, E. A model for evaluating e-learning systems quality in higher education in developing countries. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using ICT 2017, 13, 185–204. Available online: http://ijedict.dec.uwi.edu/viewarticle.php?id=2311 (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Farid, S.; Ahmad, R.; Alam, M.; Akbar, A.; Chang, V. A sustainable quality assessment model for the information delivery in E-learning systems. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2018, 46, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, E.; Roca, R.; Moehren, J.; Ranne, P.; Gourdin, A. External Evaluation of e-Assessment—A Conceptual Design of Elements to be Considered. 2017. Available online: https://eua.eu/resources/publications/494:external-evaluation-of-e-assessment-%E2%80%93-a-conceptual-design-of-elements-to-be-considered.html (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Mejía-Madrid, G.; Molina-Carmona, R. Model for Quality Evaluation and Improvement of Higher Distance Education Based on Information Technology. ResearchGate. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311508177_Model_for_quality_evaluation_and_improvement_of_higher_distance_education_based_on_information_technology (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Luna, E.; Ponce, S.; Cordero, G.; Cisneros-Cohernour, E. Marco para evaluar las condiciones institucionales de la enseñanza en línea. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2018, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadzhikoleva, S.; Orozova, D.; Andonov, N.; Hadzhikolev, E.; Pasheva, V.; Popivanov, N.; Venkov, G. Generalized net model of a system for quality assurance in higher education. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2172, 040005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, E.H.; Solà, R.R.; Ivanova, M.; Rozeva, A.; Durcheva, M. Internal Quality Assurance Procedures Applicable to eassessment: Use Case of the tesla project. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th International Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (ITHET), Olhao, Portugal, 26–28 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istrate, O. Open Online Training for Humanitarians: The Pedagogical Background of RCRC Learning Platform. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Virtual Learning ICVL 2016, Craiova, Romania, 29 October 2016; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35541760/Open_Online_Training_for_Humanitarians_the_Pedagogical_Background_of_RCRC_Learning_Platform (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Romero-Pelaez, A.; Segarra-Faggioni, V.; Piedra, N.; Tovar, E. A Proposal of Quality Assessment of OER Based on Emergent Technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 8–11 April 2019; 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1114–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CACES. Modelo de Evaluación Externa de Universidades y Escuelas Polítécnicas 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.caces.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2019/12/3.-Modelo_Eval_UEP_2019_compressed.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- Latchem, C. Open and Distance Learning Quality Assurance in Commonwealth Universities: A Report and Recommendations for QA and Accreditation Agencies and Higher Education Institutions. Commonwealth of Learning (CO)L. 2016. Available online: http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/2046 (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Martín Núñez, J.L.; Bravo Ramos, J.L.; Hilera González, J.R. Indicators for Assessing the Quality of a Blended University Course. IEEE Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. Aprendiz. 2017, 12, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.G. Evaluación y Acreditación de los Programas a Distancia o en Línea: Breve Revisión de Algunos Modelos. 2015. Available online: https://reposital.cuaed.unam.mx:8443/xmlui/handle/20.500.12579/4053 (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Martin, F.; Kumar, S. Frameworks for Assessing and Evaluating e-Learning Courses and Programs. In Leading and Managing e-Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaine, I. Quality Assessment of Electronic Learning Materials. In Research for Rural Development. International Scientific Conference Proceedings (Latvia); Latvia University of Agriculture: Jelgava, Latvia, 2015; Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=LV2016000367 (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Orellana, V.; Cevallos, Y.; Tello-Oquendo, L.; Inca, D.; Palacios, C.; Rentería, L. Quality Evaluation Processes and Its Impulse to Digital Transformation in Ecuadorian Universities. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth International Conference on EDemocracy EGovernment (ICEDEG), Quito, Ecuador, 24–26 April 2019; pp. 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanita, E.; Prastiti, N.; Purnomo, M.o.h.A.; Suparmi, A.; Nugraha, D.A. Measurement of e-learning quality based on ISO 19796-1 using fuzzy analytical network process method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 2014, 020155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S. A Quality Framework for Continuous Improvement of E-learning: The e-Learning Maturity Model. 2010. Available online: http://www.ijede.ca/index.php/jde/article/view/606 (accessed on 14 September 2020).

- Online Learning Consortium. OLC Quality Scorecard—OSCQR Course Design Review Scorecard. OLC. 2019. Available online: https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/consult/olc-quality-scorecard-suite/ (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, Y.L. Quality Assurance in e-Learning: PDPP evaluation model and its application. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2012, 13, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, H.; Johansson, M.; Westman, P.; Åström, E. e-Learning Quality: Aspects and Criteria for Evaluation of e-Learning in Higher Education; Högskoleverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Acreditación de Colombia. Componentes del Modelo de Acreditación en Alta Calidad—CNA. 2020. Available online: https://www.cna.gov.co/portal/Modelo-de-Acreditacion/Contexto/402547:Componentes-del-modelo-de-acreditacion-en-Alta-Calidad (accessed on 7 December 2021).

- Vorobyova, O.P. Quality Assurance of e-Learning in the European Higher Education Area. Inf. Technol. Learn. Tools 2018, 64, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Online Learning Consortium. OLC Quality Scorecard for the Administration of Online Programs. OLC. 2011. Available online: https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/consult/olc-quality-scorecard-administration-online-programs/ (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Masoumi, D.; Lindstrom, B. Quality in E-Learning: A Framework for Promoting and Assuring Quality in Virtual Institutions. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2012, 28, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.H. Comprehensive Approach to Program Evaluation in Open and Distributed Learning (CAPEODL Model); George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Term | Synonyms |

|---|---|

| model | standard, guideline, normative, criteria |

| quality evaluation | quality assessment, QA |

| higher education | college, university, technological institute |

| e-learning | e-learning, virtual education |

| Identification | Screening | Elegibility | Included | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32,200 | 110 | 29 | 9 | |

| Google Scholar | 762 | 109 | 29 | 9 |

| Scopus | 166 | 83 | 24 | 8 |

| Web of Science | 46 | 44 | 15 | 9 |

| IEEExplore | 22 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| Eric | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 33,199 | 356 | 110 | 37 |

| Accessibility Features | Related Criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Content accessibility | A8, A9, A13, A15, A16, A20, A23, A24, A25, A28, A29, A30, A31, A33, A35, A36, A39, A41, A42, A46, A52, A53 | View from the accessibility of the contents, resources, course information, program, or LMS platform, in relation to compliance with web content accessibility standards |

| Training | A2 | View as the training of students and teaching staff in the use of the platform and e-learning resources |

| Alternative content | A11, A17, A18, A32, A48 | View from the institution’s availability to provide course information and other resources in alternative media for students who do not have permanent internet access. |

| Continuity of service and access to internet and ICTs | A3, A6, A26, A27, A50 | Seen from the guarantee of continuous and uninterrupted access to the LMS platform and the possibility of making internet access or ICT resources available to students and teachers, such as loans from various locations, including outside the institution |

| Curriculum flexibility | A7, A10, A22, A37, A38, A40 | It refers to aspects that enable a flexible, open, and inclusive curriculum, which allows flexible learning based on the needs and abilities of a student |

| Accessibility policies | A12, A44, A51 | The institution, program, or course has defined accessibility policies |

| Assistive technologies | A34, A42 | View from the availability of learning materials or assistive technology for students or teachers who require it |

| Usability | A1, A5, A14, A19, A21, A36, A41, A42, A43, A45, A47, A49, A50 | View from aspects that are related to ease of use, adequate navigability, good design, among others that the virtual education platform presents |

| Model | Praxis (Steps Are Numbered Systematically) |

|---|---|

| Torres-Barzabal—2019 [27] |

|

| Esvial Accessibility Accreditation Model—2013 [28]. Two-phase model. | Self-assessment:

|

| Caled—2010 [29] |

|

| Colombia Accreditation Model—2013 [30] |

|

| Mexico Accreditation Model—2018 [31] |

|

| Accreditation Model of Costa RICA—2011 [32] |

|

| UNIQUe EFQUEL—2011 [33] |

|

| Phase or Sub-Process | Sub-Processes Included or Related | Description |

|---|---|---|

| C1, C12, C19, C24, C35, C36 | It constitutes the formalization phase of the need for evaluation by the institution before a certification or accreditation body or the same institution and its authorities |

| C2, C7, C13, C30 | It includes aspects related to the socialization of the model within the institution and training for self-assessment or self-diagnosis |

| C3, C6, C8, C14, C20, C25, C31, C37 | This corresponds to the preliminary self-assessment carried out, altogether with the preparation of a detailed report on compliance with the requirements of the quality criteria established in the model |

| C4, C9, C10, C15, C16, C21, C26, C32, C38 | It constitutes the on-site visit to the institution evaluated by a group of peer evaluators (experts) to determine the extent of compliance with the quality standards of the model through observation and verification of the facts declared in the self-assessment report |

| C5, C11, C17, C22, C27, C28, C33, C39 | It constitutes the declaration of Certification or Acreditation of the institution, program, or course evaluated, accompanied by a report of the findings and in cases the conditions or actions susceptible of improvement with which the certification is granted |

| C18, C29, C34, C40 | It refers to the continuous improvement thread to which the institution is committed based on the specific recommendations under which the certification or accreditation was granted, including an improvement plan proposed by the institution |

| C23 | It includes public recognition of the quality achieved by the institution |

| Dimension | Standards | Requirements | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | 5 | 16 | 19 |

| Student body | 3 | 9 | 13 |

| Teaching | 5 | 14 | 19 |

| Infrastructure | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Total | 16 | 48 | 63 |

| Dimension/Standard | |

|---|---|

| 1. Organization | |

| 1.1. Organization: The institution has an organizational structure and a set of rules, policies, and regulations that support virtual education processes, highlighting accessibility and inclusion, as well as quality assurance and continuous improvement. 1.2. Information on the academic course or program: The public institution disseminates relevant information on the academic course or program in a clear and up-to-date manner that enables students to understand it fully. 1.3. Economy and technological financing: The institution has regulations and executes actions that guide the improvement and updating of the computer platform 1.4. Knowledge management: The institution has and applies regulations and procedures that guide the management of the knowledge generated within the different virtual education processes. 1.5. Research and innovation: The institution has regulations and executes actions that guide the improvement and updating of the computer platform that supports virtual education and other related processes. | |

| 2. Student body | |

| 2.1. Student support: The institution applies regulations and procedures that seek comprehensive education and student well-being in the academic, personal-social, and psychological spheres, according to the student’s profile and their particular needs. 2.2. Admission: Regarding the admission process to the program/career or course, the institution considers strategies to pursue an adequate income without discrimination according to the student’s profile and needs. 2.3. Diversity and inclusion: The institution applies regulations and procedures that enable educational inclusion without discrimination around the different actors of virtual education. | |

| 3. Teaching | |

| 3.1. Professor profile: The institution has competent professors who can teach classes within a virtual education program or course. 3.2. Teacher support: The institution has regulations and procedures for the benefit of teachers and their day-to-day teaching practice. 3.3. Learning content and resources: The institution applies regulations and procedures that pursue a flexible curricular design and an adequate learning content and resources design. 3.4. Learning strategies: The institution implements learning strategies that revolve around the development of the course, seen from the teaching–learning methodology, the scenarios and resources used, and the interactivity and use of tools/resources for interaction between student and teacher. 3.5. E-assessment: The institution applies regulations and procedures that seek to measure the achievement of learning results, considering an accurate and consistent evaluation with the course’s objectives and with appropriate scenarios | |

| 4. Infrastructure | |

| 4.1. Technological infrastructure and equipment: The institution has a technological infrastructure that supports the virtual education process, the LMS platform, and technical equipment accessible to users who need it. Both the infrastructure and the equipment must provide a continuous service (24/7) and are conditioned to be accessible, robust, and safe. 4.2. Learning management platform: The institution has an accessible computer platform to support the virtual education process and administrative management. 4.3. Assistance and technical support: The institution guarantees assistance and training in e-learning skills for both students and teachers regarding the use of the LMS platform as well as other emerging technologies that support the training process | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Timbi-Sisalima, C.; Sánchez-Gordón, M.; Hilera-Gonzalez, J.R.; Otón-Tortosa, S. Quality Assurance in E-Learning: A Proposal from Accessibility to Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053052

Timbi-Sisalima C, Sánchez-Gordón M, Hilera-Gonzalez JR, Otón-Tortosa S. Quality Assurance in E-Learning: A Proposal from Accessibility to Sustainability. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053052

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimbi-Sisalima, Cristian, Mary Sánchez-Gordón, José Ramón Hilera-Gonzalez, and Salvador Otón-Tortosa. 2022. "Quality Assurance in E-Learning: A Proposal from Accessibility to Sustainability" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053052

APA StyleTimbi-Sisalima, C., Sánchez-Gordón, M., Hilera-Gonzalez, J. R., & Otón-Tortosa, S. (2022). Quality Assurance in E-Learning: A Proposal from Accessibility to Sustainability. Sustainability, 14(5), 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053052