Effects of Hallyu on Chinese Consumers: A Focus on Remote Acculturation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Research Model

2.1. Hallyu Cultural Contents

2.2. Hallyu Image

2.3. Hallyu Cultural Familiarity

2.4. Remote Acculturation

2.5. Hallyu Effects

2.5.1. Attitudes toward Korea

2.5.2. Visit Intention to Korea

2.5.3. Purchase Intention of Korean Products

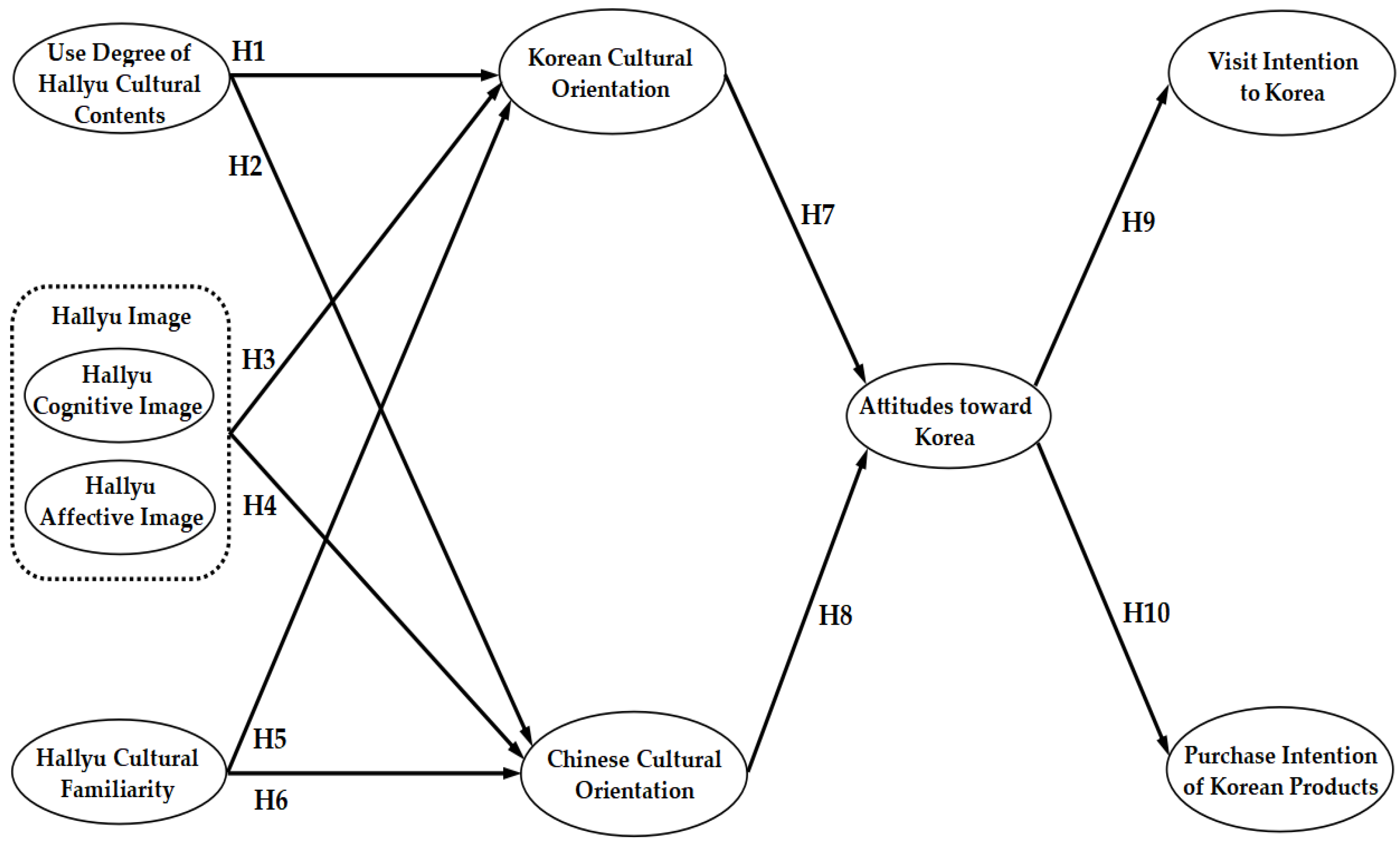

2.6. Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.2.1. Entire Variables’ Model

4.2.2. Sub-Factors’ Model

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferguson, G.M. The Big Difference a Small Island Can Make: How Jamaican Adolescents Are Advancing Acculturation Science. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.; Bornstein, M.H. Remote acculturation: The “Americanization” of Jamaican Islanders. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2012, 36, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.T.; Ferguson, Y.L.; Ferguson, G. “I am Malawian, Multicultural or British”: Remote acculturation and identity formation among urban adolescents in Malawi. J. Psychol. Afr. 2017, 27, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, G. The Korean Wave in China: Selective reception, resistance, transformation and marginalization. Sino-Soviet Aff. 2009, 32, 98–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, B.L. Study on a New “Korean Wave” from the Perspective of Intercultural Communication—Taking “My Love from The Star” as the Center. Master’s Thesis, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China, 2015. Available online: https://www.doc88.com/p-2002373258442.html?r=1 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Ferguson, G.; Adams, B.G. Americanization in the Rainbow Nation: Remote acculturation and psychological well-being of South African emerging adults. Emerg. Adulthood 2015, 4, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.M.; Bornstein, M.H. Remote acculturation of early adolescents in Jamaica towards European American culture: A replication and extension. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2015, 45, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferguson, G.; Muzaffar, H.; Iturbide, M.I.; Chu, H.; Gardner, J.M. Feel American, Watch American, Eat American? Remote Acculturation, TV, and Nutrition Among Adolescent-Mother Dyads in Jamaica. Child Dev. 2017, 89, 1360–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Arillo-Santillán, E.; Unger, J.; Thrasher, J. Remote Acculturation and Cigarette Smoking Susceptibility Among Youth in Mexico. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2018, 50, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Blanco, E.I.; Unger, J.B.; Thrasher, J.F. E-cigarette use susceptibility among youth in Mexico: The roles of remote acculturation, parenting behaviors, and internet use frequency. Addict. Behav. 2020, 113, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overview of United States. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/united-states (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Kim, S.K. A Study on the Effects of Chinese Consumers’ Familiarity with Korean Culture on Korean Cosmetics Purchase Intention: A Focus on the Mediating Effects of Attitude. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea, 2017. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T14446427 (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Han, D.J.; Cho, I.H. A Study on the Influence of Hallyu Cultural Contents on Intention to Visit Chinese Tourists—A Focused on The Mediating Effect of National Image. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2017, 11, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.P. The Effect of Hallyu Cultural Contents Consumption on Attitude and Purchase Intention toward Commodities. Master’s Thesis, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, Korea, 2016. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T14177719 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Kim, S.-P.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, M.-S. Effects of Korean Wave Image Influences on the Purchase Intention of Korean Educational Product -Focus on the Controlling Effects of Engagement in Chinese University Students. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2013, 13, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, S.; Scott, D.; Kim, H. Celebrity fan involvement and destination perceptions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.W.; Nam, S.J.; Park, S.C.; Jin, J.H. The Analysis on the Economic Effects of Korean Wave(“Hallyu”) in China. J. Mod. China Stud. 2014, 15, 117–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eales, L.; Gillespie, S.; Eckerstorfer, S.; Eltag, E.M.; Ferguson, G.M. Remote Acculturation 101: A Primer on Research, Implications, and Illustrations from Classrooms Around the World. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2020, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H. A Study of the Effect on Chinese Tourists Consumption Behavioral of Korean Food Related on Their Familiarity with the Korea Wave—By the Theory of Planned Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Youngsan University, Yangsan, Korea, 2013. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T13229116 (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Lee, Y.H.; Park, D.H. A study of the effect on Chinese tourists consumption behavioral intentions of Korean food related on their familiarity with the Korea Wave—By the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Stud. 2014, 16, 97–117. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A104810405 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Moon, H.J.; Park, S.H. A Study the Relation between Popular Factors and Likability of Hallyu and the National Image. J. Public Relat. 2012, 16, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. The Korean Wave (Hallyu) in East Asia: A Comparison of Chinese, Japanese, and Taiwanese Audiences Who Watch Korean TV Dramas. J. Asian Soc. 2012, 41, 103–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.G. A study on influence of Korean Wave cultural contents satisfaction & national image by K-DRAMA character-istic in China. J. Korea Entertain. Ind. Assoc. 2014, 8, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J. The New Korean Wave in China: Chinese Users’ Use of Korean Popular Culture via the Internet. Int. J. Contents 2014, 10, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. An Assessment of the Image of Mexico as a Vacation Destination and the Influence of Geographical Location Upon That Image. J. Travel Res. 1979, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Richardson, S.L. Motion picture impacts on destination images. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Brinberg, D. Affective Images of Tourism Destinations. J. Travel Res. 1997, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. A model of destination image formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Hosany, S. Destination Personality: An Application of Brand Personality to Tourism Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2006, 45, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gartner, W.C. Image Formation Process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.W.; Li, X.; Pan, B.; Witte, M.; Doherty, S.T. Tracking destination image across the trip experience with smartphone technology. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.H. Effect of Chinese Tourists’ Hallyu Image on Motives and Selection Attributes of Visiting at Drama and Movie Shooting Sites. Master’s Thesis, Cheongju University, Chungbuk, Korea, 2015. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T13812292 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchinson, J.W. Dimensions of Consumer Expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.B. Understanding Destination Choice from a Cultural Distance Perspective. Master’s Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2668 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Toyama, M.; Yamada, Y. The Relationships among Tourist Novelty, Familiarity, Satisfaction, and Destination Loyalty: Beyond the Novelty-familiarity Continuum. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2012, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettman, J.R.; Park, C.W. Effects of Prior Knowledge and Experience and Phase of the Choice Process on Consumer Decision Processes: A Protocol Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S. Image variations of Turkey by familiarity index: Informational and experiential dimensions. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R. The distant familiar?: Young British adults’ imaginings of Australia. In Riding the Wave of Tourism and Hospitality Research; Braithwaite, R.L., Braithwaite, R.W., Eds.; Southern Cross University: Lismore, Australia, 2003; pp. 846–862. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.843137244391775 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Redfield, R.; Linton, R.; Herskovits, M.J. Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. Am. Anthropol. 1936, 38, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. Globalisation and acculturation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2008, 32, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S. A Study of Chinese Students’ Attitude toward Korea: Focused on U-Curve Theory and Cultural Adjustment. Master’s Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea, 2012. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T12955379 (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Lee, H.S. A Study of International Students’ Attitude Formation Process Regarding Their Host Country from the Perspective of Public Diplomacy—Chinese students in Korea. Ph.D. Thesis, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea, 2013. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T13278835 (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Lee, H. A Study of Chinese International Students’ Attitude Formation Process Regarding Korea—From the Perspective of Public Diplomacy. Asian Cult. Stud. 2014, 34, 229–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.-W.; Han, M.; Wong, S.L. Cultural Orientation in Asian American Adolescents: Variation by age and ethnic density. Youth Soc. 2007, 39, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, G.R.; Haddock, G. The Psychology of Attitudes and Attitude Change; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, D.Y.; Won, H.J.; Kim, T.I. Impact of Overseas Taekwondo Demonstration Performance Quality on State Image, Attitude toward Korea and Intention to visit Korea. J. Korean Alliance Martial Arts 2013, 15, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, H.C. Nationalism, patriotism, and national identity: Social-psychological dimensions. In Patriotism in the Lives of Individuals and Nations; Bar-Tal, D., Staub, E., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997; pp. 165–189. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-97314-003 (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Schatz, R.T.; LaVine, H. Waving the Flag: National Symbolism, Social Identity, and Political Engagement. Polit. Psychol. 2007, 28, 329–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.C. Revisiting Group Attachment: Ethnic and National Identity. Polit. Psychol. 1999, 20, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, H.; Malova, D.; Hoogendoorn, S. Nationalism and Its Explanations. Polit. Psychol. 2003, 24, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.W.; Kim, S. National Pride in Comparative Perspective: 1995/96 and 2003/04. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2006, 18, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Org. Behav. Human Decis. Proc. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheon, D.H. The effects of new Hallyu cultural contents and business Hallyu on emotional image, attitude and visit Intention. Tour. Res. 2017, 32, 181–198. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, H.S. The effect of LOHAS Korean Waves on Korea images and attitude towards Korea. J. Tour. Sci. 2007, 31, 305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-B.; Kwon, K.-J. Examining the Relationships of Image and Attitude on Visit Intention to Korea among Tanzanian College Students: The Moderating Effect of Familiarity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, P.C.; Yeh, G.Y.-Y.; Hsiao, C.-R. The Effect of Store Image and Service Quality on Brand Image and Purchase Intention for Private Label Brands. Australas. Mark. J. 2011, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, M.K.; Zhou, L. Linking Product Evaluations and Purchase Intention for Country-of-Origin Effects. J. Glob. Mark. 2002, 15, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.Y.; Eum, M.R.; Lee, Y.J. The effect of wellbeing lifestyle on perceived value, brand preference and purchasing inten-tion: Focusing on environment-friendly brand in food service industry. Korea Acad. Soc. Tour. Leis. 2011, 23, 273–292. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A82660316 (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Feng, J.Y.; Mu, W.S.; Fu, Z.T. A review of consumer’s intention to buy. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2006, 2006, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.R.; Sousa-Filho, J.M.; Mota, M.D.O. Background of the purchase intention: Cosmopolitanism, image country and attitude in relation to countries. Braz. J. Mark.-BJM 2018, 17, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J. Influences of Globalization Factors of Korean Food on Country Image, Attitudes and Product Buying Intention to-ward Korea of Chinese and Japanese. Ph.D. Thesis, KyungHee University, Seoul, Korea, 2008. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T11168624 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Kim, J.M. Influence which Chinese Consumers’ Korean Wave Attitude Has on the Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention of Korean Products—Mainly about Korean Cosmetics after Deployment of THAAD. J. Korean Soc. Des. Cult. 2018, 24, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Kim, D.Y. China’s ‘ban on Korean culture’ and Chinese people’s attitudes toward Korea: Focusing on their experi-ence of Korea and Korean cultural products. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2019, 32, 123–151. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A106393834 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Molinillo, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Buhalis, D. DMO online platforms: Image and intention to visit. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.J.; Allen, C.T. Competitive Interference Effects in Consumer Memory for Advertising: The Role of Brand Familiarity. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Batra, R. Assessing the Role of Emotions as Mediators of Consumer Responses to Advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Jiang, L. How do destination Facebook pages work? An extended TPB model of fans’ visit intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2018, 9, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, T.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.E. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooi, E.; Sarstedt, M.; Mooi-Reci, I. Market Research: The Process, Data, and Methods Using Stata, 1st ed.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte. Limited: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. The Application of Electronic Computers to Factor Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2010-18801-000 (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.X. Restriction on South Korea and its influence on South Korea. Mod. Bus. 2017, 173–174. Available online: http://www.cqvip.com/qk/83634c/201729/7000363763.html (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Trivedi, R.H.; Patel, J.; Acharya, N. Causality analysis of media influence on environmental attitude, intention and behaviors leading to green purchasing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phinney, J.S. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.L.; Chentsova-Dutton, Y.; Wong, Y. Why and how we should study ethnic identity, acculturation, and cultural orientation. In Asian American Psychology: The Science of Lives in Context; Nagayama Hall, G.C., Okazaki, S., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Ahn, K.-M. Impact of K-pop on Positive Feeling Towards Korea, Consumption Behaviour and 1Intention to Visit from other Asian Countries. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2012, 12, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Lee, C.H.; Sun, S.S. A study on the effect of attitude toward a nation brand to the intentions of the nation’s product purchase: Focusing on the Chinese Hallyu (Korean Wave). Korea J. Commun. Stud. 2008, 16, 35–55. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A75556137 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Shin, B.-K.; Oh, M.-H.; Shin, T.-S.; Kim, Y.-S.; You, S.-M.; Roh, G.-Y.; Jung, K.-W. The Impact of Korean Wave Cultural Contents on the Purchase of Han-Sik (Korean food) and Korean Product—Based on the Survey of Asia (Japan, China), Americas and Europe. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 2014, 29, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, G.M. Remote acculturation and the birth of an Americanized Caribbean youth identity on the islands. In Caribbean Psychology: Indigenous Contributions to a Global Discipline; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, H.S.; Chae, K.J. Analyzing the trends in the academic studies on the Korean Wave. J. Hallyu Bus. 2014, 1, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, E.-S.; Chang, M.; Park, E.-S.; Kim, D.-C. The effect of Hallyu on tourism in Korea. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, S.; Giouvris, E. Tourist arrivals in Korea: Hallyu as a pull factor. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 23, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major Indicators of Tourism Statistics at a Glance. Available online: https://know.tour.go.kr/ (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Lim, Y.J. Research Models based on the Theory of Planned Behavior for Predicting Foreign Tourists’ Behavior toward Korean Wave Cultural Contents: Focused on Korean Soap Operas and Records. Ph.D. Thesis, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea, 2008. Available online: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=T11380408 (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Rhee, J.W. Mass communication effects of the ‘Hanliu’: Impacts of the Chinese’s use of Korean cultural products upon the attitudes towards Korea and intention to buy Korean products. Korea J. Commun. Stud. 2003, 47, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Y.L.; Ferguson, K.T.; Ferguson, G.M. I am AmeriBritSouthAfrican-Zambian: Multidimensional remote acculturation and well-being among urban Zambian adolescents. Int. J. Psychol. 2015, 52, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, G.M.; Dimitrova, R. Behavioral and Academic Adjustment of Remotely Acculturating Adolescents in Urban Jamaica. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2019, 2019, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar, I.; Arnold, B.; Maldonado, R. Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II: A Revision of the Original ARSMA Scale. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 1995, 17, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Items | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 207 | 38.7 |

| Female | 328 | 61.3 | |

| Age | Under 20 years old | 60 | 11.2 |

| 20–29 years old | 308 | 57.6 | |

| 30–39 years old | 144 | 26.9 | |

| 40–49 years old | 20 | 3.7 | |

| 50 years old and above | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Educational Background | Below high school graduation | 17 | 3.2 |

| High school graduation | 103 | 19.3 | |

| Junior college graduation | 135 | 25.2 | |

| College graduation | 205 | 38.3 | |

| Postgraduate school graduation or higher | 75 | 14.0 | |

| Occupation | Student | 165 | 30.8 |

| Housewife | 9 | 1.7 | |

| Office worker | 205 | 38.3 | |

| Civil servant | 35 | 6.5 | |

| Professional (e.g., teacher, lawyer, doctor) | 81 | 15.1 | |

| Individual business | 16 | 3.0 | |

| Other | 24 | 4.5 | |

| Monthly Income | Below 3000¥ | 170 | 31.8 |

| 3000¥–below 6000¥ | 125 | 23.4 | |

| 6000¥–below 10,000¥ | 130 | 24.3 | |

| 10,000¥–below 15,000¥ | 81 | 15.1 | |

| 15,000¥ and above | 29 | 5.4 |

| KMO | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | |

|---|---|---|

| Approximate Chi-Square | Degree of Freedom (df) | |

| 0.931 | 10,263.489 | 528 |

| Factors | Items | Mean | S.D. | Factor Loading | Commu Nality | Eigen Value | % of Variance | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use Degree of Hallyu Cultural Contents (HCC) | I watch Korean dramas frequently. (KD) | 4.89 | 1.734 | 0.724 | 0.634 | 2.841 | 8.608 | 0.810 |

| I watch Korean movies frequently. (KM) | 4.54 | 1.476 | 0.723 | 0.619 | ||||

| I watch or listen to K-Pop frequently. (KP) | 4.48 | 1.699 | 0.767 | 0.672 | ||||

| I watch K-variety shows frequently. (KV) | 3.97 | 1.513 | 0.737 | 0.651 | ||||

| Hallyu Cognitive Image (CI) | Hallyu is extremely friendly in my perception. (CI1) | 4.83 | 1.574 | 0.755 | 0.709 | 2.678 | 8.116 | 0.855 |

| Hallyu is extremely accessible in my perception. (CI2) | 5.14 | 1.549 | 0.597 | 0.696 | ||||

| Hallyu is extremely lively in my perception. (CI3) | 4.94 | 1.513 | 0.749 | 0.731 | ||||

| Hallyu is extremely interesting in my perception. (CI4) | 4.86 | 1.461 | 0.766 | 0.747 | ||||

| Hallyu Affective Image (AI) | Hallyu is arousing based on my feelings. (AI1) | 4.83 | 1.685 | 0.782 | 0.711 | 2.947 | 8.930 | 0.847 |

| Hallyu is pleasant based on my feelings. (AI2) | 4.66 | 1.550 | 0.780 | 0.701 | ||||

| Hallyu is exciting based on my feelings. (AI3) | 4.65 | 1.621 | 0.775 | 0.695 | ||||

| Hallyu is relaxing based on my feelings. (AI4) | 4.85 | 1.681 | 0.798 | 0.692 | ||||

| Hallyu Cultural Familiarity (HCF) | Regarding Hallyu culture, I am familiar. (HF1) | 4.76 | 1.808 | 0.902 | 0.873 | 2.629 | 7.968 | 0.919 |

| Regarding Hallyu culture, I am experienced. (HF2) | 5.09 | 1.852 | 0.879 | 0.845 | ||||

| Regarding Hallyu culture, I am knowledgeable. (HF3) | 4.88 | 1.820 | 0.900 | 0.866 | ||||

| Korean Cultural Orientation (KCO) | I like watching Korean dramas. (KO1) | 4.86 | 1.492 | 0.681 | 0.692 | 2.732 | 8.278 | 0.845 |

| I like watching Korean movies. (KO2) | 4.54 | 1.375 | 0.706 | 0.662 | ||||

| I like watching Korean TV programs. (KO3) | 4.53 | 1.445 | 0.713 | 0.681 | ||||

| I enjoy eating Korean food. (KO4) | 4.85 | 1.489 | 0.718 | 0.714 | ||||

| Chinese Cultural Orientation (CCO) | I like watching Chinese TV dramas. (CO1) | 2.69 | 1.517 | −0.794 | 0.739 | 2.971 | 9.003 | 0.860 |

| I like watching Chinese movies. (CO2) | 2.70 | 1.510 | −0.781 | 0.707 | ||||

| I like watching Chinese TV programs. (CO3) | 2.54 | 1.441 | −0.748 | 0.703 | ||||

| I enjoy eating Chinese food. (CO4) | 2.47 | 1.490 | −0.818 | 0.737 | ||||

| Attitudes toward Korea (ATK) | I am favorable toward Korea. (AT1) | 5.09 | 1.368 | 0.769 | 0.753 | 2.821 | 8.549 | 0.868 |

| I feel good toward Korea. (AT2) | 5.14 | 1.406 | 0.709 | 0.747 | ||||

| I am positive toward Korea. (AT3) | 4.86 | 1.342 | 0.769 | 0.729 | ||||

| I think Korea is likeable. (AT4) | 4.75 | 1.330 | 0.692 | 0.690 | ||||

| Visit Intention to Korea (VITK) | I intend to visit Korea in the future. (VI1) | 5.26 | 1.505 | 0.735 | 0.804 | 2.207 | 6.689 | 0.872 |

| It is likely that I will visit Korea in the future. (VI2) | 4.94 | 1.407 | 0.752 | 0.767 | ||||

| I plan to visit Korea in the future. (VI3) | 5.27 | 1.554 | 0.772 | 0.846 | ||||

| Purchase Intention of Korean Products (PIKP) | I find purchasing Korean products to be worthwhile. (PI1) | 4.77 | 1.426 | 0.757 | 0.745 | 2.350 | 7.120 | 0.860 |

| I will frequently purchase Korean products in the future. (PI2) | 4.87 | 1.577 | 0.757 | 0.816 | ||||

| I will strongly recommend others to purchase Korean products. (PI3) | 4.47 | 1.561 | 0.811 | 0.804 | ||||

| All Factors | 73.260 | 0.896 |

| Latent Variables | Items | Std. Estimate | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC | KD | 0.715 | 0.812 | 0.519 |

| KM | 0.702 | |||

| KP | 0.734 | |||

| KV | 0.730 | |||

| CI | CI1 | 0.739 | 0.854 | 0.595 |

| CI2 | 0.803 | |||

| CI3 | 0.766 | |||

| CI4 | 0.776 | |||

| AI | AI1 | 0.781 | 0.848 | 0.582 |

| AI2 | 0.773 | |||

| AI3 | 0.768 | |||

| AI4 | 0.729 | |||

| HCF | HF1 | 0.903 | 0.919 | 0.792 |

| HF2 | 0.871 | |||

| HF3 | 0.895 | |||

| KCO | KO1 | 0.790 | 0.845 | 0.577 |

| KO2 | 0.727 | |||

| KO3 | 0.743 | |||

| KO4 | 0.778 | |||

| CCO | CO1 | 0.800 | 0.860 | 0.605 |

| CO2 | 0.771 | |||

| CO3 | 0.773 | |||

| CO4 | 0.767 | |||

| AT K | AT1 | 0.762 | 0.868 | 0.621 |

| AT2 | 0.847 | |||

| AT3 | 0.765 | |||

| AT4 | 0.776 | |||

| VITK | VI1 | 0.861 | 0.875 | 0.701 |

| VI2 | 0.759 | |||

| VI3 | 0.886 | |||

| PIKP | PI1 | 0.754 | 0.861 | 0.675 |

| PI2 | 0.894 | |||

| PI3 | 0.811 |

| Latent Variable | HCC | CI | AI | HCF | KCO | CCO | ATK | VITK | PIKP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC | 0.720 | ||||||||

| CI | 0.479 | 0.771 | |||||||

| AI | 0.367 | 0.539 | 0.763 | ||||||

| HCF | 0.424 | 0.251 | 0.225 | 0.890 | |||||

| KCO | 0.636 | 0.699 | 0.412 | 0.345 | 0.760 | ||||

| CCO | −0.282 | −0.477 | −0.341 | −0.212 | −0.574 | 0.778 | |||

| ATK | 0.523 | 0.609 | 0.489 | 0.344 | 0.589 | −0.502 | 0.788 | ||

| VITK | 0.504 | 0.650 | 0.494 | 0.297 | 0.625 | −0.455 | 0.680 | 0.837 | |

| PIKP | 0.557 | 0.567 | 0.409 | 0.292 | 0.609 | −0.454 | 0.604 | 0.592 | 0.822 |

| Model Fit Indices | Evaluation Index (Acceptable Level) | Values of the Model |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | <3.0 | 1.632 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.971 |

| IFI | >0.90 | 0.971 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.967 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.929 |

| RMESA | ≤0.08 | 0.034 |

| Model Fit Indices | Evaluation Index (Acceptable Level) | Values of the Model |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | <3.0 | 2.781 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.931 |

| IFI | >0.90 | 0.931 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.922 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.896 |

| RMESA | ≤0.08 | 0.058 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Std. Estimate | C.R. | p | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | HCC→KCO | 0.426 | 8.962 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | HCC→CCO | −0.050 | −1.074 | 0.283 | Rejected |

| H3 | HI→KCO | 0.744 | 11.197 | *** | Supported |

| H4 | HI→CCO | −0.596 | −10.017 | *** | Supported |

| H5 | HCF→KCO | 0.113 | 2.986 | 0.003 | Supported |

| H6 | HCF→CCO | −0.082 | −1.893 | 0.058 | Rejected |

| H7 | KCO→ATK | 0.570 | 9.778 | *** | Supported |

| H8 | CCO→ATK | −0.223 | −4.541 | *** | Supported |

| H9 | ATK→VITK | 0.719 | 13.682 | *** | Supported |

| H10 | ATK→PIKP | 0.651 | 11.726 | *** | Supported |

| Model Fit Indices | Evaluation Index (Acceptable Level) | Values of the Model |

|---|---|---|

| CMIN/DF | <3.0 | 2.746 |

| CFI | >0.90 | 0.915 |

| IFI | >0.90 | 0.916 |

| TLI | >0.90 | 0.908 |

| NFI | >0.90 | 0.874 |

| RMESA | ≤0.08 | 0.057 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Std. Estimate | C.R. | p | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | HCC→KCO | 0.447 | 9.090 | *** | Supported |

| H2 | HCC→CCO | −0.086 | −1.787 | 0.074 | Rejected |

| H3a | CI→KCO | 0.606 | 11.627 | *** | Supported |

| H3b | AI→KCO | 0.084 | 2.087 | 0.037 | Supported |

| H4a | CI→CCO | −0.426 | −8.288 | *** | Supported |

| H4b | AI→CCO | −0.137 | −2.889 | 0.004 | Supported |

| H5 | HCF→KCO | 0.121 | 3.118 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H6 | HCF→CCO | −0.085 | −1.895 | 0.058 | Rejected |

| H7 | KCO→ATK | 0.553 | 9.955 | *** | Supported |

| H8 | CCO→ATK | −0.262 | −5.656 | *** | Supported |

| H9 | ATK→VITK | 0.710 | 13.313 | *** | Supported |

| H10 | ATK→PIKP | 0.642 | 11.433 | *** | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, L.; Jun, J.-W. Effects of Hallyu on Chinese Consumers: A Focus on Remote Acculturation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053018

Sun L, Jun J-W. Effects of Hallyu on Chinese Consumers: A Focus on Remote Acculturation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053018

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Lili, and Jong-Woo Jun. 2022. "Effects of Hallyu on Chinese Consumers: A Focus on Remote Acculturation" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053018

APA StyleSun, L., & Jun, J.-W. (2022). Effects of Hallyu on Chinese Consumers: A Focus on Remote Acculturation. Sustainability, 14(5), 3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053018