Social Media in Sustainable Tourism Recovery

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Using Social Media to Restore Tourism Sustainably

2.2. Generational and Gender Differences in Sharing Tourism Experiences through Social Media

3. Methods and Analysis

3.1. Data Collection and Research Sample

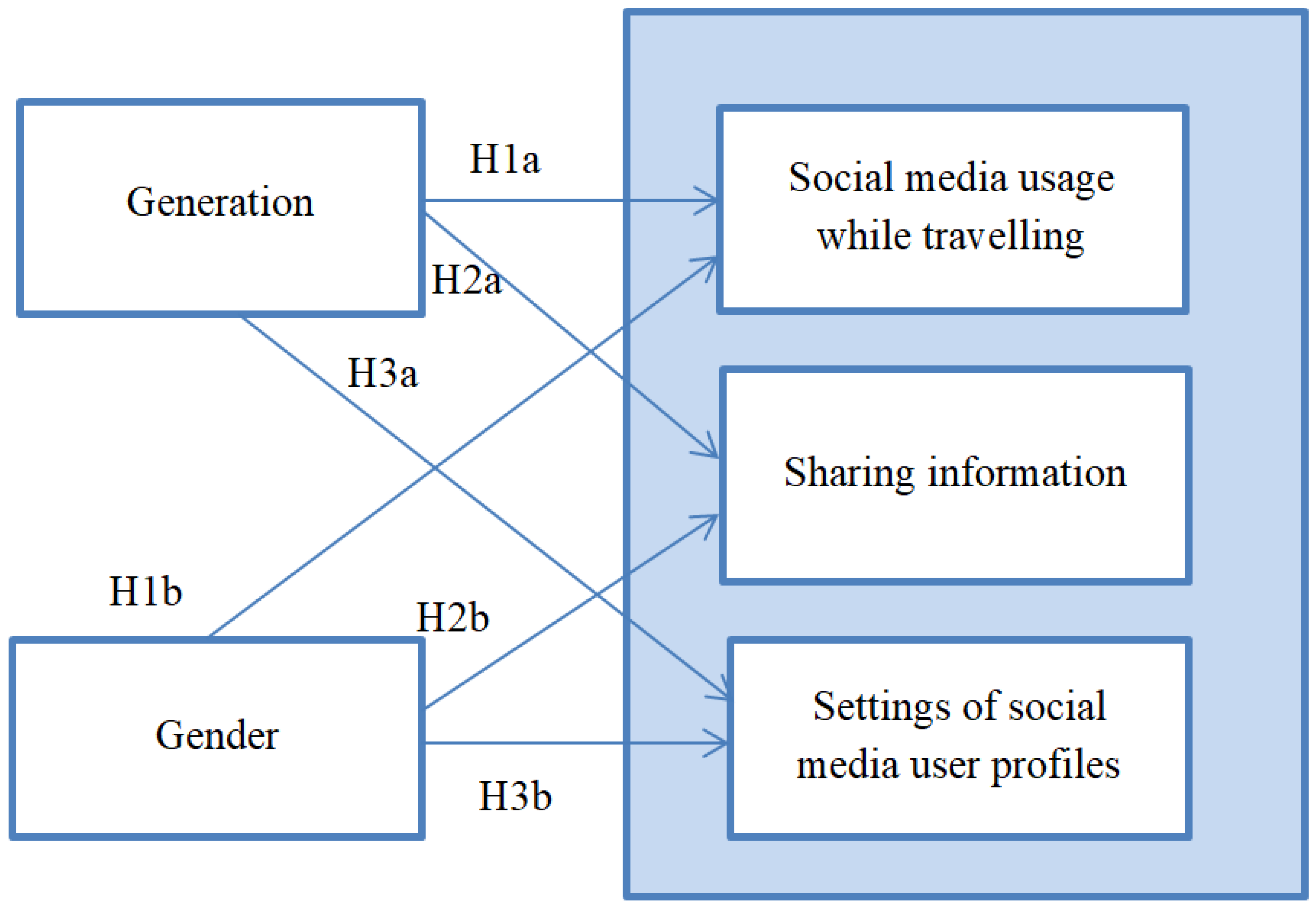

3.2. Research Model and Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

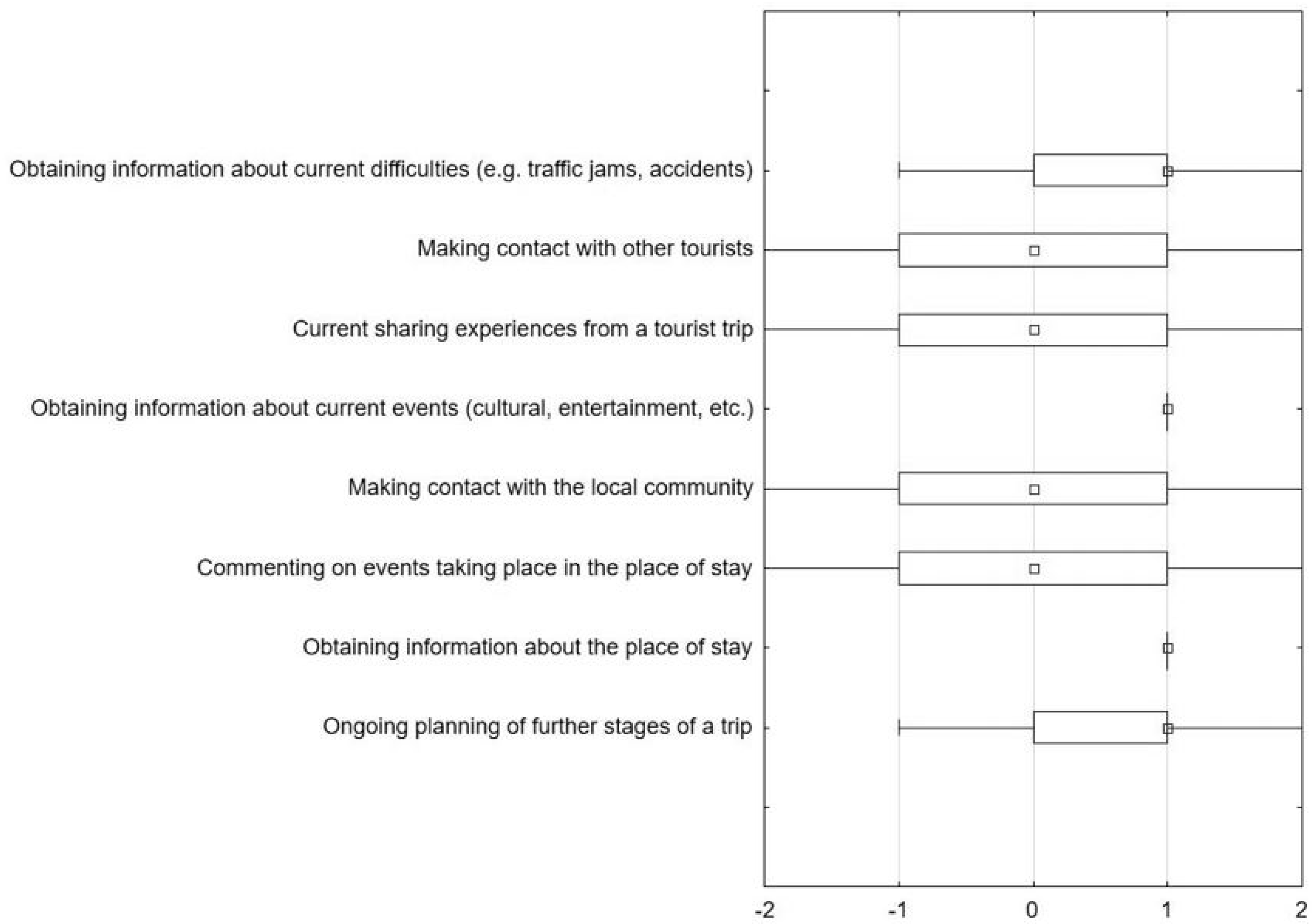

4.1. Using SM While Travelling

Discussion of the Obtained Results

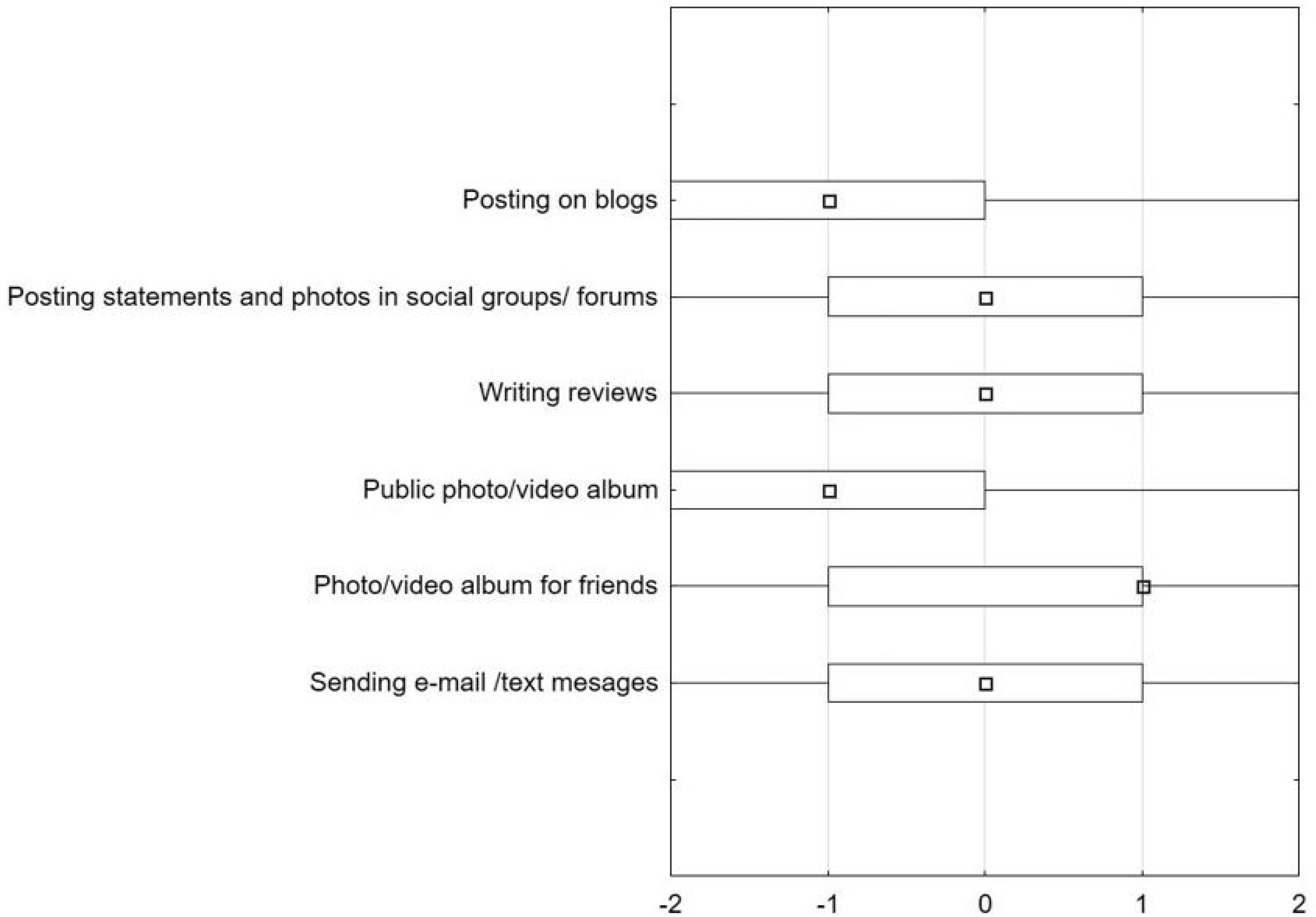

4.2. Using SM to Share Information

Discussion of the Obtained Results

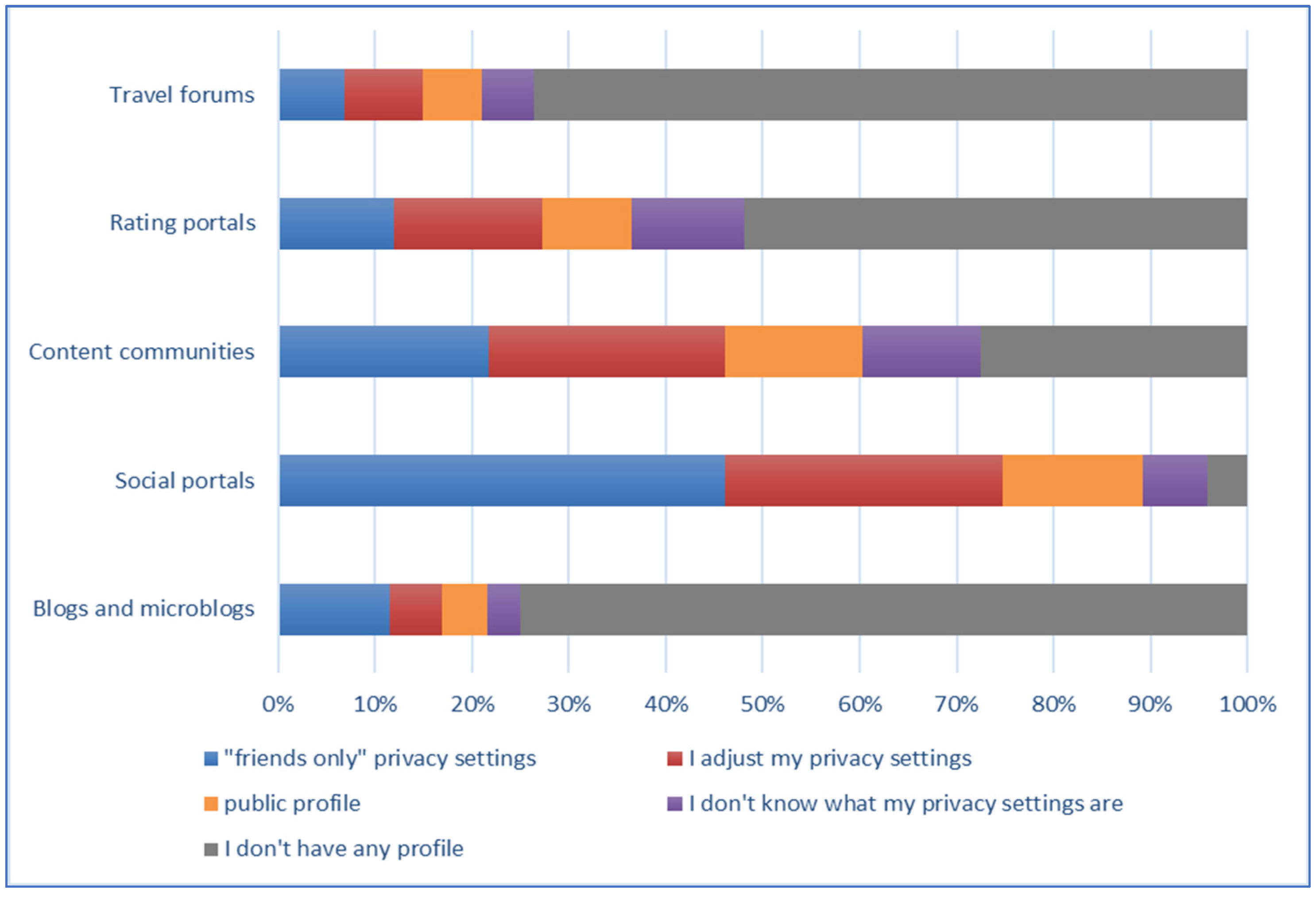

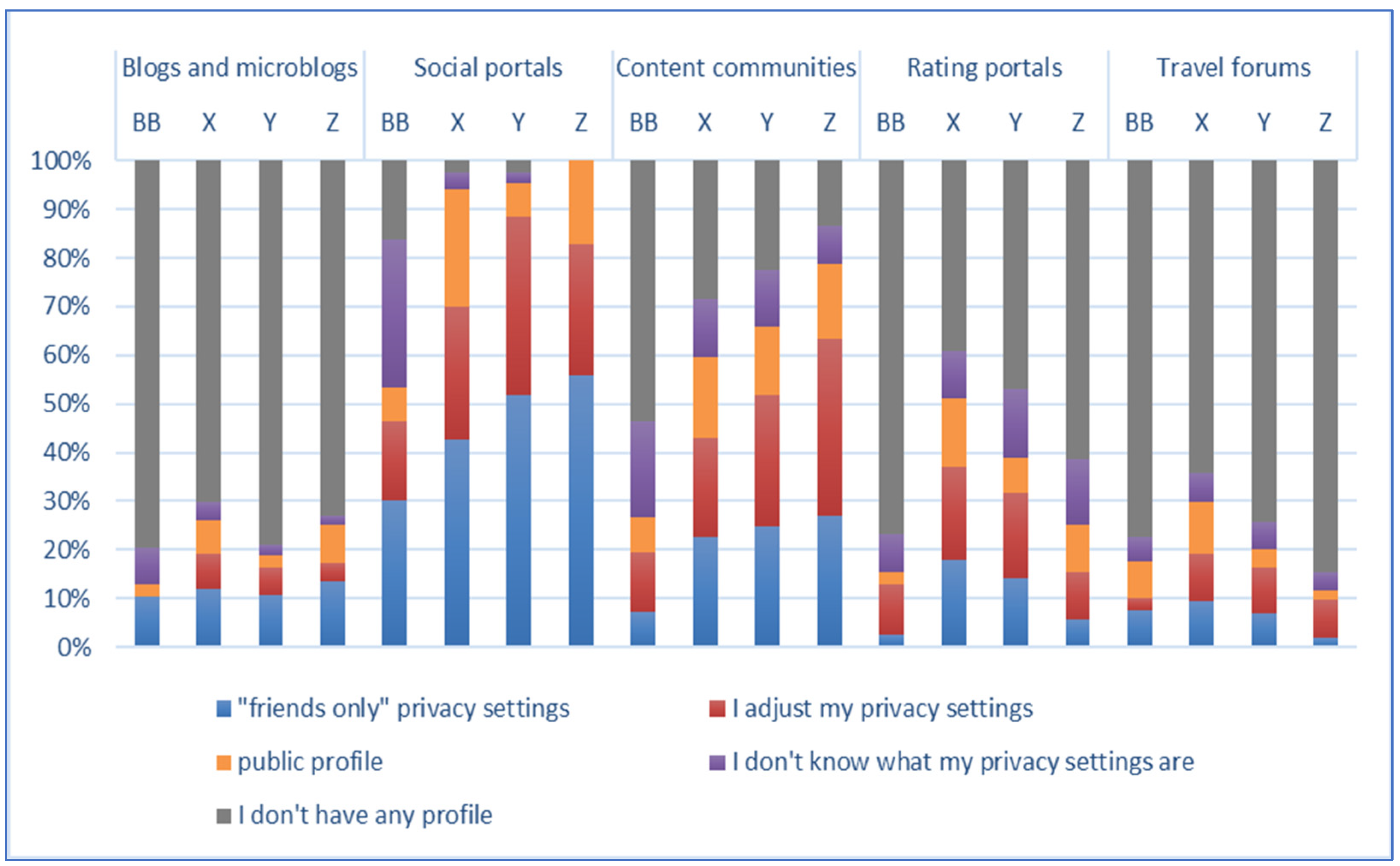

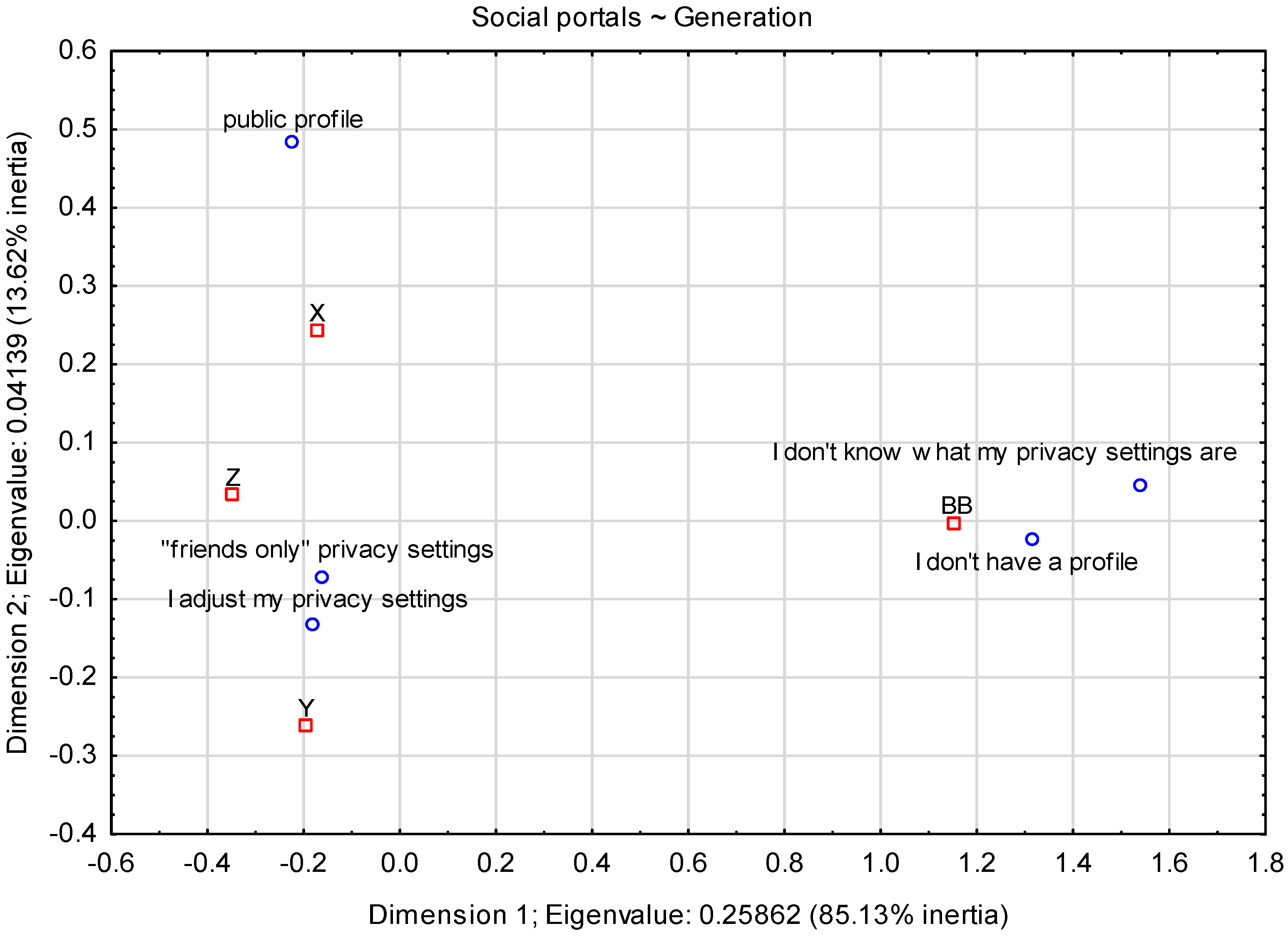

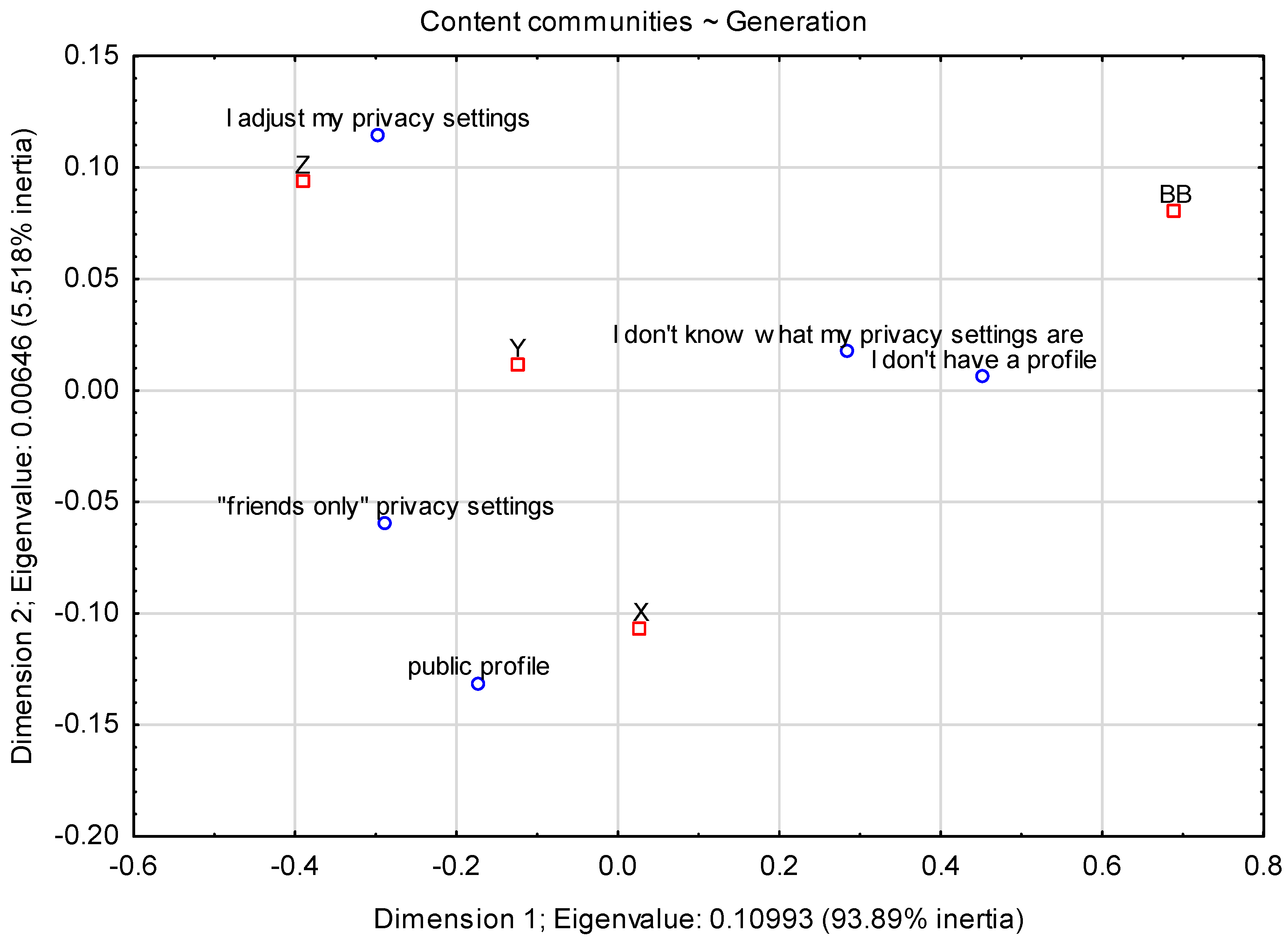

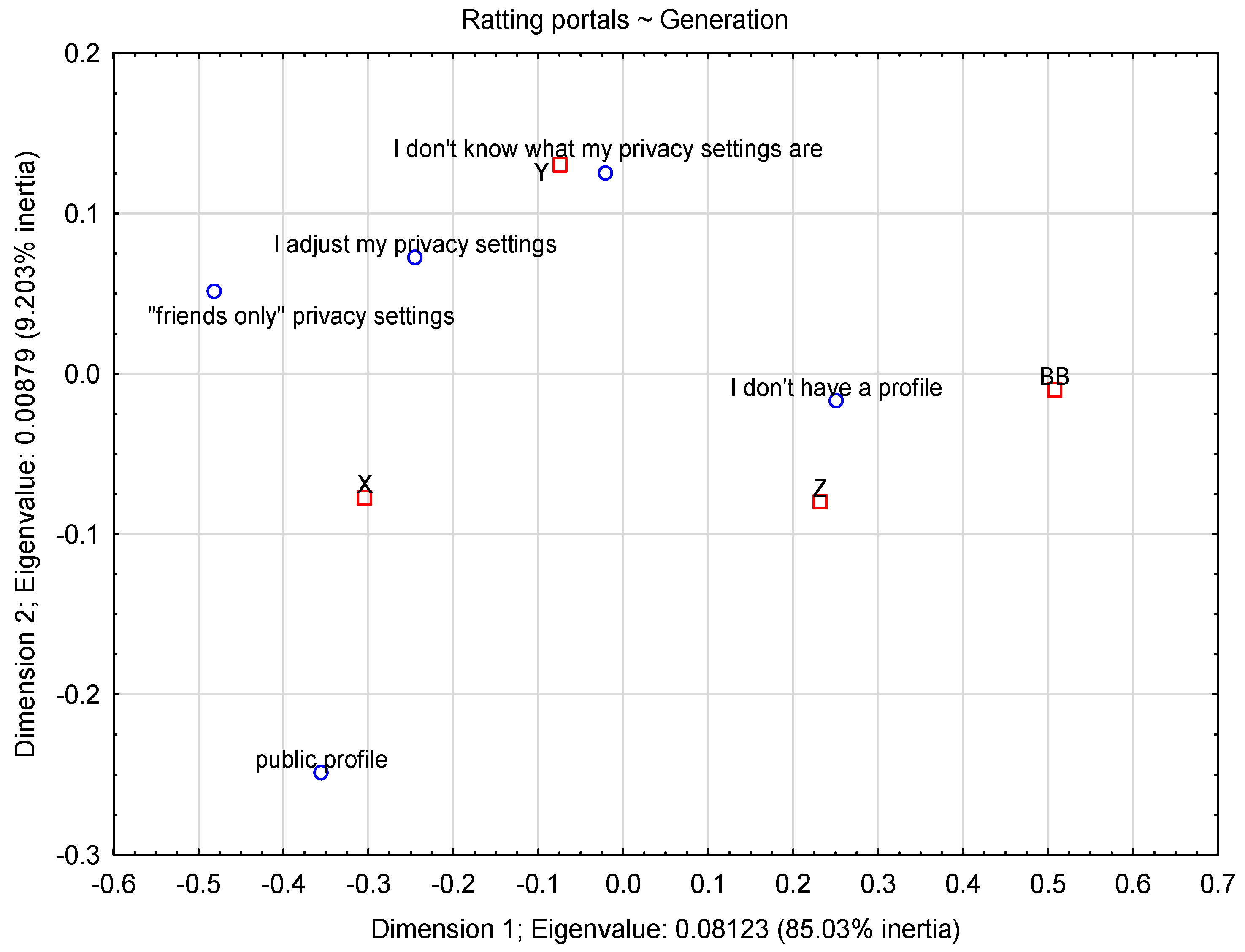

4.3. Profile Setting

Discussion of the Obtained Results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szromek, A.R.; Hysa, B.; Karasek, A. The Perception of Overtourism from the Perspective of Different Generations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNWTO Tourism. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/unwto-tourism-dashboard (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Allianz Research Turystyka: Europa Znajdzie się na Pierwszej Linii Wychodzenia z Kryzysu, ale Dopiero w Roku 2024. Portal Skarbiecbiz 2021. Available online: https://www.skarbiec.biz/gospodarka/turystyka-europa-znajdzie-sie-na-pierwszej-linii-wychodzenia-z-kryzysu-ale-dopiero-w-roku-2024.html (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Sołtysik-Piorunkiewicz, A.; Zdonek, I. How Society 5.0 and Industry 4.0 Ideas Shape the Open Data Performance Expectancy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamediana-Pedrosa, J.D.; Vila-Lopez, N.; Küster-Boluda, I. Secrets to Design an Effective Message on Facebook: An Application to a Touristic Destination Based on Big Data Analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1841–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livinec, M.; Adjiman, L. Tourism: Europe Will Be at the Frontline of the Recovery, but Only in 2024. Available online: https://www.eulerhermes.com/en_global/news-insights/economic-insights/Tourism-Europe-will-be-at-the-frontline-of-the-recovery-but-only-in-2024.html (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Yadav, J.K.; Verma, D.C.; Jangirala, S.; Srivastava, S.K. An IAD Type Framework for Blockchain Enabled Smart Tourism Ecosystem. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2021, 32, 100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, T.; Albanese, V.E. Online Place Branding for Natural Heritage: Institutional Strategies and Users’ Perceptions of Mount Etna (Italy). Heritage 2020, 3, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, C.; Huang, C.; Duan, L. The Concept of Smart Tourism in the Context of Tourism Information Services. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Woo, M.; Nam, K.; Chathoth, P.K. Smart City and Smart Tourism: A Case of Dubai. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Digital in Poland: All the Statistics You Need in 2021. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-poland (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- GUS SDG-Raport 2020 Polska Na Drodze Zrównoważonego Rozwoju. Available online: https://raportsdg.stat.gov.pl/2020/cel9.html (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Digital 2020: Poland. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-poland (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Akram, W.; Kumar, R. A Study on Positive and Negative Effects of Social Media on Society. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2017, 5, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.C.; Mader, D.R.D.; Mader, F.H. Using Social Media during the Hiring Process: A Comparison between Recruiters and Job Seekers. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2019, 29, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zoonen, W.; Verhoeven, J.W.M.; Vliegenthart, R. Understanding the Consequences of Public Social Media Use for Work. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, S.; Khan, M.M. Role of social media in promoting tourism in Pakistan. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 58, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Shankar, R.; Vrat, P. An Analysis of Industry 4.0 Implementation-Variables by Using SAP-LAP and e-IRP Approach. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Market Segmentation Based on the Environmentally Responsible Behaviors of Community-Based Tourists: Evidence from Taiwan’s Community-Based Destinations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, B.-L.; Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, M.J.; Han, H. Tourists’ Outbound Travel Behavior in the Aftermath of the COVID-19: Role of Corporate Social Responsibility, Response Effort, and Health Prevention. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 879–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, B.; Karasek, A.; Zdonek, I. Social Media Usage by Different Generations as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism Marketing in Society 5.0 Idea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walentek, D. Datafication Process in the Concept of Smart Cities. Energies 2021, 14, 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantoglou, M.; Trihas, N. The Influence of Social Media on the Travel Behavior of Greek Millennials (Gen Y). Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 8, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starcevic, S.; Konjikušić, S. Why Millennials as Digital Travelers Transformed Marketing Strategy in Tourism Industry; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kruczek, Z.; Szromek, A.; Walas, B.; Mazanek, L. Postawy i oczekiwania interesariuszy wobec zamiarów zrównoważenia turystyki w Krakowie po pandemii COVID-19. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Sklodowska Sect. B–Geogr. Geol. Mineral. Petrogr. 2021, 76, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development|UNWTO. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Chiu, A.S.F.; Aviso, K.B.; Baquillas, J.; Tan, R.R. Can Disruptive Events Trigger Transitions towards Sustainable Consumption? Clean. Responsible Consum. 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudjana, A.A.; Aini, S.N.; Nizar, H.K. Revenge tourism: Analisis minat wisatawan pasca pandemi COVID-19. Pringgitan 2021, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, T.-F.; Lin, X.; Yan, Y.-M. Explorsion of Current Situation and Marketing Suggestion after the Epidemic at Qionglu Scenic Area in Sichuan, China. Asian J. Lang. Lit. Cult. Stud. 2021, 4, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Starzyńska-Rosiecka, D. Badanie Kantar: 67 proc. Polaków jest Wdzięczna za Zdrowie Swojej Rodziny. Dz. Związkowy Pol. Dly. News 2021. Available online: https://dziennikzwiazkowy.com/spoleczenstwo/badanie-kantar-67-proc-polakow-jest-wdzieczna-za-zdrowie-swojej-rodziny/ (accessed on 18 September 2021).

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “War over Tourism”: Challenges to Sustainable Tourism in the Tourism Academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izurieta, G.; Torres, A.; Patiño, J.; Vasco, C.; Vasseur, L.; Reyes, H.; Torres, B. Exploring Community and Key Stakeholders’ Perception of Scientific Tourism as a Strategy to Achieve SDGs in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; Torres-Delgado, A.; Crabolu, G.; Martinez, J.P.; Kantenbacher, J.; Miller, G. The Impact of Sustainable Tourism Indicators on Destination Competitiveness: The European Tourism Indicator System. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, J.A.; Milano, C. Becoming Centre: Tourism Placemaking and Space Production in Two Neighborhoods in Barcelona. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart Tourism: Foundations and Developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jararweh, Y.; Otoum, S.; Ridhawi, I.A. Trustworthy and Sustainable Smart City Services at the Edge. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, T. Smart Technologies, Back-to-the-Village Rhetoric, and Tactical Urbanism: Post-COVID Planning Scenarios in Italy. Int. J. E-Plan. Res. IJEPR 2021, 10, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Amaranggana, A. Smart Tourism Destinations. In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014, Dublin, Ireland, 21–24 January 2014; Xiang, Z., Tussyadiah, I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Corte, V.; D’Andrea, C.; Savastano, I.; Zamparelli, P. Smart Cities and Destination Management: Impacts and Opportunities for Tourism Competitiveness. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 17, 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee, E.; Bertocchi, D. Finding Patterns in Urban Tourist Behaviour: A Social Network Analysis Approach Based on TripAdvisor Reviews. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2018, 20, 153–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotis, J.; Buhalis, D.; Rossides, N. Social Media Use and Impact during the Holiday Travel Planning Process. In Proceedings of the Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2012, Helsingborg, Sweden, 25–27 January 2012; Fuchs, M., Ricci, F., Cantoni, L., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2012; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for Sharing Tourism Experiences through Social Media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, M.T.; Sharmin, F.; Badulescu, A.; Gavrilut, D.; Xue, K. Social Media-Based Content towards Image Formation: A New Approach to the Selection of Sustainable Destinations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Ruiz, D.; Elizondo-Salto, A.; de la O. Barroso-González, M. Using Social Media in Tourist Sentiment Analysis: A Case Study of Andalusia during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Wang, S.; Gu, J. Public Participation in Smart-City Governance: A Qualitative Content Analysis of Public Comments in Urban China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Ruhanen, L.; Whitford, M. Indigenous Peoples and Tourism: The Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wijesinghe, S.N.R.; Mura, P.; Tavakoli, R. A Postcolonial Feminist Analysis of Official Tourism Representations of Sri Lanka on Instagram. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.X.; Wong, I.A. The Social Crisis Aftermath: Tourist Well-Being during the COVID-19 Outbreak. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 859–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltra González, I.; Camarero, C.; San José Cabezudo, R. SOS to My Followers! The Role of Marketing Communications in Reinforcing Online Travel Community Value during Times of Crisis. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Together in Travel. Available online: https://wttc.org/COVID-19/Together-In-Travel (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Rabbiosi, C. Renewing a Historical Legacy: Tourism, Leisure Shopping and Urban Branding in Paris. Cities 2015, 42, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Wang, S.; Liu, H. Understanding User Profiles on Social Media for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Multimedia Information Processing and Retrieval (MIPR), Miami, FL, USA, 10–12 April 2018; pp. 430–435. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, V.W.S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Exploring the Essence of Memorable Tourism Experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E.; Walejko, G. The Participation Divide: Content Creation and Sharing in the Digital Age. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2008, 11, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, S. Does Cultural Difference Matter on Social Media? An Examination of the Ethical Culture and Information Privacy Concerns. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, E.B. Gender Differences in Internet Use Patterns and Internet Application Preferences: A Two-Sample Comparison. CyberPsychology Behav. 2004, 3, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B. Are Information Quality and Source Credibility Really Important for Shared Content on Social Media? The Moderating Role of Gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 31, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, A.; Barron, P. Factors in the Provision of Engaging Experiences for the Traditionalist Market at Visitor Attractions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. The Relative Importance of Perceived Ease of Use in IS Adoption: A Study of E-Commerce Adoption. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 14, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Csobanka, Z.E. The Z Generation. Acta Technol. Dubnicae 2016, 6, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolot, A. The Characteristics of Generation Z. E-Mentor 2018, 74, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorowicz, J. The Situation of Generations on the Labour Market in Poland. Econ. Environ. Stud. 2018, 18, 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, P. Canada Digital Habits by Generation. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/canada-digital-habits-by-generation (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Karasek, A.; Hysa, B. Social Media and Generation Y, Z-a Challenge for Employers. Zesz. Nauk. Organ. Zarządzanie Politech. Śląska 2020, 3, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinger, E.; McCrindle, M. The ABC of XYZ-Mark McCrindle PDF.Pdf. In Understanding the Global Generations; McCrindle Research: Norwest, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, V. AARP 2021 Travel Trends: Boomers Plan to Travel. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/research/topics/life/info-2021/2021-travel-trends.html (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Levy, V. 2020 Travel Trends. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/research/topics/life/info-2019/2020-travel-trends.html (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Naidoo, P.; Ramseook-Munhurrun, P.; Seebaluck, N.V.; Janvier, S. Investigating the Motivation of Baby Boomers for Adventure Tourism. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 175, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fishman, A. What to Know about Travel Marketing across Generations Post-COVID-19|PhocusWire. Available online: https://www.phocuswire.com/post-covid-travel-marketing-by-generation (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Expedia Group Media Solutions Travel Marketing Across Generations in 2020: Reaching Gen Z, Gen X, Millennials, and Baby Boomers. Available online: https://skift.com/2019/12/11/travel-marketing-across-generations-in-2020-reaching-gen-z-gen-x-millennials-and-baby-boomers/ (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Vukic, M.; Kuzmanovic, M.; Stankovic, M.K. Understanding the Heterogeneity of Generation Y’s Preferences for Travelling: A Conjoint Analysis Approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk-Anioł, J. Tourism Trends among Generation Y in Poland. Turyzm 2012, 22, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dębski, M.; Krawczyk, A.; Dworak, D. Wzory zachowań turystycznych przedstawicieli Pokolenia Y. Stud. Pr. Kol. Zarządzania Finans. 2019, 172, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expedia Group Media, E.G.M. How Younger Generations Are Shaping the Future of Travel. Available online: https://info.advertising.expedia.com/multi-generational-custom-research-gen-z (accessed on 8 April 2021).

- Molinillo, S.; Anaya-Sánchez, R.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Smart City Communication via Social Media: Analysing Residents’ and Visitors’ Engagement. Cities 2019, 94, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Aranda, L.-A.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Bastidas-Manzano, A.-B. Tourism Research after the COVID-19 Outbreak: Insights for More Sustainable, Local and Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 73, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Vishik, C.; Rao, H.R. Privacy Preserving Actions of Older Adults on Social Media: Exploring the Behavior of Opting out of Information Sharing. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Schyff, K.; Flowerday, S.; Lowry, P.B. Information Privacy Behavior in the Use of Facebook Apps: A Personality-Based Vulnerability Assessment. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adjei, J.K.; Adams, S.; Mensah, I.K.; Tobbin, P.E.; Odei-Appiah, S. Digital Identity Management on Social Media: Exploring the Factors That Influence Personal Information Disclosure on Social Media. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Yilmaz, G.S.; Hirsch, N.; Khan, M.T.; Tang, M.; Tran, C.; Kanich, C.; Ur, B.; Zheleva, E. Moving Beyond Set-It-And-Forget-It Privacy Settings on Social Media. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 991–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Pensa, G.R.; Di Blasi, G. A Privacy Self-Assessment Framework for Online Social Networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 86, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presthus, W.; Vatne, D.M. A Survey on Facebook Users and Information Privacy. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 164, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane-Simpson, C.; Manago, A.; Gaggi, N.; Gillespie-Lynch, K. Why Do College Students Prefer Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram? Site Affordances, Tensions between Privacy and Self-Expression, and Implications for Social Capital. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosteller, J.; Poddar, A. To Share and Protect: Using Regulatory Focus Theory to Examine the Privacy Paradox of Consumers’ Social Media Engagement and Online Privacy Protection Behaviors. J. Interact. Mark. 2017, 39, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankton, K.N.; McKnight, D.H.; Tripp, F.J. Facebook Privacy Management Strategies: A Cluster Analysis of User Privacy Behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Ahmad, I.H. Information Privacy Concerns, Antecedents and Privacy Measure Use in Social Networking Sites: Evidence from Malaysia. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, H.; Chan, E.H.W. A Model to Measure Tourist Preference toward Scenic Spots Based on Social Media Data: A Case of Dapeng in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Kumar, S.; Hu, C. Gender Differences in Motivations for Identity Reconstruction on Social Network Sites. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2017, 34, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Generation | [%] | Gender | [%] |

| BB | 16.2% | Man | 44.6% |

| X | 32.5% | Woman | 55.4% |

| Y | 32.1% | ||

| Z | 19.2% | ||

| Level of education | [%] | Length of using SM | [%] |

| Basic/Junior high | 0.4% | Over 6 years | 70.8% |

| Secondary | 23.6% | From 4 to 6 years | 8.5% |

| Vocational | 0.4% | From 2 to 4 years | 4.8% |

| Higher I | 19.9% | Up to 2 years | 4.8% |

| Higher II | 52.0% | I do not remember | 10.0% |

| Postgraduate | 1.1% | Never used | 1.1% |

| PhD | 2.6% |

| Research Question | Questionnaire Questions | Response Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Research question no. 1 | I use social media during a tourist trip to: | Order scale (Likert): Strongly agree Agree I have no opinion Disagree Strongly disagree |

| Ongoing planning of further stages of a trip | ||

| Obtaining information about the place of stay | ||

| Commenting on events taking place in the place of stay | ||

| Making contact with the local community | ||

| Obtaining information about current events (cultural, entertainment, etc.) | ||

| Current sharing experiences from a tourist trip | ||

| Making contact with other tourists | ||

| Obtaining information about current difficulties (e.g., traffic jams, accidents) | ||

| Research question no. 2 | I use social media to share the experience of a travel trip by: | Order scale (Likert): Strongly agree Agree I have no opinion Disagree Strongly disagree |

| Sending email/text messages | ||

| Photo/video album for friends | ||

| Public photo/video album | ||

| Writing reviews | ||

| Posting statements and photos in social groups/ forums | ||

| Posting on blogs | ||

| Research question no. 3 | Please select which settings your profile has on the following social media: | Nominal scale: “Friends only” privacy settings I customise my privacy settings Public profile I do not know what my privacy settings are I do not have a profile |

| Blogs and microblogs | ||

| Social portals | ||

| Content communities | ||

| Rating portals | ||

| Travel forums |

| I Use SM for | Measure | BB | X | Y | Z | Kruskal–Wallis Test | Man | Woman | Mann–Whitney U Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ongoing planning of further stages of a trip | Mean | 0.05 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.032 | 0.44 | 0.72 | 0.021 |

| Med. | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.24 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 1.10 | |||

| Obtaining information about the place of stay | Mean | 0.39 | 0.86 | 1.02 | 1.10 | 0.008 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.005 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.26 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.94 | 1.00 | |||

| Commenting on events taking place in the place of stay | Mean | −0.28 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.35 | 0.280 | −0.09 | −0.14 | 0.733 |

| Med. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| SD | 1.26 | 1.29 | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.21 | 1.25 | |||

| Making contact with the local community | Mean | −0.49 | −0.30 | −0.12 | −0.40 | 0.290 | −0.33 | −0.27 | 0.627 |

| Med. | −1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.00 | −0.50 | 0.00 | |||

| SD | 1.20 | 1.21 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.15 | 1.24 | |||

| Obtaining information about current events (cultural, entertainment, etc.) | Mean | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 0.790 | 0.80 | 0.91 | 0.146 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.34 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.91 | 1.02 | |||

| Current sharing experiences from a tourist trip | Mean | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.110 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.931 |

| Med. | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 | |||

| SD | 1.35 | 1.35 | 1.25 | 1.09 | 1.22 | 1.33 | |||

| Making contact with other tourists | Mean | −0.37 | −0.36 | −0.21 | −0.50 | 0.570 | −0.30 | −0.38 | 0.554 |

| Med. | −1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| SD | 1.38 | 1.20 | 1.16 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 1.23 | |||

| Obtaining information about current difficulties (e.g., traffic jams, accidents) | Mean | 0.42 | 0.55 | 0.78 | 1.04 | 0.070 | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.423 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.42 | 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.82 | 1.13 | 1.13 |

| Measure | BB | X | Y | Z | Kruskal–Wallis Test | Man | Woman | Mann–Whitney U Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sending e-mail/text messages | Mean | 0.32 | −0.02 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.524 | −0.09 | 0.30 | 0.014 |

| Med. | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.51 | 1.45 | 1.24 | 1.28 | 1.31 | 1.38 | |||

| Photo/video album for friends | Mean | −0.41 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.008 | 0.10 | 0.23 | 0.389 |

| Med. | −1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.45 | 1.42 | 1.35 | 1.29 | 1.39 | 1.41 | |||

| Public photo/video album | Mean | −1.00 | −0.67 | −0.78 | −0.80 | 0.525 | −0.75 | −0.81 | 0.619 |

| Med. | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.10 | 1.25 | 1.28 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 1.23 | |||

| Writing reviews | Mean | −0.52 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.53 | 0.004 | −0.06 | −0.22 | 0.252 |

| Med. | −0.50 | 0.50 | 0.00 | −1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| SD | 1.27 | 1.25 | 1.23 | 1.22 | 1.27 | 1.26 | |||

| Posting statements and photos in social groups/forums | Mean | −0.32 | −0.01 | −0.07 | −0.24 | 0.546 | −0.23 | −0.04 | 0.262 |

| Med. | −1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| SD | 1.49 | 1.35 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 1.39 | |||

| Posting on blogs | Mean | −0.95 | −0.85 | −0.83 | −0.94 | 0.839 | −0.82 | −0.92 | 0.503 |

| Med. | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | −1.00 | |||

| SD | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.15 | 1.12 |

| Generation | Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Value of the Chi-Square Statistics | p-Value | The Value of the Chi-Square Statistics | p-Value | |

| Blogs and microblogs | 9.824 | 0.631 | 8.268 | 0.082 |

| Social portals | 81.727 | 0.000 | 5.745 | 0.219 |

| Content communities | 30.674 | 0.002 | 9.625 | 0.047 |

| Rating portals | 24.837 | 0.016 | 8.424 | 0.077 |

| Travel forums | 12.398 | 0.414 | 10.074 | 0.039 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hysa, B.; Zdonek, I.; Karasek, A. Social Media in Sustainable Tourism Recovery. Sustainability 2022, 14, 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020760

Hysa B, Zdonek I, Karasek A. Social Media in Sustainable Tourism Recovery. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020760

Chicago/Turabian StyleHysa, Beata, Iwona Zdonek, and Aneta Karasek. 2022. "Social Media in Sustainable Tourism Recovery" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020760

APA StyleHysa, B., Zdonek, I., & Karasek, A. (2022). Social Media in Sustainable Tourism Recovery. Sustainability, 14(2), 760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020760