Critical Junctures in Sustainable Social Housing Policy Development in Saudi Arabia: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Saudi Context and the Research Agenda

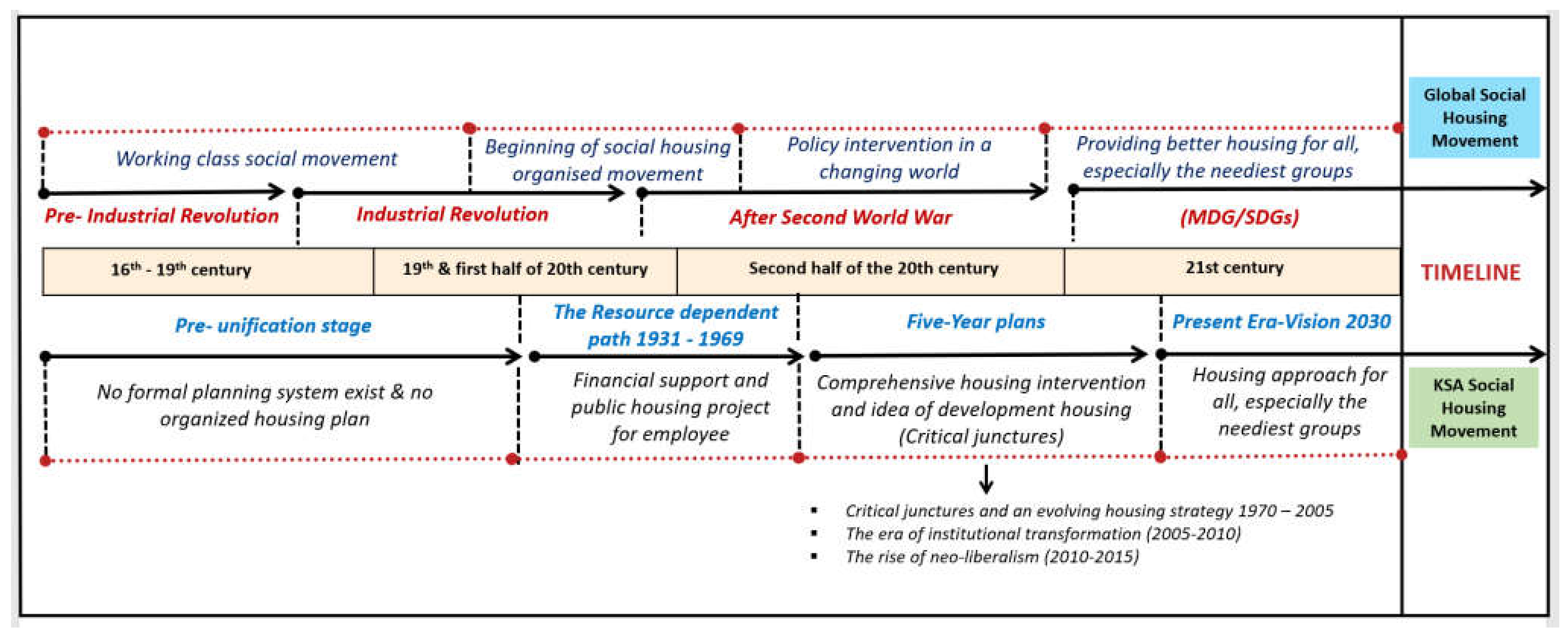

1.2. Literature on Historical Policy Development

2. Materials and Methods

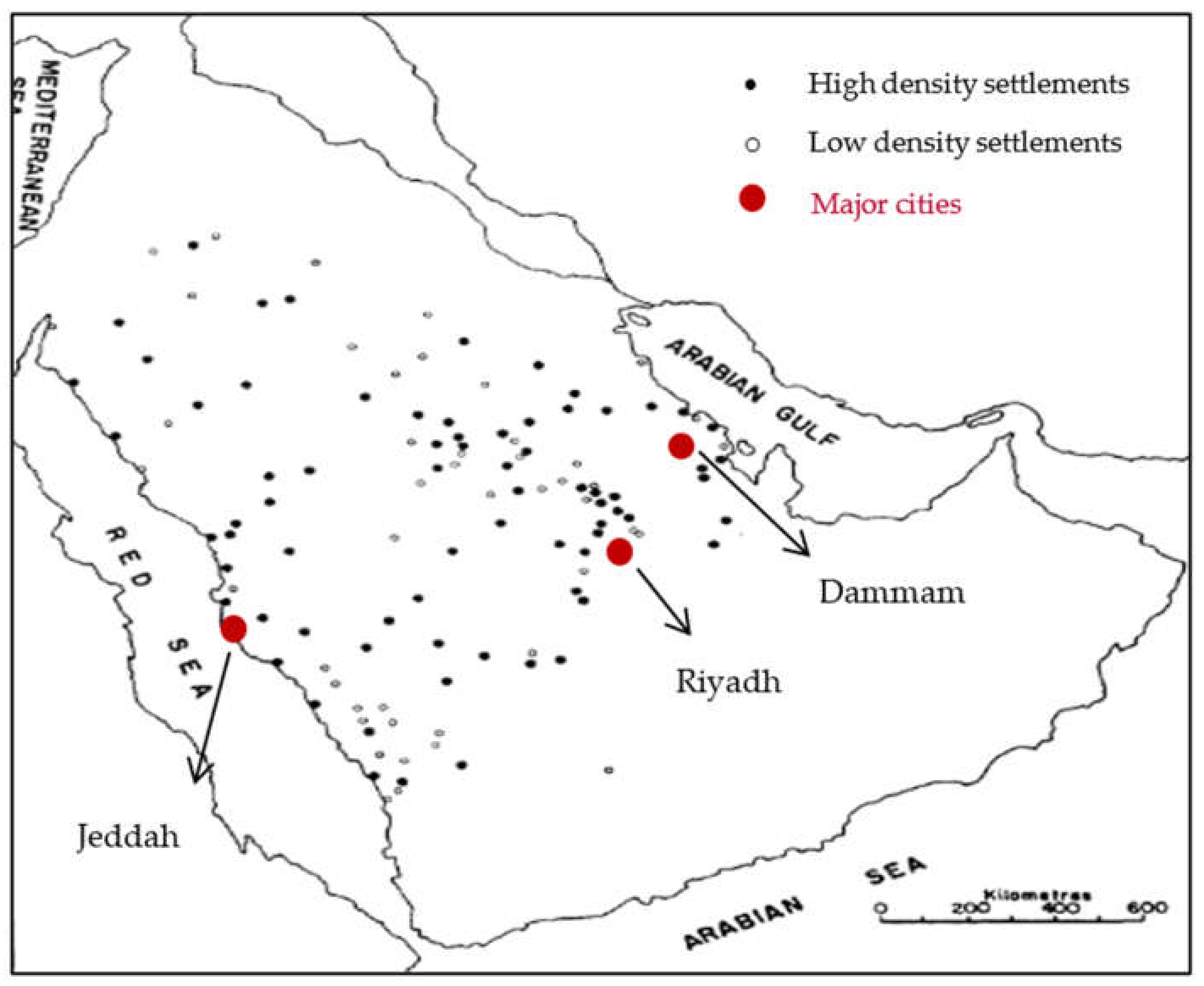

Study Area

3. Findings on the Social Housing Policy Development Process in the KSA

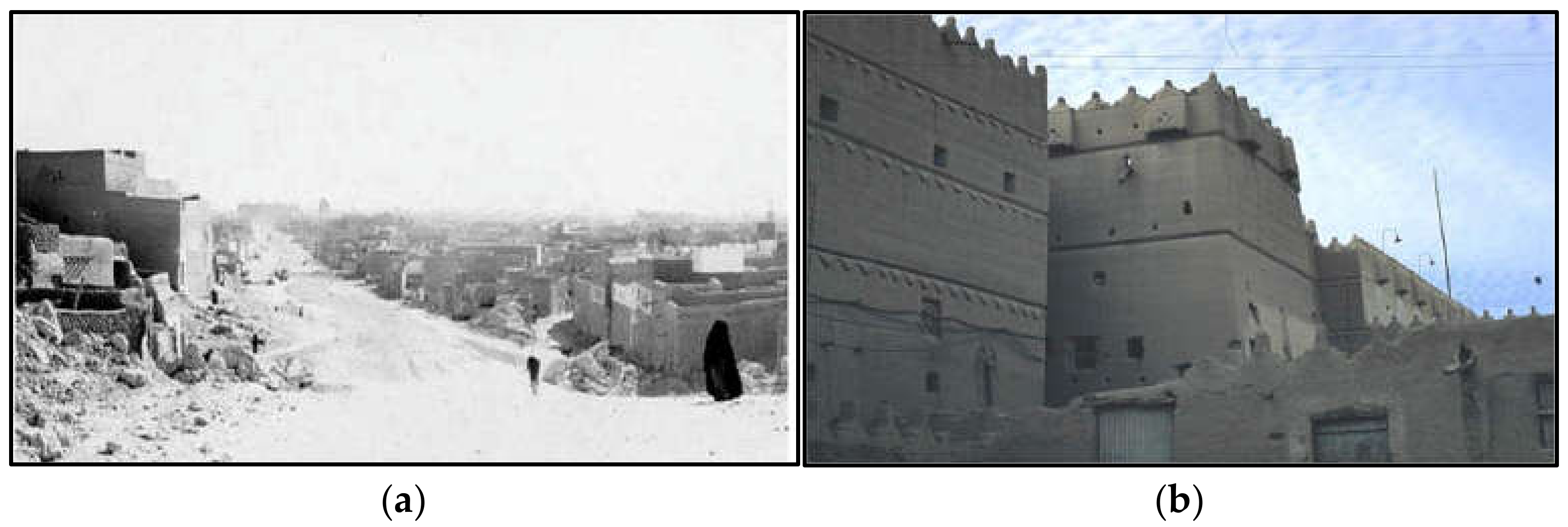

3.1. Pre-Unification Stage (Since 1930)

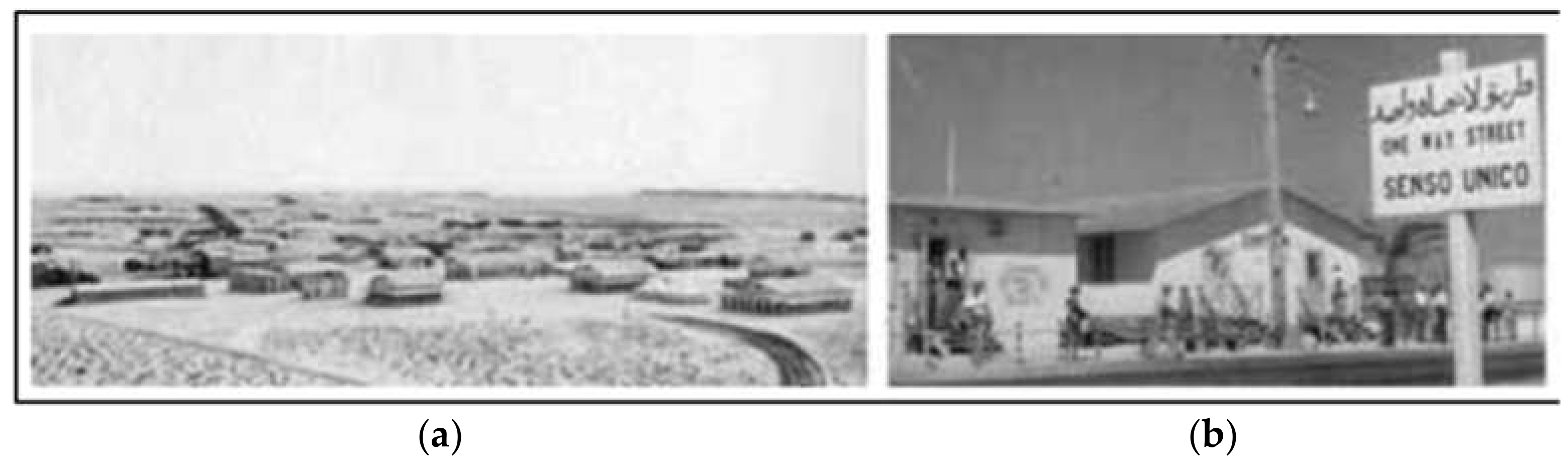

3.2. The Resource Dependent Path (1931–1969)

3.3. Critical Junctures and an Evolving Housing Strategy (1970–1995)

3.4. The Rise of Neo-Liberalism (1995–2005)

…central government regulations, which limit the number of years for amortizing mortgages on housing loans to seven years, have not been changed to accommodate the Plan’s promulgation. To date, banks are still not allowed to extend the time period of seven years. (p.9)

3.5. The Fall of Public Housing and Institutional Transformation (2005–2015)

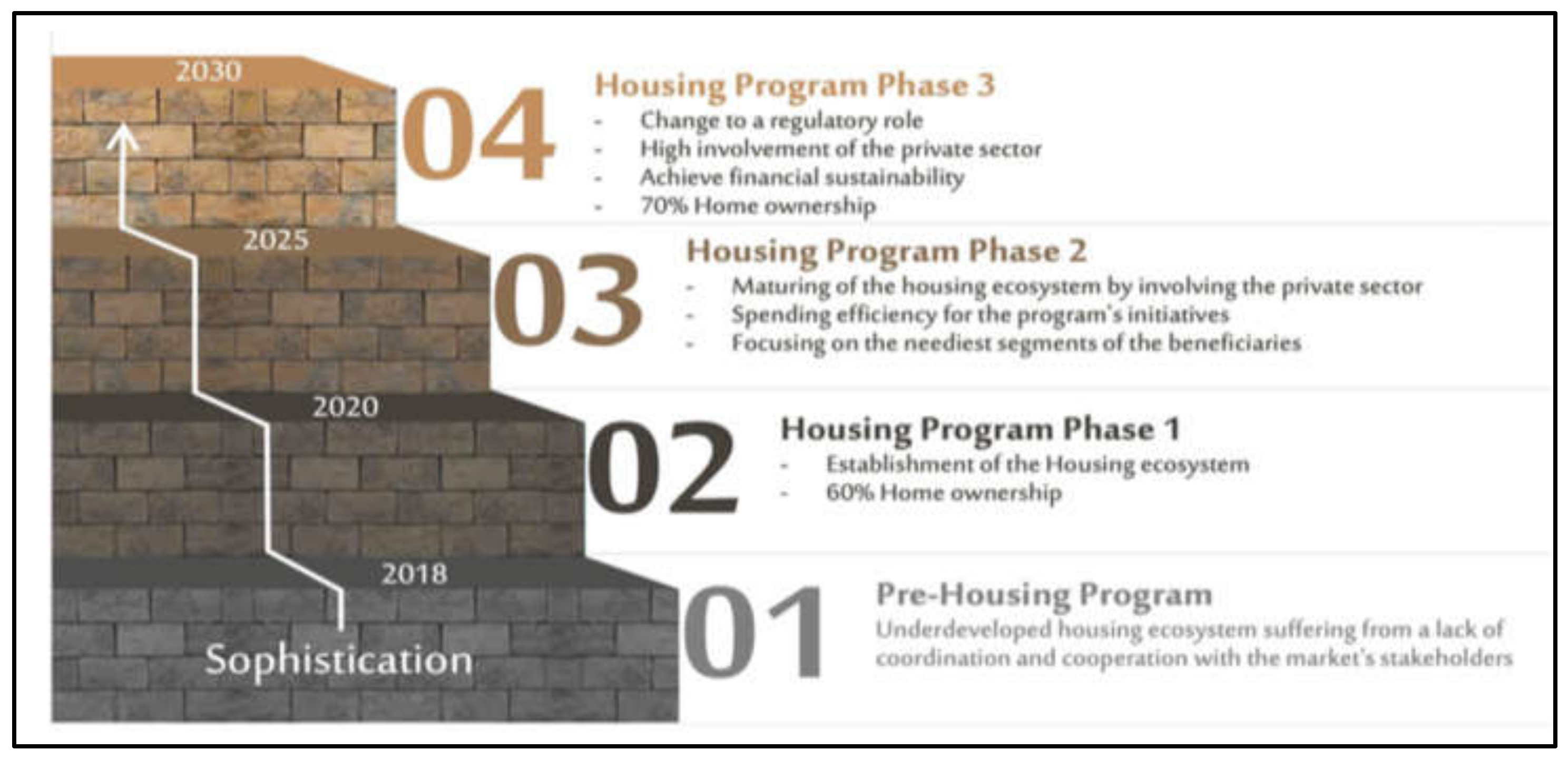

3.6. Vision 2030 (2016 Onward)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alqahtany, A. People’s perceptions of sustainable housing in developing countries: The case of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Hous. Care Support 2020, 23, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Urbanization. 2018. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Saldaña-Márquez, H.; Gómez-Soberón, J.M.; Arredondo-Rea, S.P.; Gámez-García, D.C.; Corral-Higuera, R. Sustainable social housing: The comparison of the Mexican funding program for housing solutions and building sustainability rating systems. Build. Environ. 2018, 133, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitlin, D.; Mogaladi, J. Social movements and the struggle for shelter: A case study of eThekwini (Durban). Prog. Plan. 2013, 84, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraatz, J.A.; Mitchell, J.; Matan, A.; Newman, P. Rethinking Social Housing: Efficient, Effective and Equitable. 2015. Sustainable Built Environment National Research Centre: Perth. Available online: https://sbenrc.com.au/app/uploads/2014/09/1.31-Industry_Progress-Report-1-FINAL-020315.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Vale, L.J.; Shamsuddin, S.; Gray, A.; Bertumen, K. What affordable housing should afford: Housing for resilient cities. Cityscape 2014, 16, 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kellett, R.; Christen, A.; Coops, N.C.; van der Laan, M.; Crawford, B.; Tooke, T.R.; Olchovski, I. A systems approach to carbon cycling and emissions modeling at an urban neighborhood scale. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 110, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraftab, F. Insurgent Planning: Situating Radical Planning in the Global South. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation Development Programme. Revision of World Urbanization Prospects; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Dynamics. 2018. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/ (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Woodcraft, S.; Hackett, T.; Caistor-Arendar, L. Design for Social Sustainability: A Framework for Creating Thriving New Communities; The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti, M. Sustainable Social Housing Initiative (SUSHI); United Nations Environment Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtany, A. Affordable housing in Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030: New developments and new challenges. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2021, 14, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttor, G. Canadian Social Housing: Policy Evolution and Impacts on the Housing System and Urban Space; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, K.; Arrigoitia, M.F.; Whitehead, C.M. Social housing in Europe. Eur. Policy Anal. 2015, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, D.; Scutella, R. What are the impacts of living in social housing? New evidence from Australia. Hous. Stud. 2019, 35, 612–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunstall, R.K.; Pleace, N. Social Housing: Evidence Review; University of York: York, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amirjani, R. Shushtar New Town: A Turning Point in Iranian Social Housing History; University of Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lévy-Vroelant, C.; Reinprecht, C.; Robertson, D.; Wassenberg, F. Learning from history: ‘Path dependency’ and change in the social housing sectors of Austria, France, the Netherlands and Scotland. In Social housing in Europe; LSE/Wiley: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Poggio, T.; Whitehead, C. Social Housing in Europe: Legacies, New Trends and the Crisis. Crit. Hous. Anal. 2017, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppercorn, I.; Taffin, C. Social housing in the USA and France: Lessons from convergences and divergences. Urban Plan. Int. 2009, 3, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gowan, P.; Cooper, R. Social Housing in the United States; People’s Policy Project: Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson, R.; Ellen, I.G.; Ludwig, J. Low-income housing policy. In Economics of Means-Tested Transfer Programs in the United States; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 59–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bratt, R.G. The Role of Nonprofits in Meeting the Housing Challenge in the United States. Urban Res. Pr. 2017, 12, 7–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoloff, J.A. A brief history of public housing. In Proceedings of the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 9 August 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tombs, R. The English and Their History; Penguin Books Limited: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, I. Hidden from History? Housing Studies, the Perpetual Present and the Case of Social Housing in Britain. Hous. Stud. 2006, 21, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D. Some Practical Difficulties of Implementing Social Mix. Hous. Res. Hous. Auth. 1979, 2, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Czischke, D.; Gruis, V. Managing Social Rental Housing in the EU in a Changing Policy Environment: Towards a Comparative Study. In Comparative Housing Policy; European Network for Housing Research: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pestoff, V. Co-production and Third Sector Social Services in Europe: Some Concepts and Evidence. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2012, 23, 1102–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, A. Neoliberalism and the concept of governance: Renewing with an older liberal tradition to legitimate the power of capital. Mémoire(s) Identité(s), Marg. Eacute(s) Dans Le Monde Occident. Contemp. 2015, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertz, G.; Kharas, H. Beyond Neoliberalism: Insights from Emerging Markets; Brookings Institution: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Topal, A. Global Processes and Local Consequences of Decentralization: A Sub-national Comparison in Mexico. Reg. Stud. 2013, 49, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, J.M.; Lidström, A. Decentralization, Local Government, and the Welfare State. Governance 2007, 20, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, R.A.; Abdul-Muhmin, A.G. Housing preferences and attribute importance among low-income consumers in Saudi Arabia. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M. Prospects for Land, Rent and Housing in UK Cities; Regional Studies Association: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Center for strategic prevention support. Implementing Promising Community Interventions. 2020. Available online: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/implement/changing-policies/overview/main (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Swapan, M.S.H.; Khan, S. From authoritarian transplantation to prescriptive imposition of good governance: Tracing the diffusion of western planning concepts in Bangladesh. Int. Plan. Stud. 2018, 23, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Vision 2030. “The Housing Vision Realization Program”. 2021. Available online: www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/programs/Housing (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Vision Realization Office. Initiatives Related to the Saudi Vision 2030 Realization Programs. 2021. Available online: www.housing.gov.sa/en/node/1949 (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Saudi Vision 2030. The Housing Program Delivery Plan (2021–2025). 2020. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/media/ek5al1pw/housing_eng.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Kılınç, K.; Gharipour, M. Social Housing in the Middle East: Architecture, Urban Development, and Transnational Modernity; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shiha, A.; Hariqi, F.; Slagur, J. Estimating the Number, Area and Type of Housing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for the Next Twenty Years; King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Elasrag, H. Affordable Housing in GCC Countries. 2016. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2711977 (accessed on 29 August 2021). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Choi, C.G.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Seong, E.Y. Critical junctures and path dependence in urban planning and housing policy: A review of greenbelts and New Towns in Korea’s Seoul metropolitan area. Land Use Policy 2019, 80, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capoccia, G.; Kelemen, R.D. The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism. World Politics 2007, 59, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J. The Critical Juncture Concept’s Evolving Capacity to Explain Policy Change. Eur. Policy Anal. 2019, 5, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, B.; Ruonavaara, H. Comparative Process Tracing in Housing Studies. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2011, 11, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K.; Manzi, T. ‘The party’s over’: Critical junctures, crises and the politics of housing policy. Hous. Stud. 2017, 32, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, R.B.; Collier, D. Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labour Movement and Regime Dynamics in Latin America; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, J. Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory Soc. 2000, 29, 507–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setterfield, M. Path Dependency. In SSRN 2663719. 2015. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2663719 (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Capoccia, G. Critical junctures and institutional change. Adv. Comp.-Hist. Anal. 2015, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipset, S.M.; Rokkan, S. Cleavage Structures, Party Systems and Voter Alignments: An Introduction; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schoultz, Å. Party Systems and Voter Alignments. In The Sage Handbook of Electoral Behaviour; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 30–55. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.A.; Schaffer, D. Learning from the Past—The History of Planning: Introduction. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1985, 51, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J. Analyzing Path Dependence: Lessons from the Social Sciences, in Understanding Change; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- David, P.A. Clio and the Economics of QWERTY. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Poku-Boansi, M. Path dependency in transport: A historical analysis of transport service delivery in Ghana. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2020, 8, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M. Path Dependence and Critical Junctures in Irish Rental Policy: From Dualist to Unitary Rental Markets? Hous. Stud. 2014, 29, 616–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dear, M.J. Postmodernism and Planning. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1986, 4, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, B.; Judd, B. A Framework for Evaluating Neighbourhood Renewal—Lessons Learned from New South Wales and South Australia; National Housing Conference: Brisbane, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Al Nasiri, N.K.M. Planning, Policy and Performance: An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Social Housing Policy of Oman. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. Housing Markets and Policy Design in the Gulf Region: Overture, in Housing Markets and Policy Design in the Gulf Region; Gulf Research Centre Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, A. Housing Affordability–A Key to Social Cohesion in the Arabian Gulf, in Housing Markets and Policy Design in the Gulf Region; Gulf Research Centre Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy & Planning. All Development Plans. 2010. Available online: https://mep.gov.sa/en/development-plans (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Al-Hathloul, S.; Edadan, N. Evolution of settlement pattern in Saudi Arabia: A historical analysis. Habitat Int. 1993, 17, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Ghazzeh, T.M. The art of architectural decoration in the traditional houses of Al-Alkhalaf, Saudi Arabia. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2001, 18, 156–177. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mayouf, A. Provision of public housing in Saudi Arabia: Past, current and future trends. Population 2011, 2004, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, K. MODA, Ministries & Other New Riyadh Buildings—Feb.–Jun. 1961. Wheeler, Keith Website: Keith’s Old Military Photos. 2005. Available online: http://www.wheelerfolk.org/military/album_index.htm (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Mubarak, F.A. Cultural Adaptation to Housing Needs: A Case Study. In IAHS Conference Proceedings; Citeseer: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Naim, M. Identity in transitional context: Open-ended local architecture in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Archit. Res. Archit. Res. 2008, 2, 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Alkadi, A.H. Affordable Housing Standards for Low-Income Communities in Saudi Arabia; King Faisal University: Hofuf, Saudi Arabia, 2005; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, M.S. Economic Diversification in Saudi Arabia: The Need for Improving Competitiveness for Sustainable Development. In The GCC Economies; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtany, A.; Mohanna, A.B. Housing challenges in Saudi Arabia: The shortage of suitable housing units for various socioeconomic segments of Saudi society. Hous. Care Support 2019, 22, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy and Planning. Third Development Plan, Progress During the Second Plan; 1981. Available online: https://www.mep.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/Pages/DocumentsDetails.aspx?FId=11f492f8-7112-401d-a400-058ed406c0d1 (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Alhowaish, A.K. Eighty years of urban growth and socioeconomic trends in Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Experts at the Council of Ministers. Rules, Regulations and Policies. In Basic Law of Governance 2020. Available online: https://laws.boe.gov.sa/BoeLaws/Laws/LawDetails/16b97fcb-4833-4f66-8531-a9a700f161b6/1 (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- Alasmari, F. An Institutional Analysis of State-Market Relations in the Saudi Arabian Housing System: A Case Study of Riyadh. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtany, A. Developing consensus-based measures for housing delivery in Dammam metropolitan area, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2019, 2019. 12, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Economy & Planning. Sixth Development Plan, Regional and Urban Development 1999. Available online: https://www.mep.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/Pages/DocumentsDetails.aspx?FId=341efc86-b012-4729-858f-66d4fd2bb984 (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Bahammam, A. Housing Development: The Homeless Hope, 1st ed.; Research and Information Center, King Saud University: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Economy & Planning. The Eighth Development Plan, Directions of the Eighth Development Plan. 2005. Available online: https://www.mep.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/Pages/DocumentsDetails.aspx?FId=59f4fd61-ff5f-490c-a503-cb84fb7c0830 (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- Ministry of Economy and Planning. Ninth Development Plan, Housing. 2010. Available online: https://www.mep.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/Pages/DocumentsDetails.aspx?FId=ccf45bb6-b5f5-45d5-b0f9-6aab8546f85e (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- United Nations. Social Housing in the Arab Region: An Overview of Policies for Low-Income Households’ Access to Adequate Housing; United Nations: Beirut, Lebanon, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolos, K.; Balasis, E.; Patsavos, N. Social Housing as a State-Funded Mega Project: A Case Study from Saudi Arabia. Archit. Media Politics Soc. 2018, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahammam, A. An approach to provide adequate housing in Saudi Arabia. J. Archit. Plan. 2018, 30, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Alhubashi, H.H.M. Housing Sector in Saudi Arabia: Preferences and Aspirations of Saudi Citizens in the Main Regions; UPCommons. Portal del Coneixement Obert de la UPC: Catalunya, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Housing. Developmental Housing.” Programs and Initiatives and Partnership with the Private Sector. 2019. Available online: https://www.housing.gov.sa/en (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Albassam, B.A. Economic diversification in Saudi Arabia: Myth or reality? Resour. Policy 2015, 44, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahammam, A. The Difficulty of Obtaining and Possessing a Dwelling in Light of the Recent Circumstances in Saudi Arabia. Soc. J. 2015, 9, 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanna, A.B.; Alqahtany, A. Identifying the preference of buyers of single-family homes in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2019, 13, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuwaikhat, H.M.; Mohammed, I. Sustainability Matters in National Development Visions—Evidence from Saudi Arabia’s Vision for 2030. Sustainability 2017, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A.A.; Elsegaey, I.; Khraif, R.; Al-Mutairi, A. Population distribution and household conditions in Saudi Arabia: Reflections from the 2010 Census. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Authority for Statistics in Saudi Arabia. Demography Survey; General Authority for Statistics: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Accommodation | Second Plan Target (Housing Units) | Second Plan Achievement (Housing Units) | Target Achievement Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent residences (Public sector) | 25,500 | 53,600 | 210 % |

| Permanent residences (Private sector) | 122,100 | 150,000 | 123% |

| Temporary housing for projects | 51,000 | 51,000 | 100% |

| Total | 198,600 | 254,600 | 113% |

| Housing Demand | Ninth Plan Target (Housing Units) * |

|---|---|

| New housing units for Saudis | 800,000 |

| New housing units for non-Saudis | 200,000 |

| Housing units to meet the demand carried forward from the Eighth Development Plan | 70,000 |

| Residential units required for replacement | 70,000 |

| 10% reserve units to ease rent inflation | 110,000 |

| Total | 1,250,000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Mulhim, K.A.M.; Swapan, M.S.H.; Khan, S. Critical Junctures in Sustainable Social Housing Policy Development in Saudi Arabia: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052979

Al Mulhim KAM, Swapan MSH, Khan S. Critical Junctures in Sustainable Social Housing Policy Development in Saudi Arabia: A Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052979

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Mulhim, Khalid Abdullah Mulhim, Mohammad Shahidul Hasan Swapan, and Shahed Khan. 2022. "Critical Junctures in Sustainable Social Housing Policy Development in Saudi Arabia: A Review" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052979

APA StyleAl Mulhim, K. A. M., Swapan, M. S. H., & Khan, S. (2022). Critical Junctures in Sustainable Social Housing Policy Development in Saudi Arabia: A Review. Sustainability, 14(5), 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052979