1. Introduction

When it comes to international development, financial sustainability has been a perennial problem [

1]. Development in today’s globalized world, by definition, has to do with aiding the low-income countries to escape poverty caused by a myriad of issues which tend to trap them in their current states. Therefore, sustainable and well-targeted financial support is needed to help them break out from the undesirable status quo. Among different areas of developmental support, securing sufficient financial resources is particularly significant in the health sector where people’s very lives are at stake [

2]. In tackling healthcare issues, the recent COVID-19 crisis was yet another reminder of how the health issue is globally intertwined, a vivid display of how policies at the national level have profound international implications [

3,

4].

In these tumultuous times, it is most appropriate to examine healthcare funding sustainability globally, including in Eurasia. Both rich and poor countries in this region have experienced a highly dynamic growth in the last two decades and are expected to continuously play a central role in the global society [

5]. The Republic of Korea (hereafter Korea), a country that quickly rose from one of the most impoverished nations to a solid middle-power country, is a point in case. Even in the Official Development Assistance (ODA) scene, upon joining the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) as the 24th member in 2010, contribution by Korea soared both institutionally and budget-wise: it enacted the Framework Act on International Development Cooperation that laid the foundation of Korea’s ODA vision and system, and devised the Mid-term Strategy for Development Cooperation and the Annual Implementation Plans since 2011 [

6]. Korea also has actively participated in global discussions on sustainable development, connecting developed and developing countries as a middle-power country, with its symbolic status of being the very first nation to transition from an aid recipient to a donor nation in OECD history.

In terms of the ODA budget, Korea’s aid grew substantially from KRW 1174 billion (USD984 million) in 2010 to KRW 3710 billion (USD3108 million) in 2021. Korea’s ODA/GNI (%) also increased from 0.12% in 2010 to 0.14% in 2020, although it has failed to reach the 0.20% ODA/GNI target by 2020. In 2022, Korea’s ODA budget is expected to rise by KRW 458 billion (USD384 million) and reach KRW 4168 billion (USD3492 million), which is a 12.3% increase from 2021. While the Committee for International Development and Cooperation (CIDC), the coordinating body on Korea’s ODA, stipulates that Korea’s bilateral and multilateral ODA will remain at around 75% and 25%, respectively, the share of bilateral aid in 2022 will be around 82%. As for multilateral aid, the total multilateral aid budget will reach KRW 741 billion (USD621 million) in 2022. Regionally, Korea’s first priority has always been Asia; around 37% of total bilateral ODA will be allocated to the region, with partner countries in Africa receiving around 20% in 2022 [

7].

The global COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of donors’ bilateral and multilateral contributions to developing countries in supporting their COVID-19 responses. In particular, multilateral institutions in global health security, such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), have made great contributions to ensuring equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines globally. While Korea has made pledges to these global health initiatives through an innovative development finance mechanism called the Global Disease Eradication Fund (hereafter GDEF), which has been a distinguishing feature of Korea’s ODA policies, the absolute size of its contribution has still been small compared to other DAC member countries.

Thus, the main objective of this research is to review innovative development finance and examine the implementation in Korea, along with deriving future policy implications for global sustainability. To this aim, we conducted the first-ever set of stakeholder surveys specifically focused on Korea’s health aid and multilateral assistance to global health initiatives, which reveals the uniqueness of Korean public opinion on ODA. Based on the insights drawn from the survey, we provide relevant policy recommendations for Korea—and implicitly for many other nations in the Eurasia region—to enhance global health security and sustainability.

2. Background

2.1. Air Ticket Solidarity Levy as Innovative Development Finance (IDF)

In ODA, the importance of financial sustainability has been widely recognized. Although financial resources used for overseas aids should ideally be predictable, countries often vary their support for other countries at their whim, based on changing political priorities, popular sentiment and their own financial situations. For example, Yoon (2007) points out that the volatility of ODA was four times higher than the changes in Gross National Product (GNP) of developing countries [

8]. This inherent precariousness calls for a more stable and apolitical funding sources in order for health ODA to be maximally effective.

Reflecting this need, innovative development finance emerged as a supplemental source of funding to solve the global health problem. Among many types of non-traditional development finance methods suggested, imposing levies on air travel is considered to be the most successful and effective thus far [

9]. The levy system was a major topic at the International Conference on Financing for Development which resulted in the Monterrey Consensus in 2002 [

10]. Three years later, the UN adopted the ‘Declaration on Innovative Sources of Financing for Development’ where the support for the solidarity levy on airline tickets was officialized, strongly backed by Brazil, France, Germany and Chile. Thus, the funds raised were to be used towards sustainable global development, especially combatting global diseases such as HIV/AIDS and other pandemics [

11]. In 2006, the ‘Leading Group on Solidarity Levies to Fund Development (renamed the Leading Group on Innovative Financing for Development in May 2009)’ was formed. In order to effectively use the contributions made for health sector development, the nations that participated founded the International Finance Facility for Immunization (IFFIm) and Unitaid, the ‘International Drug Purchasing Facility’ [

12]. As could be seen from here, innovative development finance has had a strong focus on the health sector from its inception.

Under this innovative finance scheme, money is raised by a small contribution imposed on airfare. The airline industry was chosen to be the funding source for several reasons. First, the industry, and particularly ticket sales for overseas travels, has undoubtedly been one of the greatest beneficiaries of globalization. Second, securing finances from airline travels was thought to be a more stable and predictable method when compared to the decisions from political leaders. Third, adding a small sum to the tickets issued was technologically simple, feasible and low cost. Lastly, the overarching goal of fighting global poverty and hunger is in line with the interests of the global airline industry, since doing so will be conducive for its own long-term growth [

13,

14,

15].

More specifically on the funding mechanism, this policy mandates travelers leaving from participating nations to contribute when they pay for their airplane tickets to mostly foreign, but sometimes including domestic destinations. The exact amount to be paid as well as how to differentiate the payment across various classes of seats were left up to each nation to determine. It was understood that the payment imposed should be such that will not disrupt international air travels or the tourism industry. In addition, participation of each country should be in line with its national legislation and in accordance with international coordination.

France, which was among the first two countries along with Brazil that proposed this system, implemented it for the first time in July 2006 with strong support from the then President Jacques Chirac. Based on the Landau report commissioned by Chirac, the French government concluded taxing airline tickets had many merits, such as being able to target those who are affluent and having the airline industry—which stands for globalization—share the burden for global issues [

15]. The fund was to strengthen the health system and eradicate diseases in partner countries. The exact amount charged per ticket differs across countries. For French domestic flights, it is one euro for economy class and ten euros for first class; for international flights, the corresponding amount is four euros and forty euros. Other countries that adopted this solidarity tax soon after France were Brazil, Chile, Norway and the U.K. Currently, it is operating in nine countries including Korea, where the tax was introduced in 2007 [

14].

The effectiveness of this airline solidarity levy is demonstrated by many examples. For one, more than USD1 billion raised by this levy alone goes to the international drug facility operated by Unitaid annually. The strong purchasing power thus bestowed to Unitaid enables it to command 25 to 50 percent price discount for drugs in the pharmaceutical market [

16]. Furthermore, research supports that the levy does not negatively impact international air travels nor the profitability of the airline industry [

9,

15]. Given its effectiveness and minimal side effects, airline taxes are regarded as a promising source of sustainable funding for health sector development. The predictability that this type of funding scheme helps both donor and recipient nations to plan health activities well into the future, reducing supply and demand uncertainties. Gartner (2015), in his comparison of innovative development finance mechanisms, argues that “the airline ticket tax, which Unitaid utilized, appears to be the most sustainable” [

15] (p. 510), as the funding comes from consumer transactions at the individual level. In the time of the budget constraints faced by most national governments around the world [

17], this type of alternative approach can be especially valuable.

2.2. Korea’s Health ODA and GDEF

Health has been a principal sector in Korea’s ODA [

18]. In 2022, it will be the top priority sector in Korea’s ODA and previously, health has been the second largest sector in ODA after transportation. The health sector has received more than 10% of total bilateral ODA and with COVID-19, it was announced that health ODA will increase by 37%, from KRW 336 billion (USD282 million) in 2021 to KRW 458 billion (USD384 million) in 2022 [

19]. Korea’s bilateral health ODA is primarily concentrated in Asia and Africa [

15] and such regional focus can be explained by the government’s prioritization of Asia, followed by Africa. For instance, Korea will allocate 37.2% of bilateral ODA to Asia and 19.6% to Africa in 2022 [

19]. In addition to the bilateral aid, the Korean government pledged USD200 million to COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC) in 2021–2022 to improve developing countries’ access to COVID-19 vaccines.

When it comes to Korea’s contributions to the global health initiative—including CEPI, Gavi, Global Fund and Unitaid—GDEF plays a central role. As an emerging donor still struggling to meet the promised quota spent on ODA, GDEF has had a positive influence in Korea’s aid policies which is largely considered to be a success thanks to its effectiveness. Korea, as a member of the ‘Leading Group on Solidarity Levies to Fund Development’ from 2006, introduced the airfare levy in 2007 as the Global Poverty Eradication Contribution (GPEC). It was a deliberate endeavor to secure ‘innovative resources’ for development [

13], a novel initiative for Korea. Afterwards, the government took steps to amend the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) Act in order to formally introduce the international air ticket solidarity contribution solely aimed to combat poverty and disease mainly in Africa.

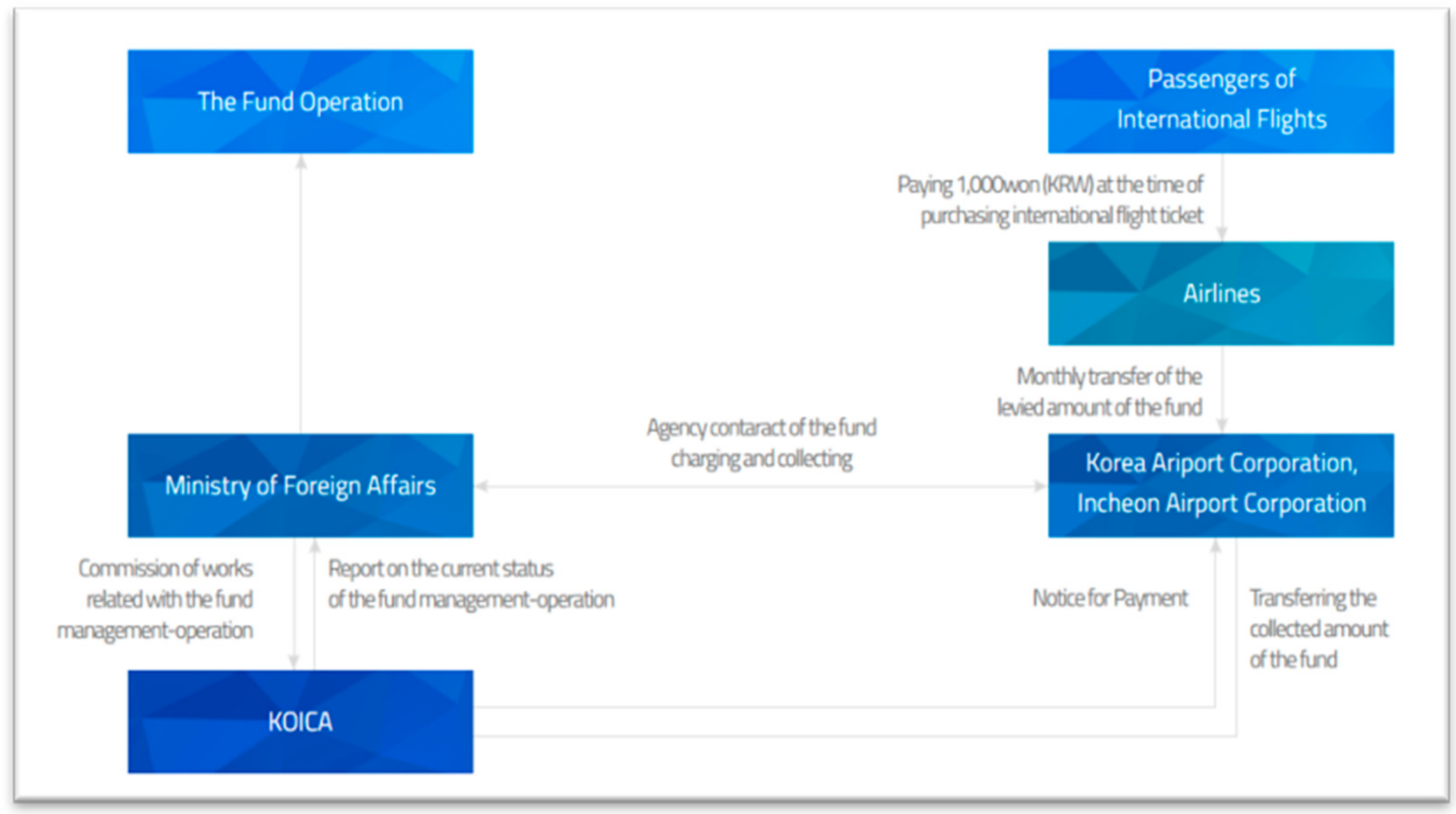

Under this measure, the government started to impose KRW 1000 (equivalent to USD1) on each departing international air ticket to fund GPEC. While the foreign minister is in charge of GPEC, KOICA would be entrusted by the said minister to manage and operate the contributions. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also set up the ‘Deliberate Committee on the Operation of the International Contributions for the Eradication of Poverty’ to handle the contributions. Although GPEC was initially intended to last for five years only, the five-year extension bill passed the National Assembly in 2012, and it eventually became a permanent fund from January 2017. At this time, GPEC was renamed to GDEF in accordance with the Act and Enforcement Decree on the Global Disease Eradication Fund [

20].

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of finances via multiple agencies.

The key objectives of GDEF as articulated in the GDEF strategy for 2017–2021 maintain the same spirit as before: to eradicate infectious disease in developing countries, to strengthen partner countries’ capacity for healthcare and medical services and to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 on good health and well-being. In particular, GDEF was designed to focus on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, waterborne diseases and neglected tropical diseases [

21].

Concerning implementation, GDEF utilizes the following programs: (1) public–private partnership programs with Korean non-governmental organizations (NGOs), (2) partnership with international organizations such as the WHO, UNICEF and IVI, and (3) the global partnership program which refers to contributions to global health initiatives such as Gavi and the Global Fund. Out of the three, contributions to global health initiatives come from the global partnership program. As of 2021, Korea supports the following four multilateral health funds: CEPI, Gavi, Global Fund and Unitaid.

Table 1 shows the latest contributions to the aforementioned four multilateral health initiatives by the Korean government. Funding for these initiatives is also allocated in line with GDEF’s overall objectives. That is, the Korean government supports the initiatives that focus on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, as well as those that increase the capacity of infectious disease prevention in partner countries.

GDEF is funded through three sources; other than the international departure fees from the plane tickets, government contributions and earnings from operating GDEF are also important parts of the fund. In turn, GDEF is used to complement existing ODA to support the three programs mentioned above. Although the government does not disclose exactly how much of the GDEF budget is allocated across the three programs, respectively, in terms of proportion, 37% of the budget for 2013–2017 went to the global partnership program, 24% to the partnership program with international organizations and 12% to the public–private partnership (PPP) program with Korean NGOs [

22]. Below is the comprehensive list of global health initiatives that Korea funds through GDEF with the amount given. All the grants are provided as unearmarked contributions.

2.3. Prior Literature and Existing Surveys

The literature on expert as well as public opinion on Korea’s foreign aid is quite thin. This limited pool of research can be divided into two categories: periodic opinion surveys conducted by the government and academic literature that analyses public or expert opinion on ODA. Additionally, as previously mentioned, prior research is virtually non-existent on understanding experts and/or public opinion on sectoral aid, such as Korea’s health ODA.

In terms of the government survey directed to the public, it was as late as 2011 that the Korean government first conducted a public awareness survey on general ODA to gauge the opinion of Korean citizens regarding the ODA policies in Korea. This was due to the government recognizing the need to secure public support in order to further increase the ODA budget and eventually raise them up to be partners in ODA. Since 2011, with this aim in mind, the public awareness survey has been conducted every year except in 2018.

Accordingly, academic literature analyzing public opinion on Korea’s ODA is in a fledgling state. Koo et al. (2018) investigated factors affecting Korean individuals’ support for its ODA using a quantitative methodology [

23]. Their results indicated that the respondents’ political outlook, awareness for human rights and favorable views on charity were key factors determining support for foreign aid. Such findings are partially related to the 2019 public survey results where 77.4% of those who oppose providing ODA also tended not to donate, but little difference on support for ODA was found by political agenda [

24]. Kim and Kalinowski (2020) tried to identify the reasons for the gap between the public’s sparse ODA knowledge yet high public support for ODA in Korea [

25]. Their conclusion is that it is due to Korea’s transition from a recipient to donor country, government-centered decision-making process with limited participation of civil society and aid propaganda-dominating dissemination of information. These findings are also consistent with the government survey in which 42.5% respondents in 2019 chose the reason for supporting ODA as ‘because Korea was a beneficiary to other countries’ assistance before’ [

24].

Experts, by definition, are knowledgeable in their field of survey. Expert surveys are useful in providing more clarity in uncertain phenomena, forecasting future events, integrating or interpreting existing data and determining what is known at present [

26]. In addition, experts’ opinions can paint a general picture of the experts’ knowledge at the time of the response [

27]. While the experts may hold different opinions due to their knowledge, learning and access to information, they ‘reflect most-up-to-date consensus on core assumptions’ [

28]. Additionally, experts tend to have less bias and overconfidence issues than non-experts in their answers, particularly on the state of the field, problem solving and assessing their own accuracy [

27].

Recognizing the need for a survey solely targeting experts, the Korean government initiated the ODA Satisfaction Survey for Experts in 2017, which was the first survey of its kind. Implemented from 2017 and 2019, the survey was designed to measure various aspects of satisfaction and perception of Korean ODA policies by professionals recruited from all across the board. To be exact, their expertise encompassed a total of 11 sectors of which public health/medicine comprised just a small part.

Therefore, given its significance and relevance to today’s world, we believe that a separate expert survey focused on health issues is warranted. Indeed, it is a curious omission that analyses of experts’ opinions have been conducted on other topics but not on health. For example, Park and Kim (2016) completed research on what experts thought about tourism, Song et al. (2021) about the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation and Lee and Park (2016) dealt with Korea’s aid architecture [

29,

30,

31]. However, there does not seem to be any similar studies examining health ODA specifically.

Another compelling reason for conducting a survey exclusively for health professionals is that existing expert surveys do suggest that health professionals are a unique group [

32,

33]. First, health professionals systematically differed from other groups in that they repetitively emphasized more ‘selfless’ reasons over the practical ones when asked why ODA is needed. Parallel tendencies were evident in their ODA policy priorities as well, as they chose the development of global professionals as the top ODA policy priority over more pragmatic concerns. Second, perhaps unsurprisingly, the majority of the health professionals picked public health and medicine as the most optimal sector of Korean ODA. However, the general public ranked the health sector as the fourth most important, which shows that there is a significant cognitive gap between experts and the public regarding this issue. Lastly, health experts consistently exhibited lower levels of satisfaction regarding ODA policies by Korea vis-à-vis experts in other domains, suggesting that health ODA may be confronted with a distinctive set of challenges.

With the above considerations in mind, we created and implemented a first-ever survey targeting those with expertise on Korean health ODA, who are expected to provide pointed and insightful answers on the most pressing health issues in today’s world.

3. Materials and Methods

The survey in this study is designed to reflect the status of knowledge and opinions on Korea’s ODA by the experts. Thus, the respondents were limited to those who are engaged in the international development cooperation field with a sound understanding of and experience in Korea’s ODA, including health aid. Naturally, these elites, referring to the active members in government and academia, have a significantly higher awareness of ODA than the public [

34]. Since this study asked specific questions on Korea’s health ODA, in particular its engagement with the global health initiatives, the authors deemed it more suitable to target the set of experts identified based on their years of experience, affiliation and background. Some respondents were directly involved with the decision-making process of Korea’s ODA policies and strategies by being members of the relevant bodies.

Two rounds of surveys were conducted for this research: one in March and the other in October of 2020. We contacted Korean stakeholders on Korea’s ODA and GDEF, with 13 people participating in the first round and 40 people in the second round of the survey. In total, 13 out of 20 people and 40 out of 68 people accepting the participation requested in the first and second rounds, respectively, which brought the response rate to 60 percent. There were no systematic differences across respondents and non-respondents in terms of their visible characteristics, such as gender, age, committee affiliations and areas of expertise. Details of the respondents are given in

Table 2.

The survey consisted of 20 questions on two major issues of Korea’s health ODA and GDEF. We decided to dedicate a significant portion of the survey to GDEF as it is not only a staple feature of Korean health ODA, but also a very effective funding scheme with important implications in financial sustainability. Questions 1 to 7 asked for participants’ perspectives on the priority, role and future direction of Korea’s health aid. Questions 8 to 19 concerned the participants’ knowledge and the future direction of GDEF and other global health initiatives. As for the format, some questions required the participants to choose their answer out of five options ranging from option 1 through to 5, which corresponded to ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘strongly agree’. Others asked the respondents to prioritize the different options provided, or to write one’s opinions without any word limits. The English version of the complete questionnaire is provided in the

Supplementary Materials.

4. Results

Survey questions 1 to 7 dealt with how the respondents perceived different aspects of the overall direction of health ODA by Korea. The first question was ranking the priority sectors of Korea’s ODA from first to third, out of eight sectors. Public health was chosen as the top area to focus, closely followed by education and then public administration. Question 2 requested the experts to grade the importance of health area in overall Korean ODA. Most respondents affirmed that public health was either “important” or “the most important”, reflecting their strong interest and commitment to health issues. Question 3 was a two-tiered question: it first asked if Korea should keep its direction of health ODA, and for either answer, to state how it should proceed in the future. It turned out that the survey participants were quite satisfied with the current direction of health ODA by the Korean government. For those who answered negatively, most of their ideas for improvement could be summed up in three themes: building a more comprehensive medical system and refining medical training in developing countries, as well as properly handling recent COVID-19 concerns.

Question 4 had the experts write three agendas that Korean health ODA must focus on institutionally; the responses to this will be explained in detail in

Section 5. In the following question, respondents were requested to clarify the reasons behind the Korean government’s engagement in health ODA. Their answers reaffirmed the known tendencies of the health professionals in Korea, which is to resonate deeply with the high-level causes of health sector development rather than being driven by more practical goals. Question 6 asked the experts what they thought the most serious public health problem was in developing countries. The two most common issues brought up were the lack of medical facilities and qualified medical personnel, and the unique vulnerabilities women and children face. Question 7 had the respondents freely express the ways to better direct and enhance the effectiveness of Korea’s health ODA, which answers will also be discussed thoroughly in

Section 5.

Survey questions 8 to 19 were about the respondents’ perspectives on GDEF and other global health initiatives. Question 8 asked whether survey participants were aware of GDEF, to which most replied positively. We then posed a question on which among the three types of partnerships the Korean government should prioritize: public–private partnership (PPP), partnership with international organizations or partnership with global health initiatives. Respondents viewed PPP as the most important, and partnerships with global health initiatives to be the least desirable. Question 10 was the same as Question 9, except that which among the three should be expanded under GDEF. Consistent with the previous question, PPP was the top choice by the experts.

Question 11 asked people to mention which additional diseases GDEF should target, and the most popular answer to this was the novel types of globally infectious diseases. In Question 12, we inquired how knowledgeable the respondents were on the major beneficiaries of GDEF. On average, respondents were most familiar with UNICEF and had a solid understanding of Gavi and the Global Fund, but were relatively unaware of GPEI, GFF and CEPI. Question 13 was on which of the global health initiatives the Korean government should be focusing on. Among the six choices given, Gavi was chosen as the top priority, followed by the Global Fund. The following question asked if the respondents could think of any further health issues that GDEF’s global partnership program should concentrate on. Similar to Question 11, the majority answer was to prioritize new infectious diseases that pose threats to global health security, such as COVID-19.

Question 15 on the fee increase for airplane tickets, and Questions 16 to 17 on raising public awareness are well elaborated in

Section 5. In Question 18, respondents were asked if the public support will increase in support for health ODA, for contributions to multilateral health organizations and for an increase in GDEF fees for all seat classes. Out of the three, experts thought public support will be strongest for overall health ODA, somewhat strong for multilateral health organizations and rather muted for the GDEF fee increase. The following question was if respondents thought COVID-19 would reduce the GDEF budget, to which the absolute majority answered positively, at least in the short run. Lastly, Question 20 requested the survey participants to freely provide their opinions on Korea’s global health aid. The answers included issues that varied widely, such as framing GDEF’s goals and objectives concretely, better participation of Korean stakeholders on multi-bi health aid, prioritization of partner countries’ development strategies, cooperation with diverse stakeholders, capacity building of Korea’s health ODA stakeholders and providing information on effective GDEF projects.

5. Discussion

In this section, we will highlight a few noteworthy findings on Korea’s health ODA in general first, which explains the context for the discussion that comes next. In

Section 5.2 and

Section 5.3 that follow, we summarize relevant survey materials and derive important lessons regarding innovative development finance.

Section 5.4 concludes with concrete policy implications derived from the findings from the study.

5.1. General Issues

What first stood out from our survey results was the respondents’ high satisfaction with the current overall direction of health ODA (Q. 3-1); 42 out of 53 voted to keep it rather than change it. At first glance, this seems to be in direct contrast to how unsatisfied health professionals were compared to other domains in the previous expert surveys, as mentioned in

Section 2.3. However, this particular response could have been partly influenced by the previous question, which was to grade the importance of the health area in Korean ODA on a scale of 1 (least important) to 5 (the most important). To this, the absolute majority answered that the Korean government took health quite seriously, with a total of 45 out of 53 respondents affirming that public health was either ‘important’ or ‘the most important’. Therefore, it is reasonable to interpret that the survey participants had thought that ‘keeping the current overall direction’ in the question that immediately followed also entailed Korea’s strong commitment to this sector. This interpretation is later confirmed by how vocal the respondents were when they were given opportunities to comment on how various aspects of Korea’s health ODA could improve.

Specifically, the overall problems of health ODA by the Korean government that repeatedly came up from the responses can be summarized by three topics: its fragmented and unsystematic nature, lack of capacity building and low public awareness.

First, when the experts were asked to freely write down three agendas that health ODA in Korea must focus on immediately (Q. 4), the two most popular answers were to reduce policy fragmentation (46 times) and to introduce an extensive health strategy (26 times). Both of these responses address the need for the Korean government to take a more holistic view on health ODA so that individual health-related policies can create synergy with various areas in foreign aid. A strong consensus has arisen among the stakeholders regarding the urgency for Korean policymakers to adopt this more sophisticated perspective. The above numbers reflect only those who explicitly mentioned the relevant terms as an answer to Question 4, but nearly all the experts participating in the survey expressed this idea in one way or another in the course of completing the survey. For example, when experts were asked how to enhance the effectiveness of health ODA in Question 7, the keyword that most frequently emerged was cooperation (24 times in total). More specifically, respondents argued that further cooperation is required with the following counterparts: global institutions (seven times), other domestic projects/institutions (seven times) and private firms (four times). Additionally, nine respondents mentioned that the most immediate focus should be to institute a holistic health ODA strategy. This again shows how they think a systematic and comprehensive strategy at the governmental level is presently lacking. In sum, respondents were most hoping to see future Korean health ODA build on strong cooperative relationships domestically and internationally, with an orderly strategy in place.

Second, many respondents called for stronger capacity building as Korea engages in health ODA for developing countries. Interestingly, quite a few people addressed the need to strengthen the developmental capacity on the Korean side rather than the partner countries. For example, 15 people touched upon the theme of capacity building when asked how to make health ODA more effective (Q. 7), and 9 people talked about raising capable professionals in Korea. This attests to the present dearth of qualified manpower in Korea, especially those who possess a professional understanding of both the medical and developmental domains. We can catch a glimpse of where the concrete problem lies through the minority group who dissented from Korea continuing its current direction of health ODA (Q. 3-1). Out of 11 who vetoed, 4 people pointedly opposed the way medical training programs are conducted. According to the dissents, the programs currently offered are ineffective since they are based narrowly on Korean experiences or used as a political tool. These concerns expose Korea’s relative lack of accumulated past learning in the developmental scene as a nascent donor, failing to achieve a sustainable impact in the partner nations.

Lastly, quite a few participants believed that there was a need to further enlighten the public on Korea’s health ODA efforts. Questions 16 and 17 asked if there is a need to raise public awareness on global health initiatives and if so, why. Responding to these, experts agreed by and large that the present level of public awareness is insufficient, with 17 people pointing out that the Korean public simply does not have enough knowledge on the country’s global health initiatives. Although the aforementioned public awareness surveys conducted by the government indicated that most people have basic knowledge of Korea offering overseas aid, most of them in fact lack an in-depth understanding unless they were predisposed to take a special interest in foreign aid. Additionally, 14 people mentioned that better awareness on health ODA would help garner public support since the consent of the public is needed for ODA budget increases. This would be particularly true for funding schemes such as GDEF, as the resources come directly from the public. Additionally, five people noted that informing the public of global health initiatives’ work and their impact can help restore public trust, which is somewhat diminished in the COVID-19 period due to the WHO’s initial missteps in dealing with the pandemic [

35].

5.2. GDEF

To start, there was a solid understanding of the purpose and programs of GDEF among ODA stakeholders in Korea. When asked how well they know GDEF (Q. 8), a total of 39 people noted that they knew it well or very well. Considering how GDEF has been a unique element in Korea’s foreign aid policies, it is a somewhat expected result that most of the experts were familiar with this form of innovative development finance.

In general, the respondents strongly supported increasing the fee from the current level imposed on international air flights, especially raising it to the maximum amount possible (around USD8–10) for business class and above. As explained in

Section 2.2, GDEF is largely based on an air ticket solidarity levy system and the Korean government currently charges KRW 1000 (USD1) on each departing international air ticket. However, under the current law, the foreign minister may differentially impose fees on persons boarding a higher seat class within the scope of KRW 10,000 (USD10). Given this background, Question 15 asked stakeholders’ views on the proper amount of fee to be charged for the economy, business and first classes, respectively. First of all, a very strong consensus emerged: out of 53 who answered this question, only 3 people disagreed with raising the fee citing low public awareness as the reason. For economy class, almost half of the experts preferred to raise the current fee by KRW 1000 (USD1) max, maintaining the total fee below KRW 2000 (USD2). However, the response was significantly different for business class and above: 56 per cent of the respondents suggested increasing the fee to the highest amount possible, namely to KRW 8000 (USD8) and to KRW 10,000 (USD10). This pattern was the shared trend in both rounds of surveys distributed 7 months apart.

Although air ticket solidarity levy has been a predictable and stable financial source under ordinary circumstances, the past two years witnessed an inescapable and unforeseen exception. In other words, it illustrated how this type of fee structure could be particularly vulnerable to certain types of external shocks such as COVID-19. Increasing fees for more expensive seats could provide a partial solution to such potential disruptions in the future, since 63% of the population had supported increasing the fee for business class and above to KRW 5000 (USD5) in 2019 [

36]. Moreover, among OECD nations, charging higher rates for business and first-class seats is the norm, as could be seen from the examples of France and the U.K. [

8].

5.3. COVID-19 Implications

In the year 2020, the outbreak of COVID-19 fundamentally altered every aspect of our lives. Needless to say, health ODA policies were confronted with the monumental task of dealing with the worldwide crisis swiftly. As for Korea, President Moon, Jae-in announced in May 2020 that the country will provide USD100 million in humanitarian aid to the WHO’s World Health Assembly [

37]. Although more than 10% of total bilateral ODA in Korea was already allocated to the health sector prior to COVID-19, it will receive a substantial boost afterwards. To be exact, the budget for health ODA from Korea will see a 34% growth from KRW 277 billion (USD232 million) in 2020 to KRW 371 billion (USD311 million) in 2021.

Even in our survey, the authors found that COVID-19 loomed large in the minds of many of the stakeholders as well. It was also telling that this topic was much more prominent in the responses from the second round of surveys conducted in October than in March, which suggests that the prolonged nature of the COVID-19 crisis was profoundly impacting and actively shaping how stakeholders approach health ODA policies. For example, the three people who objected to the current direction of health ODA (Q. 3-1) did so largely due to the coronavirus outbreak. We could see this by their suggested new direction, which included implementing specific programs to prevent infectious diseases and providing vaccines to the most vulnerable populations. Furthermore, when asked what the most serious health problem would be in developing countries in Question 6, 14 people cited concerns related to all forms of infectious diseases especially in light of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic.

Accordingly, ODA stakeholders were of the opinion that the cost of dealing with COVID-19 should be incorporated in GDEF funding as a separate category. Question 11 asked which additional diseases GDEF should focus on besides the current emphasis on three categories: (1) three major infectious diseases in developing countries (i.e., HIV/AIDS, TB, Malaria), (2) neglected tropical diseases and (3) waterborne diseases. The majority of the respondents, 20 people, answered that GDEF should also address the present and new global infectious diseases such as COVID-19, on top of what it is currently handling. Likewise, the most popular suggestion for an additional area of focus for GDEF from the experts was new infectious diseases that threaten global health security such as COVID-19. Specific issues ranged from its response from R&D, vaccine and therapeutics development and system development (Q. 14). All in all, it was evident that the experience of COVID-19 has earned great interest in global infectious disease response, especially with GDEF having already supported other global diseases such as MERS, Cholera and Ebola before the COVID-19.

5.4. Policy Recommendations

As for concrete policy implications, we would suggest the following: one, to incorporate the COVID-19 agenda into GDEF, and two, to raise public awareness effectively in a timely fashion. First, extending the reach of GDEF to cover novel forms of pandemics such as COVID-19 is imperative, which will mutually benefit recipient countries and Korea alike. While preventing and eradicating infectious diseases in developing countries is a key pillar of GDEF Strategy for 2017–2021, current strategy mainly focuses on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, with little room for new infectious diseases such as COVID-19. Global pandemics such as COVID-19 not only have a detrimental effect on people’s physical health, but also on global equity [

38,

39]. As Korea’s partner countries are seriously lacking in even the most basic medical facilities and personnel, they will belong to the most vulnerable population globally and will likely suffer from its aftermath much longer than developed nations. At the same time, according to the survey results, there was a near-universal consensus among the ODA stakeholders on the success of GDEF thus far, how GDEF should actively incorporate COVID-19 issues into its agenda, and the need to raise airfare fees for GDEF especially for business-class seats and up. All of these suggest that GDEF is well-positioned as a niche area that countries similar to Korea can push as the nation’s flagship developmental policy. Moreover, Korea is equipped with much accumulated learning from its past dealings with various infectious outbreaks prior to COVID-19, such as SARS and MERS [

40]. Even with COVID-19, despite its ups and downs, Korea is often touted as the model case in terms of successfully dealing with the disease. If Korea can extract the know-hows it possesses and converts them into applicable lessons to be imparted to other nations, Korea may make a very meaningful contribution to global sustainability, especially when considering how most of the West failed miserably in their coronavirus pandemic responses.

Second, in parallel to the above, an intentional effort has to be made to raise public awareness for health ODA policies by Korea. With the advent of COVID-19, the timing for advancing this is serendipitous as the public has become keenly alert towards both the significance of health issues and the need to confront public health threats at the international level. This opens up the possibility of stronger public support for increasing Korea’s health ODA, and concretely, for the GDEF budget. Public support for ODA is widely thought to be a crucial prerequisite for any country [

41], but it is even more so for innovative development finance such as GDEF in Korea since the funding comes directly from the consumers who purchase plane tickets. As mentioned previously, public awareness on ODA is insufficient and the majority of the Korean population simply does not know much about any of the global health initiatives that the government funds. Furthermore, more than ever, garnering favorable public support is critical now as public trust in international health organizations has diminished significantly with COVID-19 [

35]. In educating the public about this issue, it would be wise to heed scholarly advice [

25] and avoid government-led aid propaganda approaches that are image-oriented. Rather, from a long-term perspective, foreign aid campaigns that are concrete and informative will be much more sustainable in building up a strong civil society and spurring a healthy public discourse on ODA matters.

6. Conclusions

We believe the Korean case of health ODA and where it stands in regard to innovative development finance, namely GDEF, is significant in a couple of ways. First, its importance comes from the country’s direct impact on the sustainability of the Eurasian region as a new and emerging donor. As explained, Korea has had a strong regional emphasis on Asia in its foreign aid tradition [

42]. Therefore, how Korea alters its strategy in health aid policies will have a substantial and immediate impact for its neighboring countries and the regional sustainability. In addition, Korea, as a new OECD DAC member, will only be taking on a more significant role in the ODA scene in the foreseeable future as the country is still in the process of meeting the pledged level of foreign aid. Second, Korea is a middle-power country coming to terms with its newly attained status. As a result, it is dealing with the novel pressure to establish a niche diplomacy that requires clear agenda setting [

37,

43]. Howe (2017) claims that these middle powers can enjoy the greatest relevance by selectively prioritizing their policies, rather than attempting to cover a wide area [

44] (p. 246). Seen from this perspective, the struggles Korea faces will hardly be unique but presumably, common and instructive to many other Eurasian nations that are fast advancing. Therefore, the Korean case can serve as an example upon which such countries can build, and even subsequently improve, their own foreign aid policies.

In sum, a stronger emphasis on GDEF with a proactive introduction of novel forms of pandemics including COVID-19 can be a strategic area where Korea can make a difference as a nascent donor. This new orientation also has a higher likelihood of acquiring public support, which is important as customers directly finance GDEF. Once again, health ODA by Korea is illustrative as it displays a possible path of middle-power activism, given its constraints common to many other up-and-coming nations. Hence, the Korean case shows how countries in a similar standing can wield innovative development finance to their own advantage, both in terms of supplementing their limited budget and creating a valuable niche area diplomatically. As the country successfully implements the suggested policy, it will be able to render invaluable support to the population that needs it the most, and to inspire policymakers around the world with a timely and effective ODA model to enhance global sustainability.

Lastly, we recognize that our study as it stands is limited in the following ways. First, it is a single-country study, which necessarily restricts the external applicability of its findings. Second, as we chose to focus on those who are directly related to health ODA in Korea, our sample size was rather limited. Third, although inevitable, the surveys were implemented in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak and therefore the answers are reflective of how the situation was unfolding at the time. We will leave it up to the future research to rectify and improve upon the shortcomings present in this paper. Furthermore, it will be particularly interesting to see a cross-country comparison on global health ODA matters. Either convergence or divergence of national opinions—and in the case of the latter, why such differences exist—will not only be informative but will also be practically helpful to forward global health agenda-setting, which will potentially have a lasting impact on the Eurasian region and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P.; Data curation, J.S. and L.P.; Formal analysis, J.S. and L.P.; Investigation, J.S.; Methodology, J.S. and L.P.; Project administration, J.S.; Writing—original draft, J.S.; Writing—review & editing, L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant: INV-003242).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University (IRB number: ewha-202004-0013-01 and date of approval: 7 April 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects who agreed to do the surveys.

Data Availability Statement

Data not available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. Participants of the surveys did not agree for their data to be share publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Acknowledgments

The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the authors’ affiliated institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations ESCAP. Sustainable Development Financing: Perspectives from Asia and the Pacific; United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. Health and Development; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, A.; Eweje, G. The COVID-19 pandemic: Female workers’ social sustainability in global supply chains. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.; Raza, S.H.; Abbasi, S.; Aktan, M.; Farías, P. Sustainable or a butterfly effect in global tourism? Nexus of pandemic fatigue, COVID-19-branded destination safety, travel stimulus incentives, and post-pandemic revenge travel. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Active with Eurasia; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.; Jung, K.; Sul, J. Searching for the various effects of subprograms in official development assistance on human development across 15 Asian countries: Panel regression and fuzzy set approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CIDC. Third Mid-Term Strategy for International Development Cooperation 2021–2025 (Je 3cha Kukjegaebalhyupryuk Jonghapgibongyeheok(an) 2021–2025); Committee for International Development and Cooperation: Sejong, Korea, 2021. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, N. International cases of air ticket solidarity levy. J. Int. Dev. Coop. 2007, 3, 7–16. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Meghani, A.; Basu, S. A review of innovative international financing mechanisms to address noncommunicable diseases. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development; United Nations: Monterrey, Mexico, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Declaration on Innovative Sources of Financing for Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. UNITAID—Innovation for Global Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.who.int/global-coordination-mechanism/working-groups/unitaid.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Park, K.H. Adoption plan of the global poverty eradication contribution. J. Int. Dev. Coop. 2006, 11, 7–10. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T. Beyond ODA: In search of innovative sources for international development aid. 21st Cent. Pol. Sci. Rev. 2012, 22, 87–114. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, D. Innovative financing and sustainable development: Lessons from global health. Wash. Int. Law J. 2015, 24, 495–515. [Google Scholar]

- Atun, R.; Knaul, F.; Akachi, F.M.; Frenk, J. Innovative financing for health: What is truly innovative? Lancet 2012, 380, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovljevic, M.; Cerda, A.A.; Liu, Y.; Garcia, L.; Timofeyev, Y.; Krstic, K.; Fontanesi, J. Sustainability challenge of Eastern Europe—historical legacy, Belt and Road Initiative, population aging and migration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The domestic politics of international development in South Korea: Stakeholders and competing policy discourses. Pac. Rev. 2016, 29, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIDC. 2022 International Development Cooperation Implementation Plan (‘22nyeon Kukjegaebalhyupryuk Jonghapsihaenggyeheok); Committee for International Development and Cooperation: Sejong, Korea, 2021. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- KOICA Website. Available online: https://www.koica.go.kr/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- MOFA & KOICA. 2017–2021 Global Disease Eradication Fund Implementation Strategy (2017–2021 Kukjejilbyungtoichigigeum Saeopchoojinjeonryak); Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Korea International Cooperation Agency: Seoul, Korea, 2017. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- MOFA. Press Release: Korea Decides to Provide GPEF of US$21.2 Million for African Refugees. 2016. Available online: http://www.mofa.go.kr/www/brd/m_4080/view.do?seq=360737 (accessed on 14 February 2021). (In Korean).

- Koo, J.; Chung, J.; Sohn, N. An analysis on the determinants of individual’s attitude toward ODA (Gongjeokgaebalwonjue daehan gookmintaedo gyeoljeongyoin). Korean J. Soc. 2018, 52, 115–158. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KIPA. 2019 ODA Public Awareness Survey (2019nyeon ODA Gookmininshikjosa); Korea Institute of Public Administration: Seoul, Korea, 2019. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.N.; Kalinowski, T. Only shallow? Public support for development cooperation in South Korea. Asian Int. Stud. Rev. 2020, 21, 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, T. Can information change public support for aid? Asia Pac. Pol. Stud. 2019, 255, 2162–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Booker, J. Eliciting and Analyzing Expert Judgement: A Practical Guide; American Statistical Association and the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher, W. Forecasting: An Appraisal for Policymakers and Planners; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.; Kim, D. A study on suggestions for tourism ODA in Korea: Focusing on the survey of experts’ recognition (Woorinara Gwangwang ODA Choojinbanghyange Daehan Yeongu: Jeonmoonga Insikjosareul Joongshimeuiro). J. Tour. Lei. Res. 2016, 28, 25–40. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, H.; An, J.; Han, S. An explanatory strategy on the global partnership for effective development cooperation (GPEDC): Applying the Delphi method (Busanglobalpartnership(GPEDC) hwalseonghwa Jeonryak Dochooleul Yuihan Tamsaekjeok Yeongu: Delphi Bangbeopeul Jeokyonghayeo). Int. Dev. Coop. Rev. 2021, 13, 81–100. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.S.; Park, J.H. Improvement of Appraisal System and Methods for Ensuring Effectiveness of Grant-Aid ODA Project (Moosangwonjosaeop Wonjohyogwaseong Jegoreul Yeuihan Gookgabyeol Shimsa Ganghwabangahn); KIPA Report 2016-33; Korea Institute of Public Administration: Seoul, Korea, 2016. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- KIPA. 2017 ODA Expert Satisfactory Survey (2017nyeon ODA Jeonmoonga Manjokdo Josa Yeongu); Korea Institute of Public Administration: Seoul, Korea, 2017. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- KIPA. 2019 ODA Expert Satisfactory Survey (2019nyeon ODA Jeonmoonga Manjokdo Josa Yeongu); Korea Institute of Public Administration: Seoul, Korea, 2019. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Choi, H.; Lee, J.; Kang, C. The Giving Mind: Analysis of South Korean Public and Elite Attitudes on ODA; The Asan Institute for Policy Studies: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Chung, S.H. COVID-19 that shook the international order: The rise of human security and value-oriented solidarity. Iss. Anal. 2020, 5, 1–25. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, B.C. 63% of the Population, Agree to Differentiating Disease Eradication Fund Fees by Seat Class, Find KRW 5000 Appropriate for Business Class; Yonhap News: Seoul, Korea, 2019; Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190911087100001 (accessed on 14 February 2021). (In Korean)

- Donor Tracker. South Korea’s Moon Jae-in Calls for Global Solidarity, Vaccine Development, Legally Binding Health Regulations at World Health Assembly; Donor Tracker: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://donortracker.org/South-Korea-Moon-Jae-vaccine-development-legally-binding-health-regulations-World-Health-Assembly (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Gauttam, P.; Patel, N.; Singh, B.; Kaur, J.; Chattu, V.K.; Jakovljevic, M. Public health policy of India and COVID-19: Diagnosis and prognosis of the combating response. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furceri, D.; Pizzuto, P. Will COVID-19 have long-lasting effects on inequality? Evidence from past pandemics. IMF Work. Pap. 2021, 127, A001. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2021/127/article-A001-en.xml (accessed on 20 January 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Hwang, C.; Moon, M.J. Policy learning and crisis policy-making: Quadruple-loop learning and COVID-19 responses in South Korea. Policy Soc. 2021, 39, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, M. Development aid: What the public thinks. In ODS Working Paper 4; Office of Development Studies, United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.M.; Ha, E.; Kwon, M. South Korea’s global health outreach through official development assistance: Analysis of aid activities of South Korea’s leading aid agencies, 2008–2012. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2015, 2, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haua, V.; Matthias, J.S.; Hulme, D. Beyond the BRICs: Alternative strategies of influence in the global politics of development. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2012, 24, 187–204. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, B.M. Korea’s role for peacebuilding and development in Asia. Asian J. Peacebuild. 2017, 5, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).