1. Introduction

Focus on social innovation, both academic and policy-oriented, has increased substantially lately in the hope of offering (albeit partial) solutions to the unresolved challenges by dominant governing methods. Social innovation has been supported by governmental policies and institutions as well [

1] and has become a “buzzword” in social policy [

2], appearing in various high-level documents including even the collection of inspiring stories put forward by the European Commission [

3]. In this policy environment, especially in pre-COVID-19 times, the approach of partially curtailing and decentralizing public welfare responsibilities, fostering social innovation and social entrepreneurship was regarded as an appropriate solution to tackle unmet welfare needs in a fiscally and socially prudent way, through which a socially inclusive market economy could be stimulated.

The concept of social innovation is old and has been evolving over a long period of time. In short, it “refers to localized social initiatives that address unmet social needs through a transformation of social relationships that empowers people” [

4] (p. 1). It has been applied in various fields, among other things to describe the fundamental changes taking place in the field of governance, to analyze the transformation of the public sector’s role as a decision maker and a service provider, or the increasing civic participation in policy development and delivery, particularly in the field of social policy [

5,

6,

7]. It has also been used to describe the changing politicizing of cities, where new movements engaged in urban politics transformed the entire arena of local governance and local political dynamics [

2]. In this context of urban movements, social innovation can also be viewed as an opportunity to change the local spatial dynamics, not only to develop new ideas (products, services or models) but to allow urban spaces to recover and renew, providing actors and institutions with the possibility to learn and evolve [

8].

The process of social innovation can be supported and carried out by various bodies, moving on the spectrum between formal, well-established actors to non-formalized initiatives, transient in nature. NGOs, small-scale bottom-up citizen initiatives as well as more established third sector organizations or social enterprises are crucial players in the field, united by their goals with the aim to bring about social change. In fact, social enterprises represent a very particular mix between economic and social goals, where through their “transformative social ambition”, the provision of goods and services becomes the means to support social objectives and initiate social change [

9].

There is a less-talked-about “dark side” to social innovation, however [

10]. Social innovation is by definition disruptive [

11], providing its impact through viewing, understanding and approaching problems and issues through a new lens. It applies unconventional methods and even redefines the problems to be addressed. It also offers new coalitions of stakeholders to overcome the difficulties. However, the disruption of former boundaries can have adverse, unintended consequences. Disruptions in social relations can most acutely impact the vulnerable, despite the fact that a significant part of social innovation interventions aim to help exactly these groups. Additionally, the creation of a new normal, which is the higher goal of many initiatives [

12], requires rebuilding new structures—even boundaries—and new governance systems to support them to become more resilient. A challenging task, fraught with internal and external complications that puts a strain not only on the recipient of services, but also on the organizations themselves, who embody social innovation. Resilience in their case means not only finding their role, but cementing it in the new environment, while allowing them to pursue their original path. This process can still include change, albeit a gradual one, in the sense of evolutionary resilience by Davoudi which incorporates cautious transformation [

13].

The current article asks how civil society actors, as forbearers of social innovation, can create a resilient framework that not only supports their activities but sustains them as an organization. It focuses on the question of how social innovation can be maintained on the long run? How can the organizations pioneering social innovation become resilient, and what type of support do they need? The article uses the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns as a special occasion, which prompted organizations to react and at the same time amplified the key question of resilience: how can bottom-up initiatives survive? Through the lens of the first lockdown, this paper views the transformation of civic initiatives, gauging their capacity to adapt flexibly to new situations. It selects cases from all over Europe, where the first wave hit at approximately the same time, and analyses them. While doing so, it brings together the concept of social innovation and resilience, enriching resilience studies through this direction.

While there have been critical approaches to the combination of these two concepts, the current paper support the assumption of Westley that social innovation and resilience mutually enhance each other looking at “social innovation as a particular dynamic that increases the resilience of social systems and institutions, through introducing and structuring novelty in apparently “trapped” or intransigent social problem areas” [

1,

14,

15]. The paper’s emphasis on bottom-up initiatives during COVID-19 is also novel, as attention so far has tended to concentrate more on the adaptation efforts of big organizations or public authorities [

16,

17].

The structure of the paper is as follows. After a (2) brief introduction of the topic of resilience where it identifies three key strategies that bottom-up initiatives can follow, it lays out the (3) methodology how cases were selected and analyzed. Then, it describes the (4) resilience strategies followed by the selected civil society actors using the theoretical framework introduced. Finally, the paper (5) discusses the main findings and contributions and closes with (6) concluding remarks.

2. Identifying Resilience Strategies

The concept of resilience primarily comes from ecology and system theory, and its application today is still heavily influenced by its origins [

18]. It can be understood as “the capacity to adjust to threats and mitigate or avoid harm”, as offered by Pelling [

19]. He also notes that we can understand resilience in a number of ways, according to different disciplines, but the above definition corresponds to societal phenomena at times of crisis, referring to the ability of entities to withstand unforeseen challenges.

Resilience and its conceptual consequences have attracted special focus in urban studies, both on an academic and a practical (policy) level. The acceptance of resilience as a guiding theory into socio-economic governance frameworks has contributed to an approach where crisis and the need to change have become part of the daily discourse of public authorities and NGOs, and the need to adapt and prevail have become central guiding principles for cities and local communities/initiatives alike [

20].

Resilience is also understood as a coping strategy, a systemic reaction to stress—such as the COVID-19 pandemic—supporting the evolution of new norms and values [

21]. The pandemic has generally sharpened the scientific focus on resilience, bringing to the forefront how sudden events and the general rise in turbulent problems test governing capacities and require new governance strategies [

16]. It highlighted the need for integrated, comprehensive approaches in resilience strategies and has also contributed to an increased awareness about the multi-faceted nature of resilience, showing that it was dependent on a variety of factors including territorial, political and governance characteristics [

17,

22].

To analyze the resilience strategies followed by social initiatives, the paper adopts an ecologically rooted understanding of the concept, which reflects how systems work in nature, thus stressing the importance of decentralized institutions that allow local adaptations and a responsive form of local governance [

23]. It follows the footsteps of Davoudi [

24] and uses her evolutionary resilience concept as a point of departure, stressing the importance of constant change, acknowledging that there are a multitude of ways to reach equilibrium/stability. The paper takes the concept a step further and argues that the resilience of these organizations requires flexibility and adaptation, which are essential characteristics that allow them to change and to face and overcome challenges of various kinds.

The concepts of flexibility and adaptation have both been used in connection with resilience before, emphasizing that an adaptive governance system has the ability not only to self-organize, but also to co-manage and transform. Similarly, flexibility is essential to support experimentation, as well as to accommodate changes on a multi-governance scale [

25]. Flexibility is also directly linked with resilience and proactivity in risk management studies [

26]. Finally, both flexibility and adaptation have long been associated with resilience in studies in psychology and business [

27,

28,

29], but less has been said about their role regarding civic initiatives or even municipalities. Importantly, their role as possible building blocks in resilience strategies has not yet been explored.

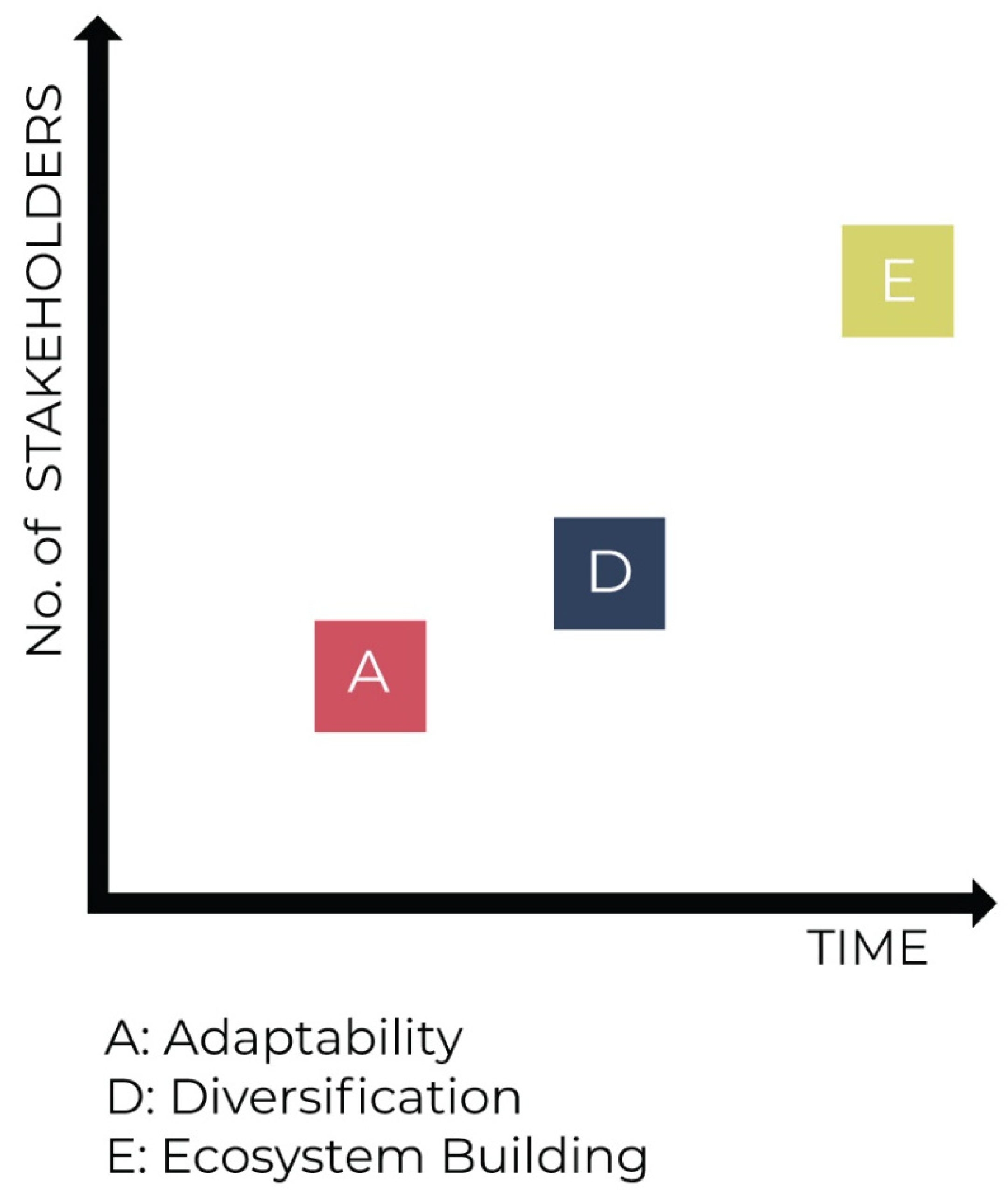

This is exactly what the paper sets out to do when it defines three main strategies depending on the various degrees of flexibility and adaptation they require. Each of these strategies allow civic organizations to overcome crises and become resilient. The strategies, although separate, can build on and strengthen each other, and can be applied by different organizations or by different branches of the same organization in a similar environment, even simultaneously. Nevertheless, there are marked differences among them both in the amount of time their execution needs and the complexity of the task it creates, as described below and also shown by

Figure 1.

The first strategy is about increasing adaptability. This is defined as the capacity of an initiative or organization to adjust to changing circumstances even without intensive exchange with others and carry it out mostly relying on its own resources. While the advantage of such a strategy lies in the fact that it can be deployed alone, from an organizational point of view its application requires a very high degree of flexibility and the biggest adaptation/transformation in a short time span. Civic initiatives resorting to this strategy need to have reserves either financially or have appropriate knowledge, network and enough personnel, possibly including volunteers as well.

The strategy of diversification refers to the ability of an initiative to establish new connections within its social, economic and territorial context and to build resilience through the provision of new services or the creation of new goods. This requires both flexibility and adaptation, but to a lesser extent than previously. However, it also needs deep local embeddedness and knowledge about missing services or any niche activities.

Finally, the strategy of ecosystem building is focused on network building that enables individual organizations to join forces and complement each other by moving resources and capacities more efficiently according to emerging needs. While this is the most time-consuming strategy, this allows individual organizations to retain their original profile in face of a crisis and, thus, requires the least flexibility and adjustment from them.

3. Methodology

To validate the theoretical structure explained above, the paper employs a qualitative case study methodology. A qualitative approach in general is applicable to a small sample size and less standardized data collection methods [

30], which is the case here. The case study methodology provides the opportunity for an in-depth understanding of how different initiatives managed to build up resilience strategies facing the COVID-19 crisis. This method is particularly useful to discern factors determining the success of these resilience strategies, but it also allows comparisons. The latter helps to see how the respective local environment influences the strategies chosen by the initiatives.

There were three main sources the cases for this paper were selected from:

The Urban Development Network Program’s (URBACT) Civic eState project (

https://urbact.eu/urban-commons-civic-estate, accessed on 16 January 2022) which involved six city municipalities (Ghent, Amsterdam, Naples, Iasi, Presov and Gdansk) dispersed around the EU. The project focused on new models of urban co-governance based on the commons idea, with the goal of creating policies that support sustainable urban commons, enabling inhabitants and local communities to self-organize and collectively act for their common good.

The webinar series “Cooperative City in Quarantine”, which collected stories of civic activation during the first wave of the pandemic in the spring and early summer of 2020. The series was looking to see how COVID-19 and the ensuing quarantine measures were transforming cities around Europe. Each webinar focused on a specific topic, and in total 13 episodes were hosted, with the involvement of 69 experts from 36 different cities. The stories of these projects are also covered in the publication: “The power of Civic Ecosystem” (

https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/the_power_of_civic_ecosystems_full_book_vsm.pdf, accessed on 16 January 2022).

The OpenHeritage project (

www.openheritage.eu, accessed on 16 January 2022), which is an EU-funded research and innovation project, focusing on the adaptive reuse of buildings and sites by the local communities in marginalized areas. As such, it has worked closely with 6 labs and 16 observatory cases all over Europe for the past 4 years, each of them involving bottom-up initiatives embedded in their respective local communities.

From this rich source material, cases were selected for a closer inspection based on their relevance to the topic of the current paper. Primarily, we were looking for cases where the pandemic created a situation of a sudden challenge needing immediate intervention to sustain the organization itself, its community or both. We only looked at cases that involved social-innovation-focused initiatives as we wanted to see the specific patterns their actions showed. Secondly, the selection also took the various institutional backgrounds into consideration, supposing that the existence of a supportive environment strongly influences the resilience strategies chosen by the initiatives. Thirdly, we wanted to provide a relative difference in size of the initiatives, assuming that more established ones could react differently, having more financial and network resources at hand. Finally, we made the conscious decision of involving cities as cases, since their elaborate programs could influence the resilience strategies followed by the initiatives locally. Municipalities often realize their programs through activating local civic initiatives and their support is necessary for these initiatives to build their resilience strategies.

Using the above criteria, 8 cases were finally selected (see

Table 1 for their list) for a more in depth inspection. They span geographically between Portugal and Hungary, allowing the collection of vastly different experiences and versatile strategies, all of which were effective in the same constrained timeframe of the first COVID-19 lockdown. They are either bottom-up initiatives themselves or are organizations/institutions working closely with bottom-up initiatives. Among the chosen initiatives, there are some which can rely on strong municipal support, whereas others were left more to their own devices during a crisis. All the initiatives selected use space—both urban and rural—as an opportunity to transform their surroundings and they all have basic social innovation aims, which is more apparent in some cases, while in others, it has been constantly in the background of many of their projects.

The data about the cases come from interviews with members/participants of the initiatives, but not from the local communities. As a result, these reflect their internal views. Given the paper’s focus on organizational strategies, this was not regarded as a problem. Interviews were always conducted with someone who had sufficient overview and knowledge to assess the internal operation of the initiative involved. The questions asked were divided between pre-COVID-19 activities and then emergency interventions.

Additional information comes from presentations and desktop research using background materials of the OpenHeritage, the URBACT projects, as well as the recordings and transcriptions of the Cooperative City webinar series. The following table (

Table 1) summarizes the exact sources of information for every selected case.

In the following, the paper will examine these cases in light of the strategies followed to support resilience. For each resilience strategy, the paper gives various examples, explaining how it was executed by the organizations, also highlighting the role of flexibility and adaptation played in the development of these strategies.

4. Applying Resilience Strategies

4.1. Adaptability

For Keck and Sakdapolrak [

53], adaptability (adaptive capacity) constitutes a dimension of social resilience: the ability to learn from past experiences and adjust to future challenges in everyday life. Considered as such, adaptability represents a dynamic quality empowering social system—including civic initiatives supporting social innovation—to respond and cope with crises as a normal rather than exceptional condition. In an urban environment, together with the transformative dimension of social resilience, adaptability proposes new scenarios for social and spatial development. In this sense, adaptability can be seen as a dimension of the type of open urbanism envisioned by Richard Sennett [

54] and meant to represent a flexible environment, not over-determined or fully defined a priori. This kind of openness nurtures social innovation and leads to new ways of considering the city and the challenges society is called to face, allowing for quick and speedy reactions.

Adaptability is also a strategy that requires the least time to develop, but it can support social innovation organizations to prevail in difficult times, allowing them to change—even temporarily—the focus of their activities. Importantly, this strategy allows them to act alone. Such a strategy is exemplified by Les Grands Voisins (LGV) in Paris, a project which had formerly concentrated on the temporary reuse of a disused hospital complex. Between 2015 and 2020, they have created a social and cultural space in the heart of Paris where altogether 2000 people lived and/or worked, with additional emergency accommodation for up to 1000 people. They also created spaces for workshops and offices and involved more than 5000 volunteers a year.

Following the outbreak of COVID-19, the Municipality of Paris reached out and asked Les Grand Voisins if they could help with food distribution to the most vulnerable. The connection between LGV and the city had existed prior as well, since it was the city municipality that temporarily handed over the management of an unused area to three NGOs, allowing the LGV to be established in the heart of Paris. During the first wave of COVID-19, LGV not only became engaged in providing support, but could also do this task very efficiently despite its prior inexperience and the short notice. It could adapt very quickly because its mission of work for the common good was at the base of the organization, and such an adaptation came naturally. Additionally, architects and social workers play a very important role in LGV, and they had a specific know-how on how to adapt to this new scenario. Finally, flexibility and quick adjustment to changing circumstances was already at the core of the initiative, which utilized the methodology of temporary use to test new functions and activities in an existing site with little physical transformation. Therefore, in the context of COVID-19, adapting the space for a new purpose was relatively easy, and it became not just about giving food to people, but it also meant allowing the organization to develop.

As it was summarized by Martin Locret, a project manager:

“We have been contacted by the Municipality of Paris—they asked us if we could help with food distribution, as we run our activities in empty and/or abandoned buildings. We were able to immediately say yes because we always kept in mind the fact that urban commons should be able to respond and adapt as quickly as possible”.

The COVID-19 pandemic similarly required a high level of adaptability in other places as well, often meaning the sudden conversion of their spaces for entirely different purposes. In Naples, a new “informal welfare” system was created by social centers, community groups and bottom-up initiatives, which underwent a sudden change following the outbreak of the epidemic and the subsequent quarantine measures. With all the usual activities suspended because of the lockdown, social centers, self-organized spaces and urban commons such as Scugnizzo Liberato, ex Opg, Mensa Occupata, Sgarrupato Occupato and Zero81 reconverted their spaces into kitchens or food stores, and they packed parcels to be distributed once or twice a week, using small pickup trucks, motorbikes or simply on foot. Additionally, as there was the need to raise money, the organizations designed and carried out crowdfunding campaigns. Such was the case with ex Opg, which through a word of mouth and online communication raised more than EUR 42,000 to buy supplies, personal protective equipment and other primary goods to be given to poor families, migrants and the homeless.

Adaptability as a strategy could be followed by city municipalities as well, allowing them to intervene efficiently and quickly, and supporting both social innovation and civic initiatives. During COVID-19, many municipalities converted buildings for new uses to respond to the most urgent needs, while others reached out to local initiatives and developed emergency services together, using community spaces and mobilizing the skills and knowledge organized around these spaces. Such changes required flexibility both on the side of the initiatives and on the side of municipalities.

One particular city example is the case of Milano, where the importance of adaptability is reflected by official strategies, including the Milan 2020 Adaptation Strategy [

34], which builds on public–private partnerships and recovery measures to address the current health crisis as well as future urban challenges. The strategy is aimed at supporting social innovation and social cohesion as a means to fight the effects of the COVID-19 crisis. One of the city’s immediate actions during the crisis was to have a dual use of infrastructures with a temporary conversion of buildings to make a significant contribution to the emergency management: its “Open Schools” program turned school buildings, particularly during the summer months, into community areas and green spaces dedicated to educational activities; “Milano Abitare” transformed used vacant apartments as emergency housing; accommodation facilities and other public and private facilities were also used for emergency management. In Milan, the adaptability strategy was both a way to cope with the crisis and to prepare the city for future challenges. Additionally, it also helped the city to become more resilient by adapting the available spaces to new functions.

4.2. Diversification

The capacity of an initiative, organization or partnership to successfully react to the challenges that impact its operation and to build resilience partly depends on its ability to diversify its connections to its broader social, economic and territorial contexts. Such a diversification strategy is conceivable in various dimensions and at various levels of scale and governance. However, unlike in the case of adaptability, this cannot be carried out impromptu, rather it needs planning and preparation. The most common strategy of diversification is the development of various income streams, allowing civic initiatives to have a stable economic background.

This was performed by the Gólya cooperative in Budapest, which is a bar and community house in the 8th district of Budapest, Hungary. The cooperative was founded in 2011 and the bar was opened in 2013. In 2019, Gólya moved to a new location, an industrial building bought and renovated through loans and voluntary work by the organization’s broader community. Today, Gólya combines the functions of a bar and office space, and has a daycare establishment and even a music rehearsal studio. It regularly hosts live music gigs, cultural programs, lectures, discussions, and other activities. It also hosts both public and closed events of groups or organizations. The cooperative is a one-of-a-kind social initiative in Budapest with a clear and complex social mission. Members want to work towards a just and sustainable society. As part of this, its mission includes maintaining and developing further the cooperative model of organization and production and cooperating closely with similar projects. Additionally, Gólya also provides space for groups, projects and organizations with similar goals, hoping to support the cooperative scene. Finally, it wishes to actively engage against the process of gentrification in its neighborhood.

Gólya’s original business model greatly relied on its music venue and bar. However, the arrival of the pandemic and the first lockdown drastically reduced the venue’s events and revenues, and with debts to pay back to their creditors, Gólya members began to think about how to diversify their activities and make their enterprise more COVID-19-proof. Being closed also meant that they had time to think and reorganize. Gólya members aimed to expand their activities, rethink their revenue streams and create new building blocks in the cooperative’s economic structure. As it was summarized by András Szépe, one of its founding members:

“We spent months with the venue closed and our revenue from the bar was greatly reduced in 2020. Therefore we needed to diversify our revenue streams. During the renovation process, we realized that we gained many construction and renovation skills. To put these new skills in the service of the cooperative, we launched a construction business and now we have some revenues from doing renovations in the neighborhood as the cooperative. We also established a bike delivery service as many of our members had experience working as couriers.”

Based on this process of integrating new knowledge in the organization’s repertoire, Gólya was capable of moving its workers to the delivery and renovation services when COVID-19 hit the city and the community bar had to close. This shift allowed the organization to retain all its employees while many other businesses had to fire a part of their personnel. Having the flexibility to move their employees between different activities made the organization more resilient to both long-term changes and unexpected events. Payments among the partners were also relatively evenly distributed, which is in connection with the fact that Gólya is a cooperative. This, however, also means that the model might have limited applicability under different circumstances. In Gólya:

“Everybody works according to their skills, some with building, renovating, some with couriering. Each member gets paid according to their needs. This is how we are surviving the current pandemic period.”

A similar diversification strategy could be seen in Cascina Roccafranca (CR) in Turin, which is similar to Gólya in many respects, albeit on a larger scale. The initiative is a multi-functional community center operating in a building owned by the City of Turin in the outskirts. It includes a renovated old farm building and a giant courtyard. CR provides a diversity of services to locals and people from other parts of the city alike, including an area dedicated to informing and listening to citizens, a free help desk, a day care center, a restaurant and a cafeteria, all run by the same social cooperative. The place hosts a variety of cultural activities and different courses. Although CR was established with the help of European funding in 2007, the project strives for independence in an economic sense: by 2020 it could cover 66% of all of its expenses, a giant improvement from the original 33%. This was only manageable with the help of continuous diversification of their economic portfolio. Their income comes from the establishment of commercial activities in support of the project: the restaurant and the cafeteria are run by a social enterprise, the rental of space for activities, courses or private parties bring in important revenue for the organization, but they also do fundraising

However, next to its economic diversification, CR also pushed through the diversification of its decision-making process. As a result, its governance structure includes a variety of organizations besides the municipality, and a public–private foundation was created to manage it. It has a “Board of Directors” with five members: three of which are nominated by the City of Turin (the Councilor for integration policies, the President of the 2nd District and one member appointed by the District) and two members are appointed by the “College of participants” (made by 45 associations and groups that operate in the Cascina). This structure ensures that a multiplicity of voices and ideas are heard in the decision-making process that concerns the future of the building complex. Such a diversity of voices helps the organization to remain open for a variety of opportunities and stay sensitive to changes that affect it.

This diversification was very important during the pandemic, when Cascina reconfigured itself into something different. The City of Turin asked them to become a strategic node for food distribution. (Here, there is a similarity to LGV mentioned above, showing that food distribution became of primary importance for many social initiatives during the first wave of the pandemic.) This sudden transformation required great flexibility, as it was acknowledged by Stefania Masi, the project manager of CR:

“A couple of things we already knew were consolidated, like the importance of flexibility. We have never stopped, when COVID arrived we tried to understand as fast as possible how we could adapt to the new situation and still be useful and relevant for our community. We didn’t want to be strictly cultural and so we thought of adaptation with an open mind, using our networks, skills and resources to help our community.”

As a result of the successful transformation, CR could not only reach out better, but could also better understand the needs and problems of the locals. It also became very active during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, providing counselling desks, working on psychological help, assisting women victims of violence and helping people that lost their job during the lockdown. Importantly, besides helping those in need, this strategy also helped Cascina to stay relevant for its own community and thereby supported its resilience on an organizational level. This latter point has been very important to Ms. Masi, who emphasized that:

“Finally, we understand the value of our work: during COVID, when we were not able to continue our activities, people missed us a lot. When we could reopen again it was beautiful to see the importance of our work. Frequently, social and cultural life is seen as a secondary thing, not so necessary to life, but this pandemic could show to everyone our importance.”

4.3. Ecosystem Building

The most complex and also most time-consuming resilience strategy is ecosystem building. Ecosystems connect civil societies and support social innovation while supporting unconventional collaborations between initiatives and organizations that are normally not in touch with each other. A civic ecosystem is multifaceted, including actors from different branches and groups of varying levels of institutionalization, between informality and volunteer associations to professional NGOs. They often have the tacit or even outright support of their local municipalities. As an ecosystem is based on connections and collaborations, the more the constituting organizations are connected and work in a complementary way, the better they can respond to new challenges, by distributing or pooling their resources when needed [

55]. Additionally, such networks can help the building of synergies and the diversification of connections, thus relying on a variety of resources, audiences or revenue streams. Grouping or clustering initiatives in networks or umbrella organizations can also help to lower the operational thresholds of initiatives, reducing costs and other efforts, and enabling them to concentrate on their work. Such an ecosystem can also react very fast and with relatively little risk to challenges. Previous emergency situations have shown the importance of local networks and civic ecosystems. These could successfully complement municipalities in providing support and services to the local population. In turn, belonging to such networks could make individual initiatives and independent civic spaces stronger and better established.

In Dubrovnik, the lockdown during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic created an entirely new situation: with the immediate suspension of flights and ferries, the city suddenly found itself without tourists, a rare sight in this otherwise heavily touristified city, meaning severe economic consequences both for the city’s industries and its civic sector. For Dubrovnik’s civic ecosystems, the shift from physical to virtual has been fast, and their responses to the COVID-19 situation outperformed the slower and less-adaptive reactions of state structures, city departments and public institutions.

To respond to COVID-19, the cultural center of Lazareti in Dubrovnik mobilized its networks of makers to help the local community in various ways. The center itself is a historic complex renovated for social and cultural uses including hosting workspaces. While the complex was empty, the NGOs working there used their resources to provide relief for the community. Each organization started to do something different: they became engaged in producing 3D-printed protective shields and masks, but at the same time, youth workers and psychologists launched online services and educational courses. The already-existing connections with producers and service providers helped the center to protect its community and strengthen its role in Dubrovnik as a key player in the city’s social infrastructure. Additionally, the Platform for Lazareti, which is the network organized around the community center, also began collecting daily memories and habits of people in its community. They organized an online exhibition displaying these, hoping to connect people during the insecure quarantine times and thus contribute to their psychological well-being by making people feel that they are part of a supportive community.

Such actions helped to strengthen already-existing connections in the city and build new ones around Lazareti. A stronger local ecosystem of cultural, creative and social actors made the city more resilient to unforeseen future events. As Petra Marcinko, the coordinator of the local art workshop explains about these times:

“Younger activists and volunteers are getting closer to older generations, listening more to their needs and doing their best to look after them. I actually think this played a crucial role in keeping the number of infections so low in the city.”

COVID-19 has also taught the group running the center to expand their thinking and involve public authorities in the process of ecosystem building, underlining the special role reliable funding streams play in the development of local ecosystems.

“We realized that we need to better communicate with the government, informing them about local needs and issues. We need to educate the government about the importance of our work, tackling cuts to funding. A lot of people remember the war, so they know the importance of services like ours, as in times of emergency the state didn’t have the means and the time to follow local communities and especially disadvantaged groups.”

This more active public role in ecosystem building is also tangible in Naples, where the city has been experimenting with specific policies of a shared and participatory urban management system since 2011. They aim to identify and implement local policies inspired by the concepts of the commons. Commoning has become a central topic in local public policy, with a dedicated department, allowing the gradual development of a local ecosystem ripe with various organizations, many of them social innovation focused, that are closely connected. This proved very helpful during the first COVID-19 crisis, as even before the city could act, thanks to a wide network of associations, cooperatives, soup kitchens, social centers and urban commons, many inhabitants received concrete support early on. Using the ecosystem in place, activists, volunteers and social workers created solidarity networks to support the weakest groups of inhabitants from the first hours of lockdown with the distribution of food and small economic contributions. With the help of a dense interweaving of telephone calls, Facebook groups, Telegram chats, and wiki-based platforms such as viralsolidarity.org, it was possible to track down those in need and enabled active citizens to intervene house by house. Given this situation of isolation, several urban commons provided psychological support with dedicated telephone numbers (such as Villa Medusa) or legal assistance via chat or email (such as l’Asilo). Santa Fede Liberata opened its doors to give shelter to the homeless. Giardino Liberato di Materdei, together with activists from other communities, contributed to the creation of Radio Quarantella, a web radio with an open editorial board that collected voices from quarantine – not simply from the districts of Naples but from all over the world.

The extraordinary situation faced by cities such as Naples during the pandemic highlights the essential role of self-managed or co-managed spaces of aggregation and mutualism. This was performed in Naples in adaptive reuse buildings where the political activism of some groups has led the administration to carry out a process of innovation in the government of the city with the recognition of civic uses for the activities carried out in seven properties led by the experience of L’Asilo (Villa Medusa, Ex Lido di Pola, Ex OPG, Santa Fede Liberata, Scugnizzo Liberato, Ex Schipa). In fact, the informal and community-based welfare system that active citizenships have been building in Naples for years has confirmed its capacity to react quickly and in a targeted way to the local needs, especially when emergency circumstances required a decentralized approach. This also confirms the important role of urban commons as viable ecosystems, social infrastructures capable of adapting themselves to different challenges, producing public services of social impact through solidarity, creative, collaborative, digital and circular economy initiatives. Finally, it also shows that due to their complexity, ecosystems do not lend themselves easily to central control and planning, but the role of a more central author in creating an enabling legislation or a support system is essential [

25].

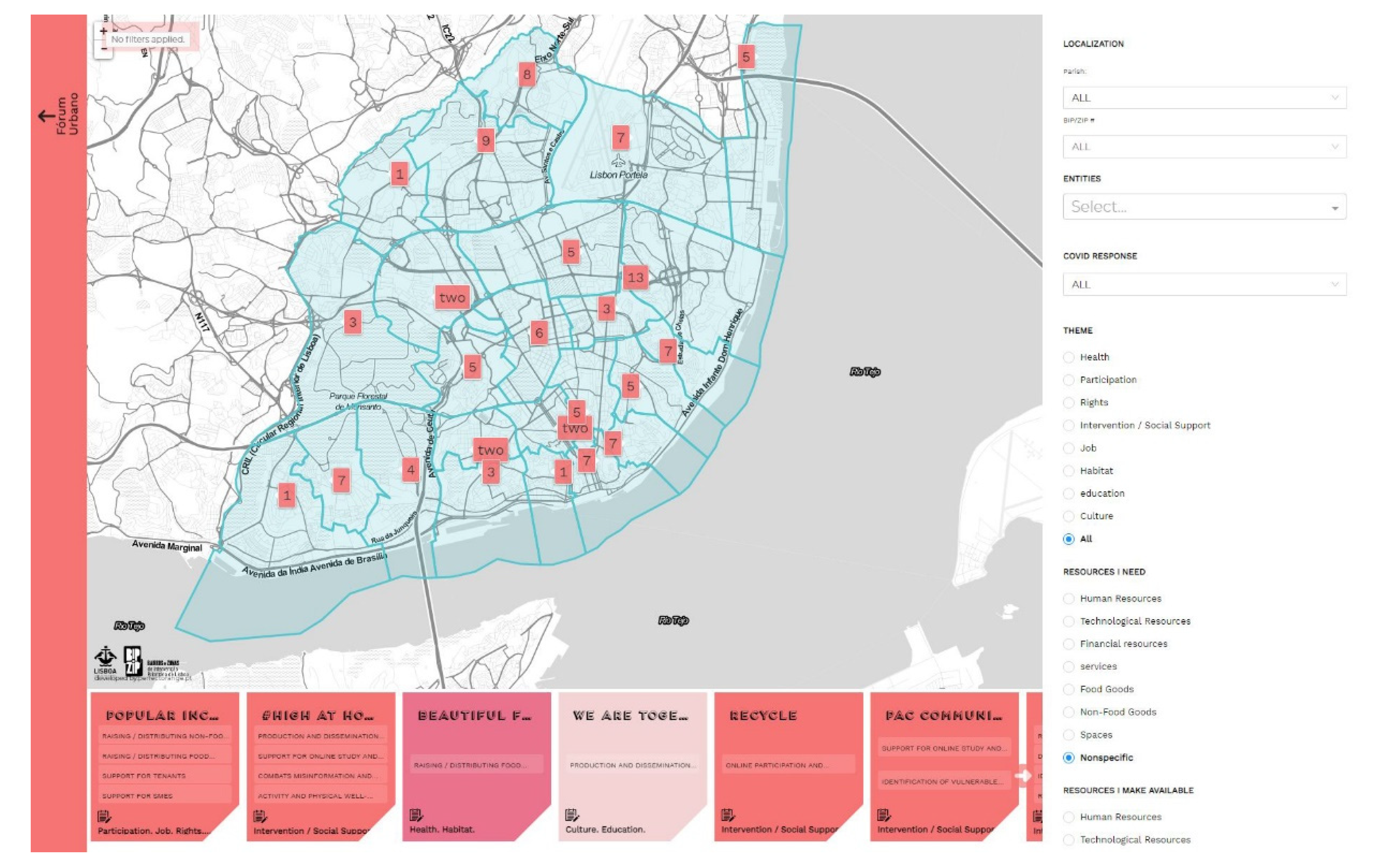

This last point is best exemplified by the city of Lisbon, which has shown a strong commitment to ecosystem building from an institutional side through its decade-old BIP/ZIP program. This program promotes local development and partnerships in the city’s priority neighborhoods. In addition to establishing local governance structures that facilitate communication and shared decision-making between the public administration and neighborhood organizations, BIP/ZIP also includes an ignition funding program for community partnership initiatives with a strong local impact. Competitions for seed funding are opened in the priority neighborhoods and coalitions of local initiatives and organizations can apply. The actions are implemented by the civil society itself in the BIPs/ZIPs, with the financial and technical support of the City Council. The structure of these competitions encourages partnerships and networking in neighborhoods where new alliances are most needed. As pointed out by Rui Franco, one of the main architects of the program:

Politically, in Lisbon we started our BIP/ZIP strategy a decade ago. This strategy proved that it is way more efficient to resource bottom-up initiatives than directly acting from higher levels. Empowering bottom-up initiatives can create a more resilient city. What is happening now is that our ecosystem is much more organized and efficient. Moreover, communities are making their voices heard, influencing political decisions and contributing to a better distribution of funds for inclusive projects.

During the first COVID-19 lockdown, Lisbon’s Housing and Local Development Department together with the Fórum Urbano project used this BIP/ZIP program to provide immediate help for the residents but also to support local initiatives by giving them clients outside of their own neighborhood. As a result, an interactive online map was created, listing all the social initiatives that had been part of its long running BIP/ZIP program, as shown by

Figure 2 below.

The initiatives were very different, and they provided a variety of services from psychological help to hospital equipment, and from food support to cultural services. At the same time the message sent by the Lisbon Municipality was clear: in such a moment of emergency crisis, projects from the BIP/ZIP program fostering local development in different priority areas, were called to demonstrate their social value.

“What we have been facing for the last three months here is that everyone with less stability and no savings tends to suffer way more than average citizens. For instance, a teenager from a wealthy family will not experience issues with e-learning access, while poorer kids will find themselves struggling to even get to participate in classes due to poor internet connection and/or die to the fact that poorer families with more kids may not have the chance to provide devices for all family members. This perpetuates the mechanisms of exclusion of the poorer layers of society. As we have always done, we are targeting the causes of inequality and we are working with the Municipality of Lisbon and with other stakeholders to give everyone the chance to build a decent and happy life.”

5. Discussion

A resilient organization is capable to “absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedback” [

56]. It is also capable of learning and self-organizing, allowing the maintenance of its core functions, while responding to a crisis [

57]. Organizations that are flexible and able to adapt can find it easier to face financial and political challenges and crises of various kinds and degrees, including the COVID-19 crisis. The cases introduced in the paper have all successfully survived the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. They have shown that social innovation-focused civic initiatives of different aims and sizes actively engaged with their local communities during the lockdowns and created strategies that have contributed both to their own resilience and to that of the community around them. Their actions taken mutually reinforced these two aims but also connected them better to their communities.

The question remains of if there is an ideal resilience strategy to follow for them among the three identified. The diverse cases introduced by the paper show that there is no best one, only an appropriate one. Nevertheless, there are certain elements that are decisive regarding what resilience strategy seems to be fitting. These are time, the role of municipalities and the availability of resources.

Overall, there is a contradictory relationship between the time needed for a strategy and the sudden change its application requires. The more time there is to build and follow a sound strategy, the less flexibility and adaptation is required on an organizational level. While adaptability necessitates the capacity to change fast, ecosystem building allows stakeholders to undergo slow change while keeping their original profiles and aims practically unchanged. Adaptability is a strategy that focuses on one organization and can (often) be implemented in a relatively short time. Individual organizations can react fast, as the case from Paris has shown. Both diversification and ecosystem building are longer processes. They, however, create the foundations necessary to adequately respond both to slow-burning transformations and emerging challenges. In case of Naples or Lisbon, decade-long activities created a local scenery, where the individual groups could not only rely on themselves, but also exploit the resources of an entire ecosystem network. Importantly, organizations in the local ecosystems did not need to change their profile: as a result of the well-built ecosystem, only flexibility was required from them to adapt to a new clientele and not to change their profile.

While ecosystem building always needs more stakeholders, the strategy of diversification is possible to carry out as a single organization. Gólya in Budapest operates in an environment lacking the supportive policies of Milan, Naples or Lisbon, but it still managed to develop new business branches. Gólya was pushed into diversification by the long months, when its bar had very few guests. This also illustrates that the biggest bottleneck of success for diversification is time, as the development of new functions and services does not happen overnight. Importantly, diversification requires little public support, and if carried out well, it could be the basis of sustainable business development models in the future. For small initiatives, it is a conceivable strategy to follow even in places where the NGO scene is volatile or underdeveloped. All in all, despite the high level of flexibility shown, extreme challenges—such as a pandemic—can overstretch the capacities and possibilities of initiatives. The lesson from Turin’s Cascina Roccafranca shows that even with well-diversified income sources, fundraising and public support are crucial once the initiative concerned is a large complex. Gólya in turn is a small organization needing less revenues, which was helpful when, due to the pandemic, important income sources simply fell out.

In the end, it is ecosystem building that provides the biggest and most complex safety net for various organizations both in the face of short-term and long-term challenges, allowing individual organizations to share their resources, support each other and develop complementary services. Well-functioning civic ecosystems are, by nature, more cooperative than competitive and instead of growth, they aim to build systemic resilience, encourage mutual support and enable both individual organizations and the ecosystem as a whole to respond to future challenges. Ecosystems thus support shifting from a competitive relationship to collaborative interdependence with each other. As shown by the case in Naples, small, bottom-up initiatives without solid legal and financial backing could survive and provide their services once part of a larger framework, such as a local ecosystem. However, this requires a well-established and active NGO scene as an ideal environment, unimaginable without a strong institutional commitment. It also requires many years of work and public support, as shown by the cases of Lisbon or Naples. It is possible to imagine a municipality being substituted by a foundation or some other independent and non-partial stakeholder. However, regardless of the main actor, this strategy requires both a long time and a very close cooperation between various actors throughout its implementation. These two requirements can become potential bottlenecks, as direct interests are often conflicting even if the overarching goals are similar. Additionally, the building of successful ecosystems cannot happen during a crisis. Rather, as shown by the examples above, the truly successful ones are the results of long-standing cooperation, where the crisis is rather a crash test of the already functioning ecosystem.

Generally, the role of municipalities is very important everywhere: they are seminal actors who have the capacity to create a nurturing local environment that supports social innovation. The diversification of activities and decision-making processes can also be supported by municipalities. Be it capacity building or a series of trainings, initiatives can grow more conscious of opportunities to better fund or manage their projects. A close monitoring of an initiative’s operating context (from a viewpoint of a public administration) can also result in better sensitivity to invisible, structural changes in this context, such as demographic transformation resulting in different needs for community services. Municipal funds are good tools to encourage cooperation and ecosystem building, prioritizing collaboration in the local scene. Such “collaborative commissioning” or “participatory grant making” can help initiatives develop complementarity in their activities and better connect to each other. Such funds can also be completed by grants, tax breaks or loans, aiming at maintaining a civic tissue in a given neighborhood, city or region. Additionally, municipalities as well as non-profit private actors can help initiatives connect with each other, develop networks and build civic ecosystems that enable individual initiatives to grow more resilient.

The comparison of the cases also showed the extraordinary role of temporary use among the civic initiatives and their resilience strategies. Reusing these spaces and reaching out to the local communities through them plays an important role in the lives of social initiatives. It nurtures them, gives them space to develop further, to organize themselves, to adapt to their new environment and remain flexible to the extent that it contributes to their resilience. It also gives them time, as these buildings are typically not needed by other actors, at least not on a short term. In the development of the ecosystem around the Lazareti, the gradual refurbishment of the historic space and the presence of civic initiatives from early on was a crucial factor, while in Paris, a new world was created by LGV, completely reinterpreting relations between space and people.

Importantly, all cases show that resources—be them financial, knowledge or networks—are inevitable assets for the survival of these initiatives. They deployed them very skillfully during the spring of 2020, helping them to become more resilient. Non-financial ones are enough if a large actor is present—such as the municipalities of Lisbon, Naples and Paris—that provide a general supportive umbrella above the initiatives. However, for groups moving in a less-friendly environment, such as Gólya, financial stability is crucial. Additionally, even partially municipal projects such as Cascina Roccafranca need to financially plan ahead for sudden events.

The inspection through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic has also shown that resilience is a hard-won characteristic, and resilience strategies do not appear overnight. While all initiatives studied needed to act fast, they all had prior experience and knowledge to build on. For the LGV in Paris, despite the short call from the municipality, their organizational structure, their knowledge and their networks made them capable to adapt and react flexibly, to change their focus and activities from one subject to another in a matter of days. Lazareti could count on the community of artisans and workshops with which it had a long-standing connection. Actually, all the initiatives that employed a strategy of diversification or ecosystem building changed their activities to some extent but stayed within their own networks reaching out to their community albeit with different methods.

All strategies have shown that successful resilience is not a fixed state, rather that of constant change, as suggested by Davoudi [

13]. Additionally, civic initiatives, especially those focusing on social innovation, require some degree of flexibility and adaptability all the time. However, local embeddedness and a community to serve and receive support from are crucial for the development of a successful resilience strategy of a small initiative.

6. Conclusions

The paper identified three distinct strategies, adaptability, diversification and ecosystem building, which organizations and civic initiatives can pursue to support their resilience. The recognized strategies need various degrees of flexibility and adaptation from the side of the initiatives, with the first one being applicable rather immediately and the last one requiring the most time. Through the selection of cases, the paper wanted to illustrate how the above-mentioned strategies play out in practice. The selected cases were all initiatives in the pursuit of social innovation; thus, the paper also fits into the line of inquiries that seek to understand better how these initiatives connect to each other and the public sector [

5].

Focusing on the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic gave the opportunity to see how various organizations, dispersed around Europe, reacted to the same challenge—namely the pandemic and the lockdowns—in a given timeframe. While describing the ways they operated and cooperated with each other, the paper sought to highlight practices and corresponding policies that enable separate initiatives and organizations, as well as partnerships to respond better to long-term transformations and unpredictable, short-term challenges. These strategies, while requiring flexibility and adaptation to various degrees, also enable the initiatives to achieve their goals even if with slight modifications. The choice of strategy depends a lot on the environment in which an organization is operating.

By placing the resilience of organizations at the center of our analysis, the paper was able to provide valuable insights into the role of their flexibility and ability to adapt to changing environments. However, there are many ways the current inquiry could be developed further. One line to pursue would be to change the case selection method and compare the current initiatives with a selection of those who could not survive the lockdowns of the pandemic or had to—at least temporarily—stop their activities. It could be interesting to see what the fundamental differences between them and the cases described here were. If they reacted differently, what was the reason behind this, and why could the resilience strategies outlined in the current paper not work in their case?

Additionally, the role of municipalities as a supporting agency could be inspected further. One particular thread of interest would be about seeing to what extent their role can be substituted by other actors in an environment where public authorities are not so supportive. The example from Gólya is very valuable in this respect, as the initiatives that strive to build up a network from other similarly thinking cooperatives. This can also be interpreted as an attempt to build an ecosystem.

Finally, the relationship between the resilience strategies and adaptive reuse could be questioned further. The fact that many of these cases are embedded into adaptive reuse processes—e.g., the Lazareti in Dubrovnik, Cascina Roccafranca in Torino, Les Grand Voisin in Paris—provides an interesting framework for further analysis. Conceived in itself as a process of change, adaptive heritage reuse requires simultaneously physical (focusing on the building and the site) and organizational (who runs it and what is the purpose) adaptation and flexibility. Many adaptive reuse projects are central components of urban redevelopment strategies, and they have become key in repurposing urban centers, co-producing public spaces, and helping the sustainability and contributing to the resilience of lived heritage, while providing opportunities of engagement for communities and bottom-up initiatives [

24]. They have also become important testing grounds for change, allowing organizations of different sizes, backgrounds and purposes to develop flexibly and to adapt. Finally, both tangible and intangible heritage have the capacity to adapt to changes as they transform and develop through time. Meanings and understandings metamorphose, which helps to maintain the significance of cultural heritage, a process that contributes directly to its resilience [

58,

59].