A Multi-Perspective Assessment of the Introduction of E-Scooter Sharing in Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Refers to small, lightweight vehicles of max. 55 kg;

- Offers short-term rental via apps;

- Uses battery-driven vehicles;

- Offers the ride for one person;

- Is based on a dockless rental systems that allows the scooters to be left at any point in the operation area;

- Reaches up to 25 km/h with motor support.

- How do German cities differ in the introduction of e-scooter sharing and what are possible explanations?

- Which conclusions and policy recommendations can be drawn from the analysis?

2. State of the Art

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Interview Guidelines

- Status quo of e-scooter sharing operation. Exemplary questions: Since when are e-scooter sharing fleets are operating in the city? How many vehicles are available?

- Introduction of e-scooter sharing systems and cooperation with other stakeholders. Exemplary questions: Which role did the municipality play in the introduction of e-scooter sharing systems? Did the city set up a quality agreement?

- Target groups and users. Exemplary question: Are there any insights to the target groups of e-scooter sharing in the city?

- Future perspectives: Exemplary questions: Are there any plans to expand the offer or reduce the number of e-scooter vehicles? What would an e-scooter sharing system ideally look like in a year?

3.3. Stakeholder Analysis and Sampling

3.4. Factsheet of Selected Cities

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Introduction Styles of Electric Scooters

4.1.1. Market Entry

“We had a total of, I think, 14 or 15 companies, one of which was for electric motorcycles. All the others were the e-scooters, all of which wanted to come to X [city was pseudonymized]. From Start-Ups, which you have not heard about before, to American and Canadian consortia, which wanted to present themselves with a giant investment capital on the market.” (Transport authority 1).

- (1)

- No market entry after rejection;

- (2)

- Market entry with conditions;

- (3)

- Free market entry without conditions.

4.1.2. Responses to Operators

“I have not yet found a city that is not annoyed by the e-scooters.” (Public transport company).

“There is no concept and no strategy how to integrate new mobility offers. [...] there are cities that think “we don’t really need anything except public transport and bicycles.” And even though it [the city’s strategy] hasn’t caused a shift away from cars in the last 30 years, somehow that’s not taken into account.” (Public transport company).

- (1)

- Hesitation

- (2)

- Openness

- (3)

- Ignorance

4.1.3. Regulation Strategies

“It seems as if we have introduced it [e-scooter sharing systems], of course not. These are systems that operate privately and economically. In other words, they approach the cities and do this, for example they introduce the offer on the basis of the existing legal framework […].” (Transport authority 2).

“We have also drawn up a quality agreement, which is primarily concluded between the city and the provider […] The city checks whether the offered supply meets the demand, or whether it is possible to provide more or less than is being demanded, so that a system can really […] be a correct and important component of the transport system.” (Transport authority).

“The city wants to do a test phase first, where we said we would not do a test phase but start with a smaller system, which is more controlled and will then adapt it gradually to the demand.” (Responsible person for e-scooter sharing at municipality).

“The city has not yet seen an e-scooter here, because the city administration wants you to use the [existing public infrastructure of] mobility hubs, the city doesn’t want e-scooters to be parked in the whole city […].” (Transport company).

“A legal character would require a legal framework or contractual relationship […]. As a municipality we actually do not have any other means of action [other than the quality agreement, comment of the authors]. Maybe this is the first thing to do.” (Transport authority).

- (1)

- Non-involvement in the introduction of e-scooters;

- (2)

- Pro-active involvement in the introduction of e-scooters by negotiating balanced requirements;

- (3)

- Protective regulation setting strict and rather unattractive requirements.

4.2. Ideal Design of Electric Scooter Sharing

4.2.1. Challenges of Current E-Scooter Sharing System

“I think they complement each other absolutely perfectly. The e-scooter is actually designed for distances of one to two kilometers, three kilometers maximum. The e-bike is then more suitable for medium distances—let’s say three to five kilometers—in other words, it is actually a supplement that also serves different usage situations.” (Public policy manager of an e-scooter operator).

“Of course there will be problems on the cycle tracks and there finally, yes this innovation of this further means of transport on the cycle tracks that one must agree there naturally evenly also first with one another, thus both the one and the other, in order to understand evenly who may drive actually where.” (Bike traffic commissioner 3).

“I am not a fan of these systems […]. Every form of traffic needs its place, that is simply a fact. As far as e-scooters are concerned, honestly, whether they exist or not, it doesn’t change the fact that for every form of mobility in the city—and that’s where I see the e-scooter heading for the bicycle or moped or whatever you want to call it—you need their space. At the moment, the bicycle has very little room in the city, so the space has to be created somewhere else.” (Chairman of German Cyclist’s Association).

“How does it work from the provider’s side? They still have their own app. So now I ask you quite naively, for e-scooter providers the integration is actually a gain, so that they have a second channel, where the people end up, in the end exactly with the providers. Yes, okay. But the forwarding from the providers to public transport does not works, so to speak. (Business and product developer of public transport provider).

“In other words, public transport alone is not enough to convince people to leave their own cars behind. That is simply a fact. It needs a complementary offer of e-scooters, of bike sharing, of all sorts—ridepooling, ridehailing, car sharing. Everything is part of it, and only the overall offer is so attractive that the users actually do or do not buy their own car or get rid of their second car... Whatever. In other words, you can’t look at it in isolation, how many e-scooter rides are now replacing what, but I think it’s the sum total of all of this. So that’s one piece of the puzzle.” (Public policy manager of an e-scooter operator).

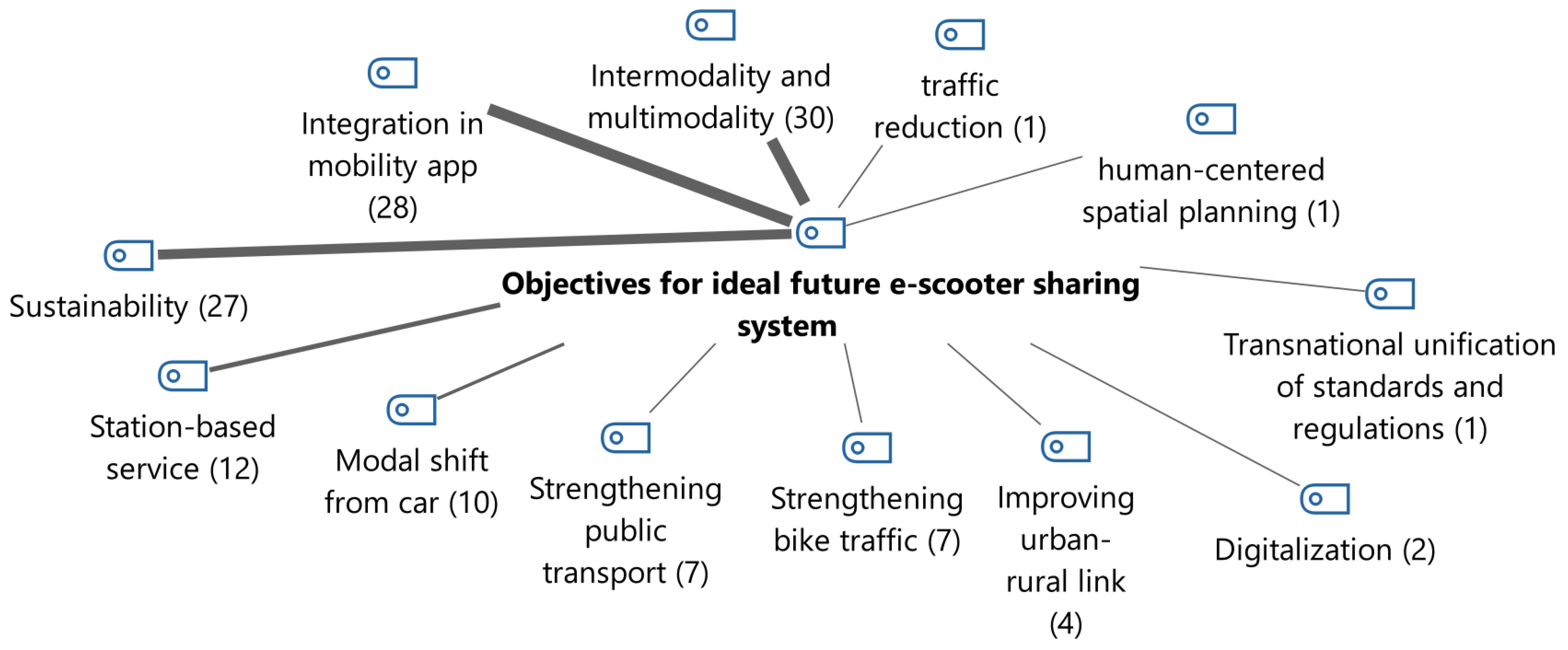

4.2.2. Requirements for an Ideal E-Scooter Sharing System

“So, I suppose that a mobility concept that is actually directed towards the future would be a decentralized one, with many transfer stations and decentralized offers. Information possibilities to know: When is the way with public transport shorter and faster? Or when is the fastest way by bicycle or with the e-scooter. Where are the nearest public rental services, whether they offer e-scooters or bicycles?” (Bike traffic commissioner 1).

“If I come from Poland, where the e-scooters are allowed to drive 28 km/h and you are only allowed to drive on the sidewalk and then come to Germany, where you are not allowed to do exactly that, then I think it is relatively complicated, also in terms of parking. And I think these are challenges, if you look at the whole thing a little bit on a European level, that you create more uniform rules, also to make it easier for users to follow the traffic rules.” (Public policy manager of an e-scooter operator).

“I think it’s a completely crazy idea. Yes, and I actually hope that the system does not survive, because it is just insanity to control such a vehicle physically.” (Bike traffic commissioner 4).

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Results

5.2. Derived Findings

- The German Personal Light Electric Vehicles Regulation creates suitable framework conditions for the introduction of e-scooter sharing systems.

- Transport authorities are hardly involved in the introduction of e-scooter systems.

- The introduction strategies do not foresee an integration of the new e-scooter sharing systems into the existing public transport systems but rather a co-existence of different systems.

- E-scooter sharing providers are aware of the fact that local quality agreements are not binding but they voluntarily adhere to the specific conditions to “maintain a friendly relationship with the cities” (area manager of an e-scooter operator).

- E-scooter sharing providers do not see a competitive situation between e-scooter sharing and public transport but aim to be integrated as a feeder system for the first and last mile. However, transport authorities and public transport providers question the possibilities of integration.

- The involvement of public transport companies and transportation authorities mostly takes places in form of consultation.

- E-scooter sharing operators do not see a competitive situation between their offer and bike sharing since they perceive that they complement each other due to the different trip lengths.

- The cooperation between cities regarding the topic of e-scooter sharing is rather rare and informal, which might impede collective learning.

- The integration of e-scooter sharing systems in the existing transport system and multimodal apps is a common goal of different stakeholders.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shaheen, S.; Totte, H.; Stocker, A. Future of Mobility White Paper. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68g2h1qv (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Kamargianni, M.; Li, W.; Matyas, M.; Schäfer, A. A critical review of new mobility services for urban transport. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 3294–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caspi, O.; Smart, M.J.; Noland, R. Spatial associations of dockless shared e-scooter usage. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 86, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, J.; Copeland, B.; Johnson, J.X. Are e-scooters polluters? The environmental impacts of shared dockless electric scooters. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 084031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Chow, J.Y.; Yoon, G.; He, B.Y. Forecasting e-scooter substitution of direct and access trips by mode and distance. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 96, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikka, N.; Vila, C.; Stratton, M.; Ghassemi, M.; Pourmand, A. Sharing the sidewalk: A case of E-scooter related pedestrian injury. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 37, 1807.e5–1807.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Z.; Cai, Q.; Xie, K.; Yang, D. Safety of micro-mobility: Analysis of E-Scooter crashes by mining news reports. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 143, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, O.; Swiderski, J.I.; Hicks, J.; Teoman, D.; Buehler, R. Pedestrians and e-scooters: An initial look at e-scooter parking and perceptions by riders and non-riders. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- City of Santa Monica. Shared Mobility Device Pilot Program Administrative Regulations. Available online: https://www.smgov.net/uploadedFiles/Departments/PCD/Transportation/SM-AdminGuidelines_03-05-2019_Final.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2021).

- San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Powered Scooter Share Permit Application 2019. Supporting Documents. Available online: https://www.sfmta.com/reports/powered-scootershare-permit-application-2019 (accessed on 29 July 2021).

- Gössling, S. Integrating e-scooters in urban transportation: Problems, policies, and the prospect of system change. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 79, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Byrnes, E.; McMahon, C.; Pontius, D.; Watts, J. Identifying Best Practices for Management of Electric Scooters. The Ohio State University. Available online: https://kb.osu.edu/bitstream/handle/1811/87590/AEDE4597_eScooterManagement_sp2019.pdf?seque (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Portland Bureau of Transportation. 2019 E-Scooter Report and Next Steps. Report. Available online: https://www.portland.gov/transportation/escooterpdx/2019-e-scooter-report-and-next-steps (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Gubman, J.; Jung, A.; Kiel, T.; Strehmann, J. E-Tretroller im Stadtverkehr Handlungsempfehlungen für Deutsche Städte und Gemeinden zum Umgang mit Stationslosen Verleihsystemen. Available online: http://www.staedtetag.de/imperia/md/content/dst/2019/agora-verkehrswende_e-tretroller_im_stadtverkehr_web.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2021).

- Hobusch, J.; Kostorz, N.; Wilkes, G.; Kagerbauer, M. E-Scooter–Freizeitspaß oder Alternatives Mobilitätsangebot? E-Scooter-Just for Fun or an Alternative Mobility Service. Straßenverkehrstechnik 2021, 1, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. The Stakeholder Concept and Strategic Management. In Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Hall, K.; Bordenkircher, B.; O’Neil, R.; Scott, S.C. Governing micro-mobility: A nationwide assessment of electric scooter regulations. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 98th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 13–17 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Smith, A.M.; Fischbacher, M. New service development: A stakeholder perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 1025–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, N.M.; Osman, H.; El-Diraby, T.E. Stakeholder management for public private partnerships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccarius, T.; Lu, C.C. Adoption intentions for micro-mobility–Insights from electric scooter sharing in Taiwan. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 84, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, A. Why will Micro Mobility Industry Make the Future? Available online: https://medium.com/@Splyt/why-will-micro-mobility-industry-make-thefuture-1b0a628ae3d0 (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Bai, S.; Jiao, J. Dockless E-scooter usage patterns and urban built Environments: A comparison study of Austin, TX, and Minneapolis, MN. Travel Behav. Soc. 2020, 20, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieliński, T.; Ważna, A. Electric Scooter Sharing and Bike Sharing User Behaviour and Characteristics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, G. Spatiotemporal comparative analysis of scooter-share and bike-share usage patterns in Washington, D.C. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 78, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allem, J.-P.; Majmundar, A. Are electric scooters promoted on social media with safety in mind? A case study on Bird’s Instagram. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 13, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, L.; Bergin, C. Impact of e-scooter injuries on emergency department imaging. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 63, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, C.S.; Schwieterman, J.P. E-Scooter Scenarios: Evaluating the Potential Mobility Benefits of Shared Dockless Scooters in Chicago; Transportation Research Board, Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; Volume 60422. [Google Scholar]

- Fitt, H.; Curl, A. E-Scooter Use in New Zealand: Insights around Some Frequently Asked Questions; University of Canterbury: Christchurch, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Angela-Curl-2/publication/333773843_E-scooter_use_in_New_Zealand_Insights_around_some_frequently_asked_questions/links/5d03179a4585157d15a95593/E-scooter-use-in-New-Zealand-Insights-around-some-frequently-asked-questions.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Mooney, S.J.; Hosford, K.; Howe, B.; Yan, A.; Winters, M.; Bassok, A.; Hirsch, J.A. Freedom from the station: Spatial equity in access to dockless bike share. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 74, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D.; Gebhardt, L.; Ehebrecht, D.; Lenz, B. Is micro-mobility sustainable? An overview of implications for accessibility, air pollution, safety, physical activity and subjective wellbeing. In Handbook of Sustainable Transport; Curtis, C., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 180–189. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, S.; Chan, N. Mobility and the sharing economy: Potential to facilitate the first-and last-mile public transit connections. Built Environ. 2016, 42, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, L.; Wolf, C.; Seiffert, R. “I’ll Take the E-Scooter Instead of My Car”—The Potential of E-Scooters as a Substitute for Car Trips in Germany. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnimhof, T.; Nobis, C. Mobilität in Deutschland–MiD. Ergebnisbericht. Report. Available online: https://www.bmvi.de/SharedDocs/DE/Anlage/G/mid-ergebnisbericht.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Arndt, W.; Hertel, M.; Langer, V.; Drews, F.; Wiedenhöft, E. Integration of Shared Mobility Approaches in Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning. European Platform on Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans. Report. Available online: https://difu.de/publikationen/2019/integration-of-shared-mobility-approaches-in-sustainable-urban-mobility-planning (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Zou, Z.; Younes, H.; Erdoğan, S.; Wu, J. Exploratory Analysis of Real-Time E-Scooter Trip Data in Washington, D.C. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, H.; Ma, Y.; Yang, D.; Hu, X.; Xie, K. Examining municipal guidelines for users of shared E-Scooters in the United States. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 92, 102710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection. Verordnung über die Teilnahme von Elektrokleinstfahrzeugen am Straßenverkehr (Elektrokleinstfahrzeuge-Verordnung-eKFV). Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ekfv/BJNR075610019.html (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Deutscher Städtetag. Nahmobilität gemeinsam stärken. Memorandum of Understanding 2. Zwischen Deutscher Städtetag, Deutscher Städte-und Gemeindebund und Anbietern von E-Tretroller-Verleihsystemen. Available online: http://www.staedtetag.de/imperia/md/content/dst/2019/mou_e-tretroller_dst_dstgb_final.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- City of Dusseldorf. Musterentwurf einer Sondernutzungserlaubnis. Bereitstellung von Gewerblichen Verleihsystemen für Leihfahrräder/E-Scooter/Elektroroller in der Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf. Amt für Verkehrsmanagement und Verkehrsregelung (Anlage 2 zur Vorlage OVA/030/2019). Available online: https://www.duesseldorf.de/medienportal/sitzungen/?L=0 (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- City of Munich. Selbstverpflichtungserklärung der E-Scooter-Verleiher. Available online: https://www.muenchen.de/rathaus/dam/jcr:4f1d3f55-078b-4c9c-8cbe-94b416cc15be/Freiwillige%20Selbstverpflichtungserkl%C3%A4rung%20EKF-Sharing%20LH%20M%C3%BCnchen_Stand%2006.06.2019.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Gubrium, J.F.; Holstein, J.A. Forms of Interviewing. In Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 55–176. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, E.C.; Worth, A. The use of the telephone interview for research. NT Res. 2001, 6, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriball, K.L.; Christian, S.L.; While, A.E.; Bergen, A. The telephone survey method: A discussion paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 1996, 24, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherf, C.; Knie, A.; Pfaff, T.; Ruhrort, L.; Schade, W.; Wagner, U. Mobilitätsmonitor Nr. 9.-November 2019. Int. Verk. 2019, 71, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tack, A.; Klein, A.; Bock, B. E-Scooter in Deutschland-Ein Datenbasierter Debattenbeitrag. Available online: http://scooters.civity.de/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- City of Hanover. E-Scooter in Hannover: Mit Rücksicht Nutzen! Available online: https://www.hannover.de/Leben-in-der-Region-Hannover/Mobilit%C3%A4t/Verkehrsplanung-entwicklung/Elektromobilit%C3%A4t/E-Scooter/E-Scooter-in-Hannover-Mit-R%C3%BCcksicht-nutzen (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Behrens, N. Nun stehen die E-Scooter in Wolfsburg Bereit. Wolfsburger Nachrichten. Available online: https://www.wolfsburger-nachrichten.de/wolfsburg/article228623731/Seit-Donnerstag-stehen-die-E-Scooter-in-Wolfsburg-bereit.html (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- City of Wolfsburg. E-Scooter in Wolfsburg.Homepage City of Wolfsburg. Available online: https://www.wolfsburg.de/leben/mobilitaetverkehr/e-mobilitaet (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Stachura, J. 300 Zusätzliche Leih-Scooter in Braunschweig. Available online: https://www.news38.de/braunschweig/article229662542/Braunschweig-E-Scooter-ausleihen-Lime-Tier.html (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- City of Brunswick. E-Tretrollersharing/E-Scootersharing. Available online: https://www.braunschweig.de/leben/stadtplan_verkehr/sharing_Angebote/e-tretrollersharing.php (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- City of Berlin. Senatsverwaltung Erlässt neue Regelpläne für das Parken von Lastenrädern und E-Tretrollern. Available online: https://www.berlin.de/sen/uvk/presse/pressemitteilungen/2019/pressemitteilung.863628.php (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2020; VERBI Software: Berlin, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis. In A companion to Qualitative Research; Flick, U., von Kardoff, E., Steinke, I., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Reinbek bei Hamburg, Germany, 2004; pp. 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rhein-Main-Verkehrsverbund. Verbundweiter Nahverkehrsplan für die Region Frankfurt Rhein-Main. Available online: https://www.kelkheim.de/_data/19_11_13_RNVP_Entwurf_final_mit_Anlagen.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Turoń, K.; Czech, P. The concept of rules and recommendations for riding shared and private e-scooters in the road network in the light of global problems. In Scientific and Technical Conference Transport Systems Theory and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Turoń, K.; Kubik, A.; Chen, F. Electric Shared Mobility Services during the Pandemic: Modeling Aspects of Transportation. Energies 2021, 14, 2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.-H. User Behavioral Intentions toward a Scooter-Sharing Service: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, G.; Arsenio, E.; Ribeiro, P. The Role of Shared E-Scooter Systems in Urban Sustainability and Resilience during the COVID-19 Mobility Restrictions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almannaa, M.H.; Alsahhaf, F.A.; Ashqar, H.I.; Elhenawy, M.; Masoud, M.; Rakotonirainy, A. Perception Analysis of E-Scooter Riders and Non-Riders in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Survey Outputs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Introduction Style | Protective | Pro-Active | Laissez-Faire |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market entry | No market entry after rejection | Market entry with conditions | Free market entry without conditions |

| Responses to operators | Hesitating | Open | Ignorant |

| Regulation strategy | Strict requirements/protective regulations | Negotiating balanced requirements/pro-active involvement | Non-involvement |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

König, A.; Gebhardt, L.; Stark, K.; Schuppan, J. A Multi-Perspective Assessment of the Introduction of E-Scooter Sharing in Germany. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052639

König A, Gebhardt L, Stark K, Schuppan J. A Multi-Perspective Assessment of the Introduction of E-Scooter Sharing in Germany. Sustainability. 2022; 14(5):2639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052639

Chicago/Turabian StyleKönig, Alexandra, Laura Gebhardt, Kerstin Stark, and Julia Schuppan. 2022. "A Multi-Perspective Assessment of the Introduction of E-Scooter Sharing in Germany" Sustainability 14, no. 5: 2639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052639

APA StyleKönig, A., Gebhardt, L., Stark, K., & Schuppan, J. (2022). A Multi-Perspective Assessment of the Introduction of E-Scooter Sharing in Germany. Sustainability, 14(5), 2639. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052639