Abstract

The role of local food products in the food system of West European countries tends to increase. Currently, the economic aspects of food in most of the western world are no longer dominant in decision-making, and consumers are willing to pay more for prosocial food. The present research examines support for prosocial food among consumers in Latvia. A consumer survey conducted in Latvia (n = 1000) revealed attitudes and behavior in relation to: (a) food and shopping convenience values; (b) economic values; (c) prosocial values of food consumption (local and environmental friendly food). The purpose of the survey was to make quantitative measurements that reveal the main trends in the society of Latvia and what values are important for consumers, depending on their family status, level of education, place of residence and income level. The scientific discourse reveals that more support for prosocial food is observed among higher-income households living in a city which have children and higher education. Surprisingly, the research results did not confirm this. Although the support of this consumer segment for such food is relatively high, it is lower than that of other consumers. Perhaps the explanation should be sought in the broader context of life values, e.g., sentimental feelings caused by travel rather than belongingness to a particular place; or, it is possible that hedonism prevails in the awareness of social and ecological reality and each person’s responsibility for it, which could be further research problems.

1. Introduction

The food system is critical to human existence and its quality, while at the same time making a significant impact on ecosystem services, thereby causing significant damage. In response to these challenges, EU politicians call for common goods to be viewed as consumer goods, emphasizing the role of the food system in environmental, social and economic sustainability [1]. At the same time, this document states that it is local food initiatives that can play a key role in achieving this goal. It is clear that viewing food only in the context of the circulation of nutrients or the nutrient supply function of humans is too narrow a perspective and means ignoring the existing reality. Therefore, researchers seek to find different contexts that better describe the need to transform the food system. A short supply chain is a supply chain involving a limited number of economic operators committed to cooperation, local economic development and close geographical and social relations between producers, processors and consumers [2]. On the one hand, the local food system can be seen in terms of economic production and consumption, which includes production, processing, marketing, distribution and consumption, with the participation of local actors. In this case, the development of the local food system is linked to the challenges of the circular economy [3]. The importance of local food also increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, when global food chains were facing difficulties and the local food system played a key role in agricultural sustainability and food security [4], although the price effect of COVID-19 restrictions was relatively small [5]. On the other hand, the local food system can be seen in the broader context of non-food supply. Its development is determined by essential drivers: the ability to integrate and interact with the local social system and to ensure harmony with ecosystem services and with local culture and traditions [6]. Cultural aspects play an important role in the development of the local food system, while economic aspects remain the most important, despite the growing interest among producers and consumers in environmentally friendly food [7]. The development of food consumption is related to the development of values in society because values determine the attitude that influences the goals set and the behavior to achieve them. The importance given to food by the consumer also determines the expected satisfaction with the product chosen and consumed [8]. Moreover, the consumer does not just represent the demand in the consumer market but also the demand in the social agenda. These are probably the main reasons why consumer attitudes are not only practical marketing issues but also play a role in the scientific debate, both in terms of understanding human behavior and in terms of sustainable development. The present research seeks to emphasize the role of food consumption by focusing on the values that food could be associated with. Similar research studies focus on the role of hedonic traits in relation to consumption [9], the influence of food values on loyalty [10,11], as well as many other aspects.

The present research analyzes consumer behavior and local food development based on a population survey. The aim of the research is to determine the values of consumers and their impact on the development of the local food system. The specific objectives are: (i) to identify the factors influencing the choice of consumer values and behavior in the market that appear in the scientific discussion; (ii) to identify the Latvian population’s ratings of statements that express a certain position on the values related to (a) basic properties and ease of purchase of food, (b) economic factors in food consumption and (c) prosocial values of food consumption (local and environmental-friendly food); (iii) to determine the impact of socio-economic characteristics on the assessment of consumer values. Surprisingly, a hypothesis put forward—that households with children living in urban areas and earning relatively high incomes choose pro-social food—did not prove to be true, allowing for researchers to ask more precise questions for further research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Food and Values

In modern Western society, food is not just a basic necessity needed for biological existence, it is associated with a complex set of assessments that are subjective but at the same time influence social behavior in a densely populated area. In the context of the mainstream economy, this is a subjective assessment of utility that influences market behavior, which in turn affects the supply side (see the next section). At the same time, it is often not just a question of market behavior but of the behavior of a wider social group. According to the Value Belief Norm Theory [12], altruistic, egoistic, traditional and openness to change values create a new ecological paradigm that affects awareness by creating changes in personal norms both in the social and the private spheres. For the consumer, according to this theory, food represents certain values and belongingness to a certain social group. Of course, pro-environmental behavior patterns are complex and could be significantly influenced by contextual conditions [13,14]. Sometimes, it is not possible to define the most important value that determines a pattern of behavior. For example, consuming less meat could be attributable to both a concern for the environment and a concern for personal health. It is no surprise that egoism or a concern for health dominates. However, when choosing healthier food, consumers themselves do not consider the meaning of healthy food to be the most important thing but rather subordinate it to the moral meaning of food (act in accordance with the idea of good human behavior) [15]. Interestingly, the same moral meaning of food is also important when it comes to shopping in small shops, buying local products, not consuming meat and prioritizing quality over quantity; it basically matters how trendy it looks [16]. The prosocial behavior of consumers (participation in voluntary work, cooperation, donations or purchases of products generating some social benefit) becomes increasingly popular. Consumers who choose prosocial food (e.g., fair trade, local, climate-friendly, etc.) are also the most likely to buy organic food, which is a positive fact for retailers, the country and the whole world. At the same time, this could lead to a certain segmental contrast between prosocial and conventional food [17]. Research results suggesting that organic food users are more prosocially motivated are ambiguous. For example, a research study [18] found that organic food users were less willing to engage in supporting unfamiliar poor people and that they were significantly more severe in moral judgments. On the one hand, this could be attributed to the fact that, in some cases, specific food choices, e.g., organic food, are based on the population’s desire to belong to a group (e.g., luxury or trendy consumers), without related environmental or other prosocial motives. Or, the motive of consumer behavior is only a concern for nature; yet, humans are the cause of harm to nature and deserve a critical attitude taken towards them. However, it is clear that the German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach’s famous saying from his essay Concerning Spiritualism and Materialism (1863), “you are what you eat”, takes a broader view. Not only does food affect our mood but we choose food according to our mood and perception of life.

2.2. Local Food and Inferior Goods (Utility Perspective)

Economics refers to inferior goods, which are defined as goods whose demand decreases with an increase in the consumer’s income. Basically, inferior goods are those that can be used relatively easily (cheaply) to meet basic survival needs. In this case, the utility of a good is relatively high, as is the income elasticity of demand for it. As income increases, the buyer is ready to quickly change the previous buying habits in favor of goods of higher utility. Overall, food has traditionally been considered to have inelastic demand due to its importance for household consumption, while an extremely high supply of food in the market forces consumers to make choices about a particular good. The question of consumer choice criteria is important, i.e., which criteria—economic, social and environmental—are important to the consumer’s rating of utility?

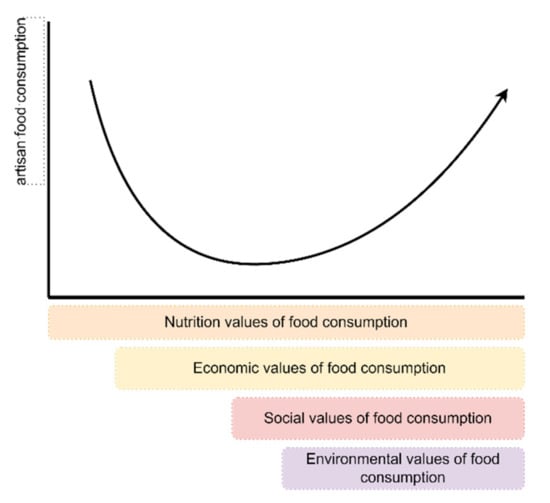

Inferior goods are characterized by the fact that they are relatively simple, often of local origin and needed to meet the so-called basic needs, and food provides nutrients for the human organism. The indigenous nature of such goods could be characterized by their relatively low price, which protects against a high level of competition. However, the very nature of such goods might also be the reason why unprocessed food is usually of local origin. It could be reasonably assumed that: (a) goods are fresher due to the shorter transport route; (b) varieties or species of food ingredients are typical of the local, customer-accepted cuisine; (c) there is greater certainty in relation to the origin of the goods and their production and processing technologies; (d) there is an emotional connection with the national product as “one’s own” versus “from the outside”. There is some contradiction: although inferior goods are inelastic in demand, they might have a certain value, which increases their utility and thus increases their elasticity, which could mean that goods of domestic origin have a higher price than those imported from abroad. At least in the case of Latvia, this is obvious [19]. A hypothesis could be put forward that, as society develops, it consumes more goods of prosocial value, while maintaining interest in relatively simple, unprocessed goods of known origin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Artisan food and values.

Increasing the quality of food, which involves processing, inevitably raises the price, which is an essential precondition for the competitiveness of imported food that significantly increases competition through supplying a variety of goods of relatively high quality with relatively many added values such as a lower GHG emission footprint, fair trade, sustainability certificates, etc. In this part of the market segment, locally sourced foods often lose their importance, their elasticity decreases and consumers choose foods relatively easily without paying much attention to their origin. At the same time, it is a more important segment of the food market, which provides most of the everyday food basket. What matters is the “future survival” of local food and consumer decisions that influence their choices and decisions to return to the local food. In this context, different patterns of expectations [20,21,22] and the possibility of comparing consumer expectations with the reality after consuming the product are important. If the reality is better than expected, the customer will return and buy the product again, but if the expectation is not actually met, the buyer will look for an alternative product in case of this negative confirmation.

Each region has its own specific products, which are expensive and represent a relatively small proportion of daily consumption. In addition to such products, social, cultural and environmental values are also important for the diversity of nutrients and foods in everyday consumption. Food and drink have traditionally been part of the code of sacred values for many nations, including Latvians. Cultural traditions are also a factor influencing the eating habits of modern people [23]. The annual nature cycle (e.g., cumin cheese—a component of traditional holiday cuisine) is important for the consumption of only locally available products that are not offered by global food chains. The demand for such products is extremely inelastic (at least over some period), resulting in a relatively low demand and a relatively high price. In addition to the segment of inferior goods, this segment is also suitable for local food chains. At the same time, producers need to reckon with a seasonal, relatively low demand, with no significant growth potential. Medium-sized enterprises often do not consider it important to supply such products, which requires the readjustment of their production lines; therefore, there is a growing interest in this segment from home producers who provide traditionally recognizable or specific products.

2.3. Factors Influencing the Behavior

The topicality of values changes due to various factors. The effect of income elasticity on utility assessment was already mentioned above. At the same time, the classical economy is unable to respond to the actions of a large number of economic entities that make seemingly “illogical” decisions. To explain this, it would be necessary to realize that the individual, in particular the consumer, is not a logical decision-making machine, or, more precisely, the horizon of decision-making logic often goes beyond the perception of the factors influencing a particular issue. An explanation is an awareness that human behavior is determined by evolutionary factors. Humans are biological beings who primarily value the ability to pass on their genetic information through children. One of the most popular ideas about the dominance of this function in human behavior is Richard Dawkins’ idea of the Selfish Gene, which states that the motive for human action is determined by competition, natural selection and the replication of the most appropriate genes essential for survival [24]. On the one hand, such a view of economic processes is also in line with the basic classical postulates of economics about an economic individual. On the other hand, rational behavior means to take care of children more than of one’s own personal existence. This apparent altruistic behavior is essentially based on rational behavior and is fundamentally consistent with the goal of maximizing utility [25]. It would be logical to assume that people with children value utility differently, thereby broadening the scope of their assessment. Children, as decision-makers, are not homogeneous concerning their influence on their parents or their role as buyers. Interestingly, the age of children is important; for example, there are statistically significant differences in the consumption of organic fish by families with children under five years of age [26]. It could be assumed that parents take special care of their children, trying to provide them with the best food possible, depending on their understanding and abilities. At the same time, children are not only passive factors influencing consumption decisions. It is at a relatively early stage that children themselves begin consuming various information channels that affect their role in the shopping process [27]. Children can significantly influence parental choices [28]. At the same time, not only does the child’s own existence need to be taken into account but also other factors such as parental demographics (family type, maternal employment status), socioeconomic status, the peculiarities of family communication, child demographics (age, number of children, gender) and the product type [29].

Assuming that the choices of goods are rational, which has been doubted many times today [30], limited rationality explains the purchase of goods as a cognitively emotional process that does not lead to a rational choice of goods. Accordingly, to reap the maximum benefit of food consumption, it is necessary to consciously analyze the current situation and realize the predefined values, which is basically a kind of function of maximizing utility. This means, on the one hand, to significantly limit, in Kaneman’s [31] terminology, the operation of System 1 (automatic, fast, unconscious control) by contributing to the operation of System 2, which requires more cognitive efforts and concentration. On the other hand, conscious or mindful consumption itself is only an instrument that does not contain the attributes of assessment or decision-making. Before making consumption decisions, as suggested by the Value Belief Norm Theory discussed above, it is necessary to choose values whether they are hedonic or altruistic. It is possible to apply not only individual values but also whole value systems, such as religions or secular philosophical systems. Sabrina Helm and Brintha Subramaniam suggest [32] the concept of mindfulness borrowed from Eastern religious-philosophical systems and apply a social context to create socio-cognitive mindfulness as opposed to materialism. The mentioned authors have concluded that mindfulness and sustainable consumption are interrelated; yet, it should be noted that mindfulness is a religious and ethical concept that influences the person’s overall worldview. There is a growing movement in favor of conscious consumption, which aims to increase public awareness of purchasing decisions, taking into account the health of the consumer as well as the environmental and social aspects.

The availability of relevant information is an essential precondition for informed decision-making. Along with other aspects related to food, knowledge about healthy, ethical and resource-intensive food consumption becomes increasingly important nowadays [33].

In the case of food, the most important information is provided by labels. The EU prescribes the content and amount of information [34] that needs to appear on the packaging of goods. However, most food producers do not limit themselves to the prescribed information, recognizing that it is a means of communication with the consumer. Social media communication with the public is the norm today; bloggers on YouTube and Twitter and various other bloggers publish daily news about food, the origin of food, the production process and what food is and is not safe. The public consumes this information without drawing a line between opinions, facts, true information and fiction. In some cases, consumers choose not to know the information that indirectly indicates the negative effects of consuming the desired food (calories in sweets, carcinogens, etc.) [35]. However, the availability of information undoubtedly affects the ability of consumers to increase their wellbeing; although, in some cases, the consumer lacks the wish, possibility and time to analyze the information—for example, on the effects of specific chemical additives [35].

3. Materials and Methods

A representative survey of Latvia’s population on food consumption habits and the role of local food was conducted to collect empirical data on consumers’ behavior and the values important to them in relation to food. The purpose of the survey was to make quantitative measurements that reveal the main trends in the society of Latvia and what values are important for consumers, depending on their family status, level of education, place of residence and income level. The researchers put forward a hypothesis that there were significant differences between various socio-demographic groups in their orientation towards different food values.

The survey included three latent constructs: food and shopping convenience values, economic and locally produced values and environmentally friendly (prosocial) food values. The survey included a total of 15 items: four relating to the construct of “food and shopping convenience values”, five representing the construct of “economic values” and six pertaining to the construct of “locally produced, environmentally friendly (prosocial) food values”.

The researchers considered the Likert scale to be the most appropriate scale for measuring the items, which allowed them to obtain quantitative information about the different opinions and attitudes of the respondents and identify the interrelationships [36]. The research used an asymmetric four-point Likert scale, which required the respondents to indicate the extent to which they agreed with a particular statement (item). On the scale, 1 means that the respondent agrees with the statement, 2—rather agrees, 3—rather disagrees and 4 indicates that the respondent does not agree with the statement. In addition, an alternative reply option, “I do not know/cannot answer”, was provided outside the scale, which was not included in the data processing.

In the representative survey sample, 1000 respondents from the Latvian population older than 18 years were included. The data were collected in cooperation with the research center SKDS via phone interviews (CATI) in December 2021. The length of the interviews was 20 min, and all respondents were informed about the research aim.

The respondents were selected randomly, and the data obtained were weighted according to the following variables: the region, gender, nationality and age, taking into account the proportions of the population. The sample represented 46.1% men and 53.9% women; 58.9% were Latvians and 41.1% represent other nationalities.

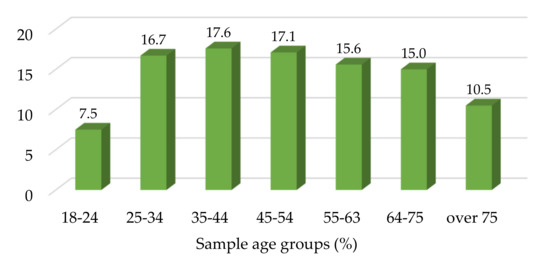

In addition, the proportions of the general population of Latvia were observed in the sample in relation to different age groups (Figure 2) and the region represented (Figure 3): 33.5% of the respondents were from Riga (capital city), 19.1% from Pieriga, 9.6% from Vidzeme, 12.4% from Kurzeme, 11.7% from Zemgale and 13.7% from Latgale. 33.5% of the respondents represented cities, while 37.7% were residents of small towns and 28.8% were representatives of rural populations.

Figure 2.

Sample age groups, n = 1000.

Figure 3.

Regions of Latvia [37].

For the research, it was important to indicate whether consumers’ behavior and at-attitudes towards local food differed based on the fact that respondents had small children. Therefore, people were asked to indicate whether they had children under the age of 18. 15.1% of the respondents admitted they had one child, 18.9% noted they had more than one child and 66.0% of the respondents stated that they had no children under the age of 18.

For measuring the internal consistency of the items, Cronbach’s alpha has been calculated. For an in-depth measurement of the differences in opinions, the survey data were tested for compliance with a normal distribution. Therefore, for the subsequent data processing, the differences between the two groups were measured by doing an independent samples t-test, and the differences between the different groups were measured by performing a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical test calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23 software. Average values, standard deviations and p-values (significance level: 0.05) were calculated to interpret the results of the statistical tests. The minimum mean value was set at 1 and the maximum one was 4, where a value near 1 indicated high agreement with the statement and a value near 4 indicated low agreement with the statement. The standard deviation was used to identify the stability of the mean value, which indicated the consensus of opinions or, on the contrary, their variance. In interpreting the results, the researchers considered that standard deviation values up to 0.99 indicated a relatively low variance and consensus of the respondent opinions, while the values above 1 indicated a high variance of opinions. p-values were used to measure group differences: if it was higher than the significance level of 0.05, there were no statistically significant differences between the opinions of different groups, while, if it was lower than the significance level of 0.05, it could be concluded that the opinions of different groups differed in a statistically significant manner.

The research team followed the guidelines of the research ethics: any biased attitudes, discrimination and potential harm to the respondents was avoided, informed consent from the respondents was received and the principle of equality to all target groups during the data gathering and data analysis process as well as the informants’ privacy and anonymity were ensured.

Brief Context in the Case of Latvia

Latvia is one of the Baltic countries in Northern Europe with a population of nearly 1.9 million (62.7% are Latvians, 24.5%-Russians and 12.8% represent other ethnic groups) [38]. In 2021, 31.8% of the total population lived in the countryside. Rural depopulation, however, is gradually increasing each year because of out-migration, the lack of important infrastructure and services in rural municipalities and adverse demographic processes such as ageing and low birth rates [39]. Yet, an interesting but not widespread trend of counterurbanization can be observed: people who follow greener lifestyles and young families with children move from urban areas to the countryside, thus revitalizing rural communities [40]. Members of these households often both work and earn an income in cities where they are significantly higher (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Composition of disposable income of Latvian households on average per household member (EUR per month) [38].

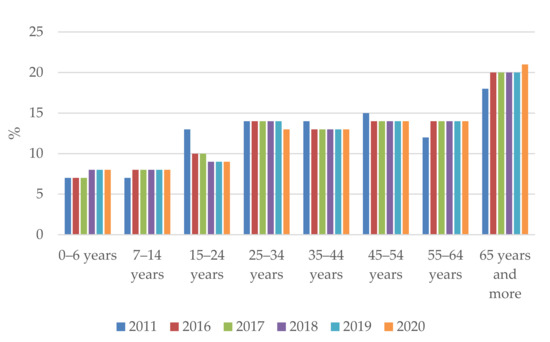

In urban areas, the household income in 2021 was EUR 630.04 per household member, while in rural areas it was EUR 573.24. Of course, such a distribution is not unique to Latvia, which can be explained by economic intensity, economic complexity in cities and natural constraints in the diminishing return sectors (agriculture, forestry) in rural areas. The majority of Latvian households are without children (72.8% in 2020), while only 3.6% of households had 3 or more children. It should be noted that, in the research survey, the share of households without children was 66.0% and 18.9% more than households with one child. The relatively small proportion of households with children can be explained by the age structure of the population. The average age of the Latvian population is increasing (Figure 5), which is related to both the increase in the quality of life of the population and the decrease in the birth rate.

Figure 5.

Proportion of population by age groups in Latvia [38].

More than a fifth (21%) of the population is over the age of 65 (Figure 2), which roughly corresponds to the sample in the survey. The number of young people has stabilized after a sharp decline since 2011. The proportion of young respondents in the survey is lower, which can be explained by the smaller (but increasing, as discussed in the literature review) role of buying products in the process.

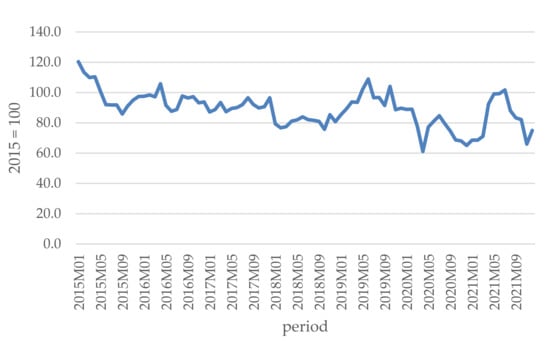

As a member state of the European Union (EU), Latvia follows all EU policy guidelines related to the Common Agricultural Policy, the Green Deal and sustainable development goals including food production and consumption. The Bioeconomy strategy 2030 in Latvia emphasizes the need for a greener economy and production, consumer education in terms of more responsible food consumption and reducing food waste, innovative local food products and investment in food production including organic farming [41]. Recent studies witness that people in Latvia, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, have started to pay more attention to their food consumption habits including healthy diets and locally produced food. People in Latvia have become more aware of food waste, food safety and the environmental impact related to the food production [42]. At the same time, consumers are visiting city markets and trade stands less and less (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Total turnover indices of retail trade enterprises in stands and markets [38].

The total turnover indices on trading stands and markets are declining. This could be attributed to two factors. First of all, the concept of market development is outdated (i.e., the market as a place to buy simple products; on the contrary, a market is a place to buy specific products with leisure and education services and integrated tourism). Secondly, it could be attributed to the obsolete and unattractive infrastructure in many places. Artisan food is a very special niche that also is popular in Latvia. A number of online sites provide information and opportunities to purchase local artisan food products (e.g., [43]). Latvians like to use it, and shopping in online stores is growing, for which only one of the factors influencing motivation was the COVID-19 pandemic [44]. This study is devoted to discovering and discussing other factors influencing consumer behavior that are unclear.

4. Results

It was important to analyze household food shopping habits in three dimensions: attitudes towards the food and shopping convenience value, attitudes towards economic factors and attitudes towards the value of locally produced, environmentally friendly food. The issues were analyzed according to the population’s incomes, places of residence (rural/urban), levels of education and the number of children in the families. In the authors’ opinion, these factors provide a superficial but sufficient basis to consider the differences in shopping habits across different population segments.

4.1. Food and Shopping Convenience Values

As previously discussed, the primary function of food is to supply nutrients to the human organism. From the perspective of both economic utility and prosocial values, it is important that the food purchased is consumed, as it ensures both the efficient use of economic resources (including personal finances) and causes less damage to the environment and climate. Four potential sub-factors that indicate consumer behavior were put forward: (a) all the necessary food can be bought in a supermarket; (b) it is important to trust the seller when purchasing food; (c) home-produced local food is as safe as industrially produced food; (d) the best of each region of the world needs to be chosen. The respondents were asked to give ratings to the statements (agree—1, rather agree—2, rather disagree—3, disagree—4). The data obtained were collected and analyzed based on the above characteristics, and the differences in ratings were identified by performing a one-way ANOVA test; the results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondent opinions on food and shopping convenience.

In Latvia, the consumers were most likely to buy food in supermarkets, while leaving the option to buy food elsewhere. The average rating by the respondents (n = 988) given to the statement “you like to buy all the food in one place, like a supermarket” was 2.15 (rather agree). There were no statistically significant differences in opinions (p-value = 0.105). Similarly, the number of children in the consumer household had no significant effect (p-value = 0.316) on the rating of the statement “communication and personal contact with the food producer is important for you”. It should be noted that such a personal relationship with the seller was not very important; the average rating was 2.84 (rather disagree), which is not surprising considering that most food consumers were ready to buy food in the supermarket and taking into account the rather introverted nature of Latvians. The consumers were quite convinced (average = 1.64) that food artisans were able to meet hygiene requirements and that the food was safe for consumption; the consensus on this issue was not affected by the number of children they had. However, the ratings of the statement “choose the best diet from each region of the world” given by households with children were slightly more positive (average = 2.51) than those given by households without children (average = 2.73), as evidenced by the p-value of 0.01. It is possible that the ratings were influenced by the parental care for children mentioned in the previous theoretical discussion, emphasizing that they would rather give the best possible food to their offspring. At the same time, agreeing with this statement is ambiguous. It indicates that that any of the following statements could provide a more complex set of values expected by consumers in Latvia. It is possible that there were no significant differences in the distribution of respondents by level of education in relation to basic shopping factors. Most of the respondents had higher education, followed by those with secondary vocational and secondary education. Somewhat surprisingly, there were no significant differences in shopping habits, depending on household income. There were some differences if analyzed by the place of residence of the respondents. It was more important for rural residents to have contact with the salesperson (average = 2.63) than for those living in a metropolitan area (average = 2.97), which could be explained by a smaller community in which they were more likely to be familiar with one another. At the same time, although the differences were significant (p-value = 0.00), overall, the possibility of communication was not very important to shopping for food. Rural residents were also more confident (p-value = 0.024) about the compliance of local artisan food with hygiene requirements (average = 1.53), while urban residents (average = 1.70) and metropolitan residents (0.024) were slightly more critical. Rural residents themselves or their relatives were often involved in the production of such food, which increased their confidence in the food quality.

It was useful to examine the influence of complex factors on the rations of statements for each dimension. Based on the theoretical discussion, the research suggested that the differences could be identified by analyzing the opinions of households with children, high incomes and higher education living in cities. Therefore, the research placed a special focus on whether the opinions of the respondents corresponded to the characteristics of this segment. No significant differences were expected with regard to the statements of the first dimension because, overall, there were no differences in opinions; however, the research also performed a complex analysis of the statements of this dimension (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Opinions on food and shopping convenience among respondents with special characteristics.

As expected, no significant differences in opinions were observed between the segment “households with children, high-income and higher education living in cities” and other buyers. The only statement whose p-values (Independent Samples t-test) showed differences was that regarding the role of communication in shopping. For this segment, communication was quite insignificant (average = 3.0), whereas for others it was a little more important (average = 2.81).

4.2. Economic Values

Economic values show the respondents’ desire to, on the one hand, purchase food at the lowest possible cost and, on the other hand, to benefit indirectly from the consumption of food through the multiplier effect of consumption of local food, increasing the wellbeing of the local community and increasing employment. The differences in incomes and education levels, places of residence and number of children were examined in the same way as for the statements of the previous dimension (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respondent opinions on economic values.

Small differences (p-value = 0.052) were found for consumers with children (average = 2.25) in relation to the statement “when buying food, your main focus is on price” compared with other consumers (average = 2.14); however, the differences were not very large and, overall, families with children more carefully considered the costs. Overall, consumers in Latvia were positive about the possibility of indirectly influencing local economies through food choices. Quite unanimously (p-value = 0.962), the population were positive (average = 1.80) about the statement “you buy locally produced products to support local producers”. There was an even greater consensus on the statements “local food production contributes to prosperity of the country/region” (average = 1.51) and “local food production consumption creating more jobs” (average = 1.41). No significant differences in opinions were observed for the two statements depending on the number of children in the household. There were differences in opinions in relation to the distribution of respondents by level of education for the statement “when buying food, your main focus is on price” (p-value = 0.000). Buyers with a lower level of education were more likely to agree with this statement (average = 2.00) than those with a higher level of education (average = 2.36). This is relatively easy to explain, as individuals with higher education earn significantly higher wages, which increases their ability to buy more varied food, as noted in the previous discussion on increasing income elasticity. The respondents were positive about the other statements concerning supporting local producers and promoting prosperity and job creation and appreciated the opportunity to promote the producers through their food choices. As noted above, the level of education could be quite easily linked to income, so it is not surprising (p-value = 0.000) that consumers with an income below EUR 300 per household member paid much more attention to price (average = 1.79) than those with an income above EUR 800 per household member (average = 2.72). It is quite safe to say that price for the wealthiest residents is just one of the factors influencing their choices. Prosocial values are important, such as support for local culture and the preservation of the environment; yet, this relates to the next dimension. There was no significant difference in terms of residence, which was a positive fact, as relative wellbeing (at least in relation to food choices) was not affected by food prices (p-value = 0.355) and it was a significant (average = 2.19) but not dominant choice factor. In contrast, there was a difference in opinions (p-value = 0.003) about the statement on support for domestic producers. Rural residents were more willing (average = 1.62) to support local producers than the metropolitan population (average = 1.90). This could be easy to understand, given that local communities are more subject to competition challenges for local food. There are no significant differences in opinions about the statements on prosperity and employment, although both statements were supported and the choice factors were significant.

After analyzing the specific segment “a family living in the City with children and higher education” (Table 4), it should be noted that the most significant differences in opinions were found for the statement on the role of prices (p-value (Independent Samples t-test) = 0.003). In this case, for the specific segment (average = 2.44), price was a less important factor in food choices than for other respondents (average = 2.16). The mentioned households noted a strong link between local food choices and local job creation, while, for other respondents, it was not significant.

Table 4.

Opinions on economic value among respondents with special characteristics.

4.3. Prosocial Values

The statements of the third dimension relate to sentimental feelings about the local community, its traditions and its environment. The food consumed also expresses the attitude towards the world around us, as choosing it can indirectly express support for the values that are important to consumers themselves. Positive, non-aggressive patriotism is important because it is one of the elements that integrates the state and the community. Preserving the value of the environment is undoubtedly a more productive and effective form of patriotism because, by preserving the environment, we provide basic ecosystem services for next generations, which is a basic precondition for the existence of the state. This dimension includes six statements—four on the choices of local food and two on the choices of environmentally friendly food (which includes both organic and low-carbon, labeled for various sustainability certificates). One of the statements relates to reaping a benefit (“it is important for you that the food is produced in an environmentally friendly way”), while the second represents a loss (“you would be willing to give up a favorite product if you knew that it was not environmentally friendly”). The consumer often shows support for various prosocial values, especially if nothing is lost. The formulation itself is also important—it needs to reflect a situation where respondents value “willingness to pay” more than “willingness to accept”, which has also been proven in research studies [45], as well as to explain the already well-known Tversky and Kahneman [46] “Loss aversion” situation. This was also the case (Table 5).

Table 5.

Respondent opinions on prosocial values.

Referring to the above-mentioned idea, which does not correspond to the order in the table, the statement “it is important for you that the food is produced in an environmentally friendly way” had relatively reliable support regardless of the characteristics of the respondents, and three of the characteristics did not affect the respondent choices. The number of children did not influence (p-value = 0.480) the choice of environmentally friendly food (average = 1.82). Similarly, income levels and the place of residence did not affect the generally high support for the statement that food should be produced in an environmentally friendly way. However, it is surprising that the level of education affected the level of support. In this case, it is not the characteristic itself that is surprising, which was previously discussed in connection with deliberate purchases, but rather the results. Consumers with secondary (average = 1.62) and basic education (average = 1.69) expressed significantly (p-value = 0.003) higher support than those with higher education (1.90). Although overall the respondents acknowledged that it was an important factor in their food choices, it might seem that better educated people or people with children were more concerned about the environment. It is possible that the information channels used by consumers with basic education were more effective and led to support for environmentally friendly food, where, as mentioned above, consumer health could also be an important factor. Another environment-related statement (“you would be willing to give up a favorite product if you knew that it was not environmentally friendly”) was more radical because it created a situation where the individual needed to give up a product. Regardless of the characteristics of a group of respondents, support for this statement decreased, and there were no differences in characteristics between the groups, indicating that the place of residence, education, number of children and income did not affect support for the defined behavior. At the same time, although the support relatively decreased (average = 2.21), the respondents were still in favor of giving up a very favorite product if it made a significant effect on nature. The second part of prosocial statements pertains to patriotism. Regarding the previous dimension, economic statements, it could be observed that there were no significant differences in opinions about the statements related to support for local food, as this made a beneficial effect on the local economy. However, there were differences in opinions about the statement “It is important for you to have as many local ingredients as possible in your food”. First, differences (p-value = 0.029) were observed between buyers with children (average = 2.09), who expressed less support, and those without children, who expressed more support (average = 1.87). The respondents’ places of residence also influenced (p-value = 0.000) support for this statement. Rural residents were more likely to buy local food (average = 1.73) than urban residents (average = 2.03). It was found above that, overall, differences in respondent characteristics did not significantly affect support for the economic statements. However, when it comes to a certain sentiment towards local food, this is the case. The respondents overall supported the statement “A meal made from local products is on better quality than a product made from imported products”, but it was influenced by various social characteristics. Similarly to the previous statement on the role of local food ingredients, this statement was more supported by respondents without children (average = 1.76) than those with children (average = 2.04), with significant differences (p-value = 0.000). Differences in the respondents’ support by level of education were also significant (p-value = 0.000). The respondents with a lower level of education valued local food higher (average = 1.55) than those with a higher level of education (average = 2.05). Based on the previous finding that the level of education affects incomes, it could be expected that support for local food is also relatively higher among respondents with lower incomes. Indeed, buyers with an income below EUR 300 per household member expressed higher support (average = 1.68), while those with a high income (above EUR 800 per household member) were less convincing (average = 2.12). Of course, rural residents (average = 1.66) had higher confidence in the overall quality of local food than urban residents (average = 1.98). It is therefore not surprising that rural residents were more active in buying directly from local food producers. Stronger support for the statement “I try to buy products directly from the local producers (at markets, direct sales, on the farm etc.)” was expressed by rural residents (average = 1.87) than by urban (average = 2.27) residents. The level of support also differed depending on whether the respondents had or did not have children—the support of those without children was higher (average = 2.07) than that of those with one child (average = 2.31). Other characteristics, such as education or an income level, did not make a significant effect on the opinions, and there was overall support for the statement. Overall, there was strong support for the statement “People need to be more educated about the origin, quality and production of local products”, which was observed across all of the social groups of the respondents (average = 1.68). The only characteristic that contributed to a difference in opinions was the level of education (p-value = 0.034). The respondents with secondary education (average = 1.54) expressed higher support than those with higher education (average = 1.69).

An analysis of the differences in support expressed by the segment mentioned in the hypothesis—a family living in the city with children and higher education—for the pro-social statements reveals that their overall support for local and environmentally friendly food was lower than that expressed by other respondents (Table 6).

Table 6.

Opinions on prosocial values among respondents with special characteristics.

The consumers of this segment showed less support for all of the statements. They were most likely to buy food directly from the producer, as it was not very important for this segment (average = 2.46) compared with the other segments (1.90). This segment also tended to agree that food should be organic (average = 2.02). Additionally, the households would prefer local products (2.11) and would certainly like more information on the origin, production and quality of local food (average = 1.81) but were not convinced to give up their favorite products if they were aware of the negative impacts on the environment (average = 2.44).

5. Discussion

This study analyzed the consumer values that are important when choosing foods, especially artisanal foods. On the one hand, it could be found that the results were surprising, as households with high incomes (more choices of food), children (higher responsibility for the environment and the local community where their offspring live and higher food quality requirements, the function of raising children/being role models), higher education (broader worldviews, as most of the curricula include social disciplines) and better access to diverse information (less of a language barrier) and living in a city are more open to prosocial values. However, the present research did not prove this; on the contrary, the respondents who had this characteristic, although they mostly appreciated such values, expressed less support than the other respondents did. On the other hand, the results were not surprising because it is premature to assume that if the social status of the population changes, their awareness and desire to get involved in the realization of prosocial values also change. This is consistent with the results of research on the environmental Kuznets curve, which predicts that the environmental impact will increase and then decrease as the economy develops. Unfortunately, this is largely not the case [47,48] but rather a policy trajectory that should be considered by policy makers as a potential trajectory. It is important that the bell-shaped curve was used to describe the development process in the present research (Figure 1). It was analyzed from the microeconomic perspective as prospects for the industry in the segmentation of different local foods, finding their place in the market for very simple products such as unprocessed food and in very specific (niche) markets. At the same time, the course of development shown in Figure 1 could be assessed from a deliberate purchase perspective. E-commerce speeds up the development of global food chains [49]; on the other hand, the opposition emerged in the form of a slow food movement, locavorism and conscious consumption, which basically emphasizes the realization of different kinds of values that overwhelm primary hedonic instincts. It is possible that the role of a smart lifestyle course is minimal, which allows consumers to assess their choices of sustainable food [50]. It is very possible that in the case of Latvia too, the segment examined is plagued by hedonic complacency and nostalgic feelings for foreign travel destinations related to rest and relaxation. Consumption, like that of any member of society, is determined by the process of making sense. Sense-making is a central factor of human behavior because it is the primary site where meanings that inform and constrain identity and action materialize [51]. Government institutions and local authorities should play an active role in shaping prosocial behavior by creating an appropriate information base for meaning. This can bring benefits to both consumers and society as a whole [52]. Social media should also take some responsibility, mainly for hedonic personal advice on food consumption [53]. Artisan food producers need to think about how to complement their product with services that are associated with positive emotions for the consumer, because, in addition to information, personal experience plays an important role in making sense [54]. Both the economic and prosocial values of local food are mainly emphasized by the rural population with a lower level of education, which could indirectly indicate the protection of their traditional way of life, less choices (travel), more personal involvement in producing food in their community and a greater awareness of the environment, as many of those in the rural population are directly involved in agricultural production that is subject to government intervention. However, these are just assumptions that need to be further researched. The present research has also showed that there is a strong public demand for additional information and a wider debate on the role of local food, which is likely to change consumer behavior towards prosocial values in the long term.

6. Final Remarks

Consumer behaviour is influenced by their accepted values. Motives for accepting values are different, both altruistic and the desire to be trendy and fit into a certain society.

The importance of local food in the overall food system has flowed into the unprocessed food and prosocial value food segments. In these segments, demand is inelastic, creating a relative advantage of local food in competition with global food products. It is in these food segments (unprocessed, locally specific and prosocial foods) that consumers see the benefits of local food and are ready to consume it.

The choice of a consumer is influenced not only by personal (genetic, psychological, selfish) motives but also by the concern for children, as well as the children’s own opinions. Children are increasingly influenced not only by their consumption habits but also by the formation of family values (for example, about climate- and environment-friendly behaviour).

Awareness or the ability to not follow habits or very easy-to-understand irritants (low price, product popularity) play an important role in decision-making. At least at the beginning of a behavioural change, additional efforts are needed to analyze the information, although in some cases the consumer may also deliberately choose not to be aware of unpleasant information about the health or environmental effects of his consumption.

In general, Latvian consumers want the desire to support local traditions, the region’s economy and the preservation of the environment to be realized in the products they consume. At the same time, the support is reduced if the consumer has to give up something in favour of these values.

Households living in cities which have children, high incomes and higher education rate the prosocial values of food consumption as significant, while support is lower than for other consumer groups.

This study suggests further research. One possibility is an SEM-PLS (Structural Equation Modelling, Partial Least Square) [55] to unveil the hidden relationships among variables. Other future lines of research could be related to the analysis of consumer recommendations for the development of the local food system included in the survey (which was not reflected in this study).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N.-L.; methodology, K.N.-L.; software, L.J.; validation, K.N.-L., and L.P. (Liga Paulaand); formal analysis, D.K. and L.P. (Liga Paulaand); investigation, L.P. (Liga Paulaand) and L.P. (Liga Proskina); resources, K.N.-L. and L.P. (Liga Paulaand); data curation, L.J. and L.P. (Liga Paulaand); writing—original draft preparation, K.N.-L.; writing—review and editing, K.N.-L., L.P. (Liga Paulaand) and L.J.; visualization, K.N.-L.; supervision, K.N.-L.; project administration, L.P. (Liga Paulaand); funding acquisition, L.P. (Liga Proskina). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Latvian Council of Science, project “Resilient and sustainable rural communities: the multiplier effect of the local food system”, project No. LZP-2020/2-0409.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Group of Chief Scientific Advisors. Towards a Sustainable Food System: Moving from Food as a Commodity to Food as More of a Common Good: Independent Expert Report; European Commission Publications Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament. The Council Of The European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on Support for Rural Development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005; The Council Of The European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ruben, R.; Verhagen, J.; Plaisier, C. The Challenge of Food Systems Research: What Difference Does It Make? Sustainability 2019, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Béné, C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security—A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Sec. 2020, 12, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, S. The impact of COVID-19 related ‘stay-at-home’ restrictions on food prices in Europe: Findings from a preliminary analysis. Food Sec. 2020, 12, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naglis-Liepa, K.; Proskina, L.; Paula, L.; Kaufmane, D. Modelling the multiplier effect of a local food system. Agron. Res. 2021, 19, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Machado Vial, L.A.; Viegas, C.V. Critical success factors in Short Food Supply Chains: Case studies with milk and dairy producers from Italy and Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival Carter, E.; Welcomer, S. Designing and Distinguishing Meaningful Artisan Food Experiences. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Villarreal, H.H.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.P.; Izquierdo-Yusta, A.; Gómez-Cantó, C.M. Food Values, Benefits and Their Influence on Attitudes and Purchase Intention: Evidence Obtained at Fast-Food Hamburger Restaurants. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro-Rodríguez, A.I.; Pérez-Jiménez, I.R.; Esteban-Dorado, A.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.P. Food Values, Satisfaction, and Loyalty: Some Evidence in Grocery Retailing Acquired during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, A.; Laganà, V.R.; Laven, D.; Marcianò, C.; Skoglund, W. Consumer Habits of Local Food: Perspectives from Northern Sweden. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism; Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1991; p. 1. Available online: https://cedar.wwu.edu/hcop_facpubs/1 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumah, M.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Novo, P.; Pippa, J.; Chapman, J. Revisiting the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behavior to Inform Land Management Policy: A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Model Application. Land 2020, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.E.; Tirotto, F.A.; Pagliaro, S.; Fornara, F. Two Sides of the Same Coin: Environmental and Health Concern Pathways Toward Meat Consumption. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkoris, M.D.; Stavrova, O. Meaning of food and consumer eating behaviors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 9, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luomala, H.; Puska, P.; Lähdesmäki, S.M.; Kurki, S. Get some respect—Buy organic foods! When everyday consumer choices serve as prosocial status signaling. Appetite 2020, 145, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskine, K.J. Wholesome Foods and Wholesome Morals? Organic Foods Reduce Prosocial Behavior and Harshen Moral Judgments. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nipers, A.; Pilvere, I. Assessment aof Value Added Tax Reduction Possibilities for Selected Food Groups in Latvia. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Rural Development, Kaunas, Lithuania, 23–24 November 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oliver, R. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Swan, J.E. Equity and disconfirmation perceptions as influences on Merchant and product satisfaction. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W.; Sullivan, M.W. The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglīte, A.; Kaufmane, D. Bread-Baking Traditions Incorporated in a Rural Tourism Product in Latvia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Food and Agricultural Economics, Alanya, Turkey, 25–26 April 2019; pp. 154–161. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20193521454 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gowdy, J.; Seidl, I. Economic man and selfish genes: The implications of group selection for economic valuation and policy. J. Soc. Econ. 2004, 33, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhathoki, M.; Zølner, A.; Nielsen, T.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Reinbach, H.C. Intention to buy organic fish among Danish consumers: Application of the segmentation approach and the theory of planned behaviour. Aquaculture 2022, 549, 737798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martensen, A.; Lars Grønholdt, L. Children’s influence on family decision making. Innov. Mark. 2008, 4, 14–22. Available online: https://www.businessperspectives.org/images/pdf/applications/publishing/templates/article/assets/2404/im_en_2008_04_Martensen.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bertol, K.E.; Broilo, P.L.; Espartel, L.B.; Basso, K. Young children’s influence on family consumer behavior. Qual. Mark. Res. 2017, 20, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmaa, A.; Sonwaneyb, V. Theoretical modeling of influence of children on family purchase decision making. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 133, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahneman, D. Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 1449–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, S.; Subramaniam, B. Exploring Socio-Cognitive Mindfulness in the Context of Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gisslevik, E. Education for Sustainable Food Consumption in Home and Consumer Studies. 2018. Available online: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/54558/1/gupea_2077_54558_1.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- The European Parliament. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of The European Parliament and of The Council on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers, amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004; The Council Of The European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C.R. Viewpoint: Are food labels good? Food Policy 2021, 99, 101984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D.K. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development. Regions of Latvia. Available online: https://www.varam.gov.lv/lv/planosanas-regioni (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Official Statistics Portal. Offiscial Statistics of Latvia. Available online: https://data.stat.gov.lv/pxweb/en/OSP_PUB/START__POP__IR__IRE/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Dahs, A.; Berzins, A.; Krumins, J. Challenges of Depopulation in Latvia’s Rural Areas. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference. Econ. Sci. Rural. Dev. 2021, 55, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvijas Lauku Forums. (Latvian Rural Forum). Jaunienācēji—Lauku Telpas Revitalizācijai. (Newcomers—Potential for Rural Revitalization). 2022. Available online: https://saite.lv/iAojh (accessed on 10 January 2022). (In Latvian).

- LR Ministry of Agriculture. Informative Report. Latvian Bioeconomy Strategy 2030. Available online: https://www.zm.gov.lv/public/files/CMS_Static_Page_Doc/00/00/01/46/58/E2758-LatvianBioeconomyStrategy2030.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bite, D.; Kruzmetra, Z. Review on the Consumers’ Response to the COVID-19 Crisis in Latvia. Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference. Econ. Sci. Rural. Dev. 2021, 55, 526–534. [Google Scholar]

- Novada Garša. Catalog of Home Producers and Food Artisans. Available online: https://www.novadagarsa.lv/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Zeverte-Rivza, S.; Gudele, I. Digitalisation in times of COVID-19—The behavioural shifts in enterprises and individuals in sector of bioeconomy. Econ. Sci. Rural. Dev. 2021, 55, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, J.; Del Cura-González, M.I.; Gómez-Gascón, T.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Domínguez-Bidagor, J.; Beamud-Lagos, M.; Pérez-Rivas, F.J. Differences between willingness to pay and willingness to accept for visits by a family physician: A contingent valuation study. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Loss Aversion in Riskless Choise: Reference-Dependent Model. Q. J. Econ. 1991, 106, 1039–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, E.M.; Colantoni, A.; Gambella, F.; Cudlinová, E.; Salvati, L.; Rodrigo-Comino, J. Revisiting the Environmental Kuznets Curve: The Spatial Interaction between Economy and Territory. Economies 2020, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglis-Liepa, K. The environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis as theoretical approach in renewable energy promotion in Latvia. Manag. Theory Stud. Rural. Bus. Infrastruct. Dev. 2011, 27, 140–147. Available online: http://mts.asu.lt/mtsrbid/article/view/282 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Gharehgozli, A.; Iakovou, E.; Chang, Y.; Swaney, R. Trends in global E-food supply chain and implications for transport: Literature review and research directions. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2017, 25, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.B.; Simons, J. Good Attitudes Are Not Good Enough: An Ethnographical Approach to Investigate Attitude-Behavior Inconsistencies in Sustainable Choice. Foods 2021, 10, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Obstfeld, D. Organizing and the Process of Sensemaking. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wood, G.; Day, R.; Creamer, E.; van der Horst, D.; Hussain, A.; Liu, S.; Shukla, A.; Iweka, O.; Gaterell, M.; Petridis, P.; et al. Sensors, sense-making and sensitivities: UK household experiences with a feedback display on energy consumption and indoor environmental conditions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 55, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orste, L.; Krumina, A.; Kilis, E.; Adamsone-Fiskovica, A.; Grivins, M. Individual responsibilities, collective issues: The framing of dietary practices in Latvian media. Appetite 2021, 164, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chater, N.; Loewenstein, G. The under-appreciated drive for sense-making. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2016, 126, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sellitto, M.A.; Hermann, F.F. Influence of Green Practices on Organizational Competitiveness: A Study of the Electrical and Electronics Industry. Eng. Manag. J. 2019, 31, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).