Abstract

Even though tourists increasingly value sustainable practices in tourism businesses and destinations, price is still one of the main determinant factors in their decisions. Therefore, for destination managers it is essential to understand tourists’ willingness to pay an additional price to visit a place where sustainable practices are adopted. In this context, and building on social psychology theories, the present study proposes and tests a causal model encompassing tourists’ Willingness To Pay (WTP) for sustainability in tourist destinations as well as their own sustainability attitudes, namely: Environmental Beliefs, Ecotour Attitudes, and Sustainable Consumption Behaviour. To this end, data were collected through a questionnaire survey of Portuguese tourists (n = 567). The hypothesised relationships between the latent variables were then tested using Structural Equations Modelling (SEM) procedures. The results show that Environmental Beliefs significantly affected both Ecotour Attitudes and Sustainable Consumption Behaviour, and that the latter two significantly affected WTP. However, no significant effect of Environmental Beliefs on WTP was found. These findings provide useful insights for destination managers aiming to more effectively cater to sustainability-oriented tourists. Future research should attempt to assess the role of other determinants of WTP.

1. Introduction

The topic of sustainability and the demand for sustainable products and services is not new. International institutions such as the United Nations and the International Panel on Climate Change agree that there is a need for stronger efforts to protect the global environment. Naturally, tourism does not stray from this trend and sustainable tourism is one of the key agenda points for Global Sustainable Development 2030. Tourism is expected to provide a great contribution towards the global sustainable development scenario. Beginning in the 1980s as a reaction to the realisation of the impacts caused by mass tourism many new forms of more responsible travel have been conceptualised, including community-based tourism, fair-trade tourism, and pro-poor tourism [1]. Amongst these the term that has received the most traction is ecotourism, defined by The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) [2] as a type of nature-based tourism where visitors have a “responsible attitude to protect the integrity of the ecosystem and enhance the well-being of the local community” (p. 32). Because such responsible attitudes should not be restricted to nature-based travels, the more comprehensive term “sustainable tourism” has become prevalent in discussions of the role of tourism in fostering sustainable development. The UNWTO [3] defines sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities” (p. 17). If planned and managed in keeping with such a definition, as Dolnicar [4] observes, tourism can play an effective role in achieving economic and social development while preserving natural and cultural resources.

Authorities worldwide are committed to making stronger efforts to meet carbon emission reduction targets and look after the planet’s health. Concerns regarding sustainability, however, are not exclusive to authorities. Consumers are increasingly aware of the impacts that economic activities have on the environment and seek to play their part in achieving sustainability goals. Likewise, tourists include environmental and sociocultural sustainability criteria in their destination choice process. Consequently, businesses embrace sustainable practices as part of their value propositions, aiming to gain competitive advantages. Nonetheless, carrying out these practices tends to increase operational costs and consequently makes services more expensive. In this context, before deciding to implement such practices from a managerial perspective, destination and tourism business managers need to know whether there are enough consumers willing to pay a premium price for them. Consequently, in addition to understanding which sustainable practices are valued the most by tourists it is crucial to know how much of a premium price they are willing to pay in order to visit destinations and use services where these practices are carried out. In other words, it is important to understand tourists’ willingness to pay for sustainability in tourist destinations.

Most studies addressing tourists’ willingness to pay a premium price for sustainability have examined the issue in the context of tourism services such as hotels [5] and air travel [6]. Studies addressing this concept on the destination level often focus on contexts such as ecotourism and visits to protected areas. Therefore, they point to context-specific factors such as awareness of being in a protected aera and the number of animal species sighted [7] in the context of visits to natural areas, climate change-related risk perceptions and place meanings in the context of nature-based tourism [8], and attitudes towards environmental protection in the context of paying fees to enter protected areas [9].

The addressed contributions show that the concept of WTP for sustainability in tourist destinations is of particular relevance to industry stakeholders, who are committed to accomplishing efforts to protect the global environment. Furthermore, they show that tourist behaviour is affected by attitudes and values regarding sustainability issues. However, although previous studies have addressed the way in which tourists’ sustainability attitudes affect their willingness to pay for sustainability in specific contexts, to the best of our knowledge no study has yet empirically tested a general causal model of tourists’ WTP which assesses the role of individual sustainability attitudes rather than context-related variables. In this context, the present investigation aimed to propose and test a causal model encompassing tourists’ willingness to pay for sustainability in tourist destinations and their related sustainability attitudes, namely, Environmental Beliefs, Ecotour Attitudes, and Sustainable Consumption Behaviour.

To accomplish this purpose, data were collected through a questionnaire survey of Portuguese tourists (n = 567). The model’s latent variables were subsequently operationalised in a causal model which was then tested through Structural Equations Modelling (SEM) procedures. The results show that environmental beliefs significantly affect both ecotour attitudes and sustainable consumption behaviour. Accordingly, both ecotour attitudes and sustainable consumption behaviour significantly affect tourists’ WTP. On the other hand, a direct effect of environmental beliefs on WTP was not verified. These findings provide useful insights for destination managers aiming to more effectively target sustainability-oriented tourists with their marketing strategies. Finally, despite the verified significant relationships WTP cannot be sufficiently predicted by the other latent variables, which leaves a fertile avenue for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism and Sustainability

Although there is no universally accepted scale for measuring sustainability in different tourism scenarios, previous authors have made significant progress towards providing effective alternatives. Asmelash and Kumar [10], for instance, developed and validated a list of sustainability indicators for tourism destinations based on the perceptions of residents, tourists, and local stakeholders. Their indicators are grouped in four dimensions, Economic Sustainability, Socio-cultural Sustainability, Environmental Sustainability, and Institutional Sustainability, with each dimension correlated with the other three. Such a model effectively expands the triple bottom line principle of sustainability (environmental, sociocultural, and economic) in tourism destinations. While the sustainability of destinations must take into account these four dimensions, Li, Kim, and Lee [11] argue that tourism development should be planned and operated with the goal of securing long-term benefits for all actors involved, with special consideration of how the local community is involved in the overall development process.

The local community has received significant attention from scholars addressing tourism sustainability. In a systematic review of sustainable tourism indicators carried out by Rasoolimanesh et al. [12], of the 97 papers addressed only a few mentioned tourists as stakeholders. The local community, on the other hand, was mentioned in 46% of the studies analysed. The authors suggest that future studies must consider both tourists’ experience in destinations as well as their relationship with the Sustainable Tourism Indicators based on, amongst other criteria, their relevance to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Despite the holistic view on tourism sustainability demonstrated by some authors, it should be noted that most studies on this subject focus on environmental sustainability. In this context, common themes include environmental sustainability in nature-based tourism [13], the potential contribution of environmental sustainability to tourism growth [14], and the possibility of co-existence between luxury and environmental sustainability [15]. Economic sustainability, in turn, is pursued by any business or development plan regardless of whether they adopt an overt sustainability orientation. Studies focused on this dimension often aim to verify whether a certain local tourism industry [16], product [17], or business model [18] is indeed economically sustainable. As it has only been added to the tourism sustainability dimensions by the aforementioned study of Asmelash and Kumar [10], institutional sustainability is not addressed specifically in previous studies. However, it is arguably pursued by any business, especially destinations, as the literature on tourism planning and development (e.g., [19]) point to political will and the collaboration of all actors involved as essential for making tourism development and sustainability viable.

As concerns socio-cultural sustainability, due to its complexity authors tend to focus on specific concepts such as identity preservation [20], tangible and intangible heritage, cultural heritage [21], cultural vitality, cultural diversity, economic viability, locality, eco-cultural resilience, eco-cultural civilization [22], and social capital [23]. Regarding the specific aspects that contribute to sociocultural sustainability in tourism destinations, Getzner’s [24] findings highlight socio-economic variables and the availability of cultural infrastructure as well as municipal cultural spending. These contributions are important for understanding how tourism authorities pursue sustainability goals in tourism development.

Despite the importance of these principles, as observed by Font and McCabe [25] in order to be truly sustainable destinations and services need the support of consumers, who must be convinced to choose responsible products rather than their non-responsible counterparts. Consequently, no analysis of destinations’ sustainability would be complete without taking into account the demand side, i.e., the predisposition of tourists to choose sustainable tourism destinations and to engage in sustainable behaviour at the destination. Corroborating the relevance of considering both triple bottom line principles and consumer likeliness to choose sustainable products and destinations, an integrative review carried out by Nadalipour and Khoshkhoo [26] shows that many authors agree that one cannot address destinations’ sustainability and competitiveness without considering the economic, sociocultural, and ecological dimensions as well as all the stakeholders involved in the tourist activity, which naturally includes consumers. In this context, studies on tourism sustainability often adopt one of two distinct approaches, a supply-side approach or a demand-side approach [27]. Amongst those, demand-side studies are of particular relevance to the research problem addressed by the present study, and are therefore addressed in greater detail here.

Many studies on tourism sustainability have analysed the demand for tourism services. Generally, these show that tourists who value sustainable practices are more inclined to choose services, especially hotels, that employ such practices over those that do not [28,29,30,31,32]. Accordingly, Lee, Hsu, Han, and Kim [33] show that the overall image of green hotels is positively related to the behavioural intentions of consumers. Several demand-side studies on the sustainability of tourism services have explored the extent to which tourists are willing to make sacrifices to have ensure a more sustainable travel experience. Chia-Jung and Pei-Chun [34], for instance, conclude that although hotel customers generally prefer luxury rooms and value the provision of toiletries, many are willing to sacrifice service quality for the sake of sustainability performance. Accordingly, Brau [35] showed that tourists in Sardinia, Italy are willing to sacrifice closeness to the beach in order to decrease their impact on the natural environment.

Studies on the market effectiveness of sustainable practices in tourism destinations, on the other hand, are much less abundant. Nevertheless, several studies do provide valuable contributions, empirically corroborating the link between the sustainability of tourist destinations and their competitiveness. This is the case for Khalifa [36] and Cucculelli and Goffi [37], who demonstrate using empirical data in two very distinct destinations (Egypt and a set of small destinations in Italy, respectively) that sustainability variables significantly impact destination competitiveness. Additionally, López-Sánchez and Pulido-Fernández [38] conclude that market segmentation is useful for planning and managing demand-oriented policies. In sum, demand side studies on tourism sustainability provide useful insights into what tourists value the most when choosing a sustainable destination. Questions remain, however, regarding who those tourists are and how to effectively promote a destination to them, which is where the study of tourist behaviours and attitudes enters the picture.

2.2. Tourists’ Sustainable Behaviours and Attitudes

Social psychology theories explain that behaviour is influenced by attitudes, among other factors [39]. These theories have been employed to facilitate the comprehension of consumer behaviour in various scenarios. In the context of sustainability, Kim, Hall, and Han [40] address behavioural influences on support for crowdfunding initiatives related to SDGs, concluding that the strongest effects are exerted by agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness. Addressing behavioural variables and SDGs in the context of travellers’ biosecurity behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic, Kim, Bonn, and Hall [41] show that prosocial behaviour and perception have significant impacts on intervention and influence resilience and tourists’ biosecurity behaviour. In the context of tourism sustainability, many studies corroborate the association between attitudes and behaviour [42,43]. For instance, Mohaidin, Wei, and Murshid [44] conclude that environmental attitudes are positively correlated with the intention to select sustainable tourist destinations, as well as with tourists’ intentions to engage in environmentally responsible behaviour.

Several studies suggest that tourists’ environmental attitudes are directly related to the type of destination they visit and the type of activities they carry out in those destinations. In this context, studies [42,45,46] have shown that the degree of environmental commitment of tourists visiting a natural park is much higher than that of those visiting beaches. Other studies have shown that tourists who usually engage in outdoor activities (e.g., hiking or diving) have an increased tendency to emphasize the environmental aspects of traveling [47,48,49]. Accordingly, authors such as Eagles and Higgins [50] and Luo and Deng [51] provide evidence that travellers who exhibit positive environmental attitudes tend to portray a stronger desire to experience actives in nature.

Not all tourists who engage in nature-based activities seek similar experiences or have similar attitudes, however. This is evidenced by Lee, Jan, Tseng, and Lin [52], who segmented visitors to Taiwan’s Liuqiu Island into four different groups, multi-experience recreationists, aestheticists, hedonists, and knowledge seekers, based on their recreation experiences. Accordingly, tourists who engage in nature-based tourism activities are not equally environmentally committed. For instance, Weaver and Lawton [53] concluded that “harder ecotourists” show higher levels of environmental commitment and affinity with wilderness-type experiences, while “softer ecotourists” are much less committed to either dimension. The same study shows that although “structured ecotourists” have a high level of commitment, their consumption patterns are analogous to those of mass tourists. Findings such as these evidence that (as observed by Budeanu [54]) despite tourists’ general trend to state high levels of environmental commitment, only a few behave accordingly, that is, buy responsible tourism products, choose environmentally friendly transportation, and act responsibly towards local communities.

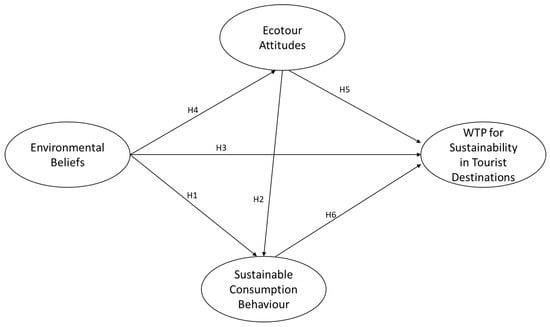

Despite these findings suggesting that tourists’ actions are not always accurately predicted by their attitudes, various studies show that some degree of relationships is indeed verified. Grilli et al. [55], for instance, demonstrate that environmental beliefs influence individual tastes. Their study also highlights the importance of ecotourism attitudes and pro-environmental private behaviour. This is in line with previous findings by Dolnicar [4], according to whom environmentally responsible behaviour at the destination is influenced by environmental attitudes, place attachment, level of commitment to the environment, means of transportation, environmental knowledge and education, and environmental behaviour at home. Considering these findings, we propose the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Environmental beliefs positively affect sustainable consumption behaviour.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Ecotour attitudes positively affect sustainable consumption behaviour.

Various studies [56,57,58,59] have concluded that sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, and education level as well as personal values, attitudes, motivation, knowledge, ability, and opportunity to engage in sustainability practices play an important role in determining customers’ willingness to pay more for environmentally friendly tourism products. This last construct, willingness to pay for a more sustainable destination, is considered to play an important role in destinations’ quest to be competitive as a means of becoming more sustainable. After all, if sustainable destinations need to convince consumers to choose their sustainable products (which often implies paying a premium price) it is important to know whether consumers are willing to pay more to visit a destination where certain sustainable practices are carried out. Studies on the topic have mostly addressed tourists’ willingness to pay in the context of tourism services such as hotels or specific types of tourism products or experiences such as ecotourism or visits to protected areas. As Agag, Brown, Hassanein, and Shaalan [60] demonstrate, no single factor is sufficient to decode travellers’ willingness to pay more for sustainability. Therefore, each study further contributes to achieving an understanding of the construct’s determinants in each specific context. In the context of green products and services offered by hotels, for instance, Galati et al. [5] have shown that electronic word of mouth (e-WOM), physical image, consumer income, and green attributes related to transportation services all have a positive effect on customers’ willingness to pay. In the context of air travel, Seetarama, Songb, Ye, and Yec [6] found that UK tourists are willing to pay a higher Air Passenger Duty for business class and long-haul trips.

In the context of visits to natural reserves, Surendran and Sekar [7] showed that tourists’ level of education and the number of animal species sighted both positively affected willingness to pay. In the context of protected areas, Wang and Jia [61] concluded that income level and the awareness of being in a protected area were the most significant predictors of tourists’ willingness to pay. Income level was a significant factor in the more specific context of marine parks [62]. Addressing WTP in nature-based tourism, McCreary et al. [8] found that climate change-related risk perceptions as well as place meanings and tourist age and income all had a positive effect. In the context of ecotourism, Meleddu and Pulina [58] showed that visitors with a high awareness of ecotourism were more willing to support projects, and that subjective norms and environmental beliefs both had a positive effect on willingness to pay. In the specific scenario of willingness to pay an entrance fee to natural attractions, Reynisdottir, Song and Agrusa [9] found that such a construct is influenced by visitors’ attitudes towards environmental protection as well as demographic and contextual variables such as their number of previous visits and history of paying entrance fees. Finally, in a study not restricted to any specific tourism product Hedlund [63] found a positive effect of environmental concern on both willingness to accept economic sacrifices to protect the environment and intention to purchase ecologically sustainable tourism alternatives.

Considering these findings,

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Environmental beliefs positively affect WTP.

Hultman, Kazeminia, and Ghasemi [57] conclude that while environmental beliefs are positively related to willingness to pay, this effect is indirect as it is mediated by ecotourism attitudes, and even this path is externally mediated by motivation to travel. Therefore:

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Environmental beliefs positively affect ecotour attitudes.

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Ecotour attitudes positively affect WTP.

Finally, In the context of hotels, Chia-Jung and Pei-Chun [34] have shown that customers with high levels of “green consumption” are more likely to choose hotels that adopt more sustainable practices. Accordingly, in the context of destinations, Araújo, Marques, Candeias, and Vieira [64] found that young travellers present higher levels of general sustainable consumption behaviour and are more willing to pay for sustainable practices in tourist destinations. Considering these contributions along with those on behavioural theories and sustainable tourists’ choices:

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Sustainable consumption behaviour positively affects WTP.

The research hypotheses proposed in the present study are graphically represented in Figure 1, which illustrates the proposed model.

Figure 1.

The proposed model.

An important methodological contribution to the assessment of willingness to pay is provided by Aydın and Alvarez [65], who proposed and validated a list of items related to destination sustainability and willingness to pay for a sustainable destination using a mixed method approach. The authors conclude that cultural tourists are more willing to pay for cultural and environmental protection practices, namely, preservation of historical and cultural resources, protection of green areas, fauna and flora, and protection of the overall architectural character of the location surrounding the cultural destination.

Although the topic of willingness to pay for a sustainable destination and tourists’ sustainability attitudes have been addressed previously, the relationship between them has only been examined in specific contexts such as ecotourism, nature-based tourism, and visits to natural areas. Considering the addressed contributions and knowledge gaps, the present study aims to contribute to the literature on tourism destination sustainability by modelling willingness to pay for a more sustainable destination and tourists’ sustainability attitudes within a causal model.

3. Materials and Methods

The present paper aimed to propose and test a causal model encompassing tourists’ willingness to pay for sustainability in tourist destinations as well as their sustainability attitudes. To this end, the context of Portuguese tourists traveling both domestically and internationally was adopted as the research setting. The data collection instrument consisted of a survey questionnaire, which was developed based on contributions from previous studies. Regarding the WTP construct, the list of items proposed and validated by Aydın and Alvarez [65] to understand Turkish cultural tourists’ willingness to pay for a more sustainable destination was adapted to the present study’s setting. The aforementioned authors proposed a list of sustainability items through a thorough qualitative analysis of TripAdvisor cultural destination reviews. Additionally, through a quantitative survey they reduced the list of items to a smaller list of factors and subsequently confirmed their dimensionality, effectively validating scales for items measuring tourists’ evaluation of sustainability criteria and their willingness to pay in cultural destinations. Therefore, this list of items was deemed adequate as a starting point for the present investigation.

As in the present study, the aim of Aydın and Alvarez was to assess how sustainability attitudes affect willingness to pay in general, rather than in each of its dimensions; the list was used as a measure of the whole construct, which is adequate for this study’s setting and sample. This decision was corroborated by measurement model assessment procedures, which indicated that the list is reliable (Chronbach’s alpha = 0.972), unidimensional, and convergently valid (all items load significantly). These tests were carried out following the addition of three new items to the original list, which aimed to increase its adequateness to the present research setting. Therefore, they the new items’ fit to the measure is corroborated as well.

The list of sustainability attitudes was in turn adapted from a study by Grilli et al. [55] on prospective tourist preferences for sustainable tourism development in Small Island Developing States (SDIS). The study employed three types of environmental attitudes or behaviours: environmental beliefs, ecotour attitudes, and pro-environmental private behaviour, of which only the latter was not used in the present study. Instead, Sustainable Consumption Behaviour as proposed by Araújo et al. [64] was adopted. This decision relied on the cited work’s conclusion that the pro-environmental private behaviour items employed by Grilli et al. [55] do not apply well to Portuguese customs, which is corroborated by the construct’s lack of reliability (reliability tests would successively suggest the exclusion of one or more factors). Chronbach’s alpha values corroborate the reliability of Environmental Beliefs (0.931), Ecotour attitudes (0.887), and Sustainable Consumption Behaviour (0.948). However, one item from Ecotourism attitudes (“visiting sustainably managed tourist areas should be subject to a higher relative payment”) was excluded due to its negative impact on reliability and subsequent low loading within the structural model.

The wording of items was adapted to reflect the broader context of the present investigation in terms of destination types (i.e., not limited to cultural destinations). Wording adaptation aimed to tailor the items’ semantic meaning to Portuguese inquiries. To this end, a panel with experts (Portuguese tourism researchers) was consulted.

In line with the research settings, the survey was carried out exclusively in Portuguese. The items were then translated back to English for the purpose of reporting the results. The questionnaire was applied online through Google Forms to a convenience sample of Portuguese people who had travelled within the last twelve months. The data collection procedures took place during the months of April and May 2021, during which Portugal, like most European countries, was experiencing severe travel restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, although travel was allowed within certain limitations. The questionnaire was disseminated in travel-related social media groups as well as on marketing survey platforms. Respondents’ knowledge of sustainability or sustainable tourism was not assessed, as the goal was to measure travellers’ sustainability attitudes and willingness to pay more for a set of sustainable practices in tourism destinations regardless of their theoretical knowledge of the subject. In line with this goal, none of the groups where the questionnaire was disseminated explicitly mentioned sustainability as a topic of interest. A total of 567 valid responses were collected. Table 1 summarises the sample’s sociodemographic and travel behaviour profile.

Table 1.

Sample characterisation.

4. Results

To assess a causal model encompassing tourists’ willingness to pay for sustainability in tourist destinations and their sustainability attitudes, Structural Equations Modelling (SEM) was employed. Before proceeding to the structural model test, the constructs’ dimensionality, convergent validity, reliability, and discriminant validity were tested using a measurement model assessment on AMOS (Version 25) software. In this context, the procedure served to verify whether the adopted scales were indeed adequate to measure their respective constructs within the settings of the present investigation. This was deemed necessary as the studies in which those scales were developed have quite different settings, namely, UK tourists travelling to Small Island Developing States (SDIS) [55] and domestic Turkish cultural tourists [65], respectively. The following section addresses the measurement model assessment.

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

As shown in Table 2, the model fit is acceptable, although not exceptional, as all goodness-of-fit indicators either exceed the recommended cut-offs [66] or are in their close vicinity. There are a few reasons for the model fit being less than ideal. First, the sample size is quite high, and the chi-square goodness-of-fit test tends to reject model-to-fit data as the sample size increases [67]. Considering this, and as suggested by several authors [67,68], other fit measures are reported. Among these the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) is probably held back by the model’s lack of parsimony, which is a result of having a latent variable composed of many items (16 items for WTP for Sustainability in Tourist Destinations). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI), however, does exceed the mentioned threshold (0.9). Accordingly, the Root Means Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is within the recommended values (0.05 to 0.08). This suggests that the constructs are indeed unidimensional.

Table 2.

Summary of Structural Equations Modelling results.

As shown in Table 3 and Table 4, all of the items for WTP, Ecotour Attitudes, Environmental Beliefs, and Sustainable Consumption Behaviour load strongly and significantly to their respective constructs. All loadings greatly exceed 0.5, which suggests that the constructs have convergent validity; this is reinforced by the generally good model fit. Regarding reliability, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3 the Cronbach’s Alpha values of all constructs are above Nunnally’s [69] 0.7 threshold. Moreover, the Composite Reliability (CR) values are all higher than the 0.60 cut-off proposed by Bagozzi and Yi [70], and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values of all constructs are above 0.5, which according to Fornell and Larcker [71] is sufficient evidence of discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Dimensionality, convergent validity, reliability, and discriminant validity assessment of Willingness to Pay for Sustainability in Tourism Destinations.

Table 4.

Dimensionality, convergent validity, reliability, and discriminant validity assessment of Environmental Beliefs, Ecotour Attitudes, and Sustainable Consumption Behaviour.

4.2. Structural Model Testing

This section describes the procedures for testing the hypothesised relationships between the latent variables within the model, namely, WTP, Environmental Beliefs, Ecotour Attitudes, and Sustainable Consumption Behaviour. As shown in Table 2, concerning the variables hypothetically affecting sustainable consumption behaviour the results show a significant (p < 0.005) and moderate (β = 0.302) effect of environmental beliefs, which supports H1. Ecotour attitudes, in turn, also significantly affect sustainable consumption behaviour (p < 0.005), supporting H2, although the strength of the effect is modest (β = 0.277). Finally, sustainable consumption behaviour presents a moderate Square Multiple Correlation (R2) of 0.303. This indicates that although the two independent variables in this relationship significantly affect it, they do not exhaustively explain its variance. On the other hand, the effect of environmental beliefs on ecotour attitudes is both significant (p < 0.005) and strong (β = 0.809), which supports H4. Accordingly, ecotour attitudes has a high R2, 0.655, which indicates that a satisfactory proportion of its variances are indeed explained by environmental beliefs.

Regarding the main dependent variable that the study aimed to explain, WTP, the results do not demonstrate a significant direct effect of environment beliefs (p > 0.005). Therefore, H3 cannot be supported. However, the effect of ecotour attitudes is indeed significant (p < 0.005), although moderate (β = 0.364), which supports H5. Accordingly, the effect of sustainable consumption behaviour on WTP is significant (p < 0.005), although modest (β = 0.209), which supports H6. In this context, these two variables, ecotour attitudes and sustainable consumption behaviour, mediate the effect of environmental attitudes on WTP. Finally, analogous to sustainable consumption behaviour, WTP presents a moderate R2 (0.328). Once again, this indicates that although the exogenous variables affecting it have a significant effect, they do not satisfactorily explain its variation. A summary of the direct, indirect, and total effects between the latent variables is summarised in Table 5, and a summary of the tested hypotheses is presented in Table 6.

Table 5.

Summary of direct, indirect, and total effects.

Table 6.

Summary of hypotheses testing.

5. Discussion

The present paper aimed to propose and test a causal model encompassing tourists’ willingness to pay for sustainability in tourist destinations and their sustainability attitudes. To this end, a list of WTP for sustainability attributes was adapted from Aydın and Alvarez [65] and the items of environmental beliefs and ecotour attitudes were adapted from Grilli et al. [55]. Moreover, sustainable consumption behaviour as proposed by Araújo et al. [64] was adopted as an additional predictor of WTP. Finally, these latent variables were organised in a causal model which was tested using SEM procedures in AMOS with data collected from a survey with Portuguese tourists (n = 567).

The measurement model assessment shows that the tested list of WTP items is adequate for measuring this construct in the context of the destination choice process of Portuguese tourists as well as in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the data collection procedures took place. Moreover, the constructs of sustainability attitudes, namely, environmental beliefs, ecotour attitudes, and sustainable consumption behaviour, upheld their reliability, dimensionality, and convergent validity within the research settings.

Regarding the hypothesised relationships, the significant effects of environmental beliefs and ecotour attitudes on sustainable consumption behaviour (H1 and H2) are in line with the results of Weaver and Lawton [53], according to which “harder ecotourists” (that is, those with a higher degree of sustainable consumption behaviour within the ecotourism practice) tend to have a high level of environmental commitment.

The significant and strong effect of environmental beliefs on ecotour attitudes (H4) was in turn the most predictable, corroborating the findings of studies such as Falk and Hagsten [47], Ong and Musa [48], and Tonge et al. [49]. According to these studies, tourists with positive environmental attitudes tend to display a stronger desire to experience nature-based activities.

A direct effect of environmental attitudes on WTP could not be corroborated, and consequently H3 was not supported. On the one hand, this was unexpected as most of the extant literature on tourists’ attitudes and sustainable behaviour suggests that the stronger tourist attitudes towards sustainability are, the more likely they are to value sustainable tourism practices (and presumably pay for them). The study of Kim and Weiler [46], for instance, shows that nature-based areas tend to attract tourists with high levels of environmental attitudes and who support management approaches aimed at achieving sustainability objectives (in that case, responsible fossil collection). Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that such visitors would be willing to pay more to visit places where sustainability practices are adopted. Accordingly, Mohaidin, Wei, and Murshid [44] concluded that along with motivation and word–of–mouth, environmental attitudes significantly influence tourists’ intention to select sustainable tourism destinations, which again suggests that these factors might have a significant effect on tourists’ WTP to experience such destinations in comparison to those that do not adopt sustainable practices. Moreover, in the specific context of scuba diving tourism Ong and Musa [48] concluded that attitudes are an important factor influencing pro-environmental behaviour. Finally, when looking into ecotourism trips specifically Meleddu and Pulina [58] concluded that environmental beliefs have a positive impact on willingness to pay a premium price.

On the other hand, the results here are somewhat comprehensible considering the findings of several other previous studies. First, in Levine and Strube’s [43] experiment with college students, only explicit attitudes were strongly linked to intentions, which then mediated their effect on behaviour. Moreover, several studies evidence an eventual lack of coherence between tourists’ stated environmental attitudes and their effective consumption choices, e.g., [53,54], which further elucidates the absence of a direct effect between environmental attitudes and WTP. In line with these contributions, although this direct effect was not verified, the indirect effect was clearly evidenced by our model’s testing procedures. Namely, the effect was mediated by ecotour attitudes (H5) and sustainable consumption behaviour (H6), as both significantly affected WTP. The positive relationship between ecotour attitudes and WTP corroborates the results of several previous studies, showing that equivalent or related variables affect this construct. Such variables include tourists’ level of education [7] (in the context of nature-based tourism), awareness of ecotourism [58] (in the context of ecotourism), and the knowledge that money spent will finance biodiversity conservation and environmental protection [61] (in the context of entrance fees to protected areas). Moreover, the path Environmental Beliefs → Ecotour Attitudes → WTP is in line with the model tested by Hultman, Kazeminia, and Ghasemi [57], which validated these exact relationships in the context of ecotourism, although in the mentioned study the effect of environmental beliefs on ecotourism attitudes was externally mediated by tourism motivation.

6. Conclusions

The findings discussed above provide some original theoretical contributions which in turn lead to useful managerial insights for tourism industry stakeholders. These are discussed along with the study’s limitations and suggestions for further research in the following sections.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

The demonstration of the significant effects of ecotour attitudes and sustainable consumption behaviour on WTP represent an original contribution of the present research. As addressed in the literature review, both sustainability attitudes (including ecotour attitudes and environmental beliefs or equivalent constructs) and WTP have been separately addressed in previous studies. However, the relationship between these two sets of constructs has not been empirically addressed before. Naturally, such relationships have been addressed in more specific contexts such as ecotourism [58], scuba diving tourism [48], and visits to protected areas [61,62,72], although restricted to a single tourism product or motivation and not within a general causal model for WTP for sustainability in tourist destinations. In this context, the present investigation expands on the findings of studies such as Khalifa [36] and Cucculelli and Goffi [37], which demonstrated that sustainable practices are related to destination competitiveness. Furthermore, the present study links these findings with those of studies such as Mohaidin, Wei, and Murshid [44], who showed that environmental attitudes are positively correlated with the intention to select sustainable tourist destinations. The present study sheds light on tourists’ attitudes towards sustainability and how such attitudes affect willingness to pay for sustainable practices at tourism destinations. This paper therefore contributes to filling the knowledge gap pointed out by authors like Font and McCabe [25], who observe that in order to be truly sustainable tourist destinations and services require the support of consumers.

More specific theoretical contributions stem from the variables addressed within the model and their respective items. First, three new items were added to the initial list and validated by the measurement model assessment procedures, namely, “I am willing to pay more for a destination where local products are prioritised over mass-produced ones”, “I am willing to pay more to visit a destination that includes local producers in the tourism business supply chain (e.g., as suppliers to hotels and restaurants)”, and “I am willing to pay more to visit a destination that is not too crowded with tourists”. These should be considered in future studies on the topic. Accordingly, the sustainable consumption behaviour construct was originally included and validated in a WTP model within the present investigation. As both the construct’s internal consistency and its significant effect on WTP have been verified, this variable could be considered in future studies addressing willingness to pay for sustainability in tourist destinations as well.

6.2. Managerial Implications

The theoretical contributions addressed above lead to useful managerial implications, as they provide insights on how destinations and services can achieve the support of customers with positive attitudes towards sustainable consumption and sustainable tourism. Convincing a customer to do anything requires offering them a value proposition [57]. How much value a consumer attributes to a brand is dictated by how the product it promotes meets their needs and desires as well as by how that brand’s values align with a consumer’s own values [73]. Therefore, considering that tourism sustainability can be driven by demand [35], the results of the present study provide useful guidelines for destination managers aiming to cater to such demand.

Combining these results with the addressed contributions from the marketing and sustainable tourism literature, it can be inferred that in order to achieve consumer support and consequently competitiveness, destinations that adopt sustainable practices must first target tourists with a high degree of environmental beliefs and positive attitudes towards ecotourism. Moreover, within their promotional strategy they must appeal to these attitudes in order to demonstrate that they share these consumers’ values and are genuinely engaged in achieving sustainability goals, rather than simply in greenwashing. A promising way of doing this is through content marketing, namely the production of informative and values-oriented content. If well-planned and executed such actions are likely to convince tourists that the destination is engaged in enhancing their sustainability performance, which will help them with their travel decisions. Ultimately, such endeavours must seek to attract a tourist profile that fits the destination’s target audience and is willing to pay a premium price for the sustainability practices it adopts. In the case of hotels, for example, marketing managers should remember that a green hotel’s favourable image positively contributes to consumers’ behavioural intentions, and that such an overall image is positively affected by cognitive image elements [33]. In this context, providing informative content about the hotel’s sustainable practices is a good way to achieve support from more environmentally- and socially-aware consumers.

Another interesting managerial implication stems from the demonstrated relationship between sustainable consumption behaviour and WTP. In the era of digital marketing, big data plays a fundamental role in the strategic decisions of businesses and communication campaigns. In this context, knowing that customers who give preference to products with certain traits and companies with certain postures and are willing to pay more to visit a destination where sustainable practices are adopted is of great value for destination managers. This opens doors for more informed communication strategies, increasing the chances that messaging about a destination reaches the potential tourists to whom it is relevant. In sum, these two practical implications have the potential to increase sustainable tourist destinations’ competitiveness by allowing them to target the right travellers and communicate more effectively with them, delivering relevant messages and showing that they share their values.

Additional practical implications stem from the new items added to the WTP construct related to the prioritisation of local products and the inclusion of local producers in the tourism supply chain. The more obvious implication is the inclusion of such practices within the communication tools and strategies, as suggested above. However, in order to generate more effective insights into how to properly market sustainable tourist destinations and services these findings must be combined with those of previous studies. For instance, the results of Araújo et al. [64] suggest that willingness to pay for sustainable practices in tourist destinations is positively related to these practices’ effect on the quality of the tourist experience. Considering this, when promoting sustainable practices destinations and businesses must highlight those practices’ role on tourist experiences, especially in cases in which such a role might not be obvious. When addressing the inclusion of local producers in the tourism supply chain (in an Instagram post, for example), the easiest path would be to lecture potential customers about aspects such as the reduced “food miles” or the benefits to local farmers that result from sourcing food locally. However, considering the mentioned contribution, hotels and restaurants should highlight such aspects as increased freshness, healthiness, and flavour of fruits, vegetables, and meats used in the dishes they serve, as these have a clear effect on tourist experience. A similar logic can be applied to the prioritisation of local products, whether typical foods, handicrafts, or clothing. The same approach must be taken when considering the attitudes and behavioural aspects that have been shown to significantly affect WTP. The sustainable consumption behaviour construct, for instance, includes items related to giving preference to organisations that offer good conditions for workers and care about care about working conditions throughout their supply chain. These are the types of sustainable practices that imply additional operational costs for tourism businesses and are often overlooked by consumers, as their effect on tourist experience is not obvious. In this context, hotels, for instance, should focus on the genuine sympathy and goodwill of their well-paid and well-treated employees, rather than simply bragging about paying above-average salaries.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its clear contributions, the present investigation has several limitations. The first shortcoming stems from the cross-sectional nature of the study, which limits generalization of the results of the tested model. The unsupported direct relationship between environmental beliefs and WTP is another limitation. In this context, future studies should test this model in other settings in order to verify whether there are significant differences in effects between the latent variables and more specifically whether environmental beliefs might directly affect WTP in a different context.

Another limitation stems from the modest R2 value reached by WTP, which indicates that although ecotour attitudes and sustainable consumption behaviour do have a significant effect on it, this effect is not enough to explain a satisfactory portion of its variance. In other words, these attitudes and behaviours are not the only determinants of WTP for sustainability in tourism destinations. Naturally, previous studies have demonstrated that the awareness of being in a protected area [61] and the number of animal species sighted [7], as well as place attachment [49], for instance, affect WTP. However, those are context-specific variables rather than common traits or behaviour patterns that can be modelled in a general causal model for sustainable tourism. On the other hand, other studies (although addressing WTP or very close constructs such as willingness to accept economic sacrifices to protect the environment in specific contexts such as ecotourism and nature-based tourism) address the role of individual attitudes that have not been examined in the present investigation. These include subjective norms [58], environmental concern [63], and climate change-related risk perceptions [8]. Therefore, a fertile avenue for future investigation could consist of building on these findings and attempting to model the role of other determinants of WTP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.F.d.A., M.I.A.M. and M.T.R.C.; methodology: A.F.d.A. and A.L.V.; Data collection: A.F.d.A. and M.I.A.M.; Data analysis: A.F.d.A.; Writing—original draft preparation: A.F.d.A., M.T.R.C. and M.I.A.M.; Writing—review and editing: A.F.d.A., M.T.R.C. and M.I.A.M.; Visualization: A.F.d.A., M.T.R.C. and M.I.A.M.; Supervision: A.F.d.A. and M.I.A.M.; Project administration: A.F.d.A. and M.I.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by CO-FAC—Cooperativa de Formação e Animação Cultural, C.R.L., and by the Research Unit on Governance, Competitiveness and Public Policies (GOVCOPP) of the University of Aveiro.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this paper were collected by its authors through an online survey and are available to anyone upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone involved in this research project, especially all the students of the bachelor’s degree in Tourism and Management of Tourism Companies of Lusófona do Porto University, which actively participated in the research process. We would also like to thank our research units, TRIE and GOVCOPP for all the support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lebon, C. Tourism and Sustainability: Development, Globalisation and New Tourism in the Third World, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism Definitions; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Tourism for Development Guidebook; European Commission, Directorate-General Development and Cooperation: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. Identifying tourists with smaller environmental footprints. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galati, A.; Thrassou, A.; Christofi, M.; Vrontis, D.; Migliore, G. Exploring travelers’ willingness to pay for green hotels in the digital era. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetaram, N.; Song, H.; Ye, S.; Page, S. Estimating willingness to pay air passenger duty. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 72, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendran, A.; Sekar, C. An economic analysis of willingness to pay (WTP) for conserving the biodiversity. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2010, 37, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, A.; Fatorić, S.; Seekamp, E.; Smith, J.W.; Kanazawa, M.; Davenport, M.A. The Influences of Place Meanings and Risk Perceptions on Visitors’ Willingness to Pay for Climate Change Adaptation Planning in a Nature-Based Tourism Destination. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2018, 36, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynisdottir, M.; Song, H.; Agrusa, J. Willingness to pay entrance fees to natural attractions: An Icelandic case study. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. Assessing progress of tourism sustainability: Developing and validating sustainability indicators. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kim, J.; Lee, T. Collaboration for Community-Based Cultural Sustainability in Island Tourism Development: A Case in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Hall, C.M.; Esfandiar, K.; Seyfi, S. A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A. Nature-based Tourism and Environmental Sustainability in South Africa. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 136–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Cárdenas-García, P.J.; Espinosa-Pulido, J.A. Does environmental sustainability contribute to tourism growth? An analysis at the country level. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 213, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowburn, B.; Moritz, C.; Birrell, C.; Grimsditch, G.; Abdulla, A. Can luxury and environmental sustainability co-exist? Assessing the environmental impact of resort tourism on coral reefs in the Maldives. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 158, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Fan, D.X.F.; Lyu, J.; Lin, P.M.C.; Jenkins, C.L. Analyzing the Economic Sustainability of Tourism Development: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 43, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gené, J.; Sánchez-Pulido, L.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Daries, N. The Economic Sustainability of Snow Tourism: The Case of Ski Resorts in Austria, France, and Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smyczek, S.; Festa, G.; Rossi, M.; Monge, F. Economic sustainability of wine tourism services and direct sales performance—Emergent profiles from Italy. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1519–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI: Oxon, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Boussaa, D. The past as a catalyst for cultural sustainability in historic cities; the case of Doha, Qatar. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 27, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, N.; Laing, J.; Mair, J. Social capital as a heuristic device to explore sociocultural sustainability: A case study of mountain resort tourism in the community of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, USA. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 23, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzner, M. Spatially Disaggregated Cultural Consumption: Empirical Evidence of Cultural Sustainability from Austria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, X.; McCabe, S. Sustainability and marketing in tourism: Its contexts, paradoxes, approaches, challenges and potential. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nadalipour, Z.; Khoshkhoo, M.H.I.; Eftekhari, A.R. An integrated model of destination sustainable competitiveness. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2019, 29, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Segmenting the rural tourist market by sustainable travel behaviour: Insights from village visitors in Portugal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazytė, K.; Weber, F.; Schaffner, D. Sustainability Management of Hotels: How Do Customers Respond in Online Reviews? J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 18, 282–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliner, M.; Monferrer, D.; Estrada, M.; Rodríguez, R.M. Environmental Sustainability and the Hospitality Customer Experience: A Study in Tourist Accommodation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ponnapureddy, S.; Priskin, J.; Ohnmacht, T.; Vinzenz, F.; Wirth, W. The influence of trust perceptions on German tourists’ intention to book a sustainable hotel: A new approach to analysing marketing information. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 970–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinzenz, F.; Priskin, J.; Wirth, W.; Ponnapureddy, S.; Ohnmacht, T. Marketing sustainable tourism: The role of value orientation, well-being and credibility. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinzenz, F. The added value of rating pictograms for sustainable hotels in classified ads. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hsu, L.-T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia-Jung, C.; Pei-Chun, C. Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Green Hotel Attributes in Tourist Choice Behavior: The Case of Taiwan. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 937–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brau, R. Demand-Driven Sustainable Tourism? A Choice Modelling Analysis. Tour. Econ. 2008, 14, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalifa, G.S.A. Factors Affecting Tourism Organization Competitiveness: Implications for the Egyptian Tourism Industry. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2020, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucculelli, M.; Goffi, G. Does sustainability enhance tourism destination competitiveness? Evidence from Italian Destinations of Excellence. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 111, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Sánchez, Y.; Pulido-Fernández, J.I. In search of the pro-sustainable tourist: A segmentation based on the tourist “sustainable intelligence”. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintunde, E. Theories and Concepts for Human Behavior in Environmental Preservation. J. Environ. Sci. Public Heal. 2017, 1, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, M.; Hall, C.; Han, H. Behavioral Influences on Crowdfunding SDG Initiatives: The Importance of Personality and Subjective Well-Being. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Bonn, M.; Hall, C.M. Traveler Biosecurity Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects of Intervention, Resilience, and Sustainable Development Goals. J. Travel Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Schultz, P.W.; Scheuthle, H. The Theory of Planned Behavior Without Compatibility? Beyond Method Bias and Past Trivial Associations. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1522–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.S.; Strube, M.J. Environmental Attitudes, Knowledge, Intentions and Behaviors Among College Students. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 152, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaidin, Z.; Wei, K.T.; Murshid, M.A. Factors influencing the tourists’ intention to select sustainable tourism destination: A case study of Penang, Malaysia. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2017, 3, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Airey, D.; Szivas, E. The Multiple Assessment of Interpretation Effectiveness: Promoting Visitors’ Environmental Attitudes and Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2010, 50, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, A.K.; Weiler, B. Visitors’ attitudes towards responsible fossil collecting behaviour: An environmental attitude-based segmentation approach. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.; Hagsten, E. Climate zone crucial for efficiency of ski lift operators. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 664–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ong, T.F.; Musa, G. An examination of recreational divers’ underwater behaviour by attitude–behaviour theories. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonge, J.; Ryan, M.M.; Moore, S.A.; Beckley, L.E.; Pearce, J. The Effect of Place Attachment on Pro-environment Behavioral Intentions of Visitors to Coastal Natural Area Tourist Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; Higgins, B.R. Ecotourism Market and Industry Structure. In Ecotourism: A Guide for Planners and Mangers; The Ecotourism Society: North Bennington, VE, USA, 1997; pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, J. The New Environmental Paradigm and Nature-Based Tourism Motivation. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H.; Tseng, C.H.; Lin, Y.F. Segmentation by recreation experience in island-based tourism: A case study of Taiwan’s Liuqiu Island. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. Overnight Ecotourist Market Segmentation in the Gold Coast Hinterland of Australia. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budeanu, A. Sustainable tourist behaviour? A discussion of opportunities for change. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Tyllianakis, E.; Luisetti, T.; Ferrini, S.; Turner, R.K. Prospective tourist preferences for sustainable tourism development in Small Island Developing States. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring consumer attitude and behaviour towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, K.G.M.; Kazeminia, A.; Ghasemi, V. Intention to visit and willingness to pay premium for ecotourism: The impact of attitude, materialism, and motivation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleddu, M.; Pulina, M. Evaluation of individuals’ intention to pay a premium price for ecotourism: An exploratory study. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2016, 65, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Rivas, C.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. Willingness to Pay for More Sustainable Tourism Destinations in World Heritage Cities: The Case of Caceres, Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agag, G.; Brown, A.; Hassanein, A.; Shaalan, A. Decoding travellers’ willingness to pay more for green travel products: Closing the intention–behaviour gap. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1551–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.-W.; Jia, J.-B. Tourists’ willingness to pay for biodiversity conservation and environment protection, Dalai Lake protected area: Implications for entrance fee and sustainable management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2012, 62, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, L.F.; Langford, I.H.; Kenyon, W. Valuing marine parks in a developing country: A case study of the Seychelles. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2003, 8, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, T. The impact of values, environmental concern, and willingness to accept economic sacrifices to protect the environment on tourists’ intentions to buy ecologically sustainable tourism alternatives. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.; De Marques, I.A.; Candeias, T.; Vieira, L.A. Tourists’ Willingness to Pay for Environmental and Sociocultural Sustainability in Destinations: Underlying Factors and the Effect of Age. In Transcending Borders in Tourism Through Innovation and Cultural Heritage 8th International Conference, IACuDIT, Hydra, Greece, 1–3 September 2021; Katsoni, V., Serban, A.C., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics: Hydra, Greece, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, B.; Alvarez, M.D. Understanding the Tourists’ Perspective of Sustainability in Cultural Tourist Destinations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.L. ABC Do LISREL Interactivo, 1st ed.; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentler, P.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Cudeck, R.; Iacobucci, D. Structural Equations Modeling—SEM Using Correlation or Covariance Matrices. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 10, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, L.E.; Kurtz, D.L. Contemporary Marketing, 16th ed.; Thomson South-Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Kartajaya, H.; Setiawan, I. Marketing 4.0: Moving from Traditional to Digital; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).