Strategic Allocation of Development Projects in Post-Conflict Regions: A Gender Perspective for Colombia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: Are international development programs located in regions that have historically experienced conflict in Colombia?

- RQ2: Are development projects with gender as a significant objective located in regions that have historically experienced conflict in Colombia?

- RQ3: Can gender characteristics of the population explain the relationship between conflicts and the geographic allocation of development programs?

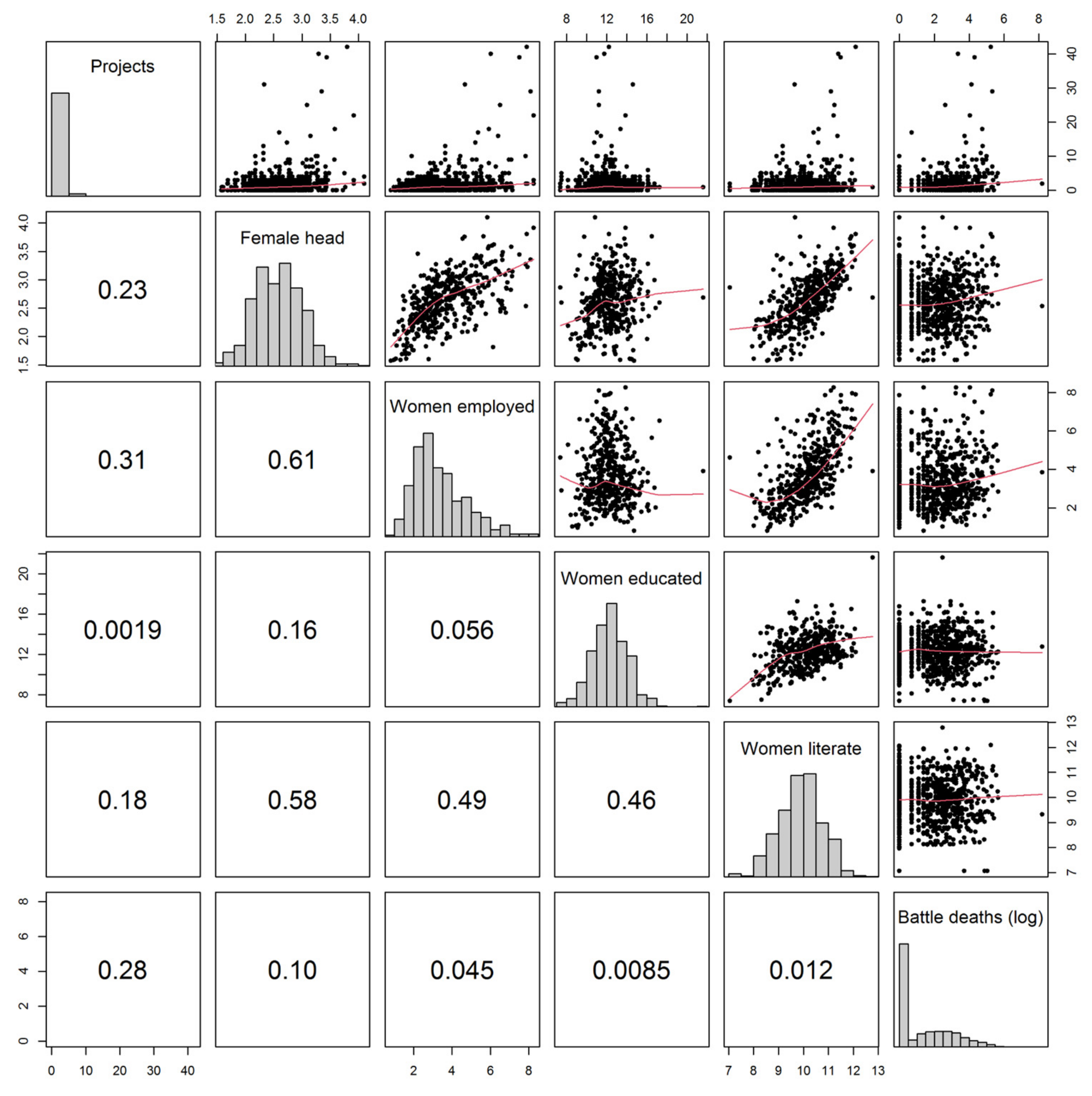

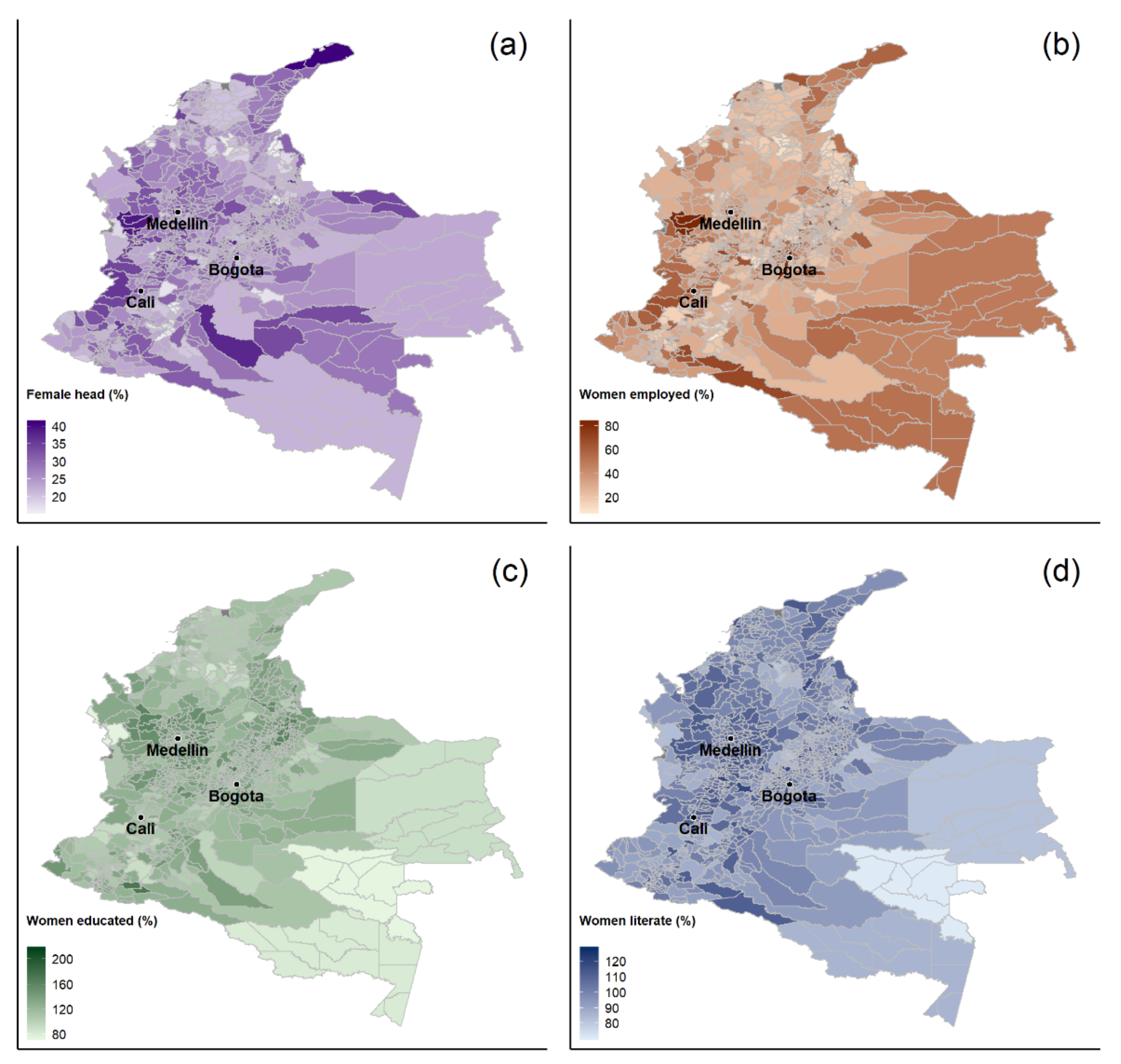

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

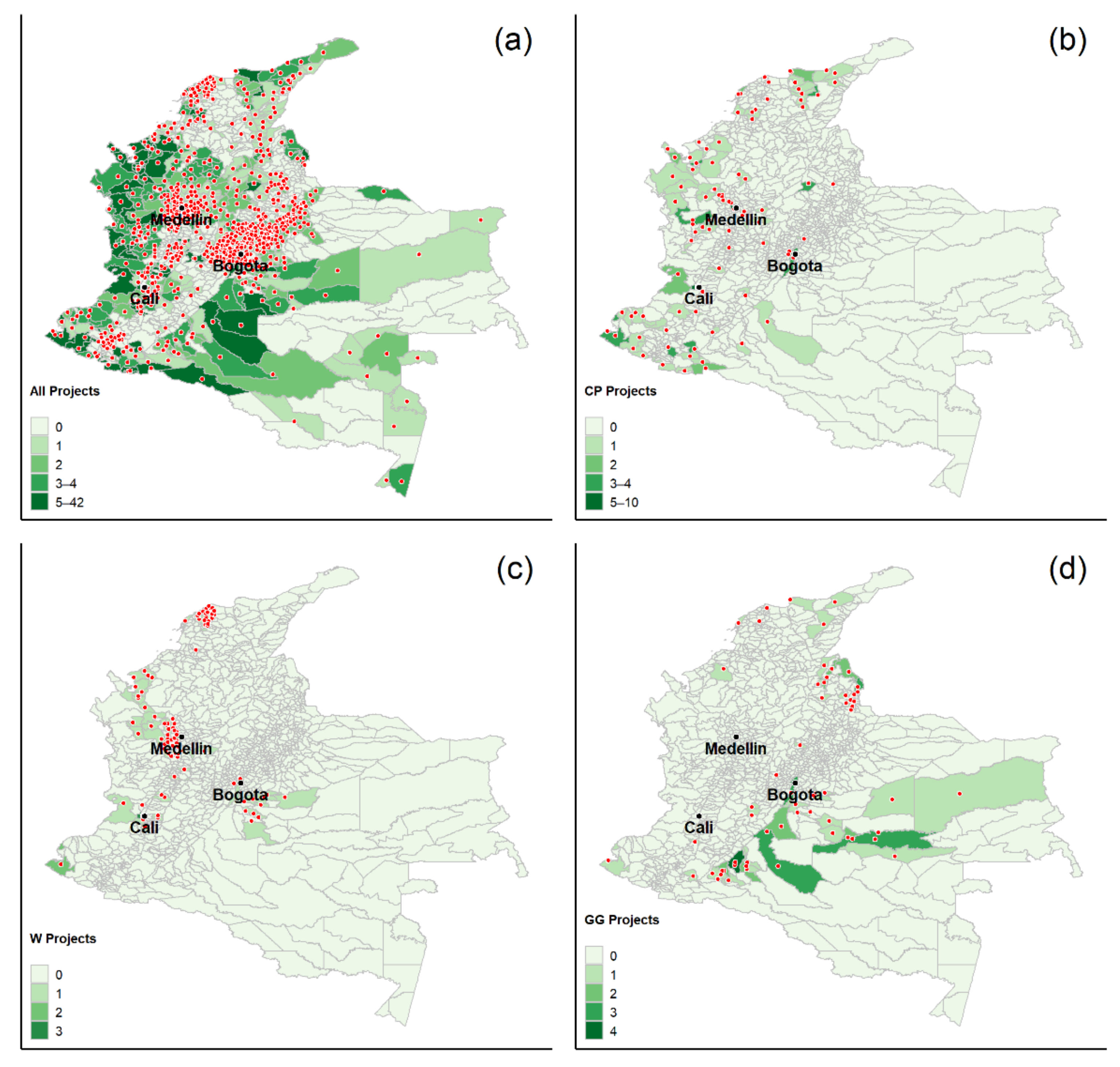

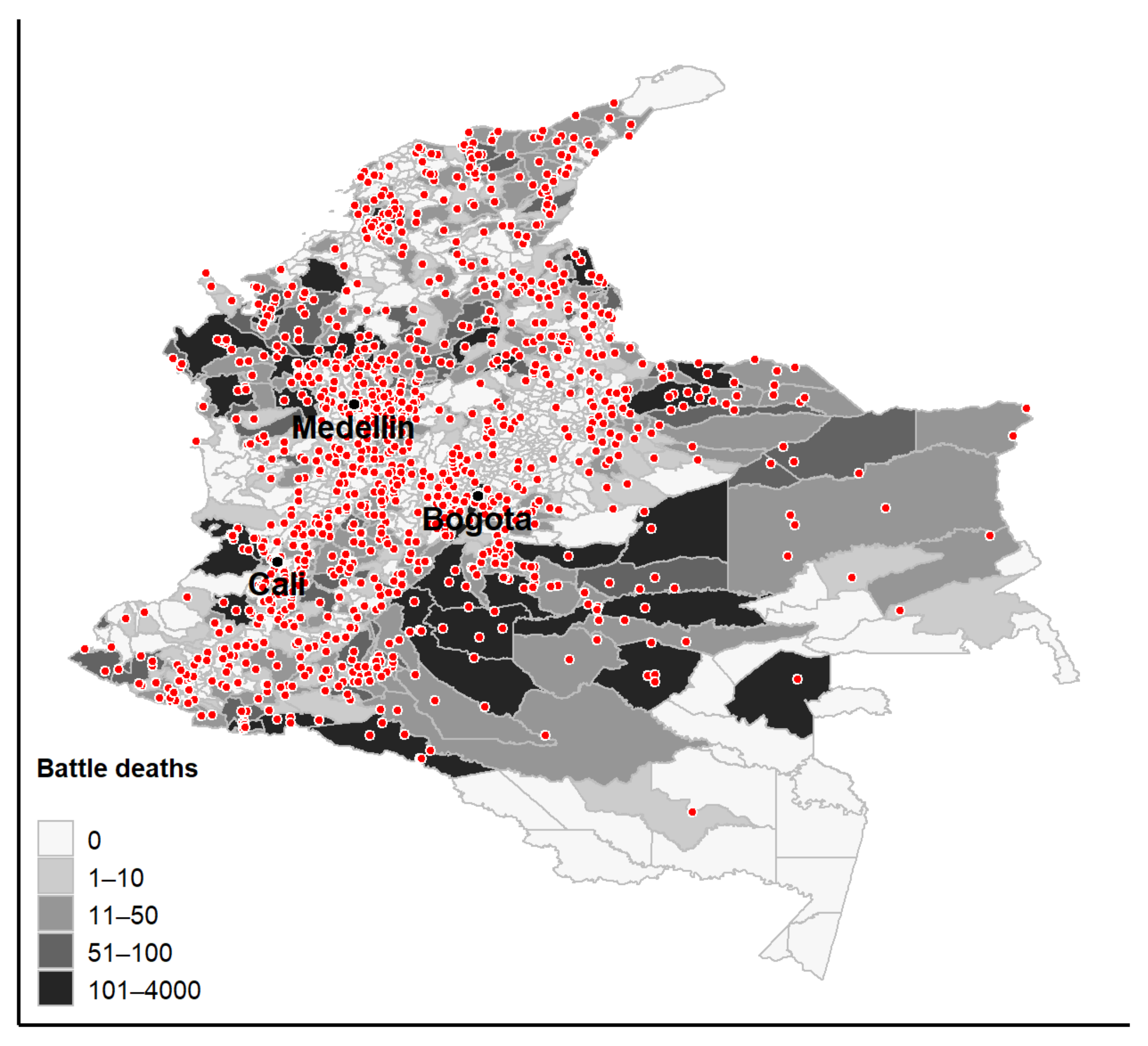

3.1. All Projects

3.2. Projects with Gender as a Significant Objective

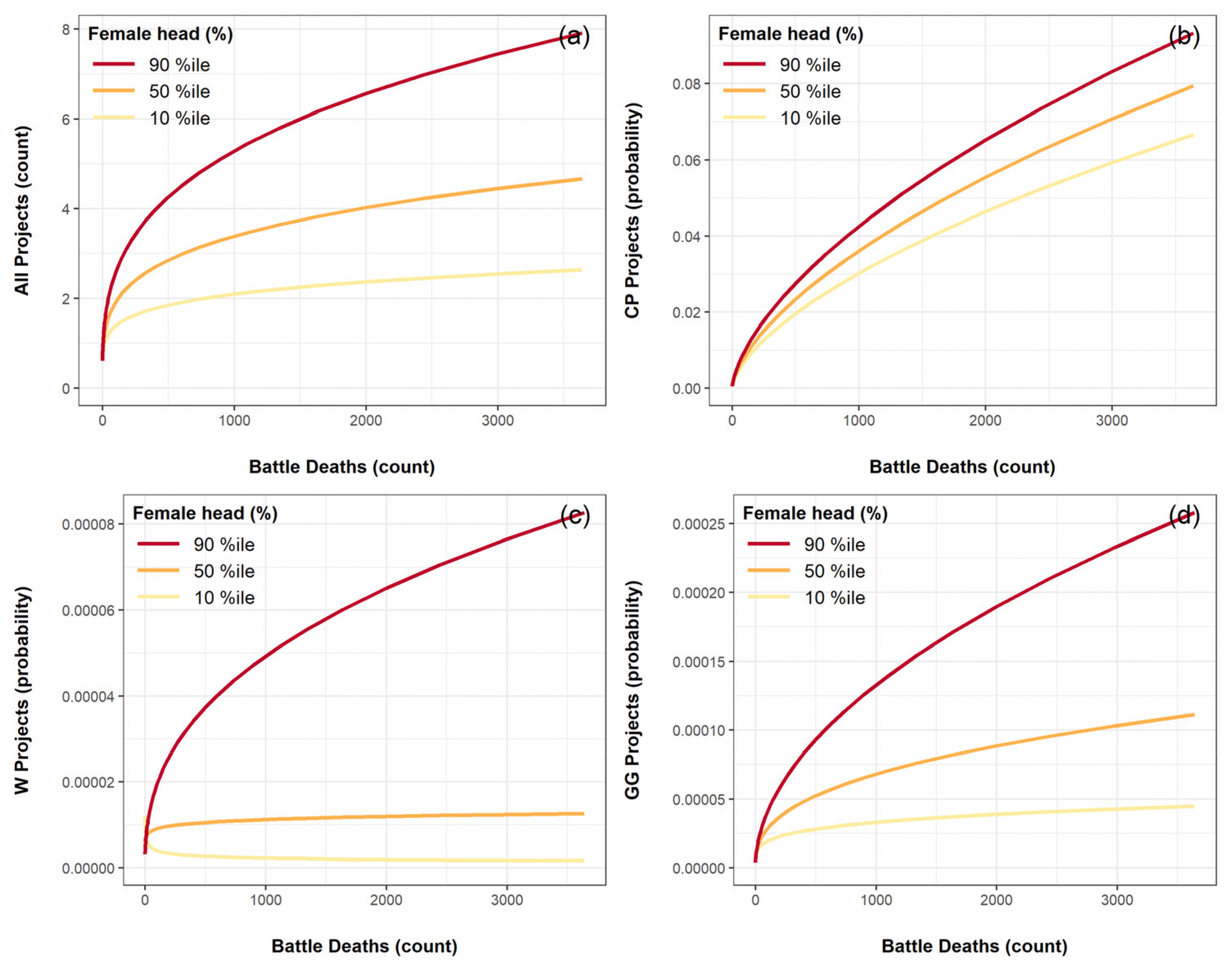

3.3. Interactions

3.4. Robustness Tests

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Projects | CP Projects | W Projects | GG Projects | |||||

| b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Intercept | 1.24 | 0.11 | 0.44 | ** | −0.21 | |||

| Battle deaths | 0.58 | *** | 0.05 | *** | 0.01 | + | 0.01 | * |

| Female head a | 0.55 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | ||||

| Women employed a | 0.57 | ** | 0.02 | 0.03 | + | 0.01 | ||

| Women educated a | −0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Women literate a | −0.34 | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0 | ||||

| Administrative performance a | 0.35 | + | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |||

| Average precipitation | −0.06 | 0 | −0.05 | 0.01 | ||||

| Average temperature | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Distance to road | 0.05 | * | 0.01 | ** | 0 | 0 | ||

| Night-time lights | 0.36 | ** | 0.03 | ** | 0 | 0.01 | + | |

| Coca production | 0.47 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.01 | ||||

| Wealth index | −0.3 | −0.02 | −0.02 | + | −0.01 | |||

| Conflict migrants a | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.16 | 0.03 | ||||

| Young children | 0.13 | 0.31 | −0.04 | −0.06 | ||||

| Model statistics | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.32 | ||||

| AIC | 5312 | 49 | −205 | −597 | ||||

| N | 1097 | 1097 | 1097 | 1097 | ||||

Appendix C

| All Projects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Intercept | 0.87 | ** | 3.09 | |

| Battle deaths | 0.68 | *** | 0.57 | *** |

| Female head a | 1.55 | |||

| Women employed a | 0.62 | * | ||

| Women educated a | 0.16 | |||

| Women literate a | −0.95 | * | ||

| Administrative performance a | −0.31 | |||

| Average precipitation | 0.02 | |||

| Average temperature | 0.06 | |||

| Distance to road | 0.05 | * | ||

| Night-time lights | 0.19 | |||

| Coca production | 0.58 | |||

| Wealth index | −0.17 | |||

| Conflict migrants a | 0.14 | |||

| Young children | 4.53 | |||

| Model statistics | ||||

| R2 | 0.27 | 0.32 | ||

| AIC | 6091 | 5927 | ||

| N | 1120 | 1097 | ||

Appendix D

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Projects | ||||

| b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Intercept | −0.05 | −1.6 | ||

| Battle deaths | 0.34 | *** | 0.28 | *** |

| Female head a | 0.24 | |||

| Women employed a | 0.13 | * | ||

| Women educated a | −0.02 | |||

| Women literate a | −0.08 | |||

| Administrative performance a | 0.14 | + | ||

| Average precipitation | 0.07 | |||

| Average temperature | 0.02 | |||

| Distance to road | 0.02 | ** | ||

| Night-time lights | 0.15 | ** | ||

| Coca production | 0.18 | |||

| Wealth index | 0.01 | |||

| Conflict migrants a | −0.13 | |||

| Young children | 1.02 | |||

| Model statistics | ||||

| Theta | 2.14 | 3.78 | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.4 | 0.51 | ||

| AIC | 3355 | 3158 | ||

| N | 1120 | 1097 | ||

Appendix E

| All Projects | CP Projects | W Projects | GG Projects | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | sig. | % omitted | % sig. | b | sig. | % omitted | % sig. | b | sig. | % omitted | % sig. | b | sig. | % omitted | % sig. | |

| Battle deaths | 0.26 | *** | 10 | 100 | 0.65 | *** | 10 | 100 | 0.19 | ** | 10 | 77 | 0.37 | ** | 10 | 93.8 |

| 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 62.8 | 20 | 78.1 | |||||||||

| 30 | 100 | 30 | 100 | 30 | 50 | 30 | 63 | |||||||||

Appendix F

References

- Pettersson, T.; Öberg, M. Organized Violence, 1989–2019. J. Peace Res. 2020, 57, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. States of Fragility 2018; OECD: Paris, France, 2018; ISBN 978-92-64-30206-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J.; Witt, A.; Stappenbeck, J.; Peez, A.; Junk, J.; Coni-Zimmer, M.; Christian, B.; Birchinger, S.; Bethke, F. Frieden und Entwicklung 2020: Eine Analyse Aktueller Erfahrungen und Erkenntnisse; Leibniz-Institut, Hessische Stiftung Friedens und Konfliktforschung (HSFK), Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF): Frankfurt, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bluhm, R.; Gassebner, M.; Langlotz, S.; Schaudt, P. Fueling Conflict? (De)Escalation and Bilateral Aid. J. Appl. Econom. 2021, 36, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Hoeffler, A. AID, Policy and Peace: Reducing the Risks of Civil Conflict. Def. Peace Econ. 2002, 13, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ree, J.; Nillesen, E. Aiding Violence or Peace? The Impact of Foreign Aid on the Risk of Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Dev. Econ. 2009, 88, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingebiel, S. The Impact of Development Co-Operation in Conflict Situations: German Experience in Six Countries. Evaluation 2001, 7, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, N.; Qian, N. US Food Aid and Civil Conflict. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1630–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, A. Countries in Violent Conflict and Aid Strategies: The Case of Sri Lanka. World Dev. 2002, 30, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Savun, B.; Tirone, D.C. Exogenous Shocks, Foreign Aid, and Civil War. Int. Organ. 2012, 66, 363–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürcher, C. What Do We (Not) Know About Development Aid and Violence? A Systematic Review. World Dev. 2017, 98, 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhnke, J.R.; Zürcher, C. Aid, Minds and Hearts: The Impact of Aid in Conflict Zones. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 2013, 30, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crost, B.; Felter, J.; Johnston, P. Aid Under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 1833–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wencker, T.; Verspohl, I. German Development Cooperation in Fragile Contexts; German Institute for Development Evaluation (DEval): Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.M.; Sullivan, C. Doing Harm by Doing Good? The Negative Externalities of Humanitarian Aid Provision during Civil Conflict. J. Polit. 2015, 77, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürcher, C. The Folly of “Aid for Stabilisation”. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, K.; Kaplan, L.C.; Wong, M. China and the World Bank: How Contrasting Development Approaches Affect State Stability; Aid Data Working Paper; AidData at William & Mary: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Weezel, S. A Spatial Analysis of the Effect of Foreign Aid in Conflict Areas; AidData Working Paper; AidData at William & Mary: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Child, T.B. Conflict and Counterinsurgency Aid: Drawing Sectoral Distinctions. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 141, 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, R.M.; Molfino, E. Aiding Victims, Abetting Violence: The Influence of Humanitarian Aid on Violence Patterns During Civil Conflict. J. Glob. Secur. Stud. 2016, 1, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Dollar, D. Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why? J. Econ. Growth 2000, 5, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maizels, A.; Nissanke, M.K. Motivations for Aid to Developing Countries. World Dev. 1984, 12, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, E.; Reinhardt, G.Y. Giving and Receiving Foreign Aid: Does Conflict Count? World Dev. 2008, 36, 2566–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Dollar, D. Aid Allocation and Poverty Reduction. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2002, 46, 1475–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavire, G.; Nunnenkamp, P.; Thiele, R.; Triveño, L. Assessing the Allocation of Aid: Developmental Concerns and the Self-Interest of Donors. Indian Econ. J. 2006, 54, 26–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthélemy, J.-C. Bilateral Donors’ Interest vs. Recipients’ Development Motives in Aid Allocation: Do All Donors Behave the Same? Rev. Dev. Econ. 2006, 10, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnside, C.; Dollar, D. Aid, Policies, and Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, P. Armed Conflict, Terrorism, and the Allocation of Foreign Aid. Econ. Peace Secur. J. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhler, H.; Nunnenkamp, P. Needs-Based Targeting or Favoritism? The Regional Allocation of Multilateral Aid within Recipient Countries: Needs-Based Targeting or Favoritism? Kyklos 2014, 67, 420–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, R.S. How Aid Targets Votes: The Impact of Electoral Incentives on Foreign Aid Distribution. World Polit. 2014, 66, 293–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodler, R.; Raschky, P.A. Regional Favoritism. Q. J. Econ. 2014, 129, 995–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaki, T. The Political Economy of Aid Allocation in Africa: Evidence from Zambia. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2018, 61, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, P.; Braithwaite, A. Locating Foreign Aid Commitments in Response to Political Violence. Public Choice 2016, 169, 333–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenman, P.; Ehrenpreis, D. Results of the OECD DAC/Development Centre Experts’ Seminar on “Aid Effectiveness and Selectivity: Integrating Multiple Objectives into Aid Allocations”. DAC J. 2003, 4, 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dipendra, K.C. Which Aid Targets Poor at the Sub-National Level? World Dev. Perspect. 2020, 17, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francken, N.; Minten, B.; Swinnen, J.F.M. The Political Economy of Relief Aid Allocation: Evidence from Madagascar. World Dev. 2012, 40, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruttan, V.W. Integrated Rural Development Programmes: A Historical Perspective. World Dev. 1984, 12, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, A.; Gehring, K.; Klasen, S. Gesture Politics or Real Commitment? Gender Inequality and the Allocation of Aid. World Dev. 2015, 70, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kleemann, L.; Nunnenkamp, P.; Thiele, R. Gender Inequality, Female Leadership and Aid Allocation: A Panel Analysis of Aid for Education. J. Int. Dev. 2016, 28, 376–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.C. Does Foreign Aid Target the Poorest? Int. Organ. 2017, 71, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsadam, A.; Østby, G.; Rustad, S.A.; Tollefsen, A.F.; Urdal, H. Development Aid and Infant Mortality. Micro-Level Evidence from Nigeria. World Dev. 2018, 105, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustad, S.; Hoelscher, K.; Østby, G.; Urdal, H. Does Development Aid Address Political Exclusion? A Disaggregated Study of the Location of Aid in Sub-Saharan Africa; AidData Working Paper; AidData at William & Mary: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Platteau, J.-P.; Gaspart, F. The Risk of Resource Misappropriation in Community-Driven Development. World Dev. 2003, 31, 1687–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Melo, M.E. Peace in Colombia Is Also a Women’s Issue. Multidiscip. J. Gend. Stud. 2016, 5, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kreft, A.-K. Responding to Sexual Violence: Women’s Mobilization in War. J. Peace Res. 2019, 56, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, F.; Solimano, A.; Formisano, M. Conflict, Violence and Crime in Colombia. Underst. Civ. War 2005, 2, 119–159. [Google Scholar]

- Brüntrup-Seidemann, S.; Gantner, V.; Heucher, A.; Wiborg, I. Förderung der Gleichberechtigung der Geschlechter in Post-Konflikt-Kontexten; Deutsches Evaluierungsinstitut der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit (DEval): Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra, J.R.; González, J.C. Colombia y El Acuerdo de Paz Con Las FARC-EP: Entre La Paz Territorial Que No Llega y La Violencia Que No Cesa. Rev. Esp. Cienc. Política 2021, 55, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Salazar, L. Armed Conflict and Territorial Configuration: Elements for the Consolidation of the Peace in Colombia. Bitacora Urbano Territ. 2016, 26, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga, J.F.; Hua, Y. A Gravity Model Analysis of Forced Displacement in Colombia. Cities 2019, 95, 102407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRW. World Report 2017; Human Rights Watch: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-60980-734-4. [Google Scholar]

- Plümper, T.; Neumayer, E. The Unequal Burden of War: The Effect of Armed Conflict on the Gender Gap in Life Expectancy. Int. Organ. 2006, 60, 723–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RUV. Registro Único de Víctimas (RUV). Available online: https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/es/registro-unico-de-victimas-ruv/37394 (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Acosta, M.; Castañeda, A.; García, D.; Hernández, F.; Muelas, D.; Santamaria, A. The Colombian Transitional Process: Comparative Perspectives on Violence against Indigenous Women. Int. J. Transit. Justice 2018, 12, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzate, M.M. The Sexual and Reproductive Rights of Internally Displaced Women: The Embodiment of Colombia’s Crisis. Disasters 2008, 32, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirtz, A.L.; Pham, K.; Glass, N.; Loochkartt, S.; Kidane, T.; Cuspoca, D.; Rubenstein, L.S.; Singh, S.; Vu, A. Gender-Based Violence in Conflict and Displacement: Qualitative Findings from Displaced Women in Colombia. Confl. Health 2014, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedemann-Sanchez, G.; Lovaton, R. Intimate Partner Violence in Colombia: Who Is at Risk? Soc. Forces 2012, 91, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, K.B.; Lemaitre, J. Internally Displaced Women as Knowledge Producers and Users in Humanitarian Action: The View from Colombia. Disasters 2013, 37, S36–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar-Restrepo, M.; Irazábal, C. Indigenous Women and Violence in Colombia: Agency, Autonomy, and Territoriality. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2014, 41, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNSC. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on Women, Peace and Security. In Understanding the Implications, Fulfilling the Obligations; United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325; United Nations Security Council: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- OSAGI. Landmark Resolution on Women, Peace and Security; Office of the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Transforming Our World. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Arostegui, J. Gender, Conflict, and Peace-Building: How Conflict Can Catalyse Positive Change for Women. Gend. Dev. 2013, 21, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo, J.M.; Wylie, K.N. Gender, Race, and Political Representation in Latin America. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo, E.; Romero, H.; Álvarez, M.; Vargas, J. Participation of Women in the Labor Market in Colombia: Challenges and Recent Trends. Rev. Espac. 2018, 39, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- BMZ. Gleichberechtigung Der Geschlechter in Der Deutschen Entwicklungspolitik: Übersektorales Konzept; Strategic Paper; Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung: Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Stat Extracts Database. Creditor Reporting System; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- BMZ. Hopes of Peace and Stability; Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung: Bonn, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AidData. Colombia AIMS Geocoded Research Release Level 1 v.1.1.1; AidData at William & Mary: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AidData. Financing the SDGs in Colombia; AidData at William & Mary: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Högbladh, S. UCDP GED Codebook Version 19.1; Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, R.; Melander, E. Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset. J. Peace Res. 2013, 50, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MPC. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.2 [Dataset]; Minnesota Population Center: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DNP-DDDR. Resultados de Desempeño Integral de Los Departamentos y Municipios de La Vigencia 2017; Desempeño Municipal; Departamento Nacional de Planeación (DNP), Dirección de Descentralización y Desarrollo Regional (DDDR), Gobierno de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S.; BenYishay, A.; Lv, Z.; Runfola, D. GeoQuery: Integrating HPC Systems and Public Web-Based Geospatial Data Tools. Comput. Geosci. 2019, 122, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Day/Night Band (DNB) [Dataset]; Earth Observation Group, NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI): Asheville, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- AidData. R&E Geocoding Methodology; Version 2.0.2; AidData at William & Mary: Williamsburg, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ziaja, S.; Grävingholt, J.; Kreibaum, M. Constellations of Fragility: An Empirical Typology of States. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2019, 54, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, C.; Lister, M. Introduction: Theories of the State. In The State: Theories and Issues; Hay, C., Lister, M., Marsh, D., Eds.; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-0-230-80227-8. [Google Scholar]

- Grown, C.; Addison, T.; Tarp, F. Aid for Gender Equality and Development: Lessons and Challenges. J. Int. Dev. 2016, 28, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of the Third Millennium Development Goal 1. Gend. Dev. 2005, 13, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; Mukherjee, A. No Empowerment without Rights, No Rights without Politics: Gender-Equality, MDGs and the Post-2015 Development Agenda. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2014, 15, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali Swain, R.; Garikipati, S.; Wallentin, F.Y. Does Foreign Aid Improve Gender Performance in Recipient Countries? J. Int. Dev. 2020, 32, 1171–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, E.; Palloni, A. Prevalence and Patterns of Female Headed Households in Latin America: 1970–1990. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 1999, 30, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.; Chant, S.; Linneker, B. Challenges and Changes in Gendered Poverty: The Feminization, De-Feminization, and Re-Feminization of Poverty in Latin America. Fem. Econ. 2019, 25, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DANE. UN Women Boletín Estadístico: Empoderamiento Económico de Las Mujeres En Colombia; Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística & UN Women: Bogota, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.G. Similarities and Differences: Female-Headed Households in Brazil and Colombia. In Where Did All the Men Go? Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 131–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez, A.M.; Moya, A. Vulnerability of Victims of Civil Conflicts: Empirical Evidence for the Displaced Population in Colombia. World Dev. 2010, 38, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meertens, D. Forced Displacement and Women’s Security in Colombia. Disasters 2010, 34, S147–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, R.; Díaz, Y.; Pardo, R. The Colombian Multidimensional Poverty Index: Measuring Poverty in a Public Policy Context. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 127, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.R. The Informal Labor Market in Colombia: Identification and Characterization. Rev. Desarro. Soc. 2009, 145–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, 3rd ed.; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Literacy Rate; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, J.R.; Hughes, B.B.; Irfan, M.T. Advancing Global Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Amarante, V.; Rossel, C. Unfolding Patterns of Unpaid Household Work in Latin America. Fem. Econ. 2018, 24, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators; Education at a Glance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; ISBN 978-92-64-80398-5. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.J.; Behrman, J.R. Gender Gaps in Educational Attainment in Less Developed Countries. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2010, 36, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardino, M.P. The Effect of Violence on the Educational Gender Gap; Universitat Pompeu Fabra: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Buhaug, H.; Lujala, P. Accounting for Scale: Measuring Geography in Quantitative Studies of Civil War. Polit. Geogr. 2005, 24, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.C. Poor Targeting: A Gridded Spatial Analysis of the Degree to Which Aid Reaches the Poor in Africa. World Dev. 2018, 103, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, M.; Mathonnat, J. What Can We Learn on Chinese Aid Allocation Motivations from Available Data? A Sectorial Analysis of Chinese Aid to African Countries. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 60, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, O.A.; Shultz, S.D. Poisson Count Models to Explain the Adoption of Agricultural and Natural Resource Management Technologies by Small Farmers in Central American Countries. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2000, 32, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, X.A. Using Observation-Level Random Effects to Model Overdispersion in Count Data in Ecology and Evolution. PeerJ 2014, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuur, A.F.; Leno, E.N.; Walker, N.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Statistics for Biology and Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-87458-6. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, P.D. Fixed Effects Regression Models; Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; SAGE: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-7619-2497-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Regression Analysis of Count Data, 2nd ed.; Econometric Society Monographs; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-107-66727-3. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, P.J. The Behavior of Maximum Likelihood Estimates under Nonstandard Conditions. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; Le Cam, L.M., Neyman, J., Eds.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1967; pp. 221–223. [Google Scholar]

- White, H. A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity. Econometrica 1980, 48, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F.C. Logistic Regression: A Primer; Sage University Papers Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7619-2010-6. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, P.; Hoeffler, A.; Söderbom, M. Post-Conflict Risks. J. Peace Res. 2008, 45, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sturman, M.C. Multiple Approaches to Analyzing Count Data in Studies of Individual Differences: The Propensity for Type I Errors, Illustrated with the Case of Absenteeism Prediction. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1999, 59, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxe, S.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. The Analysis of Count Data: A Gentle Introduction to Poisson Regression and Its Alternatives. J. Pers. Assess. 2009, 91, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oster, E. Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrotzki, R.J. The Politics of Environmental Concern: A Cross-National Analysis. Organ. Environ. 2012, 25, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiter, S.; De Graaf, N.D. National Context, Religiosity, and Volunteering: Results from 53 Countries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 71, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firchow, P. Must Our Communities Bleed to Receive Social Services? Development Projects and Collective Reparations Schemes in Colombia. J. Peacebuilding Dev. 2013, 8, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, O.; Nussio, E. Community Counts: The Social Reintegration of Ex-Combatants in Colombia. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 2018, 35, 132–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theidon, K. Transitional Subjects: The Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration of Former Combatants in Colombia. Int. J. Transit. Justice 2007, 1, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, A.C. Internal Displacement in Colombia: Humanitarian, Economic and Social Consequences in Urban Settings and Current Challenges. Int. Rev. Red Cross 2009, 91, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIZ. Promising Practices: On the Human Rights-Based Approach in German Development Cooperation Peace-Building: Support to Survivors of Gender-Based Violence and to Indigenous People in Colombia; Deutsche Gesellschaft für International Zusammenarbeit (GIZ): Bonn, Germany; German Institute for Human Rights: Eschborn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, M.E.; Zuckerman, E. The Gender Dimensions of Post-Conflict Reconstruction: The Challenges in Development Aid. In Making Peace Work; Addison, T., Brück, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2009; pp. 101–135. ISBN 978-1-349-30804-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hoveskog, M.; Preciado, D.J.S.; Ortiz, H.B.P. 21 Days of Change: Addressing the Post-War Consequences on Women’s Well-Being in Colombia; SAGE Publications; SAGE Business Cases Originals: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alther, G. Colombian Peace Communities: The Role of NGOs in Supporting Resistance to Violence and Oppression. Dev. Pract. 2006, 16, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnaala, E. Legacies of Violence and the Unfinished Past: Women in Post-Demobilization Colombia and Guatemala. Peacebuilding 2019, 7, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gender Association. The Other Side of the Mirror; Gender Associations International Consulting Group: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo, P.; Rocha Menocal, A.; Hinestroza, V. Progress despite Adversity: Women’s Empowerment and Conflict in Colombia; Overseas Development Institute (ODI): London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre, J.; Sandvik, K.B. Shifting Frames, Vanishing Resources, and Dangerous Political Opportunities: Legal Mobilization among Displaced Women in Colombia. Law Soc. Rev. 2015, 49, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaitre, J. Transitional Justice and the Challenges of a Feminist Peace. Int. J. Const. Law 2020, 18, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes-Báez, L.M.; Jaramillo Ruiz, F. ‘Peace without Women Does Not Go!’Women’s Struggle for Inclusion in Colombia’s Peace Process with the FARC. Colomb. Int. 2018, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, E.M. Leaders against All Odds: Women Victims of Conflict in Colombia. Palgrave Commun. 2016, 2, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mayala, B.K.; Dontamsetti, T.; Croft, T.N. Interpolation of DHS Survey Data at Subnational Administrative Level 2; DHS Spatial Analysis Reports No. 17; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, S.; Suarez, C.M.; Naranjo, C.B.; Báez, L.C.; Rozo, P. The Effects of the Armed Conflict on the Life and Health in Colombia. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2006, 11, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handrahan, L. Conflict, Gender, Ethnicity and Post-Conflict Reconstruction. Secur. Dialogue 2004, 35, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meertens, D.; Stoller, R. Facing Destruction, Rebuilding Life: Gender and the Internally Displaced in Colombia. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2001, 28, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio Pérez, F.E. Forced Displacement among Rural Women in Colombia. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2008, 35, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, C.O.N.; Clark, F.C. (Eds.) Victims, Perpetrators or Actors?: Gender, Armed Conflict and Political Violence; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dollar, D.; Levin, V. The Increasing Selectivity of Foreign Aid, 1984–2003. World Dev. 2006, 34, 2034–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeffler, A.; Outram, V. Need, Merit, or Self-Interest—What Determines the Allocation of Aid? Rev. Dev. Econ. 2011, 15, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzold, C.; Weiler, F. Allocation of Aid for Adaptation to Climate Change: Do Vulnerable Countries Receive More Support? Int. Environ. Agreem. Polit. Law Econ. 2017, 17, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, F.; Klöck, C.; Dornan, M. Vulnerability, Good Governance, or Donor Interests? The Allocation of Aid for Climate Change Adaptation. World Dev. 2018, 104, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raleigh, C. The Search for Safety: The Effects of Conflict, Poverty and Ecological Influences on Migration in the Developing World. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, S82–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B. Interactions between Conflict and Natural Hazards: Swords, Ploughshares, Earthquakes, Floods and Storms. In Facing Global Environmental Change: Environmental, Human, Energy, Food, Health and Water Security Concepts; Brauch, H.G., Spring, Ú.O., Grin, J., Mesjasz, C., Kameri-Mbote, P., Behera, N.C., Chourou, B., Krummenacher, H., Eds.; Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace Book Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 245–256. ISBN 978-3-540-68488-6. [Google Scholar]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Terrestrial Air Temperature and Precipitation: Monthly and Annual Time Series (1950–1999); University of Delaware: Newark, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Felbab-Brown, V. The Coca Connection: Conflict and Drugs in Colombia and Peru. J. Confl. Stud. 2005, 25, 104–128. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist, J.; Kugler, A. Rural Windfall or a New Resource Curse? Coca, Income, and Civil Conflict in Colombia; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; p. w11219. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia, D.; Restrepo, P. Bushes and Bullets: Illegal Cocaine Markets and Violence in Colombia. SSRN Electron. J. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada-Hernández, M.M.; Marín-Jaramillo, M. Cocalero Women and Peace Policies in Colombia. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 89, 103157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brombacher, D.; Westerbarkei, J. From Alternative Development to Sustainable Development: The Role of Development within the Global Drug Control Regime. J. Illicit Econ. Dev. 2019, 1, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceron, C.A.A.; De los Rios-Carmenado, I.; Martín Fernández, S. Illicit Crops Substitution and Rural Prosperity in Armed Conflict Areas: A Conceptual Proposal Based on the Working with People Model in Colombia. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, S.; Adshead, D.; Fay, M.; Hallegatte, S.; Harvey, M.; Meller, H.; O’Regan, N.; Rozenberg, J.; Watkins, G.; Hall, J.W. Infrastructure for Sustainable Development. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIESIN. ITOS Global Roads Open Access Data Set, Version 1 (GROADSv1); NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC): Palisades, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M.; Smith, L. Advances in Using Multitemporal Night-Time Lights Satellite Imagery to Detect, Estimate, and Monitor Socioeconomic Dynamics. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 192, 176–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, C.N.H.; Muller, J.-P.; Elvidge, C.D. Night-Time Imagery as a Tool for Global Mapping of Socioeconomic Parameters and Greenhouse Gas Emissions. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2000, 29, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebener, S.; Murray, C.; Tandon, A.; Elvidge, C.C. From Wealth to Health: Modelling the Distribution of Income per Capita at the Sub-National Level Using Night-Time Light Imagery. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2005, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.V.; Storeygard, A.; Weil, D.N. Measuring Economic Growth from Outer Space. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 994–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, P.C.; Costanza, R. Global Estimates of Market and Non-Market Values Derived from Nighttime Satellite Imagery, Land Cover, and Ecosystem Service Valuation. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, J. Motivation for Bilateral Aid Allocation: Altruism or Trade Benefits. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2008, 24, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mberu, B.U. Internal Migration and Household Living Conditions in Ethiopia. Demogr. Res. 2006, 14, 509–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrotzki, R.J.; Riosmena, F.; Hunter, L.M. Do Rainfall Deficits Predict U.S.-Bound Migration from Rural Mexico? Evidence from the Mexican Census. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2013, 32, 129–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, J.M.; Garfin, D.R.; Espinel, Z.; Araya, R.; Oquendo, M.A.; Wainberg, M.L.; Chaskel, R.; Gaviria, S.L.; Ordóñez, A.E.; Espinola, M.; et al. Internally Displaced “Victims of Armed Conflict” in Colombia: The Trajectory and Trauma Signature of Forced Migration. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2014, 16, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadnes, E.; Horst, C. Responses to Internal Displacement in Columbia: Guided by What Principles? Refuge 2009, 26, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagen, P.W.; Juan, A.F.; Stepputat, F.; Lopez, R.V. Protracted Displacement in Colombia: National and International Responses. In Catching Fire: Containing Forced Migration in a Volatile World; Lexington Lanham: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 73–117. ISBN 978-0-7391-1244-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald, M. Protecting Colombian Refugees in the Andean Region: The Fight against Invisibility. Int. J. Refug. Law 2004, 16, 517–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, V.; Gafaro, M.; Ibáñez, A.M. Forced Migration, Female Labor Force Participation, and Intra-Household Bargaining: Does Conflict Empower Women? Doc. CEDE 2011, 2011, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Gracia, N.; Piras, G.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Hewings, G.J.D. The Journey to Safety: Conflict-Driven Migration Flows in Colombia. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2010, 33, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berents, H. Children, Violence, and Social Exclusion: Negotiation of Everyday Insecurity in a Colombian Barrio. Crit. Stud. Secur. 2015, 3, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Cruz-Ramírez, V.; Medina-Rico, M.; Rincón, C.J. Mental Health in Displaced Children by Armed Conflict-National Mental Health Survey Colombia 2015. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2018, 46, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, P.; Romero, A. Adolescent Girls in Colombia’s Guerrilla: An Exploration into Gender and Trauma Dynamics. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2003, 26, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, L.E. How Conflict and Displacement Fuel Human Trafficking and Abuse of Vulnerable Groups. The Case of Colombia and Opportunities for Real Action and Innovative Solutions. Gron. J. Int. Law 2013, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P. Strengthening Colombian Indicators for Protection in Early Childhood. Int. J. Child. Rights 2015, 23, 638–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.; Mack, E.; Manrique, M. Protecting Young Children from Violence in Colombia: Linking Caregiver Empathy with Community Child Rights Indicators as a Pathway for Peace in Medellin’s Comuna 13. Peace Confl. J. Peace Psychol. 2017, 23, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unit | N | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | |||||||

| All projects | count | 1120 | 0 | 42 | 1.55 | 3.14 | AIMS |

| CP projects | count | 1120 | 0 | 10 | 0.11 | 0.53 | AIMS |

| W projects | count | 1120 | 0 | 3 | 0.09 | 0.3 | AIMS |

| GG projects | count | 1120 | 0 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.32 | DEval |

| Predictor variables | |||||||

| Battle deaths | count | 1120 | 0 | 3688 | 16.85 | 114.44 | UCDP |

| Gender variables | |||||||

| Female head | % | 1118 | 15.74 | 41.01 | 25.82 | 4.22 | IPUMSI |

| Women employed | % | 1118 | 8.1 | 82.55 | 33.64 | 13.61 | IPUMSI |

| Women educated | % | 1118 | 73.99 | 216.09 | 123.01 | 17.58 | IPUMSI |

| Women literate | % | 1118 | 70.53 | 127.8 | 98.74 | 8.67 | IPUMSI |

| Control variables | |||||||

| Administrative performance | index | 1101 | 30.36 | 88.53 | 65.16 | 9.76 | DNP |

| Average precipitation | mm | 1117 | 31.43 | 518.43 | 133.44 | 73.63 | GeoQuery |

| Average temperature | deg. C | 1117 | 8.31 | 31.9 | 22 | 5.44 | GeoQuery |

| Distance to road | km | 1118 | 0.45 | 173.97 | 7.61 | 17.44 | GeoQuery |

| Night-time lights | nanoWatt/cm2/sr | 1120 | 0 | 36.33 | 0.55 | 2.37 | NOAA |

| Coca production | 1/0 | 1120 | 0 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.36 | DRUG |

| Wealth index | scale | 1118 | 1.24 | 8.83 | 5.78 | 1.36 | IPUMSI |

| Conflict migrants | % | 1118 | 0.04 | 14.94 | 1.3 | 1.79 | IPUMSI |

| Young children | count | 1118 | 0.14 | 0.81 | 0.3 | 0.09 | IPUMSI |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Intercept | 0.09 | 0.27 | −1.58 | |||

| Battle deaths | 0.33 | *** | 0.29 | *** | 0.26 | *** |

| Female head a | −0.01 | 0.25 | ||||

| Women employed a | 0.3 | *** | 0.14 | * | ||

| Women educated a | −0.04 | −0.02 | ||||

| Women literate a | −0.05 | −0.08 | ||||

| Administrative performance a | 0.14 | + | ||||

| Average precipitation | 0.06 | |||||

| Average temperature | 0.02 | |||||

| Distance to road | 0.02 | ** | ||||

| Night-time lights | 0.14 | * | ||||

| Coca production | 0.25 | |||||

| Wealth index | 0.02 | |||||

| Conflict migrants a | −0.13 | |||||

| Young children | 1.14 | |||||

| Model statistics | ||||||

| Theta | 2.02 | 2.97 | 3.51 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.49 | |||

| AIC | 3381 | 3251 | 3186 | |||

| N | 1120 | 1118 | 1097 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP Projects | W Projects | GG Projects | ||||

| b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Intercept | −3.35 | −0.63 | −29.09 | *** | ||

| Battle deaths | 0.65 | *** | 0.19 | ** | 0.37 | ** |

| Female head a | 0.3 | −0.14 | 0.04 | |||

| Women employed a | 0.24 | 0.38 | 0.39 | |||

| Women educated a | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.08 | |||

| Women literate a | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.53 | |||

| Administrative performance a | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0.63 | |||

| Average precipitation | 0.17 | −0.95 | 0.91 | + | ||

| Average temperature | 0 | 0.05 | −0.05 | |||

| Distance to road | 0.05 | * | 0.1 | 0.02 | ||

| Night-time lights | 0.41 | * | 0.15 | 0.21 | + | |

| Coca production | −0.14 | −1.65 | −0.25 | |||

| Wealth index | −0.16 | −0.8 | ** | −0.58 | ||

| Conflict migrants a | 0.33 | −3.97 | + | 0.04 | ||

| Young children | 4 | + | −3.13 | −2.45 | ||

| Model statistics | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.36 | 0.55 | 0.5 | |||

| AIC | 478 | 377 | 305 | |||

| N | 1097 | 1097 | 1097 | |||

| All Projects | CP Projects | W Projects | GG Projects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Battle deaths | 0.25 | *** | 0.65 | *** | 0.08 | 0.38 | ** | |

| Female head a | 0.17 | 0.29 | −0.48 | −0.16 | ||||

| Battle deaths × Female head | 0.13 | ** | 0.01 | 0.61 | *** | 0.27 | ||

| Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |||||

| b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Battle deaths | 0.22 | *** | 0.66 | *** | 0.15 | + | 0.3 | + |

| Women employed a | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.29 | ||||

| Battle deaths × Women employed | 0.1 | *** | −0.02 | 0.47 | *** | 0.2 | + | |

| Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | |||||

| b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Battle deaths | 0.26 | *** | 0.64 | *** | 0.21 | ** | 0.36 | ** |

| Women educated a | −0.01 | 0 | 0.2 | + | 0.02 | |||

| Battle deaths × Women educated | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.1 | ||||

| Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | Model 16 | |||||

| b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | b | sig. | |

| Battle deaths | 0.24 | *** | 0.64 | *** | 0.09 | 0.36 | * | |

| Women literate a | −0.09 | −0.22 | −0.07 | 0.41 | ||||

| Battle deaths × Women literate | 0.12 | *** | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.16 | + | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nawrotzki, R.J.; Gantner, V.; Balzer, J.; Wencker, T.; Brüntrup-Seidemann, S. Strategic Allocation of Development Projects in Post-Conflict Regions: A Gender Perspective for Colombia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042304

Nawrotzki RJ, Gantner V, Balzer J, Wencker T, Brüntrup-Seidemann S. Strategic Allocation of Development Projects in Post-Conflict Regions: A Gender Perspective for Colombia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042304

Chicago/Turabian StyleNawrotzki, Raphael J., Verena Gantner, Jana Balzer, Thomas Wencker, and Sabine Brüntrup-Seidemann. 2022. "Strategic Allocation of Development Projects in Post-Conflict Regions: A Gender Perspective for Colombia" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042304

APA StyleNawrotzki, R. J., Gantner, V., Balzer, J., Wencker, T., & Brüntrup-Seidemann, S. (2022). Strategic Allocation of Development Projects in Post-Conflict Regions: A Gender Perspective for Colombia. Sustainability, 14(4), 2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042304