Principles of Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Decision-Making for Behavioral Development Economics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

3. Review Key-Points, Literature and History

3.1. The Nudge Theory: The Behavioral Development Economics Approach

3.2. Nudge versus Boost: Retrospect and Prospect

3.2.1. The Boost Theory: The Economic Point of View

3.2.2. The Boost Theory: The Psychological Point of View

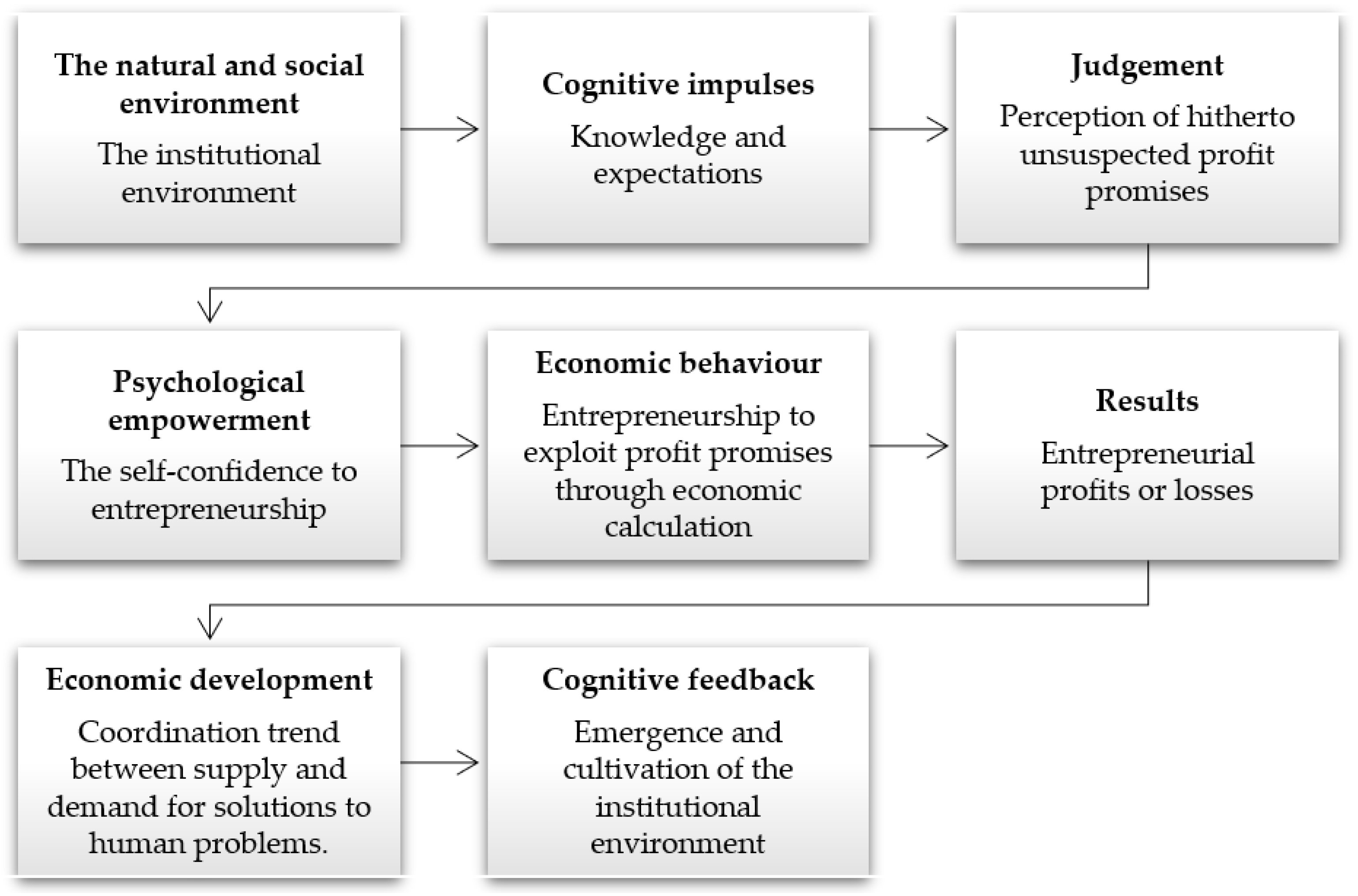

3.2.3. Empowering Economic Development

3.3. Steering or Empowering Decision-Making

4. Discussion and Proposals

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Libertarian paternalism. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, D.M.; Welch, B. Debate: To nudge or not to nudge. J. Political Philos. 2010, 18, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, P.G. The definition of nudge and libertarian paternalism: Does the hand fit the glove? Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2016, 7, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trout, J.D. Paternalism and cognitive bias. Law Philos. 2005, 24, 393–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A. Mind the gap: The effectiveness of incentives to boost retirement saving in Europe. OECD Econ. Stud. 2004, 39, 111–144. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Factsheet No. 311. Geneva, Switzerland. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 26 October 2021).

- Kahneman, D.; Slovic, P.; Tversky, A. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Demeritt, A.; Hoff, K. The making of behavioral development economics. Hist. Political Econ. 2018, 50, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, M.; Rao, G.; Schilbach, F. Behavioral development economics. In Handbook of Behavioral Economics: Applications and Foundations 1; Douglas Bernheim, B., DellaVigna, S., Laibson, D., Eds.; North-Holland: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 345–458. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 1449–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. J. Risk Uncertain. 1992, 5, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E. The economist as plumber. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teal, J.; Kusev, P.; Heilman, R.; Martin, R.; Passanisi, A.; Pace, U. Problem Gambling ‘Fuelled on the Fly’. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.; Kusev, P.; Teal, J.; Baranova, V.; Rigal, B. Moral Decision Making: From Bentham to Veil of Ignorance via Perspective Taking Accessibility. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusev, P.; Van Schaik, P.; Martin, R.; Hall, L.; Johansson, P. Preference reversals during risk elicitation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2020, 149, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusev, P.; van Schaik, P.; Ayton, P.; Dent, J.; Chater, N. Exaggerated risk: Prospect theory and probability weighting in risky choice. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2009, 35, 1487–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huerta de Soto, J. The Austrian School: Market Order and Entrepreneurial Creativity; Edward Elgar: Northhampton, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mises, L. Human Action: A Treatise on Economics; Henry Regnery: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Alonso Neira, M.A.; Huerta de Soto, J. Principles of sustainable economic growth and development: A call to action in a post-COVID-19 world. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.I. Principios Modernos de Economía del Desarrollo: Teoría y Práctica; Unión Editorial: Madrid, Spain, In press.

- Moyo, D. Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa; The Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Easterly, W. The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators, and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Backhouse, R.; Medema, S. On the definition of economics. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirowski, P.E. Physics and the marginalist revolution. Camb. J. Econ. 1984, 8, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, P.E. More Heat than Light: Economics as Social Physics, Physics as Nature’s Economics; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowski, P.E. The when, the how and the why of mathematical expression in the history of economic analysis. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Persky, J. The ethology of homo economicus. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, T.; Li, Y.; Takagishi, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kiyonari, T. In search of Homo economicus. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1699–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhouse, R.E. An empirical philosophy of economic theory. British J. Philos. Sci. 1995, 46, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P.J.; Lopez, E.J. Austrian economics and public choice. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2002, 15, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alacevich, J. The Birth of Development Economics: Theories and Institutions. Hist. Political Econ. 2018, 50, 114–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, M. Carl Menger and Homo Oeconomicus: Some thoughts on Austrian theory and methodology. J. Econ. Issues 1982, 16, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H. From homo economicus to homo sapiens. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Subjective probability: A judgment of representativeness. Cogn. Psychol. 1972, 3, 430–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, K.; Joseph, E. Stiglitz. Equilibrium fictions. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, K.; Joseph, E. Stiglitz. Striving for balance in economics: Towards a theory of the social determination of behavior. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2016, 126, 25–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heukelom, F. Behavioral Economics: A History; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H. Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Development Economics; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.B. Economics imperialism under the impact of psychology: The case of behavioral development economics. OEconomia 2013, 3, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Mullainathan, S. Behavioral design: A new approach to development policy. Rev. Income Wealth 2014, 60, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.K.; Zhao, J.; Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E. Money in the mental lives of the poor. Soc. Cogn. 2018, 36, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharif, M.A.; Mogilner, C.; Hershfield, H.E. Having too little or too much time is linked to lower subjective well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 121, 933–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.S.H.; Xinping, X.; Khan, M.A.; Harjan, S.A. Investor and manager overconfidence bias and firm value: Micro-level evidence from the Pakistan equity market. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2018, 8, 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.S.H.; Khan, M.A.; Meyer, N.; Meyer, D.F.; Oláh, J. Does herding bias drive the firm value? Evidence from the Chinese equity market. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, R.; Yang, X.; Li, N.; Khan, M.A. Herd behavior in venture capital market: Evidence from China. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.T.; Engelen, B. The ethics of nudging: An overview. Philos. Compass 2020, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.H., Jr. Cognitive biases and their impact on strategic planning. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benartzi, S.; Beshears, J.; Milkman, K.L.; Sunstein, C.R.; Thaler, R.H.; Shankar, M.; Galing, S. Should governments invest more in nudging? Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sunstein, C. Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, S.; Kirman, A.; Sethi, R. Retrospectives: Friedrich Hayek and the market algorithm. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devereaux, A.N. The nudge wars: A modern socialist calculation debate. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2019, 32, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, T.M. Nudging and manipulation. Political Stud. 2013, 61, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, S. Behavioural economics: A virginia political economy perspective. Econ. Aff. 2016, 36, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasic, S. Are Regulators Rational? J. Des Econ. Et Des Etudes Hum. 2011, 17, Article 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F.A. The use of knowledge in society. Am. Econ. Rev. 1945, 35, 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Kirzner, I.M. The entrepreneurial market process—An exposition. South. Econ. J. 2017, 83, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta de Soto, J. The Theory of Dynamic Efficiency; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G. Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment: A New Approach to the Firm; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G.; Lien, L.B.; Zellweger, T.; Zenger, T. Ownership competence. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 302–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, G.R. Hayek’s sensory order. Theory Psychol. 2002, 12, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. Emergent properties in the work of Friedrich Hayek. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 82, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.A. Property rights, entrepreneurship and coordination. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2013, 88, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redford, A. Property rights, entrepreneurship, and economic development. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2020, 33, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirzner, I.M. Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: An Austrian approach. J. Econ. Lit. 1997, 35, 60–85. [Google Scholar]

- Boettke, P.J. Entrepreneurship, and the entrepreneurial market process: Israel M. Kirzner and the two levels of analysis in spontaneous order studies. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2014, 27, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piano, E.E.; Rouanet, L. Economic calculation and the organization of markets. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2020, 33, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, J.B. On the complexities of complex economic dynamics. J. Econ. Perspect. 1999, 13, 169–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosser, J.B., Jr. Emergence and complexity in Austrian economics. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 81, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinhocker, E.; Hanauer, N. Redefining capitalism. McKinsey Q. 2014, 3, 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Wang, W.H.; Zhu, H. Israel Kirzner on dynamic efficiency and economic development. Procesos De Merc. 2020, 17, 283–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P.J.; Coyne, C.J. Entrepreneurship and development: Cause or consequence? Adv. Austrian Econ. 2003, 6, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N. How strategic entrepreneurship and the institutional context drive economic growth. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2013, 7, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Foss, N.J. Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: What do we know and what do we still need to know? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 30, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rothbard, M.N. Power and Market: Government and the Economy; Sheed Andrews and McMeel: Kansas City, KS, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, V.I. Salvador Allende’s development policy: Lessons after 50 years. Econ. Aff. 2021, 41, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.I. Ciberplanificación, propiedad privada y cálculo económico. Rev. De Econ. Inst. 2021, 23, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Espinosa, V.I.; Peña-Ramos, J.A. Private Property Rights, Dynamic Efficiency and Economic Development: An Austrian Reply to Neo-Marxist Scholars Nieto and Mateo on Cyber-Communism and Market Process. Economies 2021, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta de Soto, J. Socialism, Economic Calculation and Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.T. From Subsistence to Exchange and Other Essays; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 483–504. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D.A. Foundations of Entrepreneurship and Economic Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aimar, T. The curious destiny of a heterodoxy: The Austrian economic tradition. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2009, 22, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimar, T. The Economics of Ignorance and Coordination: Subjectivism and the Austrian School of Economics; Edward Elgar: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, G.; Borgia, D.; Schoenfeld, J. The motivation to become an entrepreneur. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2005, 11, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gadon, L.; Johnstone, L.; Cooke, D. Situational variables and institutional violence: A systematic review of the literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 515–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S. Dynamics of interventionism. In Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics; Boettke, P.J., Coyne, C.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Frese, M.; Gielnik, M.M. The psychology of entrepreneurship. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cropley, D.H.; Cropley, A.J. The Psychology of Innovation in Organizations; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgievski, M.J.; Stephan, U. Advancing the psychology of entrepreneurship: A review of the psychological literature and an introduction. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 65, 437–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, C.M. La Teoria Evolutiva de las Instituciones: La Perspectiva Austriaca; Unidad Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boettke, P.; Subrick, J.R. Rule of law, development, and human capabilities. Supreme Court Econ. Rev. 2003, 10, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwartney, J.D.; Holcombe, R.G.; Lawson, R.A. Economic freedom, institutional quality, and cross-country differences in income and growth. Cato J. 2003, 24, 205–233. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Foa, R.; Peterson, C.; Welzel, C. Development, freedom, and rising happiness: A global perspective (1981–2007). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 3, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, J.; Gwartney, J.D.; Montesinos, H.M. The transportation-communication revolution: 50 years of dramatic change in economic development. Cato J. 2020, 40, 153–198. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.H.; Moreno-Casas, V.; Huerta de Soto, J. A free-market environmentalist transition toward renewable energy: The cases of Germany, Denmark, and the United Kingdom. Energies 2021, 14, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.J.; Whitman, G. Escaping Paternalism: Rationality, Behavioral Economics, and Public Policy; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Carreiro, Ó.R. Old and new development economics: A reassessment of objectives. Q. J. Austrian Econ. 2021, 24, 254–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V. Epistemological problems of development economics. Procesos De Merc. 2020, 17, 55–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwig, R.; Ryall, M.D. Nudge versus boost: Agency dynamics under libertarian paternalism. Econ. J. 2020, 130, 1384–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnellenbach, J. A constitutional economics perspective on soft paternalism. Kyklos 2016, 69, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, R.N. Knowledge and rationality in the Austrian school: An analytical survey. East. Econ. J. 1985, 11, 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, M.J. The problem of rationality: Austrian economics between classical behaviorism and behavioral economics. In Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics; Boettke, P.J., Coyne, C.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jolls, C.; Sunstein, C.R.; Thaler, R. A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stanf. Law Rev. 1997, 50, 1471–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R. Deciding by default. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 2013, 162, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, T.M. Counter-Manipulation and Health Promotion. Public Health Ethics 2017, 10, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guala, F.; Mittone, L. A political justification of nudging. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2015, 6, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halpern, D.; Sanders, M. Nudging by government: Progress, impact, & lessons learned. Behav. Sci. Policy 2016, 2, 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, O.P.; Gino, F.; Norton, M.I. Budging beliefs, nudging behaviour. Mind Soc. 2018, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayek, F.A. The Sensory Order: An Inquiry into the Foundations of Theoretical Psychology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, B. Some reflections on F. A. Hayek’s the sensory order. J. Bioeconomics 2004, 6, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, J.M. Hayek in today’s cognitive neuroscience. Adv. Austrian Econ. 2011, 15, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- McQuade, T.J.; Butos, W.N. The sensory order and other adaptive classifying systems. J. Bioeconomics 2005, 7, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta de Soto, J.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Bagus, P. Principles of monetary & financial sustainability and wellbeing in a post-COVID-19 world: The crisis and its management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagus, P.; Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. COVID-19 and the political economy of mass hysteria. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panorama Social de América Latina 2020. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/46687-panorama-social-america-latina-2020 (accessed on 13 November 2021).

- Rizzo, M.J.; Whitman, D.G. The knowledge problem of new paternalism. Brigh. Young Univ. Law Rev. 2009, 2009, 905–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rizzo, M.J.; Whitman, D.G. Little brother is watching you: New paternalism on the slippery slopes. Ariz. Law Rev. 2009, 51, 685–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, G.P., Jr.; Rizzo, M. Austrian Economics Re-examined: The Economics of Time and Ignorance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, P. The economics of ignorance or ignorance of economics? Crit. Rev. 1989, 3, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsmann, J.G. Economic science and neoclassicism. Q. J. Austrian Econ. 1999, 2, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.H. The long-run effect of government ideology on economic freedom. Econ. Aff. 2019, 39, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kimm Gnangnon, S. Economic complexity and poverty in developing countries. Econ. Aff. 2021, 41, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carden, A.; Hall, J. Why are some places rich while others are poor? The institutional necessity of economic freedom. Econ. Aff. 2010, 30, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shand, A. The Failure of ‘Market Failure’. Econ. Aff. 1987, 7, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, P. Market failure: A failed paradigm. Econ. Aff. 2008, 28, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachanosky, I. En defensa del monopolio competitivo. Procesos De Merc. 2020, 17, 233–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, V.I.; Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Recuero-López, F. The political economy of rent-seeking: Evidence from spain’s support policies for renewable energy. Energies 2021, 14, 4197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P.J.; Candela, R.A. The liberty of progress: Increasing returns, institutions, and entrepreneurship. Soc. Philos. Policy 2017, 34, 136–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Rents and economic development: The perspective of Why Nations Fail. Public Choice 2019, 181, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Naidu, S.; Restrepo, P.; Robinson, J.A. Democracy does cause growth. J. Political Econ. 2019, 127, 47–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamerlin, S.C.; Kasson, P.M. Managing Coronavirus Disease 2019 spread with voluntary public health measures: Sweden as a case study for pandemic control. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 3174–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähler, M.T. How Behavioral Economics can enrich the Perspective of the Austrian School. Procesos De Merc. 2018, 15, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F.A. The fatal conceit: The errors of socialism. In The Collected Works of Friedrich August Hayek; Bartley, W.W., III, Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

| Key Points | Steering Criteria | Empowering Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive biases in decision -making psychology | Decision-making psychology can produce suboptimal outcomes because people can be irrational, quasi-rational, or possess limited rationality due to systematic cognitive biases in the economic way of thinking. Any deviation from what paternalists denominate “true” judgments lacks rationality or some cognitive bias. | The paternalistic ideal is paradoxical. The political decision-makers are themselves people and, therefore, have cognitive biases! If they recognize that they too have cognitive biases, their whole model will crumble. Steering an architecture of choices to approximate people’s ‘true’ judgments implies intellectual naivety, dictatorial arrogance, or both. |

| The role of the institutional environment in political decision-making | The steering criteria neglect the comparative perspective of the institutional environment to cultivate economic development. Paternalists usually focus their research on designing coercive state interventions to steer people’s decision-making through default rules. | The empowering criteria place the comparative perspective of the institutional environment as essential for economic development. There is a big difference between, on the one hand, a competitive market process with low confiscation risks and, on the other hand, a market intervened by the confiscation policy. |

| The role of freedom in behavioral development economics | The steering criteria do not consider how judgments construction on the fly works. If cognitive biases can be enough to justify coercive state interventionism for people’s good, behavioral economists have not adequately addressed how the mind works. | Judgments emerge on the fly as a process of increasing classification that generates phenomenological experience, expectations, and learning by seeing and doing. Like two snowflakes, no two individuals are identical. Each person’s mental storage of classification is subjected to a continuous gradual change according to their judgments under uncertainty. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Espinosa, V.I.; Wang, W.H.; Huerta de Soto, J. Principles of Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Decision-Making for Behavioral Development Economics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042145

Espinosa VI, Wang WH, Huerta de Soto J. Principles of Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Decision-Making for Behavioral Development Economics. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042145

Chicago/Turabian StyleEspinosa, Victor I., William Hongsong Wang, and Jesús Huerta de Soto. 2022. "Principles of Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Decision-Making for Behavioral Development Economics" Sustainability 14, no. 4: 2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042145

APA StyleEspinosa, V. I., Wang, W. H., & Huerta de Soto, J. (2022). Principles of Nudging and Boosting: Steering or Empowering Decision-Making for Behavioral Development Economics. Sustainability, 14(4), 2145. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042145