1. Introduction

In Slovenia, there is a rich history of horse breeding as the country already had quality horse breeds in the 15th century, such as the “Kras” horse, which was later crossed with other breeds [

1]. Traditional breeds are those that do not originate from the Republic of Slovenia, or their origin have not been proven. In this study, trotting horses, the Ljutomer Trotter and the Haflinger, are presented as traditional breeds. Indigenous breeds are those for which it has been proven, on the basis of historical sources, that they originated from the Republic of Slovenia, or, in other words, the Republic of Slovenia was the original environment for the development of the breeds. The indigenous breeds discussed here are the Lipizzaner horse, the Slovenian Cold-Blooded horse, the Posavec horse and the Bosnian Mountain horse. Nowadays, the choice of breed is quite important, and it is difficult to make a decision that optimises riding, economic and breeding benefits. The present study is important because the population of traditional and indigenous horse breeds is shrinking. We expect that the study results can be used to aid conservation decision makers in improving traditional and indigenous horse breeding plans. This can help Slovenian horse breeds be considered more attractive, and ideally, their populations will be preserved. Today, the value of indigenous breeds—from genetic conservation to socioeconomic and cultural heritage viewpoints—is fairly well-known (e.g., [

2]). Despite the numerous values of farm animal breeds (e.g., sustainability and culture), economic value is often prioritised over socioeconomic importance or cultural heritage [

3,

4].

There are many different breed options and crossbreeds with unique characteristics. The aim of this study was to examine if the DEX (Decision Expert) method is appropriate for the assessment of different horse breeds and if the method gives clear directions regarding what can be recognised as important assets in the purchasing process. The aim of this research is to fill the gap in research studies where authors apply the multi-criteria decision modelling approach to horse breeding. Because the multi-criteria evaluation of horse breeds is a new methodological approach, the criteria have not yet been specified. Thus, the novel academic aspect of this paper is that it specifies the criteria that are important for riders and horse breeders. Lastly, the results give clear indications of where the threats and opportunities exist for breeding traditional and indigenous horses. The group of experts who contributed to this work are of different professions working under the Institute of Economic and Breeding Technology of Sport Horses, established by the University of Maribor, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

In the assessment research field, multi-criteria decision analysis (also known as MCDA) is often employed as an ex-ante evaluation tool for the examination of alternative projects or strategic solutions [

5]. The method has been applied to numerous real-life decision and evaluation problems in agriculture [

6,

7,

8], rural development and environmental protection [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Decision making is a process that accompanies us through everyday life and in a kind of sequence, in which we have to choose between a given version or the possibility of choosing what, in certain conditions, best suits the set goals or criteria. In some cases, we want to evaluate the variants—to classify them from the best to the worst [

14]. This methodology, also known as DEX methodology, is suitable to assess horse breeds. The DEX method is often used in the multi-criteria decision analysis. It begins with the creation of a collection with the help of software tools for modelling preferential knowledge for multiparameter decision making. In 1988, the DEX method was developed in cooperation with the Faculty of Organisational Sciences of the University of Maribor and the Jožef Štefan Institute in Ljubljana. Eventually, researchers became familiar with the topic of the computer program DEXi itself, which was developed with the help of the Ministry of Education and Sports in 1999; it is based on the DEX methodology and operates in a developed environment. An important aspect of the program is its open-access online version, which can be used anytime, anywhere and by anyone.

The paper is organized into four sections. First, the study area and data sources are defined; this is followed by a description of the methodology and development process. Next, the application of the assessment tool is demonstrated and discussed. The paper concludes with our main findings, recognising some limitations of the approach used and giving recommendations for further research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Model Development Process

2.1.1. Data Sources

Based on the input data, in order to capture the influence of several horse breed factors simultaneously, we developed a multi-criteria decision model for the evaluation of traditional and indigenous horse breeds. We defined the main criteria or attributes as follows: (i) appearance/temperament/training, (ii) cost/use and (iii) environmental adaptation.

Traditional breeds are those that do not originate from the Republic of Slovenia, or their origins have not been proven. Two trotting horses, the Ljutomer Trotter and the Haflinger, are considered for this survey’s purpose. These breeds have been continuously bred in the Republic of Slovenia for 30 to 50 years. There is Slovenian breeding documentation for the breeds, showing that the breeds have been kept for at least five generations, and breeding plans are performed for them.

Indigenous breeds are those that, based on historical sources, have been proven to originate from the Republic of Slovenia, or, in other words, the Republic of Slovenia was the original environment for breed development, and Slovenian breeding documentation for them exists. These breeds have origins dating back at least five generations. In this survey, the Lipizzaner horse, Slovenian Cold-Blooded horse, Posavina horse and Bosnian Mountain horse were considered.

The data were collected from national breeding plans for the horse breeds that are assessed in this survey. The national breeding plans are confirmed by veterinarians, agricultural and political actors, and they are reviewed every 5 to 10 years. For clarity throughout the paper, we denoted our developed model as the HORQUAL model.

2.1.2. Criteria Identification

For the research task, we determined the following basic criteria: horse exterior, temperament, intrinsic value, skills/abilities and adaptability to the environment. Based on these basic criteria, we determined the second-level criteria. The process can go further and further until the decision maker or assessor meets their individual needs. We refer to the distribution of criteria as a tree of criteria or an attribute tree. Some authors [

15,

16] state that an attribute tree can have one or more criteria among the main attributes, and each main attribute can include several subattributes. In

Figure 1, the criteria are presented as an attribute tree with short explanations of the attributes listed.

In our research, the hierarchical attribute tree was structured with the aggregate attributes on the higher level, followed by the aggregate subattributes on the lower level. The hierarchy of the HORQUAL model (attributes and utility functions) is based on a preliminary literature review of breeding plans and indicators of performance for horses. The aggregation process is based on the utility functions. In the DEX program, the utility functions are represented by decision rules, which are acquired from the researchers (more details in the next subsection).

The second step of the HORQUAL model development was based on a value scale definition for each attribute and subattribute (

Figure 2). The value scale is discrete and typically consists of words [

18]. According to scale values, decision makers can choose one option for each attribute to assess the individual characteristics of the horses.

2.2. Definition of Utility Function

The next step was to define the decision rules (i.e., utility functions—UF). The aggregation process is based on the utility functions. In the DEX program, the utility functions are represented by decision rules, which are acquired from the literature [

8]. The decision rules describe the value of an aggregate attribute for each combination of input attributes and express the relative importance of individual attributes [

19]. The relative importance of an individual attribute is represented by the weight value. Setting the weights (approx. 33%) defines the relationship between “Exterior”, “Temperament” and “Schooling” attributes since they have a similar impact on the final assessment [

20], as shown in

Figure 3.

The authors assumed that the relative importance of “Exterior”, “Temperament” and “Schooling” attributes were balanced in the determination process of the final assessment. In the survey, the weights should be 33.33% for all attributes; the reason for a potential imbalance lies in the normalisation process, which is automatically performed by the DEX programme. This occurs because some attribute scales can have more values than others [

21].

The first and last decision rules were strictly defined by the experts. For example, if the assessment of “Exterior” is

inappropriate, “Temperament” is

not susceptible and “Schooling” is

less than less appropriate, the assessment of the “Horse Exterior/Temperament/Training” is

unacceptable (

Figure 4). Some decision rules are expressed in a more complex form, such as “≥”, which means

equal or better. Decision rules were defined for all aggregate attributes of the hierarchy; thus, the final sum gives 38 utility functions.

3. Results and Discussion

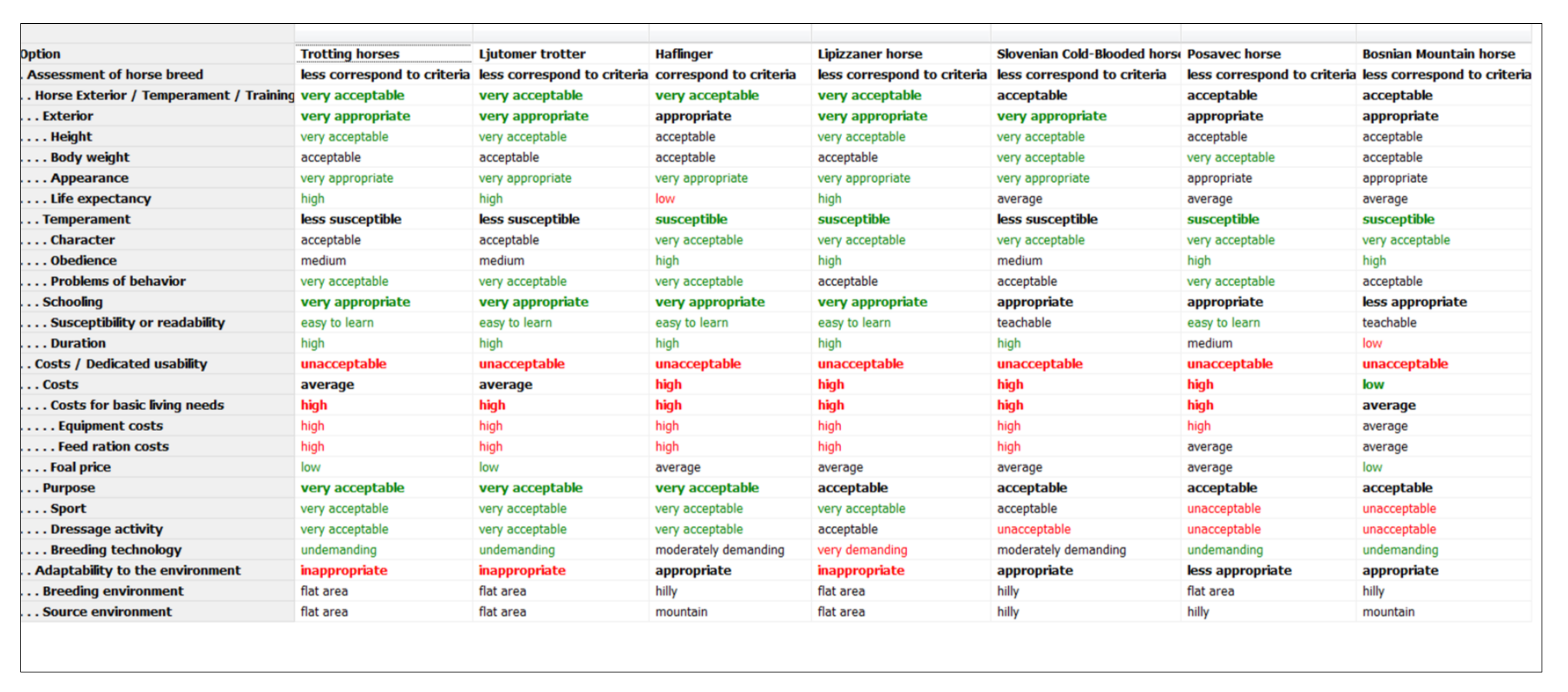

The qualitative discrete criteria used in the DEXi program are values described in words, so it is not possible to use numerical values, and the numerical values of qualitative events must be used instead. Based on the obtained results of the evaluation of all seven selected traditional and indigenous horse breeds, the final evaluation of individual horses can be seen as well as the evaluation of the main criteria and subcriteria (

Figure 5).

Figure 5 demonstrates that only one variant (the Haflinger horse) was estimated as “

corresponds to criteria” while the others received the worst possible assessment (“

less correspondence with the criteria”). The Haflinger horse received a medium assessment in two of three subattributes on the first level (“

Adaptability to the environment” and “Horse Exterior/Temperament/Training”). According to the utility function represented in

Section 2.2, the final assessment of this type of horse is higher compared to the others. These results are suitable but not enough to identify possibilities for the improvement of the results. This is important and can help decision makers (in this case, veterinarians, breeders, riders and others) understand how to improve breeding plans and give them clear benchmarks. The DEX methodology offers this opportunity in creating the Plus-minus-1 analyses, which we present in some depth in the next subsection.

Common to all assessed horse breeds is the unfavourable assessment of costs, which were assessed as unacceptable due to high costs for equipment and feed. The breeds with a favourable “Horse Exterior” assessment are appropriate for sport purposes. Particularly, the Ljutomer Trotter, Haflinger and Lipizzaner horses are well suited for sport purposes and dressage or trotting discipline. An important factor in a higher final assessment is the subcriterion “Adaptability to the environment”. In this regard, only the Haflinger horse had an appropriate assessment. The “Horse/Temperament/Training” is the most important final assessment.

Plus-Minus-1 Analysis (PS-1)

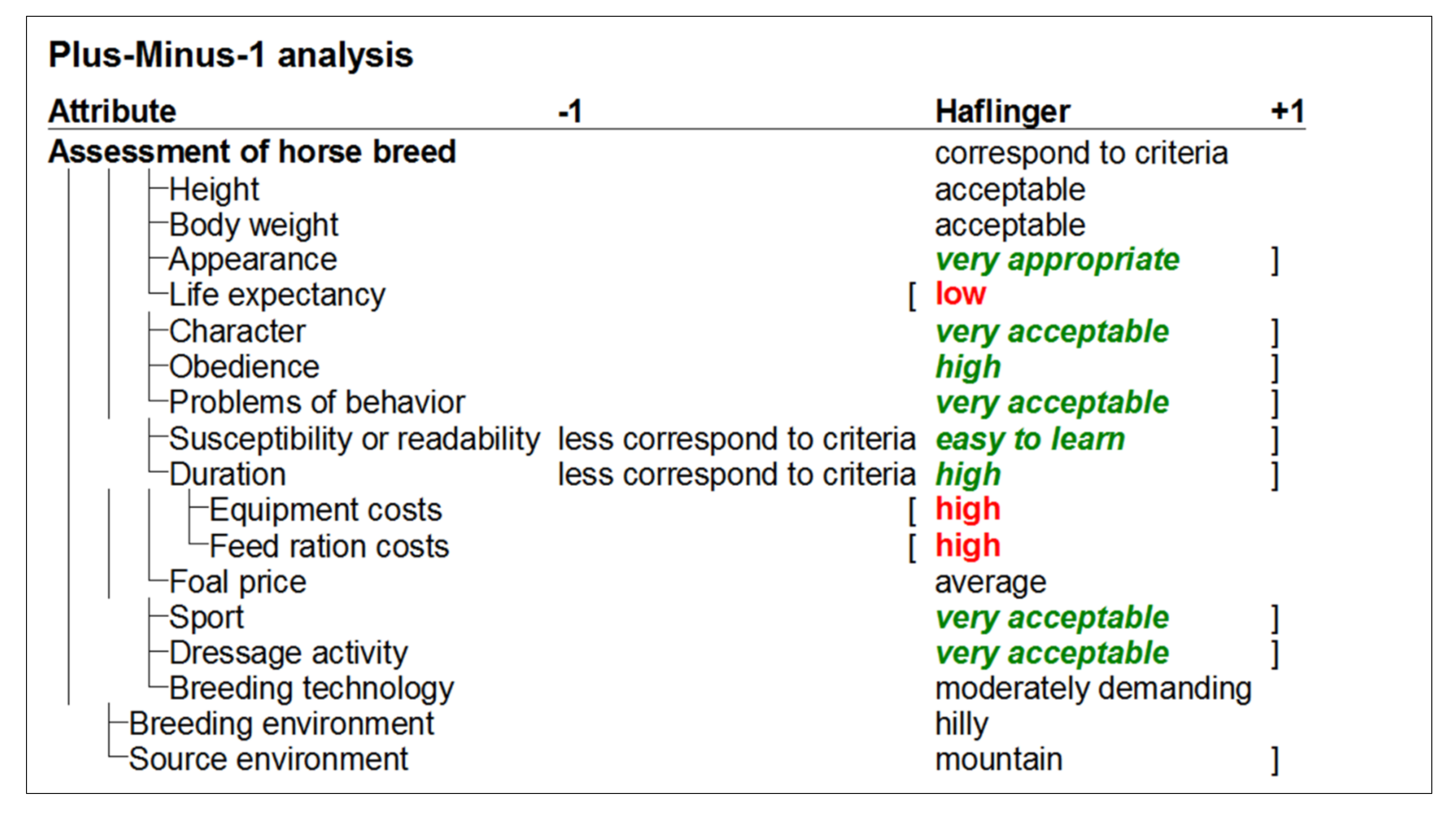

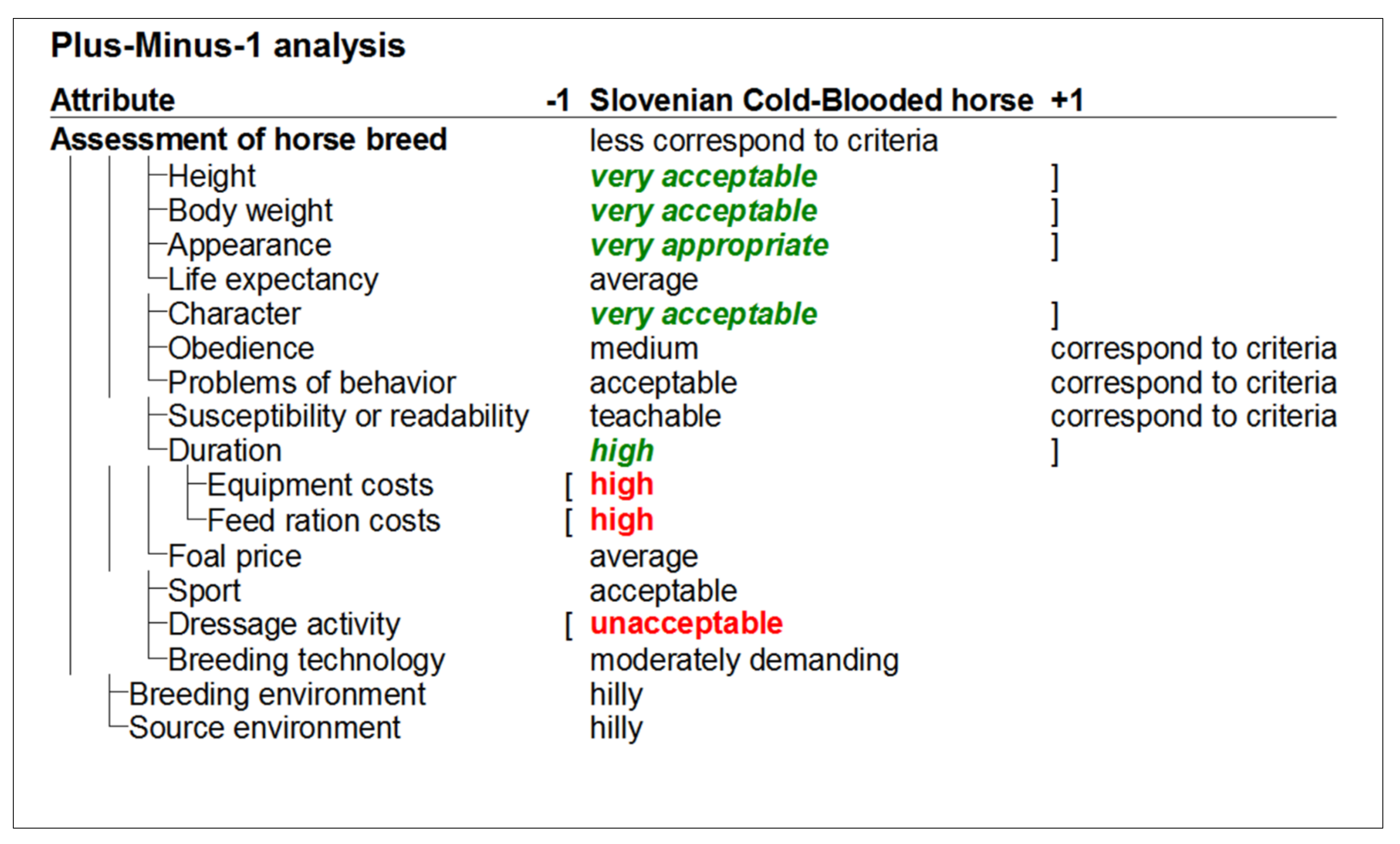

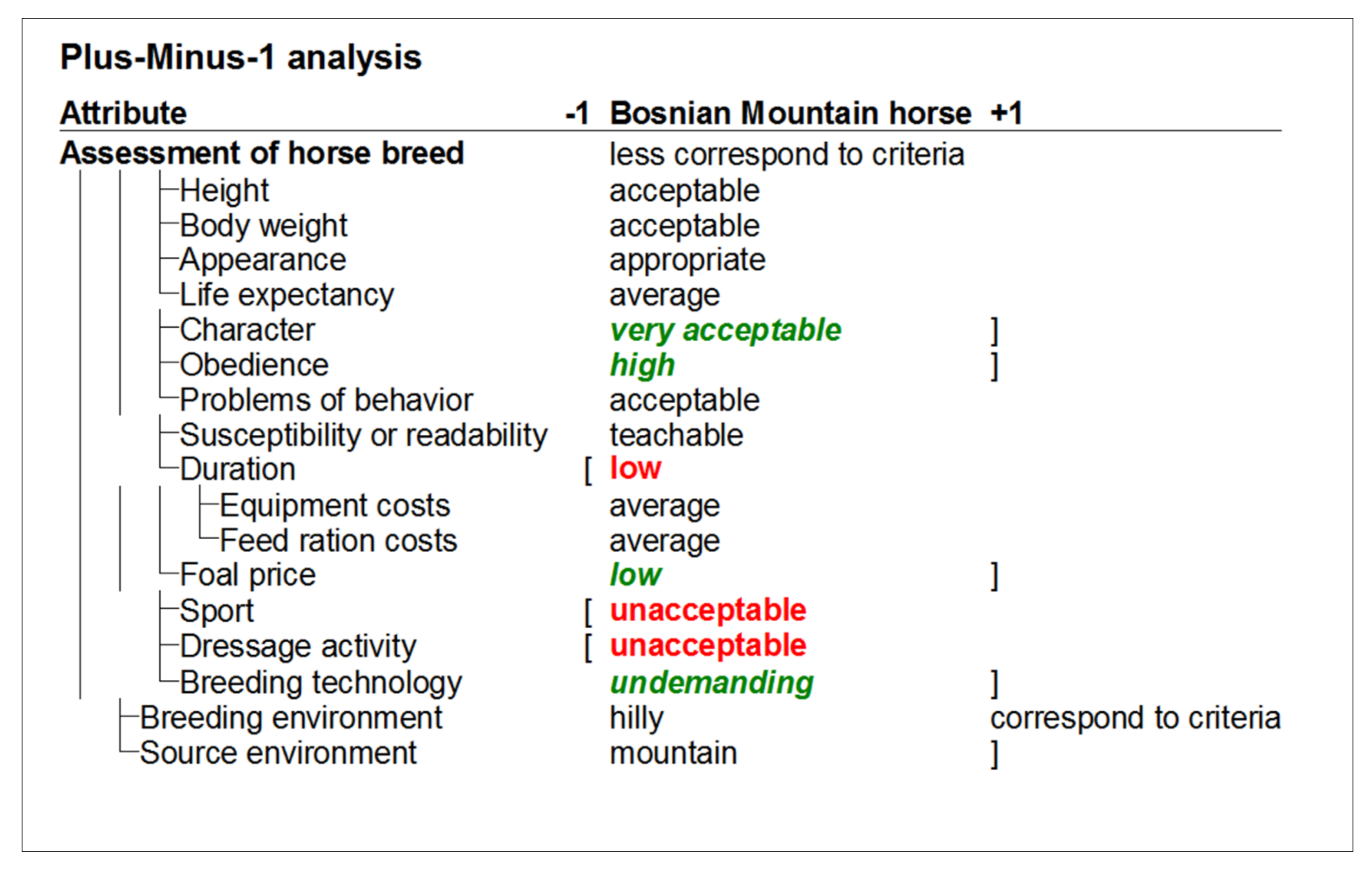

A PS-1 analysis describes changes in certain basic attributes, by one degree upwards or downwards (if possible), that are independent of other attributes [

8]. In

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, the results of the PS-1 for the three types of horse breeds are presented.

Only three types of horses (Haflinger horse, Slovenian Cold-Blooded horse and Bosnian Mountain horse) have “opportunities” and “threats” to improve or to impair their final assessment. For example, if the attributes “Obedience”, “Problems of behaviour”, “Susceptibility or readability” and “Breeding environment” will improve by one degree and other attributes stay at the same level, the final assessment of the Slovenian Cold-Blooded horse and the Bosnian Mountain horse will improve from “less correspondence with the criteria” to “corresponds to the criteria”. It can be seen in the case of the Haflinger horse that the attributes “Susceptibility or readability” and “Duration” represent the threats. If the assessment of one of these attributes falls by one degree, the final assessment will worsen from “corresponds to the criteria” to “less correspondence with the criteria”.

From the PS-1 analysis, it can be seen that the Bosnian Mountain horse and the Slovenian Cold-Blooded horse have opportunities for improving their final assessment while in the case of the Haflinger horse, there are two threats that can impair the final assessment. These data are useful for experts who devise breeding plans as they emphasize which breeds and attributes to focus on.

4. Conclusions

With the HORQUAL model, it is easy and effective to choose the most suitable horse breeds for certain purposes since the breeds and their attributes can be analysed and compared with each other as well as to choose between traditional and indigenous breeds of horses. We adapted the HORQUAL model to each individual breed as they differ in terms of lifestyle, expectations, requirements and experience. In this way, decision makers will be able to decide on appropriate breeds for specific purposes more easily and reliably. The DEX methodology can help examine the traits of the given breeds and compare their characteristics. Additionally, the results of the PS-1 clearly state the opportunities for breeding improvements.

The final evaluation of the breed choice is influenced by a number of composite criteria with corresponding subcriteria and their value stocks. We recognise some limitations of the study, which lie in the transformation process of numerical (quantitative) to descriptive (qualitative) attributes.

The crucial aim of the study was to evaluate native horse breeds from Slovenia, according to criteria related to breeding plans and the individual attributes of horse breeds to give a final assessment of how indigenous and traditional horse breeds are suitable for wider use. Additionally, with the PS-1 analysis, we identified possibilities for improving the horses’ characteristics. According to these statements, some criteria (such as exterior, temperament, training performance and adaptability to the environment) were recognised as relevant. Other criteria (costs and purpose) pertain to the individual assessment of the horses carried out by decision makers. However, with a combination of both, the HORQUAL model is a user-friendly decision tool that gives decision makers the option to weigh their individual needs in the final decision/assessment. Due to the relatively easy applicability of the DEX methodology, the decision maker can change (add or remove criteria) and adapt the model to specific conditions.

This process can be enhanced with some expertise to handle the hierarchical assessment defining the weights of attributes. The application of the HORQUAL model in this research area is relatively new, and it proved to be a useful decision support tool here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.P. and Č.R.; methodology, N.F., J.P. and Č.R.; software, N.F.; validation, J.P., N.F. and Č.R.; formal analysis, N.F., J.P. and Č.R.; investigation, N.F.; resources, N.F. and J.P.; data curation, N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., N.F., Č.R., K.P. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.T.; supervision, Č.R. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This reserach received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harris, M.; Swinney, N.J. Konji: Izvor in Značilnosti 100 Pasem z Vsega Sveta. Horses: Origin and Characteristics of 100 Breeds from All Over The World; Metro Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011; 240p. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn, R. The challenge of conserving indigenous domesticated animals. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 45, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Goldman, M.J. Beyond payments for ecosystem services: Considerations of trust, livelihoods and tenure security in community-based conservation projects. Oryx 2017, 53, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsoner, T.; Vigl, L.E.; Manck, F.; Jaritz, G.; Tappeiner, U.; Tasser, E. Indigenous livestock breeds as indicators for cultural ecosystem services: A spatial analysis within the Alpine Space. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 94, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre-European Commission. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; Nardo, M., Saisana, M., Saltelli, A., Tarantola, S., Hoffman, A., Giovannini, E., OECD, Eds.; OECD Publication: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 1–160. [Google Scholar]

- Žibert, M.; Rozman, Č.; Škraba, A.; Prevolšek, B. A system dynamics approach to decision making tools in farm tourism development. Business syst. Res. 2020, 11, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pažek, K.; Prišenk, J.; Bukovski, S.; Prevolšek, B.; Rozman, Č. Multicriteria assessment of the quality of waste sorting centers—A case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prišenk, J.; Rozman, Č.; Pažek, K.; Turk, J.; Bohak, Z.; Borec, A. A multi-criteria assessment of the production and marketing systems of local mountain food. Renew. Agric. Food Syst 2014, 29, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanan, D.; Burnley, S.; Cooke, D. A multi-criteria decision analysis assessment of waste paper management options. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibowo, S.; Deng, H. Multi-criteria group decision making for evaluating the performance of e-waste recycling programs under uncertainty. Waste Manag. 2015, 40, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlovič, M.; Cerenak, A.; Pavlovič, V.; Rozman, Č.; Bohanec, M. Development of DEX-HOP multiattribute decision model for preliminary hop hybrids assessment. Comp. Elect. Agric. 2011, 75, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Carbone, A.; Caswell, J.A.; Sorrentino, A. A multi-criteria approach to assessing PDOs/PGIs: An Italian pilot study. Int. J. Food Syst. Dynamics 2011, 2, 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Vindiš, P. Multiparameter Model of Evaluation of Energy Plants for Processing into Biogas. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Maribor, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Hoče, Slovenia, 16 April 2010; 153p. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanec, M. DEXi: Program for Multi-attribute Decision Making, User’s Manual Version 3.00. IJS Report DP-9989. Jozef Stefan Institute: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2008. Available online: http://kt.ijs.si/MarkoBohanec/pub/DEXiManual30r.pdf(accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Štambuk, A. Multiparametric hierarchical model of hotel service quality assessment. Master Thesis, School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 9 December 2002; 128p. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanec, M. DEXi: Program for Multi-Attribute Decision Making User’s Manual. 2015. Available online: https://kt.ijs.si/MarkoBohanec/pub/DEXiManual500.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Filipič, N. Multi-Criteri Decision Models for Evaluation of Traditional And Indigenous Horse Breeds. Master Thesis, University of Maribor, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Hoče, Slovenia, 26 March 2021; 80p. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanec, M.; Zupan, B.; Rajkovič, V. Applications of qualitative multi-attribute decision models in health care. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2000, 58, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, Č.; Potočnik, M.; Pažek, K.; Borec, A.; Majkovič, D.; Bohanec, M. A multi-criteria assessment of tourist farm service quality. Tou. Manag. 2009, 30, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingley, M.; Boone, J.; Haley, S. Local food marketing as a development opportunity for small UK agri-food business. Int. J. Food Syst. Dynamics 2010, 3, 194–203. [Google Scholar]

- Belton, V.; Stewart, J.T. Multiple criteria decision analysis. In An Integrated Approach; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Massachusetts, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).