1. Introduction

Gastronomic heritage and traditional and authentic gastronomy are significant factors for tourism development [

1,

2]. Gastronomic heritage is a part of cultural heritage which has been the subject of numerous research works recently [

3,

4,

5]. The national cuisine, specific to a place, characterizes the local culture and is considered to be authentic cuisine [

6,

7]. It is also a tool for attracting tourists seeking authenticity [

8]. Preserving the gastronomic heritage serves not only to attract tourism, but is also territorial capital offering social and economic benefits for local areas [

9], and contributes to preserving the uniqueness of the different ethnic groups in the area [

10,

11].

Many tourist destinations and restaurants have recognized the significance of the potential for tourism development and have started to promote and offer their traditional specialties and cuisine [

12,

13]. This affected restaurants to start notably offering and promoting authentic and traditional food [

14]. The search for authentic and traditional cultural experiences is one of the primary motivators for tourists visiting ethnic restaurants [

15]. Therefore, the authenticity of a dish has been recognized as an added value in restaurant offerings [

16]. For this reason, gastronomic heritage [

1,

17], traditional food [

12,

18,

19,

20,

21], local food [

22], and authentic food have become the research subjects of numerous studies [

23,

24]. This research, which is important for this type of study, as well as other representative research will be mentioned in this paper.

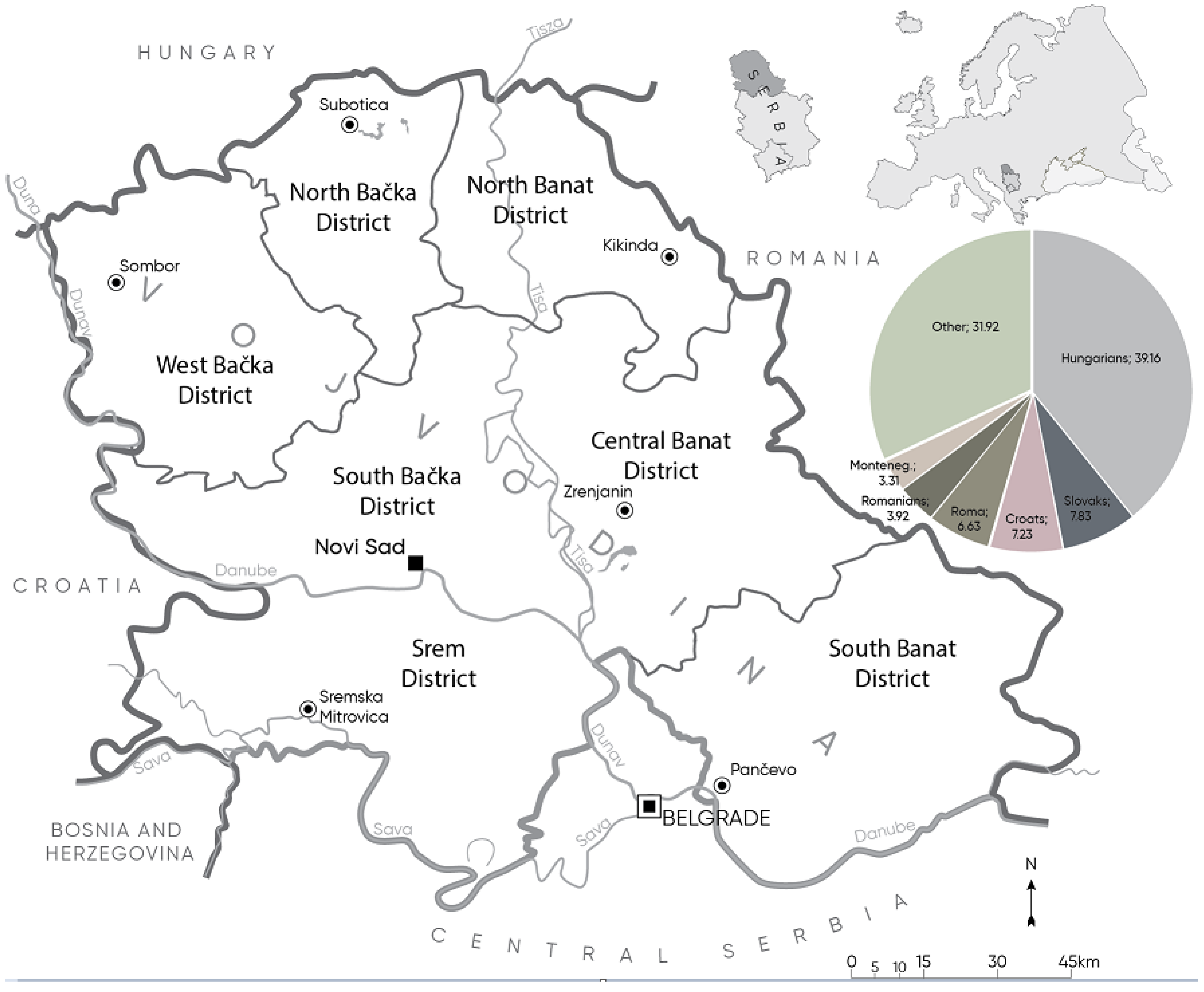

The place of research for this issue was Vojvodina. Vojvodina is an autonomous province in the north of the Republic of Serbia [

25]. The capital city of the province is Novi Sad, a tourist center in the South Bačka District on the Danube river, which attracts a large number of tourists with different motives for visiting [

26,

27]. According to the 2011 census of Serbia, the territory of AP Vojvodina had a population of 1,931,809 [

28]. Two-thirds or 66.8% of the population are Serbs, while ethnic minorities, of whom there over 30, include Hungarians as the most numerous, making up 13% of the population; followed by Slovaks at 2.6%; Croats at 2.4%; Roma at 2.2%; Romanians at 1.3%; Montenegrins at 1.1%; and other peoples represented with a share of less than 1% (Bunjevci, Rusyns, Albanians, Bulgarians, Gorani, Yugoslavs, Macedonians, Muslims, Germans, Russians, Slovenes, Ukrainians, Czechs, etc.), who make up of total of 10.6% of the population in Serbia [

29,

30]. This structure of the population has generated interest in conducting different studies, including this one [

31]. The position of the Vojvodina region in the map of the world with its districts and structure of ethnic minorities, accounting for 30% of the total population, is shown in

Figure 1.

An ethnic group or ethnicity/people (Greek ἔθνος (ethnos)—‘people’) as a relevant factor in the development of gastronomic specificities of Vojvodina is a socially defined category of people who identify each other based on common ancestors as well as national, social, and cultural similarities. Common to ethnic groups are cultural heritage, ancestors, origin myths, history, homeland, language or dialect, and even ideology, and these are manifested through symbolic systems such as religion, mythology, rituals, cuisine, clothing style, and art [

10]. It is important to mention the definition of an ethnic minority. An ethnic minority can be defined as a larger group of people, representative in number in relation to the rest of the population, which is not politically prominent, and which has its own ethnic characteristics [

30,

32]. In the law on the protection of rights and freedoms of national minorities [

32], a national minority shall be understood to mean any group of citizens of the Republic of Serbia that is representative in terms of its size, although it represents a minority in the territory of the Republic of Serbia, belongs to some of the population groups that have lasting and firm ties with the territory of the Republic of Serbia, has characteristics (such as those relating to language, culture, national or ethnic affiliation, descent or religion) which make them different from the majority population, and the members of which are characterized by concern for the collective preservation of their common identity, including culture, traditions, language, or religion [

32,

33].

Vojvodina is inhabited by a large number of ethnic groups, which have, each in their own way, managed to preserve the dishes and customs of their ancestors, despite different external influences [

34]. Vojvodina is a multicultural region where a large number of cuisines are present, which gives it uniqueness and authenticity [

35]. The specific ethnic structure of Vojvodina with its gastronomic characteristics helped it to become an affordable destination for tourism development [

11]. The cuisine of Vojvodina Hungarians and Slovaks is hot and spicy with a lot of meat. The gastronomy of Croatians is characterized by dough specialties. The gastronomy of Vojvodina Romanians is characterized by soups and porridges, Montenegrin gastronomy is characterized by meat, fish, dairy products, and meat products, and Roma gastronomy by its simplicity and specific methods of processing and combining food [

35].

The subject of this paper is the tourist potential of the gastronomic heritage of minority ethnic groups inhabiting the Vojvodina region (Northern Serbia). This research included the preservation and representation of authentic and traditional dishes in homes and restaurants, focusing on the potential for attracting tourists and placement in tourism.

The task of this paper was to obtain data on the degree of preservation and representation of authentic dishes that represent a part of the traditional gastronomy of different nations inhabiting this region. The research provided insight into the state of preservation of gastronomy in homes (one’s own, of descendants, and of co-nationals), as well as the representation in hospitality offers, through examining the opinions on the positioning and placement of these dishes in the touristic market.

The aim of the paper was to answer the following research questions through the research conducted among ethnic groups in Vojvodina:

Q1: What is the degree of preservation of ancestral dishes in the homes of the respondents, their descendants and co-nationals, and restaurant facilities, and are there any differences between ethnic groups?

Q2: To what extent has the authenticity of dishes by type been preserved in restaurant facilities?

Q3: Which part of Vojvodina and which dishes of which ethnic group have the potential to attract tourists?

Q4: What activities would contribute to a better recognizability of Vojvodina’s food in tourism?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Questionnaire

The research was conducted using a questionnaire modelled on similar research [

11,

51]. The questionnaire consisted of four parts.

The first part of the questionnaire was designed to collect the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents (gender, age, education, marital status, ethnicity, employment status, region/district, income).

The second part of the questionnaire referred to collecting data on the preservation of food preparation according to authentic recipes, which was done using a ten-point Likert-type scale of four items—preservation in the household, in the homes of descendants, in the homes of co-nationals, and in restaurants [

51]—where 1 is the least preserved and 10 is the most preserved.

The third part of the questionnaire was intended to collect data on the representation of dishes (by groups of dishes) of ancestors in the offerings of restaurants in Vojvodina [

11] as well as on the authenticity in their preparation [

51]; the obtained data were operationalized on a five-point Likert-type scale: 1—nothing is represented/authentic, …, 5—all dishes are represented/authentic. Both scales contain 10 items, i.e., they include 10 groups of dishes offered in hospitality facilities.

The last part of the questionnaire consisted of four questions referring to the potential of Vojvodina districts for attracting tourists based on the diversity of the offered food of ethnic minorities, the most authentic dishes of minorities on offer, dishes with the potential for placement in tourism (possibility to choose up to three answers per ethnic minority), and suggestions for the development of gastronomic tourism in Vojvodina (as an open question).

3.2. Sampling

The research was performed by conducting a survey questionnaire among ethnic minorities in the territory of Vojvodina. The sample was proportionate to the number of ethnic minorities in the region according to the data provided by the Republic Bureau of Statistics in 2016. The share of ethnic groups is mentioned in the introduction of this paper.

The research was conducted through cultural, art, and educational organizations that deal with the preservation of the languages, music, dance, culture, and tradition of these ethnic groups in Vojvodina. The questionnaire was distributed electronically. All respondents were acquainted with the type of research and the anonymity of the questionnaire. The research was conducted from October 2020 to May 2021. Due to the slow collection of completed questionnaires, the respondents were repeatedly reminded to fill them. In order to obtain data, 650 surveys were distributed, of which 619 were correctly filled and statistically processed.

3.3. Statistical Methods of Work

To obtain answers to the asked questions, the collected data were subjected to statistical procedures by using software for social sciences, SPSS v23.00. The reliability of the psychometric scales was assessed by the use of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Descriptive statistics (frequencies (f), arithmetic mean (M), standard deviation (SD)) was used to describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample, to determine the level of preservation and representation of traditional dishes, to determine the recipes of ancestors used in preparing dishes in homes of the respondents and their descendants, co-nationals, and hospitality facilities, as well as for the description of respondents’ answers regarding suggestions made for better recognition and placement of food in tourism. A paired sample t-test was used for to test the differences between means on the examined variables (the degree of representation and preservation of traditional dishes and types of dishes) and ANOVA (LSD post hoc) was used to test the differences between minority groups. The level of statistical significance was defined at the alpha = 0.05 level.

4. Results

4.1. The Analysis of the Social and Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

The research included 619 respondents (

Table 1), of which 63.8% were female and the rest were male. Adults (adults) with an average age of 38.43 years (SD = 11.47) participated in the research. The first two age categories include the age of early maturity, and the third included medium and late maturity [

58]. Respondents belonging to the age of early maturity were divided into two categories—the young (up to 30 years of age) and other respondents of early maturity (31–40)—while respondents of medium and late maturity were classified in the category over 40 years of age. The most represented were respondents over the age of 40, with a share of 39.6%, and the rest of the respondents were in groups aged between 31 and 40 (34.7%) and up to 30 (25.7%).

Regarding the educational structure, most of the respondents, 63.5%, completed higher education or university, 33.6% of the respondents completed secondary education, and only 2.9% of the respondents completed primary education only. Most of the respondents were employed (76.4%), while 20.2% were unemployed and 3.4% were pensioners.

In order to gain insight into the community, which may be related to the place of food preparation and consumption (at home, in a restaurant), the marital status of respondents was investigated. The highest number of respondents (48.1%) were married, 22.5% were single, 19.7% were in a partner relationship, and the lowest number of respondents (9.7%) did not want to declare themselves.

To gain insight into the home budget, which can be related to the method of obtaining food (independent production), the income per home member was examined. The answer to this question was not required in the questionnaire, and 311 respondents provided an answer. The highest percentage of respondents had an average income of 350 to 500 Euros with a share of 40.8%, 29.9% of respondents had an income of over EUR 500, and 29.3% had an income of up to EUR 350.

The research included respondents of the Hungarian minority (38.1%), the Slovakian minority (7.6%), the Croatian minority (7.3%), the Roma minority (6.1%), the Romanian minority (5.5%), the Montenegrin minority (5.3%), and other minorities in the territory of Vojvodina (30%) with a share of less than 1% each (Bunjevci, Rusyns, Albanians, Bulgarians, Gorani, Yugoslavs, Macedonians, Muslims, Germans, Russians, Slovenes, Ukrainians, Czechs, and others) (

Table 2).

The highest percentage of respondents (35.9%) to the research were living in the territory of South Bačka District, 16.3% of respondents were from North Bačka District, 13.4% were from Srem District, 12.6% were from South Banat District, 10.7% were from West Bačka District, 6.6% were from Central Banat District, and 4.5% were from North Banat District.

To gain a better insight into their knowledge of the restaurant offering, we asked how often they visited hospitality facilities for food and beverages, and 49.3% stated that they visited them more than twice a month, which is appropriate for this type of research (

Table 3).

4.2. The Analysis of the Degree of Preservation of the Recipes of Ancestors

The first research question was to obtain information on the degree of preservation of ancestral food in the homes of respondents, in the homes of their descendants and co-nationals, and in restaurant facilities, as well as whether there are differences between ethnic groups (Q1).

The respondents were asked about the preservation of dishes made according to the recipes of ancestors in their homes, the homes of their descendants, the homes of their co-nationals, and in hospitality facilities. The overall arithmetic mean for the whole scale was M = 6.46 (SD = 1.78), skewness = −0.306, and kurtosis = −0.267. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.806) indicated the very good reliability of the scale [

59]. The obtained results presented in

Table 4 show that the respondents believe that their homes largely nurture their culture and tradition of food preparation (M = 7.08; SD = 2.14), that is, the authenticity of the recipes of ancestors is mostly kept, whereas these dishes are least represented in hospitality facilities (M = 5.83; SD = 2.39).

The paired sample

t-test tested the differences in the answers of the respondents (mean), and the results show, as expected, that the most pronounced difference is between the assessments of the authenticity of recipes in the respondents’ home and hospitality facilities (t = 12.513,

p < 0.001), though differences are also manifested in all other combinations (pairs of variables). The respondents are of the opinion that dishes prepared in their own home and the homes of co-nationals differ the least according to the degree of preservation of ancestor recipes (t= −2.129,

p < 0.05). The answers of respondents and the

t-test results are presented in

Table 4.

Researching the authenticity of traditional dishes within the included minority groups, we found differences in the degree of authenticity in the preservation of food preparation in households (F

(6.

612) = 3.304;

p < 0.01) and hospitality facilities (F

(6.

612) = 6.894;

p < 0.001). The presented results show that the highest degree of the authenticity of dishes is in Slovakian homes (M = 7.70; SD = 1.71), and the lowest degree is among members of the Roma minority group (M = 6.03; SD = 2.85). The research has shown that members of the Croatian ethnic minority group believe that their dishes are the most authentic in hospitality facilities (M = 6.64; SD = 2.01), and the least authentic are dishes of the Roma ethnic minority group (M = 4.53; SD = 2.20) (

Table 5).

The LSD post hoc test shows that the Roma minority has a significantly lower score than all the rest, with the exception of the Romanian, with regard to the preservation of dishes in one’s own home, except for the Montenegrin minority when they are observed in hospitality facilities. Hungarians have a significantly lower score than Slovakians, while among others there are no significant differences with regard to the preservation of dishes in one’s own home. In terms of the degree of authenticity in hospitality facilities, the Montenegrin minority has a significantly lower score than the Hungarian and Croatian minorities. Others have a significantly lower score than Hungarians, Slovaks, and Croats.

4.3. The Analysis of the Representation and Authenticity of Dishes of Ethnic Groups in Hospitality Facilities

The second research question had the task of obtaining data on the extent to which the authenticity of the preparation of dishes of national minorities offered in restaurants of Vojvodina is preserved, observed by groups of dishes (Q2).

Responding to the scale of the authenticity of dishes of ethnic groups in hospitality facilities, the subjects displayed different levels of agreement with the statements, from complete agreement to complete disagreement. The overall arithmetic mean for the whole scale was 3.04 SD = 0.83, skewness = −0.310, and kurtosis = 0.385. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.958) indicated the high reliability of the scale. The overall arithmetic mean for the whole scale of the representation of dishes of ethnic groups in hospitality facilities was M = 2.92; SD = 0.86, skewness = −0.154, and kurtosis = 0.156. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.964) indicated the high reliability of the scale.

The analysis of average grades lea to the knowledge that cattle meat dishes are most represented in the offer (M = 3.18; SD = 0.95), and cold starters (M = 2.89; SD = 0.92) are least represented. According to the respondents’ opinion, the most preserved are ancestor recipes (authenticity), those of cattle meat dishes (M = 3.07; SD = 0.99) and poultry dishes (M = 3.05; SD = 0.99), while the least authentic recipes are of cold starters (M = 2.79; SD = 0.96) and sauces (M = 2.79; SD = 1.02) (

Table 6).

By comparing the results obtained by answering these two questions (representation and authenticity), we notice that the respondents believe that ancestor dishes prepared in hospitality facilities in Vojvodina are more represented regarding the preservation of recipes. Namely, except for poultry dishes, where there is not a statistically significant difference regarding the representation and authenticity of recipes, with all other types of dishes, there is a statistically significant difference—ancestor dishes are present but the authenticity of recipes is significantly absent from the preparation of dishes (

Table 6).

4.4. The Analysis of the Potential for the Development of Tourism

The third research question referred to the food potential of ethnic groups. The task was to obtain answers to the questions of which district of Vojvodina has the greatest potential for attracting tourists based on the diversity of dishes offered by ethnic minorities, as well as whose dishes are the most authentic and whose should be more represented in the restaurant offerings in Vojvodina (Q3).

The first part included a question on which district has the greatest potential to attract tourists based on the diversity of the offer of dishes of ethnic minorities, and the highest number of respondents answered in favor of South Bačka District (39.6%) followed by North Bačka District, also with a high percentage (23.1%) (

Table 7). It is interesting to observe that ethnic minority groups do not see the potential for tourism development based on these dishes in other districts (below 10% per district).

Table 8 shows the structure of answers of respondents to the question of whose dishes are the most authentic in the offerings and whose dishes should be more represented. The question of which ethnic minority dishes should be more represented (the potential) had the option of giving multiple answers (i.e., ethnic cuisines). Dishes of an ethnic minority that respondents stated should be more present in the hospitality offerings, which in the opinion of respondents have the greatest potential to appeal to tourists, were Hungarian dishes (77.1%), and of all ethnic minority groups in Vojvodina, Hungarian dishes were also identified as the most authentic in the hospitality offerings (75.8%).

4.5. The Analysis of Suggestions for Better Placement of Food in Tourism

The last part of research had the task of finding the answer to which activities would contribute to a better positioning of gastronomic heritage in tourism in Vojvodina (Q

4) (on the sample of 18%,

n = 109). The question on suggestions for better recognition of food in tourism in Vojvodina had the option of giving multiple answers. The most respondents proposed amendments through manifestations (39.4%); followed by marketing (38.5%); authentic, traditional, national dishes (33%); and authentic, national, local ingredients (30.3%) (

Table 9).

5. Discussion

5.1. Preservation of Gastronomic Heritage

Observing the results obtained on the degree of preservation of ancestral food in the home of respondents, their descendants and co-nationals, and restaurant facilities (Q

1), it was found that the respondents are of the opinion that the greatest preservation is in their homes, and the least is in restaurants. This was shown by previous research, emphasizing the large number of dishes of international origin in relation to domestic and national [

35]. The results indicate that the offer of restaurants must be improved, because as already mentioned, only authentic gastronomy as a reflection of gastronomic heritage is the basis for development in tourism and attracting tourists motivated by food [

34].

Observing the differences in the answers between the ethnic groups, it was found that the most preserved gastronomy of Slovaks is in the households of the respondents, their descendants, and co-nationals. Slovak gastronomy is characterized by the use of different types of meat specialties and quite spicy foods, as well as different dough dishes that have survived to this day [

34]. Research has shown that the greatest preservation of Croatian food is in restaurants. The reason for this result is a small difference in the perception of the diversity of gastronomic characteristics of the cuisine of the Serbs in Vojvodina, which dominate in the number of inhabitants, and Vojvodina Croats [

56]. The lowest values of all assessed parameters were obtained from the respondents of the Roma national minority. The reason for this is their small number and assimilation with other ethnic groups, which did not enable the preservation and distribution of their dishes [

57].

5.2. Authenticity of Dishes in Restaurants

Examining the extent to which the authenticity of dishes of ethnic groups by types of dishes in restaurants has been preserved (Q

2), it was found that the most common dishes are those with beef, pork, lamb, and similar, and the least represented are dishes served at the beginning of the meal as a cold appetizer. Cold appetizers served in Vojvodina are a combination of different meat products (dried, smoked meat, sausage products), cheese, canned vegetables, and dough [

35], and they are a mixture of specialties of all ethnic groups [

57].

The research has shown that authentic dishes on offer also belong to the group of dishes made with beef, pork, veal, and other types of meat, as well as poultry (hen, chicken, turkey, duck, helmeted guinea fowl, etc.). The least authentic dishes on offer belong to the group of the abovementioned cold starters, as well as sauces. Sauces which are represented are basically of the kind also defined in French cuisine (white sauce, red sauce, etc.) and as such are prepared all around Europe [

35].

Statistically significant differences in the representation and authenticity of dishes prepared from poultry were not found, in contrast to other analyzed groups of dishes. Poultry is widely used in the daily life of the inhabitants of Vojvodina [

35], so it is assumed that this is the main reason for this structure of responses and results.

5.3. Gastronomic Heritage as a Potential in Tourism

Researching which part of Vojvodina and the dishes of which ethnic groups have the potential to attract tourists (Q3), we found that the respondents believe that North and South Bačka districts have the potential to develop tourism and attract tourists with their gastronomic heritage. These two regions are more economically developed, with a greater population density when compared to others, which also refers to ethnic groups researched in this paper.

The study found that Hungarian dishes are considered to be the most authentic and the respondents believe that they should be more represented; therefore, they have a good potential to attract tourists. Hungarian dishes are very popular due to their specificity, which relates to combinations of spices, various sweet and salty flavors, meat dishes, and dough dishes [

35]. Due to their popularity among tourists, some dishes have taken on the epithet of “international”, such as goulash, paprikash, and porkolt [

11]. It is interesting that, except for Hungarian dishes, the authenticity of the dishes of other minorities is significantly lower, while respondents believe that dishes of other minority groups, in addition to Hungarian and Slovakian, have the potential for tourism development.

5.4. Positioning of Gastronomic Heritage in Tourism

By observing the structure of suggestions for better positioning of food in tourism (Q4), we see that manifestations take the first place. Manifestations included several suggestions, out of which the following stand out: getting acquainted with the gastronomic history of an ethnic minority and designing a gastronomic tour where more ethnic minority dishes could be tasted; familiarizing the market with the history and tradition of Vojvodina villages; promoting dishes at various events; and visiting associations with the character of ethnic minorities.

As far as marketing is concerned, the following suggestions stand out: greater wine promotion, better promotion of dishes of ethnic minorities, promotion of hospitality in Vojvodina, working on marketing, additional information about the offer, and better promotion of food through open kitchens.

Authentic, traditional, national dishes included the following suggestions: the use of old, original, well-kept recipes; additional actions with the offer of dishes of ethnic minorities; guests should be presented with a new assortment of dishes; a better offer of dishes; more possibilities to try less familiar products; greater inclusion of local products and dishes in the hospitality offerings; guests should be offered authentic food and beverages; promoting authentic food; offering more dishes of Vojvodina cuisine by restaurant employees; a return to old traditional food and beverages from home recipes; adding pictures to the menu and a description of dishes of ethnic minorities; a more adequate and more attractive offering of dishes of ethnic minorities; and promotion of food with an authentic geographic origin.

Authentic, national, local ingredients included the following suggestions: using only local ingredients, the authenticity of the origin of ingredients, better promotion of national products, and more kinds of national wines and brandies in the hospitality offerings.

All of the above confirms the awareness of the respondents of possible activities to better position gastronomic heritage in tourism of Vojvodina.

6. Conclusions

In Vojvodina, the uniqueness of life consists of multicultural, multinational, multilingual, and multi-religious content, which belongs to wider cultural circles of Central Europe and the Balkans [

11,

35]. Centuries of migrations in this area have led to the existence of numerous ethnic groups in a small area of Vojvodina. Many groups have survived to this day [

29].

By researching the potential of cuisines of the Vojvodina ethnic minorities that inhabit the region, with the aim to obtain data on the possibility of offering authentic gastronomy in tourism, we concluded that traditional segments significant for attracting gastronomic tourists are present and they can be implemented as such into the tourism of rural as well as urban areas through various offers. The inclusion of dishes of ethnic minorities in the hospitality offerings of Vojvodina is at a low level, as is the authenticity.

To develop tourism directed at authentic food, additional work is required on the sustainability of the preserved gastronomic segments and their inclusion into hospitality facilities, which would affect the habits of demand of inhabitants who have long forgotten these authentic flavors. An improvement of the authentic offerings would affect the creation of a more unique offering that would contribute to an authentic experience of a tourist destination through manifestations (promotion of food and beverages), marketing, authentic and traditional national dishes, authentic and traditional local ingredients, diverse offerings, the authenticity of a destination, food quality and safety, the associations of ethnic minorities, marketing research, cooperation, the education of managers and employees, the help of state and industry, and affordability.

Considering all the above, we may conclude that Vojvodina, with its ethnic structure and gastronomic heritage, has the potential to attract tourists motivated by authentic food. The implementation of gastronomic heritage in tourism requires a better placement of authentic products of ethnic groups in restaurants.

6.1. Research Limitations

Limitations in the research are related to the scope and specificity of the topic, which is not fully suitable for research using quantitative methods. The manner in which this research was conducted could not provide more detailed information on the preserved gastronomic heritage of individual ethnic groups (food products, individual dishes, methods of preparation, and consumption). A more detailed insight into the gastronomic heritage with concrete examples of dishes and habits in their preparation and consumption could be obtained by conducting qualitative research.

6.2. Indication of Future Research

In order for this research to gain real value, it is necessary to conduct additional qualitative research among the population. Of particular importance would be the examination of the attitudes of employees in tourism and hospitality of Vojvodina on the need for better placement of dishes of ethnic groups in restaurants. The same survey should be conducted among tourists visiting the region. Surveys of tourists could determine the main reasons for their choice of food and interests and motives for authentic food and food of different ethnic groups inhabiting the region.

6.3. Practical Implications

The practical application of these results is reflected in the data that provide insight into the perception of residents of different ethnic groups on the structure and offerings of food. The obtained results can affect the improvement of the authenticity of the gastronomic offerings of catering facilities, which will have a positive impact on the satisfaction of tourists looking for authentic food.