Abstract

Solar parks are well-defined areas developed in the high solar potential area, with the required infrastructure to minimize the potential threat for the developers. Land occupancy is a major concern for the solar park. The government policy mostly emphasizes the use of waste-degraded land for solar parks. In a competitive energy market, any attempt to use waste-degraded land parcels, without policy regulatory support, can bring large-scale disruptions in the quality and cost of power. The present study investigates the potential of using waste degraded land, with a focus on the impact on the cost of generation and decision making. The study investigates the possibility of including the cost of the externalities in the overall cost economics, through policy and regulatory interventions. Data related to India has been considered in the present analysis. Results show that there are less socio-economic and ecological impacts in using wastelands, compared to land, in urban-semi urban areas with an opportunity cost. Thus, the policy and regulatory interventions could promote wasteland utilization and lure favorable decision-making on investments.

1. Introduction

A solar park is a fast and effective method to integrate clean energy, as a substitute for fossil fuel, into the grid. The type of land, business model, land acquiring method, and proximity to grid infrastructure are key factors that dictate the unit cost of power generation in ground-mounted solar plants. Ground-mounted solar plants need a large amount of land area, with the possibility of socio-economic and ecological impacts, depending on the location of the plant. Land occupancy for long periods, as well as land transformation from its original nature, are key factors that contribute to these environmental impacts. The impact of such externalities is complex to account for, considering the uncertainty, plurality, and lack of a single monetary measure standard.

India is a geographically diverse country, with a vast amount of waste degraded land parcels, spread in different agroeconomic regions. Though large patches of these waste lands have good solar irradiation, their use for solar projects can have additional capital, i.e., operation expenses to overcome challenges posed by land terrain and infrastructural facilities for power evacuation. As one of the largest GHG emitters, India is committed to achieve 175 GW of renewable energy, of which, 100 GW will be solar power [1]. In a competitive energy market, the use of such land parcels can have disruptions in energy mix on volume and price, derailing commitments on global warming.

The development of large-scale solar parks is a fast mechanism to promote ecologically sustainable energy to meet the commitments on climate change initiatives [2] The relation between solar energy and economic development can be understood, in terms of energy security and the accessibility to electricity. As per [3] with annual per capita electricity consumption of 2000 kWh, approximately 3400 TWh per annum would be the energy required for the country by 2070, for which, approximately 38,313 sq. km of land will be required for integrating energy sources. The falling prices of solar PV components, favorable policies, and magnitude of projects have made solar feed-in-tariffs (FiT’s) as low as INR 2.44/kWh [4]. Similarly, the FiT’s for wind power has fallen to INR 2.44/kWh in February 2018 [5]. The cost of the land and its development cost put together will be approximately 40–50% of the total project cost in ultra-mega solar power projects. A one-megawatt (MW) ground-mounted solar PV power plant requires approximately 5 acres of land [6]. According to studies by [1], to fulfill the renewable energy targets kept by India in 2022, approximately 100,000 sq. km land will be required, and with unfocused implementation strategy, there can be a loss of cultivable land with socio-environmental impacts. In Europe, the legislative frameworks allow subsidies and incentives for promoting solar energy. However, the support from these initiatives is not provided to projects that are located in agricultural land. This has stopped land grabbing and selling/renting cultivable land for mere revenue [7]. In India, the use of hot–cold deserts, canal bunds, floating water bodies, and highway sides, etc., for large solar parks, are promoted, while there are no mandatory clauses to use them. There are no existing subsidies or incentives for use of the same, while the use of such land can be mandated on government initiated projects [8]. The solar power plant developer (SPPD) can choose the land, if there are no ambiguities on the land title, while the park should have transmission facilities, internal roads, irradiation, and access. This automatically drives the selection of land to peri-urban and village areas, rather than using waste degrade land banks.

Acquiring big land banks for solar projects is tough, which requires displacement of men and resources, often affecting the livelihood activities of the village. Researchers identified that land occupancy for large solar parks could affect food security, in terms of changes in land-use patterns, loss of natural vegetation, loss of topsoil, and displacement of manpower [9]. Crowdfunding in mega projects shall meet initiatives to tackle climate change, identifying the need of the farmers and incorporating them at the design level [10]. Large land cover, due to solar parks, can affect the properties of photosynthesis, due to lack of reach of sunlight, and could affect the carbon sequestration properties of soil for decades [6]. There is an average temperature rise between 3° C below the solar panels in temperate climatic conditions [9]. High temperatures will affect the efficiency of the PV, since the internal resistance is increased beyond the capacity of the material in cells [11]. Hence, the location of the plant and the suitable cell technology are important. According to [12], land utilization vegetation mix and occupation should go hand-in-hand. In the studies conducted by [13], the groundwater retention is dependent on the type of vegetation and activities that are done on top soil. The geographically fragile environments, intense human activities and climatic variation has influenced the precipitation–evaporation mechanism affecting regional water balances and distribution, leading to water retention and reduction in runoffs [14]. Geographical islands have a challenging environment to test renewable energy integration strategies, as well as cutting-edge technologies, due to the alternation between actual grid-connected and island modes [15].

The restoration of the landscape and vegetation after mega projects will help retain the local population [16]. The top-down and bottom-up approaches to development should consider the justification of land utilization in developmental objectives [17]. Considering the risks involved in mega projects, its wise to invest social capital in eco-environmental projects for ecological improvement [18]. The c-Si and thin-film (TF) PV-based systems have a harmonized median of GHG emissions around the lifecycle around 50 g CO2 eq/kWh, thus further environmental damage during operation should be avoided [19].

The lack of land utilization policy poorly maintained land records, land price ceiling limits, technological impacts, and use of fertile/waste land pattern has delayed many of the solar park projects [4]. Lease of revenue land, lease, and/or purchase of private land are mechanisms to acquire land for renewable energy projects. The biggest challenge in private land lease/purchase is the conversion of fertile land with adverse impacts, due to land occupancy and transformation. While the advantage of using private land is near urban infrastructure facilities, the advantage of using revenue land is low rental costs and utilization of waste-degraded land parcels [20]. Acquiring revenue land for solar projects need approval from various departments; hence, it will be idle to use waste land parcels to minimize the land acquisition hurdles and their impacts [21]. Even though large patches of land in India are classified as waste or degraded land, due to waterlogging, steep slopes, or sandy desert, they could still be used for potential applications, including renewable energy integration, if carefully selected [22]. At least 58% of the total land of India can be considered solar energy-rich, with a solar energy potential of more than 5 kWh/m2/day.

The policy and regulatory guidelines mandate the use of land with good irradiation levels at a clearance ratio of 5 acres/MW, with a priority of waste/non-agricultural land (including hot/cold deserts) to be considered for ground-mounted solar energy projects [20]. However, developers prefer land that is fertile near the urban areas, in order to avoid the cost on excessive networks for transmission lines [21]. Apart from the socio-economic feasibility study, the solar park requires intensive civil infrstructure, which includes drainage, road networks, land conditioning, and power evacuation infrastructure [23].

The factors that have a direct influence on solar PV power generation cost are national policies in line with global commitments to meet climate change, maturity of technology, foreign policies on trade, and the global economy. The type of land, its topography, land acquiring method, the proximity of the land to the grid, infrastructure requirements, solar irradiation level, finance mechanism, and business model are decisive parameters classified under indirect factors [24]. Feed-in-tariff (FiT), feed-in-premium (FiP), and auction are pricing mechanisms used for implementing renewable energy systems as power sources. While FiT and FiP are tariff-based mechanisms, set by price-driven policy instruments, the auction mechanism seeks the best possible price from developers, through a competitive bidding process. India has shifted from feed-in-tariffs to auction mechanisms, as is the case with many nations from the time the prices for solar and wind energy integration have become comparable with fossil fuel integration [20,25].

Accelerated depreciation (AD), generation-based incentives (GBI), and viability gap funding (VGF) were mechanisms used for promoting the large-scale dissemination of solar-based power generation. Renewable purchase obligation (RPO) and renewable energy certificates (REC) were extended for industries for committing to buying/pooling renewable energy power. The renewable energy industry in India is privately led and capital-intensive. The major challenges in investment in renewable energy integration in India are identified as large, geographical divergence, concerning the level of available irradiance, differences in state/federal and central government policies, absence of long term debt financing sources with low-interest rates, anticipated technological leaps in renewable energy, renegotiation of signed power purchase agreements (PPA’s), and the credibility of the utility sector and clear land titles [25].

The literature survey concludes the following findings and limitations.

- (i)

- India has abundant, solar energy-rich wastelands, categorized under different classifications in different states.

- (ii)

- The solar park can address many externalities of fossil-based power plants, while there are adverse impacts on society, economy, and ecology, due to land utilization, land transformation, and lifecycle carbon footprints, which remain as negative externalities, not accounted for in the cost economics.

- (iii)

- Measures to integrate solar energy were heavily incentivized, with solar power reaching par with fossil-based power generation. Any deviation in incentives/policy measures could bring disruptions, concerning quality and reliability.

- (iv)

- While increasing the renewable energy mix in the grid is one key measure to meet global warming, the efficient use of renewable energy hotspots, technology updates with increasing capacity utilization factor, and optimized renewable energy mix in grid remain unanswered.

- (v)

- The policy emphasizes the use of waste-degraded land for solar parks. However, there is no mechanism to measure its use, and there are no incentives to promote the use of wastelands. In a competitive energy market, any attempt to use waste–degraded land parcels, without proper policy interventions, can bring large-scale disruptions in quality and cost of power.

The objective of the current study is to assess the impact on cost economics of solar parks by using different waste degraded land parcels. The study also analyzes policy interventions that can promote the use of wastelands, accounting for the additional expenses in the solar park cost economics.

In Section 2 of the paper, four land parcels, in different land terrains and classified under different wasteland categories, are selected from multiple agro-climatic zones. In Section 3, factors influencing the cost of solar PV-based power generation are discussed, and a sensitivity analysis is done to understand the influence of land characteristics on the unit cost of power generation. Section 4 discusses the factors that influence the decision-making process for investment in grid-integrated, ground-mounted solar energy projects. The last section of the paper discusses the required policy interventions for promoting waste-degraded land for solar parks and options to internalize the additional cost.

2. Selection of Waste Land Parcels for Analysis of the Impact on Power Generation Cost with Land Characteristics

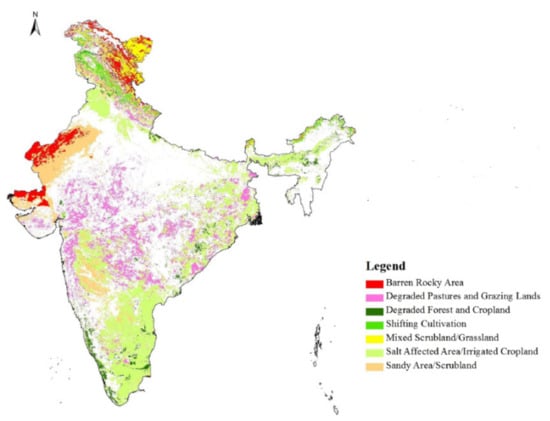

The land cover and annual average global insolation maps of India are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The land cover map shows that there is unutilized, non-agricultural land, spread over different states and classified as barren, fallow, waste, and shrub. Comparing Figure 1 and Figure 2, it is found that the western plains and the Deccan plateau have good irradiation levels, under different wasteland classifications. According to the agroclimatic zone (ACZ) classification, the solar energy-rich states of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Karnataka fall in the Gujarat Plains, western dry region, western plateau, and west coast, respectively [26,27,28]. Table 1 indicates the waste-degraded land classifications for these states, as well as waste land with good solar energy potential.

Figure 1.

Land use and cover of India. Reprinted with permission from [29]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

Figure 2.

Annual average global insolation map. Reprinted with permission from [28]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier.

Table 1.

Wasteland classification and solar energy potential for solar rich states of India. Adapted from [26,27,28,29].

Selection of Locations

For analysis, four locations with good irradiation levels and different wasteland classifications are selected from the states of Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, and Rajasthan. Table 2 provides details of the four locations, with respect to agroclimatic region, wasteland classification, land acquiring method, soil type, and climatic conditions.

Table 2.

Geographical, climatic, and topographical details of four locations were selected for the study.

The state of Karnataka has good solar energy potential in the central and southeastern regions, compared to the southern and northern regions. The state has large patches of wasteland, classified under dense scrub, opens scrub, underutilized degraded forest (scrub domain), and underutilized degraded forest (agriculture). Based on the solar energy potential and waste land pattern, Location 1 is selected in wasteland classification ‘underutilized degraded forest (agriculture)’ in flat terrain [30]. The northern regions of Madhya Pradesh, especially the Shivpuri plateau and Lashkar plain have good solar energy potential. The state has large waste lands classified as underutilized degraded forest (scrub region), land with forest scrub, and land with open scrub. Based on the solar energy potential and waste land classification, Location 2 is selected with wasteland classification ‘open scrub’ in steep slope [28] The state of Gujarat has good solar energy potential in most of its land area, with the maximum centered on the plains and hills of the western region. The waste lands are classified under dense scrub, open scrub, underutilized degraded forest, and land affected by salinity. Comparing the solar energy potential and waste land pattern, Location 3 is selected in the coastal region, with high–low tide region with wasteland, classified as ‘saline soil and waterlogging’ [31].

The state of Rajasthan has good solar energy potential, with solar irradiation levels varying from 5 kWh/m2 to 7 kWh/m2 in the northeastern hills to the plains. The waste lands in the state are largely classified as sands semi-stab region, with heights of 15–40 m. Considering the solar irradiation levels and waste lands, Location 4 was selected, with wasteland classification ‘sands semi-stab region’ [32].

The four locations were selected such that a comparison can be made between the most favorable locations, with respect to the most challenging. For the study purpose, Location 1 is considered a flat terrain, with deep loamy alluvial soil with wasteland classification ‘underutilized—degraded agriculture and categorized ‘agricultural land’ Location 2 is a steep slope, with a deep loamy clayey mix of red and black soil and wasteland, classified as ‘underutilized-degraded forest scrub’ and categorized as ‘waste-degraded’.

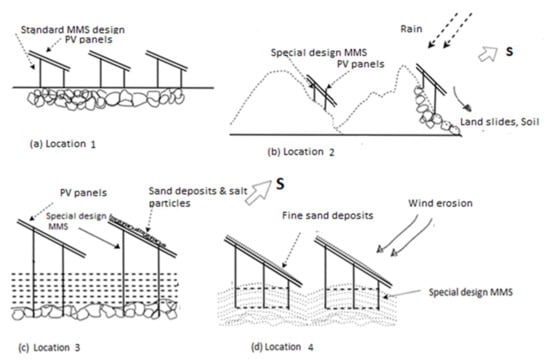

Location 3 is waterlogged with high tide-low tide phenomenon, with waste land classified as ‘saline soil’ and categorized as ‘waste-degraded’. Location 4 is a sandy desert with deep loamy desert soil and wasteland, classified as ‘sand semi stab (15 to 40 m) and categorized as ‘waste-degraded’. The diagrammatic representation of the four locations is explained in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the four locations.

3. Parameters Contributing to Solar PV Based Power Generation Cost

The parameters contributing to the cost of solar PV-based power generation can be majorly classified as fixed (direct) and variable (indirect), as indicated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Direct, variable, and hidden parameters affect the power generation cost in solar PV-based power generation.

While the fixed parameters are based on a broader national interest and commitment to climate change, the variable parameters are site-specific and will depend on the business model [24,25]. The hidden cost, Figure 4, is due to the impact of externalities on land occupancy and transformation concerning society, economy, ecology, and microclimate, which is not considered in the cost economics of solar parks. For the analysis, it is considered that the national policies, regulatory mechanisms, trade policies, and world economics will have an equal impact on all four locations.

Analysis on the effect of land pattern on the power generation cost, with respect to changes to fixed, variable, and hidden cost, are analysed. Table 3 shows the colour coding to interpret the magnitude of impacts, while Table 4 gives the policy and regulatory support for each site with respect to subsidies and benefits of tax. Table 5 gives the civil and infrastructural impacts, while Table 6 gives the impact on the operation and maintance cost. Table 7 gives the impact on th socio-economics of the local population with respect to the solar farm.

Table 3.

Matrix on effect on power generation cost concerning the type of land and accounting for the fixed, variable, and hidden costs.

Table 4.

Policy and regulatorary support for the locations considered for the study.

Table 5.

Impact on the civil and electrical infrastructure stratergy with respect to different site locations.

Table 6.

Impact on the operation and maintenance stratergy of the plant with respect to different site locaitons.

Table 7.

Benefits and impacts on the socio-economic and ecological factors at different sites due to solar plant.

Location 1 is considered the baseline wasteland situation, with minimal constraints and no additional civil–electrical infrastructural cost to the optimal design. Location 2 requires special module mounting structure (MMS) and civil foundations to meet the characteristics of the steep slope land terrain to withstand wind load and soil erosion. Location 2 would also require custom-designed wire ropes for monkey climbing, in order to reach every location of the power plant. Location 3 would require MMS and a foundation design that can withstand saline waters. Location 3 would require a desalination plant as a freshwater source and custom-designed canoes for movement between the solar arrays during the high tides. The PV panels, cable trays, inverters, and balance of materials should be protected from the saline atmosphere, with proper painting, coatings, conduits, etc. Location 4 would require MMS and a foundation design that can withstand wind erosion and desert sand. The solar panels, inverters, and balance of materials should be suitably enclosed to protect fine sand particles. Location 4 would necessarily require pneumatic air cleaners for cleaning the panels, as obtaining water will be almost impossible. The parameters that add to the capital cost in each location is indicated in Table 3.

While considering the operation maintenance of the solar park for different locations, it is seen that Location 1 will have the optimal cost, since the land is flat terrain, near an urban area, and the source of water is available at reasonable depths from the bore well. Location 2 will require routine maintenance of wire ropes used for monkey climbing, transport of workforce from urban areas, and deeper borewells as a water source. Location 3 will require the routine seaworthy painting of the MMS, inverter box, balance of materials, maintenance of desalination plant, and canoes. Location 4 will require maintenance of pneumatic air cleaners, additional manpower to be stationed at the site, and transportation of potable water for minimal requirements at the site. The analysis concludes that the use of waste land will incur additional costs through operation maintenance during the life of the plant.

The environmental impact assessment on Location 1 shows chances of village displacements, since the land is close to urban-semi urban infrastructure. The land will have an opportunity cost, since it could have been used for alternate purposes. Land use and cover will affect the carbon sequestration efficiency of soil, flora–fauna of the land, and water retention capacity of the soil. The land used for Location 2 is classified as waste degraded in a steep slope, hence does not have an alternate use. The impact on water retention, carbon sequestration efficiency, and flora–fauna can be reduced by incorporating design changes in module mounting structure. Since the land is in a steep slope and away from an urban-semi urban area, there will not be any displacement of villages; the only impact would be a hindrance to cattle herding. Location 3 is waterlogged, due to high–low tide and has saline soil. The foundations for module mounting structures will be a one-time civil work, using the piling process. The impact on flora–fauna, carbon sequestration efficiency of soil, and damage to water retention property of soil is almost nil. However, the effect on microorganisms in the water needs to be analyzed. Since the location is far from urban infrastructure, neither livelihood activities nor villages will be displaced. Location 4 is in the desert sand, away from the urban infrastructure, and does not disturb livelihood activities. The land does not have any alternate purpose. The adverse impacts on topsoil, flora–fauna, water retention property, and local vegetation are nil. The only hindrance will be a movement to camel herds. The impact on socio-economic and ecology for the four locations shows that the maximum damage, due to land occupancy and transformation, would occur for Location 1, while Locations 3 and 4 have minimal impacts.

4. Factors Contributing to Investment Decision-Making in Ground-Mounted Solar PV Projects

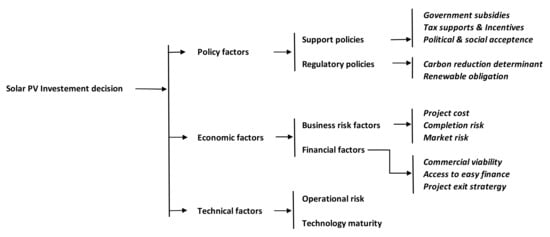

The regulatory obligation for carbon reduction to meet global warming has led to large scale incentives/subsidies to promote solar PV-based power generation. State/federal and central government policies were framed to promote solar energy, which prompted national and international developers to invest in solar power generation in India. The factors that contribute to the power generation cost are generally classified as fixed (direct) and variable (indirect). The fixed factors are national policies and regulatory mechanisms to promote clean energy, foreign trade policies, and tax incentives/subsidies. The variable factors are land characteristics, land procurement strategies, and associated operation and maintenance hurdles. The technical viability of the project, low-interest rates on debt/equity, and financial models play a major role in investment decision-making. The inclusion of waste degraded land for the solar park will increase project risk during design, operation, and maintenance, with adverse impacts on the decision-making process. The indicators in the decision-making process for investment in grid-integrated, ground-mounted solar energy projects are listed in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Structural hierarchy diagram of solar PV investment evaluation indicators.

5. Discussion and Policy Recommendations

Studies on wasteland distribution and solar energy potential, show that there are abundant solar-rich wastelands, classified under different categories. Four locations, with different land topographies, soil characteristics, and agroclimatic zones, were selected to understand the effect of land characteristics on the power generation cost. The assessment shows that the intensity of waste-degraded land classification has a direct impact on the capital and operation expenses, in order to meet the challenges raised by the wasteland. The largest additional expense will be for a custom-designed module mounting structure and civil foundation. The environmental impact assessment on the four locations shows that Location 1 would have the maximum impact, since the land is located near the urban area, which was once used for agriculture. The use of such lands for solar parks can have adverse effects through land occupancy and transformation in the lifecycle of the plant, affecting the society, economy, and ecology of the region. The environmental impact assessment of Locations 2, 3, and 4 show that the impacts on society and economy are almost nil, since there is neither village displacement nor loss of livelihood activities. The lands being steep, saline (waterlogged), and sandy, respectively, do not have damage on ecology, concerning plant and animal species. However, specific studies need to be conducted on the effect of microorganisms in water.

The social, economic, and ecological impacts for Locations 2, 3, and 4 is usually not accounted for in the cost economics of solar parks; hence, not reflected in solar energy production cost. These impacts can be quantified, for economic analysis, under the opportunity cost of land, cost due to damage to ecology, and social cost of carbon. The opportunity cost of land can be defined as the second-best alternative use of the land, if the land was not used for the solar park. The ecology cost is defined as the loss in economy, per acre of land, by implementing the new technology put to operation. The social cost of carbon can be defined as carbon footprint during the lifecycle of the project and loss in carbon sequestration efficiency. The carbon footprint cost should be the sum of emission of carbon during the manufacturing of solar panels, its transportation to site, and during the recycling. The carbon sequestration efficiency should be the soil loss efficiency to capture the carbon dioxide, due to land utilization by solar panels during the lifecycle of the plant.

The analysis concludes that the use of wasteland for solar parks will have additional capital and operation expenses, which could be the major reason for solar park developers to consider good land parcels near urban infrastructure as the location for solar parks. In an energy-intensive and competitive market, the promotion of wasteland for solar parks should need policy-regulatory interventions. Considering the socio-economic and ecological impacts of using agricultural land in urban/semi-urban areas for solar parks, it is more important to promote waste-degraded land parcels for solar parks. Table 8 discusses the existing policy and regulatory framework for solar parks, as well as the required interventions that will enhance the use of waste-degraded land for solar parks.

Table 8.

Existing policy framework and required interventions to promote wasteland for solar parks.

The following policy interventions are suggested for disseminating solar energy through the use of waste-degraded land parcels.

- Solar park bidding should be site-specific, giving weightage to a selection of sites, including land topography and the associated civil and infrastructural costs. The agreed feed-in-tariffs should be in proportionate to the investments made in using the waste land parcels.

- The government should rekindle schemes, such as accelerated depreciation and generation-based incentives, to promote the use of waste/degraded land for the solar park.

- There should be a mechanism to calculate the hidden cost in the cost economics of solar parks, including the opportunity cost of land, the social cost of carbon, and ecology cost. This should be included in the cost economics to be considered as a developmental expense.

- The developmental expense can be a one-time payment to government machinery by the park developer. Whenever a wasteland is used, the developmental expense can be waived off/incentivized.

6. Conclusions

The solar park is a widely promoted mechanism in India, to integrate clean energy into the grid. In an environment with favorable policies, the location of site, land characteristics, and business model are decisive factors of PV-based power generation costs. Large amounts of land, under waste-degraded classifications, are available in different agroclimatic–agroecological regions across India. The reason for land to be classified as waste-degraded is erosion, soil salinity, underutilization, waterlogging, and desert sand. Many of the waste-degraded lands are in solar hotspot regions, with site-specific challenges for construction work. The falling prices of solar panels, market competitiveness, and energy-intensive industry have helped utilities to buy solar power at a very competitive price. While the government mandates the use of wasteland for the solar park, multiple factors have prompted grid-integrated, ground-mounted solar projects to conceive in either agricultural lands, peri-urban, or near the urban periphery.

The present work has considered the impact of capital-operational expenses, society, economy, and ecology, if waste-degraded lands are used for solar parks. A wasteland, under the classification ‘underutilized -agriculture land’ with minimal constraints, is selected as a datum, which is compared with ‘barren rocky steep slope, saline waterlogged and sandy desert land’. The fixed parameters, related to policies, global agenda, and climate commitments, were kept constant for the analysis, while the effect, due to land characteristics, operation maintenance schedules, and environmental impacts, were studied in detail. The decision-making process matrix was made, critical factors on socio-economics and environmental aspects were discussed, and mitigation measures were suggested. The study concludes that there will be a remarkable increase in capital and operation expenses, while using wasteland for the solar park, mainly due to the requirement of custom-designed module mounting structure and civil foundations, to overcome land terrain challenges. There will be a substantial cost increase in power evacuation requirements, as well. However, the study concludes that there are fewer socio-economic and ecological impacts in using wastelands, compared to land, in an urban-semi urban area, with an opportunity cost. While considering the factors that contribute to the power generation cost in solar PV plants, it is identified that the cost towards impacts on society, economy, ecology, and changes to microclimate are not factored in the cost economics. The study concludes and recommends policy interventions, including the opportunity cost of land, social cost of carbon, and ecology cost, which are externality costs on society, economy, and ecology, into the cost economics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.T. and S.S.S.; methodology, S.S.S. and S.J.T.; software, S.T.; validation, R.G. and M.M.A.; formal analysis, S.T.; investigation, S.J.T. and S.S.S.; resources, S.S.S.; data curation, S.J.T. and R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.T. and S.T.; writing—S.J.T. and R.G.; visualization, M.M.A.; supervision, M.M.A.; project administration, S.J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kiesecker, J.; Baruch-Mordo, S.; Heiner, M.; Negandhi, D.; Oakleaf, J.; Kennedy, C.; Chauhan, P. Renewable energy and land use in India: A vision to estimate sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawn, S.; Tiwari, K.P.; Goswami, K.A.; Mishra, K.M. Recent developments in solar energy in India: Perspectives, strategies and future goal. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhatme, S.P. Meeting India’s needs of future electricity through renewable energy sources. Curr. Sci. 2011, 101, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, N.; De, A. Renewable Energy and Grid Integration, Enhancing Ease of Doing Business-Solar Park; White Paper; Government of United Kingdom: London, UK, 2018.

- Bhushan, C.; Bhati, P.; Sreenivasan, P.; Sing, M.; Jhawar, P.; Koshy, M.S.; Sambyal, S. The State of Renewable Energy in India; Centre for Science and Environment: New Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven, D.J.; Capellan-Peréz, I.; Arto, I.; Cazcarro, I.; de Castro, C.; Patel, P.; Gonzalez-Eguino, M. The potential land requirements and related land use change emissions of solar energy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Vrînceanu, A.; Grigorescu, I.; Dumitrașcu, M.; Mocanu, I.; Dumitrică, C.; Micu, D.; Kucsicsa, G.; Mitrică, B. Impacts of Photovoltaic Farms on the Environment in the Romanian Plain. Energies 2019, 12, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selna, S.; Kuldeep, N.; Tyagi, A. A Second Wind for India’s Wind Energy Sector: Pathways to Achieve 60 GW; Centre for Energy Environment and Water: New Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Ghosh, B. Land utilization performance of ground mounted photovoltaic power plants: A case study. Renew. Energy 2017, 114, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoknes, P.E.; Soldal, O.B.; Hansen, S.; Kvande, I.; Skjelderup, S.W. Willingness to Pay for Crowdfunding Local Agricultural Climate Solutions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, A.; Astaraei, F.R.; Ahmadi, M.H. Generation and combination of the solar cells: A current model re-view. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa da Silva, V.; Salami, G.; da Silva, M.I.O.; Silva, E.A.; Monteiro, J.J., Jr.; Alba, E. Methodological evaluation of vegetation indexes in land use and land cover (LULC) classification. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2020, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.; Mohanan, A.A.; Ekanthalu, V.S. Hydrogeochemical analysis of Groundwater in Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu; Influences of Geological settings and land use pattern. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2020, 4, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, K.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, J. Impacts of Climatic Variation and Human Activity on Runoff in Western China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinzadeh, S.; Garcia, D.A. Techno-economic assessment of hybrid energy flexibility systems for islands decarbonization: A case study in Italy. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 51, 101929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zhao, Y. The Characteristics of Rural Settlement Landscape in Hilly Area from the Perspective of Ecological Environment. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, X. The coupled relationships between land development and land ownership at China’s urban fringe: A structural equation modeling approach. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tang, D.; Xu, R. Systemic Risk Infection and Control of Water Eco-Environmental Projects under the Mode of Government-Enterprise Cooperation. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.H.; Ghazvini, M.; Sadeghzadeh, M.; Alhuyi Nazari, M.; Kumar, R.; Naeimi, A.; Ming, T. Solar power technology for electricity generation: A critical review. Energy Sci. Eng. 2018, 6, 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Thapar, S. Addressing Land Issues for Utility Scale Renewable Energy Deployment in India; Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation: Delhi, India, 2017; Available online: shaktifoundation.in (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Rathore, P.; Rathore, S.; Singh, R.P.; Agnihotri, S. Solar power utility sector in india: Challenges and opportunities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2703–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watve, A.; Vidya, A.; Iravatee, M. The Need to Overhaul Wasteland Classification Systems in India. Econ. Political Wkly. 2021, 56, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu, S.; Nehra, V.; Luthra, S. Investigation of feasibility study of solar farms deployment using hybrid AHP-TOPSIS analysis: Case study of India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 73, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohankar, N.; Jain, K.A.; Nangia, P.O.; Dwivedi, P. A study of existing solar power policy framework in India for viability of the solar projects perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, G.K. Green Energy Finance in India: Challenges and Solutions; ADBI Working Paper 863; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/green-energy-finance-india-challenges-and-solutions (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Balasubramanian, A. Wastelands in India. In Country-Wide Class Room Educational TV Programme-Gyan Darshan; University of Mysore: Karnataka, India, July 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, D.; Tewari, S.K. An investigation into land use dynamics in India and land under-utilisation. Ind. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 65, 658–676. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachnadra, V.T.; Jain, R.; Krishnadas, G. Hotspots of solar potential in India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3178–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrasi, A.S.; Abhilash, P.C. Exploring marginal and degraded lands for biomass and bioenergy production: An Indian scenario. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2011, 15, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajjar, J.; Agravat, S.; Harinarayana, T. Solar PV generation map of Karnataka, India. Smart Grid Renew. Energy 2015, 6, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Harinarayana, T.; Kashyap, J.K. Solar energy generation potential in India and Gujarat, Andhra, Telangana states. Smart Grid Renew. Energy 2014, 5, 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, H.; Arora, U.; Jain, R.; Sharma, K.A. Rajasthan Solar Park—An Initiative Towards Empowering Nation; Current Trends in Technology and Science: Noida, India, 2012; Volume II, ISSN 2275-0535. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).