Abstract

In the past three decades, there has been increasing research carried out on the role of heritage and its processes in achieving broader sustainable development objectives beyond heritage conservation. As part of this movement, people-centered approaches and participation have been widely integrated into international regulations and guidelines on heritage management, stimulating the implementation of case studies-based research worldwide. Despite the wide advocacy of participatory heritage practices’ contributions to more inclusive and culturally sensitive local development in a great variety of projects, there is limited research into the roles these practices can have in addressing sustainability objectives. How are these roles addressed in international heritage regulatory frameworks, and what forms of participation are promoted for their fulfillment? This paper seeks to answer this research question through a content analysis of international declarations, conventions, guidelines, and policy documents focused on the roles and forms of participation that are promoted. A crossed-matched analysis of results reveals that active forms of participation are those most used to promote all roles and subcategories of participation, as a right, as a driver, and as an enabler of sustainable development. However, fewer active forms are presented as complementary at different stages of sustainability-oriented heritage practices. Moreover, a higher incidence of generic forms of participation can be observed in documents addressing international stakeholders, while partnership and intervention are to be found in those targeting regional and local actors. Nevertheless, the low incidence of decisional forms of participation confirms the challenges of power-sharing at all scales. Trends and influences are highlighted, informing heritage research, governance, and policymaking, but also revealing gaps and ambiguities in current regulations that further research encompassing a larger number of documents might confirm.

1. Introduction

“Development divorced from its human or cultural context is development without a soul” [1] (p. 17). However, the integration of culture and heritage into sustainable development discourse is an ongoing and longstanding challenge. Critics have been pointing out the pitfalls and incompleteness of the sustainability model proposed in the 1980s based on three dimensions, economic, social, and environmental [2,3], arguing that it neglects crucial dimensions of development, such as governance and politics, spirituality, religion, culture and aesthetics, and the complex relations between them [4,5]. In the 1990s, the report “Our Creative Diversity” [1] and, more broadly, the World Decade for Cultural Development (1988–1997), aimed to place culture at the center of sustainability models. However, the sustainable development agendas published across the 1990s, 2000s and early 2010s by the United Nations did not reference culture and heritage [6,7,8], which renewed the need for more research and stronger advocacy for their role in sustainable development processes [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Despite UN bodies’ increasing association of culture and heritage with sustainable development [2,15] (p. 45), including the intensification of UNESCO’s work since 2010 [16], in 2015 the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda still presented limited mentions of culture across its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 169 targets, and 230 indicators [17]. Heritage is referenced once in Goal 11, aimed at making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable, namely, in target 4 to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage,” limiting the role of culture and heritage practices in the sustainable development agenda [18].

For a broad and effective integration of heritage in sustainable development agendas and processes, however, sustainability also needs to permeate into heritage policies and practices. Even though mention of sustainable development can be found in international heritage regulatory frameworks since the mid-1990s [19,20,21], it was only in 2002, with the Budapest Declaration, that the UNESCO World Heritage processes became explicitly linked to social equity and economic growth [2,22,23], thus impelling heritage doctrines onward. A decade later, other documents adopted a similar approach, advocating a good balance between socio-economic and urban development and heritage conservation [24,25,26]—particularly in the management of the historic urban landscape [27,28,29]—looking inward at the sustainability of heritage attributes and values [30] (p. 5). Contextually, a second trend emerged that looked outward at heritage practices as impacting and contributing to the sustainable development of societies, cultures, and the environment [30] (p. 5).

Different organizations promoted rights-based approaches to heritage management, through declarations, reports, and guidelines [26,31,32,33,34]. In 2015 a new Policy on the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into Processes of the World Heritage Convention was published with the aim to align all World Heritage processes to the post-2015 UN Sustainable Development agenda, influencing future revision of the World Heritage Operational Guidelines [22,30,35]. UNESCO further investigated, regulated, and attempted to measure the impact of culture and heritage on selected SDGs and sustainability dimensions [36,37,38,39]. Other organizations like the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG), and the British Council also explored the links between heritage and the SDGs in the context of cultural [18] and natural heritage [40] management and governance, specifically in urban contexts both at the international [41] and national level [42].

In line with these trends in policies and governance, greater importance has been progressively given to the role of communities’ engagement and stakeholders’ collaboration in heritage management and conservation. Attention to participatory processes has been encouraged by the United Nations since the 1950s [43], following the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [44] (Art. 27.1), as a way of making development programs more efficient and effective [45,46,47,48]. Participation was increasingly acknowledged as fundamental to a sustainable urban development that is respectful of societies’ needs and values [49,50,51] and which therefore integrates their cultural heritage and its practices [52,53,54,55]. Inspired by urban participatory experiences of the 1960–1970s [56,57,58] and influenced by the dissemination of the Brundtland report in the 1980s [59], in the early 1990s participatory processes started being implemented for the inclusive and effective protection and safeguarding of cultural heritage [60,61].

Nowadays, on the one hand, participatory heritage practices are advocated for a better safeguarding of heritage attributes and values. On the other hand, inclusive and collaborative heritage processes along with people-centered and rights-based approaches are recommended to link heritage practices to broader sustainable development objectives [2,22]. Participation is acknowledged and advocated as a human right by international organizations [62,63,64], and since the 1970s it has been at the core of the development of new theories and models of democracy. For instance, according to the principles of participatory democracy, every citizen is entitled to take part in decisional processes over governance matters, has obligations towards their peers, and shares responsibilities and power with institutions and their representatives at multiple scales, holding governmental bodies accountable and fostering everyone’s participation [65,66,67,68,69]. Furthermore, in line with the theoretical precepts of deliberative democracy, citizens can debate in groups, expressing dissent and requesting clarifications, affecting decisions at a macro level to the point of influencing regulations, ideally through shared consensus, ensuring that multiple interests and opinions are heard and met, fostering mutual respect and legitimating democratic processes [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. In this scenario, the empowerment of citizens becomes fundamental. Although it may have several definitions according to different perspectives [79], to empower someone to participate comprises two fundamental requirements: first, to provide access to political structures and formal decision-making processes; and second, to cultivate the required capacity not only in terms of education, information, and knowledge sharing regarding the issues addressed, but mainly by nurturing the awareness of one’s right and power to contribute to change [80,81,82]. While, originally, in the 1970s, these two dimensions of empowerment were clearly recognized—and eventually addressed—the recurrent use of the term in development discourses led to a contemporary understanding of empowerment as a smoother and idealized concept, lightened of some of the important tensions, conflicts, and political strains that it entails [81].

Even though participatory models have been further researched in relation to cultural governance [83,84,85], the implementation of participation in heritage practices still faces many challenges. Particularly in the field of critical heritage studies, much research has explored contemporary relationships between people, heritage, and power that produce an ‘authorized heritage discourse’, seeking to understand how heritage shapes identities and values in the present through constant processes of negotiation and how this affects heritage and development processes, where political strains are always present [86,87,88,89,90,91]. The growth of concern to secure more inclusive and equitable heritage practices and governance is reflected in the growth of references in research and heritage regulatory documents to foster participation in the protection and safeguarding of heritage [92,93,94,95,96,97], in line with the goals of the 2030 Agenda [17].

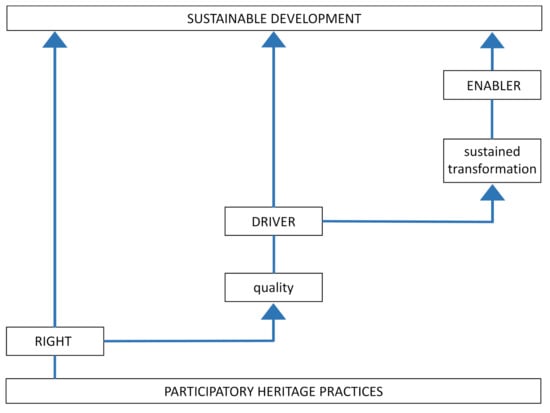

Despite participation being an integral part of international heritage regulation framing the linkages between heritage and sustainability, international documents seldom define it or specify the contribution of participatory practices to the sustainable development objectives [98]. Even though research today is furthering the understanding of the ‘sustainability roles’ of participation, primarily through case studies, comparative studies and the development of theoretical frameworks are limited [99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113]. Recent research identified three main roles of participation in achieving sustainable development objectives—participation as a right, as a driver, and as an enabler—and nine subcategories (see Figure 1) [98].

Figure 1.

Coding of roles of participation and subcategories. Source: Rosetti, Jacobs and Pereira Roders, 2020 [98].

Each role and subcategory make a different contribution to sustainable development objectives. First, the acknowledgment and enforcement of participation as a right can contribute to more equitable and just societies by ensuring the physical and intellectual access of rights holders to their heritage, ensuring their engagement in decision making and the sharing of benefits from its related practices, as an expression of democratic values. Second, the understanding of participation processes as a driver of sustainable development can contribute to heritage conservation, a more resilient living environment and communities, better heritage management and governance, and build tolerance and peace, defusing conflicts. Eventually, participation can be seen as the enabler ensuring that the sustainable development objectives addressed today will be addressed tomorrow [98]. These roles of participation are determined by the quality of its practices, which can be defined by looking at which stakeholders are involved, how and when they engage, and by the sustained transformation of those practices through education, capacity building, and long-term planning (see Figure 2) [98].

Figure 2.

Interconnections between roles of participation [98].

The results of this study revealed trends in the acknowledgment and promotion of each role of participation and their subcategories, without, however, looking at the kind of participatory practices promoted. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet researched the relation between the forms of participation recommended by international heritage regulatory documents and the roles of participation in achieving the sustainable development objectives that are promoted. This study aims to fill this gap by integrating two innovative research projects to disclose what forms of participation are used to promote the acknowledged sustainability roles of participatory heritage practices.

The first project (hereafter, study 1) derives from the above-mentioned research and explores how the identified roles of participatory heritage practices in sustainable development are addressed and promoted by international heritage regulatory documents. Thirty-seven regulatory documents were extracted from a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles and book chapters on the topics of heritage, sustainability, and participation [98]. Thirteen more documents were added to the pool of documents screened for eligibility, which were published post-2015, after the issuing of the UN 2030 Agenda, by leading international organizations in the field of cultural and natural heritage management (Council of Europe (COE); Ministers of Culture of the G7; International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS); United Nations; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); UN-HABITAT; International Council of Museums (ICOM); and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)) [114]. After an initial qualitative screening of the fifty records, twenty-one documents were excluded for not mentioning both the terms heritage and sustainability in their text. This decision was taken to ensure that—whenever mentioned—participation could potentially be put in relation to both concepts. The remaining 29 records issued between 2002 and 2019 (the timeframe of the research was determined by the issuing of the UNESCO 2002′s Budapest Declaration on World Heritage, as the first heritage regulatory document explicitly mentioning both heritage and sustainability, and by the year of submission of the research paper for publication (2019)) were subject to a deductive qualitative and quantitative content analysis to identify the addressed roles of participation and trends in their promotion [114] (chapter 2).

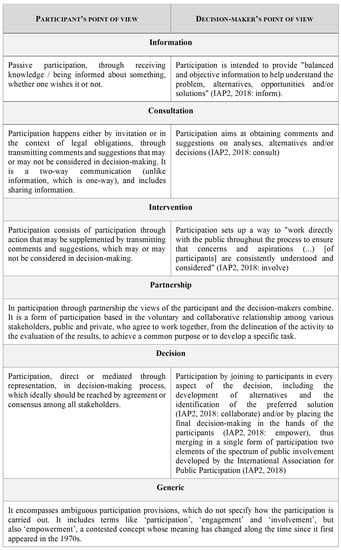

The second project (hereafter, study 2) [115] aims at understanding participation processes in the protection and safeguarding of cultural heritage, specifically in the historic urban landscape approach, within the timespan from 1970 to 2020. To achieve one of the investigation’s objectives, namely, the study of participatory dispositions in heritage regulatory documents, a sample of thirteen documents related to the UNESCO 2011 Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape [27] was considered for assessment which included the seven documents concerning heritage in the Recommendation’s Footnote 2, the 2011 Recommendation itself, a related ICOMOS document adopted the same year, and four documents posterior to 2011 that mention the Recommendation (the following 13 documents were included in study 2: 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; 1972 Recommendation concerning the Protection, at National Level, of the Cultural and Natural Heritage; 1976 Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas; 1982 ICOMOS Historic Gardens (Florence Charter); 1987 ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas (Washington Charter); 2005 ICOMOS Xi’an Declaration on the Conservation of the Setting, of Heritage Structures, Sites and Areas; 2005 Vienna Memorandum on World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture—Managing the Historic Urban Landscape; 2011 Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; 2011 Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas; 2014 Florence Declaration on Heritage and Landscape as Human Values; 2017 Delhi Declaration on Heritage and Democracy; 2017 ICOMOS and IFLA Principles Concerning Rural Landscape as Heritage; 2019 Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention.) A content analysis was performed for each document, first extracting the paragraphs mentioning any forms of participation, then analyzing all the terms and expressions used, categorizing them by reference to a set of six forms of participation—informational, consultative, interventional, partnership, decisional, or generic—attained through a literature review [116,117,118,119,120,121] and built around the Spectrum of Public Participation of the International Association for Public Participation [116] (see Figure 3). During the content analysis [122,123,124] of the excerpts of text, each term and expression was classified solely as one form of participation, thus respecting the rule of mutual exclusivity [125], leading to the construction of a Participation Thesaurus of terms and expressions used in these regulatory documents.

Figure 3.

Definitions of the forms of participation. Source: adapted from IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation, 2018 [116].

While the Thesaurus thus built is directly related to the thirteen documents analyzed, the methodology used in its production is transferable and has been validated through its application to a set of fifteen cultural heritage regulatory documents [126] (twelve documents analyzed in study 2—the 1982 ICOMOS Historic Gardens (Florence Charter) was excluded—plus the 1962 Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding of the Beauty and Character of Landscapes and Sites, the 2002 Budapest Declaration on World Heritage, and the 2015 Policy Document for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention). It can be empirically argued that a general Thesaurus concerning participation terms and expressions in heritage documents can be accomplished, and the more regulatory documents analyzed, the more accurate such a Thesaurus would become.

2. Methodology

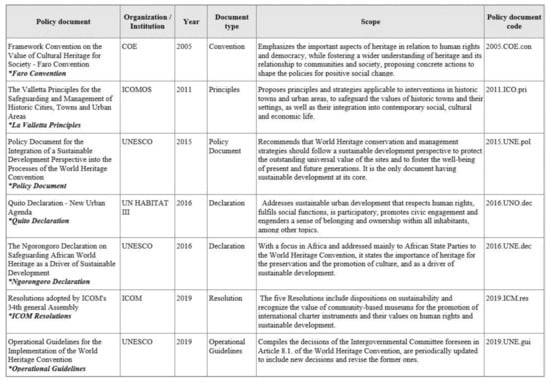

Study 1 [98,114] provided the starting point of this research for the identification of the documents to be analyzed, from which a smaller sample of documents was selected to enable comparison between the forms of participation promoted by each role. For this purpose, the exclusion/inclusion criterion was to address all three sustainability roles of participation to allow such comparison both among documents and within each individual document. As a result of this selection, seven documents were analyzed (see Figure 4), considering only those paragraphs addressing both participation and sustainable development.

Figure 4.

Selected documents. The * indicates how the document is mentioned in the text.

First, a qualitative inductive content analysis of the roles promoted by the seven selected documents enabled the identification of trends in the regulation of such roles [127] (p. 18). Then, by applying the content analysis methodology developed in study 2 [115,126], the forms of participation in the relevant paragraphs were uncovered, resulting in the identification of 49 terms and expressions that were classified according to one of the six forms of participation previously defined, leading to the construction of a Thesaurus. This Thesaurus was compared with one previously built in study 2, and both were consistently fine-tuned. Finally, both analyses were crossmatched to explore trends in the correspondences between forms and roles of participation and the influences of each document.

The documents address different topics related to heritage, such as heritage and society [26], urban heritage [29,35], world heritage, both cultural and natural [35,128,129], and museums [130]. Among the issuing organizations there are intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), which are composed of member states—like the United Nations’ programs (UN-HABITAT III) and agencies (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization—UNESCO) and the Council of Europe (COE)—and international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), which are membership-based networks of professionals, associations, civil societies and institutions, such as the International Council of Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the International Council of Museums (ICOM). The scope of these documents ranges from the introduction of new principles and recommendations on conservation and management strategies [26,29,35,128,131] to the communication of decisions and standards [129,130] (see Figure 4). Different document typologies have been used to better fulfill these purposes, which can be distinguished between those that are legally binding, such as conventions and their related operational guidelines, and those that are non-legally binding, such as principles, resolutions, policy documents, and declarations. Differences appear with respect to the legal implementation of documents of the same typology according to their issuing institutions [132,133]. The documents are either structured in articles (art.) [26], paragraphs (par.) [29,35,128,129,131], and resolutions (res.) [130], making it statistical comparisons unreliable due to the variations in their length and format. The largest document is the Operational Guidelines, with 290 numbered paragraphs, followed by the Quito Declaration, with 178 numbered paragraphs. The smallest document is the ICOM Resolutions, with only five paragraphs.

3. Results

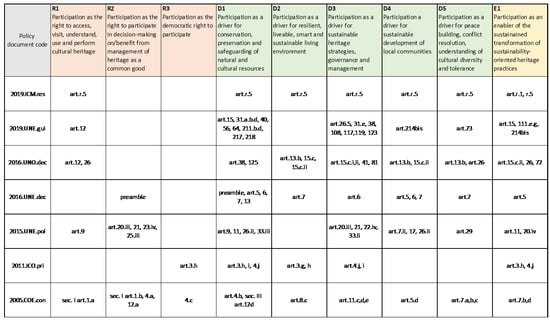

3.1. Roles of Participation

Most documents (five out of seven) address participation as a right to access, understand, choose, use, and perform culture and heritage (see Figure 5). People-centered (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.26) and community-based (ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5) approaches to heritage practices are considered inherent to the right to participate in cultural life, in line with the UN Declaration of Human Rights [44] (Faro Convention, 2005, sec. I. art.1.a; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.12, 26). All rights holders need to participate in development processes fully and meaningfully, including cultural processes (Policy Document, 2015, par.9; Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.12) without discrimination on the basis of age, ethnicity, or gender, involving all relevant stakeholders across scales, communities, and groups (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.26; Policy Document, 2015, par.9; Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.12).

Figure 5.

Analysis of articles addressing the roles of participation and their subcategories per document.

Almost half of the documents (three out of seven) mention participation as the right to participate in decision making and benefit from the management of heritage as a common good (see Figure 5). Participatory rights-based approaches apply to all phases of heritage processes, from assessing to nominating properties, managing, evaluating, and reporting (Faro Convention, 2005, art.12a; Policy Document, 2015, par.20.iii, 21). Particular attention is dedicated to ensuring the engagement of indigenous people in enlisting and development processes (Policy Document, 2015, par.21), as well as the full consent of all groups within the communities surrounding World Heritage properties over the performance of gender-rooted traditions in respect of gender equality (Policy Document, 2015, par.23.iv). Public–private partnerships are deemed necessary to the development of appropriate policies and balanced markets necessary to the respect of these rights, including the equitable distribution of benefits among all stakeholders from, in, and around World Heritage properties (Faro Convention, 2005, art.1.b, 4.a; Policy Document, 2015, par.25.iii; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, preamble).

Few documents (two out of seven) refer to participation as a democratic right (see Figure 5). Traditional systems of urban governance should embrace a participatory change by distributing information, training, and raising awareness among residents to facilitate their participation and the consequent establishment of new democratic institutions (La Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.h). Such institutions should then define the necessary restrictions to protect everyone’s rights and freedom, as well as the public interest (Faro Convention, 2005, art.4.c).

All documents address participation as a driver of conservation, preservation, and safeguarding of natural and cultural resources (see Figure 5). Natural and cultural heritage processes can be sustainably leveraged to strengthen social participation and the exercise of citizenship to promote and safeguard cultures, languages, sites and museums, the arts, and traditional knowledge, using new techniques and technologies (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.38, 125). For instance, when reconstruction is considered an adequate intervention, all concerned local communities play a critical role in ensuring the integration of new and traditional techniques (Policy Document, 2015, par.33.iii). Furthermore, intergenerational and gender-balanced engagement can facilitate not only the preservation and transmission of cultures and knowledge, but also ensure its evolution (Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, preamble). Raising public awareness of the importance to share the responsibility of heritage preservation and building communities’ capacities to safeguard and conserve it, being conscious of risks and threats, is fundamental to the establishment of international dialogues and local intersectoral and interdisciplinary cooperation for the nomination, restoration, and protection of heritage assets, world heritage, practices and the upholding of values, including the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) (ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.13; Policy Document, 2019, par.15, 40, 217, 218; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.6, 7, 13; Policy Document, par.9, 26.ii; Faro Convention, 2005, sec. III art.12.d; La Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.i). In fact, it is considered both an individual and a collective responsibility to protect everyone’s own heritage as much as others’, particularly in the context of European regulations, where all the different cultural expressions are considered the heritage of Europe (Faro Convention, 2005, art.4.b). Adequate financial measures (La Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.h; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016), governance frameworks and management systems need to be set in place to encourage the participation of all relevant stakeholders and rights holders and ensure the successful implementation of the participatory practices finalized to heritage preservation and safeguarding, as, for instance, in the development of locally driven, sustainable, and responsible tourism industries (Policy Document, 2015, par.9, 26.ii).

Nearly all documents (five out of seven) consider participation as a driver of a resilient, smart, and sustainable living environment (see Figure 5). Integrated approaches to territorial development rely on the adoption of people-centered approaches, which are inclusive, gender- and age-responsive, and supported by activities for the capacity building of stakeholders at all levels and across sectors (ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.15.c.ii). Urban development plans that are coherent and co-created by stakeholders, with the support of sound institutions and urban governance, are crucial to social inclusion and environmental protection, resulting in more accessible, inclusive, green, and safe public spaces (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.13.b). Ensuring the inclusion of heritage in these plans enables leveraging its power to foster people’s sense of belonging and responsibility towards their living environment, potentially contributing to the reinforcement of social cohesion (Faro Convention, 2005, art.8.c). International dialogue and collaboration offer important resources to address climate change, environmental degradation, and the illicit traffic of fauna and flora (Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.7), while continuous local dialogue and direct consultation with residents and other stakeholders are fundamental to the safeguarding of historic areas (La Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.g, h).

All the documents address participation as a driver of sustainable heritage strategies, governance, and management (see Figure 5). Community-inclusive organizations are considered fundamental to the promotion of organizations themselves and to the successful development and implementation of relevant regulatory tools and standards that foster a shared sense of responsibility for heritage, complementing the role of public authorities (Faro Convention, 2005, art.11.d, e; ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5; Policy Document, 2015, par.20.iii, 22.iv; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.15.c.i, ii). Advisory bodies and other competent international NGOs are also called to assist in the effective implementation of nomination processes, projects, and programs (Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.31.e, 38), while state parties, in turn, are encouraged to ensure the collaboration of all concerned stakeholders in decision making for an appropriate governance and management system that is equitable and collaborative, as a necessary condition for the sustainable conservation and management of heritage and our cities (Faro Convention, 2005, art.11.C; La Valletta Principles, 2011, par.4.j, i; Policy Document, 2015, par.20.iii, 21, Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.117, 119; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.15.c.i, ii, 41, 81). Recommendations for sustainable heritage management also include the crucial support of all development partners, ranging from the private sector to industries and finance institutions (Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.6; Policy Document, par.33.ii).

Most of the documents (six out of seven) indicate participation as a driver of sustainable development for local communities (see Figure 5). Community-based museums, through their transformative approaches, are considered to play an important role in the development of sustainable living communities, especially for the integration of cultural minorities and indigenous people in facing challenges posed by migration (ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5). Capacity-building programs and adequate policies should foster inclusive and sustainable economic benefits for local groups and communities, promoting sustainable development initiatives through heritage processes in relation to and beyond locally-driven tourism, promoting economic diversification and strengthening socio-economic resilience (Faro Convention, 2005, art.5.d; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.5, 26.ii; Operational Guidelines, par.214bis). Development partners, in turn, are called to assist in eradicating poverty and working towards the improvement of the livelihood of the people (Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.6). “The reduction of inequalities in all societies is essential to a vision of inclusive sustainable development” (Policy Document, 2015, par.7.ii); therefore, (world) heritage processes should be fully inclusive, with attention to gender equality and diversities, to tackle structural causes of inequalities, reducing exclusion and discrimination (Policy Document, 2015, par.7.ii, 17). Moreover, the promotion of civic engagement in cities and urban settlements should enhance social cohesion, political participation, and the free cultural expression of individuals (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.13.b).

Almost every document (six out of seven) mentions participation as a driver of peacebuilding, conflict resolution, mutual understanding, and tolerance (see Figure 5). International organizations, alliances, and NGOs are encouraged to act as mediators to foster cultural understanding among communities and regions, joining public authorities in encouraging reflections on the ethics of presentation of contested heritage, respecting the diversity of interpretations, developing and sharing knowledge of cultural heritage to foster mutual understanding, fighting discrimination and violence, and facilitating a peaceful coexistence, establishing processes of reconciliation and of prevention of conflicts for inclusive, safe and pluralistic societies (Faro Convention, 2005, art.7.a, b, c; ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res. 5; Quito Declaration, 2019, par.13.b, 26). For this purpose, advisory bodies should assist state parties in the diversification and harmonization of World Heritage Tentative Lists, promoting respect for cultural diversity, coexisting values, and common heritage (Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.73). State parties are also called to collaborate and cooperate in a global dialogue to address challenges faced regionally in relation to conflicts, illicit trades, and terrorism that affect communities and their heritage, recognizing the importance to adopt rights-based approaches, ensure inclusive political processes, develop effective systems of justice, and appropriate strategies and mechanisms for conflict prevention, resolution, and post-conflict recovery (Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.7; Policy Document, 2015, par.29).

All documents acknowledge participation as an enabler of sustainable development (see Figure 5). To enable the meaningful participation of individuals, groups, communities, and organizations in heritage processes, governments are encouraged to develop inclusive systems and human-centered policies, which empower the different stakeholders and coordinate their actions, and which are supported by long-term planning (Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.11.e; Ngorongoro Declaration, par.5; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.15.c.ii, 26, 72). Distributing information, raising awareness, and life-long education of stakeholders of all ages, across sectors, and at all scales, through capacity building and training programs, are deemed crucial for the sustainable adoption of inclusive people-centered approaches to integrated territorial development, heritage management, and conservation (The Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.h, 4.j; Faro Convention, 2005, art.7.b, d; Policy Document, 2015, art.11; Operational Guidelines, art.15, 111.g). These programs should be based on scientific research and local knowledge to foster engagement, innovation, and entrepreneurship, in collaboration with local institutions, such as museums, as trusted sources of knowledge and valuable resources for engaging people and empowering them to imagine, design, and create a more sustainable future for everyone (Policy Document, 2015, par.11; Operational Guidelines, par.214bis; ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.1).

3.2. Forms of Participation

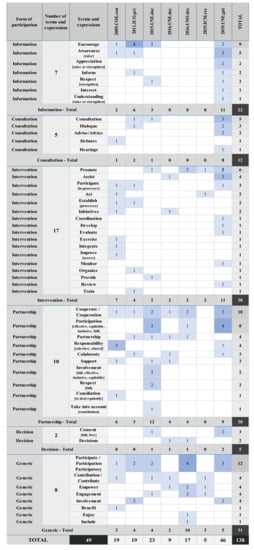

The Thesaurus constructed through the analysis of the paragraphs revealed 49 terms and expressions related to forms of participation, which were employed 138 times throughout the seven documents (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Terms and expressions and forms of participation per document.

The most mentioned form of participation is ‘Partnership’, with ten terms and expressions referenced 38 times, corresponding to 27.5% of the total. The terms ’cooperation’ (10 mentions) and ‘effective, equitable, inclusive and/or full participation’ (eight mentions) are the most used. All eight mentions appear in UN documents, namely, in the Operational Guidelines (four), the Policy Document (three), and the Quito Declaration (one) and, among those who are requested to participate, the communities (especially the local ones) take the lead with seven mentions, followed by the indigenous peoples with five mentions, four of which occur in the Operational Guidelines, the most recent document analyzed. These terms and expressions are followed by ‘partnership’ (four), used in four different documents, and ‘collective or shared responsibility’ (four), which is the form of partnership preferred in the Faro Convention (three). In absolute numbers, the UNESCO Policy Document is the one that recommends ‘partnership’ the most frequently (twelve), followed by the Operational Guidelines (nine), pointing out UNESCO’s advocacy for the establishment of partnerships in fostering sustainability-oriented World Heritage practices. The Faro Convention is the third document presenting a high incidence of these terms (six). In contrast, the ICOM Resolutions do not recommend any form of partnership for the implementation of participatory heritage practices that address the above-mentioned sustainable development objectives.

The second most mentioned forms of participation are the ‘Generic’ ones (31), encompassing eight terms and expressions, among which ’participation’-related terms are mentioned 12 times, largely surpassing the other four most used terms, namely, ‘contribution’, ‘empowerment’, ‘engagement’, and ‘involvement’, which were only used four times each. Among other generic terms, ‘benefit’ (one) is used only in the Faro Convention, while ‘enjoy’ and ‘include’ are exclusively used in the Quito Declaration, the document that uses more generic terms and expressions to recommend participation (10).

The third most recommended form of participation is ‘Intervention’ (30), with the highest number of different terms and expressions used (17). These range from ‘promote’ (six), ‘assist’ (four) and ‘participate in processes’ (three) to three other terms and expressions used only two times, and another ten used only once in all the seven documents. All documents recommend at least two forms of intervention, and the Operational Guidelines (11) and the Faro Convention (seven) are the documents that score higher.

‘Information’ is the next most recommended form of participation (22), with seven different terms and expressions, among which the terms ’encourage’ (nine) and ‘awareness’ (five) are the more used, although the first is used only in four of the documents and the second in three. The Operational Guidelines is the document that mostly recommends information as a form of participation (11), followed by The Valletta Principles (six).

The Quito Declaration, the Ngorongoro Declaration, and the ICOM Resolutions do not recommend ‘Information’ in the context of participation and sustainable development. These three documents do not recommend any form of ‘Consultation’ either, making it the second least recommended form of participation (12). Five terms are used, among which the term ‘consultation’ (five) is the most recommended, followed by ‘dialogue’ (three). Here, the Operational Guidelines present the higher results (eight), standing out from the other three documents that present much lower figures.

The least recommended form of participation is ‘Decision’, with all five mentions in the United Nations’ documents, through the expression ‘full or free consent’ (three), used by the Policy Document (one) and the Operational Guidelines (two), and the term ‘decision’ (two), used once in the Quito Declaration and the Ngorongoro Declaration.

3.3. Forms of Participation per Role

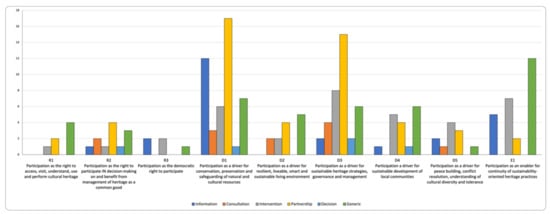

The crossed analysis of the roles of participation in addressing sustainable development and the six forms of participation, as used by the examined regulatory frameworks, highlights interesting relations between the two codings (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analysis of articles addressing the roles of participation and their subcategories per document.

3.3.1. Forms of Participation as a Right

Generic forms of participation prevail when participation is acknowledged as a right, particularly in the right to access and perform heritage and the right to take part in decision making and benefit from it. In fact, the right to benefit from and contribute to the enrichment of cultural heritage (Faro Declaration, 2005, art.4; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, preamble), as well as the enjoyment and participation of all rightsholders in their cultural life and heritage processes (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.12; Faro Convention, 2005, art.1; Policy Document, 2015, par.9; Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.12), as part of democratic systems (The Valletta Principles, 2011, art.3.h), are promoted by these documents in general terms, without offering an indication of how these forms of participation can be carried out, despite hinting to complex processes, requiring interventions at different scales, institutions, and sectors. UN-related organizations being the main promoters of these forms, this trend might be explained by the purpose of these documents, which aim to reach a vast and diverse audience, e.g., the Quito Declaration, included in the New Urban Agenda adopted during the Habitat III Conference as “a resource for every level of government, from national to local; for civil society organizations; the private sector; constituent groups; and for all who call the urban spaces of the world ‘home’ to realize this vision” (Quito Declaration, 2016, preamble). The recommendation of more specific forms of participation might impair the wide acceptance and the implementation of the agenda.

Besides generic forms, partnerships are indicated to support the regulation of participation as a right, particularly in the case of the rightful participation of heritage management and shared benefits (R2), for a more concrete enforcement of that right. An example is offered by the UNESCO 2015 Policy Document, which straightforwardly addresses sustainable development and is the main promoter of partnership forms of participation, encouraging the equitable, full, and effective participation and involvement of local communities and indigenous people in the evaluation and monitoring of World Heritage Properties (Policy Document, 2015, art.21).

On the other hand, the predominance of participation at an information level, when considered as an expression of democratic values and processes, evokes a one-way communication, excluding completely any form of decision and partnership, which does not fully correspond to the ideal of a democratic participation based on inclusion, equal representation, integrity and accountability, individual liberty, and non-violent conflict resolution [134] (p. 49). However, when the ICOMOS Valletta Principles promotes the distribution of information and awareness-raising activities in relation to democratic processes, it also recommends training initiatives (intervention) aimed to foster the participation of residents in urban governance systems and facilitate the transition towards new democratic institutions (The Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.g). Such associations of terms and related practices seem to promote both passive and active forms of participation that are functional with respect to the right to participate and its future enforcement, in support of the role of participation as an enabler of the sustained transformation of sustainability-oriented heritage practices (The Valletta Principles, 2011, art.4.j).

3.3.2. Forms of Participation as a Driver

Participation in the form of partnership dominates the advocacy for participation as a driver of conservation, preservation, and safeguarding of natural and cultural resources (D1) and of sustainable heritage strategies, governance, and management (D2). Interdisciplinary and intersectoral collaboration (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.7; Operational Guidelines, par.117; The Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.i) and cooperation (Policy Document, 2015, par.25; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.7; Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.15, 56, 64; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.15; Faro Convention, 2005, art.11; The Valletta Principles, 2011, art.3.i), through strengthened public–private partnerships, are promoted to foster the full and equitable involvement and participation of all players and the sharing of responsibilities (Policy Document, 2015, par.20, 21, 22, 25, 33; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.13; Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.64, 119, 123, 211; La Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.h; Faro Convention, 2005, art.4; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.15) in safeguarding, conserving, governing, and managing heritage. Both these subcategories are also significantly encouraged through forms of intervention and generic forms of participation, stressing a possible correspondence between active forms of participation and the achievement of those sustainable development objectives through participatory heritage practices promoted by different stakeholders.

Different stakeholders are encouraged to intervene and assist in the evaluation, monitoring, review, and implementation of programs and activities (Faro Convention, 2015, art.11; Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.31, 38), and in the promotion of the engagement of different actors and in lead organizations (ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5; Policy Document, 2015, par.33, Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.119), participating, engaging, and giving their contribution to heritage conservation and management (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.38, 41, 81, 125; The Valletta Principles, 2011, par.4.j; Policy Document, 2015; par.9, 23.iv; Ngorongoro Declaration, preamble; Operational Guidelines, 2019, art.40, 108, 123; ICOM Resolutions res.5).

Despite the low numbers, here we can also find the highest incidence of decisional forms of participation, for instance, stressing the importance of demonstrating that state parties obtained the prior, free, and informed consent of indigenous peoples in nomination processes through a transparent and public process of consultation (Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.123), and ensuring that participative decision making in urban governance, planning, and follow-up processes is realized through enhanced co-provision, co-production, and civil engagement (Quito Declaration, 2016, par.41).

On the other hand, there is a high incidence of forms of information in relation to the same two subcategories, particularly in D1—namely, the importance of informing, fostering understanding, and appreciation, and raising awareness of the importance to preserve natural and cultural heritage (Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.211, 217, 218, 219; Faro Convention, 2005, art.12)—mainly promoted by the UNESCO 2019 Operational Guidelines throughout its text in combination with other forms of participation (D1–D3: partnership, consultation, intervention, generic). Such a trend suggests that information is a crucial first step to encourage the initiatives of conservation associations, state parties, and other governmental, non-governmental, and private organizations in taking an interest in heritage management and conservation, and the participation of advisory bodies in the implementation of global strategies (The Valletta Principles, 2011, par.4; Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.40, 56), in support of more active engagement in these practices.

Generic forms of participation are significantly used to promote participation as a driver of a resilient and sustainable living environment (D2) and of the sustainable development of local communities and groups (D4), followed by forms of partnership and intervention. General statements, as mainly formulated by the Quito Declaration in the New Urban Agenda to fit different contexts, stress the importance to leverage participatory heritage practices to reduce inequalities and exclusion (Policy Document, 2015, par.7), and enhance the transformative approaches of community-based museums, ecomuseums, and urban governance towards sustainable territorial development and living communities, for green, accessible, inclusive, safe, and quality public spaces, along with inclusive, sustained and sustainable economic growth (ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5; Quito Declaration, 2016, par.15).

More defined forms of participation are mentioned in relation to specific contexts, such as in the case of the Ngorongoro Declaration, another document specifically addressing sustainable development, which considers the intervention of development partners in heritage practices to assist in the eradication of poverty in Africa, and the involvement of communities in the decision making and benefit-sharing of World Heritage processes (intervention: Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, Declaration.5).

Participation as a driver of peacebuilding, tolerance, conflict resolution, mutual understanding of diversities and tolerance (D5) is promoted by all documents, except the ICOMOS 2011 The Valletta Principles, through a balanced combination of different forms of participation. Informational and consultative forms are used to encourage reflection on ethics and methods of heritage practices (Faro Convention, 2005, art.7), require the respect of appropriate systems of conflict prevention (Policy Document, 2015, Declaration.29), and generate dialogues between communities, groups, and state parties to foster the respect of cultural diversity and common heritage, reflecting it into Tentative Lists (Operational Guidelines, 2019, Declaration.73). More active intervention and partnership forms of participation encourage heritage organizations to act as mediators for cultural understanding (ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5) and state parties to establish conciliation processes in collaboration with other competent bodies to deal in a respectful and equitable way with diversity and contrasting values, facilitate peaceful coexistence, promoting mutual understanding and trust, and prevent conflicts (Faro Convention, 2005, art.7; Quito Declaration, par.26, 13; Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.7).

3.3.3. Forms of Participation as an Enabler

Generic forms of participation dominate the acknowledgment of participation as an enabler of the continuity of sustainability-oriented heritage practices. Governmental and non-governmental organizations are encouraged to contribute to the organization of capacity-building programs and training for communities and groups and to engage with them, empowering the global society in imagining, designing, and creating a sustainable future for all (Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, par.5; ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.1, 5; Quito Declaration, 2016 par.15; The Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.j, 4.h). The UNESCO 2015 Policy Document takes a more active stand in promoting technical cooperation, policy training, capacity building, and quality education tailored to different audiences through a variety of learning environments to ensure effective rights-based approaches (Policy Document, 2015, par.11, 20). These practices are then also promoted through interventional forms of participation via following documents or other organizations, by encouraging the development of educational and capacity-building programs in combination with mechanisms for the sustained involvement and coordination of different activities of multiple stakeholders (Operational Guidelines, 2019, par.111, 214bis; Faro Convention, 2005, art.7; ICOM Resolutions, 2019, res.5; The Valletta Principles, 2011, par.3.h).

3.4. Trends

Generic and interventional forms of participation are the only ones used to promote all roles and subcategories. Together with partnership, which is not used exclusively in relation to participation as a democratic right (R3), they are the most used forms of participation in the documents. Therefore, active forms of participation appear as the ones most promoted by the analyzed international heritage regulatory frameworks in relation to participatory heritage practices and sustainable development objectives.

These active forms include generic forms of participation, which can be recommended to a variety of stakeholders in different contexts, across sectors, and at different scales, which then need to be interpreted and adapted according to local realities. However, the widespread low presence of forms of decision raises doubts over the generally encouraged nature of the partnerships and interventions promoted, suggesting an increasing willingness to implement the effective, inclusive, and equitable involvement of different stakeholders, but reluctance in recommending sharing the power attached to decision making.

Generic forms can also mainly be found in relation to participation as a right and as an enabler. On the one hand, these forms can help to grasp the wide spectrum of participation which fits into everyone’s right to take part in and access heritage, physically and intellectually. On the other hand, generic forms seem the most preferred when addressing the need to create the conditions that enable participation both in current and in future practices, such as through training, education, capacity building, and long-term planning. While fitting the purpose of creating a vision for future practices, these forms of participation omit to concretely define how to achieve that vision and require complementation with other more explicit forms of participation.

Similarities can be observed between the forms used to promote participation as a driver of heritage conservation, preservation, and safeguarding (D1), of sustainable heritage strategies, management, and governance (D3), between forms of participation as a driver of resilient and sustainable living environments (D2), and of the sustainable development of local communities (D4), as they are often promoted together, hinting at stronger interrelations between these sustainable development objectives in the context of participatory heritage practices.

Decisional forms of participation are only used when addressing participation as the right to participate in decision making and benefits (R2) and related subcategories of participation as a driver, such as participation for sustainable heritage management and governance (D3), for the preservation and safeguarding of heritage (D1), and for the sustainable development of local communities (D4).

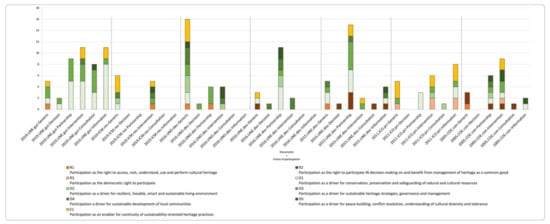

3.5. Influences

The UNESCO 2015 Policy Document and the 2019 Operational Guidelines are the only two documents using all forms of participation (see Figure 8). However, while in absolute numbers the latter seems to dedicate more space to the promotion of a variety of active forms of participation as a driver of heritage conservation and safeguarding (D1) and sustainable heritage management and governance (D3), it dedicates less attention to the acknowledgment of participation as a right, omitting to mention participation as the right to take part in decision making and attain benefits from heritage processes (R2), which are strongly linked to the effective implementation of participation as a driver, particularly in the case of D3 and D1, as shown by the previously identified trends.

Figure 8.

Analysis of articles addressing the roles of participation and their subcategories per document.

On the other hand, the 2015 Policy Document uses significantly more partnership forms of participation to promote all three roles of participatory heritage practices, in line with the United Nation 2030 Agenda—referenced by and the source of inspiration for this document—which acknowledges partnerships both as one of the five leading principles of the agenda (the ‘5 Ps’: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership) and one of the seventeen goals (SDG 17 ’Partnership for the Goals’) [17]. Besides its focus on partnership, the 2015 Policy Document uses all forms of participation to promote each role, nevertheless, avoiding the use of general forms to encourage the implementation of participation as an enabler of the continuity of sustainability-oriented heritage practices, pushing for the adoption of concrete solutions to foster the sustained and integrated participatory and sustainability-oriented practices in heritage processes.

The Council of Europe’s Faro Convention is the only document addressing all roles of participation and their subcategories and uses a variety of forms of participation, favoring active forms, such as intervention and partnership, to promote all of them, failing, however, to include decisional forms. On the other hand, the ICOMOS Valletta Principles is the document promoting the fewest participation roles subcategories, adopting a similar approach to the Faro Convention, using a balanced variety of forms of participation as complementary, including informational, interventional, and generic forms.

The UNESCO Ngorongoro Declaration and the UN-HABITAT III Quito Declaration take a distance from balanced approaches and respectively strongly promote partnership and generic forms of participation. On the one hand, the Ngorongoro Declaration mainly promotes active partnerships for the implementation of participatory heritage practices that are drivers of multiple sustainable development objectives, leaving the use of generic forms to the promotion of participation as a right and as an enabler. It advocates “Africa’s unique context” and addresses region-specific concerns related to “socio-economic development and peace using cultural and natural heritage resources as a catalyst” (Ngorongoro Declaration, 2016, preamble), acknowledging international and local partnerships as a fundamental approach to achieve these goals.

On the other hand, the Quito Declaration predominantly uses generic forms of participation to promote all roles and their subcategories, in addition to a few mentions of intervention, partnership, and decisional forms. This choice could be bound to the need of these documents to address and inspire the practices of a variety of stakeholders, from governmental to non-governmental and private organizations, at different scales and across sectors. The same could explain the use of generic forms in UNESCO policies, conventions, and guidelines, which need to be adopted and implemented by state parties worldwide with different cultures and legislations. Conversely, the regional character of documents like the Ngorongoro Declaration (Africa) and the Faro Convention (Europe) could affect their choice in using more specific forms of participation to promote their roles in addressing sustainable development objectives in contexts that partially share similar cultural and legal affecting factors. In support of this assumption, the Faro Convention and the Valletta Principles are the only two documents addressing participation as a democratic right, also using interventional forms of participation to promote it, in line with the Council of Europe’s mission statement—“The Council of Europe seeks to develop throughout Europe common and democratic principles based on the European Convention on Human Rights” [80]—and suggesting a still western-based character of ICOMOS. However, the lack of decisional forms of participation in both these documents testifies to a still diffused traditional approach to heritage processes in European countries, in which different stakeholders, communities, groups, and individuals are welcome to participate, but decisions are apparently still taken by authorities and experts [115].

Eventually, the ICOM Resolutions exclusively uses intervention and generic forms to promote all the addressed roles of participation and their subcategories, placing this document across the two identified approaches to influence. On the one hand, the sector-specific character of this document, which offers recommendations on museum practices, could explain the specific forms of intervention that are used, similarly to what is observed in the ICOMOS Valletta Principles. On the other hand, the very nature of its issuing organization, which addresses an international network of museums, professionals, and institutions, could justify the significant use of generic terms to reach a vast and diverse audience from different geographic areas.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This exploratory research of seven documents from different organizations proposes a novel method to better understand how participation is promoted by international heritage regulatory frameworks that directly or indirectly address heritage practices with reference to sustainability. To the best of our knowledge, it represents a first attempt to relate the recommended forms of participation by international heritage regulatory documents and the roles that participatory heritage practices can play in achieving sustainable development objectives. Therefore, this research has contributed to further developing the understanding of the promoted quality of participatory heritage practices that determines which roles participation can play (as a right, as a driver, and as an enabler) in achieving sustainable development objectives, as theorized by recent research [98]. Particularly, it has generated new knowledge of the variety of forms of participation recommended by regulatory documents, the trends of those regulations, their influences, and the potential implications for sustainable development objectives that their adoption and implementation can have.

The study reveals that generic, interventional, and partnership are the most used forms of participation, making active forms those most used to promote all the roles and subcategories of participation in addressing sustainable development. This trend is in line with the increased advocacy for more active and inclusive governance models [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78], which is reflected in the emergence of theorization about and widespread attempts to implement people-centered approaches in heritage processes [2,22]. However, while much case studies-based research focuses on the engagement of communities, groups, and individuals, advocating their active participation throughout the heritage processes [99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,109,110,111,112,113], this research argues that there is no necessary hierarchy among passive and active forms of participation, which are mutually complementary at different stages of sustainability-oriented heritage practices. This conclusion contributes to the criticism of the idea of a ‘ladder of participation’ or the outline of levels of participation that attributes a negative connotation to more passive steps, such as information and consultation. The limitations of hierarchical models, however, has been underlined since its introduction, not only because it is not always possible to establish clear boundaries among the different levels of participation, but also because it considers participants as homogenous groups of people, detached from their socio-cultural and economic environments, needs, and expectations [117,118,119,120]. In fact, as pointed out by Wilcox [118] (p. 8), “different levels are appropriate in different circumstances” and results show that all levels are functional when adequately integrated into sustainability-oriented participatory heritage practices—hence the adoption of the more neutral expression ‘forms of participation’.

While generic forms are mostly chosen when addressing a diverse and international audience, such as in the case of the UN-HABITAT III Quito Declaration, the UNESCO Policy Document, and the Operational Guidelines, partnership and intervention are preferred at regional and local scales, as in the UNESCO Ngorongoro Declaration and the Council of Europe Faro Convention. Nevertheless, the combination of these trends with a generally low incidence of decisional forms of participation suggests a willingness to implement more inclusive heritage practices accompanied by the resistance to ultimately share decisional power, raising doubts over the wished partnerships and the character of the promoted democratic processes. This acknowledgment contributes to what has been increasingly researched, particularly within critical heritage studies, concerning the complexity of addressing and untangling the power dynamics that at multiple scales reinforce an ‘authorized heritage discourse’ [86,87,88,89,90,91]. Results show that a more participatory governance is wished and encouraged by international heritage organizations, heterogeneously but unanimously, in line with the theorizations of governance models in place since the 1970s, which see the participation of multiple stakeholders who share responsibilities and are accordingly held accountable [65,66,67,68,69]. However, the encouragement of more deliberative models of governance that emerged in the 1980s, entailing the facilitation of reciprocal exchanges among actors who debate and negotiate common solutions [74], seems to be more challenging. Indeed, decisional forms of participation are only used once by the UNESCO 2015 Policy Document to promote the right to participate in decision making and benefits (R2), and once by the Ngorongoro Declaration and in the Quito Declaration when addressing those subcategories of participation as a driver that relate to the benefits that participatory practices can bring to heritage management and governance (D3), the conservation and safeguarding of heritage (D1), and local communities (D4). This limited integration might be explained by the slow-paced influence of research on regulations, as well as by the political implications of sharing power [88,89,90,91]. Anyhow, the current, limited regulation for a shared allocation of decision-making power among involved parties might not fully help to address those challenges related to the implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of more deliberative processes, without, however, necessarily preventing them.

This study did not focus on which parties and actors are recommended to participate in sustainability-oriented heritage processes by international heritage regulatory documents and how these regulations affected practices in the field. However, it created a basis to expand the scope of future research, on the one hand, to the analysis of which stakeholders are acknowledged in international heritage regulatory documents, looking at their promoted roles and responsibilities, and, on the other hand, to the adoption and adaptation of these regulations in national policies, looking at how they eventually affect place-specific participatory dynamics and how they affect the achievement of sustainable development goals. Nevertheless, it is also important to consider the long-term effectiveness of policies, the implementation of which is an ongoing process that can be observed, monitored, and researched.

Correspondences between certain subcategories of the roles of participation and related sustainable development objectives have been identified by observing similarities in the ways forms of participation are promoted. An example is offered by the relation between the encouragement of partnerships to ensure the right of all relevant stakeholders to participate in decision making and benefits, the effective implementation of participatory heritage practices as a driver of heritage conservation and safeguarding, and of sustainable heritage management and governance. It reinforces the advocated relation between inclusive and equitable approaches to heritage practices and their sustained management and conservation solutions [98,110,111,112,113]. Moreover, most of the analyzed documents also stress a direct linkage between the implementation of participatory heritage practices for a more resilient and sustainable living environment and for the sustainable development of local communities with generic, interventional, and partnership forms of participation. It emphasizes that the inclusive and equitable development of local communities is a necessary integrated factor for sustainable urban, peri-urban, and rural development [110,111,112,113]. Lastly, generic forms of participation seemed also to be preferred for the promotion of participation as a right and as an enabler, fitting the purpose of creating a vision for future practices, without concrete definitions of how to achieve that vision being given, however, and require complementation with other more explicit forms of participation. This ambiguity is in line with the critique of the evolution of the concept of empowerment that lately sees the increased use of the term as detached from the associated tensions, conflicts, and political implications of the processes of empowerment, from both an opportunity and a capacity perspective [81].

Although this research reveals existing trends pertaining to correspondences between certain roles and forms of participation, additional research is needed to further validate and develop these observations through the analysis of more documents of the same or other organizations, examining their cross-fertilization and influence in promoting forms and roles of participation. Some key documents that play an important role in advancing heritage policies and practices that encourage participation and sustainable development were analyzed in either the original study 1 and/or 2 but were not included in this analysis according to the chosen selection criteria. Some examples are the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) [27], the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage [24] (art.15), and its Operational Directives [135] (art.170–171) [136], among others.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R., C.B.C., A.P.R., M.J. and R.A.; methodology, I.R., C.B.C., A.P.R., M.J. and R.A.; validation, I.R. and C.B.C.; formal analysis, I.R. and C.B.C.; investigation, I.R. and C.B.C.; resources, A.P.R., M.J. and R.A.; data curation, I.R. and C.B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.R. and C.B.C.; writing—review and editing, A.P.R., M.J. and R.A.; visualization, I.R. and C.B.C.; supervision, A.P.R., M.J. and R.A.; project administration, I.R. and C.B.C.; funding acquisition, A.P.R. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external dedicated funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be consulted in a publicly archived dataset generated during the study. The dataset can be found at this link: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Bp-uGouzQU-YaaDEqVUY0K2tZR4-pDYa/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=115924808427033392963&rtpof=true&sd=true (accessed on 29 September 2021).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and periodical feedback of our research groups—Heritage and Values chair (HEVA, Delft University of Technology), Antwerp Cultural Heritage Sciences (ARCHES, University of Antwerp—who have recognized the potential of collaborating and merging the methodological approach of the doctoral research of Ilaria Rosetti and Clara Bertrand Cabral into this study). We acknowledge the valuable contribution of fellow researchers Ana Tarrafa Pereira da Silva and Nan Bai for the validation of the Participation Thesaurus, and of Pedro Bertrand Cabral for the technical support. Lastly, we thank the TU Delft University Library for the financial support allowing this article to be made an open access publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COE | Council of Europe |

| HUL | UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape |

| ICOM | International Council of Museums |

| ICOMOS | International Council of Monuments and Sites |

| IGOs | Intergovernmental organizations |

| INGOs | International non-governmental organizations |

| UN | United Nations |

| UN-Habitat | United Nations program working towards a better urban future |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

References

- De Cuellar, J.P. Our Creative Diversity: Report of the World Commission on Culture and Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1996; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000101651 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Labadi, S. Historical, theoretical and international considerations on culture, heritage and (sustainable) development. In World Heritage and Sustainable Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burford, G.; Hoover, E.; Velasco, I.; Janoušková, S.; Jimenez, A.; Piggot, G.; Podger, D.; Harder, M.K. Bringing the “missing pillar” into sustainable development goals: Towards intersubjective values-based indicators. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3035–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunes, N.; Sderström, H.; Hipke, S. Understanding Cultural Sustainability: Connecting Sustainability and Culture. In Culture in Sustainability: Towards a Transdisciplinary Approach; SoPhi-University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2017; pp. 29–45. Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/56075/978-951-39-7267-7.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNCED. AGENDA 21. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), Earth Summit, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- United Nations. United Nations Millennium Declaration. U. Nations (Ed.) 2000. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_55_2.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- United Nations. The Future We Want. 2012. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_66_288.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Ruigrok, I. Culture, Local Governments and Millennium Development Goals 2; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- United Cities and Local Governments. Culture: Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development. 2010. Available online: https://www.agenda21culture.net/sites/default/files/files/documents/en/zz_culture4pillarsd_eng.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. The Hangzhou Declaration: Placing culture at the heart of sustainable development. In Proceedings of the Policies International Congress “Culture: Key to Sustainable Development; Hangzhou, China, 15–17 May 2013, Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/images/FinalHangzhouDeclaration20130517.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. The UNESCO Culture for Development Indicators: Implementation Toolkit. 2014. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232374 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Soini, K.; Birkeland, I. Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 2014, 51, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessein, J.; Soini, K.; Fairclough, G.; Horlings, L.; Battaglini, E.; Birkeland, I.; Duxbury, N.; De Beukelaer, C.; Matejic’, J.; Stylianou-Lambert, T.; et al. Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development: Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability; University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2015; Available online: http://www.culturalsustainability.eu/conclusions.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- United Nations. Culture and Development. 2010. Available online: https://undocs.org/pdf?symbol=en/A/RES/72/229 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Culture: A Driver and an Enabler of Sustainable Development; Thematic Think Piece: Paris, France, 2012; Available online: https://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Think%20Pieces/2_culture.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Labadi, S.; Giliberto, F.; Rosetti, I.; Shetabi, L.; Yildirim, E. Heritage and the sustainable development goals: Policy guidance for heritage and development actors. Herit. Sustain. Dev. Goals Policy Guid. Herit. Dev. Act. 2021, 1, 1–69. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Secretariat/2021/SDG/ICOMOS_SDGs_Policy_Guidance_2021.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- ICOMOS. Declaration of San Antonio. 1996. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/188-the-declaration-of-san-antonio (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- ICOMOS. The Stockholm Declaration: Declaration of ICOMOS Marking the 50th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1998. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/research_resources/charters/charter67.html (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Report of the World Heritage Global Strategy Natural and Cultural Heritage Expert Meeting; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1998; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/amsterdam98.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Labadi, S.; Logan, W. Urban heritage, development, and sustainability: International frameworks, national and local governance; International Frameworks, National and Local Governance. In Urban Heritage, Development and Sustainability; Taylor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Budapest Declaration on World Heritage. 2002. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2002/whc-02-conf202-25e.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. 2003. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/15164-EN.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. 2005. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/creativity/sites/creativity/files/passeport-convention2005-web2.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society—Faro Convention. 2005. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/culture-and-heritage/faro-convention (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. 2011. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- UNESCO. Vienna Memorandum. World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture—Managing the Historic Urban Landscape. 2005. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/5965 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- ICOMOS. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns, and Urban Areas. 2011. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/Paris2011/GA2011_CIVVIH_text_EN_FR_final_20120110.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2021).