Who Uses Virtual Wardrobes? Investigating the Role of Consumer Traits in the Intention to Adopt Virtual Wardrobes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

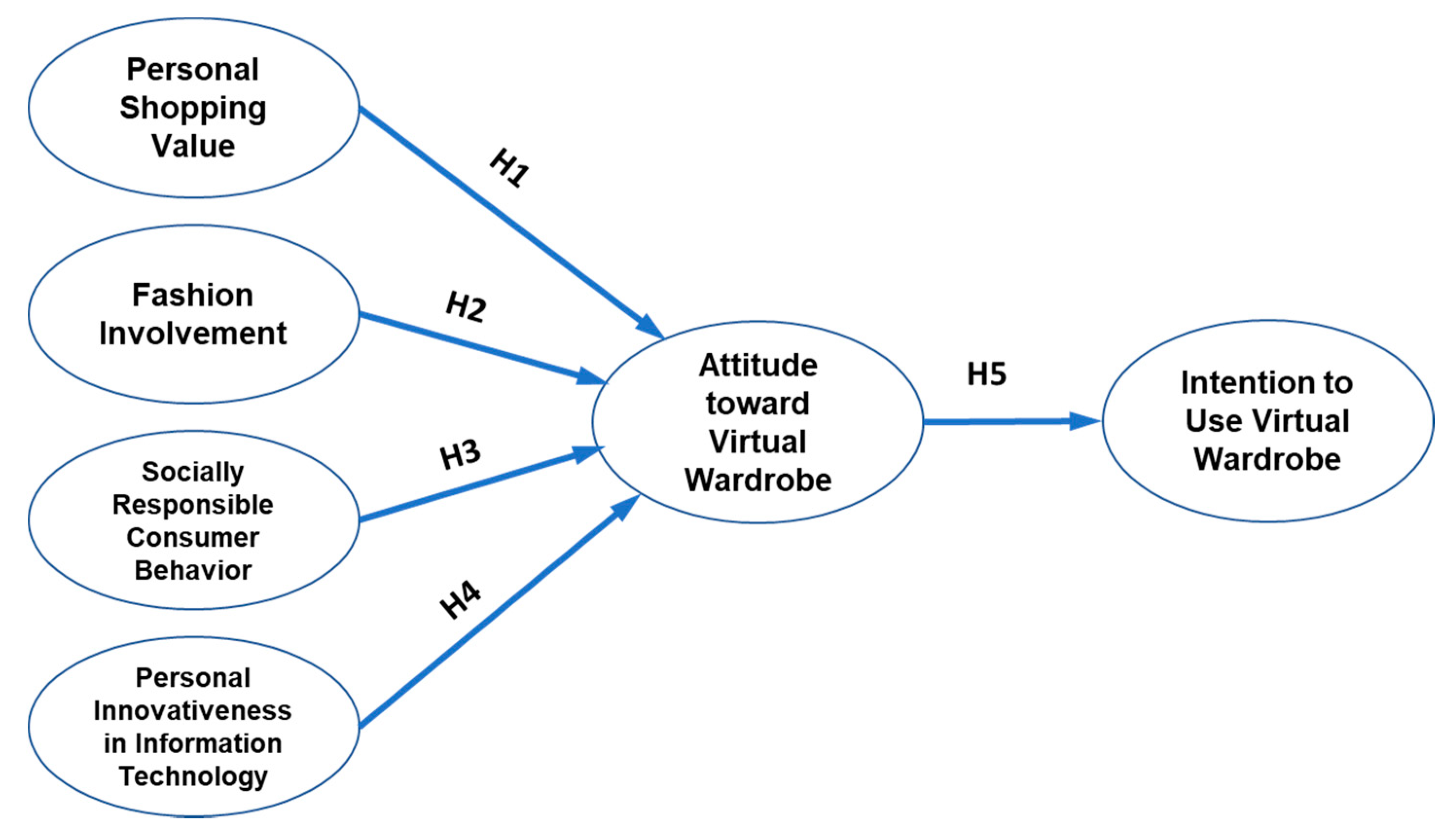

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Related Work and Rationale for Research

2.2. Personal Shopping Value

2.3. Fashion Involvement

2.4. Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior

2.5. Personal Innovativeness in Information Technology

2.6. Attitude and Behavioral Intention

3. Research Methods

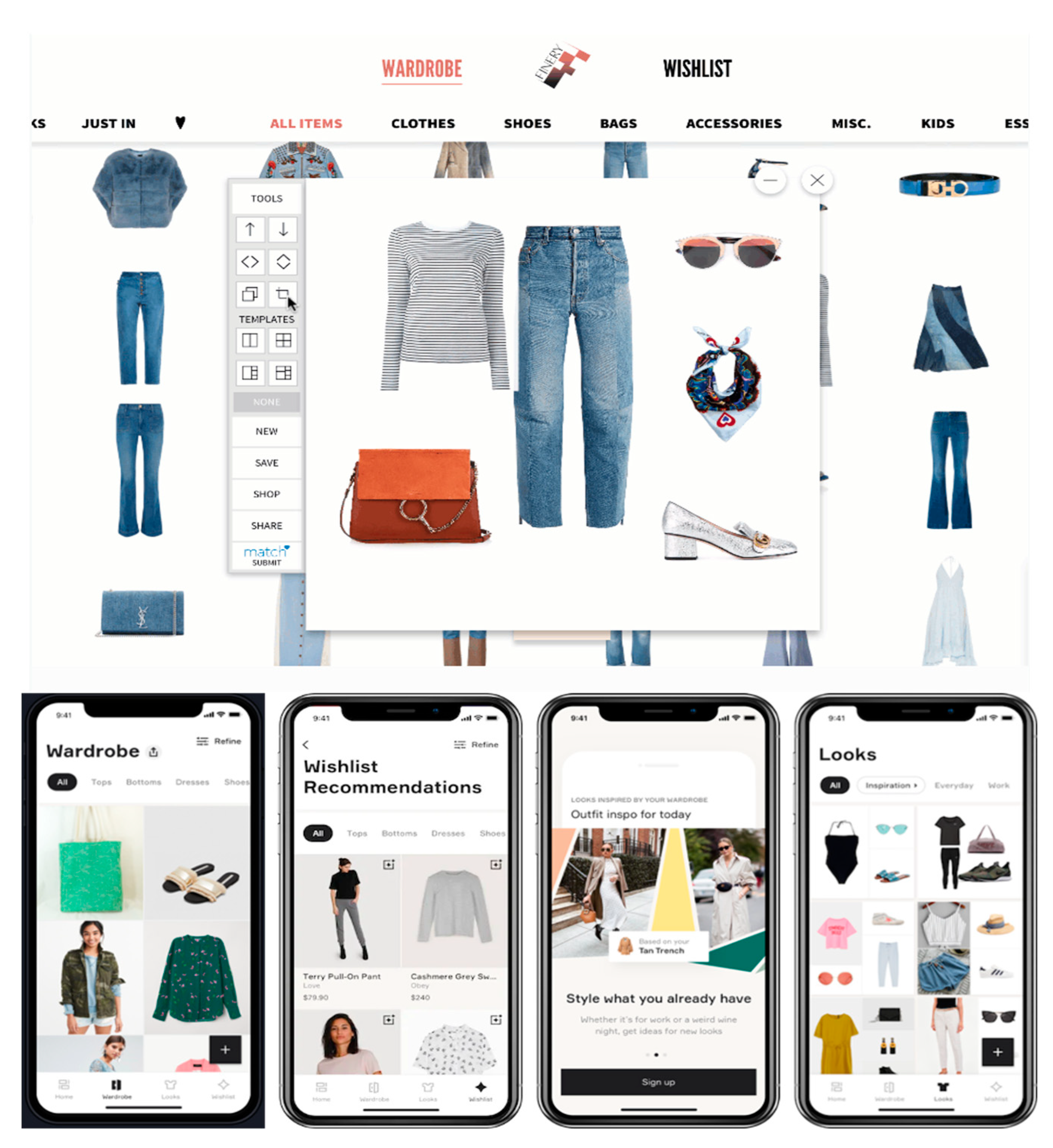

“A virtual/digital wardrobe service, which is the main topic of this research, provides convenience by transforming the user’s actual wardrobe to a virtual system. It helps users to organize the clothing items in their wardrobes by various category options. Based on the analysis of frequently visited websites and clothing purchase receipts from email, the app provides various useful information. It allows users to create a personal wish list, inform sale/promotion, and suggest clothing items which should be needed for their wardrobes. It also recommends various styling ideas based on clothes they already have and influencing factors analyzed by users’ social network service, i.e., Instagram. In addition to that, it helps users to dress comfortably for the climate and the occasion.”

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of the Measurement Model

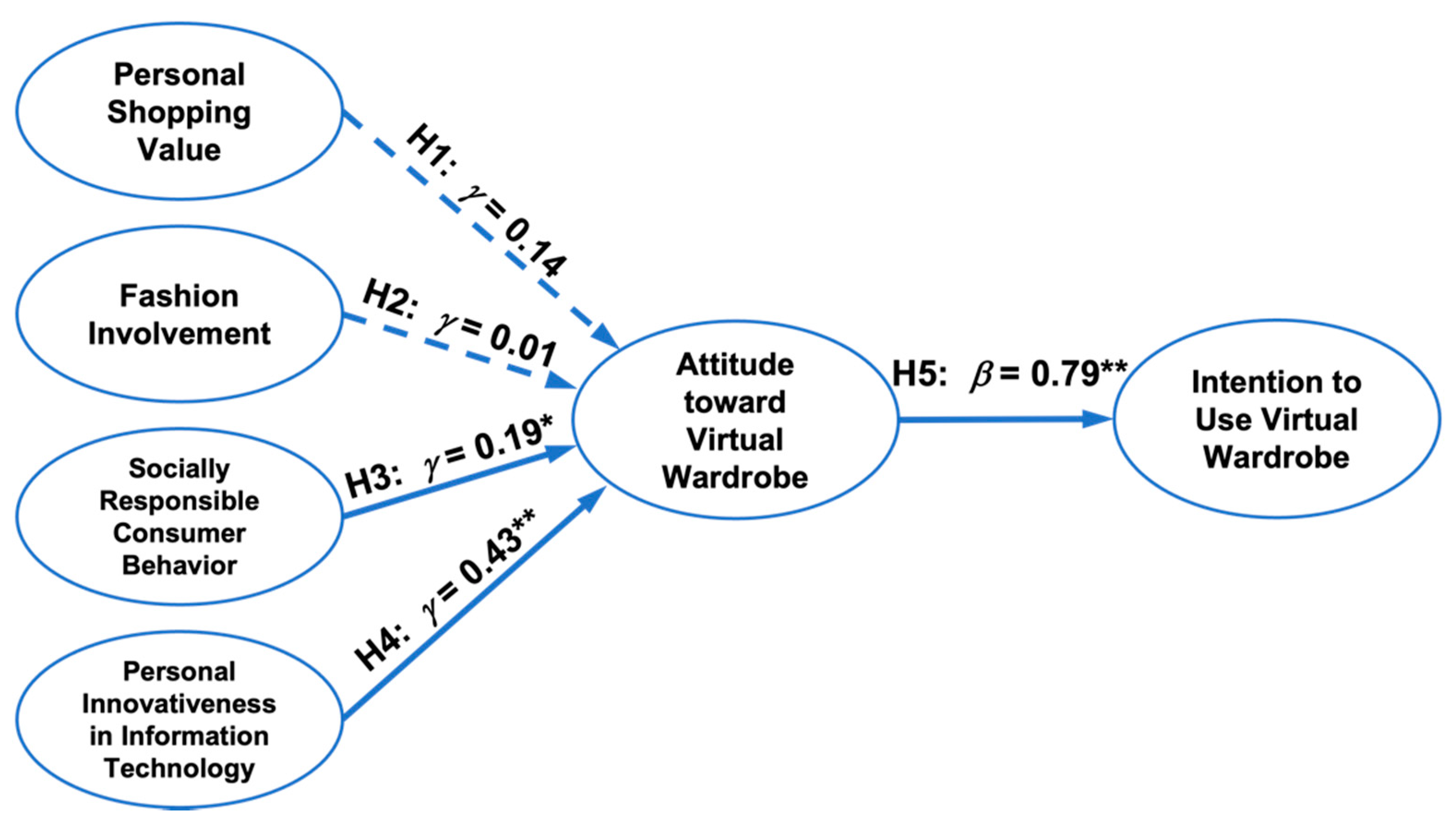

4.2. The Results of Testing the Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gwozdz, W.; Steensen Nielsen, K.; Müller, T. An Environmental Perspective on Clothing Consumption: Consumer Segments and Their Behavioral Patterns. Sustainability 2017, 9, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Closetmaid. Survey: Women’s Closets Are Full to the Brim. 2020. Available online: https://blog.closetmaid.com/2016/05/full-to-the-brim (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Tighe, D. Average Number of Clothing Products Women in the United States Have in Their Wardrobe and Don’t Wear, as of January 2017. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/789475/clothes-women-don-t-wear/ (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Bye, E.; McKinney, E. Sizing up the Wardrobe—Why We Keep Clothes That Do Not Fit. Fash. Theory 2007, 11, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, M.; Nakatani, Y. Clothes recommend themselves: A new approach to a fashion coordinate support system. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering and Computer Science, San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–21 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, K.N.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lin, E.S. Developing a smart wardrobe system. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Consumer Communications and Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–12 January 2011; pp. 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Omar, N.N.; Al-Rashed, N.M.; Al-Fantoukh, H.I.; Al-Osaimi, R.M.; Al-Dayel, A.-H.A.; Mostefai, S. The design and development of a web-based virtual closet: The smart closet project. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2013, 1, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Hu, W. The Conceptual Design of “Smart Closet” Fashion Consultant Expert System. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Rode, J.A.; Magee, R.; Sebastian, M.; Black, A.; Yudell, R.; Gibran, A.; McDonald, N.; Zimmerman, J. Rethinking the smart closet as an opportunity to enhance the social currency of clothing. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 5–8 September 2012; pp. 183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Etebari, D. Intelligent Wardrobe: Using Mobile Devices, Recommender Systems and Social Networks to Advise on Clothing Choice. Master’s Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W. Investigation of Chinese Consumers’ Adoption Intention toward E-Wardrobe: A Psychological Need and Motivational Approach. Master’s Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, A. Consumers’ acceptance of smart virtual closets. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, D.; Duffy, K. Save Your Wardrobe: Digitalising Sustainable Consumption: Further Insights; University of Glasgow: Glasgow, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, A.P. Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2003, 7, 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klobas, J.E. Beyond information quality: Fitness for purpose and electronic information resource use. J. Inf. Sci. 1995, 21, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondan-Cataluña, F.J.; Arenas-Gaitán, J.; Ramírez-Correa, P.E. A comparison of the different versions of popular technology acceptance models. Kybernetes 2015, 44, 788–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-W.; Wang, Y.-B.; Yen, N.Y. Does environmental sustainability play a role in the adoption of smart card technology at universities in Taiwan: An integration of TAM and TRA. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10994–11009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shankar, V.; Kalyanam, K.; Setia, P.; Golmohammadi, A.; Tirunillai, S.; Douglass, T.; Hennessey, J.; Bull, J.S.; Waddoups, R. How Technology Is Changing Retail. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Dabija, D.-C.; Gazzola, P.; Cegarro-Navarro, J.G.; Buzzi, T. Before and after the outbreak of COVID-19: Linking fashion companies’ corporate social responsibility approach to consumers’ demand for sustainable products. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noris, A.; Nobile, T.H.; Kalbaska, N.; Cantoni, L. Digital Fashion: A systematic literature review. A perspective on marketing and communication. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2021, 12, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, D. Magic Wardrobe: Situated Shopping from Your Own Bedroom. Pers. Technol. 2000, 4, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifeng, H.; Yuzhe, C.; Jingping, S.; Zhaomu, H. Smart Wardrobe System Based on Android Platform. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data Analysis (ICCCBDA), Chendu, China, 5–7 July 2016; pp. 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, J.; Dalmia, A.; Desai, J.; Amrutia, H. Smart Wardrobe—IoT Based Application. IRJET 2019, 6, 3699–3702. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption: Exploring the Consumer “Attitude—Behavioral Intention” Gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics. 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumer Value: A Framework for Analysis and Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dubinsky, A.J. A conceptual model of perceived customer value in e-commerce: A preliminary investigation. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential value: Conceptualization, measurement and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environment. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Hodges, N. Consumer shopping value: An investigation of shopping trip value, in-store shopping value and retail format. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahtola, O.T. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Market. Lett. 1991, 2, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilhan, D. Customer Value Co-Creation Behavior in the Online Platform Economy. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2019, 7, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Cass, A. Fashion clothing consumption: Antecedents and consequences of fashion clothing involvement. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kim, J.-H. Luxury fashion consumption in China: Factors affecting attitude and purchase intent. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. The Impact of Body Image Self-Discrepancy on Body Dissatisfaction, Fashion Involvement, Concerns with Fit and Size of Garments, and Loyalty Intentions in Online Apparel Shopping. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sproles, G.B.; King, C.W. The Consumer Fashion Change Agent: A Theoretical Conceptualization and Empirical Identification; Institute for Research in the Behavioral, Economic, and Management Sciences; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. Message framing and interpersonal orientation at cultural and individual levels. Int. J. Advert. 2010, 29, 765–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Workman, J.E. Implementation of artificial intelligence in fashion: Are consumers ready? Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2020, 38, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, H.; Kocaman, R. Roles of self-monitoring, fashion involvement and technology readiness in an individual’s propensity to use mobile shopping. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2017, 19, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Rodríguez, M.L.; Salgado-Cacho, J.M.; Moreno-Jiménez, P. What impacts socially responsible consumption? Sustainability 2021, 13, 4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Profiling levels of socially responsible consumer behavior: A cluster analytic approach and its implications for marketing. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1995, 3, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winakor, G. The process of clothing consumption. J. Home Econ. 1969, 61, 629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.E.; Hodges, N.N. Socially responsible consumer behavior?: Exploring used clothing donation behavior. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2009, 27, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fagan, M.; Kilmon, C.; Pandey, V. Exploring the adoption of a virtual reality simulation. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Are personal innovativeness and social influence critical to continue with mobile commerce? Internet Res. 2014, 24, 134–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, R.; Prasad, J. A conceptual and operational Definition of personal innovativeness in the domain of information technology. Inf. Syst. Res. 1998, 9, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yao, J.E.; Yu, C.-S. Personal innovativeness, social influences and adoption of wireless Internet services via mobile technology. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Popescu, G.H. Will the COVID-19 Pandemic Lead to Long-Term Consumer Perceptions, Behavioral Intentions, and Acquisition Decisions? Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2021, 16, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydell, L.; Kučera, J. Cognitive Attitudes, Behavioral Choices, and Purchasing Habits during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2021, 9, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracín, B.T.J.D., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- O’Cass, A. An assessment of consumers product, purchase decision, advertising and consumption involvement in fashion clothing. J. Econ. Psychol. 2000, 21, 545–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, S.H. Attitudes toward Socially Responsible Consumption: Development and Validation of A Scale and Investigation of Relationships to Clothing Acquisition and Discard Behaviors. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: Hampshire, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Short, S.W.; Rana, P.; Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nobile, T.H.; Noris, A.; Kalbaska, N.; Cantoni, L. A review of digital fashion research: Before and beyond communication and marketing. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2021, 14, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; Bagozzi, R.P. An attitudinal model of technology-based self-service: Moderating effects of consumer traits and situational factors. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs and Items | Standardized Factor Loading | t-Value | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Shopping Value (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.801) | 0.81 | 0.59 | ||

| V1—Shopping is helpful to learn information about the current fashion style. | 0.82 | 14.91 | ||

| V2—Shopping helps me to find clothing that is suitable for me. | 0.82 | 15.00 | ||

| V3—Shopping is helpful to gain information on how to coordinate clothes. | 0.66 | 11.18 | ||

| Fashion Involvement (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.762) | 0.80 | 0.57 | ||

| V4—Clothing is important to me. | 0.89 | 16.36 | ||

| V5—I consider what to wear every day. | 0.68 | 11.60 | ||

| V6—I am fashion-conscious. | 0.68 | 11.64 | ||

| Socially Responsible Consumer Behavior (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.778) | 0.80 | 0.58 | ||

| V7—I think the preservation of resources should be considered in clothing consumption. | 0.84 | 15.00 | ||

| V8—I think resource conservation and clothing consumption are related. | 0.84 | 15.01 | ||

| V9—Discarded clothing adds to our pollution problem. | 0.56 | 9.18 | ||

| Personal Innovativeness in Information Technology (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.804) | 0.83 | 0.63 | ||

| V10—I prefer products that feature leading-edge technology. | 0.51 | 8.54 | ||

| V11—People often ask me for advice on new technology. | 0.88 | 16.31 | ||

| V12—Mostly, I am the first to adopt the latest technology among people around me. | 0.92 | 17.48 | ||

| Attitude toward Virtual Wardrobes (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.889) | 0.89 | 0.73 | ||

| V13—I think using virtual wardrobe services is (would be) a good idea. | 0.83 | 16.06 | ||

| V14—I think using virtual wardrobe services is beneficial to my wardrobe organization. | 0.88 | 17.61 | ||

| V15—I think using virtual wardrobe services would help improve my clothing consumption habits. | 0.86 | 16.87 | ||

| Intention to Use Virtual Wardrobes (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.934) | 0.93 | 0.82 | ||

| V16—I intend to use virtual wardrobe services. | 0.93 | 19.78 | ||

| V17—I will try to use virtual wardrobe services. | 0.89 | 18.35 | ||

| V18—I plan to use virtual wardrobe services in the future. | 0.90 | 18.84 |

| Fit Indices | Value |

|---|---|

| Chi-Square/Degree of Freedom | 1.82 |

| Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.056 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.93 |

| Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) | 0.96 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.96 |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.92 |

| CR | AVE | PSV | FI | SRCB | PIIT | ATT | INT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSV | 0.81 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.35 |

| FI | 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.38 |

| SRCB | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.31 |

| PIIT | 0.83 | 0.63 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.59 |

| ATT | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.85 | 0.84 |

| INT | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 0.91 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bang, H.; Su, J. Who Uses Virtual Wardrobes? Investigating the Role of Consumer Traits in the Intention to Adopt Virtual Wardrobes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031209

Bang H, Su J. Who Uses Virtual Wardrobes? Investigating the Role of Consumer Traits in the Intention to Adopt Virtual Wardrobes. Sustainability. 2022; 14(3):1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031209

Chicago/Turabian StyleBang, Haeun, and Jin Su. 2022. "Who Uses Virtual Wardrobes? Investigating the Role of Consumer Traits in the Intention to Adopt Virtual Wardrobes" Sustainability 14, no. 3: 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031209

APA StyleBang, H., & Su, J. (2022). Who Uses Virtual Wardrobes? Investigating the Role of Consumer Traits in the Intention to Adopt Virtual Wardrobes. Sustainability, 14(3), 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031209