Abstract

Given the extreme importance of improving the accountability of private social solidarity institutions (IPSS), both for reasons of legal compliance and for reasons of improving legitimacy and notoriety among their stakeholders, in order to be accountable to them and in order to maintain their sustainability, this article aims to present a framework designed under a more comprehensive research project for the assessment of IPSS accountability, as well as the preliminary results of a pilot test of Portuguese IPSS. The framework was developed from a combination of methodologies that included a literature review, field work and a focus group, resulting in six dimensions with 76 indicators. For the pilot test, the data were collected by questionnaire for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020. The results of the pilot test, despite the limited number of entities, allowed the identification of some trends and indicators where entities show lower results and where they will have to focus to improve their accountability. Some possible effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were also identified. Therefore, we believe that the framework designed answers the research question: how can we promote accountability (social, financial and economic) in the social economy sector, in particular in the case of IPSS?

1. Introduction

The great demands of stakeholders and the high importance of private social solidarity institutions (IPSS) (acronym in Portuguese, standing for Instituições Particulares de Solidariedade Social) in the Portuguese socio-economic panorama make the transparency and increased accountability (social, financial and economic) of these institutions imperative [1]. In the same sense, Tomé, Bandeira, Azevedo and Costa [2] reinforced that it is necessary to promote the evaluation of results and their disclosure to help to increase their accountability. Decree-Law no.172-A/2014 [3] established a financial supervision model, applicable to IPSS, based on demanding imperative rules, with the view to increasing the accountability of the management of these entities, placing strong pressure for greater accountability (social and corporate responsibility of IPSS’ managers) for their members, funders, users and citizens in general.

There is also a growing need to disseminate good practices and the social impact these institutions have on the community. In Portugal in 2018, more than 90% of social economy entities did not measure their social impact [4].

Despite the various frameworks that has being developed [5,6,7,8,9,10], we still do not have a framework with widespread acceptance. Although the bodies with responsibilities in the sector, such as António Sérgio Cooperative for the Social Economy in Portugal, are carrying out an assessment of the sector’s contribution, they are still very attached to quantitative indicators. However, whether the mission, vision and values of these entities play a significant part of their contributions is difficult to measure.

In that context, the project named “TheoFrameAccountability” (Theoretical framework for promotion of accountability in the social economy sector: the IPSS case) (TFA) aims to answer the following research question: how can we promote accountability (social, financial and economic) in the social economy sector, in particular in the case of IPSS? One of its objectives is to conceptualize a framework that allows stakeholders to evaluate the performance of IPSS, and to allow IPSS to make a self-evaluation of their performance and accountability, meeting the growing need for dissemination of good practices and the social impact they have on the community in which they operate.

To this end, a framework of indicators was developed that provides stakeholders with an assessment of the accountability of IPSS in complying with the principles inherent to the guarantee of the sustainability of these organizations [1].

Considering several authors [5,6,7,8,9,10], it was possible to conclude that the assessment of accountability involves, in addition to economic and financial dimensions, further dimensions that meet the social and environmental aspects, each one presenting several sub-dimensions.

In this study, we propose a framework with the conceived indicators, which resulted from the combination of a literature review with fieldwork and validated through the focus group methodology. This study also aims to identify the main trends of the framework dimensions and sub-dimensions from a pilot test. This test was carried out with seven IPSS which completed the questionnaires made available through the specific platform created by the TFA project and for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020.

In this way, this study contributes, on the one hand, to knowledge by discussing and developing a framework that allows for assessing the accountability of social economy entities, considering various dimensions. On the other hand, it provides entities with a tool that allows them to assess and disclose their accountability. There is also the interest that this evaluation represents for the different stakeholders, namely potential funders, who thus have a better understanding of how their contributions are being used.

This paper is organized as follows: after this first introductory section, the literature review is presented in the second section; the third section presents the research methodology, the framework design is shown in the fourth section, the results of the pilot test are presented and discussed in the fifth section, and the sixth section presents the final considerations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Accountability in Social Economy

Several studies reveal that stakeholders are increasingly demanding higher levels of information, which is also valid for all other sectors of the economy, a fact that cannot be underestimated by non-profit organizations, namely IPSS, and as such, the accountability practices pursued must be adapted to those entities [11,12,13].

In fact, IPSS, which are the focus of this study, should verify whether the accountability practice adopted meets the requirements of their stakeholders, as it may affect the effectiveness and fulfilment of their mission [14]. These authors highlight the primacy given to the economic-financial dimension, to the detriment of other dimensions, which seems contradictory when these organizations have as their main purpose the pursuit of the general interest. The difficulty seems to be, on the one hand, in the lack of an objective definition of quantifiable variables suitable for assessing the impact of the activities developed by the social economy entities, and on the other hand, in the pressure brought to bear by funders and regulatory and supervisory bodies, namely the state.

We cannot fail to highlight the demands placed on IPSS, especially with the entry into force of the revised IPSS statute [3]. This statute establishes a new model for the financial supervision of IPSS, based on denser and demanding mandatory rules in order to increase transparency in the management and accountability of these entities [9].

The concept of accountability, initially linked to accounting, has evolved into a quite different reality. Accountability does not refer only to accounting information, but to the actor’s responsibility for all decisions important/relevant to stakeholders, who may demand explanations and justifications [15]. Additionally, according to this author, the term accountability is increasingly used because it conveys an image of transparency and trust, applicable to any sector, be it the public, private or social economy sector.

According to Bovens [15], accountability is used as a way of positively qualifying a state of affairs or the performance of an actor. It reflects responsiveness and sense of responsibility, and the will to act in a transparent, fair and equitable way, but it also refers to concrete accountability practices.

In the case of IPSS, Connolly and Kelly [16] emphasized the importance that the reporting of these organizations becomes more reliable and transparent, so that with this accounting information of higher quality, one can give visibility to the resources mostly granted by the state, as well as the activities and objectives of the institutions, increasing their notoriety and legitimacy, generating greater confidence among stakeholders. However, the accountability of these institutions goes beyond accounting information, since the decision-making process includes aspects that go beyond this information, simultaneously making the disclosure process more complex, with factors that are more difficult to quantify, such as the social impacts of their activities [16]. The measurement of this kind of impact generated by an IPSS in the community, normally based on non-accounting information, requires the transformation of qualitative information into useful indicators for all stakeholders (Aimers and Walker, 2008a). For Choudhoury and Ahmed [17], accountability was focused, until a few decades ago, on internal controls and auditing, monitoring, evaluation and compliance with rules and regulations. We are now witnessing a paradigm shift: from simple financial accounting to performance auditing and public accountability, i.e., towards all stakeholders.

Becker [18] pointed out the trend of non-profit organizations to adopt new modalities of accountability, which go beyond the minimum legally imposed requirements. In this way, they will have managed to increase their transparency and implement good governance, simultaneously resulting in increased credibility, reputation and capacity to attract funders.

From a conceptual point of view, accountability is often used as a synonym for evaluation, and confused with concepts such as responsiveness, responsibility and effectiveness. In an attempt to analyze a restricted definition of accountability, Bovens [15] emphasizes the existence of a series of dimensions that are associated with it, both from the relational point of view and in terms of the objectives underlying the various areas of governance. Furthermore, accountability is very often associated with good governance or socially responsible behavior, a very relevant factor as far as the IPSS are concerned.

Tomé, Bandeira, Azevedo and Costa [2] drew particular attention to the case of IPSS, to whom more and greater challenges are posed by their stakeholders in general, namely: (i) by the state, given the preferential partnership it maintains with these institutions, in addition to its role as regulator; (ii) by private for-profit companies, whose corporate social responsibility programs bring them into regular contact with these organizations; and (iii) by the need for these non-profit entities to become more efficient and effective, open to internal and external reality, facilitating access and perception of their socially responsible behavior, credibility and transparency at all levels, (economic, social and environmental). Fulfilment of all these requirements implies the effective planning and development of activities, the promotion of the evaluation of results and their disclosure, in compliance with legal obligations or other parameters voluntarily expressed but that may help increase their accountability.

All these interpretations suggest the diversity of dimensions in which accountability is established and which characterize institutions and the way in which they interact with their internal and external environments. According to Bergsteiner and Avery [19], the Integrative Responsibility and Accountability Model considers that two domains exist, the external (accountor) and internal (accountee), which are interconnected—that is, the decisions and perceptions of each influence the other, resulting in responsibilities.

Internally and from their genesis, IPSS should pay special attention to their organizational structure, incorporating new accountability practice mechanisms as a means of increasing knowledge and appropriate forms of governance, promoting their sustainable development [20]. Other studies analyzed the impact of organizational characteristics on the accountability practices of non-profit organizations, establishing relationships between the organizational profile and the level of accountability [21,22,23].

Additionally, according to Arshad, Bakar, Thani and Omar [24], the composition of management bodies influences accountability practices, whose instruments and associated activities may become, in turn, a useful contribution to the current governance systems, but with effects not yet fully known [18]. Additionally, of particular interest is a study lead by Atan, Alam and Said [25], in which the authors assessed the organizational integrity of non-profit organizations and concluded that this contributes significantly to the accountability practices adopted by them.

Equally important is the adequacy of the products and services provided to the community. IPSS cover a broad range of services, particularly in the area of social services, not neglecting education, health, sports and culture, among others, meeting the specific needs of their community, a fact that also increases the imperativeness of accountability [26].

With regard to the external environment, of particular importance is the fact that the sustainable development of IPSS is directly linked to the importance of including stakeholders at all levels of decision-making, improving the practice of accountability, from the rendering of accounts to its justification and influence on the level of positive perception [20]. In the opinion of Aimers and Walker [27], the partnerships between social economy organizations and the state could lead to difficulties in their relationships with the community, and as a result they proposed several models for strengthening the integration of these institutions in their communities, through accountability mechanisms, leading to an increase in their accountability.

Awio, Northcott and Lawrence [28] added that networks and cooperative actions within groups contribute to improving accountability, in the same way that voluntarism and reciprocity work to enhance efficiency and accountability, through donations of time, money and material contributions from the community. Participatory monitoring and evaluation by society was the subject of the study by Sangole, Kaaria, Njuki, Lewa and Mapila [29], who concluded that these actions strengthen social capital while affecting the community’s perception of the organization’s performance, impacting on its accountability.

As mentioned by Ebrhaim [30], accountability is a complex and dynamic concept that encompasses different types of responsibilities, namely for their actions, for shaping their organizational mission and values, for opening themselves to public or external scrutiny, and for assessing performance in relation to goals. In order to fulfil these different responsibilities, accountability is necessarily associated with several sustainability dimensions (financial, social, environmental, technological, and strategic).

In order to improve the sustainable development of social economy organizations on the one hand, and to increase stakeholder confidence on the other, the need to combine modernization and accountability was documented by Santos, Ferreira, Marques, Azevedo and Inácio [31]. They also highlighted the importance of designing quality internal control mechanisms, as a guarantee of good accountability practices, alignment and integration of all stakeholders, raising performance and trust levels, thus resulting not only in individual growth but also in community development. The impact in terms of contribution to the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) should also be highlighted, with a visible result in community terms, but this is often difficult to measure and adequately perceive.

As noted by Ebrahim [30], still missing with regard to accountability is an integrated look at how organizations deal with multiple and sometimes competing accountability demands, while there continues to be a strong difficulty to include dimensions whose calculations are difficult to determine because they include mostly qualitative data. In Portugal, for example, according to INE [4], around 46% of the SE entities did not use indicators for monitoring/assessing the performance of their activity and 93% did not use methods for measuring social impact.

2.2. Accountability Frameworks for Social Economy

Given that many social economy organizations are evaluated by civil society, by the state or by their patrons and donors, there is a need for the institution to communicate its social effectiveness, herein understood as the ability to attain goals and implement strategies utilizing resources in a socially responsible way [5]. Thus, according to the triple bottom line (TBL) concept [32,33], some authors developed frameworks with views to providing a tool to evaluate the accountability of non-profit organizations, observing not only the economic outcome of their activities but also their social and environmental results. However, studies conducted in the social economy field add other concerns beyond the three pillars proposed by the TBL, such as institutional legitimacy [5], community and governance [8]. We are thus led to argue that the TBL is insufficient to communicate, enable understanding and raise awareness among the different stakeholders of social economy entities.

Bagnoli and Megali [5], based on the production process, proposed a framework based on three dimensions. The first dimension is economic and financial performance, which aims, through the annual accounts, to assess economic efficiency and financial balance. The second is social effectiveness, which aims to assess the capacity to achieve goals and implement strategies using resources in a socially responsible way. This dimension should include indicators related to inputs (resources that contribute to the activities developed), outputs (activities carried out to achieve the mission and direct and accountable goods/services obtained through the activities carried out), results (benefits or impact for the intended beneficiaries), and impact (consequences of the activity for the community at large). The third dimension is that of institutional legitimacy, which involves verifying that the organization has respected its “rules” (statute, mission, action program) and the legal norms applicable to its legal form.

The idea that at the basis of social entrepreneurship lies the concept of social benefit was defended by Arena, Azzone, and Bengo [7], for whom the ultimate goal for non-profit organizations is the actual “business idea” that needs to be explored, managed and realized. In this sense, and based on an extensive literature review, the authors proposed a framework, called the Performance Model System (PMS), which is structured into four dimensions: (1) financial sustainability (fundamental to ensure service delivery); (2) efficiency (associated with the relationship between material and human resources used and services provided); (3) effectiveness (associated with the characteristics of the output) and the (4) impact (associated with the outcome—a result measure related to the effects of “production” in the long term).

The effectiveness dimension, closely following Bagnoli and Megali [5], was divided into management effectiveness, related to management strategy and the achievement of objectives, and social effectiveness which concerns the relationship between the non-profit organization and its stakeholders, and which measures the organization’s capacity to meet the needs of its target community by means of the production of goods and services. Due to the importance of this dimension in the social economy sector, the authors divided the social effectiveness dimension into four sub-dimensions: equity (the ability to ensure access to products and services for vulnerable people); involvement (the ability to ensure the participation of relevant stakeholders in the decision-making process) and communication and transparency (the ability to inform stakeholders about the organization’s activities).

In the impact dimension, considering the particularities of non-profit organizations, the authors advocated that one must measure the coherence between the social mission and results. In this sense, the coherence should be evaluated via the connection between the resources employed/used/consumed (inputs), the products/services produced (outputs) and the results achieved (outcomes) that must be consistent with the organization’s mission. In this way, they considered three further sub-dimensions: resource value (the resources used to produce goods or services must be consistent with the organization’s mission); product/service value (the product/service must be consistent with the expected social value of the organization); and outcome value (the final impact of the product or service produced must meet the needs for which the organization works).

Based on the framework presented by Sanford [6], Gibbons and Jacob [10] proposed an adaptation that is structured into five dimensions: (1) beneficiaries; (2) cocreators; (3) land/humanity; (4) community and (5) investors/financiers. The beneficiaries are those for whom programs and services are provided (delivered), i.e., stakeholders; the cocreators are those with whom nonprofit organizations have partnerships and may include volunteers, staff, partner organizations and other stakeholders; land/humanity is the crucial point of the framework, as the relationship with the Earth is applicable to sustainability in any organization, including nonprofit organizations; community refers to how an organization’s actions affect the community, the local perspective and the social context in which they operate; the investors/financiers are funders, contributors, donors, foundations and board members, without whom non-profit organizations could not achieve their mission.

Taking into consideration the particularities of non-profit organizations, Crucke and Decramer [8] proposed a performance measurement instrument sustained in the reliable, valid, and standardized assessment of organizational performance, building a framework based on five dimensions: (1) economic—related to the economic conditions that underpin a strong financial position, which is important for the viability of the organizations. As such, the focus is not on the financial indicators reported in the annual financial reporting, but on the economic indicators that influence these financial indicators; (2) environmental—focused on the efforts that organizations make to protect nature; (3) human—refers to the relationship the organization has with its workforce; (4) community—refers to the manner in which organizations handle their responsibilities in society, including relationships with dominant stakeholders: beneficiaries of the social mission and customers, paying for the products and services delivered; and (5) governance—refers to “systems and processes concerned with ensuring the overall direction, control and accountability of an organization”. The governance performance is a specific performance domain, as good governance practices are expected to have a positive impact on organizational decision making, positively influencing the other performance domains of the organization. When developing this tool, the authors considered that performance is multidimensional and that when assessing performance, the inputs, activities, and outputs should be considered, but not their impact (outcomes). In this decision, they took into consideration Ebrahim and Rangan’s [34] arguments that the conviction to consider outcomes and impacts would be an impediment to developing an adequate tool for social enterprises with diverse activities. For the Portuguese case, considering that social economy entities must behave in a socially responsible manner, Tomé, Meira, and Bandeira [9] proposed a framework organized into the following five categories: (1) human resources; (2) products and services; (3) sustainability; (4) relationship with the community and (5) environmental.

Table 1 presents the summary of accountability frameworks developed specifically for the social economy sector.

Table 1.

Summary of accountability frameworks for social economy.

According to Marques, Santos and Duarte [35], the assessment of accountability is still limited due to the absence of a framework that adequately implements accountability practices in all its dimensions. These authors advocated that the use of new information and communication technologies (ICTs) can contribute to the modernization of the sector, through the creation of institutional websites, where institutions can disclose financial and non-financial information, allowing their stakeholders to assess their mode of operation and performance. The motivation of stakeholders may be improved as the websites become better and more proactive, and both circumstances will contribute to increasing the legitimacy and notoriety of these institutions, with consequent advantages at all levels.

3. Research Methodology

As we saw in the previous point, several authors have been developing frameworks for the social economy sector, but there is still no framework to be used more generally. Furthermore, the studies present the frameworks, but do not present their application to the reality, except for very specific applications or regarding a specific dimension, as can be concluded from our review of the literature and reinforced with the systematic review carried out by Santos et al. [31]. This fact may be associated with the difficulty related to obtaining data, largely due to the low use of ICT in this sector. Thus, the TFA project fills this gap by developing a framework and a platform that allows the collection of data necessary for the framework’s indicators, and their respective dissemination answers the research question “How can we promote accountability (social, financial and economic) in the social economy sector, in particular in the case of IPSS?”.

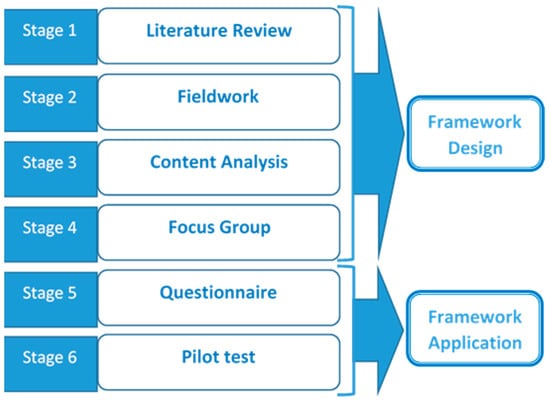

The aim of this paper is to present a framework designed under as well as the preliminary results of a pilot test. Considering this, it was necessary to use a set of methodologies in a 6-stage process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The stages of the methodology process.

The first stage consisted of an extensive literature review which included the themes of the social economy, IPSS, accountability, governance, sustainability and indicators. This literature review enabled the preparation of the fieldwork, which took place between March and July 2019, with the aim of getting to know the IPSS and the environment in which they develop their activity [36], as well as designing the framework.

The second stage consisted of conducting the fieldwork which was planned as suggested by Feldman [37] and Jacob and Furgerson [38]. Since conducting the fieldwork would not be feasible with all the entities in the population, consisting of 5358 IPSS at the time of the study, a representative sample of the study population was defined, adopting a confidence level of 90% and a margin of error of 10%, which resulted in a sample numbering 67 IPSS. The 67 IPSS were randomly selected within each stratum, i.e., legal nature and geographical area. Despite the effort made to contact, visit and conduct the interviews in the IPSS selected for the sample, only 31 interviews were conducted, up to July 2019. Content analysis of the resulting reports served as the basis for the construction of the framework and respective indicators, which was considered as the third stage.

For the validation of the framework and its indicators, in the fourth stage, the focus group methodology was used, which is considered to be the most appropriate methodology for qualitative research studies. Considering the characteristics of this methodology, the focus group took into consideration the type of participants and their particularities, as well as an adequate moderation focused on the objectives to be achieved [39]. The focus group gathered 49 participants selected according to their involvement in the object of analysis (IPSS), and their practical but also theoretical knowledge. After a detailed assessment of the comments obtained from the focus group, the framework was further refined.

In the fifth stage, the questionnaire was developed to collect the data required to compute the indicators. In May 2020, the questionnaire was finalized and submitted to a pre-test, in which ten experts from the academic and professional field participated. This analysis resulted in the final adjustments that allowed the finished questionnaire to be submitted.

Finally, in the sixth stage, a pilot test was carried out to test the framework’s outputs, allowing, on the one hand, one to adjust some inconsistencies in the indicator calculations and, on the other hand, to analyze the results of the indicators to identify trends and draw conclusions. This process aimed to assess whether the framework met its initially defined objectives. The first 7 IPSS that completed the questionnaires for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020 were considered for the pilot test. The number of entities was small, but being related to 3 years for each entity, this allowed us to obtain greater strength for any trends that can be identified.

3.1. Framework Design

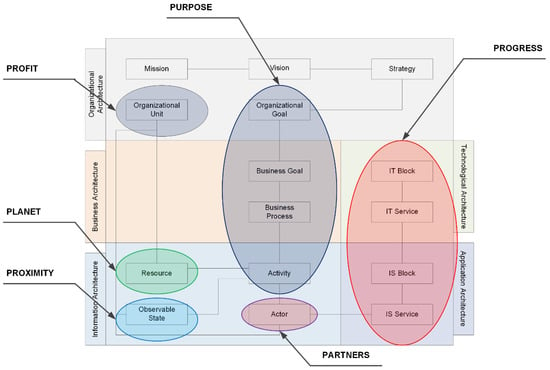

Based on the literature review, we found that the TBL concept [32,33] was the base for several authors who presented diversified proposals for the design of appropriate frameworks to evaluate the accountability of non-profit organizations, considering the social and environmental dimensions in addition to the economic result [5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, aspects such as community and governance were emphasized as being of extreme importance to facilitate the alignment with non-profit organization stakeholders, which in the opinion of Ferreira, Santos and Curi [1] denoted the TBL’s insufficiency to this effect. In their search to find a solution to this deficiency, these authors proceeded in parallel with the analysis of the social economy entities’ production process and arrived at an extension of the dimensions corresponding to the various steps of this process which, completed with views of the organizational architecture, led to a framework organized according to the sextuplet bottom line (SBL) concept with the following dimensions: purpose; partners (extended people concept); profit; proximity; planet and progress (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Combination of SBL dimensions with production process and enterprise architecture. Source: Adapted from Sousa et al. [40].

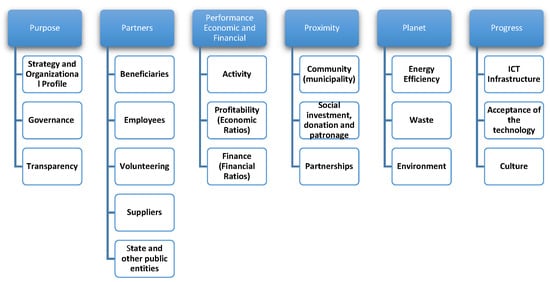

Based on what was described above in terms of the dimensions proposed for the IPSS framework, the TFA project proceeded with its subdivision into relevant areas within each dimension, having focused on the literature [5,6,7,8,9,10] and on the results obtained in the previous fieldwork, where information was collected regarding the daily reality and the specific needs of these institutions. This construction resulted in the following framework structure (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dimensions and sub-dimensions of the framework.

For each dimension/sub-dimension, the indicators considered capable of expressing the relevant information were defined, improving the accountability of the IPSS, whose construction was based on the literature review and on the current practices of these institutions, collected during the fieldwork.

These indicators aim to measure important aspects such as: how the entity defines its mission and strategic objectives, its governance model and transparency; how entities deal with their responsibilities in society, including relationships with stakeholders (beneficiaries, employees, suppliers, State, volunteers, etc.); economic efficiency and the effort to achieve economic balance; how entities relate to the community in which they are inserted (namely through partnerships, employees, suppliers, state, volunteers, etc.); the way entities relate to the community into which they are inserted (namely through the creation of partnerships, social investments and patronage); energy efficiency and relationship with the environment; and the way in which the entity adapts to technological evolution, through the adoption and acceptance of emerging technologies both in the support of its operational activity and in its own promotion to the outside (in Appendix A, you can see a greater detail of the framework, namely, the detailed description of each indicator and the corresponding objective).

In general, 76 indicators were developed, divided by dimension and sub-dimension, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dimensions, sub-dimensions and indicators of the proposed framework.

It should be noted that, in addition to the 76 primary indicators, agglomerated (average) indicators were also proposed which will provide stakeholders with a broader vision of the generality of these institutions, but which may also help to establish a benchmarking process for them.

3.1.1. Presentation and Discussion of Results

To validate and evaluate the analysis framework, a pilot test was carried out which included 7 IPSS, with data referring to the years 2018, 2019 and 2020. The main objective of this test was to calculate the framework’s indicators in its different dimensions and sub-dimensions. This pilot test aimed to identify the main trends, in an analysis by different dimensions, and to analyze the adequacy of the first results in relation to the expectations formulated based on the literature review. The results obtained in the pilot test and its discussion are presented below, in an analysis regarding each of the six dimensions of the framework.

3.1.2. Dimension Purpose

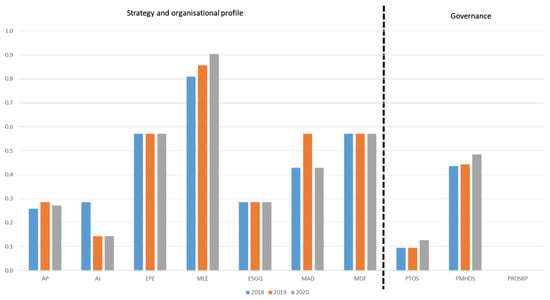

Figure 4 shows the results for the purpose dimension indicators, considering their sub-dimensions (except for the transparency sub-dimension, which, as explained above, is not collected through the questionnaire).

Figure 4.

Results for Purpose dimension indicators.

Legend: The ordinate axis represents the indicators of 2 sub-dimensions of the purpose dimension (strategy and organizational profile; governance). The abscissa axis represents the average of the responses obtained in the pilot test. The average ranges from 0 to 1.

The analysis of Figure 4, with regard to the strategy and organizational profile sub-dimension, shows that the AP indicator (main activities) remains substantially constant during the 3 years under analysis. Through this indicator, it can be seen that the pilot test entities carry out, primarily, approximately 27% of the main activities that, in view of the legislation in force, they can carry out. These results are indicative that the IPSS in the pilot sample seek to specialize and avoid diversification. The AI indicator (instrumental activities) has a low value, decreasing from 2018 to 2019 and maintaining the same value in 2020, indicating that, in that year, only about 15% of the IPSS carry out other activities besides the main one. The joint analysis of these indicators seems to support what was just mentioned and is related to the search for specialization in the activities carried out. However, the fact that a very small percentage of IPSS carry out other activities besides their main one may also indicate a lack of initiative to pursue activities that allow them to be more financially sustainable.

The EPE indicator (existence of a strategic plan) remained constant in the period under review and demonstrates that approximately 57% of the IPSS in the pilot test defined a strategic plan. An identical percentage is obtained for the MDF (function description manual) and MAD (performance assessment models) indicators, although the latter only for the year 2019. The ESGQ indicator (existence of a quality management system) is approximately 28%, meaning that only 28% of IPSS have a quality management system. The MEE (entity’s strategic maturity) indicator is the one with the highest values and has evolved positively over time, standing at 0.9 in 2020. This indicator allows us to conclude that, in that year, 90% of the IPSS had defined their mission, vision and strategic objectives.

In the governance sub-dimension, the PTOS indicator (participation of non-member employees in governing bodies) shows a slight increase in 2020 compared to 2019, but this still indicates that, on average, corporate bodies only include about 10% of non-member employees. As for the PMHOS indicator (parity between women and men in governing bodies), it shows a very slight increase in the period under analysis and, in 2020, its value is very close to 50%, which reflects that in the IPSS in the pilot test, there is parity between men and women. The PROSRP indicator (weight of remuneration of corporate bodies in personnel remuneration) is zero in all periods under analysis, meaning that in the IPSS in the pilot sample, members of the management bodies are not remunerated.

From the results just presented, it is highlighted that it is still necessary for the IPSS to improve their strategy and their organizational profiles, namely through the introduction of management mechanisms such as strategic plans, quality management systems, job description manuals and performance evaluation models, which will allow for greater professionalization of management. The results also show that the IPSS still have to act strongly in the improvement of governance, either through the participation of employees in the management bodies, or through the professionalization of these same management bodies. The evolution of indicators in this dimension does not seem to have been affected by the pandemic caused by COVD-19.

3.2. Partners Dimension

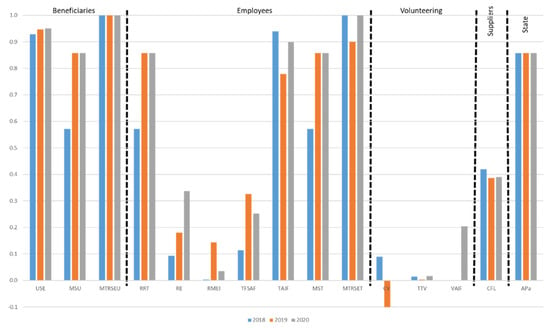

Figure 5 shows the results for the indicators of the partners dimension, considering the sub-dimensions—beneficiaries, employees, volunteering, suppliers and the state.

Figure 5.

Results for the Partners dimension indicators.

Legend: The ordinate axis represents the indicators of the sub-dimensions of the partners dimension (beneficiaries; employees; volunteering; suppliers; state). The abscissa axis represents the average of the responses obtained in the pilot test for the indicators, except for the CV indicator, which represents the variation from the previous year. The average ranges from 0 to 1.

As can be seen in Figure 5, in the beneficiary sub-dimension, the USE indicator (Users Served by the Entity) shows a slight increase from 2018 to 2020. This year, the value of the indicator indicates that the IPSS in the pilot sample serve about 95% of the population, demonstrating that these IPSS serve a number of users that is very close to demand. The MSU indicator (monitoring user satisfaction) also shows growth from 2018 to 2019, remaining the same in 2020. In these last two years, around 85% of the IPSS in the pilot sample assessed user satisfaction. The MTRSEU indicator (monitoring the handling of complaints/suggestions/compliments from users) had a value of 100% in three years, which informs us that the IPSS which assessed user satisfaction dealt with 100% of complaints/suggestions/compliments received from users.

Regarding the employees sub-dimension, the RRT indicator (holding meetings with employees) and the MST indicator (monitoring employees’ satisfaction) show the same values and the same growth trend from 2018 to 2019, both maintaining the value of 2019 in 2020. In these years, the aforementioned indicators show that approximately 85% of the IPSS hold meetings with employees and have a system to monitor their satisfaction. The MTRSET indicator (monitoring the handling of complaints/suggestions/compliments of employees) indicates that in 2018 and 2020, the IPSS in the pilot test dealt with all the complaints/suggestions/compliments of employees. In 2019, the value is a little lower, standing at around 90%. The TAIF indicator (employees who benefit from information and vocational training actions during year N compared to the total number of employees) fluctuates in the period under analysis and stands at approximately 90% in 2020, meaning that this is the percentage of employees which benefited from information and training actions during the year in question.

Additionally, in the employees sub-dimension, the RE indicator (job turnover) shows a growth trend, although this is more accentuated from 2019 to 2020, indicating that in this year, employment turnover was roughly 33%. This sharper increase in job turnover in 2020 may be related to the pandemic situation due to COVID-19; however, given the low turnover, the employment provided by the IPSS in the pilot test can be considered to be lasting. With regard to the RMEI (recourse to inclusive employment measures) indicator, analyzing its values, it appears that the IPSS made very weak use of inclusive employment measures. In 2020, only around 3% of employees were recruited in this way. Finally, the TFSAF indicator (employees with higher education who work in their training area compared to the total number of workers) shows a growth from 2018 to 2019 and a decrease from 2019 to 2020, but this year, about 25% of employees with training superior worked in their area of training.

In the volunteering sub-dimension, all indicators have very low values, and without expression, the CV (volunteer capture) indicator in 2019 is negative, which indicates that the role of volunteers in the entities belonging to the pilot test is still not very significant. This may be due to the requirement of minimum professionals to obtain state subsidies, combined with the need for integration and training of volunteers, which requires time and resources and the need for volunteers to work for the IPSS through a duly established commitment, allowing the IPSS to schedule their activities and make sure they have the required number of volunteers. In the field work, some institutions stated that “It is more complicated to train volunteers than the benefits they bring, because they tend to be just passing through”.

In the suppliers sub-dimension, the CFL indicator (purchases from local suppliers) slightly decreases from 2018 to 2019, and remains constant in 2020. In this year, around 39% of purchases are made from local suppliers.

In the state sub-dimension, the APa indicator (partnership agreements) remains practically constant and close to 85%, indicating the percentage of IPSS in the pilot test that have partnership agreements with public sector institutions.

The analysis of the sub-dimensions of users, employees, volunteers, suppliers and the state shows that the performance level of the indicators by sub-dimension is irregular, with the voluntary sub-dimension showing the worst results. This fact is not surprising given the difficulty that entities face in having volunteers available to regularly carry out the activities. With regard to the sub-dimension of employees, it is important to emphasize the need to adjust the functions performed to the training of employees, making the best use of their skills, as well as devoting more attention to monitoring and addressing the employees’ opinions.

3.3. Dimension Performance

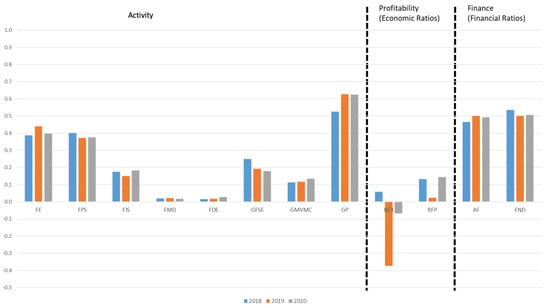

Figure 6 presents the results for the indicators of the performance dimension, considering their activity, profitability and finance sub-dimensions and, in Table 1, the results for the VAB (gross added value) indicators of the profitability sub-dimension, LG (general liquidity), SOL (solvency) and FM (working capital) of the finance sub-dimension.

Figure 6.

Results for the performance dimension indicators.

Legend: The ordinate axis represents the indicators of the sub-dimensions of the performance dimension (activity; profitability; finance). The abscissa axis represents the average of the responses obtained in the pilot test entities for the remaining indicators. All averages vary between 0 and 1, except for the ROI indicator.

The analysis of Figure 6, for the activity sub-dimension, and with regard to the FE financing indicators (state financing compared to total financing), FPS (service provision financing compared to total financing), FIS (social investment financing compared to total funding), FMD (funding of patronage and donations compared to total funding) and FDE (financing of donations in kind compared to total funding), it appears that the fluctuations in temporal terms are very small and that the state funding (which represents between 38 and 44% of the funding) in addition to the financing from the provision of services (amount paid by the user, represents between 38 and 40% of the funding) are the ones that have greater expression, representing, together, approximately 80% of the financing of the IPSS in the pilot sample. Funding from social investors also has some impact (approximately 18% in 2020, the year with the highest value), but that which comes from donors (including in-kind donations) is very small, at approximately 4%. Although our results refer to a very small set of IPSS, when compared with those obtained in a study published by the Confederação Nacional das Instituições de Solidariedade (CNIS) [41], these ratios were situated, respectively, at approximately 39% (state financing), 32% (provision of services), 7% (social investment) and 4% (donations, including in kind), which reveals that, with the exception of funding through patronage, there was some growth in funding through the different channels.

Still in terms of the activity sub-dimension, but now in an analysis of the cost structure, it appears that personnel costs are clearly those that have a greater weight in operating costs (GP indicator), representing about 62% of operating costs in the years 2019 and 2020. This is followed by expenses relating to external supplies and services, which represent approximately 18% of operating expenses (GFSE indicator) in the same years and, finally, expenses relating to goods sold and materials consumed, which represent, in the same period, around 12% of the operating expenses (indicator GMVMC). In the CNIS study [41], personnel expenses represented 58% of the total expenses, with expenses regarding external supplies and services representing approximately 20% of the total expenses and expenses relating to goods sold and materials consumed representing approximately 10% of the total expenses. The comparison with our study cannot be directly analyzed, as our study analyzes the structure of expenses in relation to operating expenses and the CNIS study [41] uses total expenses. However, it is clear that the distribution follows roughly the same proportion. The Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) study [4] carried out for the entire sector of the social economy in Portugal found lower indicators, but even so it confirmed that the main sources of funding come from the state and the amount paid by users.

The analysis carried out indicates that the IPSS should invest more in attracting funders, namely in terms of social investment and donors, and the path of transparency and accountability should be an option. It also demonstrates that the expenditure structure, assuming the character of IPSS service providers, is adequate, since they are heavily dependent on labor.

Regarding the profitability sub-dimension, it appears that the ROI (return on investment (social investment, State, patronage and donations)) is strongly negative in 2019, slightly improving in 2020, but remaining negative, while the return on equity (RFP indicator), although very low, is positive. The year with the worst performance is 2019. In the CNIS study [41], the return on equity was approximately 1%, which is lower than what we obtained. With regard to the VAB (gross added value) (see Table 1), its value grows in the period under analysis. In global terms, although the ROI is very low and even negative in 2019 and 2020, the VAL makes an interesting contribution from the IPSS to the community in which they operate and to the economy in general.

In the finance sub-dimension, it can be seen that the indicator AF (financial autonomy) rises slightly during the period under analysis and stands at approximately 49% in 2020. The END (indebtedness) indicator displays the opposite behavior and, in 2020, stands at approximately 50%. To complete the analysis, and observing Table 3, it appears that both the LG indicator (general liquidity) and the SOL indicator (solvency) have very high values and do not undergo significant variation over the period under analysis. The FM (working capital) indicator has values that, given the general liquidity, can be considered excessive. Considering these results, it is understood that the financial management of entities needs some attention, indicating that the IPSS in the pilot sample could, with more adequate financial management, take advantage of excess short-term funding, improving their financial function.

Table 3.

Results for the VAB, LG, SOL and FM indicators.

When compared to the CNIS study [41] (2018), we found that financial autonomy (approximately 72%), solvency (approximately 2.78) and general liquidity (approximately 5.38) are greater than those obtained in this pilot test.

3.4. Dimension Proximity

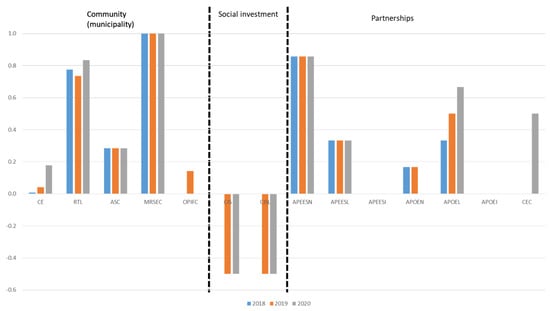

Figure 7 shows the results for the indicators of the proximity dimension in its community, social investment and partnerships sub-dimensions. Table 4 presents the results for the indicators of the social investment, donors and patronage sub-dimensions.

Figure 7.

Results for the indicators of the proximity dimension in its community, social investment and partnerships sub-dimensions.

Table 4.

Results for the social investment, donors and patronage sub-dimension indicators.

Legend: The ordinate axis represents the indicators of the sub-dimensions of the proximity dimension (community; social investment; partnerships). The abscissa axis represents the variation from the previous year for the indicators of the sub-dimension social investment and the average of the responses obtained in the pilot test entities for the remaining indicators. The average ranges from 0 to 1.

As can be seen in Figure 7, in the community sub-dimension, the EC indicator (Job Creation) remained low, showing an increase in 2020, but even so the percentage of job creation in 2020 is below 20%. These values may mean that the IPSS in the sample are in a phase of stability compared to the personnel structure recommended by the state bodies, or that they are unable to increase their staff due to financial constraints. The increase in 2020 may result from the necessary responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The RTL (representation of local employees) indicator presents a small variation in the period under analysis and, in 2020, it is around 83%. This indicator is relevant, showing that the IPSS in the pilot sample essentially attract local employees. The entity’s concern with community satisfaction is still at low levels, since less than 30% of the IPSS in the sample indicate that they assess community satisfaction, as can be seen from the ASC indicator (community satisfaction assessment). Nevertheless, the MRSEC indicator (monitoring the handling of complaints/suggestions/compliments from the community) indicates that the IPSS that assess satisfaction and monitor the complaints/suggestions/compliments of the community handled, throughout the period under review, all complaints/ suggestions/compliments from the community they received. The interaction of the IPSS with the community through the provision of information and training programs to the community, represented by the OPIFC indicator, is also of little significance, since it only presents a value in the year 2019, and only about 15% of the IPSS in the sample indicated that they had provided this offering to the community.

With regard to the partnership sub-dimension, the APEESN (partnership agreements with entities of social economy national counterparts) and APEESL (partnership agreements with entities of social economy local) indicators remain constant during the period under review and are located, respectively, in 86% and 33%. There are no partnership agreements with international social economy entities, represented by the APEESI indicator, and partnerships with other social economy entities, represented by the APOEN indicator, are low in 2018 and 2019, and, in 2020, this value is zero. The APOEL indicator (partnership agreements with local social economy entities) shows an increase in the period under analysis, reaching its maximum value in 2020 at approximately 67%, revealing a strong connection to the community in which the IPSS are located. The CEC (curricular internships) indicator only shows a value in 2020 and is 50%, revealing that the IPSS are managing to attract young people for social economy activity.

With regard to the social investment sub-dimension, the CIS (attracting social investors) and CISL (attracting local social investors) indicators are negative in 2019 and 2020, indicating that the number of social investors decreased compared to 2018. In the same dimension, and as can be seen in Table 4, the indicators CMD (capture of sponsors and/or donors) and CISL (capture of local social investors) rise a lot in 2019, decreasing in 2020 to the levels of 2018. These indicators are variations—the rise in 2019 may be due to COVID-19, which mobilized solidarity and, possibly, the increase in donors also to the IPSS.

From the analysis of this dimension, it can be seen that the contribution of the IPSS to the community is significant, contributing to the dynamization of the community in which they operate, namely in terms of employment and partnerships.

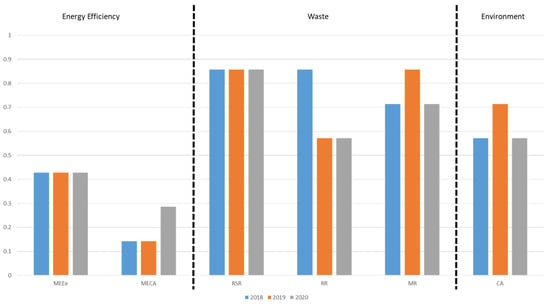

3.5. Dimension Planet

In an analysis of Figure 8, where the results for the indicators of the planet dimension are presented, considering their energy efficiency (MEEe and MECA), waste (RSR, RR and MR) and environment (CA) sub-dimensions, we can assess the planet dimension. It appears that the waste and environment indicators show the strong concern of the IPSS with regard to environmental aspects. In a more detailed analysis, it can be observed that the RSR (selective waste collection), RR (waste reuse) and MR (waste mitigation) indicators, although fluctuating during the period under analysis, present higher values, in most cases (85%), which shows that the entities in the pilot sample use measures to treat or reuse waste. The CA (environmental awareness) indicator also presents values above 50%, in line with what has just been exposed.

Figure 8.

Results for the planet dimension indicators.

Legend: The ordinate axis represents the indicators of the sub-dimensions of the planet dimension (energy efficiency; waste; environment). The abscissa axis represents the average of the responses obtained in the pilot test entities for the remaining indicators. The average ranges from 0 to 1.

The greatest weakness found in this dimension is the energy efficiency sub-dimension, in which the indicators are still low, meaning, in the case of the MEEE (energy efficiency measures) indicator, that only approximately 43% of the IPSS in the pilot sample carried out the implementation of energy efficiency measures. In the case of the MECA (water consumption efficiency measures) indicator, the percentage of IPSS that implemented water consumption efficiency measures is lower, although it rose significantly in 2020, standing at approximately 29%.

From a time perspective, it should be noted that most indicators stagnated between 2019 and 2020, and two indicators (MR and CA) showed a slight decrease in that period. These results are in line with the study by Liu, Bunditsakulchai and Zhuo [42], which showed a substantial change in the pattern of waste generated during the pandemic. Thus, in the case of the entities analyzed, this drop can be justified by the occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which relegated environmental aspects to the background in light of health concerns.

In global terms, it is understood that, from the analysis of the results for this dimension, the IPSS are aware of the need to preserve the environment. However, there is still room for improvement, especially in the energy efficiency sub-dimension, which needs more attention. Occasionally, the fact that less than 50% of the entities in the pilot sample do not have efficiency measures is related to issues of a financial nature.

3.6. Dimension Progress

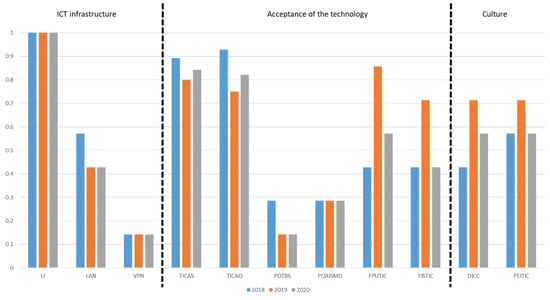

Figure 9 shows the results of the indicators of the progress dimension over the study period, considering the sub-dimensions ICT infrastructure, acceptance of the technology and culture.

Figure 9.

Results for the Progress dimension indicators.

From its analysis and with regard to the ICT infrastructure sub-dimension, a great disparity in behaviors can be verified regarding the adoption of new technologies, with insignificant values being found for the VPN (virtual private network) indicator, which indicates that only about 14% of the IPSS in the pilot test give access via a virtual private network. The percentage of IPSS that own local area network (LAN), although it decreased in 2019 and maintained the same level in 2020, is, for those years, 43%. As for the LI (connection to the internet) indicator, it appears that all IPSS had this connection in the three years studied.

Legend: The ordinate axis represents the indicators of the sub-dimensions of the progress dimension (ICT infrastructure; acceptance of the technology; culture). The abscissa axis represents the average of the responses obtained in the pilot test entities for the remaining indicators. The average ranges from 0 to 1.

When the results of the acceptance of the technology sub-dimension are observed, it is verified through the indicators TICAS (ICT in support activities) and TICAO (ICT in operational activities) that the IPSS in the pilot test already use ICT in the development of their activities, although, from a time point of view, these indicators have decreased slightly compared to 2018. In line with these results are also the results for the FPUTIC (facilitator in the promotion of the use of ICT) and FISTIC (facilitator of interaction with stakeholders through ICT) indicators, in which the IPSS are assumed as facilitators of ICT, and these indicators had the highest value in 2019, at 86 and 71%, respectively. The decrease in this indicator could mean that there was not the expected adhesion by the stakeholders, or even that the IPSS were unable to maintain the same position. In this sub-dimension, the indicators POTBS (online platform for trading goods and/or services) and POAISMD (online platform for attracting social investors) reveal that the IPSS in the pilot test still use these platforms very little. Regarding the presence of these entities on the Internet, according to INE [4], in 2018, 49.7% of the entities in the social economy sector did not have a website or electronic page.

Finally, in the culture sub-dimension, the indicators DICC (dissemination of the cultural identity of the community) and PPEITIC (promotion of intergenerational experiences through ICT) reveal an interesting level of involvement and show that the IPSS in the pilot sample promote the dissemination of experiences through of ICTs, with 2019 being the year in which the highest percentage of IPSS do so (about 71%). From our point of view, the fact that there is a decline in 2020 may be related to the pandemic, which may be due to the lack of conditions required to carry out activities in this forum, given the great demands placed on this type of entity.

In summary, there are no major disparities in the indicators by sub-dimension, but the most accepted sub-dimension is culture, which uses technology to promote the organization’s cultural identity in the community. From a time perspective, the general trend is for improvement until 2019, but there is a significant setback in the year 2020, with most indicators regressing or stagnating, which suggests that despite this dimension being a major concern of the IPSS, they were unable to maintain the effort made in 2019. Given the pandemic context, an increase in the use of new technologies would be expected. The fact that this did not happen may reflect the specificity of the sector under analysis, which privileges other dimensions.

4. Final Considerations

Based on the literature review carried out, we may verify a diversity of approaches to accountability, which impact the various dimensions of the activity of organizations in general and of the IPSS in particular. In this sense, and based on the literature review, a framework was proposed that seeks to contemplate these different dimensions of accountability and which ranges from the concern with the correct definition of the main object of an IPSS (Mission, Vision, Values), evident through the entity’s strategy and organizational profile, to its capacity to incorporate new technologies in favor of adapting to the demands arising from the digital era.

It should be noted that in the accountability assessment process, the relationship that the IPSS maintains with stakeholders, both internally and externally, is extremely relevant, fostering strong and close relationships for the benefit of the community and the sustainable development of the entity itself. Additionally, worthy of reference is the disclosure of its operation and performance, with reports of a social, economic and financial and even environmental nature. The IPSS practice in all these dimensions should be assessed and disclosed, as they are intrinsic factors of the institution and relevant to the improvement of its accountability.

With a view to creating a tool to promote accountability among entities in the social economy sector, we presented a framework with six dimensions: purpose, partners, performance, proximity, planet and progress. Each dimension was subdivided into sub-dimensions and for each one a set of indicators was created, totaling 76 indicators.

In order to assess the framework’s ability to provide information that allows the IPSS to assess their accountability individually and compared with the other IPSS, a pilot test was carried out with seven IPSS and data for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020. From the analysis of the results, it was possible to perform a diagnosis of these IPSS in the various dimensions and sub-dimensions of the framework, with the exception of the transparency sub-dimension. It was also possible to identify trends in the indicators that allow us to perceive the weaknesses and where greater intervention and effort are needed.

In terms of the purpose dimension, the need for the IPSS to improve the strategy and organizational profile was identified, through the introduction of management mechanisms that allow for greater professionalization of management, as well as the need to improve governance or through the participation of workers in the management bodies or through the professionalization of these same management bodies.

With regard to the partners dimension, the low values of the indicators of the voluntary sub-dimension are highlighted, demonstrating the low attractiveness of these entities for attracting volunteers. It was also possible to identify the need to adjust the functions performed by workers to their respective training, as well as devoting more attention to monitoring and treating the workers’ opinions.

With regard to the performance dimension, the low representation of funding via donors and social investors stands out, alerting us to the need for these entities to invest in attracting this type of funding. It was also possible to identify an excess of short-term financing that requires improvement in the financial function of these entities.

Regarding the proximity dimension, it was possible to identify a significant contribution of the IPSS to the community in which they operate, namely through employment and partnerships.

In terms of the planet dimension, it was possible to identify the concern of the entities involved in the pilot test with respect to the preservation of the environment, but that still does not take place in terms of energy efficiency measures, possibly due to the financial restrictions to which they are subject.

Finally, with regard to the progress dimension, it was possible, in general terms, to identify an improvement from 2018 to 2019, but which stagnated or regressed in 2020. Therefore, in this field, there is a significant way to go.

Considering that the years under analysis include the beginning of the pandemic, some of the variations identified can be explained by this condition. In this context, variations were identified in the partners dimension in terms of worker turnover, which could represent a possible negative effect of COVID-19. This result crosses with the job creation indicator, in the proximity dimension, which may have increased in 2020 due to the necessary responses to the pandemic. It is also possible that the setback of indicators related to the progress dimension is linked to the COVID-19 effect, which forced these entities to focus on other aspects that became more urgent during the pandemic period.

On the other hand, the performance dimension does not seem to have suffered significant effects from COVID-19, possibly because support was granted by the State that allowed, in this period, to alleviate the difficulties felt in the context of a pandemic. Additionally, in the evolution of the purpose and planet dimension indicators, it does not seem to have been affected by the pandemic caused by COVID-19.

The framework designed can enable, beyond the diagnosis based on the results obtained from the indicators, the modernization of the social economy sector. This is because, after the diagnosis phase, it is possible for each institution to introduce the necessary improvements to make accountability feasible, which is imperatively required, with the ultimate goal of fulfilling its mission and individual and collective sustainability.

From the pilot test carried out to test the framework’s output, it was possible to perform a diagnosis of the different dimensions, identifying trends even in non-financial aspects, such as low attractiveness to volunteers or strong connection to the local community. Thus, the conclusions that could be drawn even from this small sample allow us to argue that the framework designed answers the research question: how can we promote accountability (social, financial and economic) in the social economy sector, in particular in the case of IPSS? However, as this is an exploratory article, it incorporates the limitation that this is a pilot test with only seven entities (even though 3 years of data were collected and processed in each of the pilot test entities). In this sense, future work proposes the collection of data from a larger number of entities to calculate the indicators with the objective of assessing whether the framework fulfils its objective—the assessment of the accountability of entities in the social economy sector, particularly IPSS. Additionally, it will be interesting to question the entities to know if individually the framework fulfils their needs to evaluate their accountability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; Methodology, A.F. and H.I.; Formal analysis, A.F., H.I. and C.G.; investigation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation A.F., H.I. and B.T.; writing—review and editing A.F. and H.I.; supervision, A.F.; project administration A.F. and R.P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), through Operational Competitiveness and Internationalisation Program (COMPETE 2020—POCI), and the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) financed this research, with reference number POCI-01-0145-FEDER-030074.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Purpose.

Table A1.

Purpose.

| Sub-Dimension | Indicator | Objective | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Strategy and organizational profile | AP | Strategic maturity of the entity | Identify the percentage of activities carried out as main activities in relation to the possible main activities |

| AI | Instrumental activities | Identify the exercise of another activity in addition to the main activity | |

| EPE | Existence of a strategic plan | Assess the existence of a strategic plan | |

| MEE | Strategic maturity of the entity | Assessing strategic maturity | |

| SGQ | Quality management system | Gauging the concern with the quality of the services provided | |

| MAD | Performance evaluation models | Assess the existence of organizational global performance evaluation models | |

| MDF | Job description manual | Evaluate the existence of a job description manual | |

| 1.2 Governance | PTOS | Employees’ participation in governing bodies | To assess the democratic nature and/or heterogeneity of the entity’s governing bodies |

| PMHOS | Parity between men and women in governing bodies | Gauging the concern with the balance between leadership profiles (M/W) | |

| PROSRP | Weight of governing bodies’ remuneration in staff remuneration | Assessing the balance of compensation of the responsibilities assumed | |

| 1.3 Transparency | TE | Transparency | Assess the transparency of the entity |

Table A2.

Partners.

Table A2.

Partners.

| Sub-Dimension | Indicator | Objective | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 Beneficiaries | USE | Users served by the entity in relation to the demand for the social response | Assess whether the entity is able to respond to the needs of the population |

| MSU | Monitoring users’ satisfaction | Evaluate the level of user satisfaction | |

| MTRSEU | Monitoring the handling of complaints/suggestions/compliments from users | Assess the entity’s willingness to deal with complaints and/or suggestions from users | |

| 2.2 Employees | RRT | Carrying out meetings with the employees | Assess whether the entity promotes the participation and integration of employees |

| RE | Job turnover | Assessing whether the entity provides lasting employment | |

| RMEI | Use of inclusive employment measures | Assess whether the entity is concerned with social inclusion | |

| TFSAF | Employees with higher education who work in their field of expertise in relation to the total number of employees | Evaluate the adequacy of the training profile to the activities developed | |

| TAIF | Employees who attended information/training sessions | Gauging the entity’s concern with the professional enhancement of its employees through planned information and professional training actions | |

| HAIFT | Average number of hours of employee information/training actions | Gauging the entity’s concern with the professional enhancement of its employees through planned information and professional training actions | |

| MST | Monitoring employees’ satisfaction | Gauging the concern of the entity with the satisfaction of the employees | |

| MTRSET | Monitoring the handling of employees’ complaints/suggestions/compliments | Assess the sensitivity of the entity to deal with employees’ complaints/suggestions | |

| 2.3 Volunteering | CV | Volunteer recruitment | Assess the entity’s capacity to attract new volunteers |

| TTV | Rate of voluntary work | Assess the amount of work that is done by volunteers | |

| HAIFV | Average number of hours of information/training for volunteers | Assess the entity’s concern with valuing volunteers through programmed information and professional training actions | |

| VAIF | Volunteers who attend information/training sessions | Assess the entity’s concern with valuing volunteers through programmed information/training actions | |

| 2.4 Suppliers | CFL | Purchases from local suppliers | Assess the entity’s concern with local economy |

| 2.5 State and other public entities | APa | Partnership agreements | Evaluate the capacity of the entity to relate to other entities, benefiting its activity |

Table A3.

Performance.

Table A3.

Performance.

| Sub-Dimension | Indicator | Objective | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Activity | FE | State Funding towards total funding | Assess the entity’s dependence on state funding |

| FPS | Service Provision Financing as a percentage of total financing | Assess the dependence of the entity on payments from services provided | |

| FIS | Financing of social investment in relation to total financing | Assess the dependence of the entity on social investment | |

| FMD | Patronage and donations as a proportion of total funding | Assess the entity’s dependence on patronage and donations | |

| FDE | Non-monetary donations as a proportion of total funding | Assess the entity’s reliance on non-monetary donations | |

| GFSE | Expenditure on supplies and external services against operating expenditure | Assess the proportion of external supplies and services in total expenditure | |

| GMVMC | Costs of goods sold and consumed over operating expenses | Assess the proportion of costs of goods sold and materials consumed in total costs | |

| GP | Personnel expenses in relation to operating expenses | Evaluate the proportion of personnel expenditure in total expenditure | |

| 3.2 Profitability (Economic Ratios) | ROI | Return on investment (social investment, state, patronage and donations) | Assess the ability of the entity to create value from the investments received |

| RFP | Return on equity funds | Assess the ability to generate value from self-financing | |

| VAB | Gross value added | Assess the entity’s capacity to create value for the different stakeholders | |

| 3.3 Finance (Financial Ratios) | LG | General liquidity | Assess the ability of the entity to meet its short-term financial commitments |

| FM | Working capital | Assess how the entity manages its exploitation cycle | |

| AF | Financial autonomy | Assess of the entity’s assets that are being financed by equity | |

| SOL | Solvability | To assess the entity’s capacity to meet its medium and long-term commitments | |

| END | Indebtedness | Assess the debt structure of the entity | |

Table A4.

Proximity.

Table A4.

Proximity.

| Sub-Dimension | Indicator | Objective | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 Community (municipality) | CE | Job creation | Assess the level of job creation |

| RTL | Representation of local employees | Assessing the proportion of resident employees | |

| ASC | Evaluation of community’s satisfaction | Gauging the entity’s concern for community satisfaction | |

| MRSEC | Monitoring of complaints/suggestions/compliments from the community | Assess the sensitivity of the entity to listen to the community according to the complaints and/or suggestions made by the community | |

| OPIFC | Offering information/training programs to the community | Assess the capacity of the entity to offer information/training programs to the community | |

| 4.2 Social investment, donations and patronage | CIS | Raising funds from social investors | Assess the capacity of the entity to attract new social investors |

| CISL | Local social investors | Assess the entity’s capacity to attract new local social investors | |

| CMD | Attracting sponsors and donors | Assess the entity’s capacity to attract new patrons and donors | |

| CMDL | Raising local sponsors and donors | Assess the entity’s capacity to attract new local patrons and donors | |

| 4.3 Partnerships | APEESN | Partnership agreements with national social economy entities | Assess the networking capacity of the entity with national counterparts |

| APEESL | Partnership agreements with local social economy entities | Assess the networking capacity of the entity with local entities | |

| APEESI | Partnership agreements with international social economy organizations | Assess the networking capacity of the entity with international entities | |

| APOEN | Partnership agreements with other national entities | Assess the networking capacity of the entity with other national entities | |

| APOEL | Partnership agreements with other local entities | Assess the networking capacity of the organization with other local entities | |

| APOEI | Partnership agreements with other international entities | Assess the networking capacity of the entity with other international entities | |

| CEC | Attracting curricular internships | Assess the ability to attract young students into social work practice | |

Table A5.

Planet.

Table A5.

Planet.

| Sub-Dimension | Indicator | Objective | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 Energy Efficiency | MEEn | Energy efficiency measures | Assess the capacity to implement energy efficiency measures |

| MECA | Water consumption efficiency measures | Assess the concern with the implementation of water consumption efficiency measures | |

| 5.2 Waste | RSR | Selective waste collection | Assess the concern with the implementation of measures for selective waste collection |

| RR | Waste reuse | Gauging the concern with the implementation of waste reuse measures | |

| MR | Waste mitigation | Gauging concern about the implementation of waste mitigation measures | |

| 5.3 Environment | CA | Environmental awareness | Gauging the entity’s concern with the implementation of environmental awareness measures |

Table A6.

Progress.

Table A6.

Progress.

| Sub-Dimension | Indicator | Objective | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1 ICT infrastructure (capacity to adapt to new technologies) | LI | Internet connection | Gauging the entity’s concern about the implementation of measures for internet connection |

| LAN | Local area network | Gauging the entity’s concern for the implementation of a local area network | |

| VPN | Virtual private network | Assess the entity’s concern with the implementation of a virtual private network access. | |

| 6.2 Acceptance of the technology | TICAS | ICT in support activities | Assessing the entity’s capacity to use ICTs in support activities |

| TICAO | ICT in operational activities | Assessing the entity’s capacity to use ICTs in operational activities | |