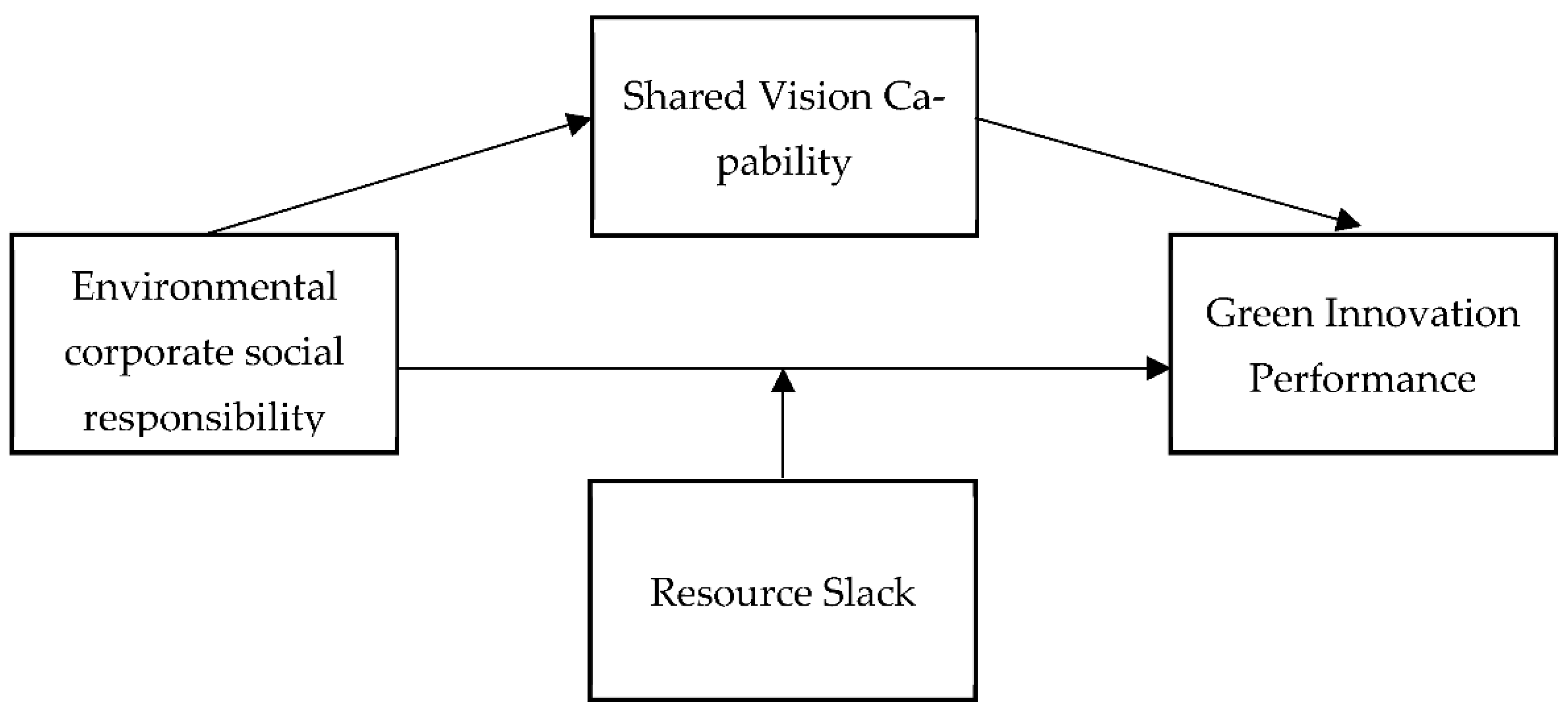

Linking Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility with Green Innovation Performance: The Mediating Role of Shared Vision Capability and the Moderating Role of Resource Slack

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Impact of Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility on Green Innovation Performance

2.2. The Mediating Role of Shared Vision Capability

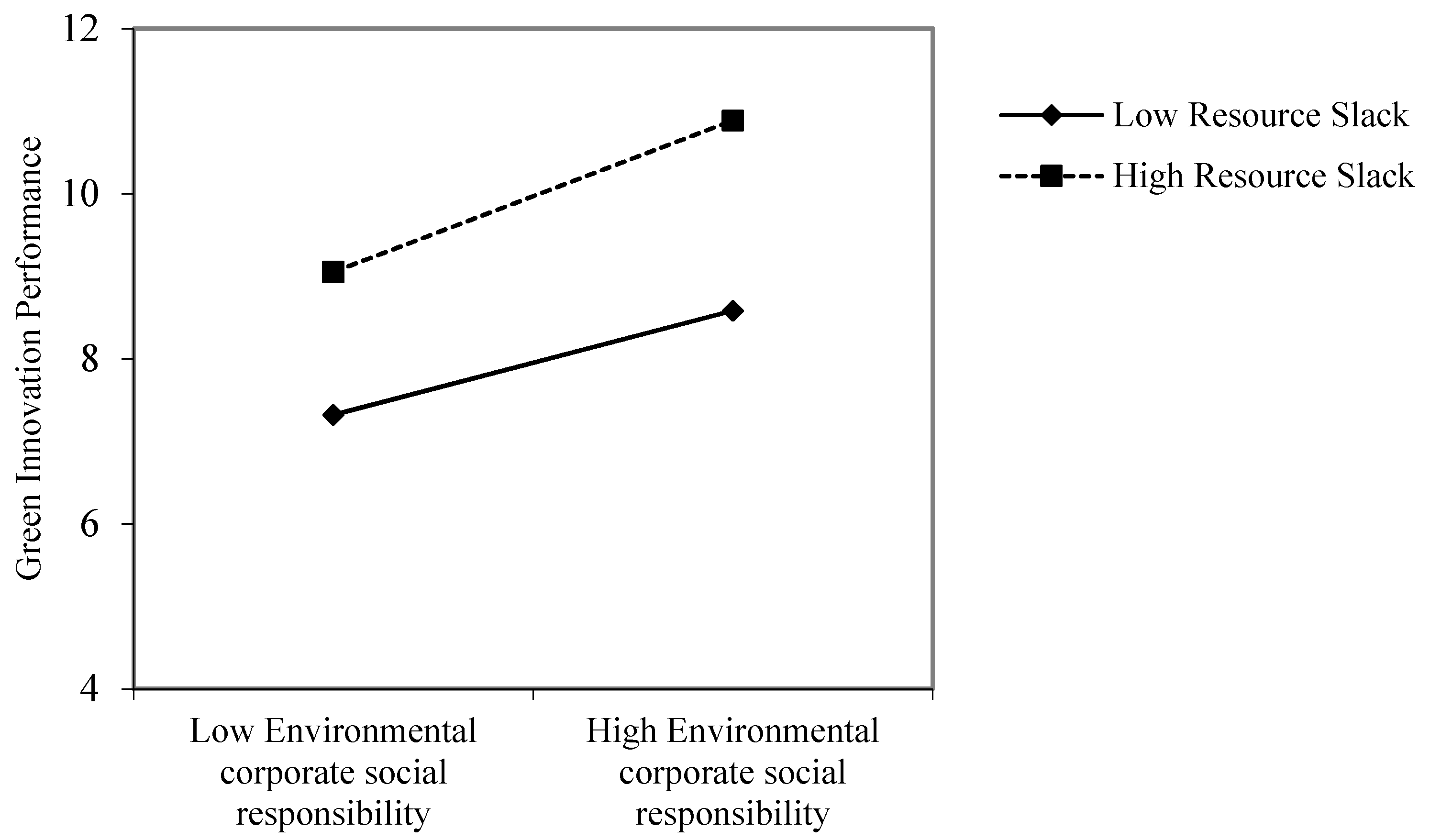

2.3. The Moderating Role of Resource Slack

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility (ECSR)

3.2.2. Shared Vision Capability (SVC)

3.2.3. Resource Slack (RS)

3.2.4. Green Innovation Performance (GIP)

3.2.5. Control Variables (Con)

3.3. Statistical Modeling

3.4. Reliability and Validity

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items Numbers | Measurement Items | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Control Variable 1 | Male Female | Afsar et al. [64]; Liao and Long [31] |

| Age | Control Variable 2 | 30 years old or under 31–40 years old 41–50 years old Over 50 | |

| Education | Control Variable 3 | Senior high school (polytechnic school) or under Junior college Undergraduate Graduate and above | |

| Grade | Control Variable 4 | General staff Junior managers Middle managers Senior managers | |

| Tenure | Control Variable 5 | Fill-in-the-blank question | |

| Firms’ type | Control Variable 6 | Private firms Foreign firms State-owned firms Sino–foreign joint venture | |

| Firms’ size | Control Variable 7 | Fewer than 20 employees 20–50 employees 51–200 employees Over 200 employees | |

| Firms’ Age | Control Variable 8 | 10 years or under Over 10 years | |

| Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility | ECSR1 | Our company participates in activities which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural. | Farooq et al. [62] |

| ECSR2 | Our company makes investments to create a better life for future generations. | ||

| ECSR3 | Our company implements special programs to minimize its negative impact on the natural environment. | ||

| ECSR4 | Our company targets sustainable growth which considers future generations. | ||

| Shared Vision Capability | SVC1 | I fully understand the meaning of our company’s vision and mission and I can fully explain it in detail. | Luo et al. [27] |

| SVC2 | I can understand the meaning of the phrase “make culture” embedded in our vision. | ||

| SVC3 | I fully engaged and in accordance with our company’s vision and mission. | ||

| SVC4 | I can explain our company’s vision and mission and business direction in detail. | ||

| SVC5 | Vision and business direction of our company are adequately set. | ||

| SVC6 | I know what need to do in order to achieve our company’s vision. | ||

| Resource Slack | RS1 | Our company has a pool of uncommitted resources that can quickly be used to fund new strategic initiatives. | Gao and Yang [27] |

| RS2 | Our company can obtain resources at short notice to support new strategic initiatives. | ||

| RS3 | Our company has substantial resources at the discretion of management for funding new strategic initiatives. | ||

| Green Innovation Performance | GIP1 | Our company chooses the materials of the product that produce the least amount of pollution for conducting the product development or design. | Chang et al. [63] |

| GIP2 | Our company chooses the materials of their products that consume the least amount of energy and resources for conducting the product development or design. | ||

| GIP3 | Our company would circumspectly evaluate whether their products are easy to recycle, reuse, and decompose for conducting the product development or design. | ||

| GIP4 | The manufacturing process of our company effectively reduces the emission of hazardous substances or wastes. | ||

| GIP5 | The manufacturing process of our company effectively recycles wastes and emissions that can be treated and reused. | ||

| GIP6 | The manufacturing process of our company effectively reduces the consumption of water, electricity, coal, or oil. |

References

- Qin, Y.; Harrison, J.; Chen, L. A framework for the practice of corporate environmental responsibility in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 426–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D.; Pontrandolfo, P. Green product innovation in manufacturing firms: A sustainability-oriented dynamic capability perspective. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Zou, H.; Xie, X. Governmental inspection and green innovation: Examining the role of environmental capability and institutional development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuryakin, N.; Maryati, T. Green product competitiveness and green product success. Why and how does mediating affect green innovation performance? Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 3061–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesidou, E.; Demirel, P. On the drivers of eco-innovations: Empirical evidence from the UK. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Innovation search of new ventures in a technology cluster: The role of ties with service intermediaries. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, T. Linking green customer and supplier integration with green innovation performance: The role of internal integration. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y. The effects of customer and supplier involvement on competitive advantage: An empirical study in China. Ind. Market. Manag. 2010, 39, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.C.; Wan, S.; Hung. Collaborative green innovation in emerging countries: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W. How to improve green innovation performance: A conditional process analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xi, B.; Wang, G. The impact of corporate environmental responsibility on financial performance-based on Chinese listed companies. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 7840–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, F. Does environmental information disclosure contribute to improve firm financial performance? an examination of the underlying mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 136855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Song, X. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: The roles of government intervention and market competition. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakobyan, N.; Khachatryan, A.; Vardanyan, N.; Chortok, Y.; Starchenko, L. The implementation of corporate social and environmental responsibility practices into competitive strategy of the company. Market. Manag. Innov. 2019, 2, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Rashid, M.A.; Hussain, G.; Ali, H.Y. The effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and firm financial performance: Moderating role of responsible leadership. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.Y.; Lee, H.; Hong, C. Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Focused on corporate contributions. Korean Manag. Rev. 2009, 38, 407–432. [Google Scholar]

- Bacinello, E.; Tontini, G.; Alberton, A. Influence of maturity on corporate social responsibility and sustainable innovation in business performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereskin, F.L.; Campbell, T.C.; Hsu, P.H. Corporate philanthropy, research networks, and collaborative innovation. Financ. Manag. 2016, 45, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J. Nexus between corporate environmental performance and corporate environmental responsibility on innovation performance. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 30, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorobantu, S.; Kaul, A.; Zelner, B. Nonmarket strategy research through the lens of new institutional economics: An integrative review and future directions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 114–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ruan, R.; He, P. The double-edged sword: A work regulatory focus perspective on the relationship between organizational identification and innovative behaviour. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2022, 31, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Park, H. The impact of SME’s organizational capabilities on proactive CSR and corporate performance: The mediating effect of proactive CSR. J. Serv. Res. Stud. 2016, 6, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, M. The influence of corporate social responsibilities on sustainable financial performance: Mediating role of shared vision capabilities and moderating role of entrepreneurship. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, R.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Z. Research on the relationship between environmental corporate social responsibility and green innovative behavior: The moderating effect of moral identity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 52189–52203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Yang, F. Do resource slack and green organizational climate moderate the relationships between institutional pressures and corporate environmental responsibility practices of SMEs in China? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 8, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xie, P.; Zeng, Y.; Li, Y. The effect of corporate social responsibility on the technology innovation of high-growth business organizations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Long, S. CEOs’ regulatory focus, slack resources and firms’ environmental innovation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G. Slack resources and the performance of privately held firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resource and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, L. Customer and supplier collaboration in green product innovation: External and internal capabilities. Bus. Strat. Env. 2017, 27, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The driver of green innovation and green image-green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanath, K.; Pillai, R.R. The influence of green IS practices on competitive advantage: Mediation role of green innovation performance. Inform. Syst. Manag. 2016, 34, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Sarfraz, M.; Khalid, R.; Ozturk, I.; Tariq, J. Does corporate social responsibility and green product innovation boost organizational performance? a moderated mediation model of competitive advantage and green trust. Econ. Res. 2022, 35, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Miao, Z. Corporate social responsibility and collaborative innovation: The role of government support. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Ki, E. Exploring the role of CSR fit and the length of CSR involvement in routine business and corporate crises settings. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, G.; Soberman, D.A. Social responsibility and product innovation. Market. Sci. 2016, 35, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Competing for government procurement contracts: The role of corporate social responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1299–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.C.; Nie, J.; Ran, R.; Gu, Y. Corporate social responsibility, social identity, and innovation performance in China. Pac-Basin Financ. J. 2020, 6, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katila, R. New product search over time: Past ideas in their prime? Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H. The determinants of green radical and incremental innovation performance: Green shared vision, green absorptive capacity, and green organizational ambidexterity. Sustainability 2014, 6, 7787–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Ye, M.; Chau, K.W.; Flanagan, R. The paradoxical nexus between corporate social responsibility and sustainable financial performance: Evidence from the international construction business. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colakoglu, S. Shared vision in MNE subsidiaries: The role of formal, personal, and social control in its development and its impact on subsidiary learning. Thunderbird Int. Bus. 2012, 54, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Rehman, Z.U.; Haider, M.; Ullah, M. Perceived corporate social responsibility and innovative work behavior: The role of employee volunteerism and authenticity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1865–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.J.; Huang, S.Z. A study on the effects of supply chain relationship quality on firm performance under the aspect of shared vision. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2018, 21, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohria, N.; Gulati, R. Is slack good or bad for innovation? Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1245–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Liu, C.G.; Xu, Y.; Hao, Z.R. Effects of strategic flexibility and organizational slack on the relationship between green operational practices adoption and firm performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, J.E.; Olsen, L. Performance outcomes of investing slack resources in corporate social responsibility. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2018, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danneels, E. Organizational antecedents of second-order competences. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Wang, Q.; van Donk, D.P.; van der Vaart, T. When are stakeholder pressures effective? An extension of slack resources theory. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 199, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, F.; Lohrke, F.T.; Fornaciari, C.J.; Turner, R.A. Slack resources and firm performance: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Farooq, O.; Jasimuddin, S.M. Employees response to corporate social responsibility: Exploring the role of employees’ collectivist orientation. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Chen, Y.S. Green organizational identity and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.; Umrani, W. Corporate social responsibility, work meaningfulness, and employee engagement: The joint moderating effects of incremental moral belief and moral identity centrality. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, X.; Qin, H.; Wang, S. Young people’s behaviour intentions towards reducing PM2.5 in China: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2019, 141, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reported in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.I.; Brock, P. Outcomes of perceived discrimination among Hispanic employees: Is diversity management a luxury or a necessity? Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keem, S.; Shalley, C.E.; Kim, E.; Jeong, I. Are creative individuals bad apples? A dual pathway model of unethical behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 103, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate social responsibility on investment recommendations: Analysts’ perceptions and shifting institutional logics. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1053–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Boadu, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ofori, A.S. Corporate social responsibility activities and green innovation performance in organizations: Do managerial environmental concerns and green absorptive capacity matter? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 938682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithani, M.A. Innovation and CSR-do they go well together? Long Range Plan 2017, 50, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szutowski, D.; Ratajczak, P. The relation between CSR and innovation. Model approach. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2016, 12, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshorman, S.; Qaderi, S.; Alhmoud, T.; Meqbel, R. The role of slack resources in explaining the relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and firm market value: A case from an emerging market. J. Sustain. Financ. Inv. 2022, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. The relationship between firms’ corporate social performance and green technology innovation: The moderating role of slack resources1. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 949146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetanto, D.; Jack, S.L. Slack resources, exploratory and exploitative innovation and the performance of small technology-based firms at incubators. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Du, S.; Ding, Y. The relationship between slack resources, resource bricolage, and entrepreneurial opportunity identification-based on resource opportunity perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Category | Quantity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 155 | 44.20% |

| Female | 196 | 55.80% | |

| Age | 30 years old or under | 134 | 38.20% |

| 31–40 years old | 191 | 54.40% | |

| 41–50 years old | 20 | 5.70% | |

| Over 50 | 6 | 1.70% | |

| Education | Senior high school (polytechnic school) or under | 8 | 2.30% |

| Junior college | 52 | 14.80% | |

| Undergraduate | 275 | 78.30% | |

| Graduate and above | 16 | 4.60% | |

| Job grade | General staff | 114 | 32.50% |

| Junior manager | 136 | 38.70% | |

| Middle manager | 92 | 26.20% | |

| Senior manager | 9 | 2.60% | |

| Firm type | Private firm | 204 | 58.10% |

| Foreign firm | 34 | 9.70% | |

| State-owned firm | 96 | 27.40% | |

| Sino–foreign joint venture | 17 | 4.80% | |

| Firm size | Fewer than 20 employees | 11 | 3.10% |

| 20–50 employees | 39 | 11.10% | |

| 51–200 employees | 158 | 45.00% | |

| Over 200 employees | 143 | 40.70% | |

| Firm age | 10 years or under | 118 | 33.60% |

| Over 10 years | 233 | 66.40% |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | Square Root of Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility | ECSR1 | 0.832 | 0.871 | 0.878 | 0.647 | 0.804 |

| ECSR2 | 0.764 | |||||

| ECSR3 | 0.875 | |||||

| ECSR4 | 0.788 | |||||

| Shared Vision Capability | SVC1 | 0.777 | 0.895 | 0.894 | 0.589 | 0.767 |

| SVC2 | 0.799 | |||||

| SVC3 | 0.777 | |||||

| SVC4 | 0.759 | |||||

| SVC5 | 0.815 | |||||

| SVC6 | 0.757 | |||||

| Resource Slack | RS1 | 0.858 | 0.875 | 0.877 | 0.705 | 0.840 |

| RS2 | 0.816 | |||||

| RS3 | 0.850 | |||||

| Green Innovation Performance | GIP1 | 0.836 | 0.934 | 0.935 | 0.707 | 0.841 |

| GIP2 | 0.818 | |||||

| GIP3 | 0.881 | |||||

| GIP4 | 0.854 | |||||

| GIP5 | 0.780 | |||||

| GIP6 | 0.865 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.560 | 0.0497 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 1.710 | 0.651 | –0.071 | |||||||||||

| 3. Education | 2.850 | 0.514 | 0.056 | –0.138 ** | ||||||||||

| 4. Grade | 1.990 | 0.831 | –0.109 * | 0.205 ** | 0.110 * | |||||||||

| 5. Tenure | 6.390 | 5.056 | –0.149 ** | 0.647 ** | –0.059 | 0.211 ** | ||||||||

| 6. Firm type | 1.790 | 1.003 | 0.093 + | 0.046 | 0.139 ** | 0.018 | 0.228 ** | |||||||

| 7. Firm size | 3.230 | 0.769 | –0.193 ** | 0.165 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.165 ** | 0.237 ** | 0.216 ** | ||||||

| 8. Firm age | 1.660 | 0.473 | –0.098 + | 0.211 ** | 0.159 ** | 0.027 | 0.284 ** | 0.145 ** | 0.389 ** | |||||

| 9. ESCR | 4.650 | 0.949 | 0.124 * | –0.009 | 0.030 | 0.060 | –0.039 | –0.070 | –0.032 | –0.081 | ||||

| 10. SVC | 4.060 | 0.751 | 0.066 | 0.034 | 0.012 | 0.063 | 0.027 | –0.083 | 0.041 | –0.016 | 0.361 ** | |||

| 11. GIP | 4.042 | 1.019 | 0.029 | –0.104 + | 0.018 | 0.030 | –0.111 * | –0.069 | 0.047 | –0.081 | 0.343 ** | 0.347 ** | ||

| 12. RS | 4.058 | 1.201 | 0.014 | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.122 * | –0.034 | –0.085 | 0.030 | 0.014 | 0.354 ** | 0.338 ** | 0.394 ** |

| Variables | Shared Vision Capability | Green Innovation Performance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | ||

| Control Variables | Gender | 0.154 + | 0.082 | 0.089 | –0.004 | 0.018 | –0.032 | 0.005 | 0.060 |

| Age | –0.001 | –0.004 | –0.118 | –0.122 | –0.117 | –0.120 | –0.153 | –0.147 | |

| Education | 0.012 | –0.006 | –0.015 | –0.037 | –0.020 | –0.035 | –0.050 | –0.052 | |

| Grade | 0.048 | 0.026 | 0.057 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.019 | –0.010 | 0.007 | |

| Tenure | 0.007 | 0.008 | –0.011 | –0.011 | –0.015 | –0.014 | –0.005 | –0.004 | |

| Firm type | –0.088 * | –0.066 | –0.072 | –0.044 | –0.032 | –0.021 | –0.025 | –0.032 | |

| Firm size | 0.077 | 0.070 | 0.162 * | 0.153 * | 0.127 | 0.129 + | 0.144+ | 0.156 * | |

| Firm age | –0.058 | –0.018 | –0.178 | –0.126 | –0.151 | –0.119 | –0.157 | –0.164 | |

| Independent Variable | ECSR | 0.277 ** | 0.360 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.243 ** | 0.305 ** | |||

| Mediator | SVC | 0.463 ** | 0.347 ** | ||||||

| Moderator | RS | 0.267 ** | 0.254 ** | ||||||

| Interaction Variable | ECSR × RS | 0.126 ** | |||||||

| R2 | 0.025 | 0.143 | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.147 | 0.199 | 0.227 | 0.257 | |

| ΔR² | 0.025 | 0.118 | 0.143 | 0.109 | 0.114 | 0.165 | 0.193 | 0.03 | |

| F | 1.098 | 47.069 ** | 1.499 | 43.210 ** | 45.426 ** | 34.974 ** | 42.408 ** | 13.876 ** | |

| RS | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LCI | Boot UCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean − 1 SD | 0.119 | 0.058 | 0.004 | 0.234 |

| Mean | 0.201 | 0.056 | 0.092 | 0.311 |

| Mean + 1 SD | 0.408 | 0.081 | 0.249 | 0.567 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruan, R.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Z. Linking Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility with Green Innovation Performance: The Mediating Role of Shared Vision Capability and the Moderating Role of Resource Slack. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416943

Ruan R, Chen W, Zhu Z. Linking Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility with Green Innovation Performance: The Mediating Role of Shared Vision Capability and the Moderating Role of Resource Slack. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416943

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuan, Rongbin, Wan Chen, and Zuping Zhu. 2022. "Linking Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility with Green Innovation Performance: The Mediating Role of Shared Vision Capability and the Moderating Role of Resource Slack" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416943

APA StyleRuan, R., Chen, W., & Zhu, Z. (2022). Linking Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility with Green Innovation Performance: The Mediating Role of Shared Vision Capability and the Moderating Role of Resource Slack. Sustainability, 14(24), 16943. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416943