Drina Transboundary Biosphere Reserve—Opportunities and Challenges of Sustainable Conservation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The core area(s) comprises a strictly protected ecosystem that contributes to the conservation of landscapes, ecosystems, species, and genetic variation;

- The buffer zone(s) surrounds or adjoins the core areas, and is used for activities compatible with sound ecological practices that can reinforce scientific research, monitoring, training, and education;

- The transition area is the part of the reserve where the greatest activity is allowed, fostering economic and human development that is socio-culturally and ecologically sustainable [3].

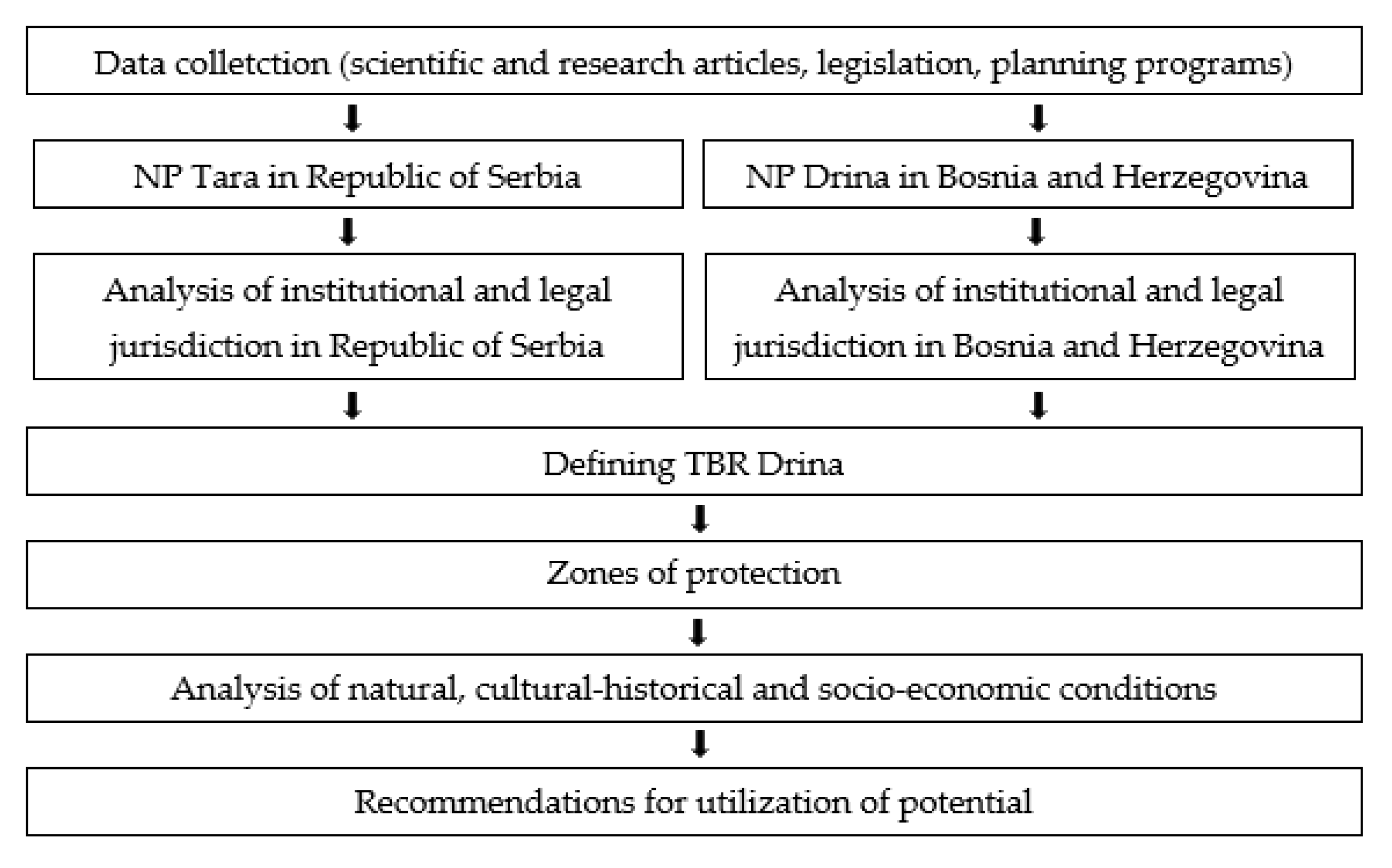

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Geostrategic Framework

| Republic of Serbia | Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-Entity Environmental Body | |||

| Commission to Preserve National Monuments | |||

| Republic of Srpska | Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina | Brčko District | |

| Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management | Ministry of Spatial Planning, Construction, and Ecology | Federal Ministry of Environment and Tourism | Department for Spatial Planning and Property Relations |

| Ministry of Environmental Protection | Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management | Federal Ministry of Spatial Planning | Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management |

| Ministry of Culture and the Media | Ministry of Education and Culture | Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Water Management and Forestry | |

| Ministry of Trade, Tourism, and Telecommunications | Republic Institute for the Protection of Cultural, Historical, and Natural Heritage | Federal Institute for the Protection of Monuments | |

| Ministry of Public Administration and Local Self-Government | Republic Hydrometeorological Institute | Federal Institute of Geology | |

| Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia | Environmental Protection Fund | Federal Hydrometeorological Institute | |

| Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Serbia—Belgrade | |||

| Serbian Environmental Protection Agency | |||

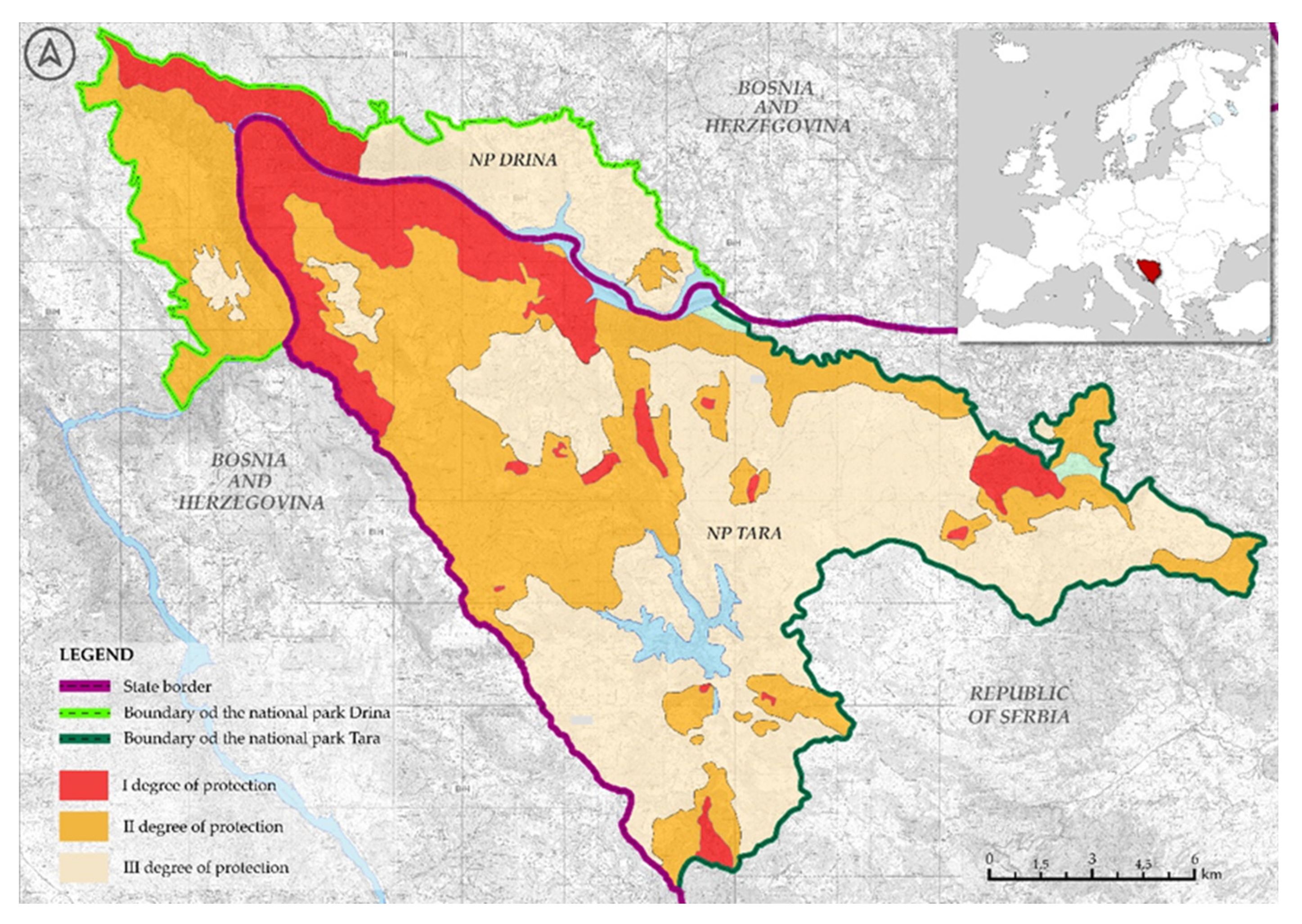

3.2. TBR Drina

- I degree of protection—strict protection is ensured with the possibility of population management, which enables the spontaneous development of natural succession and other ecological processes, the preservation of habitats, living communities, and populations of plants and animals in wild conditions, with insignificant influence and human presence, except for scientific research and controlled education.

- II degree of protection—active protection is provided, which enables limited and controlled use of natural resources and cultural heritage, while activities in the area can be carried out to the extent that enables the improvement of the state and presentation of the protected area, without consequences for its primary value.

- III degree of protection—protection is provided which enables selective and limited use of natural resources and allows controlled interventions and activities in the area, if they are aligned with the management goals of the protected area or following the inherited traditional forms of performing economic activities and housing, including tourist construction.

| Zones of Protection | NP Tara | NP Drina | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area in Ha | % | Area in Ha | % | |

| I degree of protection | 3323.92 | 13.35 | 860.93 | 13.63 |

| II degree of protection | 8514.39 | 34.07 | 2440.35 | 38.64 |

| III degree of protection | 13,153.51 | 52.58 | 3014.04 | 47.73 |

| Total protected area | 24,991.82 | 100.00 | 6315.32 | 100.00 |

3.2.1. Natural Conditions

- The area of the NP Tara represents the selected area for daily butterflies in Serbia and was proclaimed as a Prime Butterfly Area (PBA);

- The broader area of NP Tara has been identified as an Important Bird Area (IBA);

- The broader area of NP Tara has been identified as an Important Plants Area (IPA);

- The Tara area was identified as a significant area within the EMERALD Network;

- and the area NP Tara is recognized as a significant area within the NATURA 2000 ecological network under the Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive [32].

3.2.2. Cultural-Historical Conditions

3.2.3. Socio-Economic Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Urbanization of the area;

- Demographic depopulation of the area and age structure of the population;

- Abandonment of traditional activities;

- Lack of infrastructure;

- Development of inadequate forms of tourism;

- Unlawful use of natural resources.

- Establishing and harmonizing common interests and strategic development;

- Linking and improving common natural resources;

- Development of the protection of the environmental system;

- Preservation and presentation of cultural and historical values;

- Development of infrastructure that will contribute to a simpler flow of goods and people;

- Sustainable development of the area and creation of conditions for the improvement of the quality of life and work of the local population through the promotion of traditional activities (rural tourism, eco-tourism, ethno-tourism);

- Fostering cooperation between citizens, and cultural and public institutions through the realization of joint regional projects;

- Monitoring, scientific observation, and appropriate education;

- Harmonization of all spatial or developmental plans, which should be based on the principles and laws of European regionalism.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves. Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/mab/about (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves. World Network of Biosphere Reserves. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/wnbr (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves. What Are Biosphere Reserves? Available online: https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/about (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Ðorđević, J.S.; Panić, M. Uticaj transgraničnih regiona na razvoj Srbije [The influence transborder regions on the development process in Serbia]. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 2004, 84, 183–196. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živak, N.; Ðorđević, D.; Dabović, T. Prekogranična saradnja—Zajednički izazov Republike Srpske i susjednih zemalja [Cross-border cooperation–a common challenge of Republic of Srpska and neighboring countries]. In Problemi i Izazovi Savremene Geografske Nauke i Nastave; Grčić, M., Ed.; Geografski Fakultet, Univerzitet u Beogradu: Belgrade, Serbia, 2012; pp. 513–520. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, G. Bordering and Ordering in the Twenty-First Century: Understanding Borders; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012; pp. 1–183. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, D. Interrogating Linkages between Borders, Regions, and Border Studies. J. Borderl. Stud. 2015, 30, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hataley, T.; Leuprecht, C. Determinants of Cross-Border Cooperation. J. Borderl. Stud. 2018, 33, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, J.; Pérez-Chinarro, E.; Coral, B.V. Network of Landscapes in the Sustainable Management of Transboundary Biosphere Reserves. Land 2020, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, S. Turizam kao faktor prostorne integracije i socioekonomskog razvoja Donjeg Podrinja [Tourism as a factor of spatial integration and socioeconomic development of Donje Podrinje]. Ph.D. Thesis, Geografski Fakultet, Univerzitet u Beogradu, Belgrade, Serbia, 2020. Available online: http://phaidrabg.bg.ac.rs/o:23194 (accessed on 20 September 2022). (In Serbian).

- Stankov, S.; Perić, M.; Doljak, D.; Vuković, N. The Role of Euroregions as a Factor of Spatial Integration and regional development–the focus on the selected border area. J. Geogr. Inst. Cvijic 2021, 71, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart-Hodge, T.D.; Schoon, M. The challenges and opportunities of transboundary cooperation through the lens of the East Carpathians Biosphere Reserve. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medar-Tanjga, I.; Živak, N.; Zekanović, I.; Popov, T.; Tanjga, M. The Drina Cross-Border Biosphere Reserve as an Instrument for Territorial Integration and Formation of a Unique System for Protecting Natural and Social Heritage. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Energy, Environment, Ecosystems and Sustainable Development (EEESD ’13), Lemesos, Cyprus, 21–23 March 2013; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Josipović, M. Feasibility Study on Establishing Transboundary Cooperation in the Potential Tara-Drina National Park; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; IUCN Programme Office for South-Eastern Europe: Belgrade, Serbia, 2011; pp. 1–32. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/12832 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Law on National Parks; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 39/1993, 44/1993, 53/1993, 67/1993, 48/1994, 101/2005, 36/2009, 84/2015, 95/2018; Government of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Radović, D.I.; Stevanović, V.B.; Marković, D.; Jovanović, S.D.; Džukić, G.; Radović, I. Implementation of GIS technologies in assessment and protection of natural values of Tara National Park. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2005, 57, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, D.; Andrian, G.; Radović, I.; Srdić, Z.; Protić, D. Evolving GIS technologies in nature conservation and the spatial planning strategy of Tara NP (Serbia) as a potential UNESCO MAB reserve. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 2008, 88, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska. Law on NP Drina; Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska No. 63/2017; Government of Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2017. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ishwaran, N. (Ed.) The Biosphere; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasaev, G.; Sadovenko, M.; Isaev, R.O. Biosphere reserve−the Actual Research Subject of the Sustainable Development Process. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2016, 11, 8911–8929. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.G.; Price, F.M. (Eds.) UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. Supporting Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability, and Society, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioras, A.; Pliakas, F.; Diamantis, I. The Legislative Framework and Policy for the Water Resources Management of Transboundary Rivers in Europe: The Case of Nestos/Mesta River, between Greece and Bulgaria. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M.; Worboys, G.; Kothari, A. (Eds.) Managing Protected Areas: A Global Guide; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Těšitel, J.; Kušová, D. The more institutional models, the more challenges–Biosphere reserves in the Czech Republic. In UNESCO Biosphere Reserves–Supporting Biocultural Diversity, Sustainability and Society, 1st ed.; Reed, M.G., Price, M.F., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, A.; Seidlová, A. UNESCO Transboundary Biosphere Reserves as laboratories of cross-border cooperation for sustainable development of border areas. The case of the Polish–Ukrainian borderland. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2022, 57, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrikova, H. Good Practices in Sustainable Transboundary Cooperation—The Krkonoše/Karkonosze Biosphere Reserve. In Crossing Borders for Nature. European Examples of Transboundary Conservation; Vasiljević, M., Pezold, T., Eds.; IUCN Programme Office for South-Eastern Europe: Gland, Switzerland; Belgrade, Serbia, 2011; pp. 35–39. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/2011-025.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Law on Nature Protection; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 36/2009, 88/2010, 14/2016, 95/2018; Government of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Law on Environmental Protection; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 135/2004, 36/2009, 43/2011, 14/2016, 76/2018, 95/2018; Government of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Law on Cultural Property; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 71/1994, 52/2011, 99/2011, 6/2020, 35/2021; Government of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Law on Cultural Heritage; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 129/2021; Government of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Construction, Transport and Infrastructure of the Republic of Serbia. Prostorni Plan Područja Posebne Namene NP Tara [Spatial Plan for the Special Purpose Area of the NP Tara]; Department for Spatial Planning, Urban Development and Housing, Ministry of Construction, Transport and Infrastructure of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- PC National Park Tara. Plan Upravljanja NP Tara za Period 2018–2027 Godine [National Park Tara Management Plan for the Period 2018–2027]; PC National Park Tara: Bajina Bašta, Serbia, 2018. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Telbisz, T.; Ćalić, J.; Kovačević-Majkić, J.; Milanović, R.; Brankov, J.; Micić, J. Karst Geoheritage of Tara National Park (Serbia) and Its Geotouristic Potential. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević-Majkić, J.; Ćalić, J.; Micić, J.; Brankov, J.; Milanović, R.; Telbisz, T. Public knowledge on karst and protected areas: A case study of Tara National Park, Serbia. Hung. Geogr. Bull. 2022, 71, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivić, R.; Josić, D.; Dinić, Z.; Dželetović, Z.; Maksimović, J.; Stanojković Sebić, A. Water quality of the Drina River as a source of irrigation in agriculture. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Scientific Agricultural Symposium „Agrosym 2014“, Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 23–26 October 2014; pp. 795–801. [Google Scholar]

- Radovanović, M. (Ed.) Tara–Lexicons of National Parks of Serbia; Službeni Glasnik, Geographical Institute „Jovan Cvijić“ SASA: Belgrade, Serbia; Public Enterprise „Tara National Park“: Bajina Bašta, Serbia, 2015; pp. 1–364. ISBN 978-86-519-1899-8. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Leščešen, I.; Pantelić, M.; Dolinaj, D.; Stojanović, V.; Milošević, D. Statistical analysis of water quality parameters of the Drina River (West Serbia), 2004–2011. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2015, 24, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecelj, M.; Vagić, N.; Ristić, D.; Šušnjar, S.; Bogdanović, U. Assessment of the natural environment for the purposes of recreational tourism–example on Drina River flow (Serbia). Eur. J. Geogr. 2019, 10, 85–96. Available online: https://gery.gef.bg.ac.rs/handle/123456789/1016 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Brankov, J.; Pešić, A.M.; Joksimović, D.M.; Radovanović, M.M.; Petrović, M.D. Water Quality Estimation and Population’s Attitudes: A Multi-Disciplinary Perspective of Environmental Implications in Tara National Park (Serbia). Sustainability 2021, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomićević, J.; Bjedov, I.; Gudurić, I.; Obratov-Petković, D.; Shannon, M.A. Tara National Park–Resources, Management, and Tourist Perception. In Protected Area Management; Sladonja, B., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankov, J.; Jojić, G.T.; Pešić, A.M.; Petrović, M.D.; Tretiakova, T.N. Residents’ perceptions of tourism impact on the community in national parks in Serbia. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 124–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankov, J.; Micić, J.; Ćalić, J.; Kovačević-Majkić, J.; Milanović, R.; Telbisz, T. Stakeholders’ Attitudes toward Protected Areas: The Case of Tara National Park (Serbia). Land 2022, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, D. Spatial characteristics of the Podrinje region. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 2015, 95, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobričić, M.; Maksić Mulalić, M. Sustainable Spatial Development of the Tara National Park. In Proceedings of the 7th International Scientific Conference–ERAZ 2021, Knowledge-Based Sustainable Development, Online, 27 May 2021; pp. 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkov, B.; Ðorđević, A. Značaj transgraničnog planiranja Podrinja za prostornu integraciju Zapadnog Balkana [Meaning of crossborder planning in western Balkan countries]. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 2004, 84, 113–124. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepić, M. Podrinje–od pogranične regije do potencijalne osovine razvoja [Podrinje–from a frontier region to a potential axis of development]. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 1995, 85, 27–36. Available online: https://digitalna.nb.rs/view/URN:NB:RS:SD_009D9BE9B60FF0ED17AA71C7413495B7-1995-B075#page/13/mode/1up (accessed on 20 September 2022). (In Serbian).

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska. Law on Nature Protection; Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska No. 50/2002, 34/2008, 59/2008, 20/2014; Government of Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2014. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska. Law on Environmental Protection; Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska No. 53/2002, 109/2005, 41/2008, 29/2010, 71/2012, 79/2015, 70/2020; Government of Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2020. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska. Law on National Parks; Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska No. 75/2010; Government of Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2010. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska. Law on Cultural Property; Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska No. 11/1995, 103/2008, 38/2022; Government of Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2022. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Spatial Planning, Construction and Ecology of the Republic of Srpska. Izmjene i Dopune Prostornog Plana Republike Srpske do 2025. Godine [Amendments to the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Srpska until 2025]; Public institution New Urban Institute of the Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2015. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević, D. Nacionalni park „Drina“–smisao i značaj [„Drina“ National Park meaning and significance]. Kult. Nasljeđe 2018, 1, 213–219. Available online: https://doisrpska.nub.rs/index.php/KN (accessed on 20 September 2022). (In Serbian).

- Panić, G.; Nagradić, S. Zaštita Prirodnog Nasljeđa u Republici Srpskoj [Protection of Natural Heritage in the Republic of Srpska]; The Republic Institute for Protection of Cultural, Historical and Natural Heritage of The Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2019; pp. 1–134. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Law on Territorial Organization of the Republic of Serbia; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia No. 129/2007, 18/2016, 47/2018, 9/2020; Government of Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zekanović, I. Etnodemografske Osnove Političko-Geografskog Položaja Republike Srpske [Ethno-Demographic Basis of the Political-Geographical Position of the Republic of Srpska]; Geografsko društvo Republike Srpske: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2011; pp. 1–216. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska. Decision to Establish an Inter-Entity Environmental Protection Body; Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska No. 116/2006; Government of Republic of Srpska: Banja Luka, Republic of Srpska, 2006. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- The Official Gazette of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Decision on the Commission to Preserve National Monuments; Official Gazette of Bosnia and Herzegovina No. 1/2002, 10/2002; Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2002. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Gajić, M.; Kojić, M.; Karadžić, D.; Vasiljević, M.; Stanić, M. Vegetacija Nacionalnog Parka Tara [Vegetation of Tara National Park]; Šumarski Fakultet Beograd, Nacionalni Park Tara: Bajina Bašta, Serbia, 1992; pp. 1–128. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Vasić, V. Pregled faune ptica planinskog kompleksa Tara, Zapadna Srbija [Overview of the bird fauna of the Tara mountain complex, Western Serbia]. Arch. Biol. Sci. 1977, 29, 69–81. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Puzović, S.; Grubač, B. Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In Important Bird Areas in Europe: Priority Sites for conservation. Volume 2: Southern Europe; Heat, M.F., Evans, M.I., Eds.; BirdLife International: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 725–745. [Google Scholar]

- Jakšić, P. Yugoslavia. In Prime Butterfly Areas in Europe; Priority Sites for Conservation; Van Sway, C., Waren, M., Eds.; De Vlinderstichting: Wageningen, The Netherland, 2003; pp. 655–684. [Google Scholar]

- IPCHNHRS (Institute for Protection of Cultural, Historical and Natural Heritage of the Republic of Srpska). Register of Protected Natural Assets. Available online: https://nasljedje.org/registar-zasticenih-prirodnih-dobara/ (accessed on 28 September 2022). (In Serbian).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Convention. Stećci Medieval Tombstone Graveyards. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1504 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Convention. Mehmed Paša Sokolović Bridge in Višegrad. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1260 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Cincotta, R.; Wisniewski, J.; Engelman, R. Human population in the biodiversity hotspots. Nature 2000, 404, 990–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomićević, J.; Shannon, M.A.; Milovanović, M. Socio-Economic Impacts on the Attitudes towards Conservation of Natural Resources: Case Study from Serbia. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järv, H.; Kliimask, J.; Ward, R.; Sepp, K. Socioeconomic Impacts of Protection Status on Residents of National Parks. Eur. Countrys. 2016, 8, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wiering, M.; Verwijmeren, J. Limits and Borders: Stages of Transboundary Water Management. J. Borderl. Stud. 2012, 27, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts, R.; Gordon, J.E. Geoconservation in protected areas. Parks 2014, 20, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertzky, B.; Bertzky, M.; Worboys, G.L.; Hamilton, L.S. Eart’s natural heritage. In Protected Area Governance and Management; Worboys, G.L., Lockwood, M., Kothari, A., Ferary, S., Pulsford, I., Eds.; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2015; pp. 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- Van Oudenhoven, J.P.; Van der Zee, K.I. Successful International Cooperation: The Influence of Cultural Similarity, Strategic Differences, and International Experience. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 51, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; O’Dowd, L.; Wilson, T.M. (Eds.) Culture, Co-operation, and Borders. In Culture and Cooperation in Europe’s Borderlands; Rodopi: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, K. Europe’s Borders: The Narrative Construction of the Boundaries of Europe. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2006, 9, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D. On Borders and Power: A Theoretical Framework. J. Borderl. Stud. 2003, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurđić, S.; Filipović, D. Tretmani zaštićenih prirodnih dobara u sistemu prostornih planova [A treatment of protected natural assets in the system of spatial plans]. Bull. Serb. Geogr. Soc. 2005, 85, 241–248. Available online: https://gery.gef.bg.ac.rs/handle/123456789/127 (accessed on 20 September 2022). (In Serbian).

- Bergs, R. Cross-border Cooperation, Regional Disparities and Integration of Markets in the EU. J. Borderl. Stud. 2012, 27, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnjato, R.; Živak, N.; Medar-Tanjga, I. Institutional framework and development aspects of protected areas in the Republic of Srpska. Herald 2010, 14, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medar-Tanjga, I.; Živak, N.; Ivkov-Džigurski, A.; Rajčević, V.; Mišlicki Tomić, T.; Čolić, V. Drina Transboundary Biosphere Reserve—Opportunities and Challenges of Sustainable Conservation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416733

Medar-Tanjga I, Živak N, Ivkov-Džigurski A, Rajčević V, Mišlicki Tomić T, Čolić V. Drina Transboundary Biosphere Reserve—Opportunities and Challenges of Sustainable Conservation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(24):16733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416733

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedar-Tanjga, Irena, Neda Živak, Anđelija Ivkov-Džigurski, Vesna Rajčević, Tanja Mišlicki Tomić, and Vukosava Čolić. 2022. "Drina Transboundary Biosphere Reserve—Opportunities and Challenges of Sustainable Conservation" Sustainability 14, no. 24: 16733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416733

APA StyleMedar-Tanjga, I., Živak, N., Ivkov-Džigurski, A., Rajčević, V., Mišlicki Tomić, T., & Čolić, V. (2022). Drina Transboundary Biosphere Reserve—Opportunities and Challenges of Sustainable Conservation. Sustainability, 14(24), 16733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416733