Efforts Proposed by IOC to Alleviate Pressure on Olympic Games Hosts and Evidence from Beijing 2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The actual OG governance;

- The preparation and operation of Beijing 2022 and synergies of stakeholders;

- The problems facing the IOC regarding the bidding and hosting of OG;

- Measures taken by the IOC to alleviate the workload of OCOGs;

- The future advice for attracting more Olympic hosts.

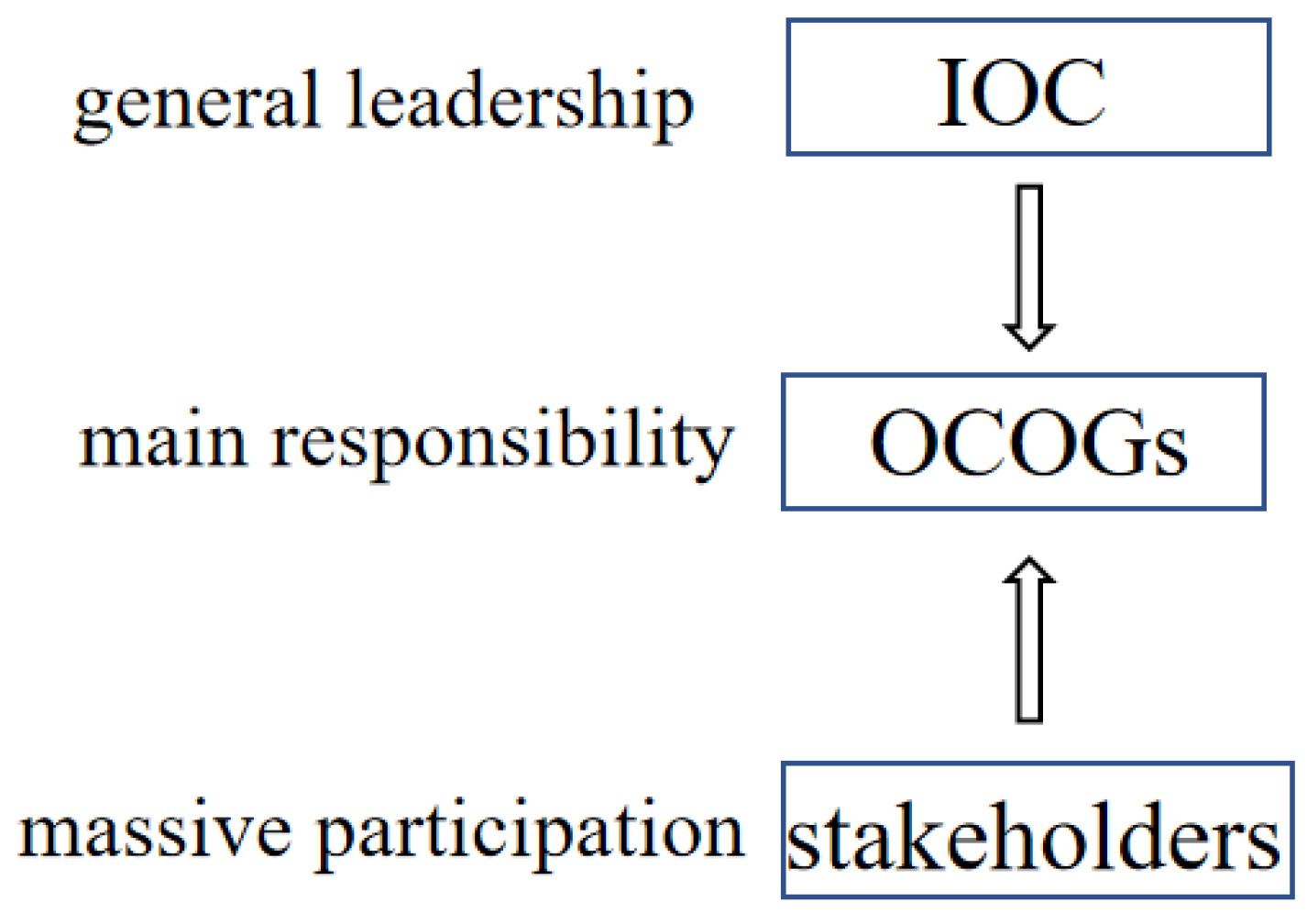

3. Olympic Games Governance Model

3.1. Cooperation between Stakeholders

3.2. Policy Tool Promulgated by IOC

4. Major Initiatives

4.1. IOC: To Reduce Economic Costs and Increase Financial Support

4.2. IOC Subsidiaries: To Outsource Services

4.2.1. Cost Saving

4.2.2. Accumulation of Savoir Faire

4.2.3. Quality of Broadcasting

4.3. Official Partners and Stakeholders: To Be Involved and Share the Workload

4.4. OCOGs: To Transfer Organising Knowledge

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charitas, P. Imperialisms in the Olympics of the Colonization in the Postcolonization: Africa into the International Olympic Committee, 1910–1965. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2015, 32, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R. Women athletes in the Olympic Games. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2019, 14, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.E.C. The Palgrave Handbook of Feminism and Sport, Leisure and Physical Education; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 479–495. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann, A. The Olympics, a History of the Modern Games; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA; Chicago, IL, USA, 2002; pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes dos Santos, G.; Gonçalves, J.; Condessa, B.; Nunes da Silva, F.; Delaplace, M. Olympic Charter Evolution Shaped by Urban Strategies and Stakeholder’s Governance: From Pierre de Coubertin to the Olympic Agenda 2020. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2021, 38, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Pitts, A. A brief historical review of Olympic urbanization. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2006, 23, 1232–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. Operational Requirements for Host City Contracts. Available online: https://library.olympics.com/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/171361/host-city-contract-operational-requirements-international-olympic-committee?_lg=en-GB (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Grix, J.; Kramareva, N. The Sochi Winter Olympics and Russia’s unique soft power strategy. Sport Soc. 2015, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Broom, D.; Wilson, R. Legacy of the Beijing Olympic Games: A non-host city perspective. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinxia, D. The Beijing Games, National Identity and Modernization in China. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2010, 27, 2798–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Modernizing China in the Olympic Spotlight: China’s National Identity and the 2008 Beijing Olympiad. Sociol. Rev. 2006, 54, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassens-Noor, E. Transport Legacy of the Olympic Games, 1992–2012. J. Urban Aff. 2013, 35, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsson, A.; Alm, J. Passing on the torch: Urban governance, mega-event politics and failed olympic bids in Oslo and Stockholm. City Cult. Soc. 2020, 20, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenskyj, H.J. Olympic ideals and the limitations of liberal protest. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2017, 34, 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, J.; Vogelpohl, A. Fragile growth coalitions or powerful contestations? Cancelled Olympic bids in Boston and Hamburg. Environ. Plan. A: Econ. Space 2017, 49, 1887–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassens-Noor, E.; Lauermann, J. Mechanisms of policy failure: Boston’s 2024 Olympic bid. Urban Stud. 2017, 55, 3369–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOIympics, L.A. Available online: https://nolympicsla.com (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Makes Historic Decision in Agreeing to Award 2024 and 2028 Olympic Games at the Same Time. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/ioc-makes-historic-decision-in-agreeing-to-award-2024-and-2028-olympic-games-at-the-same-time (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Leopkey, B.; Parent, M.M. Olympic Games Legacy: From General Benefits to Sustainable Long-Term Legacy. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2012, 29, 924–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheu, A.; Preuß, H.; Könecke, T. The legacy of the Olympic Games: A review. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2021, 6, 212–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopkey, B.; Salisbury, P.; Tinaz, C. Examining Legacies of Unsuccessful Olympic Bids: Evidence from a Cross-Case Analysis. J. Glob. Sport Manag. 2021, 6, 264–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, J. Temporary projects, durable outcomes: Urban development through failed Olympic bids? Urban Stud. 2015, 53, 1885–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. Olympic Games: The New Norm. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/new-norm#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20New%20Norm%E2%80%9D%2C%20an%20ambitious%20set%20of%20118,International%20Olympic%20Committee%20%28IOC%29%20at%20its%20132nd%20Session (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. Basic Universal Principles of Good Governance of the Olympic and Sports Movement. Available online: https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/Who-We-Are/Commissions/Ethics/Good-Governance/EN-Basic-Universal-Principles-of-Good-Governance-2011.pdf#_ga=2.95058908.1537066975.1596529922-1497968687.1556891426 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- The Commission on Global Governance. Our Global Neighbourhood; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chappelet, J.-L. From Olympic administration to Olympic governance. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M.; Rouillard, C.; Naraine, M. Network governance of a multi-level, multi-sectoral sport event: Differences in coordinating ties and actors. Sport Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, K.G.; Kenis, P. Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2007, 18, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’toole, L.J. Treating networks seriously: Practical and research-based agendas in public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 1997, 57, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, MS, USA, 2009; pp. 77–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Networks, Network Governance, and Networked Networks. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2006, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamensky, J.M.; Burlin, T.J. Collaboration: Using Networks and Partnerships, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mandell, M.; Steelman, T. Understanding what can be accomplished through interorganizational innovations The importance of typologies, context and management strategies. Public Manag. Rev. 2003, 5, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, M.P. Collaboration through network structures for community building efforts. Natl. Civ. Rev. 2001, 90, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M. Evolution and Issue Patterns for Major-Sport-Event Organizing Committees and Their Stakeholders. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 135–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Strategic Management (Pitman Series in Business and Public Policy). A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Parent, M.; Deephouse, D. A Case Study of Stakeholder Identification and Prioritization by Managers. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 75, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. Olympic Charter. Available online: https://library.olympics.com/default/olympic-charter.aspx?_lg=en-GB#:~:text=The%20Olympic%20Charter%20is%20the%20codification%20of%20the,conditions%20for%20the%20celebration%20of%20the%20Olympic%20Games (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. Olympic Agenda 2020. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/Documents/Olympic-Agenda-2020/Olympic-Agenda-2020-127th-IOC-Session-Presentation.pdf#_ga=2.132335174.976982587.1624007350-105845724.1620955608 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Thorpe, H.; Wheaton, B. The Olympic Games, Agenda 2020 and action sports: The promise, politics and performance of organisational change. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2019, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, M.; Haizinger, L. Does the Olympic Agenda 2020 Have the Power to Create a New Olympic Heritage? An Analysis for the 2026 Winter Olympic Games Bid. Sustainability 2019, 11, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAloon, J. Agenda 2020 and the Olympic Movement. Sport Soc. 2016, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Session Approves Olympic Agenda 2020+5 as the Strategic Roadmap to 2025. Available online: https://www.olympic.org/news/ioc-session-approves-olympic-agenda-2020-5-as-the-strategic-roadmap-to-2025 (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. Olympic Agenda 2020+5. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/Olympic-agenda/Olympic-Agenda-2020-5-15-recommendations.pdf?_ga=2.201255596.386407540.1662285447-105845724.1620955608 (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Chappelet, J.-L. L’avenir des candidatures olympiques. Jurisport La Rev. Jurid. Et Économique Du Sport 2017, 177, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bovy, P. Rio 2016 Olympic Games public transport development outstanding legacy and mobility sustainability. In Working Paper; Mega Event Transport and Mobility: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kassens-Noor, E. Managing the Olympics; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, D.; Dickinson, J.; Calver, S. Planning transport for special events: A conceptual framework and future agenda for research. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H.; Andreff, W.; Weitzmann, M. Cost and Revenue Overruns of the Olympic Games 2000–2018, 3rd ed.; Springer Nature: Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Stewart, A.; Budzier, A. The Oxford Olympics Study 2016: Cost and Cost Overrun at the Games. Saïd Bus. Sch. Work. Pap. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. Legacy Strategic Approach Moving Forward. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/Documents/Olympic-Legacy/IOC_Legacy_Strategy_Full_version.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. 2022 Candidature Acceptance Procedure. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/Documents/Host-City-Elections/XXIV-OWG-2022/Candidature-Acceptance-Procedure-for-the-XXIV-Olympic-Winter-Games-2022.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. Beijing 2022 Committed to Hosting “Green, Inclusive, Open and Clean” Games. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/beijing-2022-committed-to-hosting-green-inclusive-open-and-clean-games (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- China Daily. On Course for ‘Streamlined, Safe and Splendid’ Games. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202107/23/WS60fa1626a310efa1bd663d86.html (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. Report of the 2022 Evaluation Commission. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/Documents/Host-City-Elections/XXIV-OWG-2022/Report-of-the-IOC-Evaluation-Commission-LR-for-the-XXIV-Olympic-Winter-Games-2022.pdf?_ga=2.193909933.1654414290.1666598151-105845724.1620955608 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. The IOC Stands in Solidarity with All Athletes and All Sports. Available online: https://www.olympic.org/news/the-ioc-stands-in-solidarity-with-all-athletes-and-all-sports (accessed on 23 September 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. Hundreds of Athletes Reach Beijing 2022 with Support from Olympic Solidarity. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/hundreds-of-athletes-reach-beijing-2022-with-support-from-olympic-solidarity (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Lesoleil. Thomas Bach, President Du Comite International Olympique: «Le Cio va Contribuer Pour 53 Milliards de FCfa». Available online: http://lesoleil.sn/thomas-bach-president-du-comite-international-olympique-le-cio-va-contribuer-pour-53-milliards-de-fcfa/ (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Olympic Broadcasting Services. Company Overview. Available online: https://www.obs.tv/organisation (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Olympic Broadingcasting Services. OBS and Beijing 2022 Celebrate a Major Milestone with the Official Handover of the International Broadcast Centre in Olympic Park. Available online: https://www.obs.tv/news/798 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Kim, H.-D. The 2012 London Olympics: Commercial Partners, Environmental Sustainability, Corporate Social Responsibility and Outlining the Implications. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2013, 30, 2197–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Olympic Committee. IOC Annual Report 2018. Available online: https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/Documents/IOC-Annual-Report/IOC-ANNUAL-REPORT-2018.pdf?_ga=2.142591986.1344564548.1660707905-105845724.1620955608 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- International Olympic Committee. The Vancouver Debrief in Sochi. Available online: https://olympics.com/ioc/news/the-vancouver-debrief-in-sochi/91229 (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Giddens, A.; Sutton, P.W. Essential Concepts in Sociology, 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Orders of discourse. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1971, 10, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Edition | Year | Quantity | Candidate Cities (the First Being the Elected Host City) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 1948 | 1 | London |

| 15 | 1952 | 9 | Helsinki, Amsterdam, Athens, Lausanne, Stockholm, Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, Minneapolis |

| 16 | 1956 | 10 | Melbourne, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Montreal, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Chicago |

| 17 | 1960 | 15 | Rome, Athens, Brussels, Budapest, Buenos Aires, Lausanne, Rio, Tokyo, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, New York, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Chicago |

| 18 | 1964 | 5 | Tokyo, Brussels, Vienna, Buenos Aires, Detroit |

| 19 | 1968 | 4 | Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Detroit, Lyon |

| 20 | 1972 | 4 | Munich, Montreal, Madrid, Detroit |

| 21 | 1976 | 4 | Montreal, Los Angeles, Moscow, Florence |

| 22 | 1980 | 2 | Moscow, Los Angeles |

| 23 | 1984 | 1 | Los Angeles |

| 24 | 1988 | 2 | Seoul, Nagoya |

| 25 | 1992 | 6 | Barcelona, Paris, Belgrade, Brisbane, Birmingham, Amsterdam |

| 26 | 1996 | 6 | Atlanta, Athens, Toronto, Melbourne, Manchester, Belgrade |

| 27 | 2000 | 5 | Sydney, Beijing, Berlin, Manchester, Istanbul |

| 28 | 2004 | 5 | Athens, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Rome, Stockholm |

| 29 | 2008 | 5 | Beijing, Toronto, Istanbul, Paris, Osaka |

| 30 | 2012 | 5 | London, Paris, Madrid, New York, Moscow |

| 31 | 2016 | 4 | Rio, Madrid, Tokyo, Chicago |

| 32 | 2020 | 3 | Tokyo, Istanbul, Madrid |

| 33 | 2024 | 2 | Paris, Los Angeles |

| Venues | Beijing 2008 | Beijing 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| National Aquatics Centre | Swimming | Curling |

| National Indoor Stadium | Gymnastics, handball, etc. | Ice Hockey |

| Wukesong Sports Centre | Basketball | Ice Hockey |

| Capital Indoor Stadium | Volleyball | Short-Track Speed Skating, Figure Skating |

| National Speed Skating Oval | Temporary venue for hockey and archery | Speed Skating |

| National Stadium | Opening and closing ceremonies, athletics | Opening and closing ceremonies |

| National Convention Centre | Main press centre | Main media centre |

| OG | Teams | Athletes |

|---|---|---|

| Beijing 2008 | 204 | 10,942 |

| London 2012 | 204 | 10,568 |

| Rio 2016 | 207 | 11,238 |

| Tokyo 2020 | 206 | 11,420 |

| OWG | Teams | Athletes |

|---|---|---|

| Vancouver 2010 | 82 | 2566 |

| Sochi 2014 | 88 | 2780 |

| PyeongChang 2018 | 92 | 2833 |

| Beijing 2022 | 91 | 2834 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, W.; Xu, N.; Xue, R.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ren, D. Efforts Proposed by IOC to Alleviate Pressure on Olympic Games Hosts and Evidence from Beijing 2022. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316086

Yan W, Xu N, Xue R, Ye Z, Wang Z, Ren D. Efforts Proposed by IOC to Alleviate Pressure on Olympic Games Hosts and Evidence from Beijing 2022. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):16086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316086

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Weihua, Na Xu, Rui Xue, Zhenghang Ye, Zhaoyang Wang, and Dingmeng Ren. 2022. "Efforts Proposed by IOC to Alleviate Pressure on Olympic Games Hosts and Evidence from Beijing 2022" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 16086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316086

APA StyleYan, W., Xu, N., Xue, R., Ye, Z., Wang, Z., & Ren, D. (2022). Efforts Proposed by IOC to Alleviate Pressure on Olympic Games Hosts and Evidence from Beijing 2022. Sustainability, 14(23), 16086. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142316086