One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure: Negative Experiences of Tourists with Different Satisfaction Levels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Complex Connotation of Tourist Experience

2.2. Negative Experience in Tourism Context

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

- (1)

- After reading all the reviews, two individuals familiar to the study preprocess the data with the assisted of Leximancer. Non-lexical and weak semantic information (such as “I’m”, “the”, “of”, and “on”) are removed [39]. The concept seeds are adjusted by merging similar concepts (e.g., the singular and plural forms of nouns) and defining new concepts not included in the thesaurus (e.g., Lijiang, Naxi).

- (2)

- Use Leximancer to calculate the data. Visual concept maps and statistical outputs are generated. A concept map (Topical map) to quantify the relationships between concepts is generated to help identifying the themes of tourist experience.

- (3)

- Classify the reviews into three categories (low satisfaction with the rating of 1 or 2, medium satisfaction with the rating of 3, and high satisfaction with the rating of 4 or 5). Recalculate the data of low satisfaction and high satisfaction reviews.

3.4. Reliability and Validity Assessment

4. Results

4.1. Concept Map

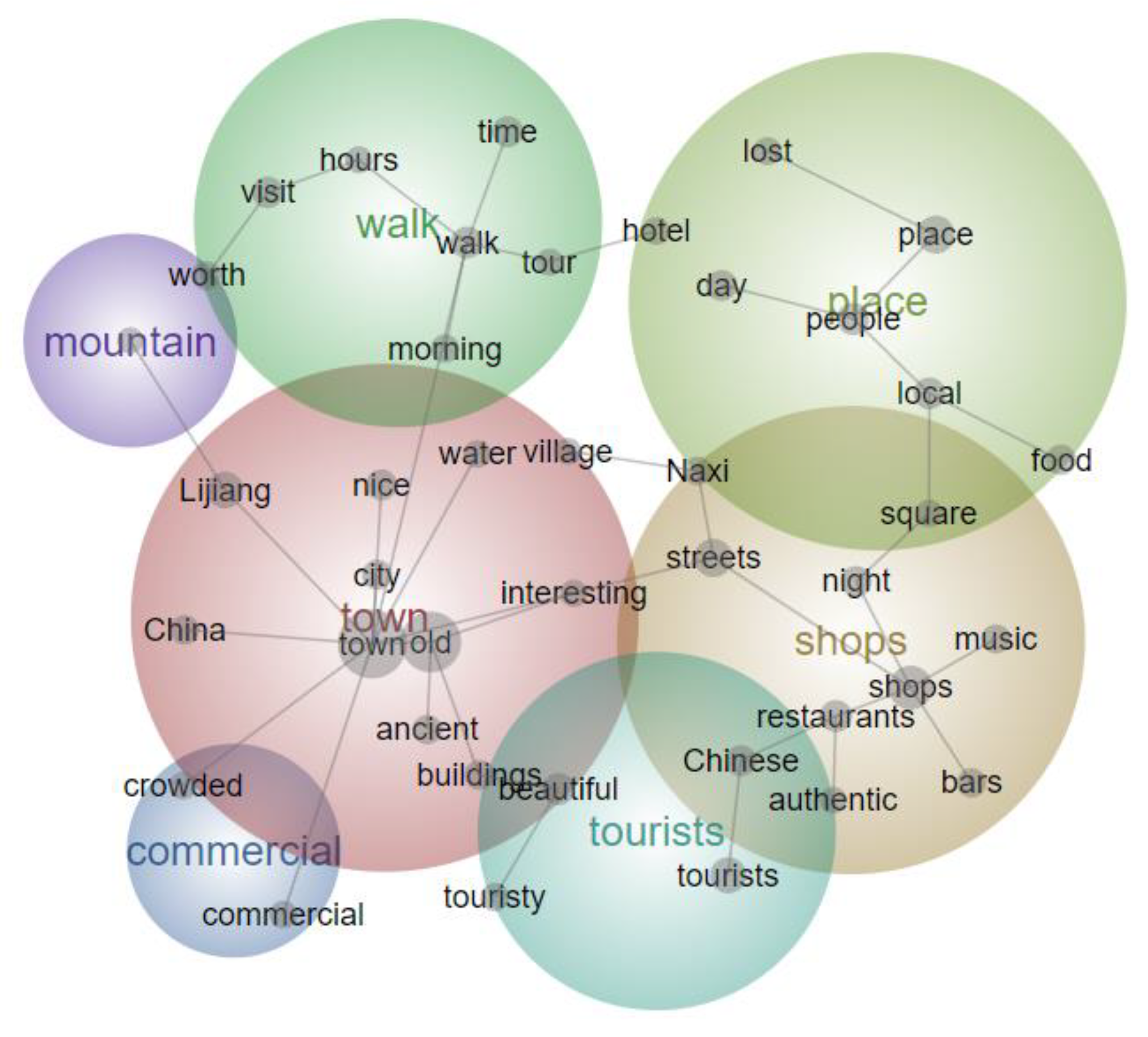

4.1.1. Overall Experience of the Tourists

- (1)

- General impression of the town: This is the most mentioned theme. The included concepts are mainly related to the overall impression of Lijiang (China, Lijiang, town, city old, ancient, nice, interesting, and beautiful) and the most representative elements in the town (buildings and water).

- (2)

- Sites in the town—shops: This theme contains concepts related to the sites in the old town (shops, restaurants, bars, streets, and squares) and tourists’ experience of these sites (music in the shops, authenticity of the old town, Naxi culture, and activities at night).

- (3)

- Activities—place: This theme contains concepts related to tourist activities (places to visit, people to meet, local food to taste in the square, and getting lost in the old town). Additionally, these activities require tourists to interact with the external environment to a good experience.

- (4)

- Visiting the quiet old town—walk. Unlike the ordinary tourism activities covered by the previous theme, the concepts mainly include tourists’ efforts to become familiar with the authentic old town (take time and walk around the town in the morning hours, then you will find it is worth taking a tour (visit)).

- (5)

- Touristy aspects—tourists. This theme mainly focuses on comments about the touristy aspects of Lijiang Old Town. The most mentioned point is that there are a lot of Chinese tourists in the old town.

- (6)

- Commercialization—commercial. This theme contains negative concepts about Lijiang’s commercialization and crowding.

- (7)

- Nature landscape—mountains. This theme has only one concept (mountains), which refers to the natural landscape around the Old Town of Lijiang.

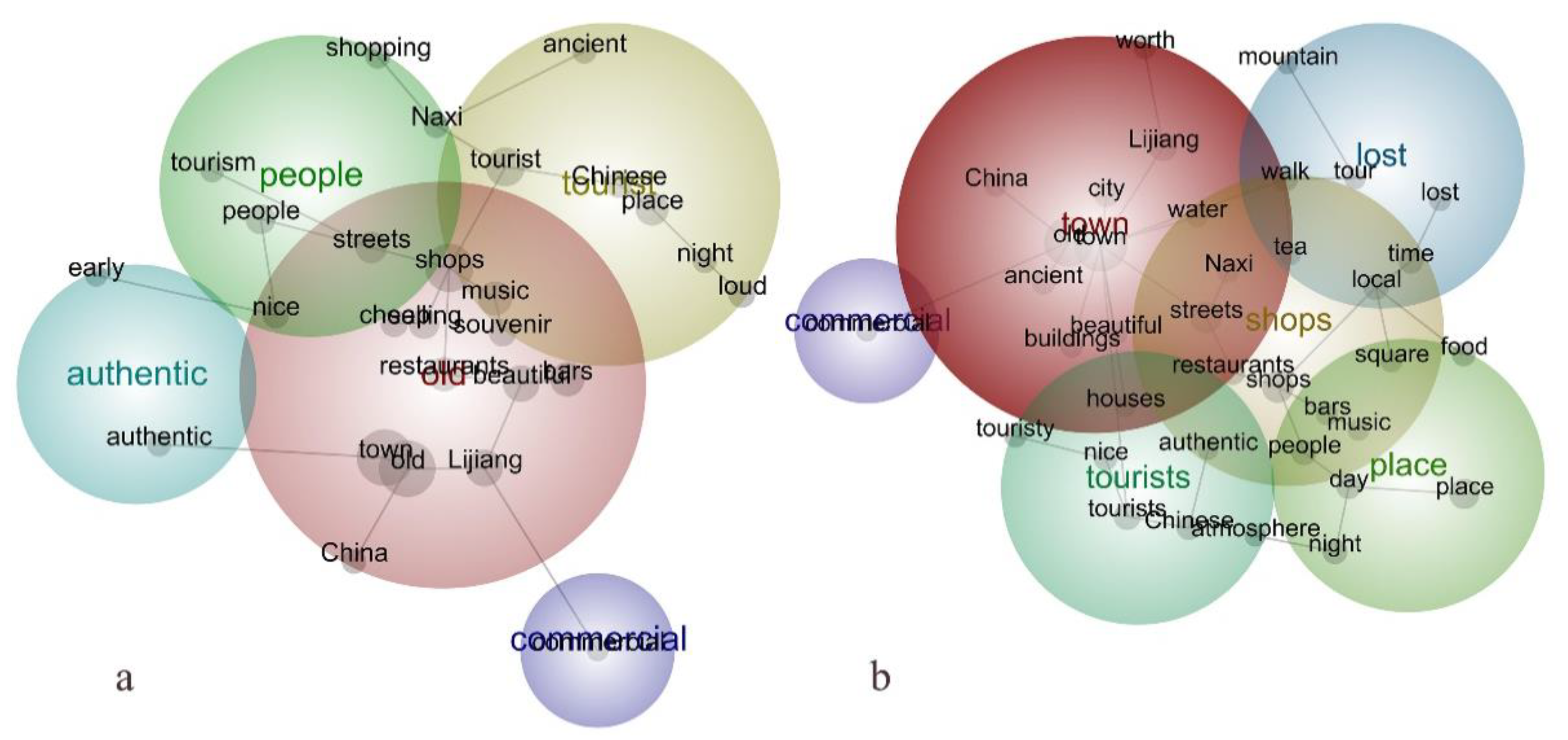

4.1.2. The Concept Map of Tourists with High and Low Satisfaction

4.2. Themes of Negative Experiences

4.2.1. Commercialization and Touristy Aspects

“All you can find in this place is chaos and tourists—thousands of generic bars or shops that have nothing ‘local’ in them.”

“Way too commercialized, crowded, dirty and loud with bars competing in noise to attract customers.” (Low satisfaction)

“Like what other reviewers said, it’s a bit over commercialized but I do find some little corners, the streams and the inns quite nicely designed and fun place to spend some time.” (High satisfaction)

“The big problem is that it is becoming too touristy. It is full of identical shops and the main streets are packed in the evenings and full of loud bars.” (Low satisfaction)

“It also has the absolute noisiest bars and restaurants which attracts numerous youngsters—but don’t be put off by this as it really does add to its atmosphere.” (High satisfaction)

4.2.2. Lack of Authenticity

“Lijiang and other cities in the area are disappointing. It’s not anymore authentic China, it’s Chinese tourism.” (Low satisfaction)

“The local market is very authentic, with villagers selling all sorts of produce, including a seemingly endless array of dried herbs and mushrooms.” (High satisfaction)

“I have to admit that it’s well preserved, the streets and buildings are nice to look at—but only very early in the morning when everyone is still asleep.” (Low satisfaction)

“Lijiang is a must see, but best if you can avoid the tourists, e.g., early mornings, when you can see more real life.” (High satisfaction)

4.2.3. Easy to Get Lost

“Getting lost in the maze of streets and alleys of this town within a town is easy, and a most enjoyable process. There are, of course, a great number of tourists, but this need not detract one from the overall happy experience of wandering the streets and checking out its variety of shops and cafes…” (High satisfaction)

“Perhaps our favorite part of the old town was how it was possible to discover a new alleyway or tiny bridge with each turn. At times it was very confusing trying to find our way, but we were always rewarded with a pretty site whenever we got lost.” (High satisfaction)

“It is suggested that tourists do not leave their hotel without taking their hotel card with them. Tourists can easily get lost and struggle to find anyone who speaks English to help them with directions back to their hotel.”

“A useful tip I learnt from my driver was that one will never get lost in the city simply by remembering this golden rule. Follow the direction of the water flowing and it leads one into the city and against the flow of the water will lead one out of the city. I can testify it is true!”

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, H.; So, K.K.F. Two decades of customer experience research in hospitality and tourism: A bibliometric analysis and thematic content analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Jozić, D.; Kuehnl, C. Customer experience management: Toward implementing an evolving marketing concept. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J.; Zhang, T.; Jaakkola, E. Customer experience management in hospitality: A literature synthesis, new understanding and research agenda. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience Throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhshik, A.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Ozturen, A.; Ramkissoon, H. Memorable tourism experiences and critical outcomes among nature-based visitors: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G.; van der Veen, R.; Huang, S.; Deesilatham, S. Mediating Effects of Place Attachment and Satisfaction on the Relationship between Tourists’ Emotions and Intention to Recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limberger, P.F.; Dos Anjos, F.A.; de Souza Meira, J.V.; dos Anjos, S.J.G. Satisfaction in hospitality on tripadvisor. Com: An analysis of the correlation between evaluation criteria and overall satisfaction. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2014, 10, 59–65. Available online: http://www.tmstudies.net/index.php/ectms/article/download/648/1156 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Schmitt, B. Experiential Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Perceived quality and service experience: Mediating effects of positive and negative emotions. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. Tourist Inspiration: How the Wellness Tourism Experience Inspires Tourist Engagement. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 10963480211026376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Otoo, F.E.; Suntikul, W.; Huang, W.-J. Understanding culinary tourist motivation, experience, satisfaction, and loyalty using a structural approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Wasan, P. Positioning of tourist destinations in the digital era: A review of online customer feedback. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. Bloggers’ reported tourist experiences: Their utility as a tourism data source and their effect on prospective tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 16, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, T.; Zhang, E.Y. Analysis of Blogs and Microblogs: A Case Study of Chinese Bloggers Sharing Their Hong Kong Travel Experiences. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, M.; Fangying, C.; Shuzhen, P. Influence of online comments on tourist’purchase intention based on questionnaire survey among tourists in Tai’an city. J. Landsc. Res. 2016, 8, 52–54. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/01e0bb724545ba1d00073aeea3f0e2aa/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1596366 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Aggarwal, S.; Gour, A. Peeking inside the minds of tourists using a novel web analytics approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoab, Q.; Zhaiab, X. “I will never go to Hong Kong again!” How the secondary crisis communication of “Occupy Central” on Weibo shifted to a tourism boycott. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K. Branding Thailand: Correcting the negative image of sex tourism. Place Brand. Public Dipl. 2007, 3, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Demystifying the effects of perceived risk and fear on customer engagement, co-creation and revisit intention during COVID-19: A protection motivation theory approach. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. The Case Study as a Serious Research Strategy. Knowledge 1981, 3, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotto, F.L.; Zanni, P.P.; De Moraes, G.H.S.M. What is the use of a single-case study in management research? Rev. De Adm. De Empresas 2014, 54, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation Methods; Sage Publications, Inc.: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980; Available online: https://scholar.google.com.hk/scholar?hl=zh-N&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Qualitative+Evaluation+Methods+Beverly+Hills+Patton&btnG= (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Xu, H.; Ye, T. Dynamic destination image formation and change under the effect of various agents: The case of Lijiang, ‘The Capital of Yanyu’. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. The Imagination of Place and Tourism Consumption: A Case Study of Lijiang Ancient Town, China. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Urban conservation in Lijiang, China: Power structure and funding systems. Cities 2010, 27, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, A. Analysis of travel bloggers’ characteristics and their communication about austria as a tourism destination. J. Vacat. Mark. 2008, 14, 169–176. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/palgrave.pb.6000045 (accessed on 29 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. User-Generated Content as a Research Mode in Tourism and Hospitality Applications: Topics, Methods, and Software. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Gretzel, U. Role of social media in online travel information search. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, D.L. Theory, Method, and Practice in Computer Content Analysis. Computer-Assisted Content Analysis. 2001. Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=OuDS1XoIyhUC&oi=fnd&pg=PA13&d (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Pearce, P.L.; Wu, M.-Y. Entertaining International Tourists: An Empirical Study of an Iconic Site in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 772–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.E.; Humphreys, M.S. Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behav. Res. Methods 2006, 38, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, T.; Carey, G.; Kjartansson, R. A multiple software approach to understanding values. J. Beliefs Values 2010, 31, 283–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Automatic extraction of semantic networks from text using leximancer. In Proceedings of the HLT-NAACL 2003 Demonstrations, Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 31 May 2003; The University of Queensland: St Lucia, QLD, Australia, 2003. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/N03-4012.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Cheng, M.; Edwards, D. A comparative automated content analysis approach on the review of the sharing economy discourse in tourism and hospitality. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriadou, P.; Brouwers, J.; Le, T.-A. Choosing a qualitative data analysis tool: A comparison of NVivo and Leximancer. Ann. Leis. Res. 2014, 17, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, D.; Rintel, S.; Wiles, J. Making sense of big text: A visual-first approach for analysing text data using Leximancer and Discursis. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2013, 16, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.; Wu, B.; Morrison, A.M.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.-C. Travel blogs on China as a destination image formation agent: A qualitative analysis using Leximancer. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Y.; Wall, G.; Pearce, P. Shopping experiences: International tourists in Beijing’s Silk Market. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipf, G. Selected Studies of the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J.; Bracken, C.C. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S. Meta-analysis of cohen’s kappa. Health Serv. Outcomes Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 145–163. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10742-011-0077-3 (accessed on 29 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Su, X. Studies on tourism commercialization in historic towns. Acta Geogr. Sin.-Chin. Ed. 2004, 59, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passini, R. Wayfinding design: Logic, application and some thoughts on universality. Des. Stud. 1996, 17, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Staging tourism: Tourists as performers. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 322–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J., II; Gilmore, J.H. Welcome to the experience economy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Wang, Y.; Song, H. Understanding the causes of negative tourism experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The Impact of Memorable Tourism Experiences on Loyalty Behaviors: The Mediating Effects of Destination Image and Satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 856–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, I.; Ritchie, G.; Tourism, J. Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. The antecedents of memorable tourism experiences: The development of a scale to measure the destination attributes associated with memorable experiences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 44, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Brien, A.; Primiana, I.; Wibisono, N.; Triyuni, N.N. Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Turner, L. Cross-Cultural Behaviour in Tourism. Routledge. 2012. Available online: https://cris.bgu.ac.il/en/publications/cross-cultural-behaviour-in-tourism-concepts-and-analysis (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Li, L.; Zhang, J.; Nian, S.; Zhang, H. Tourists’ perceptions of crowding, attractiveness, and satisfaction: A second-order structural model. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, F.; Ryan, C. Jazz and knitwear: Factors that attract tourists to festivals. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, M. Positive and Negative Urban Tourist Crowding: Florence, Italy. Tour. Geogr. 2012, 14, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebat, J.-C.; Gélinas-Chebat, C.; Therrien, K. Lost in a mall, the effects of gender, familiarity with the shopping mall and the shopping values on shoppers’ wayfinding processes. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1590–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H. Which one helps tourists most? Perspectives of international tourists using different navigation aids. Tour. Geogr. 2015, 17, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.H.; Anderson, L.A.; Belza, B.L. (Eds.) Community Wayfinding: Pathways to Understanding; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.K.; Dawson, C.P. An Exploratory Study of the Complexities of Coping Behavior in Adirondack Wilderness. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, R.E.; Valliere, W.A. Coping in Outdoor Recreation: Causes and Consequences of Crowding and Conflict Among Community Residents. J. Leis. Res. 2001, 33, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, S.; Beckenuyte, C.; Butt, M.M. Consumers’ behavioural intentions after experiencing deception or cognitive dissonance caused by deceptive packaging, package downsizing or slack filling. Eur. J. Mark. 2016, 50, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, A.; Yuksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Concept | Freq. | Rank | Concept | Freq. | Rank | Concept | Freq. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | towns | 1487 | 15 | people | 287 | 29 | worth | 141 |

| 2 | old | 1439 | 16 | beautiful | 269 | 30 | music | 136 |

| 3 | shops | 881 | 17 | Chinese | 266 | 31 | Naxi | 133 |

| 4 | Lijiang | 677 | 18 | nights | 262 | 32 | mountain | 129 |

| 5 | streets | 510 | 19 | restaurants | 258 | 33 | square | 119 |

| 6 | buildings | 502 | 20 | city | 234 | 34 | lost | 116 |

| 7 | visit | 462 | 21 | China | 230 | 35 | interesting | 111 |

| 8 | place | 451 | 22 | day | 227 | 36 | crowded | 100 |

| 9 | tourists | 445 | 23 | nice | 216 | 37 | authentic | 93 |

| 10 | time | 319 | 24 | bar | 202 | 38 | morning | 89 |

| 11 | walk | 308 | 25 | water | 191 | 39 | hours | 86 |

| 12 | local | 298 | 26 | ancient | 187 | 40 | tour | 83 |

| 13 | food | 298 | 27 | touristy | 162 | 41 | villages | 75 |

| 14 | night | 293 | 28 | commercial | 150 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, S. One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure: Negative Experiences of Tourists with Different Satisfaction Levels. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315964

Li L, Zhuang Y, Gao Y, Li S. One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure: Negative Experiences of Tourists with Different Satisfaction Levels. Sustainability. 2022; 14(23):15964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315964

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Li, Yaoming Zhuang, Yanpeng Gao, and Shasha Li. 2022. "One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure: Negative Experiences of Tourists with Different Satisfaction Levels" Sustainability 14, no. 23: 15964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315964

APA StyleLi, L., Zhuang, Y., Gao, Y., & Li, S. (2022). One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure: Negative Experiences of Tourists with Different Satisfaction Levels. Sustainability, 14(23), 15964. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315964