Which Is More Concerning for Accounting Professionals-Personal Risk or Professional Risk?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Risk and Risk Aversion

“1. Risk is the possibility of an unfortunate occurrence2. Risk is the potential for the realization of unwanted, negative consequences of an event3. Risk is exposure to a proposition (e.g., the occurrence of a loss) of which one is uncertain4. Risk is the consequences of the activity and associated uncertainties5. Risk is uncertainty about and severity of the consequences of activity for something that humans value6. Risk is the occurrences of some specified consequences of the activity and associated uncertainties7. Risk is the deviation from a reference value and associated uncertainties”.[31]

2.2. Personal Risk and Professional Risk

2.3. Factors Influencing Individuals’ Risk Aversion

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. The Questionnaire

4. Findings and Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knight, F.H. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Ackert, L.; Deaves, R. Behavioral Finance: Psychology, Decision-Making, and Markets; Cengage Learning: Toronto, ON, Canada; Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 1–383. [Google Scholar]

- Cory, S.N. Quality and quantity of accounting students and the stereotypical accountant: Is there a relationship? J. Account. Educ. 1992, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.H. The credit man and the public accountant. J. Account. 1906, 1, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Sunder, S. Risk in accounting. Abacus 2015, 51, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R. Conservatism, prudence and the IASB’s conceptual framework. Account. Bus. Res. 2015, 45, 514–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, G.; Hamlin, A. Analytic conservatism. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 2004, 34, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, B.; Hasan, I.; Park, J.C.; Wu, Q. Gender differences in financial reporting decision making: Evidence from accounting conservatism. Contemp. Account. Res. 2015, 32, 1285–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartog, J.; Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A.; Jonker, N. Linking measured risk aversion to individual characteristics. Kyklos 2002, 55, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoitash, R.; Hoitash, U.; Kurt, A.C. Do accountants make better chief financial officers? J. Account. Econ. 2016, 61, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennox, C.S.; Kausar, A. Estimation risk and auditor conservatism. Rev. Account. Stud. 2017, 22, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliar, C.V.; Lonie, A.A.; Power, D.M.; Sinclair, C.D. Managerial attitudes to risk: A comparison of Scottish chartered accountants and UK managers. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2002, 11, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellaportas, S. Conversations with inmate accountants: Motivation, opportunity and the fraud triangle. Account. Fórum 2013, 37, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Molla Imeny, V.; Khaleghi Baygi, A. The necessity of anti-money laundering standards for Iranian auditors. J. Money Laund. Control 2020, 23, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toms, S. Financial scandals: A historical overview. Account. Bus. Res. 2019, 49, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, R.N. Computer fraud—A management trap: Risks are legal, economic, professional. Bus. Horiz. 1969, 12, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Han, X.; Shen, H.; Xing, Q. Do professional risk funds affect audit quality? Account. Bus. Res. 2021, 51, 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, T.; Shachat, J. The development of risk aversion and prudence in Chinese children and adolescents. J. Risk Uncertain. 2020, 61, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzakis, E.; Sadeh, J. Experimental evidence on the effect of incentives and domain in risk aversion and discounting tasks. J. Risk Uncertain. 2021, 62, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency-International. Corruption Perceptions Index 2021; Transparency-International: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Molla Imeny, V.; Norton, S.D.; Moradi, M.; Salehi, M. The anti-money laundering expectations gap in Iran: Auditor and judiciary perspectives. J. Money Laund. Control 2021, 24, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, B.A. Definitions of risk. J. Dent. Educ. 2001, 65, 1007–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, R.C.; McGuigan, J.R.; Rao, R.P. Contemporary Financial Management; Cengage Learning: Stamford, CT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, R. Environmental Decision-Making: The Roles of Scientists, Engineers, and the Public; Illustrated, Reprint; Federation Press: Alexandria, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff, B.; Watson, S.R.; Hope, C. Defining risk. Policy Sci. 1984, 17, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomkvist, A. Psychological aspects of values and risks. Risk Soc. 1987, 6, 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, K. The Study of Risk in Social Systems: An Anthropological Perspective—Risk and Society: Studies of Risk Generation and Reactions to Risk; Allen and Unwin: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J. Risk; Taylor & Francis: London, UK; University College London: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC. ISO/IEC Guide 63: Guide to the Development and Inclusion of Aspects of Safety in International Standards for Medical Devices; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Selvik, J.T.; Abrahamsen, E.B. Explicit and implicit inclusion of time in the definitions of risk and reliability. Saf. Reliab. 2021, 40, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SRA. Society for Risk Analysis Glossary; Society of Risk Analysis: Herndon, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bodie, Z.; Kane, A.; Marcus, A.J. Investments, 12th ed.; Irwin/McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, S.; Wiesen, D. Joint measurement of risk aversion, prudence, and temperance. J. Risk Uncertain. 2014, 48, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabner, I. Risk takers. In International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences; Macmillan Reference: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, G.W.; Elisabet Rutström, E. Risk Aversion in the Laboratory. Risk Aversion Exp. 2008, 12, 41–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, U.; Zank, H. What is loss aversion? J. Risk Uncertain. 2005, 30, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, W.T.; Peffer, S.A. Beliefs about accountants’ risk tendencies and their effect on the integration of accountants’ advice regarding expenditure decisions. In Proceedings of the American Accounting Association’s 2008 MAS Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, 3–8 August 2008; Working paper. American Accounting Association’s: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muasya, A.M. The Relationship between Credit Risk Management Practices and Loans Losses–A Study on Commercial Banks in Kenya. Master’s Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, S.; Davidowitz, B.; Maughan, P. Developing professional competence in accounting graduates: An action research study. S. Afr. J. Account. Res. 2020, 34, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, O.; Holm, H.J.; Tyran, J.R.; Wengström, E. Robust inference in risk elicitation tasks. J. Risk Uncertain. 2020, 61, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliera, A.; Rutström, E.E. Crowded out: Heterogeneity in risk attitudes among poor households in the US. J. Risk Uncertain. 2021, 63, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Treich, N. Optimality of winner-take-all contests: The role of attitudes toward risk. J. Risk Uncertain. 2021, 63, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U.; Blais, A.R.; Betz, N.E. A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2002, 15, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp Jonathan, P.; David, C.; Magnus, J. The Psychometric and Empirical Properties of Measures of Risk Preferences. J. Risk Uncertain. 2017, 54, 203–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, N.; Shane, S. Common genetic effects on risk-taking preferences and choices. J. Risk Uncertain. 2019, 59, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J. Determinants of risk-taking: Behavioral and economic views. J. Risk Uncertain. 1993, 6, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.W.; Morgan, M.G.; Fischhoff, B.; Nair, I.; Lave, L.B. What risks are people concerned about. Risk Anal. 1991, 11, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, W.C. The Brand and Growth Strategies of Online Food Delivery in Taiwan. Bachelor’s Thesis, Wenzao Ursuline University of Languages, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, A.J.; Klein, W.M.; Weinstein, N.D. Absolute and relative biases in estimations of personal risk. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 26, 1213–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, L. The different dynamics of personal and general risk. Risk Manag. 2003, 5, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D.; Bain, A. Professional Risk and Working with People: Decision-Making in Health, Social Care and Criminal Justice; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar]

- Ishaque, M. Managing conflict of interests in professional accounting firms: A research synthesis. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 169, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, J.; Alam, M.M.; Karim, Z.A.; Johari, R.J. Integrating religiosity into fraud triangle theory: Findings on Malaysian police officers. J. Criminol. Res. Policy Pract. 2018, 4, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilleholt, L. Cognitive ability and risk aversion: A systematic review and meta analysis. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2019, 14, 234–279. [Google Scholar]

- Charness, G.; Gneezy, U. Strong evidence for gender differences in risk taking. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 83, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defoe, I.N.; Dubas, J.S.; Figner, B.; van Aken, M.A. A meta-analysis on age differences in risky decision making: Adolescents versus children and adults. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 48–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noussair, C.N.; Trautmann, S.T.; van de Kuilen, G.; Vellekoop, N. Risk aversion and religion. J. Risk Uncertain. 2013, 47, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halek, M.; Eisenhauer, J.G. Demography of risk aversion. J. Risk Insur. 2001, 68, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, C. Risk aversion and sorting into public sector employment. Ger. Econ. Rev. 2011, 12, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, C.; Musumeci, R. Linking risk aversion and type of employment. J. Socio-Econ. 2011, 40, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaita, A.; Stürmer, K. Risk aversion and the teaching profession: An analysis including different forms of risk aversion, different control groups, selection and socialization effects. Educ. Econ. 2020, 28, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q. Does nurture matter: Theory and experimental investigation on the effect of working environment on risk and time preferences. J. Risk Uncertain. 2011, 43, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.S.; Hong, F. Risk breeds risk aversion. Exp. Econ. 2018, 21, 815–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardies, K.; Breesch, D.; Branson, J. Gender differences in overconfidence and risk taking: Do self-selection and socialization matter? Econ. Lett. 2013, 118, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Shafie, R.; Ku Ismail, K.N.I. CFO attributes and accounting conservatism: Evidence from Malaysia. Pac. Account. Rev. 2021, 33, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.W.; Previts, G.J. The risk preference profiles of practising CPAs: Some tentative results. Account. Bus. Res. 1982, 13, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellante, D.; Link, A.N. Are public sector workers more risk averse than private sector workers? ILR Rev. 1981, 34, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, T.C.; Sharp, N.Y.; Wang, D. The impact of religion on the going concern reporting decisions of local audit offices. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical-Centre-of-Iran. Iran Statistical Yearbook 1397 (2018–2019). 2019. Available online: https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Iran-Statistical-Yearbook (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Noida, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gärtner, M.; Mollerstrom, J.; Seim, D. Individual risk preferences and the demand for redistribution. J. Public Econ. 2017, 153, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsang, E.; Dohmen, T. Risk attitude and cognitive ageing. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 112, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahlíková, J.; Cingl, L. Risk preferences under acute stress. Exp. Econ. 2017, 20, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.L.; Katic, P. Cognitive skills, gender and risk preferences. Econ. Rec. 2013, 89, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.S.; Hoffmann, J.P. Risk and religion: An explanation of gender differences in religiosity. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1995, 34, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maung, M.; Tang, Z.; Wilson, C.; Xu, X. Religion, risk aversion, and cross border mergers and acquisitions. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money 2021, 70, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables. | Related Researches | Tested Sign | Expected Sign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Lilleholt [54]; Charness and Gneezy [55]; Noussair et al. [57]; Halek and Eisenhauer [58]; Hardies et al. [64] | +/− | − |

| Age | Lilleholt [54]; Defoe et al. [56]; Noussair et al. [57]; Halek and Eisenhauer [58]; Ismail et al. [65]; Martin and Previts [66] | +/− | + |

| Welfare | Noussair et al. [57]; Halek and Eisenhauer [58]; Hartog et al. [9] | +/− | − |

| Work experience | Ayaita and Stürmer [61]; Nguyen [62] | +/− | + |

| Job | He and Hong [63]; Halek and Eisenhauer [58] | + | |

| Working sector | Halek and Eisenhauer [58]; Pfeifer [59]; Bellante and Link, [67] | + | + |

| Religiosity | Noussair et al. [57]; Halek and Eisenhauer [58]; Omer et al. [68] | +/− | + |

| Panel A: Frequency and Percentage of Nominal Scale Variables | ||||||||

| Gender | Job | Working Sector | ||||||

| Freq | Percent | Freq | Percent | Freq | Percent | |||

| Category 1 | 159 | 32.6 | 243 | 49.9 | 303 | 62.2 | ||

| Category 2 | 328 | 67.4 | 208 | 42.7 | 184 | 37.8 | ||

| Category 3 | 36 | 7.4 | ||||||

| 487 | 100 | 487 | 100 | 487 | 100 | |||

| Panel B: Main Statistics of Demographic Variables | ||||||||

| Variable | N | Mean | Med | Std | SK | Kurt | Min | Max |

| Gender | 487 | 1.670 | 2.000 | 0.470 | −0.740 | −1.450 | 1 | 2 |

| Age | 487 | 36.280 | 34.000 | 8.710 | 1.170 | 1.260 | 20 | 68 |

| Work experience | 465 | 11.810 | 10.000 | 8.730 | 1.220 | 1.180 | 1 | 46 |

| Job | 487 | 1.570 | 2.000 | 0.630 | 0.620 | −0.570 | 1 | 3 |

| Working sector | 487 | 1.380 | 1.000 | 0.480 | 0.510 | −1.750 | 1 | 2 |

| Religiosity | 487 | 4.480 | 5.000 | 1.620 | −0.500 | −0.390 | 1 | 7 |

| Welfare | 487 | 3.940 | 4.000 | 1.010 | −0.500 | 0.640 | 1 | 7 |

| Panel A: Main Statistics of the Participants’ Beliefs about Their Personal and Professional Risk Aversion | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Med | Std | SK | Kurt | Min | Max | |

| Personal risk aversion | 487 | 3.970 | 4.000 | 1.390 | 0.110 | −0.430 | 1 | 1 |

| Professional risk aversion | 487 | 3.830 | 4.000 | 1.500 | 0.170 | −0.690 | 1 | 1 |

| Panel B: Main Statistics of the Participants’ Willingness to Perform Nine Risky Activities | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Med | Std | SK | Kurt | Min | Max | |

| Eating food four days past its eat-by date that appears to be still safe. | 487 | 1.910 | 1.000 | 1.390 | 1.740 | 2.360 | 1 | 7 |

| Walking across a meadow in which there are cattle, including a bull. | 487 | 2.120 | 2.000 | 1.380 | 1.320 | 1.080 | 1 | 7 |

| Participating in extreme sports such as rock climbing, parachute jumping, and wildwater rafting. | 487 | 2.010 | 1.000 | 1.370 | 1.560 | 2.270 | 1 | 7 |

| Agreeing to be a “Guinea pig” to test a new drug to combat a serious disease. | 487 | 1.780 | 1.000 | 1.330 | 1.960 | 3.290 | 1 | 7 |

| Taking up a new job and career which is entirely different from the one in which you have previously worked | 487 | 3.390 | 3.000 | 1.740 | 0.590 | −0.490 | 1 | 7 |

| Going camping in the wild. | 487 | 2.410 | 2.000 | 1.620 | 1.230 | 0.780 | 1 | 7 |

| Ignoring some persistent physical pain by not going to the doctor. | 487 | 3.040 | 3.000 | 1.690 | 0.670 | −0.390 | 1 | 7 |

| Speaking your mind about an unpopular issue on a social occasion. | 487 | 3.120 | 3.000 | 1.630 | 0.650 | −0.340 | 1 | 7 |

| Openly disagreeing with your boss in front of your coworkers. | 487 | 3.080 | 3.000 | 1.650 | 0.680 | −0.410 | 1 | 7 |

| Panel C: Main Statistics of the Participants’ Reaction to Two Risky Scenarios | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Med | Std | SK | Kurt | Min | Max | |

| Scenario 1 | 487 | 4.310 | 4.000 | 1.900 | −0.200 | −1.070 | 1 | 7 |

| Scenario 2 | 487 | 4.300 | 4.000 | 1.910 | −0.270 | −1.010 | 1 | 7 |

| Panel D: Main Statistics of the Participants’ Trade-off Between Personal and Professional Risks | ||||||||

| N | Mean | Med | Std | SK | Kurt | Min | Max | |

| Scenario 3 | 487 | 3.940 | 4.000 | 2.040 | −0.050 | −1.300 | 1 | 7 |

| Scenario 4 | 487 | 3.680 | 4.000 | 2.120 | 0.130 | −1.350 | 1 | 7 |

| Hypotheses | Null Hypothesis | Type of Test | Test Value | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | z-test | −0.411 | 0.340 | The null hypothesis is not rejected | |

| H2 | z-test | −2.172 | 0.014 | The null hypothesis is rejected | |

| H3 | z-test | −29.43 | 0.000 | The null hypothesis is rejected | |

| H4 | z-test | 4.105 | 0.000 | The null hypothesis is rejected | |

| H5 | z-test | 12.41 | 0.000 | The null hypothesis is rejected | |

| H6 | z-test | −4.426 | 0.000 | The null hypothesis is rejected | |

| H7 | z-test | −2.104 | 0.017 | The null hypothesis is rejected |

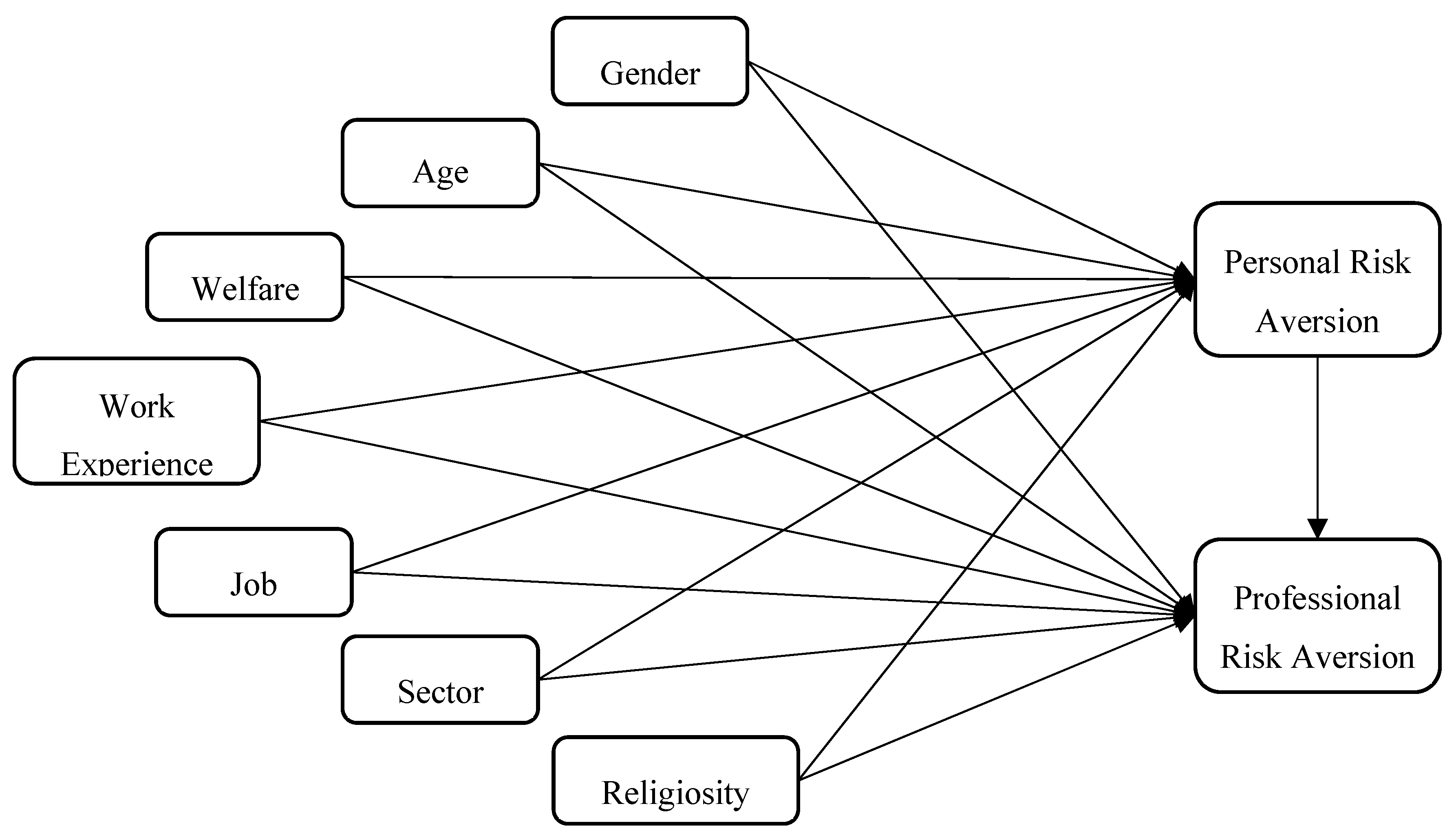

| The Path of Relationships | Coefficient | Std. Error | T-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age → Personal risk aversion | 0.042 | 0.112 | 1.316 | 0.752 |

| Age → Professional risk aversion | −0.007 | 0.129 | 0.058 | 0.954 |

| Gender → Personal risk aversion | 0.140 | 0.048 | 2.818 | 0.005 ** |

| Gender → Professional risk aversion | 0.125 | 0.052 | 2.369 | 0.018 * |

| Job → Personal risk aversion | −0.011 | 0.049 | 0.274 | 0.784 |

| Job → Professional risk aversion | −0.007 | 0.051 | 0.091 | 0.928 |

| Personal risk aversion → Professional risk aversion | 0.160 | 0.048 | 3.269 | 0.001 ** |

| Religiosity → Personal risk aversion | −0.142 | 0.048 | 2.887 | 0.004 ** |

| Religiosity → Professional risk aversion | −0.072 | 0.053 | 1.372 | 0.171 |

| Sector → Personal risk aversion | −0.003 | 0.055 | 0.099 | 0.921 |

| Sector → Professional risk aversion | −0.067 | 0.051 | 1.344 | 0.180 |

| Welfare → Personal risk aversion | 0.207 | 0.043 | 4.626 | 0.000 ** |

| Welfare → Professional risk aversion | 0.003 | 0.051 | 0.056 | 0.956 |

| Work experience → Personal risk aversion | −0.183 | 0.11 | 1.592 | 0.112 |

| Work experience → Professional risk aversion | −0.064 | 0.131 | 0.481 | 0.631 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Homayoun, S.; Imeny, V.M.; Salehi, M.; Moradi, M.; Norton, S. Which Is More Concerning for Accounting Professionals-Personal Risk or Professional Risk? Sustainability 2022, 14, 15452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215452

Homayoun S, Imeny VM, Salehi M, Moradi M, Norton S. Which Is More Concerning for Accounting Professionals-Personal Risk or Professional Risk? Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):15452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215452

Chicago/Turabian StyleHomayoun, Saeid, Vahid Molla Imeny, Mahdi Salehi, Mahdi Moradi, and Simon Norton. 2022. "Which Is More Concerning for Accounting Professionals-Personal Risk or Professional Risk?" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 15452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215452

APA StyleHomayoun, S., Imeny, V. M., Salehi, M., Moradi, M., & Norton, S. (2022). Which Is More Concerning for Accounting Professionals-Personal Risk or Professional Risk? Sustainability, 14(22), 15452. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215452