4.1. Discussion and Conclusions

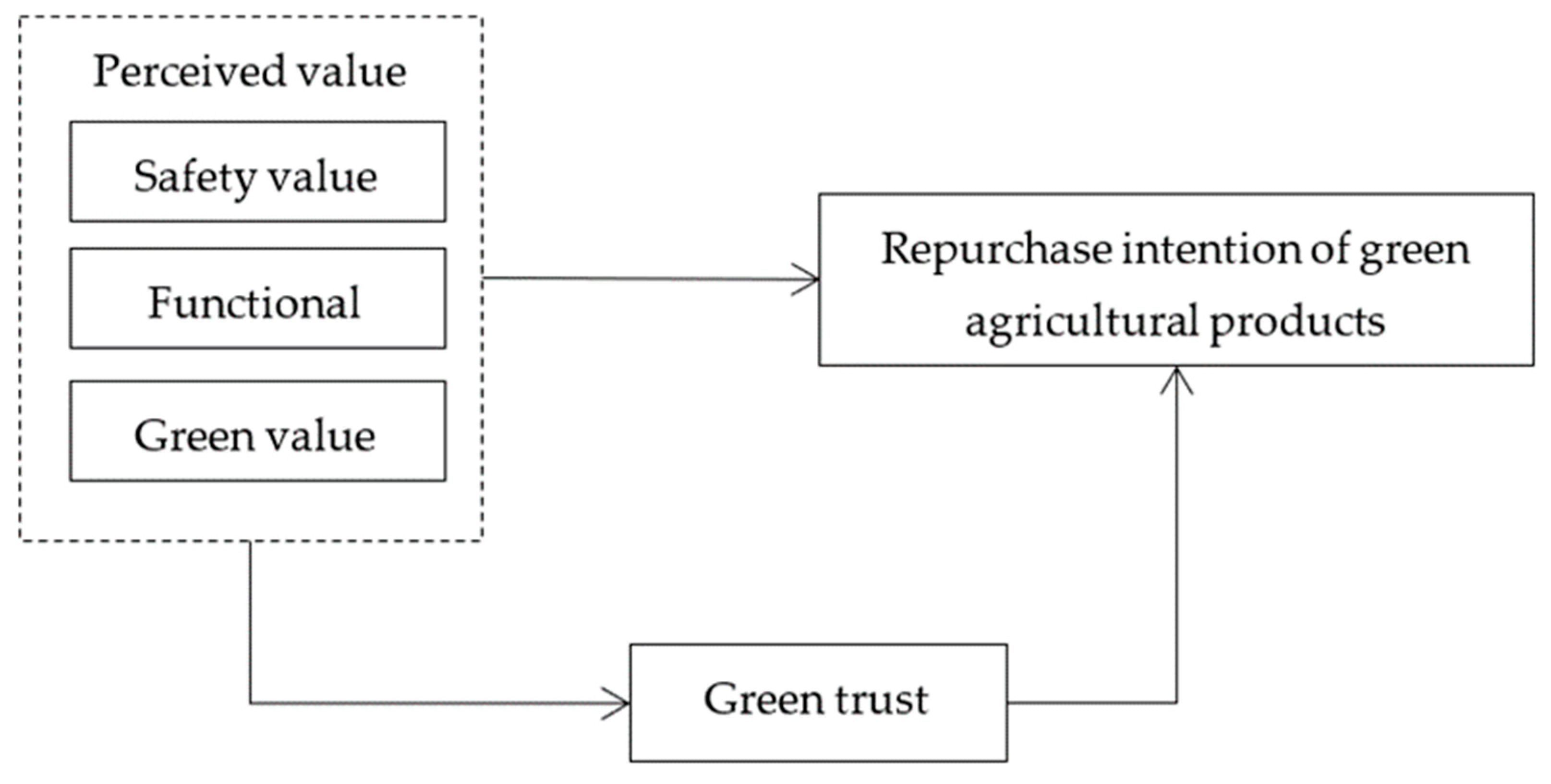

First, the perceived value positively influences consumers’ repurchase intention of green agricultural products. In terms of the degree of influence, functional value is greater than safety value, while green value has no influence (H1a, H1b, and H1c). This finding is similar to previous studies on brand perceived value and repurchase intention. However, there is a difference in that the brand perceived value is divided into terminal product differentiation perception and quality perception, and the influence of quality perception is greater than that of differentiation perception [

74], which is different from the traditional classification. Therefore, it is valuable to study the repurchase intention from different product types and different classifications of perceived value.

Second, green trust plays a mediating role between perceived value and repurchase intention of green agricultural products and plays a fully mediating role on the path from green value to repurchase intention (H2a, H2b, H2c, and H3). This conclusion is different from previous research conclusions on brand perceived value and repurchase intention, that is, brand trust plays a partial mediating role between brand perceived value and repurchase intention [

74]. The reason may be that, for green agricultural products, green value relies more on consumers’ beliefs and expectations about green agricultural products themselves and the producer’s capability, reliability, and goodwill, which in turn generates green trust and further influences the repurchase intention of green agricultural products. In addition, the perceived value significantly and positively influences green trust. In terms of the degree of influence, green value > functional value > safety value. This conclusion is similar to the study by Zhong et al. on perceived value and AI brand quality trust but differs from the conclusion that emotional value has more influence than functional value [

75]. The reason may be that, with the improvement of consumers’ quality of life, consumers mostly concern about the environmental benefits brought by the green agricultural products to society, and the higher the degree of environmental protection, the higher the degree of consumer trust in the greenness of agricultural products. The next concern of consumers is the sense of reliability brought by green agricultural products in terms of quality, variety, and packaging style (trust).

Third, on the one hand, there are significant differences between the types of green agricultural products (necessities and non-essentials) in terms of green value and repurchase intention. Most of the existing research conducts multi-group analyses of purchasing behavior from the perspectives of demographic characteristics and product categories (hedonic and non-hedonic) [

76,

77], and the analyses of necessities and non-essentials are rare. Compared to the green food apple, green food rice has a lower elasticity of demand, and its consumers have a stronger preference for green value attributes, leading to a higher repurchase intention of green food rice than apples. On the other hand, there are differences between the levels of education (low and high education) in the effects of green value on repurchase intention, the functional value on green trust, and green value on green trust. This indicates that consumers with different education levels have different perceptions of green agricultural products and different levels of knowledge about their standards, logos, and certifications [

78].

4.3. Management Implications

Due to the information asymmetry of green agricultural products, it is difficult for consumers to perceive the value of the products during the purchasing process, resulting in a lack of consumer trust in green agricultural products. In addition, the environmental standards, production technical standards, product standards, packaging standards, storage, and transportation standards of its origin are difficult to be identified by consumers and can only be judged from the green label. This black box makes it impossible for consumers to determine the quality of green products, which in turn casts doubt on the authenticity of the label [

88]. Moreover, in the process of interaction between enterprises and consumers, the information on green agricultural products transmitted by enterprises to consumers is insufficient, and it is difficult to display all the information on products with limited labels, resulting in the low perceived value of products by consumers. This information asymmetry makes consumers lack green trust, thereby reducing their desire to purchase [

89]. For this reason, this study puts forward the following suggestions to promote the government and enterprises to formulate relevant measures and marketing strategies, aiming to enhance consumers’ perceived value and green trust in agricultural products.

First, improve the green certification and organic certification mechanism, and strengthen the supervision of green agricultural products by the market. On the one hand, formulate an open and transparent, reasonable and standard, authoritative and detailed certification process, and ensure the unified connection and exchange of certification standards in various regions, which can help the government to regulate green agricultural enterprises for production, packaging, transportation, etc., and provide a strong guarantee for the certification of agricultural products, thus improving consumers’ recognition of green and organic certification and enhancing the perceived value. On the other hand, strengthen the market supervision of green agricultural products certification, crack down the substandard behavior, indiscriminate labeling of certification marks, and exploiting loopholes in the market behavior, and increase the penalties for these behaviors to provide a good market environment for the development of the green and organic market, thereby promoting consumer trust in the certification mark.

Second, strengthen the publicity of green agricultural products and guide the target customer groups to green consumption. On the one hand, relevant government departments can carry out green consumption publicity activities and publicize green agricultural products knowledge to consumers by printing green agricultural product publicity boards, distributing publicity manuals, and designing green agricultural products mini-games, so as to enhance consumers’ functional value, safety value, and green value of green agricultural products, reduce information asymmetry, and promote green consumption. On the other hand, in the selling process of green agricultural products, enterprises can show green agricultural product brochures, promotional videos, and QR codes on the outer packaging of products, and exhibit the standardized, ecological and public process of production, packaging, and transportation of green agricultural products to consumers by scanning the QR codes, in order to enhance consumers’ perception of green agricultural products, improve consumers’ stickiness to green agricultural products, and form attitude loyalty, i.e., consumers’ repurchase intention.

Third, pay attention to quality and safety issues and enhance safety value. On the one hand, the government should lay emphasis on the construction of after-sales complaint channels for consumers, including telephone reporting, online platform reporting, scanning the outer packaging QR code of green agricultural products for reporting, etc. Then, divide the corresponding compensation as well as rewards for whistleblowers according to the severity of the quality and safety problems of agricultural products, so as to enhance consumer trust in the green agricultural products market. On the other hand, the enterprise should trace the whole process of green agricultural products to ensure standardized site selection, safe soil and water source, standardized breeding and seed selection, rationalized fertilization, ecological pest control, environmentally friendly packaging, scientific transportation, and other processes. Moreover, different third-party institutions should be employed regularly to test the products and ensure the quality of green agricultural products from multiple angles and in all aspects, and the full traceability code and the icons of the third-party institutions should be printed on the outer packaging of the products, enhancing the safety value perception of consumers and the credibility of green agricultural products.

Fourth, extend the product industry chain and enhance the functional value. First, deepen the primary industry. Enterprises can optimize breeding selection to screen high-quality ecological germplasm resources and develop different kinds of green agricultural products, including different nutrients as well as different fragrance types, to enhance the space available for consumers to choose from. Second, integrate the primary and secondary industries, strengthen the transformation of green agricultural product processing, and promote the primary processing, finishing, and by-product processing and utilization of agricultural products. For example, rice can be processed into rice flour, rice cakes, rice wine, rice cakes, etc., while apples can be processed into apple juice, apple cider vinegar, canned apples, apple cider, apple sauce, dried apples, etc. This can promote the development of processed products in the direction of easy eating, delicious taste, nutrition, and health care, form product clusters, and then enhance the functional value of green agricultural products. Finally, integrate the primary and tertiary industries, and combine the industrial park of green agricultural products with ecological tourism. For example, paddy field tourism and leisure experience tourism, such as rice cutting competition, unicycle grain transport, scarecrow tying, paddy field painting, etc. can be developed to extend the service industry chain and increase the functional value-added of green agricultural products.

Fifth, consumers should realize that green agricultural products can help improve their own health while reducing environmental pollution. On the one hand, they should enhance their awareness of green agricultural products and actively participate in seminars and lectures held by enterprises and the government to obtain information about green agricultural products, so as to enhance their perceived value and reduce the problems caused by information asymmetry. On the other hand, they should strengthen their own awareness of monitoring the green agricultural products market, and actively report to the government regulatory department when they encounter counterfeit and shoddy green agricultural products, so as to alleviate the crisis of consumers’ trust in enterprises and products. Maintain the orderly and good culture of the green market, enhance consumers’ loyalty and stickiness to enterprises and products, and then generate willingness to buy back.