Abstract

Background: The linkage between teaching and research—also labelled the Teaching Research Nexus (TRN)—is the object of a recurrent debate in higher education. The debate centres on the nature of the interrelation, TRN benefits and challenges, concrete TRN strategies, and its impact on students and academics. Methods: Based on a systematic search of papers published between 2012 and 2022, a systematic review of review studies was conducted, building on articles from the Web of Science and Scopus. Results: From an initial 151 records, 14 fit the review inclusion/exclusion criteria. Goal and review questions: To provide researchers, teachers, and policy decision-makers with an overview of TRN in higher education based on available peer-reviewed review studies, this systematic review was driven by the following guiding questions: What are the conceptual developments in TRN definitions? What are the outcomes of experimental TRN interventions? What are the implementation challenges of TRN in higher education? What TRN implementation strategies have been adopted? Finally, what do the reviews stress as future directions for TRN? Brief conclusion: The review results helped identify patterns in TRN studies, practices, and directions for future TRN research in higher education.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, higher education systems face challenges resulting from their expansion, diversification, massification, and questions concerning their social relevance [,,]. This has had an internal and external impact on the university environment. Externally, universities face accountability questions by constituents and stakeholders; how they deal with the increasing diversification of the student population and the jeopardy in designing and executing their own intellectual agenda []. Internally, these impacts have been observed in the way universities reorganize their structure, redefine their mission, and reconsider the relationship between teaching and research [,,]. Teaching and research are two major functions of higher education institutions (HEI). Therefore, the questions concerning their relationship are not surprising, and are part of a recurrent debate in the higher education literature [].

During the last decade, both non-systematic and systematic review papers have been published focusing on TRN in higher education. The debate has often created controversies, since it involves multiple university stakeholders with diverging interests []. On the other hand, the value of the teaching-research nexus remains unclear []. Non-systematic reviews do provide relevant summaries about TRN practices in higher education, and are a source of ideas, information, context, and arguments both in favour and against. However, they are not comprehensive or controlled in terms of the selection and inclusion of empirical studies. Systematic reviews, in contrast, help address potential bias and can fulfil the role of a scientific gyroscope with an in-built self-righting mechanism []. However, a comprehensive overview of the patterns and results of review studies has not yet been conducted. Thus, the current study offers a review of systematic review studies conducted on TRN in higher education.

2. Trends in TRN Research

Though popular, resilient, and widespread, the relative importance of teaching and research and their relationship have been intensely contested []. While in the English higher education tradition, teaching and research were seen as better carried out in separate institutions, in the German tradition, by contrast, one sees the unity of teaching and research as the core university business. In the American tradition, both roles are regarded as co-existing in varying relations alongside community service and industrial consultancy [,]. The English higher education tradition is anchored in the Ruth Newman idea of a university; the German tradition is closely connected to the Von Humboldt idea of a university; and the America tradition is associated with the Clark Kerr idea of a university. Following these traditions, and incorporating conceptual debates [,], the discussion also expands to the empirical and pedagogical level []. Recently, the discussion has influenced policy reforms and the ranking of university systems in the post-pandemic world [].

At the conceptual level, the debate focuses on the nature and the idea of a university and higher education in general []. These discussions were fuelled by [], who reviewed TRN models based on expected relationships (positive, negative, neutral) and TRN models, within which various moderators and interaction variables are considered.

At the empirical or pedagogical level, both qualitative or quantitative approaches [,,,] have been adopted to analyse TRN and develop evidence about its benefits, challenges, strategies, and future directions. The quantitative studies typically assess linear correlations between the output of teaching and research activities, respective research productivity, and teaching effectiveness. Most quantitative studies conclude that teaching and research (i.e., the output of both activities) are, at most, marginally correlated []. However, there are questions concerning the use of quantitative analysis of the relationship between research and teaching. Alternative approaches build on partial correlations that control the influence of a set of specific variables []. Available qualitative research studies emphasize this TRN complexity and adopt interview tools, focus groups, case studies, and reflective approaches to explore the nexus, academic conceptions of “teaching” and “research” at the level of disciplines and departments, and the impact of institutional, disciplinary, and other contextual factors influencing student experiences of research []. Qualitative studies usually report a strong belief among university stakeholders that teaching and research are positively related. Specifically, most respondents indicate that this positive relationship predominantly works in one way, with the impact of research on teaching being far more important than the other way around [].

In addition to the two abovementioned levels, a more recent debate has focused on the societal impact of higher education, with questions about global expansion, diversification, massification, the social relevance of higher education, the vocational dimension of higher education, and the high-specialisation of research in the post-pandemic world. Within this debate, TRN has been introduced as an idea, a theory, a practice, or a catchphrase, as well as a model, a framework, a policy, or a concept []. These variations—and their related ambiguities—result from the fact that they are often found in policy-making statements, policy documents for HE, mission statements of universities and other institutions of higher education, etc. (see [,]). However, “authors, academics, and policymakers tend to slip between different meanings in an unacknowledged and usually unrecognized way” [] (p.3). Therefore, the way in which the “nexus” is described in case studies and in the literature reflects the multiple linkages and relationships being referred to []. These linkages about the TRN have been primarily perceived as: (a) “functional interdependence” of two academic roles; (b) “conceptual connections” between teaching and research; and finally, as (c) arguments about the roles of graduate and postgraduate students in the context of contemporary “knowledge societies”.

Over time, the reconceptualization of TRN has led to implications for “theory” and “enhancements efforts” in terms of: (i) a deeper appreciation of wider social structural forces in thinking about the nexus; (ii) conceptions of teaching and research—and the linkages between them—as drawing on wider ideological resources which have structural roots; (iii) comprehending ideologically-founded sets of compatibilities and incompatibilities between teaching and research; and (iv) considering differences in the cultures of institutions.

During the last decade, both non-systematic and systematic review papers have been published focusing on TRN in higher education. Review studies are conducted to illustrate the broader picture of a particular topic or focus within a discipline with the purpose of examining the changes and evolution of a discipline to provide scholars with a better understanding of the development of a field and discover any trends [].

However, the growing number of reviews focusing on TRN in higher education again raises new questions, as different conclusions, challenges, and results are continuously being presented. This seems partly related to the nature of the review itself. Based on a review typology [] and approaches to synthesizing research [], three types of reviews can be distinguished: traditional literature reviews, critical reviews, and systematic reviews. Additionally, a review of available TRN review studies is—to our knowledge—currently not available. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to provide researchers, teachers, and policy decision-makers with an overview of TRN in higher education based on available peer-reviewed review studies. Based on the above, we put forward the following guiding research questions:

RQ 1: What are the conceptual approaches and potential changes available in the definitions of the TRN in higher education when looking at TRN reviews?

RQ 2: What are the benefits of an experimental TRN intervention as perceived by academics and students, and as stressed in the review studies?

RQ 3: What are the perceived challenges as to the implementation of the TRN in higher education as stressed in the review studies?

RQ 4: What concrete TRN implementation strategies are discussed in the TRN reviews?

RQ 5: What are the future directions of the TRN in higher education according to TRN reviews?

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

To conduct the systematic review of review studies, we followed the PRISMA guidelines (i.e., preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) and protocol of the PRISMA Group, 2020 []. Review studies published in English between 2012 and 2022 were included in the process, which were available through the Web of Sciences and Scopus.

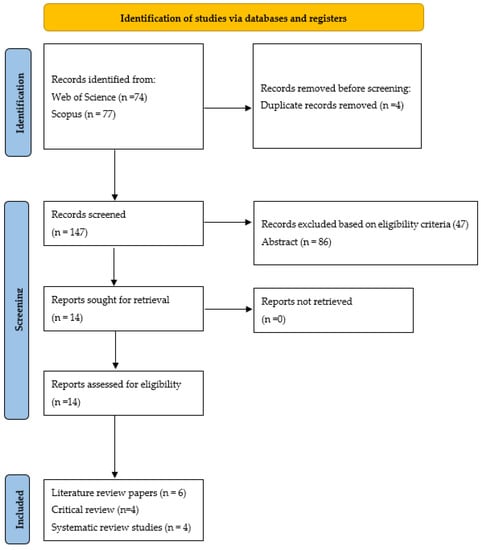

An overview of the related process is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the literature search process.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

The systematic literature review was started by searching relevant publications. Two queries were set up: a first query via the Web of Science database, and a second query via Scopus. The purpose of the main query was to identify relevant peer-reviewed research on the topic. On 1 August 2022, the following combinations of search field tags and search terms were used in the Web of Science: Teaching AND Research AND Nexus AND Review. The additional query was TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Teaching Research Nexus”) AND “Review”. This was repeated using the Scopus database on 4 August 2022. This second query helped identify recent work on the topic, not (yet) included in the Web of Science database. The following time window was consistently applied: 2012–2022.

The search yielded 151 publications, which were all manually screened to verify whether they focused on the topic of the TRN in higher education and whether they were correctly labelled as review papers. A final set of 14 review papers were used as the basis for the review of the reviews.

3.3. Screening and Selection

Relevant publications were exported to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet reporting the title, abstract, keywords, authors’ names, journal name, year of publication, language, and document type. This screening was carried out on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria, as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

An overview of the study of each record is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Type of review, year of publication, and country of origin.

3.4. Data Analysis

In view of the findings obtained in response to the five research questions, the selection of publications was coded through a thematic analysis. Thematic analysis provides a flexible approach that results in a rich and detailed, yet complex account of data []. The thematic coding focused on five main themes central to the research questions: definition, benefits, challenges, strategies, and future directions. A ‘theme’ is considered as a lens by which to capture a perspective, and contributes to developing a level of patterned response or meaning within the dataset []. Although thematic analysis is very often presented as a six-step linear process [,], our data analysis approach was instead characterized as an iterative and reflective process, constantly moving backwards and forwards between phases involving the first and the second author. In addition to thematic analysis, information was also collected regarding reported statistical effects. This is discussed separately in the results section. Analysis of quality was guaranteed by repeatedly reading through the data and re-checking the coding, and decisions were then discussed in the research group until agreement was reached between the first author and the second author.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis and Review Quality Assessment

4.1.1. Review Types and Year of Publication

The set of fourteen review studies—published between 2012 and 2022—reflects methodological diversity. We identified ten non-systematic TRN review studies (traditional narrative reviews (N = 6) or critical reviews (N = 4)), and four systematic review papers. Grouping review types over time, narrative reviews were more dominant in the period between 2012 to 2017 [,,,]. From 2018 till 2022, systematic reviews became the prevailing review type [,,,].

Review studies originated from seven different countries and most reviews were mainly published by authors from the U.K. [,,,,,]. This could reveal stronger support, in a modern context, for the Humboldtian ideal of unifying teaching and research among English academics [].

4.1.2. Teaching and Research Nexus: Review Aims and Questions

Over time, and by observing the aims or questions outlined in the review papers, we observed that only five studies (N = 5) explicitly reported or contained a review aim and review question; seven reported a general aim, and two did not provide review aims. Table 3 provides the details of the review aims and questions.

Table 3.

Review aims and Questions.

As illustrated, the review studies provided a range of aims and research questions appropriate to the topic of TRN in higher education. While some critically discussed the relationship between teaching and research [,,], others centred on providing empirical evidence or arguments to ground the nexus [,,,]. Some review studies advocated novel approaches [], looked into particular effects [], or centred on dysfunctions [] of TRN in higher education. Overall, the review of the review studies helped to develop a very diverse picture of TRN as a field of study that is difficult to allocate to just one perspective or problem field. This seemed dependent on stakeholder perspectives and wider changes in the context of higher education (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic).

4.1.3. Review Methods and Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria

Five reviews contained an explicit statement that the review methodology was defined prior to conducting the review [,,,,], and nine failed to do so [,,,,,,,,].

Only five reviews contained an explicit statement about inclusion/exclusion criteria [,,,,], and, in nine reviews, this item was not applicable due to the review type, i.e., traditional narrative review or critical review [,,,,,,,,].

4.1.4. Review Methodology Limitations and Declaration Statements

Thirteen reviews did not address review methodology limitations [,,,,,,,,,,,,], except one that explicitly mentioned methodology limitations [].

In eight reviews, the authors did not report potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review [,,,,,,,].

4.1.5. TRN: Conceptualization, Benefits, Strategies, Challenges, and Future Directions

All reviews provided conceptualizations regarding TRN, benefits from different stakeholder perspectives, addressed strategies for TRN implementation, challenges, and future TRN directions. In general, the reviews reflected a detailed picture by which to tackle this research question; see summary in Table 4. We discuss this richness in relation to the following research questions.

Table 4.

Quality assessment of the 14 reviews discussed.

4.2. What Are the Conceptual Approaches and Potential Changes in Concepts in the Reviews of TRN in Higher Education?

The Teaching Research Nexus was clearly conceptualized in all review studies. Three levels were distinguished in the conceptualisations:

- (a)

- TRN as part of a long tradition to debate the nature or the idea of a university and/or higher education;

- (b)

- TRN as a description of higher education teaching practices or pedagogy;

- (c)

- TRN as a departing point to critically reflect on the mission of higher education.

These concepts are used to highlight the differences of at least three different traditions of debating the nature or the idea of university, namely, the English, the German, and the American higher education traditions. As previously mentioned, the English higher education tradition is anchored in the John Henry Newman idea of a university, the German tradition is closely connected to the Von Humboldt idea of a university, and the American tradition is associated with the Clark Kerr idea of a university. These traditions reflect the pre-Humboldtian, the Humboldtian, and the post-Humboldtian approaches [,,,,]. In the pre-Humboldtian approach, teaching and research remain institutionally separated, even though links are created between extra-university research bodies and universities. In the Humboldtian approach, the two are funded from the same source and academics adopt both roles, and the organisation is stable. In the post-Humboldtian approach, there is an organisational movement towards differentiation in both roles, and in related funding structures and processes [].

As a description of higher education teaching practices or pedagogy, the concept is used to distinguish modes of enhancing the quality of learning at the university level, during courses, and the classroom experience [,,,,,,].

Further reflecting on the mission of higher education, review studies stress the pressures inflicted on universities due to social, economic, and political changes [,,].

Three review studies conceptualized TRN while reflecting on its historical evolution, and stressed how the face of TRN has changed due to changes in the higher education context or in terms of global developments [,,]. The concept was used to chart the historical transformation of higher education from the legacy of the British ‘colonial college’ to the dominance of the German research university [], or to articulate the gradual swing of the pendulum from one extreme to the other []. The nature of how understandings of TRN have shifted over time form the focus of these review papers by drawing on historical literature to explore these changes.

4.3. What Are the Benefits of an Experimental TRN Intervention as Perceived by Academics and Students?

Data analysis helped to summarise the reported benefits of experimental TRN interventions. While some benefits were related to student processes and variables, others were related to academics. All review papers presented student-related benefits. Some review papers (N = 8) provided benefits related to both students and academics [,,,,,,,]. Student-related benefits were linked to: (i) the development of high-level competencies (such as problem formulation, data analysis, writing, collaboration, and critical thinking); (ii) student cognitions; (iii) research competences; and (iv) personal and discipline-oriented skills. Academic-related benefits were linked to: (i) the teaching process; (ii) pedagogical skills; and (iv) opportunities to refresh knowledge. Table 5 provides a detailed overview of the reported benefits of experimental TRN interventions in higher education.

Table 5.

Benefits of an experimental TRN intervention.

4.4. What Concrete Implementation TRN Strategies Are Discussed by TRN Reviews?

Review studies on the teaching-research nexus offered a large variety of TRN strategies. These placed considerable emphasis on student participation and/or considered how academics use their own pedagogic research to inform teaching.

A range of concepts were used to describe TRN implementation strategies: as a framework [,], a model [,,,,,,,,], a form or approach [,], or as a list of recommendations [,,,] situated within contexts ranging from a discipline, a department, and an institution in a small-scale or large-scale project involving undergraduate and/or postgraduate students. Table 6 presents the details of review strategies of the TRN in higher education.

Table 6.

Strategies of TRN in higher education.

4.5. What Are the Perceived Challenges as to the Implementation of the Teaching and Research Nexus (TRN) in Higher Education?

Considering the variation of implementation strategies, all TRN review studies uncovered many challenges in higher education. These challenges were related to students, academics, institutions, and policies. The same issues were sometimes described as risks [] or barriers [,]. The most comprehensive review reporting a detailed overview of challenges was in []. This review adopted a risk management approach to identify (a) intrinsic, (b) extrinsic, and (c) learning risks.

Most review papers (N = 12) focused on intrinsic risks. This included risks that lay within the actual teaching practices, such as those emanating from curriculum design, lesson planning, delivery in the classroom, and quality of the teaching. Some review papers (N = 5) paid attention to extrinsic risks. These were related to impacts on the teacher from outside the teaching process (institutional policies, government directives, and economic climate). Particular challenges involved the changing nature of academic work and how teachers were influenced by the tension between involvement in teaching and/or research. The latter was often linked to management and funding issues. A smaller number of reviews (N = 5) tackled learning risks or risks identified from the student perspective; for example, when research engagement impacts students’ overall learning experience, or when individual students struggle to cope with additional demands of the research-based learning method. Table 7 provides a detailed overview of the reported TRN challenges in higher education.

Table 7.

Challenges of TRN in higher education.

4.6. What Are the Future Directions of TRN in Higher Education?

Review studies provided interesting future directions for TRN. These did not reflect a return to the so-called ‘golden age of academe’ [], but mainly showed how TRN is influenced by very actual and urgent global challenges, such as environmental destruction, climate change, conflict, and socio-economic inequities [].

Only one review directed attention to the methodology being used []. Some reviews (N = 3) addressed future directions at the conceptual level or frameworks being used [,,]. Others (N = 4) dealt with future practices or pedagogy to implement TRN [,,,]. Most reviews (N = 5) stressed future directions at the institutional and policy level [,,,,]. Table 8 summarizes these in more detail.

Table 8.

Future directions of TRN in higher education.

4.7. Reported Statistical Effects in the Review Studies

As described in the discussion of review results above (see Section 4.3; What are the benefits of an experimental TRN intervention as perceived by academics and students?), all review papers provided evidence about student-related benefits, and some review papers (N = 8) put forward benefits related to both students and academics. The availability of statistical data from these review papers is necessary to explicitly consider results from comparable prior research, thus allowing the aggregation of this statistical body of knowledge at a higher level of analysis, interpretation, and conclusion []. This is critical for a topic where debate often creates controversies and involves multiple university stakeholders with divergent interests []. It also seems crucial in the case of the TRN, since the actual evidence base remains unclear []. This is partly due to the fact that teaching and research are often loosely coupled, while being deeply nested within very different organizational structures []. Therefore, descriptive discussions are hard to generalize across contexts. In contrast, relying on statistical data could make a difference []. It is widely recognized that the proper use of statistics is a key element of research integrity [] and scholars have provided guidelines for experimental [] and quasi-experimental designs [], as well as appropriate statistical procedures to back empirical evidence [,,,,].

Surprisingly, only two review papers reported statistical effects of TRN interventions on students. Indeed, one [] used descriptive statistics to report the percentage of studies reporting the effect of TRN on: (i) students’ improved understanding of subjects and of their relevance to society; (ii) increased collaboration between students when working together to achieve a common goal; (iii) an increase in joint responsibility in carrying out tasks; and (iv) improved interpersonal skills and skills in performing work roles. Furthermore, the second [] reported p-values related to positive effects on: (i) students’ understanding of the natures of research work; (ii) professional practice; (iii) attitude and behaviour for practicing science; (iv) interest in science; (v) career options; and (vi) students’ confidence level while being engaged in research-based courses and undergraduate research programs. Basic descriptive statistics alone are insufficient to carry out a higher-level of statistical analysis. Therefore, a higher level statistical meta-analysis of the review studies could not be carried out.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This systematic review of reviews provides an overview of the TRN in higher education based on literature searches conducted in the August 2022. It reveals that the available review studies allow us to answer key questions concerning the conceptual bases and the evolution in definitions of TRN. The benefits, as perceived by academics and students, types of TRN challenges, and a range of instructional strategies can be used guide its implementation in higher education. Lastly, a structured overview of future directions of TRN could be further developed. However, the review also pointed out a lack of statistical rigour in the reporting of studies. This implied that no meta-analysis could be carried out.

The present review highlighted a methodologically diverse picture in terms of conducting reviews, considering the gradual increase in the adoption of a systematic approach in recent years. The latter meets the growing demand to pursue statistical rigour and move away from non-systematic reviews []. The growing adoption of systematic reviews follows growing trends in review research in other domains; e.g., review studies regarding hospitality and tourism [], social protection [], as well as in gerontology and health services [].

As demonstrated in this paper, available review studies largely differed in their methodological approach because of a focus on multiple university stakeholders with diverging interests [], and often resulted in a very wide overview which was unclear on the value of the TRN [].

The current study helped by comparing and contrasting review studies, and by developing a structured state-of-the-art approach. This study revealed that a conceptual analysis of TRN highlighted variations in traditions of debating the nature or the idea of universities. On the other hand, it can be used as a description of higher education teaching practices or pedagogy to distinguish modes of improving the quality of learning at the university level, during courses, and the classroom experience. Moreover, the TRN is helpful as a starting point to reflect on the mission of higher education in the context of current social, economic, and political changes. Similarly, there has been agreement among scholars regarding the benefits of (experimental) TRN intervention. These are related to student learning outcomes and the development of a wide range of competences that go beyond graduation. Outcomes for academics are related to their teaching and research practices, but also reflect a meso-level impact on curricula and academic culture. When it comes to the question regarding TRN strategies, the review findings placed considerable emphasis on student participation and/or a consideration of how academics use their own pedagogic research to inform teaching. However, all of the TRN higher education review studies also uncovered intrinsic and extrinsic challenges related to students, academics, institutions, and educational policies. Combining research and teaching seems to stretch resources (time, expertise, funding), demands (priorities), and policies (role of university teaching and learning). Future directions for TRN in higher education included incorporating conceptual questions, methodological recommendations, TRN practices, and TRN-related policy developments.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This systematic review has some limitations. First, some available review studies could not be included in our study based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The studies could nevertheless have added to the richness of the data already described above. Precision is required when analysing peer-reviewed research, and analysis of non-English, non-peer reviewed, or excluded studies or reports (such as those found via Google scholar) could help in confirm the present picture of the status of the TRN in higher education or add elements or dimensions not yet identified. Nevertheless, the current analysis could serve as a benchmark for future review studies.

The second limitation is related to the methodological diversity of review studies included in the present systematic review. As reported, between 2012 and 2022, six were classified as traditional narrative reviews, four as critical reviews, and another four as systematic review papers. This might raise the question concerning the level of comprehensiveness or balance in the present analysis. Themes identified through systematic analysis were not ‘quantified’ and could not be studied as to their importance in the TRN debate. In addition, the diversity in TRN research involving very different samples also makes analysis and synthesis difficult. A next-level analysis could be adopted to reanalyse the studies incorporated in the review studies.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the present review helps develop an initial benchmark regarding the status of reviews on the TRN in higher education. It can inform researchers and teachers about the broader nature of TRN, and might inspire other researchers, teachers, and policy-makers to consider the broader picture. This can be achieved against a background of the changing nature of higher education considering the changing demands of society. In the post-COVID period, a stronger emphasis on the societal relevance of higher education can inspire universities to reflect on their own policies and practices, and define how teaching and research are mutually beneficial in supporting the graduation of alumni that fit into the framework of a future-oriented (global) society.

Author Contributions

A.S.U.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing, Editing, Review; M.V.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Review and Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Universidade Eduardo Mondlane (Mozambique) and Ghent University (Belgium) for financial support under VLIR-UOS partnership program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mok, K.H. Higher Education Transformations for Global Competitiveness: Policy Responses, Social Consequences and Impact on the Academic Profession in Asia. High. Educ. Policy 2015, 28, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.H.; Jiang, J. Massification of higher education and challenges for graduate employment and social mobility: East Asian experiences and sociological reflections. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 63, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.H.; Marginson, S. Massification, diversification and internationalisation of higher education in China: Critical reflections of developments in the last two decades. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2021, 84, 102405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyerr, A. Challenges Facing African Universities: Selected Issues. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2014, 47, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, M.; Visser-Wijnveen, G.J.; van der Rijst, R.M.; van Driel, J.H. How to strengthen the connection between research and teaching in Undergraduate University Education. High Educ. Q. 2009, 63, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, W. Integrating Research and Teaching Strategies: Implications for Institutional Management and Leadership in the United Kingdom. High. Educ. Manag. Policy 2005, 16, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburgh, A.; Elen, J.; Lindblom-Ylänne, S. Investigating the myth of the relationship between teaching and research in higher education: A review of empirical research. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2007, 26, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, K.; Rogge, N.; Cherchye, L.; Van Puyenbroeck, T. Economies of scope in research and teaching: A non-parametric investigation. Omega 2013, 41, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, J.; McIntosh, S.; Milligan, L.; Mikołajewska, A. Eyes on the enterprise: Problematising the concept of a teaching-research nexus in UK higher education. High. Educ. 2021, 81, 1023–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1–336. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Shin, J.C. The research-teaching nexus among academics from 15 institutions in Beijing, Mainland China. High Educ. 2015, 70, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, B. The spirit of research. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2021, 47, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tight, M. Examining the research/teaching nexus. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2016, 6, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Beyond the teaching-research nexus: The Scholarship-Teaching-Action-Research (STAR) conceptual framework. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2013, 32, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Donoso, R.; González, C. Undergraduate Research or Research-Based Courses: Which Is Most Beneficial for Science Students? Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordósy, R.; McLean, M. The future of the research and teaching nexus in a post-pandemic world. Educ. Rev. 2022, 74, 378–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J.; Marsh, H.W. The relationship between research and teaching: A meta analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 1996, 66, 507–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, M. Teaching and Research: The Idea of a Nexus. High. Educ. Manag. Policy 2004, 16, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.Q.U. Review of the Academic Evidence on the Relationship between Teaching and Research in Higher Education; Department for Education and Skills: London, UK, 2004; pp. 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jusoh, R.; Abidin, Z.Z. The Teaching-Research Nexus: A Study on the Students’ Awareness, Experiences and Perceptions of Research. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 38, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, J. The Nexus of Teaching and Evidence and Insights from the Literature; Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Trowler, P.; Wareham, T. Re-conceptualising the “teaching-research nexus”. In Higher Education Research and Development; Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australasia: Adelaide, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.S.; Bai, B.H.; Kim, P.B.; Chon, K. Review of reviews: A systematic analysis of review papers in the hospitality and tourism literature. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 70, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, T.; Armarego, J.; Koppi, T. The Teaching--Research--Industry--Learning Nexus in Information and Communications Technology. ACM Trans. Comput. Educ. 2012, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresty, K.A.; Pan, W.; Heffernan, T.; Edwards-Jones, A. Research-informed teaching from a risk perspective. Teach. High. Educ. 2013, 18, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toni, N.; Maphosa, C.; Wadesango, N. Promoting the Interplay between Teaching and Research in the University and the Role of the Academic Developer. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, B.C. Teaching and research in mid-career management education: Function and fusion. Teach. Public Adm. 2016, 34, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, M. Teaching, in Spite of Excellence: Recovering a Practice of Teaching-Led Research. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2018, 37, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, M. A critical evaluation of recent progress in understanding the role of the research-teaching link in higher education. High. Educ. 2014, 67, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, J. From research-as-practice to exploratory practice-as-research in language teaching and beyond. Lang. Teach. 2019, 52, 143–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Vega, L.E.; Suárez-Perdomo, A.; Feliciano-García, L. Inquiry-based learning in the university context: A systematic review. Rev. Esp. Pedagog. 2020, 78, 519–537. [Google Scholar]

- Børte, K.; Nesje, K.; Lillejord, S. Barriers to student active learning in higher education. Teach. High. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, C.; van de Schoot, R. Bayesian statistics in educational research: A look at the current state of affairs. Educ. Rev. 2018, 70, 486–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaree, D.F. The lure of statistics for educational researchers. Educ. Theory 2011, 61, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Steiner, P. Quasi-Experimental Designs for Causal Inference. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 51, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zendler, A.; Vogel, M.; Spannagel, C. Useful experimental designs and rank order statistics in educational research. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 2012, 2, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Resnik, D.B. Statistics, ethics, and research: An agenda for education and reform. Account. Res. 2000, 8, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, B.G.; Shafer, K.; Miles, A. Inferential statistics and the use of administrative data in US educational research. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2017, 40, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.; Byrne, J. The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, C.; Bakrania, S.; Ipince, A.; Nesbitt-Ahmed, Z.; Obasola, O.; Richardson, D.; Van de Scheur, J.; Yu, R. Impact of social protection on gender equality in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of reviews. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Dutt, A.S.; Nair, R. Systematic review of reviews on Activities of Daily Living measures for children with developmental disabilities. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).