Abstract

Enhancing faculty performance and student interaction during the lecture is essential to achieve sustainable learning development. The current study aims to evaluate the effect of using “Student response systems (SRS)” on faculty performance and student interaction in the classroom. The faculty members at King Saud University were encouraged to join a university-scale educational project that involve utilizing SRSs within their classes. From Fall 2016 to Fall 2019, a total of 371 faculty members and 19,746 students were enrolled in the current study. By the end of each semester, faculty and student satisfaction surveys were distributed to evaluate their perceptions of using SRS in the class. The faculty members’ and students’ response rates were 75.7% and 38.1%, respectively, and represented 18 different colleges from different disciplines within the university. Furthermore, the study covered a wide range of study levels for bachelor’s degrees ranging from levels 1–10. The study demographics showed that 60% of the total participating faculty members and 64% of students were females. Interestingly, the majority of participating faculty members (40%) and students (44%) belong to health colleges. Among the most beneficial effects of using SRSs, is that it increased the interaction, focus, and participation of students in the lecture and stimulated their desire to attend and prepare for the lecture. It also helped the faculty members to improve their teaching strategies and enabled them to know the weaknesses or strengths of students, which in turn led to the improvement of the entire educational process. The majority of faculty members as well as the students recommend applying it in other courses and future semesters. These findings were generally consistent over the whole studied seven semesters. SRSs offer a potential tool to improve faculty teaching practices, enhance student engagement, and achieve sustainable learning development among different disciplines.

1. Introduction

Student–faculty interaction is a prerequisite for ensuring the success of any educational environment and achieving its objectives in acquiring the required information and skills [1]. However, many difficulties prevent students from acquiring skills and information in the classroom, including, for example, the large numbers of students in the class, and the personal aspects of the student such as shyness, hesitation, and lack of self-esteem, which in turn reduces students’ interaction and participation in the classroom [2]. On the other hand, the faculty member faces difficulties in explaining information to students, these include their lack of knowledge of the student’s previous experiences and backgrounds. As well as the difficulties that a faculty member may face in the class in determining the level and progress of each student individually [3], he may attempt to distribute worksheets to all students, evaluating them and seeing their progress, one student after another, and this requires a great time and effort from the faculty member, which would be better invested in more useful tasks and activities for students.

Many studies indicate that there are some students who tend to be passive in learning, and this appears through their reluctance to answer the lecturer’s questions. It may be one of the reasons that these students do not want to appear and express themselves in front of their colleagues. Some of them do not want to draw attention and/or fear the embarrassment of answering questions incorrectly. These learning styles make the assessment method difficult for the lecturers and can impose a negative influence on the effectiveness of learning and teaching [4].

With the advancement of technology and its availability, it has become necessary to use it to solve problems related to education, particularly the introduction of an interactive classroom in which the student is the main focus and is given the time and opportunity to participate and interact with the scientific material presented. The continuous development of modern teaching methods, by teachers, is vital to enhance learning, including the involvement of students in the educational process and the use of modern and more effective teaching techniques during lectures [5,6].

In addition, it is important to provide the technical means available to the faculty member to assess students and determine their comprehension levels in the class.

Student response systems, namely “SRSs”, are interactive remote answering devices that allow lecturers to gain prompt feedback from their students in class [7]. This helps improve class participation and the implementation of active and cooperative learning. SRS has gained increasing popularity among educators. SRSs are simple, prompt feedback and introduce the anonymity feature that can help students to express themselves more freely in class. The improved response rate and immediacy of response enabled by SRS can help lecturers effectively assess the student’s learning progress in class [8]. Furthermore, the SRS system is convenient to use in classrooms that are constantly growing in student numbers [9]. When integrated into traditional lectures, such interactive systems can help to promote active/collaborative learning, increase student engagement, encourage class participation, and eventually improve student learning outcomes [4,7]. It also increases class attendance [10] and learning motivation [11].

However, empirical evidence on the impact of SRS on student performance in the assessment is inconsistent [12]. Stanley showed that the use of SRS leads to improved performance of students in terms of attendance as well as unannounced class quizzes [13]. On the other hand, some studies indicated that the effect of SRS was not significantly positive on student performance. Liu et al. suggested that the use of SRS has a modest, statistically insignificant impact on student performance [14]. It has a modest and statistically insignificant effect on students’ performance [14].

Hayter and Rochelle reported that, although the survey results confirmed that most students enjoyed using the SRS, their overall performance as measured by the quiz and final exam scores did not increase significantly [15].

Researchers have also investigated the effect of SRS with consideration of the attributes of the students and the characteristics of the subjects [16]. Green (2016) compared student exam performances among classes with and without SRS, with a specific focus on student background as measured by the Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT) score. It was found that the implementation of SRS led to a significant positive increase in student performance, but the degree of improvement depended on students’ SAT scores [17]. In particular, students with higher SAT scores benefitted more from the use of SRS.

Accordingly, there is an indigence to develop learning activities that are interactive and user-friendly, foster student engagement in the learning process, and avoid technical issues. Hence the idea of the Personal Response Systems (SRS) project, which aims to integrate technology into education to create an interactive classroom between a faculty member and his students to save time and effort and enhance the learning process and make it more enjoyable and stimulating. Accordingly, in 2013, the Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching at King Saud University (KSU-CELT) announced the launch of the student response systems “SRS” program to introduce an active learning tool for university students enabling them to actively participate in class with a high level of interaction and enhanced learning outcomes.

The main goal of this study was to obtain a quantitative assessment of the SRS by students and teachers in terms of effectiveness, perception, and acceptability [18]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind that evaluates the use of SRSs on such a large students number with diverse disciplines and study levels. Important questions that can be addressed by the current study include: “Does the use of SRS enhance the active learning practices of faculty members?” and “Does the use of SRS enhance students’ interaction and achievement within and outside the lecture?” [18]. Accordingly, Faculty and students’ perceptions/preferences were analyzed to evaluate the learning tool from diverse aspects.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a comprehensive cross-sectional study that utilized a descriptive research design [7]. The study was conducted in 18 colleges within King Saud University which involves the various disciplines of health, science, community, humanities colleges, and preparatory year (Level 1–10, Bachelor’s degree, male and female campuses).

2.2. Procedure

The “SRSs” educational project for faculty members and students was launched and organized by CELT-KSU which was responsible for project funding, execution, SRS devices acquisition, technical support, and data collection. At the beginning of each semester (Fall 2016–Fall 2019), the CELT-KSU announced an invitation for voluntary participation in the Personal Response systems “SRSs” educational project. The program targeted the faculty members at King Saud University in all colleges/disciplines. Faculty members, who were interested in using SRS in their live courses, had to consent to the following conditions:

- The participating faculty member must efficiently utilize the SRS in the learning process at least in six lectures (at least three questions each) within the semester.

- The participating faculty member must fulfill the final report on using SRS within the semis miter.

- The participating faculty member should use the SRS with bachelor’s sections where at least one section includes a minimum of 15 students.

- The participating faculty member should submit the faculty survey and encourage his/her students to fulfill the students’ survey on utilizing SRS.

- The newly engaged faculty members shall receive financial support for their efforts in using, managing, distributing the SRS devices, collecting data, and sending the reports on the project (irrespective of their students’ or their own opinion of using SRS).

The participating faculty members were encouraged to use the SRS system in several class tasks such as taking attendance, in-class polling, pre-class, and post-class quizzes, and other techniques that can enhance student interaction during the lecture.

2.3. Questionnaires to Evaluate Student’s and Faculty’s Perceptions

At the end of each semester, all participating KSU faculty members were encouraged to participate in a voluntary survey to solicit their feedback about using SRS [18]. The surveys were designed in Arabic and English languages. The surveys mainly involved the following sections: general information, faculty perceptions of SRS technical problems, the effect of using SRS on student achievement, improving faculty member teaching strategies, and students’ interaction during the class (from the point of view of a faculty member), and faculty members’ attitude toward the use of SRS and/or comments/suggestions (if any).

The general information section collected the gender, discipline, academic rank, and name of the faculty member, which was then anonymously coded and secured to maintain the privacy of the participants all over the subsequent data analysis and presentation. In addition, each of the data collection, anonymization, and data analysis processes was conducted by a separate researcher. The collection of faculty identity was necessary to determine how frequently each faculty member was interested in continuously utilizing the SRS in the subsequent semesters (up to seven semesters). On the other hand, each faculty member, who participated in the CELT-led SRS project, consented to submit this survey by the end of the semester. In fact, the collection of faculty names was also necessary to follow up on the effectiveness of SRS utilization by each participating faculty member in the CELT-led SRS project.

Another anonymous, voluntary survey was designed to solicit students’ feedback about using SRS. The survey was in the Arabic language and was designed to evaluate student feedback anonymously. The surveys mainly involved the following sections: general information, student’s perceptions of SRS technical problems, the effect of using SRS on student interaction during the lecture, student achievement, student attitude toward the use of SRS, and/or student evaluation of the faculty member performance using the SRSs.

All surveys were created using Google Forms® and the survey links were sent by email to the faculty member so that he/she completes the faculty survey and forward the students survey to his students encouraging them to complete it [5].

2.4. Validity and Reliability of the Surveys

The research tool was designed to measure the satisfaction of the participating faculty members and students with the use of SRS in education. The tool was designed based on global studies and experiences, which were reviewed and improved during the study phases. Each questionnaire was reviewed linguistically and analytically to confirm that the presentation of questionnaire items was relevant to the study aim and unambiguous to understand or answer [19]. The questionnaire Likert scale items were mainly rated from 1 (strongly disagree, invalid, never, etc.) to 5 (strongly agree, highly valid, Always). The scale items were subsequently assessed by descriptive analysis namely, the mean and standard deviations [20]. The reliability of the two questionnaires was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha (α) value. The alpha value > 0.7 was considered acceptable for scales with more than 10 items [21,22,23]. However, for a scale with less than 10 items, an Alpha value > 0.5 is considered acceptable [24].

2.5. Factor Analysis of the Surveys

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to identify the factors (dimensions) underlying the variables of faculty and student questionnaires. In particular, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin and Bartlett’s tests of Sphericity were used to assess the factorability of the data. Scree test was applied to determine the number of factors (dimensions) to be extracted. Principal Component Analysis with VARIMAX rotation was applied to minimize the number of variables that have high loadings on each factor [25].

2.6. Characteristics of the Participants

A total of 371 faculty members and 19,746 students were enrolled in the current study starting from the Fall 2016 semester to the Fall 2019 semester. The total faculty members and students’ responses reached 279 and 7526 representing 75.2% and 38.1%, respectively, after excluding identifiable duplicates in the same semester. Among the faculty members, nine respondents refused to represent/share their responses and hence their responses were excluded from the study.

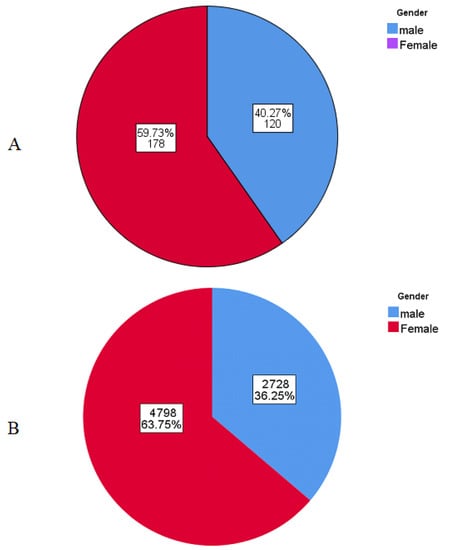

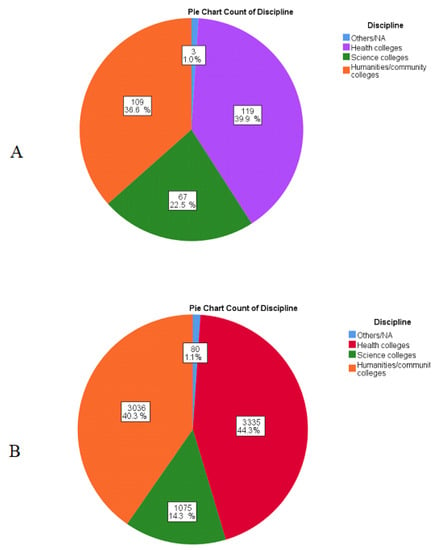

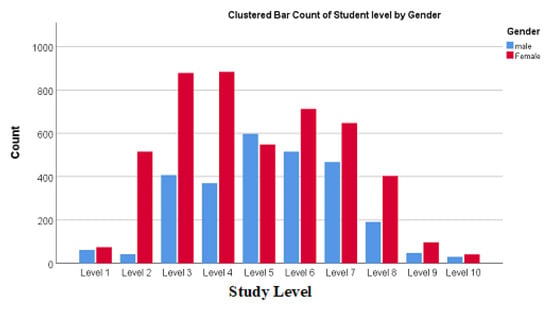

The study covered seven consecutive semesters from Fall 2016 to Fall 2019. The study demographics showed that 60% of the total participating faculty members and 64% of students were females (Figure 1). The study showed a relative increment in the number of participating faculty and students starting from the Spring 2018 semester (Figure 2). There was a minor drop in the semester of Fall 2019, which might correspond to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study involved wide distribution among different disciplines covering up to 18 colleges within the university. Interestingly, the majority of participating faculty members (40%) and students (44%) belong to health colleges (Figure 3). In addition, the majority of participating faculty members (45%) were assistant professors (Figure 4). Interestingly, the study covered wide study levels of bachelor degrees ranging from levels 1–10 with a peak of participants at levels 3 and 4 (Figure 5). The Students’ GPA ranged from 1 to 5 with an average of 4.1 ± 0.6 (n = 3304).

Figure 1.

The distribution of (A) faculty and (B) students’ responses based on gender.

Figure 2.

The distribution of (A) faculty and (B) students’ responses all over the semesters from Fall-2016–Fall-2019.

Figure 3.

The graphical distribution of (A) faculty and (B) student responses based on scientific disciplines.

Figure 4.

Graphical distribution of faculty respondents based on the scientific degree.

Figure 5.

Bar count cluster of participating students based on the study level.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

Retrospective analyses of students and faculty feedback were collected as part of a normal quality assessment of the university’s educational practices. The faculty survey collected the faculty member’s name, which was then anonymously coded and secured to maintain the privacy of the participants all over the subsequent data analysis and presentation. In addition, each of the data collection, anonymization, and data analysis processes was conducted by a separate researcher. The collection of faculty identity was necessary to determine how frequently each faculty member was interested in continuously utilizing the SRS in the subsequent semesters (up to 7 semesters). On the other hand, the participating faculty members consented to submitting this survey by the end of the semester. The students’ survey was anonymous and voluntary. All the information collected from the participating faculty and students was managed confidentially.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The overall satisfaction score (OSS) of SRS use was calculated based on the average score of each respondent in all Likert scale items (faculty FQ1–FQ16 and students SQ1–SQ23). The OSS ranged from 1 (highly unsatisfied) to 5 (highly satisfied). The statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 (IBM, Armonk, New York, NY, USA). The ANOVA followed by LSD and independent t-test were used to assess the effect of the study variables such as gender, discipline, and academic rank on overall faculty and student satisfaction (OSS) with SRS use. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Regarding the faculty survey, the value of KMO statistics was found to be 0.826 (>0.6) and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was highly significant at p < 0.001 (Table 1). Regarding the student survey, the initial screening of the questions SQ1–SQ29 (by KMO and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity) revealed that statistical analysis could not be computed probably because correlation coefficients could not be computed for all pairs of variables. Upon excluding SQ24–SQ29 and repeating the test for SQ1–SQ23, the KMO value was found to be 0.955 > 0.6, and Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was found to be highly significant at p < 0.001 (Table 1). The high KMO value shows that sampling is adequate and the factor analysis is appropriate for the data. Bartlett’s test of Sphericity is highly significant at p < 0.001, which shows that the correlation matrix has significant correlations among at least some of the variables. Hence, the hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix is rejected. Therefore, factor analysis may be worthwhile for the data set [25].

Table 1.

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity.

The principle component analysis (PCA, conducted by the Scree test) with VARIMAX rotation suggested a minimum of five components (underlying dimensions), with the eigenvalue > 1, for the faculty survey (FQ1–FQ16) and four components (underlying dimensions), with the eigenvalue > 1, for the student survey (SQ1–SQ23) (Figure 6A,B). According to these findings and the suggested study dimensions, the faculty and student questionnaire items were categorized into dimensions (F-D1: F-D5) and (S-D1: S-D6), respectively (Table 2). The PCA was re-conducted for each suggested dimension and confirmed items’ high loading within their suggested dimension.

Figure 6.

Scree plots of (A) faculty questionnaire items (FQ1–FQ16), (B) Student questionnaire items (SQ1-AQ23), and (C) Student questionnaire items (SQ25–SQ29).

Table 2.

The internal consistency of faculty and students survey results.

For SQ24–SQ29, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity significance was less than 0.0001 and KMO was 0.690 (>0.6), which indicates that factor analysis is appropriate for the data. The PCA with VARIMAX rotation suggested that SQ28 and SQ29 did not fit in the same underlying dimension as SQ25–SQ27 (Figure 6C, 2 dimensions with the eigenvalue > 1). However, these five items aimed to measure the extent of faculty use of SRS to accomplish different tasks within the class. Accordingly, SQ25–SQ29 hence were grouped in the same dimension.

The Cronbach’s alpha (α) values for faculty survey dimensions (F-D1: FD-5) ranged from 0.673 to 0.789 and the alpha (α) values for student survey dimensions (S-D1: S-D6) ranged from 0.671 to 0.916 (Table 2). These data indicate good internal consistency and high item correlations for both faculty and student surveys [18,25].

The statistical analysis of Faculty characteristics revealed that scientific discipline and academic rank showed significant effects on OSS (Table 3). In particular, faculty in science colleges showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher OSS compared to their colleagues in humanities/community colleges. In addition, professors and associate professors showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher OSS compared to other academic ranks. On the other hand, the statistical analysis of students’ characteristics revealed that the semester, scientific discipline, and gender showed significant effects on OSS (Table 3). In particular, earlier semesters (Fall 2016 to Spring 2017) showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher OSS compared to each of the subsequent semesters (Fall 2018–Fall 2019). Students in humanities/community colleges showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher OSS compared to their colleagues in science and health colleges. Interestingly, female students showed significantly (p < 0.05) higher OSS compared to male students.

Table 3.

Statistical analysis of the effect of Faculty and students characteristics on the overall satisfaction score (OSS).

Regarding the technical use of SRS, an average of 92% of faculty members and 95% of students agreed/strongly agreed with the ease, clarity, and lack of technical problems using SRSs within the class (Table 4 and Table 5). Regarding the effect of SRSs use on student interaction during the lecture, an average of 97% of faculty members agreed/strongly agreed that the use of SRSs enhanced student focus, and participation during the lecture and encouraged them to answer questions with no hesitation or fear (Table 6). Similarly, an average of 87% of the students agreed/strongly agreed that the use of SRSs enhanced their focus, and interaction during the lecture, encouraged them to answer the questions and helped them to assess themselves efficiently (Table 7). Regarding the effect of SRS use on students’ achievements, 64% and 72% of the faculty members agreed/strongly agreed that SRS use increased students’ attendance and intention to prepare for class, respectively (Table 8). Similarly, 76% and 66% of the students agreed/strongly agreed that SRS use made them more eager to attend the lecture and prepare for them, respectively (Table 9). In addition, 86%, 74%, and 68% of the students agreed/strongly agreed that SRS use improved their understanding of the scientific material, their academic achievement in the course, and their enthusiasm for studying, respectively (Table 9).

Table 4.

Faculty perception on the technical use of SRSs (Dimension F-D1).

Table 5.

Students’ perception of the technical use of SRSs (Dimension S-D1).

Table 6.

Faculty perception of the effect of SRS use on students’ interaction during the lecture (Dimension F-D2).

Table 7.

Students’ perception of the effect of the SRS use on students’ interaction during the lecture (Dimension S-D2).

Table 8.

Faculty perception of the effect of SRS use on students’ achievements and interaction outside the class (Dimension F-D3).

Table 9.

Students’ perception of the effect of SRS use on students’ achievement outside the class (Dimension S-D3).

Regarding the effect of SRSs use on improving faculty teaching strategies, 94% and 98% of the faculty members agreed/strongly agreed that SRS use helped them to find out the weak points and the actual comprehension level of students during the lecture, respectively (Table 10). In addition, 95% of the faculty members agreed/disagreed that SRS use enhanced their teaching strategy. Similarly, 96% of the students agreed/disagreed that the faculty member’s performance using SRS was appropriate and that he/she discussed the student’s answer to questions (Table 11). The students’ responses regarding faculty use of the SRS clarify that the majority of the faculty members were using SRSs in assessing students’ understanding during and at the end of the lecture while they were less commonly using it in assessing students’ pre-lecture knowledge and even far less using it in exams or monitoring the attendance (Table 12).

Table 10.

Faculty perception of the effect of SRS use on identifying students’ level of understanding and weak points (Dimension F-D4).

Table 11.

Students’ perception of faculty performance using SRS (Dimension S-D4).

Table 12.

Students’ perception of the tasks accomplished by SRS (Dimension S-D5).

Regarding their attitude toward the use of SRS, 97% and 99% of the faculty members agreed/strongly agreed that using SRS made the lecture interesting and that its advantages exceeded its disadvantages, respectively (Table 13). In addition, 97% of the faculty members expressed their wish to use it in future courses and recommended spreading its use among different colleges and departments (Table 13).

Table 13.

Faculty attitude toward the use of SRS (Dimension F-D5).

Similarly, 93% and 91% of the students agreed/strongly agreed that using SRS made the lecture interesting and that its advantages exceeded its disadvantages, respectively (Table 14). In addition, 84%, and 90% of the students expressed their wish to use it in the rest of the current courses and future courses, respectively. In addition, 90% recommended spreading its use among different colleges and departments. Interestingly, 79% of students preferred the courses that utilize SRSs over the others. Approximately 48% and 25% of the students sometimes or always talk to their classmates in other classes about their use of SRS, respectively (Table 14).

Table 14.

Students’ attitudes toward the use of SRS (Dimension S-D6).

A follow-up data analysis was conducted to evaluate the tendency of faculty members to continue using SRS in subsequent semesters. All over the seven studied semesters, the frequency of faculty use of SRSs ranged from 1 to 6 times with an average of 2.10 for male faculty members and from 1 to 7 times with an average of 1.86 for females (p = 0.349) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Frequency of faculty usage of SRS per 7 semesters based on gender.

4. Discussion

This study is the first attempt in the literature that examines the effectiveness of SRS in a huge student/faculty population with diverse disciplines and general attributes like gender, college, student GPA, Student study level, and faculty academic rank. In the current study, the use of SRSs was investigated for its potential enhancement of the teaching performance of faculty members. In addition, it also evaluated the potential effect of SRSs use on student engagement within and outside the class.

The faculty members’ and students’ response rates were 75.2% and 38.1%, respectively. This difference in the response rate, where it was greater for teachers compared to students, could be explained by one or more of the following reasons, (1) seriousness and a sense of responsibility and importance is usually greater among teachers, (2) ease of communication and sending reminders to teachers is greater compared to students where communication was not direct but through teachers, and (3) distraction, inaction and lack of motivating factors among students. This was also consistent with what Ahmad reported emphasizing the low rate of student participation in online questionnaires, citing many references [26].

The use of SRS showed a positive influence on both faculty members and students. Both faculty and students expressed a high OSS (4.5 and 4.3, respectively). The higher OSS of professors and associate professors indicates the good perception of senior teachers of SRS use. On the other hand, the reduced student satisfaction (OSS) in late semesters compared to earlier ones reflects the need for continuous improvement of teaching technologies and activities to satisfy the rapidly growing demands and expectations of the new generations. The higher satisfaction (OSS) of female students compared to male ones is in agreement with their orthogonal personality traits of being more shy as compared to males [27]. In this context, Li reported that SRS is more advantageous to students who prefer indirect means of communication [3].

The results also indicate a high percentage of faculty members’ positive attitudes toward using devices throughout the project stages. In addition to the convergence of most of the participants’ answers to confirm that the statements are true to a large to a moderate degree. The data provided by the participants from the faculty members indicated the high rate of dialogue and positive discussions in the classroom and the promotion of learning, which potentially affects academic achievement. In addition, some faculty members added that the use of SRS succeeded in attracting the attention of students during the lecture, which reduced their use of their mobile phones and reduced marginal conversations between students. The participating faculty members also acknowledged the advantage of using the SRS in saving time and effort.

Similarly, the students’ survey results indicate that the trend toward the effectiveness of the SRSs was positive among the participating students, with high rates. The overall results showed a high level of student satisfaction with the positive change achieved by the SRS, particularly for performance in lectures, as the use of the device effectively contributed to making positive changes such as encouraging them to focus, think, and analyze more in the lecture, and increase their chances of participating effectively and answering without hesitation or fear. The students’ responses reflect their satisfaction with the use of SRS in the classrooms, which is one of the indicators of the success of the SRS project.

Most of the faculty and students perceived that the SRS was user-friendly, technically simple, and engaged the students within the lecture. Most importantly, the majority of faculty and student comments indicated that the SRS was successful in helping students to focus during the lecture periods. Several previous studies showed positive educational outcomes of “SRS” [16]. Middleditch and Moindrot showed that the use of SRS can increase student satisfaction, make them enjoy learning, and encourage participation. [28]. Other studies showed that the use of clickers increased student enthusiasm, and this was demonstrated by increased levels of answering multiple-choice questions, as well as increasing student attendance and positive exit survey opinions. [29,30].

On the other hand, most faculty and students agreed that the SRS was useful in encouraging them to answer, discuss, and interact with the instructor comfortably. These results are in agreement with previous studies which showed that the students preferred SRS due to its anonymity [8]. Li reported a study that utilized “SRS” in teaching an intermediate-level economics course. The students’ questionnaire results show that around 75% of students in the treatment (SRS) group generally agreed that SRS allowed them to express their views more freely [3].

In addition, most faculty and students agreed that the SRS was useful in displaying students’ comprehension level of the scientific material during class and helped to find the weak points of the students and their misunderstandings. Similar findings were reported in previous studies. Following these findings, Bordes et al. utilized the SRS to assess students’ in-class knowledge by using in-class polling to gauge students’ understanding of the key lecture concepts [31]. He concluded that the SRS served as a potential teaching tool to identify student misconceptions and improve student learning outcomes [31]. Li reported that the use of SRS also benefits the lecturer as the teaching evaluation of the lecturer was significantly better for the SRS group [3,4]. Bares López et al. (2017) reported that students generally considered SRS a useful tool for detecting gaps in the understanding of course content gaps [16].

Interestingly, most faculty and students agreed that the SRS enhanced students’ attendance and enthusiasm to prepare for the lecture. In addition, most students perceived that SRS enhanced their academic achievement in the course and increased their enthusiasm for studying. These results also indicated that the use of the SRS had another positive effect on students’ achievement outside the lecture hall.

Regarding their attitude toward SRS use, the results were encouraging and positive, as most of the faculty and students supported the generalization of the experience for its benefit, and they also expressed their desire to continue using the SRS in the coming classrooms. These findings were correlating with the results of the frequency of faculty member use of SRS during the study period. On average, the faculty members continued to use the SRS for a second semester within the study period, which reflects their satisfaction with their initial experience using SRS. In addition, the increased percentage of faculty members and students that utilized SRS during the later semesters indicates the acceptance of such devices in their regular teaching/learning practices.

As presented in this paper, the positive impacts of the use of SRS in King Saud University echo many of the impacts documented in the literature focused on North America and Europe, but these positive impacts do not come in isolation. The findings of this study provide further evidence of the effectiveness of SRS, particularly in the Saudi context [3].

However, implementing the SRS project at KSU faced several challenges and problems. In the early stage, it was essential to follow up on the faculty member’s ability and enthusiasm to commit to using SRS according to the correct method. Therefore, the executive committee in CELT assigned a technical member in each college to continuously monitor and motivate the teaching staff, which had a positive impact in this context. There was another issue regarding the way of student acquisition of the SRS devices, whether to distribute the devices to them once at the beginning of the semester or take the devices from students and bring them to each lecture. Both options were adopted by different colleges and each option had its advantages and disadvantages. The Executive Committee at this stage also discussed other options such as the possibility of using smartphones instead of the SRS, but this was not appropriate for technical and scientific reasons. As smartphones will be a source of distraction for students and not focus during the lecture. It also requires constant internet access throughout the lecture time, which is not available in some college halls, which hinders the success of the project. In addition, it can create negative discrimination against students who do not have smartphones. Another option was also discussed, which is using the learning management system (Blackboard) as an alternative to SRS. However, global experience and practices confirm the difference in the goal between them, as the SRS specializes in activating teaching and raising the level of its quality during the lecture and in the classroom. A comparison was also made between the blackboard and the clickers system on some courses, and the difference was significant in favor of the SRS on improving teaching inside the classroom. However, it is possible to merge the data used in SRS into BlackBoard, but Blackboard cannot be a substitute for SRS. Accordingly, the merge between SRS and Blackboard was adopted, at a later stage of the project, to facilitate the transfer of students’ grades.

There are several potential areas for future study such as assessing the impact of SRS on student knowledge retention. Although the students benefitted from the SRS use individually, incentives such as requiring students to work in teams when submitting their questions could have further positive learning outcomes arising from the team-based learning activities [5,32]. More robust studies are needed to shed light on student-led activities using SRS.

Although the current study collected feedback from a diverse and huge number of students in terms of their perception of SRS use on their performance and achievement, further studies should emphasize evaluating SRS impact on their performance in pre-, post-lecture quizzes and final exams. In addition, the SRSs were mostly used in close-ended questions such as multiple choice and true/false. It may be helpful to search for new ideas to use SRS in other questions that evaluate critical thinking skills such as short-answer questions.

5. Conclusions

Through this study, which covered 18 colleges of King Saud University, the majority of participating faculty members and students were females and belonged to health colleges. Of the most important study findings, SRS increased the interaction, focus, and participation of students during the lecture, as well as increased student attendance, preparation, and readiness for lectures in the classroom. The use of SRSs in the classroom also enhanced students’ understanding of the material and raised their scientific achievement and enthusiasm for study. As for faculty members, it helped to improve their teaching strategies and enabled them to know the strengths or weaknesses of students, and this, in turn, led to the improvement of the entire educational process. The majority of the participating faculty members concluded that using SRSs increased the enjoyment of the lecture and expressed their desire to use it in future classes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.; validation, A.A.-W.S. and W.S.; formal analysis, A.A.-W.S.; investigation, O.A. and E.A.; resources, S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-W.S. and W.S.; writing—review and editing, A.A.-W.S. and W.S.; visualization, A.A.-W.S.; supervision, S.A.; project administration, O.A. and E.A.; funding acquisition, O.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia - project number IFKSURG-2-342.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number IFKSURG-2-342.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Komarraju, M.; Musulkin, S.; Bhattacharya, G. Role of Student–Faculty Interactions in Developing College Students’ Academic Self-Concept, Motivation, and Achievement. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2010, 51, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, J.M.; Kennedy, G.; Lockyer, L.; Arguel, A.; Pachman, M. Understanding Difficulties and Resulting Confusion in Learning: An Integrative Review. Front. Educ. 2018, 3, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. Communication preference and the effectiveness of clickers in an Asian university economics course. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, S.; Heilmann, S.G.; Hubbard, A.R. Student perceptions regarding clickers: The efficacy of clicker technologies. In End-User Considerations in Educational Technology Design; IGI Global: Hershey, Pennsylvania, 2018; pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Shahba, A.A.; Sales, I. Design Your Exam (DYE): A novel active learning technique to increase pharmacy student engagement in the learning process. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 1323–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shammari, T.H.; Al Massaad, A.Z. The effect of using flipped classroom strategy on academic achievement and motivation towards learning informatics for 11th grade students. J. Educ. Psychol. Stud. 2019, 13, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebelego, I.-K. The use of clickers to evaluate radiographer’s knowledge of shoulder images. Health SA 2019, 24, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, F.; Braun, I.; Körndle, H.; Schill, A. Metacognitive support in university lectures provided via mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, Barcelona, Spain, 1–3 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tregonning, A.M.; Doherty, D.A.; Hornbuckle, J.; Dickinson, J.E. The audience response system and knowledge gain: A prospective study. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, e269–e274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D. Clickers in the Classroom; Addison-Wesley: Upper Saddle, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, P.; Tong, A. Digital Devices in Classroom–Hesitations of Teachers-to-be. Electron. J. e-Learn. 2012, 10, 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Katsioudi, G.; Kostareli, E. A Sandwich-model experiment with personal response systems on epigenetics: Insights into learning gain, student engagement and satisfaction. FEBS Open Bio 2021, 11, 1282–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D. Can technology improve large class learning? The case of an upper-division business core class. J. Educ. Bus. 2013, 88, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.J.; Walker, J.; Bauer, T.; Zhao, M. Facilitating Classroom Economics Experiments with an Emerging Technology: The Case of Clickers. 2007. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=989482 (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Hayter, J.; Rochelle, C.F. Clickers: Performance and Attitudes in Principles of Microeconomics. 2013. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2226401 (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- López, L.B.; Pérez, A.M.F.; León, E.F.; Varo, M.E.F.; Rodríguez, M.D.L. Using Interactive Response Systems in Economics: Utility and factors influencing students’ attitudes. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Soc. Technol. Sci. 2017, 4, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A. Significant returns in engagement and performance with a free teaching app. J. Econ. Educ. 2016, 47, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahba, A.A.; Alashban, Z.; Sales, I.; Sherif, A.Y.; Yusuf, O. Development and Evaluation of Interactive Flipped e-Learning (iFEEL) for Pharmacy Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tretter, J.T.; Windram, J.; Faulkner, T.; Hudgens, M.; Sendzikaite, S.; Blom, N.A.; Hanseus, K.; Loomba, R.S.; McMahon, C.J.; Zheleva, B.; et al. Heart University: A new online educational forum in paediatric and adult congenital cardiac care. The future of virtual learning in a post-pandemic world? Cardiol. Young 2020, 30, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.A.; Waghel, R.C.; Dinkins, M.M. Flipped classroom versus a didactic method with active learning in a modified team-based learning self-care pharmacotherapy course. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2019, 11, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; Islam, M.A.; Ahmed, M.; Bashir, R.; Ibrahim, R.; Al-Nemiri, S.; Babiker, E.; Mutasim, N.; Alolayan, S.O.; Al Thagfan, S.; et al. Validation of the Arabic Version of General Medication Adherence Scale (GMAS) in Sudanese Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 4235–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal, A.; Aithal, P. Development and Validation of Survey Questionnaire & Experimental Data—A Systematical Review-based Statistical Approach. Int. J. Manag. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2020, 5, 233–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ohsato, A.; Seki, N.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Moross, J.; Sunaga, M.; Kabasawa, Y.; Kinoshita, A.; Morio, I. Evaluating e-learning on an international scale: An audit of computer simulation learning materials in the field of dentistry. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T. Teaching evaluation and student response rate. PSU Res. Rev. 2018, 2, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, R. Effect of type of schooling and gender on sociability and shyness among students. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2017, 26, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleditch, P.; Moindrot, W. Using classroom response systems for creative interaction and engagement with students. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2015, 3, 1119368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemi, M.K. Clickenomics: Using a classroom response system to increase student engagement in a large-enrollment principles of economics course. J. Econ. Educ. 2009, 40, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Renna, F. Using electronic response systems in economics classes. J. Econ. Educ. 2009, 40, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordes, S.J., Jr.; Gandhi, J.; Bauer, B.; Protas, M.; Solomon, N.; Bogdan, L.; Brummund, D.; Bass, B.; Clunes, M.; Murray, I.V.J. Using lectures to identify student misconceptions: A study on the paradoxical effects of hyperkalemia on vascular smooth muscle. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2020, 44, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouw, J.W.; Gupta, V.; Hincapie, A.L. Assessment of students’ satisfaction with a student-led team-based learning course. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2015, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).