Incremental Innovation: Long-Term Impetus for Design Business Creativity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- (1)

- focusing on people and their context to create something that works for them.

- (2)

- understanding and resolving the correct issue, the underlying cause, and the root problem. Otherwise, problems will continue to return.

- (3)

- all things are systems: consider the world as an interconnected system.

3. Methods

- (1)

- the initiation strategy of incremental innovation.

- (2)

- the process of incremental innovation.

- (3)

- the decision making for incremental innovation.

4. Case Study

4.1. Apple’s Incremental Innovation Strategy

4.2. Benefits of Incremental Creative Thinking

- Maintaining competitiveness: Every product of the next generation must be competitive; this is a necessity. To continue competing with the previous generation, the product must evolve.

- Ideas are more readily available to the market: when offering a recognizable product to an established market, communicating and selling innovative concepts are easier.

- Affordability: The process of incremental innovation makes development afford-able. Products can be more affordably improved.

5. Discussion

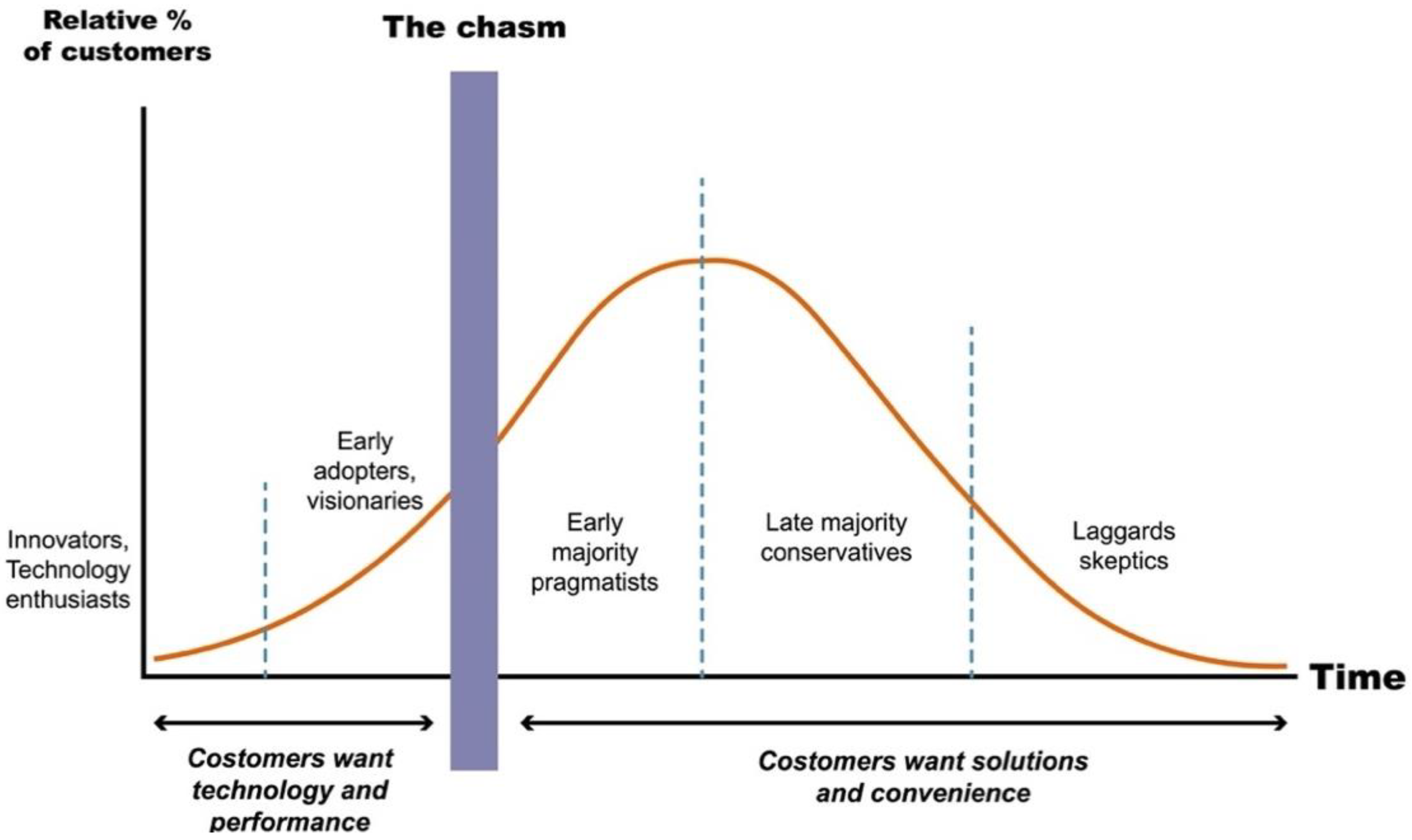

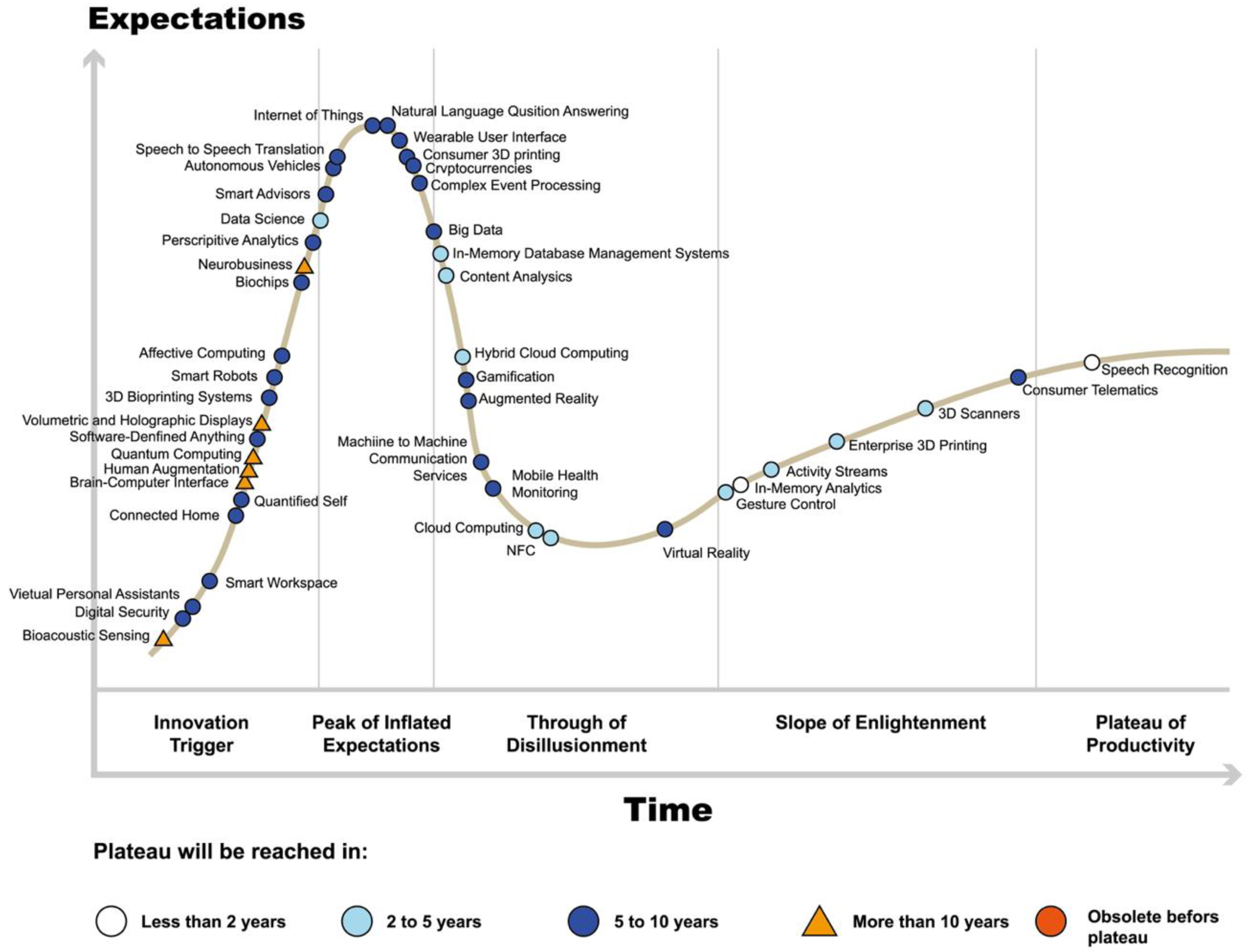

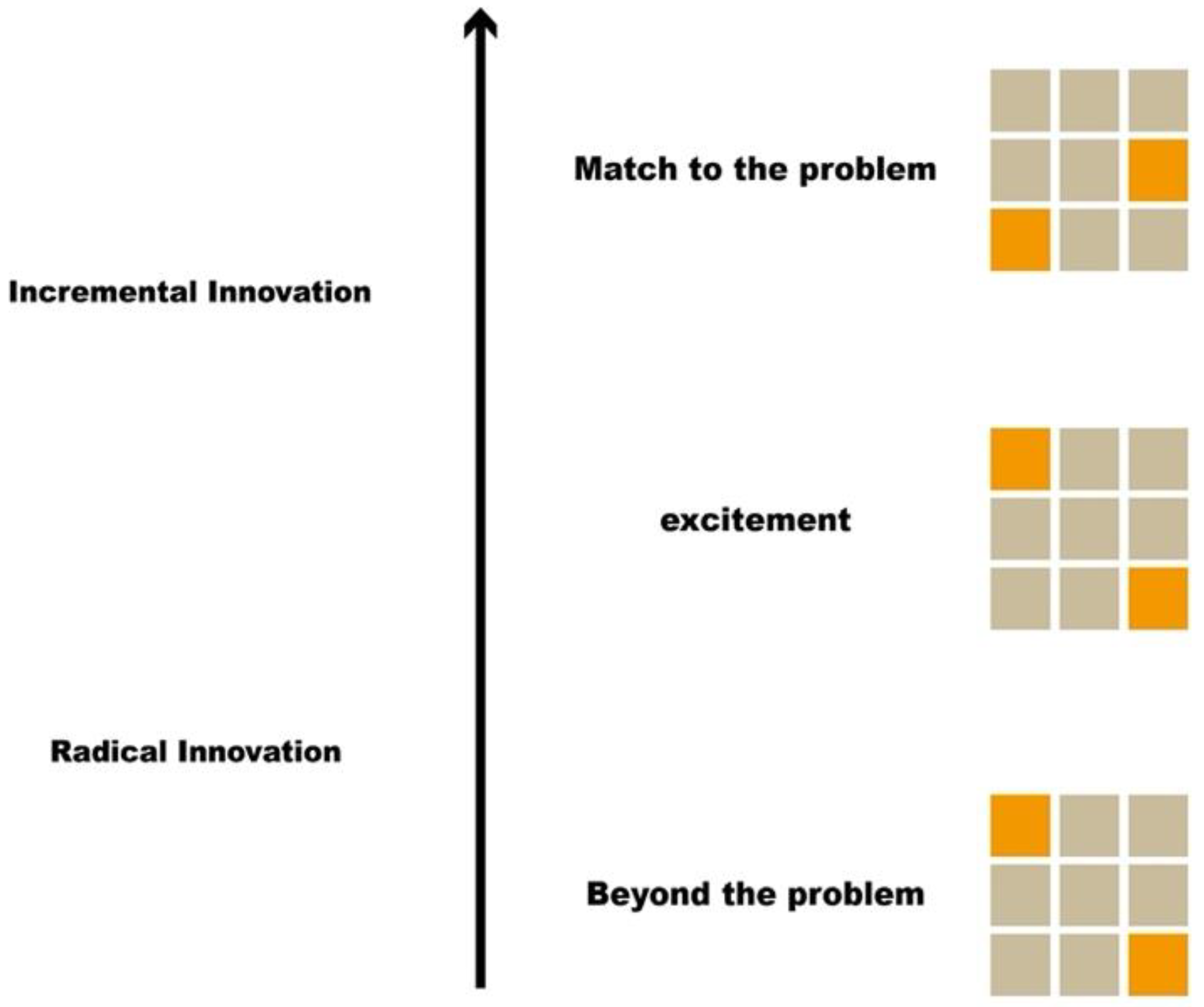

5.1. Initiation of Incremental Innovation

5.2. Clear Examination and SMART Principles

- Communicate a comprehension of the needs and engage the appropriate people in synchronization and discussion.

- The designer verifies that everyone is on the same page by reviewing what is understood.

- Graphically communicate by using sketches or pertinent case illustrations to reduce the possibility of misinterpretation.

- Document what has been agreed upon so that the document can be cross-referenced and later initiated.

5.3. Propositional Focus and Concrete Substitution for Abstraction

6. Process of Incremental Innovation

- There are no close calls. All thoughts must be recorded because many concepts that originally appear unfeasible or unsophisticated might transform into great concepts when they collide or are analyzed.

- Quantity surpasses quality. Obstacles and bottlenecks may arise when ideas evolve, so ideas must be continually developed without settling for the ones that already exist.

- No criticism, no stifling. Any possibilities should not be denied during the idea development phase so that the team or individual can feel safe to develop.

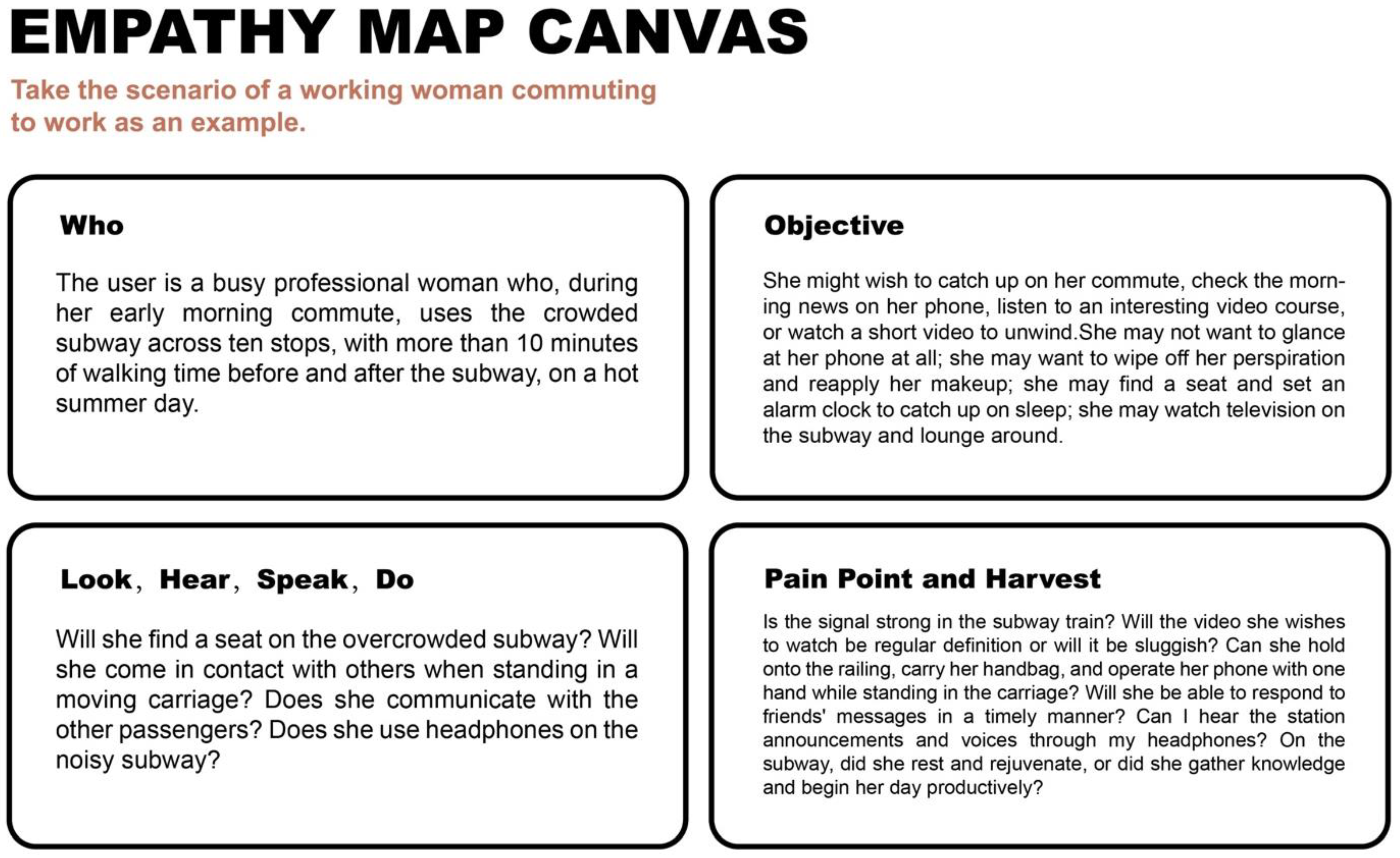

6.1. Persona and Canvas Empathy Map

- (1)

- Consider this virtual persona a genuine user and accordingly enhance the essential information: age, gender, nation, region of residence, profession, marital status, hobbies, leisure time, life experience, perspective, etc. The individual may have a penchant for vacation destinations distinct from their original typical habitat. Their age and status may influence when and with whom they travel: a minor is more likely to travel with their family during the summer and winter holidays, whereas a white-collar professional may take time off during holidays or off-season to travel with their partner or closest friend.

- (2)

- Profiling interests, influences, and goals for more profound discovery are based on the above basic information. If a person likes music, they may want to visit a local live music establishment; if they like history, they may want to walk around the monuments. Their influence may help to motivate the strategy; perhaps many friends or fans are waiting for their journey to be shared on social networks. What are their goals for the trip? They may want to relax with friends and have a slow-paced experience, or they may want to visit the famous sites and fill their schedule.

- (3)

- Determine their wants, expectations, motivations, and criticisms. The person may be searching for a product that merges travel options and accommodations with a coherent strategy and efficiency, encouraging and allowing them to organize without excessive effort. They may be interested in a product that allows them to visit whenever they want, bringing them niche spots to explore nearby so that they and their friends can freely and romantically explore, taking many pictures to remember and share.

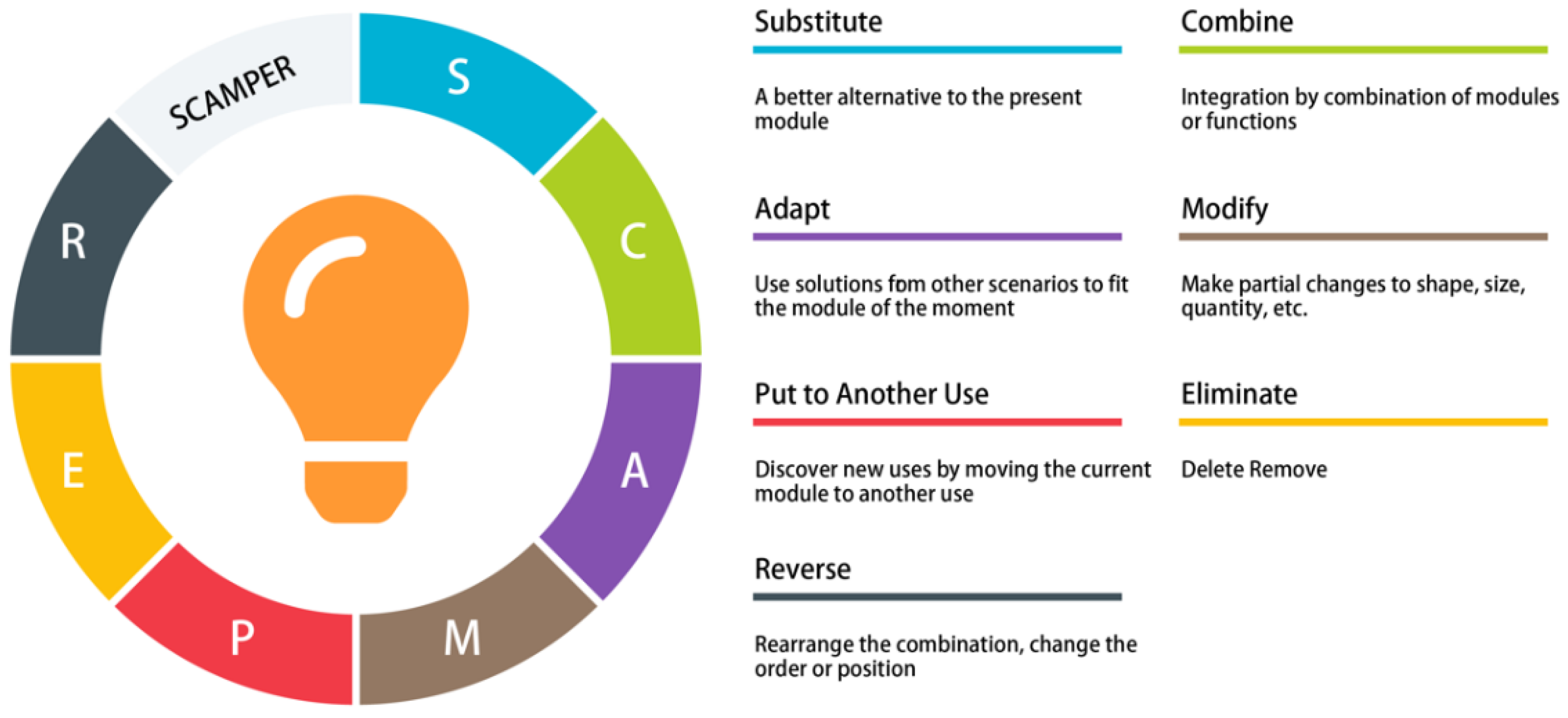

6.2. Modularization and SCAMPER

6.3. Reverse Thinking: Principle, Function, and Structure

6.4. Borrowing from Other Areas of Thinking

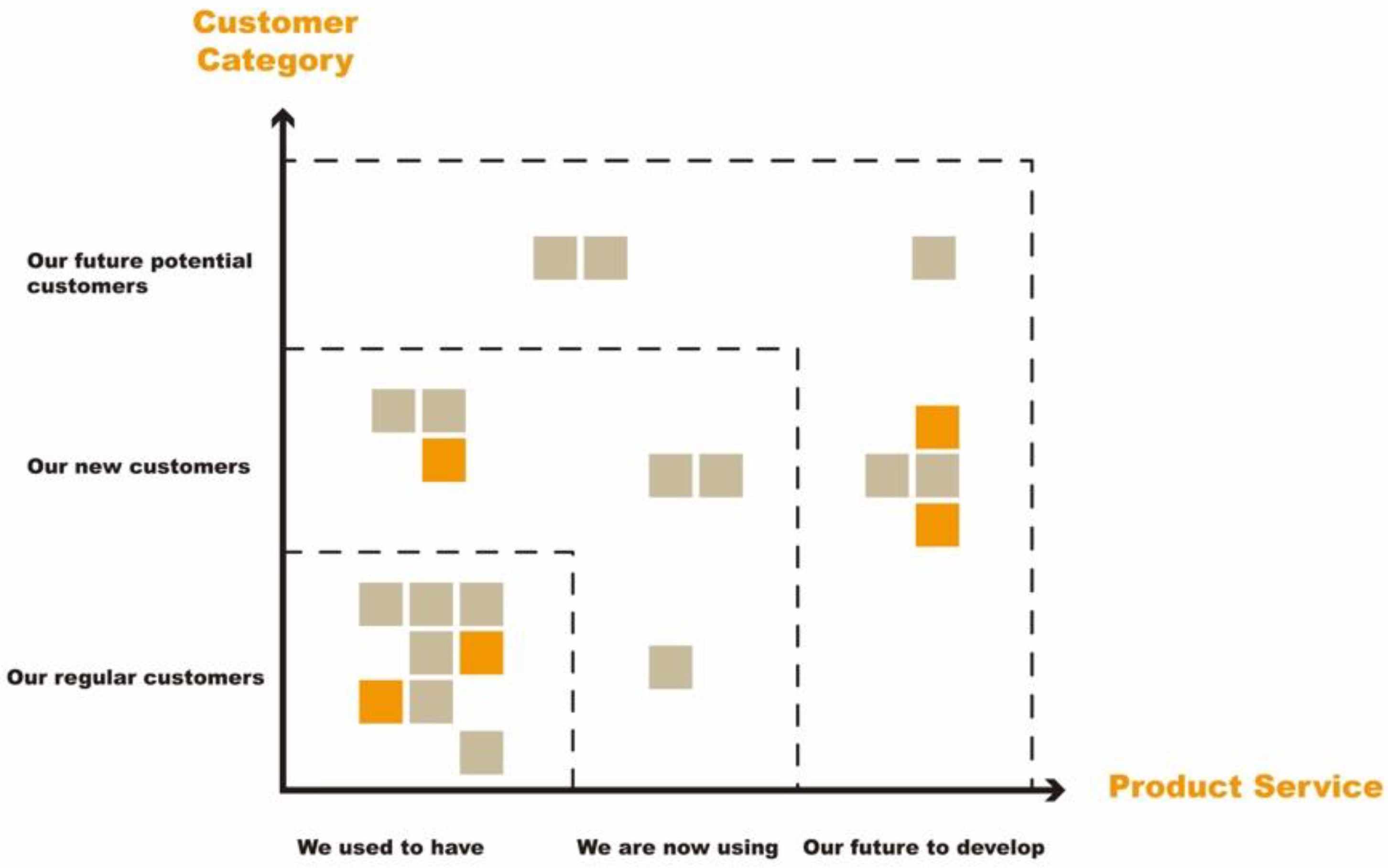

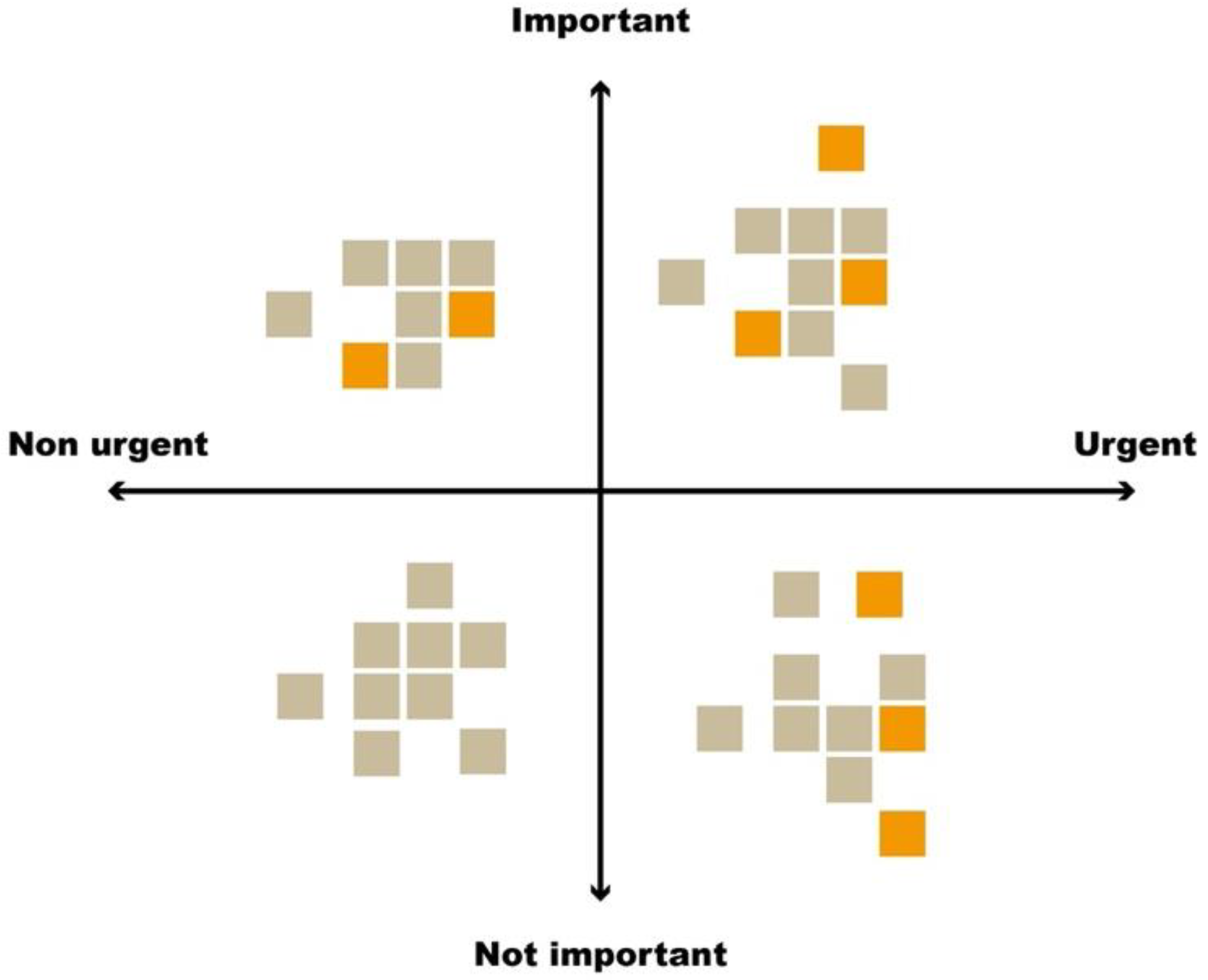

7. Decision of Progressive Innovation

7.1. Structured Screening

7.2. Produce Prototypes and Iterate with Agilely

- (1)

- Functional Prototype: test critical variables for the experience of crucial functions, create the minimum viable product (MVP), and then conduct intensive testing on potential users.

- (2)

- Finished Prototype: integrate the scattered functional prototypes so that users can experience the overall interaction for feedback.

- (3)

- Final Prototype: collect feedback and adjustments from previous prototypes and further refine them, usually with a high level of commitment and realization.

7.3. Most Advanced Yet Acceptable

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Escrig-Tena, A.B.; Segarra-Ciprés, M.; García-Juan, B. Incremental and radical product innovation capabilities in a quality management context: Exploring the moderating effects of control mechanisms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 232, 107994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Guang, L.; Bin, L.; Li, R. Innovative Design of Intelligent Health Equipment for Helping the Blind in Smart City. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 3193193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trischler, J.; Westman Trischler, J. Design for experience—A public service design approach in the age of digitalization. Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 1251–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeke-Freund, F. Sustainable entrepreneurship, innovation, and business models: Integrative framework and propositions for future research. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 665–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing your business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Tiberius, V.; Schwarzer, H.; Roig-Dobón, S. Radical innovations: Between established knowledge and future research opportunities. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J. Informatization, Micro-Innovation and Dynamic Competitive Advantage. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2021, 11, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cao, Q.; Qin, L.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, T.; Feng, L. Uncertain environment, dynamic innovation capabilities and innovation strategies: A case study on Qihoo 360. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 95, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.; Geradts, T.H. Barriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, K. Creative Burst: A Practical Method for UX Design Teams to Drive Innovation Product Strategy from Within; Insightful Scribbles: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bierwisch, A.; Huter, L.; Pattermann, J.; Som, O. Taking Eco-Innovation to the Road—A Design-Based Workshop Concept for the Development of Eco-Innovative Business Models. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixanet, J.; Rialp, J. Disentangling the relationship between internationalization, incremental and radical innovation, and firm performance. Glob. Strategy J. 2022, 12, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaker, T.; Ly, P.T.M.; Nguyen-Thanh, N.; Nguyen, H.T.H. Business model innovation through the application of the Internet-of-Things: A comparative analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlander, L.; Gann, D.M.; Wallin, M.W. How open is innovation? A retrospective and ideas forward. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilli, M.D.; Balavac, M.; Radicic, D. Business innovation modes and their impact on innovation outputs: Regional variations and the nature of innovation across EU regions. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, M. How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dziallas, M.; Blind, K. Innovation indicators throughout the innovation process: An extensive literature analysis. Technovation 2019, 80, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopp, A.R.; Parisi, K.E.; Munson, S.A.; Lyon, A.R. A glossary of user-centered design strategies for implementation experts. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, S.; Peters, A.; Bardzell, S.; Burnett, M.; Busse, D.; Cauchard, J.; Churchill, E. Gender-inclusive HCI research and design: A conceptual review. Found. Trends Hum. Comput. Interact. 2020, 13, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, P. Reinventing innovation management: The impact of self-innovating artificial intelligence. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 68, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Fujimoto, T. Frugal innovation and design changes expanding the cost-performance frontier: A Schumpeterian approach. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1016–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Boura, M.; Lekakos, G.; Krogstie, J. The role of information governance in big data analytics driven innovation. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

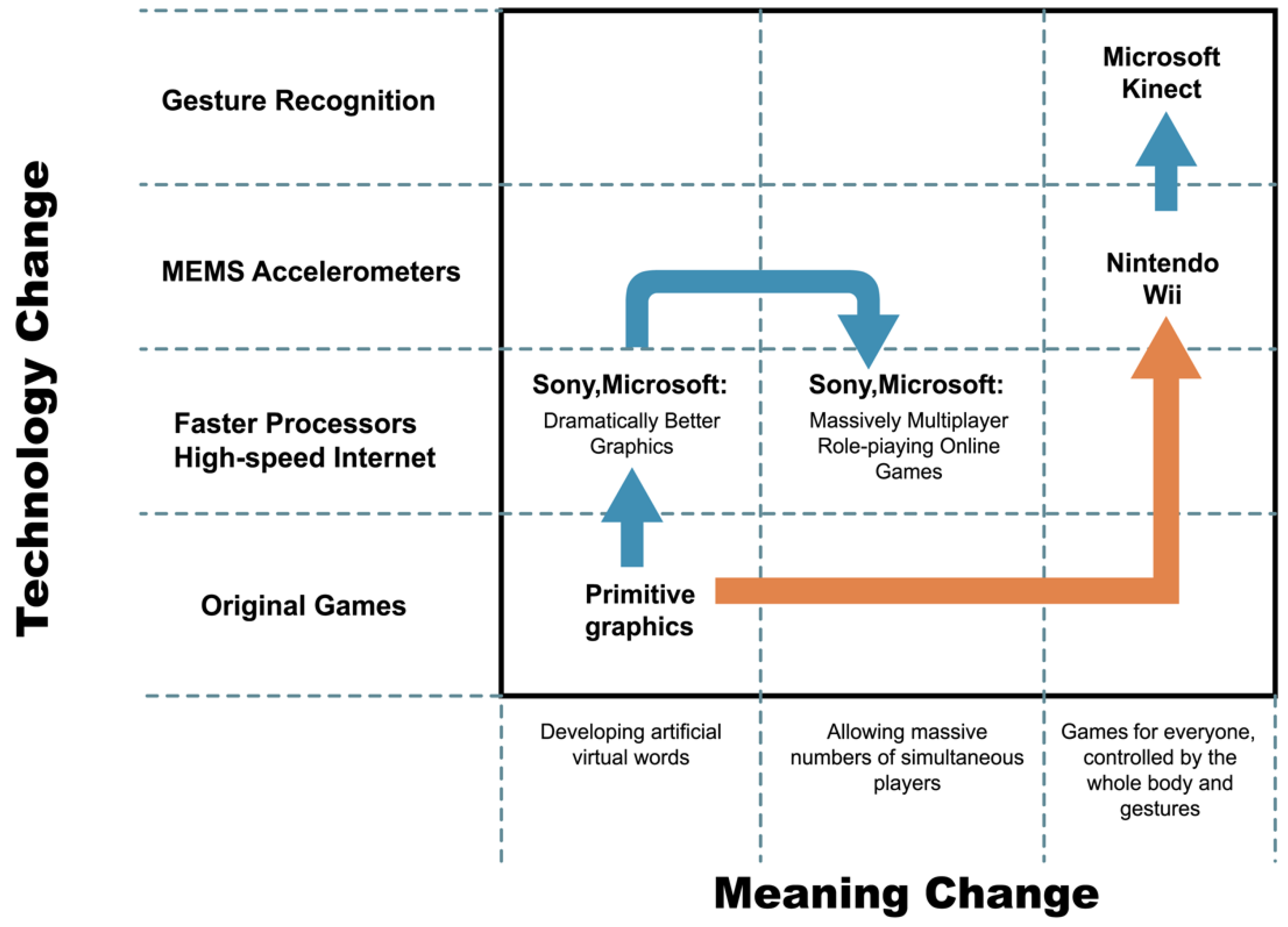

- Norman, D.A.; Verganti, R. Incremental and radical innovation: Design research vs. technology and meaning change. Des. Issues 2014, 30, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keränen, O.; Komulainen, H.; Lehtimäki, T.; Ulkuniemi, P. Restructuring existing value networks to diffuse sustainable innovations in food packaging. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampa, R.; Agogué. Developing radical innovation capabilities: Exploring the effects of training employees for creativity and innovation. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2021, 30, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M.; Shaabani, A.; Valaei, N. An integrated fuzzy framework for analyzing barriers to the implementation of continuous improvement in manufacturing. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2020, 38, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissman, J.; Bataille, C.; Masanet, E.; Aden, N.; Morrow, W.R., III; Zhou, N.; Elliott, N.; Dell, R.; Heeren, N.; Huckestein, B.; et al. Technologies and policies to decarbonize global industry: Review and assessment of mitigation drivers through 2070. Appl. Energy 2020, 266, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Coraiola, D.; Harvey, C.; Foster, W. History and the micro-foundations of dynamic capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 530–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Qu, X.; Tian, S.; Ma, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, Y. Artificial intelligence empowerment: The impact of research and development investment on green radical innovation in high-tech enterprises. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 39, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziurski, P.; Mierzejewska, W. Innovation Strategy. In Critical Perspectives on Innovation Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren, C. The cumulative power of incremental innovation and the role of project sequence management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodoveo, M.L.; Crupi, P.; Corbo, F. Olive Sound: A sustainable radical innovation. Processes 2021, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.S.; Wang, W.Y.; Chan, T.C.; Chiu, Y.L.; Lin, H.C.; Chang, Y.T.; Wu, H.A.; Liu, T.Z.; Chuang, Y.U.; Wu, J.; et al. Effect of the Nintendo Ring Fit Adventure Exergame on Running Completion Time and Psychological Factors among University Students Engaging in Distance Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games 2022, 10, e35040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Fabini, T.; Kovacs, B.; Hell, T.; Rutzinger, S.; Schinegger, K. Hybrid Immediacy: Designing with Artificial Neural Networks Through Physical Concept Modelling. In Towards Radical Regeneration: Design Modelling Symposium Berlin 2022; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Tan, R.; Peng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, J. Radical innovation of product design using an effect solving method. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forés, B.; Camisón, C. Does incremental and radical innovation performance depend on different types of knowledge accumulation capabilities and organizational size? J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Fredrich, V.; Ritala, P.; Kraus, S. Coopetition in new product development alliances: Advantages and tensions for incremental and radical innovation. Br. J. Manag. 2017, 29, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritala, P.; Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. Incremental and radical innovation in coopetition—The role of absorptive capacity and appropriability. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Wicki, S.; Schaltegger, S. Sustainability-oriented technology exploration: Managerial values, ambidextrous design, and separation drift. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 26, 2240004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, K.; Jayasimha, K.R. Buying behaviour model of early adopting organizations of radical software innovations. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2020, 36, 1010–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Mohr, J.J.; Sengupta, S. Radical product innovation capability: Literature review, synthesis, and illustrative research propositions. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenner, N.F.; Gemser, G.; Karpen, I.O. Entrepreneurial ways of designing and designerly ways of entrepreneuring: Exploring the relationship between design thinking and effectuation theory. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2022, 39, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.W.; Norman, D. Changing design education for the 21st century. She Ji: J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2020, 6, 13–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosoni, I. Innovation Capacity and the City: The Enabling Role of Design; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Gribbin, J.J. Adopting Design-Led Innovation: A Study of Integrating Design Practices into the Innovation Process of Multinational Science and Technology-Led Firms; University of Northumbria: Newcastle, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, S.; Obal, M. Investigating the impact of radical technology adoption into the new product development process. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 2050035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajarmeh, N. Non-visual access to mobile devices: A survey of touchscreen accessibility for users who are visually impaired. Displays 2021, 70, 102081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yu, K. Moore’s law and price trends of digital products: The case of smartphones. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2020, 29, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerick, T. Extreme Entrepreneurs: Steve Jobs and Jesus Christ; Page Publishing Inc.: Conneaut Lake, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Jiang, S.; Liang, X. Competing value framework-based culture transformation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A.F.S.; Omar, A.; Abdulammeer, H.D. Employees’ Performance on Apple Company. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, B.S.; Lee, S.G.; Aoshima, Y. An analysis of the trilemma phenomenon for Apple iPhone and Samsung Galaxy. Serv. Bus. 2019, 13, 779–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolny, J.M.; Hansen, M.T. How Apple is organized for innovation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 98, 86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, U.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, S.; Tse, J.; Lee, H.H.S.; Wei, G.Y.; Brooks, D.; Wu, C.A. Chasing carbon: The elusive environmental footprint of computing. IEEE Micro 2022, 42, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merazzo, K.J.; Totoricaguena-Gorriño, J.; Fernández-Martín, E.; Del Campo, F.J.; Baldrich, E. Smartphone-Enabled Personalized Diagnostics: Current Status and Future Prospects. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; García-Maroto, I.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Ramos-de-Luna, I. Mobile payment adoption in the age of digital transformation: The case of Apple Pay. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishti, S.; Craddock, T.; Courtneidge, R.; Zachariadis, M. (Eds.) The PAYTECH Book: The Payment Technology Handbook for Investors, Entrepreneurs, and FinTech Visionaries; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.M.; Ho, H. Who pays you to be green? How customers’ environmental practices affect the sales benefits of suppliers’ environmental practices. J. Oper. Manag. 2019, 65, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaarschmidt, M.; Homscheid, D.; Kilian, T. Application developer engagement in open software platforms: An empirical study of Apple iOS and Google Android developers. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 23, 1950033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, J.; Maresch, D.; Tierney, R. The key to scaling in the digital era: Simultaneous automation, individualization and interdisciplinarity. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. Different determinants affecting first mover advantage and late mover advantage in a smartphone market: A comparative analysis of Apple iPhone and Samsung Galaxy. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyanathan, N.; Henningsson, S. Designing augmented reality services for enhanced customer experiences in retail. J. Serv. Manag. 2022. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.R.; Bakar, A.A.; Yaakub, M.R. Ant colony optimization for text feature selection in sentiment analysis. Intell. Data Anal. 2019, 23, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Ribiere, V. Developing a unified definition of digital transformation. Technovation 2021, 102, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanke, M. Retail Isn’t Dead: Innovative Strategies for Brick and Mortar Retail Success; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gerea, C.; Gonzalez-Lopez, F.; Herskovic, V. Omnichannel customer experience and management: An integrative review and research agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Ahn, H.J.; Lee, D.S.; Park, K.B.; Zhao, X. Inter-rationality; Modeling of bounded rationality in open innovation dynamics. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 184, 122015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Sousa, E.; Rodrigues, C.; Candeias, M.B.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Samsung vs. Apple: How Different Communication Strategies Affect Consumers in Portugal. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallstedt, S.I.; Isaksson, O.; Öhrwall Rönnbäck, A. The need for new product development capabilities from digitalization, sustainability, and servitization trends. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, P. Design aesthetics: Principles of pleasure in design. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 48, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Loučanová, E.; Olšiaková, M.; Štofková, J. Open Business Model of Eco-Innovation for Sustainability Development: Implications for the Open-Innovation Dynamics of Slovakia. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindauer, M.; Larimore, T.; LeBoeuf, M. The Bogleheads’ Guide to Investing; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.S.; Lin, H.C.; Chien, Y.H.; Yen, W.H. Effects of creative components and creative behavior on design creativity. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 29, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, G.; Nagai, Y.; Georgiev, G.V.; Zelaya, J.; Becattini, N.; Boujut, J.F.; Casakin, H.; Crilly, N.; Dekoninck, E.; Gero, J.; et al. Perspectives on design creativity and innovation research: 10 years later. Int. J. Des. Creat. Innov. 2022, 10, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loučanová, E.; Šupín, M.; Čorejová, T.; Repková-Štofková, K.; Šupínová, M.; Štofková, Z.; Olšiaková, M. Sustainability and branding: An integrated perspective of eco-innovation and brand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiola, M.; Agostini, L.; Grandinetti, R.; Nosella, A. The process of business model innovation driven by IoT: Exploring the case of incumbent SMEs. Ind. Market. Manag. 2022, 103, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, R.; John, K. Commercializing Academic Medical Research: The Role of the Translational Designer. Des. J. 2019, 22, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sull, D.; Sull, C. With goals, FAST beats SMART. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2018, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub, J.; Cassell, D.; DePatie, T.P. Nudging flow through ‘SMART’goal setting to decrease stress, increase engagement, and increase performance at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 94, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, T.M.; Pogge, E.K.; Early, N.K.; Larson, S.; Stein, J.; Hanson, L.; Storjohann, T.; Raney, E.; Davis, L.E. Evaluating the impact of integrating SMART goal setting in preceptor development using the Habits of Preceptors Rubric. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, D. 5.7. SMART Goals in Projects. In Strategic Project Management; Fanshawe College: London, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, G.T. There is a SMART way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manag. Rev. 1981, 70, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shé, C.N.; Farrell, O.; Brunton, J.; Costello, E. Integrating design thinking into instructional design: The case study. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 38, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pileggi, S.F. Knowledge interoperability and re-use in Empathy Mapping: An ontological approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 180, 115065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrine, S.L.; Fugate, J.M. (Eds.) Movement Matters: How Embodied Cognition Informs Teaching and Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Souto, J.E. Organizational creativity and sustainability-oriented innovation as drivers of sustainable development: Overcoming firms’ economic, environmental and social sustainability challenges. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 33, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Ritter, S.M.; Delfmann, L.R.; Dijksterhuis, A. Stimulating Creativity: Examining the Effectiveness of Four Cognitive-based Creativity Training Techniques. J. Creat. Behav. 2022, 56, 312–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, K.; Valença, G.; Alessio, P.; Formiga, R.; Neves, A.; Lacerda, N. The Developers’ Design Thinking Toolbox in Hackathons: A Study on the Recurring Design Methods in Software Development Marathons. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, R. Design Thinking as a Problem Solving Tool. In The Handbook of Creativity & Innovation in Business; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, M.; Martínez, M.V.D.C.; Martínez, E.M.; López-Sanz, M.; Martín-Peña, M.L. Driving organisational change in SMEs using service design. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2022. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaitis, R.; Longaphy, J.; Ploeg, J.; Agarwal, G.; Oliver, D.; Nair, K.; Kastner, M.; Avilla, E.; Dolovich, L. Health TAPESTRY: Co-designing interprofessional primary care programs for older adults using the persona-scenario method. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wible, S. Using design thinking to teach creative problem solving in writing courses. Coll. Compos. Commun. 2020, 71, 399–425. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenbart, B.; Bouwman, S.; Voorendt, J.; McKillagan, S.; Kuys, B.; Ranscombe, C. Implementing design thinking to drive innovation in technical design. Int. J. Design Creat. Innov. 2022, 10, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.T.; Wu, Y.T. Applying project-based learning and SCAMPER teaching strategies in engineering education to explore the influence of creativity on cognition, personal motivation, and personality traits. Think. Ski. Creat. 2020, 35, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapiro, E. A Framework for Understanding How People Can Draw Different Conclusions Based on the Same Information. Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection. 2022. Available online: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone/401/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Kuypers, K.P.C. Out of the box: A psychedelic model to study the creative mind. Med. Hypotheses 2018, 115, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brucker, B.; Brömme, R.; Ehrmann, A.; Edelmann, J.; Gerjets, P. Touching digital objects directly on multi-touch devices fosters learning about visual contents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynski, R. Headphone Audio in Training Systems or Systems That Convey Important Sound Information. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malodia, S.; Gupta, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Reverse innovation: A conceptual framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 1009–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.K.; Root, J.R. Modified schema-based instruction to develop flexible mathematics problem-solving strategies for students with autism spectrum disorder. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2020, 41, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, D.B.; Blair, K.P.; Wolf, R.C.; Conlin, L.D.; Cutumisu, M.; Pfaffman, J.; Schwartz, D.L. Educating and measuring choice: A test of the transfer of design thinking in problem solving and learning. J. Learn. Sci. 2019, 28, 337–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.J. First-Run Syndication and Unwired Networks in the 1980s: Viacom’s Superboy and Buena Vista TV’s DuckTales. Telev. New Media 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatam, S. Evolutionary Ideas: Unlocking Ancient Innovation to Solve Tomorrow’s Challenges; Harriman House Limited: Petersfield, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kummitha, R.K.R. Design thinking in social organizations: Understanding the role of user engagement. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2019, 28, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinyi, Y. An Analysis on Driving Forces and Impacts of the Commercial Mode of Digital Music—A Comparison between QQ Music and iTunes. Acad. J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y. Computer Analysis and Automatic Recognition Technology of Music Emotion. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 3145785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, W.; Edler, J. Demand, challenges, and innovation. Making sense of new trends in innovation policy. Sci. Public Policy 2018, 45, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Keränen, J.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L. How B2B suppliers articulate customer value propositions in the circular economy: Four innovation-driven value creation logics. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 87, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.; McManus, R. Discovery-Driven. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 98, 124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Venkatesh, P.; Lim, B.Y. Interpretable Directed Diversity: Leveraging Model Explanations for Iterative Crowd Ideation. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Kyushu University: Fukuoka, Japan, 2022; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuizen, T.L.; Bakker, T.; Postma, T.J. Implementing new business models: What challenges lie ahead? Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellas, J.K.; Baker, J.; Cardwell, M.; Minniear, M.; Horstman, H.K. Communicated perspective-taking (CPT) and storylistening: Testing the impact of CPT in the context of friends telling stories of difficulty. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 38, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Oivo, M.; Liukkunen, K.; Markkula, J. Startup ecosystem effect on minimum viable product development in software startups. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2019, 114, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobni, C.B.; Sand, C. Strategy shift: Integrating strategy and the firm’s capability to innovate. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisape, D. The platform business model canvas a proposition in a design science approach. Am. J. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2019, 4, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Wakuta, Y. How digital platform leaders can foster dynamic capabilities through innovation processes: The case of taobao. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Radical Innovation | Incremental Innovation |

|---|---|

| Explores new technology [23] | Exploits existing technology [23] |

| High uncertainty [12] | Low uncertainty [12] |

| Focuses on products, processes, or services with unprecedented performance feature [20] | Focuses on cost or feature improvements in existing processes, products, or services [20] |

| Creates a dramatic change that transforms existing markets or industries, or creates new ones [24] | Improves competitiveness within current markets or industries [22] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X. Incremental Innovation: Long-Term Impetus for Design Business Creativity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214697

Zhang X. Incremental Innovation: Long-Term Impetus for Design Business Creativity. Sustainability. 2022; 14(22):14697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214697

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xi. 2022. "Incremental Innovation: Long-Term Impetus for Design Business Creativity" Sustainability 14, no. 22: 14697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214697

APA StyleZhang, X. (2022). Incremental Innovation: Long-Term Impetus for Design Business Creativity. Sustainability, 14(22), 14697. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214697