Abstract

For many years, the concept of sustainability and luxury has been considered a paradox. Despite scholars’ efforts to highlight the compatibility between sustainability and luxury, the limited studies have shown mixed and inconclusive evidence. By adopting the luxury-seeking consumer behavior framework, this study examines the relationship between luxury value perceptions (i.e., conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values) and sustainable luxury products consumption. It also identifies the value dimensions that most discriminate between heavy and light consumers of sustainable luxury products and examines the moderating effects of consumer income. Using 348 survey responses from actual consumers of luxury goods in Qatar, hierarchical multiple regression and discriminant analyses were conducted to test the hypothesized relationships. The results suggest that all five value perceptions explain a significant amount of variance in sustainable luxury consumption and discriminate between heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers. However, the moderating effects of consumer income in the relationship between values and sustainable luxury consumption revealed mixed results. The findings of this research provide key theoretical and managerial implications.

1. Introduction

For many years, the concept of sustainability and luxury has been considered a paradox. Sustainability is associated with concern for the society and environment, while luxury is associated with waste and extravagance, especially when its main or only purpose is to signal wealth and affluence. Consumers’ tendency to purchase goods and services mainly for the status or social prestige value that they confer on their owners [1] is deemed frivolous, self-indulgent, and wasteful by some. Some scholars of luxury goods recognize their ability to signal status and have promulgated the signaling theory as a theoretical lens for understanding luxury consumption and the motives of such consumers. Yet, other scholars reason that luxury and sustainability can actually complement each other [2,3,4,5,6], and that luxury consumption can also signal sustainability. Considering that luxury contributes positively to individuals and the environment, in a way that other products cannot, this rather novel perspective of luxury is gradually gaining recognition. Luxury brands can sway consumer aspiration and behavior by modifying consumer choices through the design, distribution, and marketing of their product, as well as by affecting when, how, and for how long consumers use their products [7]. Hence, luxury brands have a pivotal role to play in sustainable development, which refers to meeting “the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [8] (p. 43).

Accordingly, a paradigm shift is currently taking place as luxury fashion brands work diligently to improve their sustainability and adopt it as part of the luxury essence [3,9]. This is not to say that luxury brands are greenwashing, but rather truly incorporting sustainable development into the whole value chain [10]. For example, Gucci established a program (i.e., Gucci Equilibrium) that tracks the company’s corporate social responsibility, environmental impact, structural innovation, and employee satisfaction; Stella McCartney developed biodegradable and recycled materials in an effort to eschew leather and fur and promote cruelty-free fashion; and Levi’s launched a campaign (i.e., “buy better, wear longer”) to raise awareness about the environmental impacts of the fashion industry and encourage sustainable fashion production practices. However, the success of this movement towards sustainable development depends on people’s ability to consume in a sustainable manner [11]. There is also the need for more consumers to see the compatibility of luxury and sustainable consumption, rather than the paradox that many see currently.

Sustainable consumption implies a change in consumption patterns that involves reducing the frequency of purchase, extending the product usage, and even engaging in shared use so as to secure future generations’ needs [12]. However, promoting such consumption patterns is difficult for fashion-focused consumer products as fashion trends and items tend to change frequently. Fast fashion in particular, also called waste culture [13], has encouraged overconsumption and disposal behaviors, whereby the frequency of purchase is rising while the usage of items is declining [14]. Such a phenomenon pushes consumers to choose quantity over quality, which in turn continuously reduces the price one is willing to pay for an item, leading fashion brands to engage in unethical practices. The lower prices encourage consumers to consider these items, worn once or twice, as disposable, especially past-seasoned items [13,14]. These items end up in landfills, worsening the environmental harm. Therefore, to counteract this phenomenon, researchers have suggested that luxury fashion brands can influence consumers to engage in sustainable consumption by purchasing their quality products that are timeless in style, and thus do not need to be replaced as often [5,15,16].

A recent systematic literature review by Athwal et al. [9] revealed that only a limited number of studies have explored the link between sustainability and luxury. For example, some studies [17,18,19] found that consumers generally do not consider sustainability when buying luxury products and evaluate luxury products made from sustainable materials negatively. Other studies nonetheless [4,15] posit that features such as durability and scarcity of luxury goods are in alignment with sustainability. These findings imply that although some consumers believe luxury products with sustainable features only fulfill functional needs, neglecting other consumer needs, others are of the view that luxury consumption promotes sustainability, thus adding additional value. These mixed empirical results of existing studies on the complementarity of luxury and sustainability call for further investigation.

As the debate has centered mostly on whether luxury is even compatible with sustainability, researchers have paid little attention to understanding the sustainability-related motives of luxury consumers viz. “how” and “why” they engage in sustainable consumption. For instance, Cervellon and Shammas [2], using elicitation techniques, revealed that a few luxury values (e.g., conspicuousness, durable quality) can be enhanced by sustainable luxury. Similarly, Wang et al. [6] highlighted that social luxury values (exclusivity, conformity, and hedonic needs) impact consumers’ purchase intentions towards sustainable luxury. Therefore, there is a lack of understanding as to what drives sustainable luxury consumption.

Research addressing the mixed findings of existing studies and the “why” of sustainable consumption is not only theoretically beneficial, but also useful for developing effective strategies for “locking-in” existing luxury consumers, and for converting the fast fashion segment. The present study responds to the above gaps by examining the value perceptions of luxury consumers in Qatar and the influence on their purchasing behaviors, as well as the contingent factors in the said relationship. Specifically, by adopting the luxury-seeking consumer behavior model [20], the study has the following three specific objectives: (1) to examine the relationship between luxury values (namely, conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values) and sustainable luxury consumption; (2) to identify which value dimensions most discriminate between heavy consumers of sustainable luxury and light consumers of sustainable luxury; and (3) to examine the moderating effects of consumer income in the relationship between the five luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption.

Another important aspect of the study is the role of the psychographic, demographic, and behavioral characteristics of sustainable luxury consumers. These are very useful perspectives and help in gaining a deeper understanding of consumer behavior in general, consumption patterns, consumer values, and value segmentation. For example, consumer studies have categorized consumers as light, medium, and heavy users based on their usage behaviors [21,22]. By providing a deeper understanding of heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers and their values through the psychographic, behavioral, and demographic angles, the study makes important theoretical and practical contributions to the limited body of knowledge and marketing practice in the Middle East in particular and developing countries in general. Among the demographic variables, income is a particularly relevant contingency factor to study, since luxury products are usually very expensive and their consumption relies heavily on the consumer’s income, and Qatar boasts the world’s largest income per capita.

Lastly, the paper examines the hypothesized relationship amongst a sample of non-Western consumers based in an emerging economy within the Arabian sub-continent Qatar. Being sensitive to context and perspective helps to mitigate the temptation of conveniently applying theories and findings from developed Western economies to emerging non-Western environments [23]. Indeed, the existing literature proposes that emerging economies offer a greatly attractive setting for investigating consumer behavior and the role of firm strategy on such behaviors and firm performance. As such, an examination of the contingent effects of income in the relationship between luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption from this rich Arabian market is particularly useful. We approach our research by drawing on signaling and values theoretical perspectives. The next sections review the extant literature and theories adopted in this study, followed by the hypothesis development, research methodology, results, discussion, implications, limitations, and future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Signaling Theory

Past studies have reasoned that consumers use luxury consumption to signal status. Eastman et al. define consumption-related need for status as a “tendency to purchase goods and services for the status or social prestige value that they confer on their owners” [1] (p. 41). Status is rooted in ancient society, where one’s place in social hierarchy is attained by birth (through nobility), ordainment (through conferment/award), and more recently achievement and accompanying wealth [24,25]. The notion of consumption-related need for status is based on Veblen’s [26] classical theory of the leisure class, which argues that it is the evidence of wealth through wasteful exhibition (conspicuous luxury consumption) rather than the accumulation of wealth that confers status, thus bringing to the fore consumers’ symbolic motive of consumption [27]. Marketing scholars have long recognized the symbolic role of possessions in the lives of consumers and practitioners have capitalized on such a consumer motive and willingness to pay a premium prize to add “snob appeal” by attaching a high price to an otherwise ordinary product [24]. Bagwell and Bernheim remarked that consumers will pay a higher price for a functionally equivalent good because of a craving for the status that accrues through such material displays of wealth [28]. As such, luxury goods’ ability to signal status has been offered as a plausible explanation for their consumption, by need-for-status-driven consumers at least. As Wernerfelt argued, brand choice can send meaningful social signals to other consumers about the type of person using the brand [29].

Whereas luxury consumption has long been associated with wasteful exhibitions of wealth by need-for status consumers, recent developments have unveiled another genuine motive for luxury consumption—sustainability. This category of consumers is said to buy luxury because of the durability and reliability that makes it not easily replenishable and less wasteful. Thus, they signal their commitment to sustainability by consuming luxury items, which they can keep for a long time and reuse countless times. This motive of consuming luxury products for sustainability purposes contrary to the wasteful notion of luxury consumption has been termed sustainable luxury consumption, which many scholars now consider a paradox. Thus, the signaling theory helps in the understanding of the sustainable luxury paradox.

2.2. Sustainable Luxury Paradox

Consumers’ perceptions of what luxury embodies are constantly changing and fluctuating, making luxury a relative concept [30,31]. Bendell and Kleanthous [7] were the first to envision a deeper value of luxury brands, whereby sustainability is positioned in their core. By mentioning sustainable luxury as a separate construct, the authors have ignited an ongoing debate as to whether luxury can even be in harmony with sustainability [17,18,19,32,33]. Given the association of luxury consumption with personal pleasure, superficiality, excess, ostentation, and conspicuous consumption, the contradictions between the two concepts are evident [9]. Sustainability highlights the importance of conserving natural assets in consumption and business practices. Accordingly, sustainable consumption is repeatedly linked to altruism, sobriety, ethics, and moderation [14,17]. Luxury brands nevertheless often disregard costs in their pursuit of perfect quality and creativity [10]. The essence of luxury value is based on objective scarcity and rarity (e.g., rare materials, leathers, skins, pearls, craftsmanship), which challenges animal welfare and biodiversity [32]. Hence, such products are deemed excessive, non-essential, and extravagant, and criticized for wasting resources that bring pleasure to a “happy few” [10]. Additionally, the inherent high prices of luxury goods are a stark reminder of social inequality. Nevertheless, luxury is traditionally associated with exceptional quality, timelessness, craftsmanship, respect for materials, and greater value [34,35]. Thereby, luxury is the ideal foundation for products that preserve essential environmental and social values [10].

Scholars have started documenting luxury brands’ efforts to incorporate sustainability [9,36,37,38,39] as sustainability can no longer be disregarded by brands [9]. Although consumers expect luxury brands to engage in sustainable practices, it does not necessarily mean that they incorporate sustainability criteria in their luxury purchases [40]. In fact, sustainability, compared to other features, is rarely considered in the selection criteria of luxury brands [17,18,32]. Hence, several empirical findings highlight the incompatibility between sustainability and luxury consumer behavior. For instance, some studies reported that even when consumers say they are sensitive to sustainability issues, they tend to either purposely ignore it when purchasing [41] or are not willing to pay more for it [42]. Indeed, Davies et al. [18] reported that consumers are not even concerned about ethics in luxury purchases as they perceive luxury products to be devoid of ethical issues purely based on the price tag or brand name on the label. Achabou and Dekhili [17] and Dekhili et al. [19] reported that people had negative perceptions of luxury products made from recycled material and associated them with lower quality, even when they believed it is better for the environment. However, Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau [32] argued that the way consumers perceive luxury actually determines the luxury–sustainability compatibility, wherein the contradiction grows when they regard luxury as “creating social unrest” and “superficial”.

To better understand this phenomenon, academics have disintegrated sustainability into sub-elements to demonstrate that some components are in alignment with luxury. Unlike fast fashion, the essence of luxury revolves around timelessness, scarcity, durability, and high quality [7,43]. Thereby, luxury significantly aids in preserving natural resources compared to fast fashion. Indeed, Grazzini et al. [44] revealed that consumers reported more favorable attitudes towards the association of luxury with sustainability rather than the association of fast fashion with sustainability. This illustrates that luxury can simultaneously be perceived as gold and green. Accordingly, Kapferer [10] contended that luxury and sustainability coincide when both focus on beauty and rarity. Janssen et al. [4] showed that product scarcity and durability increased the perceived luxury–sustainability fit. Similarly, Kapferer and Michaut-Denizeau [15] highlighted that consumers found less contradiction between the two concepts when luxury was defined in terms of superior quality.

A very small number of studies have explored the role that value perceptions play in motivating consumers to buy sustainable luxury (summarized in Table 1). For example, Cervellon and Shammas [2] showed that several value perceptions of luxury (e.g., conspicuousness, belonging, hedonism, and durable quality) are enhanced through sustainable luxury. Ki and Kim [5] found that intrinsic values (social consciousness and seeking personal style) play a critical role in sustainable luxury consumption, which focuses on timeless style, durability, and quality. More recently, Wang et al. [6], in their cross-cultural study, reported that hedonic needs increased the likelihood of consumers in the UK and China purchasing sustainable luxury. They also found that social values such as the need for conformity and exclusivity in sustainable luxury products had contrasting effects across the UK and China. Their research provides preliminary insights, and our research extends their work by rigorously examining the influence of five key luxury values on sustainable luxury purchase behaviors.

Table 1.

Past research examining the impact of values on sustainable luxury consumption.

2.3. Luxury Value Perceptions

Due to the subjective and multidimensional nature of luxury, it is often defined and measured in terms of a wide variety of value perceptions [46]. According to Smith and Colgate [47], consumer value is one of the key approaches and widely used concepts to better understand and predict consumer behavior. Earlier research on perceived values mainly focused on price and quality issues, failing to come to a consensus upon a unified conceptualization and operationalization of the construct [48]. However, a common thread that runs through the various definitions is the degree to which a product is able to satisfy consumer needs and wants [49]. By integrating personal and interpersonal effects, Vigneron and Johnson [20,35] developed a conceptual framework of luxury-seeking consumer behavior. They posited that the decision-making process of purchasing luxury products can be explained by five luxury values and corresponding motivations: conspicuous (Veblenian), unique (snob), social (bandwagon), emotional (hedonist), and quality values (perfectionist motivations).

For many significant studies on consumer value perceptions of luxury, this framework has served as a foundation. For instance, Wiedmann et al. [50] extended this framework for a customer segmentation purpose by integrating four latent value dimensions: individual (i.e., self-identity, hedonic, and materialistic), social (i.e., prestige and conspicuous), financial (i.e., price), and functional (i.e., uniqueness, quality, and usability). Similarly, Shukla [51] classified luxury value perceptions as personal (i.e., hedonism, materialism), social (i.e., status and conspicuous), and functional (i.e., price-quality and uniqueness). However, these studies have suggested further empirical testing of consumers’ perceived values to corroborate the existing theory related to luxury purchasing behaviors [6,50,51,52,53]. Drawing on the luxury-seeking consumer behavior framework, we argue that if these values are sufficient to motivate consumers to purchase luxury products that highlight their sustainable features and practices, it will be evident that sustainability and luxury are indeed compatible.

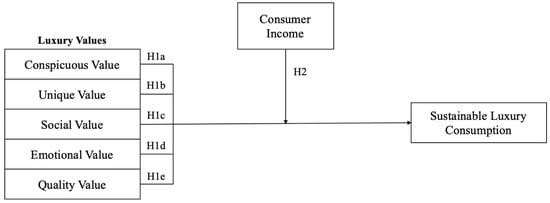

2.4. Consumer Income

Consumer income is one of the important factors that can explain the consumption rate of luxury products [34]. In economics, luxury is conceptualized in terms of consumer income, wherein a greater proportion is spent on luxury goods as a result of an increase in income [54]. Indeed, researchers have attributed the steady growth of the luxury market (apart from the decline during the recession and COVID-19 pandemic) to a growing ratio of people with high income [35]. Further, previous studies have reported that not only consumers with high income purchase luxury goods, but also consumers with low income [55,56]. This is due to the democratization of luxury, whereby luxury brands have launched new product lines, product extensions, or new brands that are more affordable and accessible to reach new consumers [35,57]. Once a domain reserved to the elites, the democratization of luxury has rendered luxury goods accessible to low- and middle-income consumers. However, the rate of luxury purchases tends to be higher when income is higher [34,58,59]. In other words, high-income individuals tend to be heavy luxury consumers. Although there has been some research on the influences of consumer income on value perceptions towards luxury products, there have not been any, to the best of our knowledge, about luxury products with sustainable features. Therefore, the role of consumer income in the relationship between luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption is examined in this study. Figure 1 depicts the proposed research model.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Relationship between Luxury Value Perceptions and Sustainable Luxury Consumption

The conspicuous value of luxury goods, driven by the Veblen effect, reflects consumers’ need to signal their wealth and status to others [35,60,61]. Therefore, luxury brands are linked with feeding one’s ego and status [2], whereby conspicuous goods primarily satisfy prestige needs [62,63]. These values nonetheless are not in alignment with sustainability [9]. Additionally, Beckham and Voyer [64] argued that sustainable luxury goods do not reflect high status, social power, and prestige. In contrast, Griskevicius et al. [65] posited that altruism can function as a “costly signal” associated with status and prestige. In an experimental study, the authors found that status motives increased consumers’ desire for green products in public settings (but not private) and when luxurious green products cost more (but not less) than non-green but more luxurious products. This way, consumers can communicate that they are a pro-social rather than a pro-self individual. In other words, “going green to be seen.” Cervellon and Shammas [2] also supported the idea that sustainable luxury products have a conspicuous value wherein consumers can show off that they care about the environment. Similarly, Johnson et al. [66] found that the need for status significantly motived the conspicuous consumption of pro-social products, and that fear of negative evaluation significantly moderated this relationship. As a result, conspicuous consumption has become a new form of demonstrating pro-environmental and pro-social behaviors. These consumers mainly favor sustainable practices in public contexts to make a good impression on others and confirm a social status of an environmentally conscious consumer. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H1a:

Conspicuous value will have a positive influence on sustainable luxury consumption.

The unique value refers to consumers’ value related to conveying one’s identity and differentiating oneself from others [67]. Due to their limited distribution and premium price, luxury products can be used as a means of expressing uniqueness [50,68]. Uniqueness represents exclusivity and differentiation [9], which makes the product more expensive, of higher quality, and longer-lasting compared to the mass-produced fast fashion, which is much cheaper, easily disposable, and unsustainable. Although Torelli et al. [69] posited that perceived exclusivity decreases as the sustainability features of luxury products are highlighted, several studies suggest the contrary. For instance, a field experiment by Janssen et al. [4] revealed that product exclusivity increased the perceived luxury–corporate social responsibility fit, resulting in more favorable consumer attitudes towards such products. In a similar vein, Park et al. [70] found that perceived exclusivity for sustainable luxury products had a significant positive moderating effect on the relationship between attitude and willingness to pay for the product. Further, in their cross-cultural study, Wang et al. [6] found that the need for exclusivity had a significant positive impact on sustainable luxury purchase intentions in the UK, but a negative impact in China. Ki and Kim [5] found that seeking personal style, which reflects consumers’ personal taste over mainstream and popular items, is a significant driver of sustainable luxury consumption. As a result, snob-motivated consumers may be driven to buy sustainable luxury. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H1b:

Unique value will have a positive influence on sustainable luxury consumption.

Regarding social value, consumers’ purchase of luxury brands is linked to the quest to be perceived well in society, be accepted by others, and leave a good impression [71,72]. Driven by the desire to enhance one’s self-concept and self-worth in society, social value facilitates group affilation [20,50,73,74]. By integrating the symbolic meaning of luxury brands into their identity, bandwagon-driven consumers emulate the behavior of their prefered reference group to be identified as memebers of the group. Given that consumers have become more aware about environmental and social issues despite their social class, consumption has shifted from “conspicuous” to “conscientious” [3,7,43]. Sustainable luxury consumption promises both utilities. Herein, the purchase of sustainable luxury can signal status and prestige [65], as well as provide an opportunity for an elite experience derived from buying items produced in a responsible manner [7]. Additionally, Wang et al. [6] showed that the need for conformity in Chinese consumers was positively associated with greater purchase intentions towards sustainable luxury products. However, in an individualistic society such as the UK, they found that the relationship was negatively significant. Considering that the current study is conducted among a collective society (i.e., Qatar), the relationship is expected to be positive. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H1c:

Social value will have a positive influence on sustainable luxury consumption.

With regards to emotional value, hedonic-motivated consumers purchase luxury products for their emotional value, which refers to the desire to experience personal rewards and fulfillment through consumption. Such emotional responses are associated with sensory pleasure and aesthetic beauty [35,50,75,76], as well as guilt [6], making luxury consumption a double-edged sword. Specifically, luxury consumers experience positive emotions when making a purchase [54], but experience negative emotions afterwards [6]. Certainly, Cervellon and Shammas [2] found that Italian and French consumers felt more guilt after buying expensive products or wearing fur coats. Wang et al. [6] nonethless argued that the sustainability aspect of some luxury items may aid in achieving a guilt-free pleasure, and that hedonic needs were a significant driver of purchase intentions towards sustainable luxury products. By measuring actual sustainable luxury consumption behavior, other scholars have found an inverse relationship, wherein sustainable luxury products lessened the consumers’ feeling of pleasure [2]. This is plausible due to the diminishing hedonic utility derived as consumers move from luxury consumption to sustainable luxury consumption [2]. The authors argue that there is a paradox in the relationship of emotional value with luxury consumption and sustainable luxury consumption, wherein emotional value drives up luxury consumption (i.e., positive association) and drives down (or diminishes) sustainable luxury consumption. In line with Cervellon and Shammas’ [2] argument regarding the inverse relationship between emotional value and sustainable luxury consumption, we hypothesize that:

H1d:

Emotional value will have a negative influence on sustainable luxury consumption.

The quality value is another important motivator for luxury consumers. Quality represents functionality and what a product actually does, rather than what it represents [77,78]. The literature on luxury consumption views and emphasizes characteristics related to superior quality, durability, timelessness, craftsmanship, reassurance, and performance as fundamental in luxury products [52,75,79]. Therefore, luxury is the ideal foundation for products that preserve essential environmental and social values [9]. However, a number of studies [17,19,70] reported that consumers perceive luxury items made from recycled materials negatively and as being of lower quality. Contrary to these findings, Grazzini et al. [44] found that incorporating recycled materials into luxury products led to greater purchase intentions. Similarly, Dekhili et al. [19] reported that when social information was mentioned, consumers associated significantly lower quality with negative CSR luxury brand image. There is also evidence that luxury products that are durable and of exceptional quality increase the perceived luxury–sustainability fit [4,15]. For example, Cervellon and Shammas [2] showed that values related to durable quality were significantly enhanced through sustainable luxury. Hence, we hypothesize that:

H1e:

Quality value will have a positive influence on sustainable luxury consumption.

3.2. The Moderating Role of Consumer Income

Once a domain reserved for the elites, the democratization of luxury has rendered luxury goods accessible to low- and middle-income consumers, even if only occasionally [35,57]. The consumption rate of luxury products nevertheless tends to be higher when income is higher as those individuals can afford to buy high-priced goods [34,58,59]. With regards to luxury products with sustainable features, researchers repeatedly highlighted that only a few consumers consider sustainability when purchasing luxury [9,14,18,32,33]. Two main factors that explain this are the fact that consumers assume luxury items to be devoid of sustainability and ethical issues due to their high prices and that they purchase too few luxury items (compared to fast fashion) to consider their environmental and social impact [18,33]. Considering that high-income individuals are heavy luxury consumers and low/middle-income individuals are light luxury consumers [34,58,59], it can be assumed that high-income consumers are more likely to consider sustainability when purchasing luxury and thereby purchase items with sustainable attributes. Therefore, consumer income is likely to strengthen the relationship between luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption. There is also compelling evidence that supports the predictive power of consumer income as a moderating variable with regards to consumer behavior [80,81,82,83]. In line with this, we hypothesize that:

H2:

Consumer income will significantly moderate the relationship between luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption, namely: (a) conspicuous value, (b) unique value, (c) social value, (d) emotional value, and (e) quality value.

3.3. Discriminating between Heavy and Light Sustainable Luxury Consumers

Behavioral characteristics of sustainable luxury consumers are very useful perspectives and help in gaining a deeper understanding of consumer behavior in general, consumption patterns, consumer values, and value segmentation. For example, consumer studies have categorized consumers as light, medium, and heavy users based on their usage behaviors [21,22]. Thereby, providing a deeper understanding of heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers and their values through psychographic and behavioral angles can help in understanding consumption patterns and developing effective marketing strategies. Considering that luxury values are often associated with sustainable luxury consumption [2,6], heavy sustainable luxury consumers are likely to differ from light sustainable luxury consumers based on their perceived luxury values, namely conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values. As a result, it is important to identify which luxury value dimensions most discriminate between heavy and light consumers of sustainable luxury. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H3:

Luxury values will significantly discriminate between heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers, namely: (a) conspicuous value, (b) unique value, (c) social value, (d) emotional value, and (e) quality value.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Measurement and Questionnaire Design

A quantitative approach was implemented in the current study to examine the hypothesized relationships. To measure the underlying value dimensions of consumers’ sustainable luxury purchase behaviors, we adapted measurement items from the literature (Table 2). The survey consisted of four sections, containing questions about consumers’ consumption behaviors for luxury goods (i.e., type of product and brand, and consumption level), their luxury value perceptions, sustainable luxury purchasing behaviors, and their demographic information. The first section of the questionnaire begins with a definition of luxury fashion items, which is “luxury items are defined, for the purpose of this study, as designer items that are characterized by their symbolic meaning, beauty, quality, rarity, and price” [84]. To target actual consumers of luxury fashion goods, a filter question “have you purchased luxury fashion items in the past two years?” was used. Participants who indicated that they have not bought luxury products within the past two years, regardless of whether they were sustainable or not, were excluded from the study. Participants were then asked to identify the types of luxury product that they mostly buy, which were: clothing, footwear, handbags, jewelry, watches, and accessories (e.g., sunglasses, hats, wallets, belts, scarves, ties).

Table 2.

Measurement items.

To distinguish between the degree of luxury associated with brands consumers mostly purchase from, brands were classified into three categories: inaccessible, intermediate, and accessible brands [85]. Intermediate and inaccessible luxury brands include Chanel, Cartier, Rolex, Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Givenchy, Alexander Wang, Stella McCartney, and Versace, while accessible luxury brands include Polo Ralph Lauren, Hugo Boss, Coach, and Calvin Klein. In general, consumers who have acquired luxury products within the past two years are characterized as luxury consumers [84]. However, the emergence of accessible luxury products has made it difficult to differentiate between non-luxury and luxury consumers alone as luxury consumers fall along a spectrum of occasional to daily luxury consumption. Heine [84] identified three segments of luxury consumers based on their level of luxury consumption: light, regular, and heavy consumers of luxury. Light luxury consumers occasionally purchase accessible luxury goods; regular luxury consumers frequently purchase accessible, intermediate, and sometimes inaccessible luxury goods; and heavy luxury consumers extensively purchase accessible, intermediate, and inaccessible luxury products. Thus, participants were asked to indicate their luxury products consumption level.

The second section of the questionnaire measured respondents’ perceptions of luxury values. The scale contained conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values, which consisted of 17 items that were adapted from different studies found in Lee et al.’s [71] study: conspicuous value had four items [51]; unique value was measured with three items adapted from Wiedmann et al. [50]; social value contained four items [72]; emotional value contained three items [50]; and lastly quality value was measured with three items [35].

The third section asked respondents about their sustainable luxury consumption, wherein the scale had three items taken from Ki and Kim [5]. Further, luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Lastly, the fourth section of the questionnaire inquired about the respondents’ demographics, which included gender, nationality, age, highest level of educational, and monthly income. Moreover, this survey was composed of 29 items in total and was ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University.

4.2. Sampling and Data Collection

A self-administered online survey was used to collect data. The questionnaire was distributed electronically using the convenience sampling technique, targeting only luxury consumers in Qatar. Accordingly, the survey invitations were distributed via email to a list of graduate students at Qatar University as well as social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. The survey included a consent form that participants had to agree to before proceeding to the questionnaire. Over a two-month period, starting mid-January 2022, a total of 383 responses were gathered. However, 35 responses were removed as the respondents had not purchased a luxury item within the recent two years, resulting in a total of 348 valid responses. According to Hair et al. [86], the ratio of at least 20:1 determines the adequacy of the sample size for multiple regression analysis, meaning 20 observations per variable. The present study had eight variables, which equated to 160 necessary observations. Hence, the 348 responses are more than enough for the nature of this study.

4.3. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using SPSS software. For the purposes of the present study, the following analysis techniques were applied: descriptive, reliability, hierarchical multiple regression, and discriminant analyses. Descriptive analysis was used to understand characteristics of the sample, while reliability analysis was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the variables. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was employed to test the conceptual model and hypotheses under investigation. Multiple regression, a multivariate analysis technique, explains the effect of multiple predictor variables on one outcome variable, while hierarchical multiple regression examines this effect in a sequential manner. Consequently, regression analysis goes beyond mere association to predict one variable from another and/or to demonstrate the effect of one or more variables on another [87].

In line with this, we first examined the direct effect of luxury values on sustainable luxury consumption using multiple regression. After that, the moderating effect of consumer income in the relationship between the five luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption was examined using hierarchical regression. Following Jaccard et al. [88] and Ndubisi [89], a three-tier multiple regression was utilized.

Lastly, the stepwise discriminant analysis is an efficient and logical method of selecting the most discriminating variable [90,91]. As such, the stepwise discriminant analysis of sustainable luxury consumers was conducted to discriminate between heavy consumers of sustainable luxury and light consumers of sustainable luxury. Consumers were classified into heavy and light groups based on the median value of the dependent variable (sustainable luxury consumption), wherein values above 4.00 were used to classify heavy sustainable luxury consumers and values below 4.00 were used to classify light sustainable luxury consumers. By using group centroids to compare between heavy and light consumers, discriminant analysis has the advantage of considering the interactions between each variable, as opposed to the t-test [91].

5. Results

5.1. Profiles of the Respondents

The demographic profiles of the respondents (i.e., gender, nationality, age, highest level of education, and monthly income) are summarized in Table 3. Among the respondents, 59.2% were female and 40.8% were male. With regards to the nationality of respondents, 64.7% were Qatari and 35.3% were non-Qatari. Past studies have shown that race and gender have key implications for conspicuous consumption and purchase intention in relation to luxury products [80,92]. Further, the age groups were distributed as follows: 18–24 years (19%), 25–34 years (52.6%), 35–44 (20.7%), 45–54 (5.5%), and over 55 years (2.3%). Moreover, most of the participants held a bachelor’s degree (59.2%), followed by those who held a postgraduate degree (32.2%), and those who had a high school degree (8.6%). In terms of monthly income, 24.4% of the respondents earned less than QAR 18,000, 40.2% earned between QAR 18,001 and QAR 36,000, 24.1% earned between QAR 36,001 and QAR 54,000, 6% earned between QAR 54,001 and QAR 72,000, 3.4% earned between QAR 72,001 and QAR 91,000, and 1.7% earned more than QAR 91,001.

Table 3.

Characteristics of respondents.

The respondents included in the analysis (348) had all purchased luxury products within the past two years. According to Heine [84], consumers who have acquired luxury products within the past two years are characterized as luxury consumers. Therefore, participants who indicated that they had not bought luxury products within the past two years, regardless of whether they were sustainable or not, were excluded from the study. Participants were then asked to identify the types of luxury product that they mostly buy, which were: clothing, footwear, handbags, jewelry, watches, and accessories (e.g., sunglasses, hats, wallets, belts, scarves, ties). They were also asked to indicate the type of luxury brand they have purchased from, as well as their level of luxury consumption. Table 4 presents respondents’ luxury consumption habits.

Table 4.

Luxury consumption habits.

Respondents had purchased almost equal amounts of clothing, footwear, bags, and accessories items, specifically 19.2%, 17.8%, 19.5%, and 18.8%, respectively. However, jewelry and watches were purchased less, 12.5% and 11.8%, respectively. With regards to brand category, more than half of the respondents had mostly purchased from inaccessible brands (62.9%), followed by accessible brands (22.7%) and intermediate brands (14.4%).

The emergence of accessible luxury products has made it difficult to differentiate between non-luxury and luxury consumers alone as luxury consumers fall along a spectrum of occasional to daily luxury consumption. Heine [84] identified three segments of luxury consumers based on their level of luxury consumption: light, regular, and heavy consumers of luxury. Light luxury consumers occasionally purchase accessible luxury goods; regular luxury consumers frequently purchase accessible, intermediate, and sometimes inaccessible luxury goods; and heavy luxury consumers extensively purchase accessible, intermediate, and inaccessible luxury products. In the current sample, 42% of the respondents were light luxury consumers, 42.5% were regular luxury consumers, and 15.5% were heavy luxury consumers.

5.2. Reliability Analysis

Prior to testing the proposed model and hypotheses in the current study, the reliability of the measurement scales was evaluated. The most widely used measure of internal consistency is the Cronbach’s alpha (coefficient α), whereby reliability is confirmed when Cronbach’s α value is 0.7 or higher for all the examined constructs [89,93]. The results of the reliability analysis, summarized in Table 5, show that the Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.78 to 0.87, exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.7 in all instances. Therefore, all measures have acceptable or high reliability, confirming internal consistency.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics and reliability estimates of the measured constructs.

5.3. Direct Effects

The direct effects of the five luxury values on sustainable luxury consumption were tested. The results summarized in Table 6 suggest that approximately 48.5% of the variations in sustainable luxury consumption are explained by the five values of luxury (i.e., conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values; F = 61.942; p-value < 0.001).

Table 6.

Association of luxury values with sustainable luxury consumption.

As seen in Table 6, the results further indicate that all five variables are significant at a 5% significance level. These variables are conspicuous value (β = 0.149; p = 0.011), unique value (β = 0.424; p < 0.001), social value (β = 0.182; p < 0.001), emotional value (β = −0.275; p < 0.001), and quality value (β = 0.350; p < 0.001). The positive coefficients indicate positive influences, whereby the dependent variable increases as the independent variable increases. In contrast, the negative coefficients indicate negative influences, whereby the dependent variable decreases as the independent variable increases. Specifically, conspicuous, unique, social, and quality values have a significant positive relationship with sustainable luxury consumption, while emotional value has a significant inverse relationship with sustainable luxury consumption. Therefore, the results firmly support all elements of hypothesis H1 (i.e., H1a, H1b, H1c, H1d, and H1e). Further, unique value emerged with the highest β value, indicating that it is the most important determinant of sustainable luxury consumption.

5.4. Moderating Effects

The moderating effect of consumer income in the relationship between luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption is examined in Table 7. Monthly income was first recoded into two categories: mid-low income (below QAR 18,000–36,000) and mid-high income (QAR 36,001–91,000). A hierarchical multiple regression was conducted by entering the five predictor variables (i.e., luxury values) in model 1, the moderating variable (i.e., monthly income) in model 2, and the interaction terms (i.e., the product of the predictor and moderating variables) in model 3. The model 3 results summarized in Table 7 indicate that the predictor and moderating variables contribute significantly (F = 27.637; p-value < 0.001) and predict approximately 48% of the variations in sustainable luxury consumption. However, at a 5% significance level, consumer income moderates only one of the relationships between luxury values and sustainable luxury consumption, providing partial support for hypothesis H2. Precisely, consumer income moderates the relationship between unique value (β = 0.395; p = 0.050) and sustainable luxury consumption. Thus, the results firmly support H2b, but reject H2a, H2c, H2d, and H2e. This significant outcome for unique value (H2b) makes sense since consumers are generally more willing to pay a premium price for products they deem unique; a willingness that increases with the ability to pay, which generally characterizes higher income consumers. This tendency is not necessarily so for the other value perceptions. Charles et al. [80] argued that status products surface in unique categories in which greater expenditures are generally associated with higher income.

Table 7.

Moderating Effects of Consumer Income.

5.5. Discriminant Analysis

The stepwise discriminant analysis of sustainable luxury consumers was conducted to identify which value dimensions most discriminate between heavy and light consumers of sustainable luxury. According to Klecka [80], the structure correlation, as opposed to the standardized coefficient, is generally regarded as more accurate in predicting each variable’s relative discriminant power, considering that the variables could be correlated [91]. The loadings of ±0.30 were used to identify the significant discriminating variables as any variable exhibiting a loading of ±0.30 or higher is generally considered substantive [91].

The five luxury values were introduced to discriminate between heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers, namely conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values. Based on the structure correlation, Table 8 shows that all five luxury values are sufficient for discriminating between heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers. The results reveal that all five variables have structure correlation higher than ±0.30. Specifically, the variables are ranked in the following order based on their structure correlation: quality value (0.78), unique value (0.73), social value (0.54), conspicuous value (0.37), and emotional value (0.31). Thus, all five luxury values discriminate between heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers, firmly supporting hypothesis H3.

Table 8.

Luxury Values Structure Correlations and Mean Values.

Table 8 also reveals the mean ratings for heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers. There is a considerable difference between the mean values of heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers on all five values, in favor of the heavy sustainable luxury consumers. Therefore, heavy sustainable luxury consumers differ from light sustainable luxury consumers based on their perceived luxury values, namely conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This research explored the role of luxury values and consumer income on sustainable luxury consumption in Qatar. Grounded in the luxury-seeking consumer behavior model [20], the study examined the direct effect of luxury values on sustainable luxury consumption, and the moderating effects of consumer income in the said relationship. Additionally, the study identified which value dimensions discriminate between heavy and light consumers of sustainable luxury.

We found that conspicuous, unique, social, and quality values motivate consumers to purchase sustainable luxury products, but the emotional value demotivates consumers to do so. In collective societies, consumers are more susceptible to interpersonal influences [94]. Therefore, these individuals place more importance on one’s value related to wealth and status, differentiation from others, and social groups.

Previous studies suggest that the conspicuousness of sustainable luxury goods can help consumers demonstrate that they care about the environment and confirm a social status of a responsible consumer [2,65]. The results of the current research are in alignment with these studies. Further, Wang et al. [6] found that the need for conformity had a positive impact on sustainable luxury purchase intentions in Chinese consumers, while the need for exclusivity had a negative impact. However, other studies found that consumers seeking uniqueness look towards sustainable luxury products as they can be perceived as exclusive and different from other luxury products [4,5,95]. The results of this study reveal that people consume luxury products with sustainable features to improve the way they are perceived by others in society as well as differentiate themselves. Thus, the findings provide further evidence that interpersonal value perceptions are significant drivers of sustainable luxury consumption.

As for personal value perceptions, we found that luxury products with sustainable features lessened consumers’ feeling of pleasure. This confirms that this relationship is indeed paradoxical [2]. Luxury consumption entails a psychological cost such as guilt, thereby the incorporation of sustainable practices is expected to alleviate such negative emotions [6]. For instance, Cervellon and Shammas [2] found that sustainable luxury consumption led to guilt-free pleasure, but simultaneously decreased the hedonic value. Therefore, although consumers could feel less guilt after purchasing sustainable luxury, they do not necessarily feel more pleasure. Further, Steinhart et al. [96] pivoted that consumer tend to perceive luxury as hedonic and sustainability as utilitarian. The findings of our study further strengthen such an explanation. Moreover, the durable quality of luxury products is enhanced through sustainable practices, leading consumers to perceive a better fit between sustainability and luxury [2,4,15]. Although earlier studies found that the use of recycled materials was perceived negatively and as being of lower quality [17], recent studies found the contrary [19,44], suggesting that luxury consumers’ value perceptions are evolving and changing. Indeed, our results corroborate these findings.

The results also revealed that heavy consumers of sustainable luxury, more so than light consumers, have higher value perceptions towards sustainable luxury products. Heavy sustainable luxury consumers differ from light sustainable luxury consumers mostly on the quality value they find in such products, followed by the unique, social, conspicuous, and lastly emotional values. Hence, consumers with higher perceptions of luxury values are more likely to be heavy consumers of sustainable luxury.

Regarding the moderating effects of consumer income, the results of the regression analysis reveal mixed results. For example, consumer income significantly moderates the relationship between unique value and sustainable luxury consumption. This suggests that consumers with high incomes purchase sustainable luxury products to differentiate themselves from others, wherein these consumers can afford to buy expensive luxury products with sustainable features to feel unique. Consumers’ values related to status, social approval, pleasure, and quality may equally motivate consumers with both high and low incomes to purchase sustainable luxury.

6.1. Implications

Theoretically, this study enriches the extant literature on the relatively new concept of sustainable luxury. Researchers have paid little attention to understanding the sustainability-related motives of luxury consumers, and how and why they engage in sustainable consumption, as the debate has been mostly on whether sustainability can even be compatible with luxury [9]. Although a recent study by Wang et al. [6], tried to shed some light on the impact of luxury value perceptions on luxury products with sustainable features, it only focused on three value dimensions (e.g., exclusivity, conformity, and hedonism needs), ignoring other value dimensions. As such, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first empirical study to incorporate all five commonly held luxury values (i.e., conspicuous, unique, social, emotional, and quality values) and measure their influence on sustainable luxury purchase behaviors. Further, by examining the moderating role of consumer income, a more advanced understanding of sustainable luxury can be gained. Hence, this research offers significant contributions to the literature and advances the existing knowledge of consumer value perceptions related to purchasing behavior of sustainable luxury. It also deepens scholarly understanding of the compatibility between sustainability and luxury, and answers calls for further empirical testing of luxury value perception [46,51,52]. As a result of the current research, a thorough empirical testing of perceived values contributed to the reliability of the existing literature and theories regarding luxury purchasing behaviors. Additionally, the study contributes and advances the luxury-seeking consumer behavior model [20] with regards to luxury products with sustainable features.

The study also enriches the limited literature on sustainability and luxury in the context of an emerging Middle Eastern market. With increasing globalization, it is imperative to explore research across different markets as a single brand can reflect different meanings and values for different nationalities. There are differences in not only culture but also in consumers’ perceptions of brands. Accordingly, researchers have highlighted the differences in luxury consumption among developed and emerging markets [6,19,51,77]. However, research on luxury consumption has been mostly restricted to Western countries, with a paucity of studies in Eastern countries, particularly Middle Eastern countries [97]. Even less studies on sustainable luxury have been conducted in emerging markets [9]. Therefore, conducting this study among a sample of Middle Eastern consumers based in a transitional economy within Qatar advances the limited body of knowledge and marketing practice in the Middle East in particular and developing countries in general.

As for the practical implications, the main utility resides specifically in its capacity to inform the development of effective strategies and tactics for acquiring new sustainable luxury consumers, and for retaining existing ones and strengthening relationships with them. Firms can also use the findings of this research to identify heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers and the specific factors that are most important in driving their purchase decisions. Thus, the results of this study provide practical insights for understanding the link between luxury and sustainability, as well as promoting sustainable luxury in emerging markets.

The study demonstrates that consumers are eager to purchase sustainable luxury. Marketers therefore have the responsibility to communicate the brand’s sustainability efforts, especially novel and unfamiliar ones, to allow consumers to make informed decisions. Considering that consumers purchase sustainable luxury to signal wealth and status, feel unique, follow social norms, and have durable products, managers could make such products more expensive, conspicuous, and exclusive. To do so, marketers could employ rarity marketing tactics, wherein such products could be limited editions or part of capsule collections. By educating consumers about sustainability and making buying sustainable luxury trendy, marketers could also create and leverage new social norms. They should also emphasize the exceptional quality of sustainable luxury products and demonstrate that such products match, if not exceed, the superior quality associated with general luxury products. Moreover, considering that consumers do not feel as much pleasure by purchasing luxury products with sustainable features, managers should focus on alleviating feelings of guilt instead.

Further, these five values discriminate between heavy and light sustainable luxury consumers. Heavy consumers of sustainable luxury, more so than light consumers of sustainable luxury, have higher perceptions of luxury values, ranked in the following order: quality, unique, social, conspicuous, and emotional values. Herein, looking at the consumer values and consumption patterns of sustainable luxury consumers can help managers with market segmentation strategies to better understand their ideal consumers and target audiences. By dividing consumers into groups based on shared psychographic and behavioral characteristics, managers can cater to specific consumer needs and create messages to communicate and reach these consumers more efficiently.

Lastly, consumer income further helps with market segmentation. The study shows that the impact of unique value on sustainable luxury consumption is statistically greater for consumers with high incomes. Hence, other than the uniqueness of the product, managers should aim to communicate more exclusive messages for high-income consumers and create more personal experiences by inviting them to private shows and giving them early access to limited edition collections.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This research has certain limitations, one of which is social desirability bias. In a survey approach, respondents could answer in line with what is perceived to be socially appropriate [98]. Selection bias may be another limitation, wherein ethical and environmentally conscious individuals are highly expected to partake in research pertaining to sustainability [6]. Additionally, the employed sampling technique in this research, convenience sampling, substantiates selection bias, whereby most of the respondents are millennials and hold a bachelor’s degree. This further limits the generalizability of the research findings. Although such biases were minimized by using a self-administered survey, posting survey invitations online, and ensuring anonymity, the results of this study must be interpreted with appropriate caution.

Another limitation of the study is that it focuses on only luxury fashion products. Therefore, other luxury product categories such as cosmetics and automobiles might yield different results. Further, the data were collected amidst a global pandemic that imposed serious repercussions on the luxury industry. Consequently, the personal luxury goods have fallen for the first time since 2009 by 23% (EUR 217 billion) during COVID-19. According to D’Arpizio et al. [99], aside from a decline during the economic recession from 2008 to 2009, the luxury sector experienced steady growth of 6% from 1996 to 2019. The luxury sector is therefore expected to recover by 2022 or early 2023 [99], indicating the resilience of the sector and relevance of the research findings.

The proposed conceptual framework in this research could benefit from further empirical testing with large, representative samples across vastly different cultures to support its validity and reliability. Further, a cross-culture study could shed some light on how culture can shape consumer behavior and allow luxury brand managers to devise unique marketing plans for each market. Integrating other moderating effects may also provide additional information and strengthen the sustainability–luxury link, such as psychographic factors, affective commitment, and religiosity. Moreover, a mixed-method approach could also provide a broader perspective on the topic, whereby elicitation techniques could draw out more meaningful and honest responses. Conducting a longitudinal study to understand changes in sustainable luxury consumption behavior over an extended period of time could also be useful.

Additionally, this research does not focus on a particular luxury brand, but rather a broader category of luxury brands. Therefore, centering future research around specific luxury brands, especially ones that are clearly oriented towards sustainability, could be beneficial. Lastly, the current research focuses only on luxury fashion products. Therefore, other luxury product categories such as cosmetics and automobiles could help in understanding how the model performs across different sectors and advance knowledge on sustainable luxury consumption behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and N.O.N.; Writing—original draft, S.A.; Writing—review and editing, N.O.N.; Supervision, N.O.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Qatar University (QU-IRB 1653-E/22; 19 January 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eastman, J.K.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Flynn, L.R. Status Consumption in Consumer Behavior: Scale Development and Validation. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 1999, 7, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervellon, M.C.; Shammas, L. The Value of Sustainable Luxury in Mature Markets: A Customer-Based Approach. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2013, 2013, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, N.; Wiedmann, K.P.; Klarmann, C.; Behrens, S. Sustainability as Part of the Luxury Essence: Delivering Value through Social and Environmental Excellence. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2013, 2013, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, C.; Vanhamme, J.; Lindgreen, A.; Lefebvre, C. The Catch-22 of Responsible Luxury: Effects of Luxury Product Characteristics on Consumers’ Perception of Fit with Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics. 2014, 119, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.W.; Kim, Y.K. Sustainable Versus Conspicuous Luxury Fashion Purchase: Applying Self-Determination Theory. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2016, 44, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Kuah, A.T.H.; Lu, Q.; Wong, C.; Thirumaran, K.; Adegbite, E.; Kendall, W. The Impact of Value Perceptions on Purchase Intention of Sustainable Luxury Brands in China and the UK. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J.; Kleanthous, A. Deeper Luxury; 2007. WWF. Available online: https://assets.wwf.org.uk/downloads/luxury_report.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Brundtland Report. In Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; pp. 43–44.

- Athwal, N.; Wells, V.K.; Carrigan, M.; Henninger, C.E. Sustainable Luxury Marketing: A Synthesis and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N. All That Glitters Is Not Green: The Challenge of Sustainable Luxury. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2010, 2, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.; Gupta, S.; Kim, Y.K. Style Consumption: Its Drivers and Role in Sustainable Apparel Consumption: Style Consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Sustainable Consumption. In Handbook of Sustainable Development, 2nd ed.; Atkinson, G., Dietz, S., Neumayer, E., Agarwala, M., Eds.; Handbook of Sustainable Development; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Claudio, L. Waste Couture: Environmental Impact of the Clothing Industry. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, A448–A454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast Fashion, Sustainability, and the Ethical Appeal of Luxury Brands. Fash. Theory. 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Michaut-Denizeau, A. Luxury and Sustainability: A Common Future? The Match Depends on How Consumers Define Luxury. Lux. Res. J. 2015, 1, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, T.; Ali Taha, V.; Škerháková, V.; Valentiny, T.; Fedorko, R. Luxury Products and Sustainability Issues from the Perspective of Young Italian Consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achabou, M.A.; Dekhili, S. Luxury and Sustainable Development: Is There a Match? J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.; Lee, Z.; Ahonkhai, I. Do Consumers Care About Ethical-Luxury? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 106, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhili, S.; Achabou, M.A.; Alharbi, F. Could Sustainability Improve the Promotion of Luxury Products? Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 488–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. A Review and a Conceptual Framework of Prestige-Seeking Consumer Behavior. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 1999, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, W.D.; MacInnis, D.J.; Pieters, R. Consumer Behavior; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kerin, R.A.; Hartley, S.W. Marketing; McGraw-Hill Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ndubisi, N.O.; Agarwal, J. Quality Performance of SMEs in a Developing Economy: Direct and Indirect Effects of Service Innovation and Entrepreneurial Orientation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2014, 29, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.H.; Nunes, J.C.; Dreze, X. Signaling Status with Luxury Goods: The Role of Brand Prominence. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- De Botton, A. Status Anxiety; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen, T. The Theory of the Leisure Class; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Ndubisi, N.O.; Nataraajan, R. How Young Adults Segment Respond to Trusty and Committed Marketing Relationship. Psychol. Mark. 2018, 35, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, L.S.; Bernheim, B.D. Veblen Effects in a Theory of Conspicuous Consumption. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 349–373. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. Advertising Content When Brand Choice is a Signal. J. Bus. 1990, 63, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristini, H.; Kauppinen-Räisänen, H.; Barthod-Prothade, M.; Woodside, A. Toward a General Theory of Luxury: Advancing from Workbench Definitions and Theoretical Transformations. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 70, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortelmans, D. Sign Values in Processes of Distinction: The Concept of Luxury. Semiotica 2005, 2005, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Michaut-Denizeau, A. Is Luxury Compatible with Sustainability? Luxury Consumers’ Viewpoint. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Michaut-Denizeau, A. Are Millennials Really More Sensitive to Sustainable Luxury? A Cross-Generational International Comparison of Sustainability Consciousness When Buying Luxury. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Bastien, V. The Luxury Strategy: Break the Rules of Marketing to Build Luxury Brands; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. Measuring Perceptions of Brand Luxury. J. Brand Manag. 2004, 11, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anido Freire, N.; Loussaïef, L. When Advertising Highlights the Binomial Identity Values of Luxury and CSR Principles: The Examples of Louis Vuitton and Hermès. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Seo, Y.; Ko, E. Staging Luxury Experiences for Understanding Sustainable Fashion Consumption: A Balance Theory Application. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 74, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macchion, L.; Da Giau, A.; Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Danese, P.; Rinaldi, R.; Vinelli, A. Strategic Approaches to Sustainability in Fashion Supply Chain Management. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, C.; Fiorani, G.; Mariani, S. Cause Related Marketing: Armani Initiative ‘Acqua for Life’. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2014, 11, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardetti, M.A.; Torres, A.L. Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Luxury: The Ainy Savoirs des Peuple Case. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2013, 52, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, K.; Irwin, J. Willful Ignorance in the Request of Product Attribute Information. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.; Sen, S. Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why, and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvijanovich, M. Sustainable Luxury: Oxymoron? Lausanne, 2011, YUMPU. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/1150320/lecture-in-luxury-and-sustainability-sustainable-luxury-oxymoron- (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Grazzini, L.; Acuti, D.; Aiello, G. Solving the Puzzle of Sustainable Fashion Consumption: The Role of Consumers’ Implicit Attitudes and Perceived Warmth. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S. Factors Affecting Sustainable Luxury Purchase Behavior: A Conceptual Framework. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 31, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennigs, N.; Wiedmann, K.P.; Klarmann, C.; Strehlau, S.; Godey, B.; Pederzoli, D.; Neulinger, A.; Dave, K.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; et al. What Is the Value of Luxury? A Cross-Cultural Consumer Perspective. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 1018–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.B.; Colgate, M. Customer Value Creation: A Practical Framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2007, 15, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Darden, W.R.; Griffin, M. Work and/or Fun: Measuring Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Value. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 20, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y. Key Service Drivers for High-Tech Service Brand Equity: The Mediating Role of Overall Service Quality and Perceived Value. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.P.; Hennigs, N.; Siebels, A. Value-Based Segmentation of Luxury Consumption Behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P. The Influence of Value Perceptions on Luxury Purchase Intentions in Developed and Emerging Markets. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 574–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, C.; Mckechnie, S.; Chhuon, C. Co-Creating Value for Luxury Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, K.P.; Hennigs, N.; Siebels, A. Measuring Consumers’ Luxury Value Perception: A Cross-Cultural Framework. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2007, 2007, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, J.; Renand, F. The Marketing of Luxury Goods: An Exploratory Study—Three Conceptual Dimensions. Mark. Rev. 2003, 3, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francese, P. Older and Wealthier. Am. Demogr. 2002, 20, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Twitchell, J.B. Living It Up: Our Love Affair with Luxury; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, Y.; Simmons, G.; McColl, R.; Kitchen, P.J. Status and Conspicuousness—Are They Related? Strategic Marketing Implications for Luxury Brands. J. Strateg. Mark. 2008, 16, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Duquesne, P. The Market for Luxury Goods: Income versus Culture. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, S. Luxury and Wealth. Int. Econ. Rev. 2006, 47, 495–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R. Modelling the Demand for Status Goods. ACR Spec. Vol. 1992, SV-08, 88–95. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/12198/volumes/sv08/SV- (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Veblen, T. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P. Conspicuous Consumption among Middle Age Consumers: Psychological and Brand Antecedents. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckham, D.; Voyer, B.G. Can Sustainability Be Luxurious? A Mixed-Method Investigation of Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Towards Sustainable Luxury Consumption. Adv. Consum. Res. 2014, 42, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going Green to Be Seen: Status, Reputation, and Conspicuous Conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Tariq, A.; Baker, T.L. From gucci to green bags: Conspicuous consumption as a signal for pro-social behavior. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2018, 26, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.T.; Bearden, W.O.; Hunter, G.L. Consumers’ Need for Uniqueness: Scale Development and Validation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Paul, J. Mass Prestige Value and Competition between American versus Asian Laptop Brands in an Emerging Market—Theory and Evidence. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, C.; Monga, A.; Kaikati, A. Doing Poorly by Doing Good: Corporate Social Responsibility and Brand Concepts. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 38, 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Eom, H.J.; Spence, C. The Effect of Perceived Scarcity on Strengthening the Attitude–Behavior Relation for Sustainable Luxury Products. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jang, Y.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H.-M.; Ham, S. Consumers’ Prestige-Seeking Behavior in Premium Food Markets: Application of the Theory of the Leisure Class. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seegebarth, B.; Behrens, S.H.; Klarmann, C.; Hennigs, N.; Scribner, L.L. Customer Value Perception of Organic Food: Cultural Differences and Cross-National Segments. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastanakis, M.N.; Balabanis, G. Explaining Variation in Conspicuous Luxury Consumption: An Individual Differences’ Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2147–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, L.; Tzemou, E.; Fastoso, F. Seeking Attention versus Seeking Approval: How Conspicuous Consumption Differs between Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissists. Psychol. Mark. 2020, 37, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N.; Laurent, G. Where Do Consumers Think Luxury Begins? A Study of Perceived Minimum Price for 21 Luxury Goods in 7 Countries. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.; Newman, B.; Gross, B. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, P.; Pitt, L.; Parent, M.; Berthon, J.P. Aesthetics and Ephemerality: Observing and Preserving the Luxury Brand. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2009, 52, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.; Purani, K. Comparing the Importance of Luxury Value Perceptions in Cross-National Contexts. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H.J.; Moon, H.; Kim, H.; Yoon, N. Luxury Customer Value. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 16, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, K.K.; Hurst, E.; Roussanov, N.L. Conspicuous Consumption and Race. Q. J. Econ. 2009, 124, 425–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Das, M. Uniqueness and Luxury: A Moderated Mediation Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiruwa, A.; Yadav, R.; Suri, P.K. Moderating Effects of Age, Income and Internet Usage on Online Brand Community (OBC)-Induced Purchase Intention. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2018, 15, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolske, K.S. More Alike than Different: Profiles of High-Income and Low-Income Rooftop Solar Adopters in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 63, 101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, K. Identification and Motivation of Participants for Luxury Consumer Surveys. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2010, 8, 132–145. [Google Scholar]