Green Customer and Supplier Integration for Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Effect of Sustainable Product Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

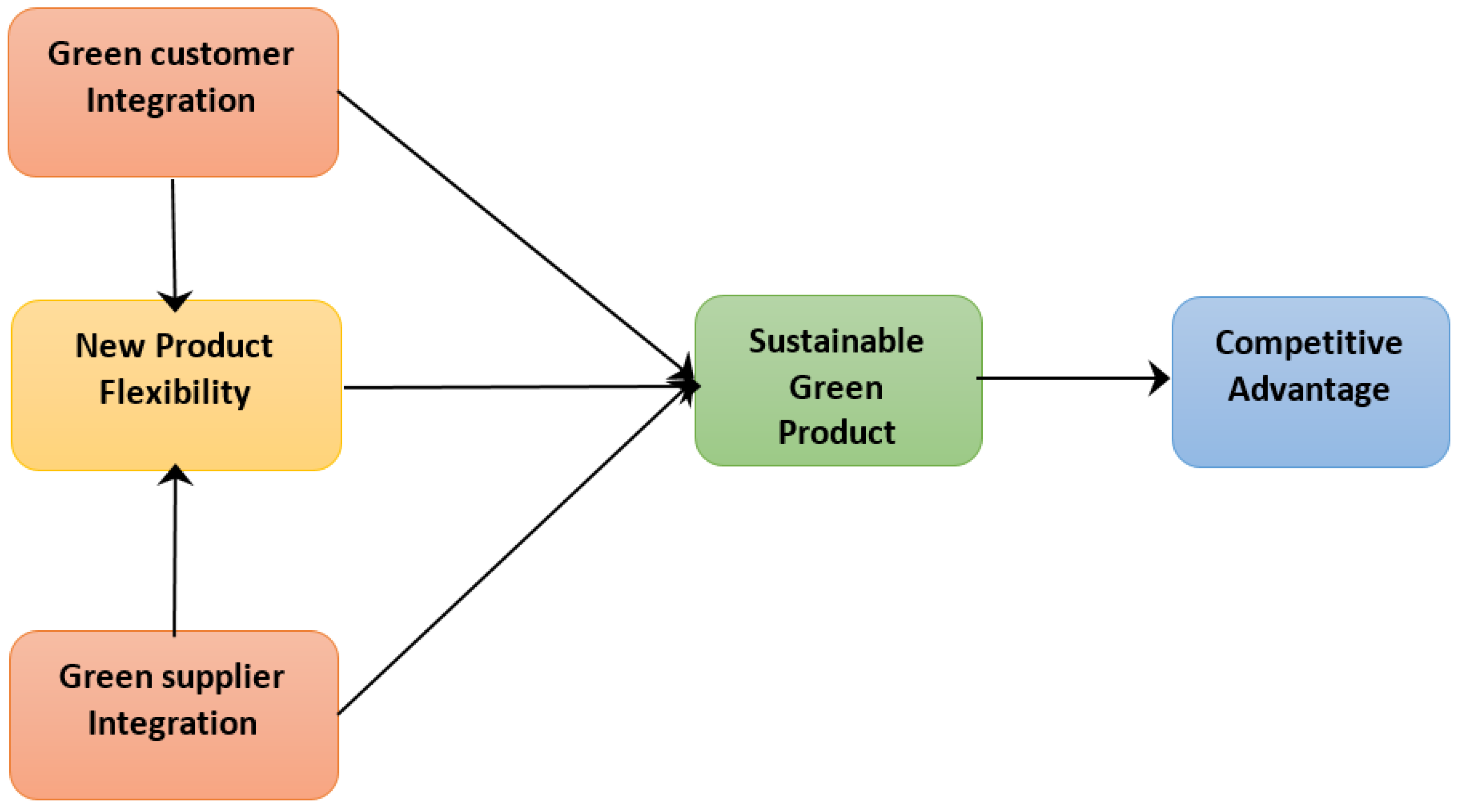

- Investigate the impact of green customer integration and green supplier integration on new product flexibility;

- Investigate the impact of new product flexibility, green customer integration, and green supplier integration on green product innovation;

- Investigate the impact of green product innovation performance on competitive advantage;

- Investigate the impact of sustainable green product innovation on the relationship between green customer integration, green supplier integration, and new product flexibility and competitive advantage.

2. Literature Review and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Green Customer Integration and New Product Flexibility

2.2. Green Supplier Integration and New Product Flexibility

2.3. New Product Flexibility and Sustainable Green Product Innovation

2.4. Green Customer Integration and Sustainable Green Product Innovation

2.5. Green Supplier Integration and Sustainable Green Product Innovation

- Discussing with suppliers the specifications/requirements related to the product;

- Sharing information and technology and together bearing the responsibility for making decisions related to products’ design specifications and requirement;

- The supplier charged with the whole responsibility for designing and making products/services according to the purchasing company’s specifications and requirements.

2.6. Sustainable Green Product Innovation and Competitive Advantage (CA)

2.7. Indirect (Interacting) Effects

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Problem Statement

3.2. Research Methods

3.2.1. Samples and Procedures

3.2.2. Scale Development Method

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Validity and Reliability

4.2. Measurement Model Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion and Main Results

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Main Results

5.3. Managerial Implications

- The results of data analysis reveal the following managerial implications that can benefit organizations in sustaining green product innovation and competitive advantage:

- Managers have to focus on what increases new product flexibility, which in turn improves and increases green product innovation performance. Therefore, customers value their integration in developing green products and this can increase the ability of a firm to launch new green products quickly to the target market at the right time, quality, and quantity.

- Managers should realize the critical role of green customer integration, green supplier integration, and new product development flexibility in sustaining green product innovation and improving the competitive advantage. Overall, a company’s supplier and customer integration and green new product flexibility are important drivers for both sustaining green product innovation and improving competitive advantage.

- ‘Go green’ is not a slogan for improving a firm’s reputation, but it should be viewed as the main concern for increasing the competitive advantage of the firm.

- Integrating both customers and suppliers into the creation of new green products is necessary to increase new product flexibility, which increases the ability of a firm to produce new green products efficiently and effectively.

- Green new product performance is a function of new product flexibility, green customer integration, and green supplier integration, which places a big emphasis on their contribution to the firm’s competitive advantage.

- For a firm to increase its competitive advantage, managers should be aware of the antecedents and consequences of new product flexibility, green customer integration, green supplier integration, and green product innovation.

- To increase green product innovation performance, firms are advised to integrate new product flexibility, green customer integration, and green supplier integration into the development of green products, because this ultimately will increase the firm’s competitive advantage.

- Managers should have a clear understanding of the relationship that links new product flexibility to green customer integration and green supplier integration and their integrated impact on sustainable product innovation and competitive advantage.

- The insight of the relationships among the research constructs (new product flexibility, green customer integration, green supplier integration, sustainable green product innovation, and competitive advantage) can assist managers in making better decisions and construct appropriate corporate, business, and functional strategies for effectively shaping a green culture that encourages the commitment of individuals to the philosophy of greenness and sustainability.

5.4. Limitation and Future Research

- This study has the following limitations that could represent avenues for future research:

- The present study is limited to one method of data collection (the cross-sectional survey). Therefore, the findings of this research must be treated with caution due to the limitations related to the positivistic paradigm. However, future research may apply other methods. Such case studies should investigate the impact of new product flexibility, green customer integration, and green supplier integration on both green product innovation performance and competitive advantage.

- The present study employed only one type of flexibility (new product flexibility) in predicting green product innovation performance. Therefore, the study calls for future research to investigate the impact of other flexibilities, such as market flexibility, supply chain flexibility, operations flexibility, modification flexibility, etc., on green product innovation performance.

- This research did not take into consideration the effect of the moderating and intervening variables (such as company size, industry life cycle, organizational structure, industry type, stakeholders’ interests, etc.) on the relationship between green product innovation and competitive advantage. Therefore, such variables should be addressed by future research.

- Finally, validating the findings of this study in different industries, sectors, and countries is another promising direction for future research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Male

- Female

- Less than 18 Years

- 18–25 Years

- 26–35 Years

- 36–45 Years

- Above 45 Years

- less than one year

- 1 to 5 years and 95

- more than five years

- Marketing

- Operations

- Sales

- Accounting or Finance

- Customer Service

- Distribution and Warehousing

- Information Technology

- Legal or Regulatory

- Research and Development

- supervisory/manager

- senior management

- employee

- sales and service

| Green customer integration Please indicate the extent of integration or information sharing between your organization and your major customer in the following areas (1 = not at all; 7 = extensive). | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Green supplier integration Please indicate the extent of integration or information sharing between your organization and your major suppliers in the following areas (1 = not at all; 7 = extensive). | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Sustainable Green product innovation Please circle the appropriate number to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each of the following statements that measure green product innovation in your company. The item scales are seven-point Likert type scales with 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = slightly disagree, 4 = neutral, 5 = slightly agree, 6 = agree, 7 = strongly agree. | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| New product flexibility Please circle the appropriate number to indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each of the following statements that measure the new product flexibility in your company. The item scales are seven-point Likert type scales with 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = slightly disagree, 4 = neutral, 5 = slightly agree, 6 = agree, 7 = strongly agree. | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Please select the number that accurately reflects the extent of your firm’s competitive advantage on each of the following. | |||||||

| Competitive advantage: Differentiation strategy | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Competitive advantage: Cost–leadership strategy | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

References

- Koufteros, X.; Cheng, T.; Lai, K. ‘Black-Box’ and ‘Gray-Box’ Supplier Integration in Product Development: Antecedents, Consequences, and the Moderating Role of Firm Size. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 847–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, R.K.; Tellis, G.J. Organizing for Radical Product Innovation: The Overlooked Role of Willingness to Cannibalize. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, S. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndubisi, N.O.; Dayan, M.; Yeniaras, V.; Al-Hawari, M. The effects of complementarity of knowledge and capabilities on joint innovation capabilities and service innovation: The role of competitive intensity and demand uncertainty. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 89, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, A. Concurrent Engineering, Knowledge Management, and Product Innovation. J. Oper. Strateg. Plan. 2018, 1, 204–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguia, C. Product innovation and the competitive advantage. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 1, 140–157. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; del Río, P.; Könnölä, T. Diversity of eco-innovations: Reflections from selected case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezen, B.; Çankaya, S.Y. Effects of Green Manufacturing and Eco-innovation on Sustainability Performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oltra, V.; Jean, M.S. Sectoral systems of environmental innovation: An application to the French automotive industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2009, 76, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürlek, M.; Koseoglu, M. Green innovation research in the field of hospitality and tourism: The construct, antecedents, consequences, and future outlook. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 734–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Long, H. Mechanism for Green Development Behavior and Performance of Industrial Enterprises (GDBP-IE) Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Parliament. Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme (2007 to 2013); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Fairhurst, A. The review of “green” research in hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzoglou, P.; Chatzoudes, D. The role of innovation in building competitive advantages: An empirical investigation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 21, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantazy, K.A.; Salem, M. The value of strategy and flexibility in new product development. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2016, 29, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, V.; Berente, N.; Lyytinen, K.; Gaskin, J. Team Design Thinking, Product Innovativeness, and the Moderating Role of Problem Unfamiliarity. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2020, 37, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhang, F.; Ji, J.; Teo, T.S.; Wang, T.; Liu, Z. Competitive intensity and new product development outcomes: The roles of knowledge integration and organizational unlearning. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 139, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Yang, C.-L.; Cheng, H.-C.; Sheu, C. Manufacturing flexibility and business strategy: An empirical study of small and medium sized firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 83, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Fantazy, K.A.; Kumar, U.; Boyle, T.A. Implementation and management framework for supply chain flexibility. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2006, 19, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, J.; Chandy, R.; Ellis, M. The Impact of Acquisitions on Innovation: Poison Pill, Placebo, or Tonic? J. Mark. 2005, 69, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márcio, A.; Thomé, A.; Scavarda, L.; Sílvio, R.; Ceryno, P.; Klingebiel, K. A multi-tier study on supply chain flexibility in the automotive industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 158, 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.; Mishra, O.N. Factor influencing flexibility in new product development: Empirical evidence from Indian manufacturing firms. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.; Ramaswami, S.N.; Patel, P.C.; Chai, L. Innovation-based strategic flexibility (ISF): Role of CEO ties with marketing and R&D. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettunen, J.; Grushka-Cockayne, Y.; Degraeve, Z.; De Reyck, B. New product development flexibility in a competitive environment. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 244, 892–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buganza, T.; Gerst, M.; Verganti, R. Adoption of NPD flexibility practices in new technology-based firms. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2010, 13, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Boon-Itt, S.; Wong, C. The contingency effects of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between supply chain integration and operational performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, A.D.M. Customer Integration during Innovation Development: An Exploratory Study in the Logistics Service Industry. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2012, 21, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.S.; Wu, F. Customer Involvement in Innovation: A Review of Literature and Future Research Directions. Innov. Strategy 2018, 15, 63–98. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, R.M.; Zacharias, N.A.; Schnellbaecher, A. How Do Strategy and Leadership Styles Jointly Affect Co-development and Its Innovation Outcomes? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 34, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, M.; Krogh, G. Organizing for open innovation: Focus on the integration of knowledge: Focus on the Integration of Knowledge. Organ. Dyn. 2010, 39, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.; Handfield, R.; Ragatz, G. Supplier Integration into New-Product Development: Coordinating Product, Process and Supply Chain Design. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.; Pujari, D.; Pontrandolfo, P. Green Product Innovation in Manufacturing Firms: A Sustainability-Oriented Dynamic Capability Perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 26, 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. Competitive Advantage; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Peteraf, M.A.; Barney, J.B. Unraveling the resource-based tangle. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2003, 24, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, G.; Barney, J.B.; Muhanna, W.A. Capabilities, business processes, and competitive advantage: Choosing the dependent variable in empirical tests of the resource-based view. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 25, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Franklin, A.; Martinette, L. Building a sustainable competitive advantage. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2013, 8, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Bentley, Y.; Cao, G.; Habib, F. Green supply chain management–food for thought? Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2017, 20, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.; Zelbst, P.; Meacham, J.; Bhadauria, V. Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrafi, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, V.; Mishra, N.; Ghobadian, A.; Elfezazi, S. Lean, green practices and process innovation: A model for green supply chain performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 206, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zheng, H.; Huang, Y.; Li, X. Considering Consumers’ Green Preferences and Government Subsidies in the Decision Making of the Construction and Demolition Waste Recycling Supply Chain: A Stackelberg Game Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Thongpapanl, N.; Dimov, D. A Closer Look at Cross-Functional Collaboration and Product Innovativeness: Contingency Effects of Structural and Relational Context. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2011, 28, 680–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Driver of Green Innovation and Green Image—Green Core Competence. J. Bus. Ethic. 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y. The effects of customer and supplier involvement on competitive advantage: An empirical study in China. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, M.; Olhager, J. Lean and agile manufacturing: External and internal drivers and performance outcomes. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2009, 29, 976–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, A.; Sethi, S. Flexibility in manufacturing: A survey. Int. J. Flex. Manuf. Syst. 1990, 2, 289–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.Z.; Yang, Q.; Waheed, A. Investment in intangible resources and capabilities spurs sustainable competitive advantage and firm performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 26, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.W.H.; Siah, M.W.; Ooi, K.-B.; Hew, T.S.; Chong, A. The adoption of PDA for future healthcare system: An emerging market perspective. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2015, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Yeung, J.H.Y. The impact of power and relationship commitment on the integration between manufacturers and customers in a supply chain. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 26, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Lai, K.K.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y. The impact of supplier integration on customer integration and new product performance: The mediating role of manufacturing flexibility under trust theory. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 147, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Unraveling the complex relationship between environmental and financial performance—A multilevel longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 219, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarolo, P. Is Integration Enough for Fast Product Development? An Empirical Investigation of the Contextual Effects of Product Vision. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2006, 24, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, T. Linking green customer and supplier integration with green innovation performance: The role of internal integration. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 1583–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melander, L. Customer and Supplier Collaboration in Green Product Innovation: External and Internal Capabilities. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2018, 27, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, Z.J.H.; Mochtar, J.; Basana, S.R.; Siagian, H. The effect of competency management on organizational performance through supply chain integration and quality. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 9, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivadas, E.; Dwyer, F.R. An Examination of Organizational Factors Influencing New Product Success in Internal and Alliance-Based Processes. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.S.; Tong, C. The influence of market orientation on new product success. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2012, 15, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, Z.J.H.; Siagian, H.; Jie, F. The Role of Top Management Commitment to Enhancing the Competitive Advantage Through ERP Integration and Purchasing Strategy. Int. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 16, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burki, U.; Ersoy, P.; Najam, U. Top Management, Green Innovations, and the Mediating Effect of Customer Cooperation in Green Supply Chains. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, H. Green Innovation Strategy and Ambidextrous Green Innovation: The Mediating Effects of Green Supply Chain Integration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.B.; Huo, B.; Zhao, X. The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 28, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.B.; Zsidisin, G.; Ragatz, G.L. Timing and Extent of Supplier Integration in New Product Development: A Contingency Approach. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2008, 44, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Modi, S.B.; Schoenherr, T. Leveraging sustainable design practices through supplier involvement in new product development: The role of the suppliers’ environmental management capability. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 232, 107919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kwon, I.; Severance, D. Relationships between supply chain performance and degree of linkage among supplier, internal integration and customer. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2007, 12, 444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Huo, B. The impact of supply chain quality integration on green supply chain management and environmental performance. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2017, 30, 1110–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, Q. Top management team faultlines, green technology innovation and firm financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 285, 112095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Liu, B.; Luo, F.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Wei, W. The effect of economic growth target constraints on green technology innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 292, 112765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersén, J. A relational natural-resource-based view on product innovation: The influence of green product innovation and green suppliers on differentiation advantage in small manufacturing firms. Technovation 2021, 104, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, B.; Mayer, S.; Nägele, F. Economic versus belief-based models: Shedding light on the adoption of novel green technologies. Energy Policy 2017, 101, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Liu, Z. Green innovations, supply chain integration and green information system: A model of moderation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industry | Number of Companies | Respondents | Percentage from the Total Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Textiles, Leather, and Clothing | 45 | 68 | 18% |

| Food and Beverages | 47 | 73 | 19% |

| Engineering, Electronics, and Construction | 35 | 75 | 20% |

| Ceramics and Glass, Mining and Extraction | 18 | 47 | 12% |

| Chemical and Pharmaceutical Products | 52 | 84 | 22% |

| Others: Paper and Cardboard | 19 | 31 | 8% |

| Indicators | Category | Number | Percentages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 249.00 | 65.87% |

| Female | 129.00 | 34.13% | |

| Age | Less than 25 Years | 101.00 | 26.17% |

| 26–35 Years | 82.00 | 21.69% | |

| 36–45 Years | 117.00 | 30.95% | |

| Over 45 Years | 78.00 | 20.63% | |

| Experience | Less than one year | 87.00 | 23.02% |

| 1 to 5 years | 136.00 | 35.98% | |

| Over five years | 155.00 | 41.01% | |

| Functional area | Marketing and sales | 236.00 | 62.16% |

| Operations | 71.00 | 18.78% | |

| Accounting or Finance | 32.00 | 8.47% | |

| Others | 39.00 | 10.31% | |

| Managerial level | Supervisor/manager | 274.00 | 72.48% |

| Senior management | 104.00 | 27.51% |

| Dimension | No. of Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Green Customer Integration | 6 | [43] |

| Green Supplier Integration | 4 | [43] |

| Green New Product Flexibility | 6 | [15] |

| Sustainable Green Product Innovation | 4 | [44,45] |

| Cost–Leadership Strategy | 4 | [46] |

| Differentiation Strategy | 4 | [46] |

| 28 |

| No. of Items | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Customer Integration | 6 | 4.21 | 0.97 | 0.69 | −0.06 | 93.6 |

| Green Supplier Integration | 4 | 4.77 | 0.99 | 0.14 | −0.70 | 81.8 |

| New Product Flexibility | 6 | 6.02 | 0.70 | −0.69 | 1.30 | 94.3 |

| Sustainable Green Product Innovation | 4 | 4.91 | 0.91 | 0.06 | −0.67 | 87.9 |

| Cost–Leadership Strategy | 4 | 5.98 | 0.65 | −0.75 | 1.90 | 84.1 |

| Differentiation Strategy | 4 | 5.82 | 0.76 | −0.83 | 1.48 | 87.7 |

| All | 28 | 5.24 | 0.84 | −0.18 | 0.47 | 84.7 |

| CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | GCI | NPF | GSPI | SGI | CLS | DIFS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCI | 0.945 | 0.709 | 0.062 | 0.948 | 0.842 | |||||

| NPF | 0.941 | 0.729 | 0.287 | 0.957 | −0.117 | 0.854 | ||||

| GSI | 0.819 | 0.531 | 0.166 | 0.820 | −0.189 | 0.284 | 0.729 | |||

| SGPI | 0.863 | 0.613 | 0.186 | 0.879 | −0.248 | 0.333 | 0.407 | 0.783 | ||

| CLS | 0.843 | 0.574 | 0.437 | 0.844 | −0.153 | 0.536 | 0.304 | 0.431 | 0.758 | |

| DIFS | 0.885 | 0.660 | 0.437 | 0.913 | −0.093 | 0.521 | 0.166 | 0.218 | 0.661 | 0.812 |

| CR: Composite Reliability AVE: Average Variance Extracted | MSV: Maximum Shared Variance MaxR(H): Maximal Reliability | |||||||||

| Green integration: GCI: Green Customer Integration GSI: Green Supplier Integration | ||||||||||

| NPF: New Product Flexibility | SGPI: Sustainable Green Product Innovation | |||||||||

| Competitive advantage CLS: Cost–Leadership Strategy DIFS: Differentiation Strategy | ||||||||||

| Goodness-of-Fit Measures | χ2/df (χ2, df) | p-Value | GFI | SRMR | CFI | NFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended value | ≤3.00 | ≥0.05 | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.08 |

| Measurement model | 1.90 (625.5, 329) | 0.00 | 0.898 | 0.03 | 0.960 | 0.920 | 0.954 | 0.049 |

| Structural model | 2.66 (725.5, 335) | 0.00 | 0.881 | 0.05 | 0.947 | 0.907 | 0.941 | 0.056 |

| Hypothesis/Path | Path Coefficient | Std. Error | Critical Ratio | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: GCI → NPF | 0.07 | 0.039 | 4.24 | *** | Supported |

| H2: GSI → NPF | 0.27 | 0.049 | 4.551 | *** | Supported |

| H3: NPF → SGPI | 0.16 | 0.044 | 3.100 | 0.002 | Supported |

| H4: GCI → SGPI | 0.32 | 0.063 | 4.591 | *** | Supported |

| H5: GSI → SGPI | 0.43 | 0.058 | 5.140 | *** | Supported |

| H6a: SGPI → CLS | 0.24 | 0.056 | 4.245 | *** | Supported |

| H6b: SGPI → DIFS | 0.45 | 0.039 | 7.328 | *** | Supported |

| Path | Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Result | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients | SE | p-Value | Bootstrapping 95% CI | Standardized Coefficients | SE | p-Value | Bootstrapping 95% CI | Standardized Coefficients | SE | p-Value | Bootstrapping 95% CI | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||

| GCI→ NPF→ SGI | 0.170 | 0.083 | 5.987 | 0.033 | 0.660 | 0.120 | 0.065 | 2.923 | 0.014 | 1.321 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 5.345 | 0.027 | 0.149 | Partial Supported |

| GSI→ NPF→ SGI | 0.270 | 0.059 | 6.572 | 0.243 | 0.682 | 0.160 | 0.041 | 4.021 | 0.015 | 0.292 | 0.110 | 0.083 | 6.750 | 0.087 | 0.209 | Partial Supported |

| GCI→ NPF→SGI → CLS | 0.276 | 0.061 | 3.092 | 0.112 | 0.369 | 0.106 | 0.037 | 1.901 | 0.003 | 0.257 | 0.170 | 0.040 | 7.150 | 0.147 | 0.269 | Supported |

| GCI→ NPF→SGI → DIFS | 0.198 | 0.064 | 2.980 | 0.037 | 0.215 | 0.108 | 0.067 | 1.423 | 0.092 | 0.217 | 0.090 | 0.923 | 6.090 | 0.067 | 0.189 | Supported |

| GSI→ NPF→ SGI → CLS | 0.107 | 0.037 | 3.757 | 0.022 | 0.555 | 0.027 | 0.084 | 0.500 | 0.015 | 0.162 | 0.080 | 0.150 | 7.020 | 0.057 | 0.179 | Supported |

| GSI→ NPF→ SGI → DIFS | 0.153 | 0.113 | 3.487 | 0.130 | 0.544 | 0.113 | 0.044 | 0.907 | 0.032 | 0.226 | 0.040 | 0.615 | 6.000 | 0.017 | 0.139 | Supported |

| NPF→ SCI → CLS | 0.219 | 0.135 | 3.588 | 0.024 | 0.197 | 0.109 | 0.038 | 1.570 | 0.086 | 0.282 | 0.110 | 0.049 | 3.560 | 0.087 | 0.209 | Supported |

| NPF→ SGI →DIFS | 0.175 | 0.117 | 2.967 | 0.037 | 0.185 | 0.115 | 0.134 | 1.451 | 0.032 | 0.260 | 0.060 | 0.902 | 4.253 | 0.037 | 0.159 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Awwad, A.; Anouze, A.L.M.; Ndubisi, N.O. Green Customer and Supplier Integration for Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Effect of Sustainable Product Innovation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10153. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610153

Awwad A, Anouze ALM, Ndubisi NO. Green Customer and Supplier Integration for Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Effect of Sustainable Product Innovation. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10153. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610153

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwwad, Abdulkareem, Abdel Latef M. Anouze, and Nelson Oly Ndubisi. 2022. "Green Customer and Supplier Integration for Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Effect of Sustainable Product Innovation" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10153. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610153

APA StyleAwwad, A., Anouze, A. L. M., & Ndubisi, N. O. (2022). Green Customer and Supplier Integration for Competitive Advantage: The Mediation Effect of Sustainable Product Innovation. Sustainability, 14(16), 10153. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610153