Green Advertising on Social Media: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

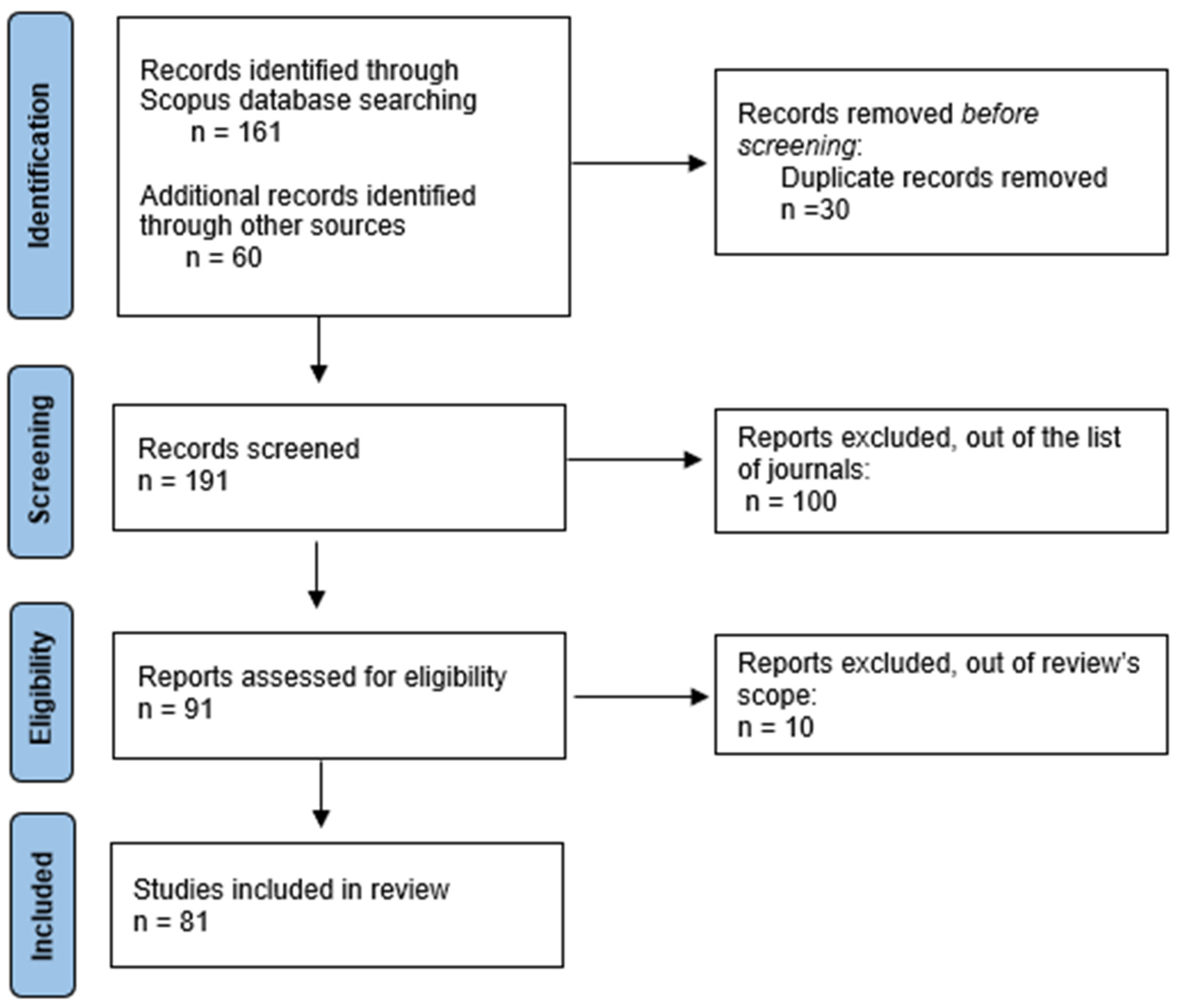

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Descriptive and Thematic Analysis

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

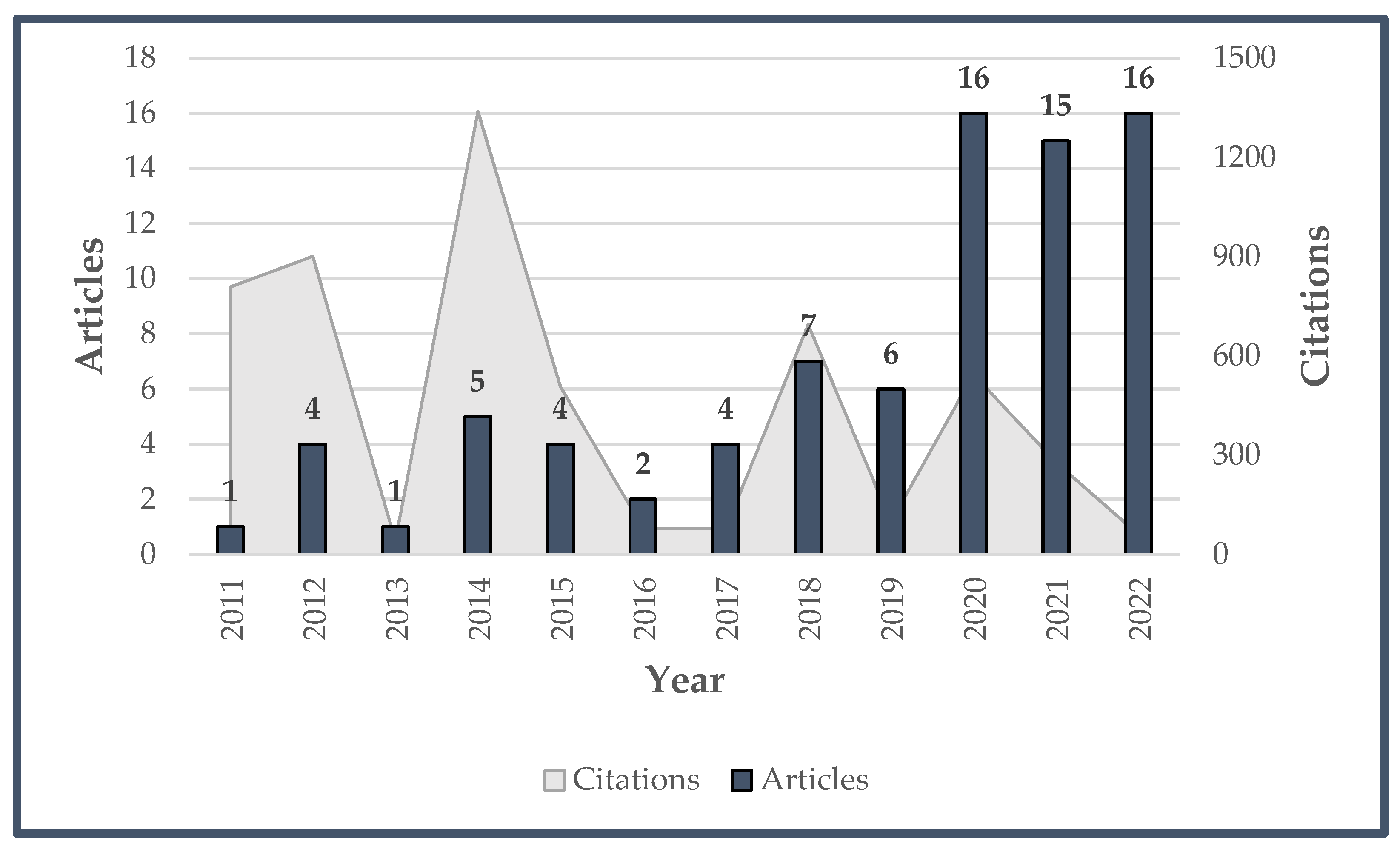

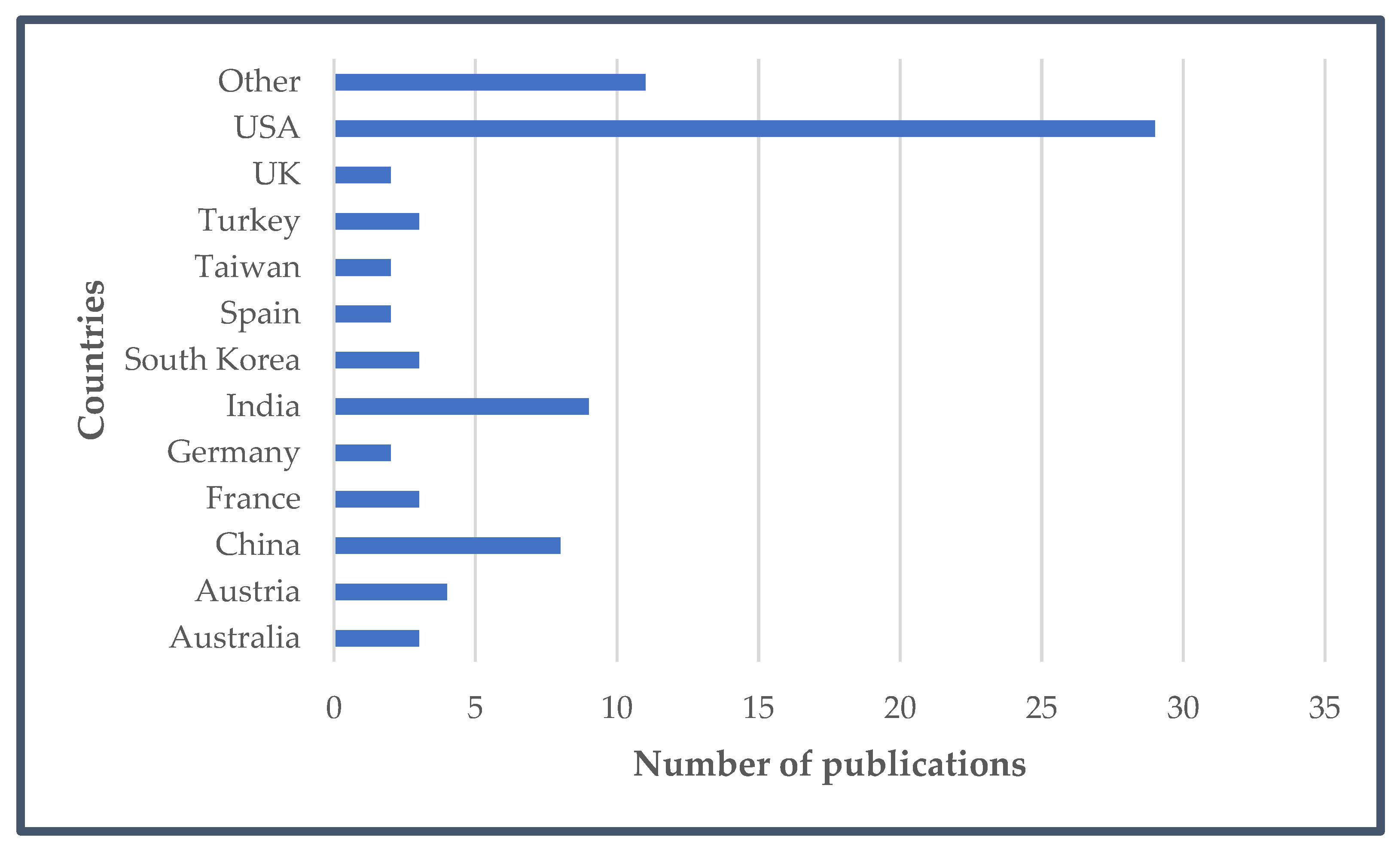

3.2. Year, Journal, and Geographic Distribution of the Literature

| Article | Authors | Year | No of Citations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How Sustainability Ratings Might Deter ‘Greenwashing’: A Closer Look at Ethical Corporate Communication | Parguel, B, Benoît-Moreau F, Larceneux F | 2011 | 808 | [19] |

| Perceived greenwashing: The interactive effects of green advertising and corporate environmental performance on consumer reactions | Nyilasy G, Gangadharbatia H, Paladino A | 2014 | 498 | [20] |

| Go Green! Should Environmental Messages be So Assertive? | Kronrod A, Grinstein A, Wathieu L | 2012 | 451 | [21] |

| Green Claims and Message Frames: How Green New Products Change Brand Attitude | Olsen M, Slotegraaf R, Chandukala S | 2014 | 450 | [25] |

| Sustainable marketing and social media: A cross-country analysis of motives for sustainable behaviors | Minron E, Lee C, Orth U, Kim C, Kahle L | 2012 | 268 | [26] |

| Corporate communication, sustainability, and social media: It’s not easy (really) being green | Reilly A, Hynan K | 2014 | 262 | [27] |

| Message framing in green advertising: The effect of construal level and consumer environmental concern | Chang H, Zhang L, Xie G | 2015 | 247 | [28] |

| The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: The mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern | Zhang L, Li D, Cao C, Huang S | 2018 | 217 | [29] |

| Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising | Schmuck D, Matthes J, Naderer B | 2018 | 206 | [30] |

| Can evoking nature in advertising mislead consumers? The power of ‘executional greenwashing’ | Parguel B, Benoit-Moreaou, F., & Russell, C. A. | 2015 | 203 | [31] |

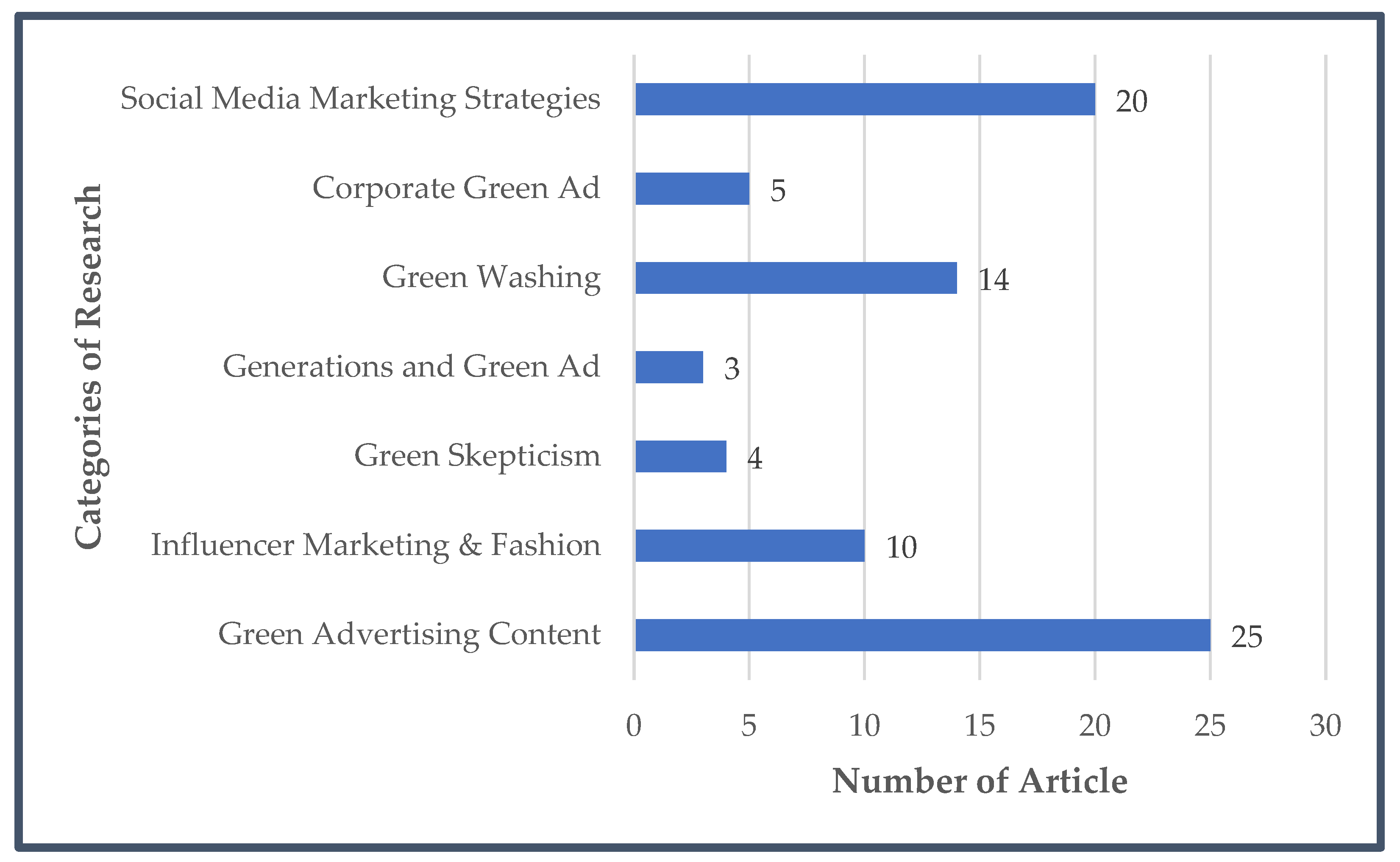

3.3. Thematic Analysis

3.3.1. Green Advertising Content

3.3.2. Greenwashing

3.3.3. Green Skepticism

3.3.4. Generations and Green Advertising

3.3.5. Influencer Marketing and Green Advertising

3.3.6. Corporate Green Advertising

3.3.7. Social Media Marketing Strategies

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations, Research Gaps, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Theories and Model | Sample References |

|---|---|

| Agenda Setting Theory | [68] |

| AIDA Model | [67] |

| Altruistic Consumer Utility | [74] |

| ARI Model | [30] |

| Anthropological Theory of Consumer Behavior | [59] |

| Attitude Behavior Context Theory | [29] |

| Conspicuous Consumption Theory | [37] |

| Construal Level Theory | [28,38] |

| Dual Coding Theory | [33] |

| Ecologically Conscious Consumer Behavior | [85] |

| Economic Theory of Consumer Behavior | [59] |

| Elaboration Likelihood Model | [40,54] |

| Fuzzy Reasoning Theory | [56] |

| Guilt Appeals Theory | [2] |

| Information Adoption Model | [79] |

| Institutional Theory | [69] |

| Legitimacy Theory | [69] |

| Marketing Theory of Consumer Behavior | [59] |

| McGuire Communication Persuasion Matrix | [32] |

| Natural Resource Based View Theory | [77] |

| Persuasion Knowledge Model | [76] |

| Psychological Theory of Consumer Behavior | [59] |

| Priming Theory | [35] |

| Prospect Theory | [28,34,41] |

| Psychophysiology Theory | [41] |

| Schema Incongruity Processing Theory | [75] |

| Signaling Theory | [50,57] |

| Social Impact Theory | [66] |

| Social Judgement Theory | [39] |

| Social Media information Sharing | [65] |

| Social Norms Theory | [24] |

| Stimulus Organism Response Model | [50] |

| Technologies for Pro-Environmental Action Model | [94] |

| Theory of Consumption Values | [89] |

| Theory of Planned Behavior | [22] |

| Theory of Reactance | [75] |

| Theory of Reasoned Action | [62] |

| Underpinning Theory | [90] |

| Uses and Gratification Theory | [94] |

| Dependent Variables | Independent Variables | Mediators | Moderators | Authors | Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad deceptiveness | Literacy intervention | Fernandes et al. 2020 | [76] | ||

| Ad trust | Literacy intervention | Fernandes et al. 2020 | [76] | ||

| Advertising effect | Environmental protecting emotion, green advertising design | Emotions | Kao & Du, 2020 | [40] | |

| Attention | Issue frame as hope or fear | Lee et al. 2017 | [49] | ||

| Attitude toward climate change | Emotion (fear or hope) | S. Park, 2020 | [47] | ||

| Attitude toward ad | Literacy intervention | Fernandes et al. 2020 | [76] | ||

| Message appeal | Message objectivity | H. Chang et al., 2015 | [28] | ||

| Environmental involvement | Sahin et al., 2020 | [33] | |||

| Message framing | Issue involvement | Lee & Cho, 2021 | [34] | ||

| Consumers’ confusion, green message type | Green trust | Product type | Lim et al., 2021 | [45] | |

| Vague/false/combined vague/combined/false greenwashing claim | Environmental involvement, perceived greenwashing, virtual nature experience | Schmuck et al., 2018 | [30] | ||

| Attitude toward brand | Message appeal | Message objectivity | H. Chang et al., 2015 | [28] | |

| Message framing | Issue involvement | Lee & Cho, 2021 | [34] | ||

| Literacy intervention | Fernandes et al. 2020 | [76] | |||

| Brand evaluation | Ad believability, brand positioning, green message | Vilasanti da Luz et al., 2020 | [36] | ||

| Vague/false/combined vague/combined/false greenwashing claim | Environmental involvement, perceived greenwashing, virtual nature experience | Schmuck et al., 2018 | [30] | ||

| Green advertising, corporate environmental performance | Nyilasy et al., 2012 | [71] | |||

| Attitude toward the green issue | Issue frame as hope or fear | Lee et al. 2017 | [29] | ||

| Attitude toward the hotel | Environmental involvement | Sahin et al., 2020 | [33] | ||

| Attitude toward the product | Entertainment, interaction, customization, trendiness, word of mouth | Gupta & Syed 2022 | [94] | ||

| Consumers’ intentions to purchase green products, consumers’ price consciousness | Sun & Wang, 2020 | [22] | |||

| Environmental concern, company credibility, purchase credibility | Stokes & M. Turri, 2015 | [92] | |||

| Influencer type, popularity metrics | Pittman & Abell, 2021 | [54] | |||

| Advertising appeal, environmental consciousness, issue proximity | C.T Chang, 2012 | [2] | |||

| Behavioral intentions | Green information on webpage (firm-initiated vs. customer-generated green information) | Customers’ green consciousness | E. Park et al., 2021 | [96] | |

| Issue frame as hope or fear | Lee et al. 2017 | [49] | |||

| Advertising appeal, environmental consciousness, issue proximity | C.T Chang, 2012 | [2] | |||

| Brand evaluation | Abstract/concrete/vague/false/control compensation condition | Topical environmental knowledge, perceived greenwashing | Neureiter & Matthes, 2022 | [75] | |

| Sustainability/fashion consciousness, purchase behavior and attitude, fashion purchase behavior and attitude, ad skepticism, attitude towards Black Friday | Sailer et al., 2022 | [72] | |||

| Business performance | Green packaging, green advertising | Competitive advantage | Maziriri, 2020 | [77] | |

| Company attitude | Green appeal/green message from company | Receptivity to green advertising | Bailey et al., 2016 | [85] | |

| Company evaluation | Message appeals | Message objectivity | Kang & Sung, 2022 | [37] | |

| Company trustworthiness | Green appeal/green message from company | Receptivity to green advertising | Bailey et al., 2016 | [85] | |

| Consumer behavior | Sustainability perception | Brand attitude | Trust, brand luxury | Kong et al. 2021 | [23] |

| Consumer engagement | Ad appeal, benefit association, involvement | Self-enhancement | Kyu Kim et al., 2020 | [38] | |

| Consumption values | Responsible consumption behaviors, responsible consumption reintention, social media behaviors | Burucuoglu & Erdogan, 2019 | [89] | ||

| Corporate brand evaluations | Sustainability ratings, intrinsic/extrinsic motives | Parguel et al., 2011 | [19] | ||

| Customer attitudes | Green information on webpage (firm-initiated vs. customer-generated green information) | Customers’ green consciousness | E. Park et al., 2021 | [96] | |

| Digital engagement | Fear appeals, information appeals | Pollution ideation | Pittman et Al., 2021 | [39] | |

| Electronic word of mouth | Emotion, CRM, image, environmental attitudes | Tanford et al., 2020 | [35] | ||

| Environmental attitude | News media, social media, digital engagement | Brand quality, brand authenticity | Pittman et al., 2022 | [24] | |

| Ethical positions | Consumption values, responsible consumption behaviors, social media behaviors | Burucuoglu & Erdogan, 2019 | [89] | ||

| Fight shame | Abstract/concrete/vague/false/control compensation condition | Topical environmental knowledge, perceived greenwashing | Neureiter & Matthes, 2022 | [75] | |

| Government support | Emotion (fear or hope) | S. Park, 2020 | [47] | ||

| Green advertising | Greenwashing attributes in NGO blogs/in newspaper articles | Fernando et al., 2014 | [68] | ||

| Green brand credibility | Green buying behavior | Green advertisement, green brand evaluation | Mansoor et al., 2022 | [44] | |

| Green brand knowledge | Green buying behavior | Green advertisement, green brand evaluation | Mansoor et al., 2022 | [44] | |

| Green consumer behavior | Environmental awareness, environmental concern, self-image, self-influence, ethics | Gandhi & Sheorey, 2019 | [87] | ||

| Green consumption values | Eco brand social media, Eco label | Motivation | Environmental concern | Chi, 2021 | [93] |

| Green evaluations | Message style, message sidedness, message specificity | Message credibility | Kim et al., 2022 | [48] | |

| Green messages of for-profits | Message orientation and framing | Shin & Ki, 2022 | [51] | ||

| Green messages of non-profits | Message specificity and environmental issues and additional features in content | Shin & Ki, 2022 | [51] | ||

| Green perception | Green information on webpage (firm-initiated vs. customer-generated green information) | Customers’ green consciousness | E. Park et al., 2021 | [96] | |

| Green purchase behavior | Social influence, self-image, environmental concern | Green advertising | Ghouri et al., 2018 | [90] | |

| Receptivity to green advertising, personal norm, environmental consciousness | Understanding greenwashing | Jog & Singhal, 2020 | [73] | ||

| Image | Emotion, CRM, image, environmental attitudes | Tanford et al., 2020 | [35] | ||

| Intention to stay at the eco-friendly hotel | Message appeal | Message source, perceived Environmental CSR | Kapoor et al., 2021 | [32] | |

| Interdependent self-construal | Green advertising skepticism | Information utility | Luo et al., 2020 | [61] | |

| Message attitude | Green appeal/green message from company | Receptivity to green advertising | Bailey et al., 2016 | [85] | |

| Participation in activism | Emotion (fear or hope) | S. Park, 2020 | [47] | ||

| Perceived behavior control | Consumers’ intentions to purchase green products, consumers’ price consciousness, attitude toward green products | Sun & Wang, 2020 | [22] | ||

| Perceived consumer effectiveness | Consumers’ intentions to purchase green products, consumers’ price consciousness, attitude toward green products | Sun & Wang, 2020 | [22] | ||

| Perceived effort | Sustainability ratings, intrinsic/extrinsic motives | Parguel et al., 2011 | [19] | ||

| Perceived environmental CSR | Message appeal | Message source, perceived environmental CSR | Kapoor et al., 2021 | [32] | |

| Perceived motive toward a CSR activity | Message appeals | Message objectivity | Kang & Sung, 2022 | [37] | |

| Perceived SME profitability | Green marketing dimensions | Green purchase behavior | Martins, 2022 | [55] | |

| Product knowledge | Consumers’ intentions to purchase green products, consumers’ price consciousness, attitude toward green products | Sun & Wang, 2020 | [22] | ||

| Purchase intentions | Emotion, CRM, image, environmental attitudes | Tanford et al., 2020 | [35] | ||

| Social media usage, online interpersonal influence | Femininity, masculinity individualism/collectivism | Bedard & Tolmie, 2018 | [66] | ||

| Social media information sharing | Subjective norms, perceived green value | Occupation | Sun & Xing, 2022 | [65] | |

| Green WOM, greenwashing perception | Green concern | Zhang et al., 2018 | [29] | ||

| Green advertising skepticism | Information utility | Luo et al., 2020 | [61] | ||

| Green appeal/green message from company | Receptivity to green advertising | Bailey et al., 2016 | [85] | ||

| Consumers’ confusion, green message type | Green trust | Product type | Lim et al., 2021 | [45] | |

| Celebrity credibility | Aad, Ab | Kumar & Tripathi, 2022 | [52] | ||

| Influencer type, popularity metrics | Pittman & Abell, 2021 | [54] | |||

| Price value, environmental concern | Brand trust | Ulusoy & Barretta, 2016 | [62] | ||

| Fear appeals, information appeals | Pollution ideation | Pittman et al., 2021 | [39] | ||

| Message appeal | Message objectivity | H. Chang et al., 2015 | [28] | ||

| Message framing | Issue involvement | Lee & Cho, 2021 | [34] | ||

| Environmental involvement | Sahin et al. 2020 | [34] | |||

| News media, social media, digital engagement | Brand quality, Brand authenticity | Pittman et al., 2022 | [24] | ||

| Self-Enhancement | Ad appeal, benefit association, involvement | Self-Enhancement | Kyu Kim et al., 2020 | [38] | |

| Skepticism | Literacy intervention | Fernandes et al. 2020 | [76] | ||

| Social media | Subjective norms, price consciousness, perceived consumer effectiveness, product knowledge | Sun & Wang, 2020 | [22] | ||

| Subjective norms | Consumers’ intentions to purchase green products, consumers’ price consciousness, attitude toward green products | Sun & Wang, 2020 | [22] | ||

| Support intentions | Green appeal/green message from company | Receptivity to green advertising | Bailey et al., 2016 | [85] | |

| Sustainability evaluation | Sustainability/fashion consciousness, purchase behavior and attitude, fashion purchase behavior and attitude, ad skepticism, attitude towards Black Friday | Sailer et al., 2022 | [72] | ||

| Sustainable behavior | Emotion (fear or hope) | S. Park, 2020 | [47] | ||

| Sustainable intentions | Emoji factor | Social media engagement | Baek et al., 2022 | [46] | |

| Trust | Green advertising receptivity, intention to buy eco-labeled products | Regulatory focus | Sun et al., 2021 | [50] | |

| Willingness to buy | Brand evaluation | Ad believability, brand positioning, green message | Vilasanti da Luz et al., 2020 | [36] | |

| Willingness to pay | Entertainment, interaction, customization, trendiness, word of mouth | Gupta & Syed 2022 | [94] | ||

| Emotion, CRM, image, environmental attitudes | Tanford et al., 2020 | [35] | |||

| Word of mouth | Emotion, CRM, image, environmental attitudes | Tanford et al., 2020 | [35] | ||

| Influencer type, popularity metrics | Pittman & Abell, 2021 | [54] |

References

- Chan, R.Y.K. The Effectiveness of Environmental Advertising: The Role of Claim Type and the Source Country Green Image. Int. J. Advert. 2000, 19, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T. Are Guilt Appeals a Panacea in Green Advertising? The Right Formula of Issue Proximity and Environmental Consciousness. Int. J. Advert. 2012, 31, 741–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Green Advertising Revisited. Int. J. Advert. 2009, 28, 715–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zhang, L. When Does Green Advertising Work? The Moderating Role of Product Type. J. Mark. Commun. 2014, 20, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhwerk, M.E.; Lefkoff-Hagius, R. Green or Non-Green? Does Type of Appeal Matter When Advertising a Green Product? J. Advert. 1995, 24, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Gulas, C.S.; Iyer, E. Shades of Green: A Multidimensional Analysis of Environmental Advertising. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkhan, G.M.; Carlson, L. Green Advertising and the Reluctant Consumer. J. Advert. 1995, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangis, P. Concerns about Green Marketing. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1992, 4, 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, I.; Karagouni, G.; Trigkas, M.; Platogianni, E. Green Marketing the Case of Greece in Certified and Sustainably Managed Timber Products. EuroMed J. Bus. 2010, 5, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital 2022: Another Year of Bumper Growth—We Are Social UK. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/uk/blog/2022/01/digital-2022-another-year-of-bumper-growth-2/?fbclid=IwAR3kAIPubXGETC3goDrX--92iRWSDutTDa7PDxQfVcmykYau72_YLTiWkkY (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Kumar, A.; Moore, D.; Kannan, P.K.; Tyser, R.J.; Smith, R.H. From Social to Sale: The Effects of Firm Generated Content in Social Media on Customer Behavior. J. Mark. 2015, 80, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advertising Spending in the U.S. by Medium 2025|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/191926/us-ad-spending-by-medium-in-2009/ (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Agarwal, N.D.; Kumar, V.V.R. Three Decades of Green Advertising—A Review of Literature and Bibliometric Analysis. Benchmarking 2020, 28, 1934–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.R.; Carlson, L. The Future of Advertising Research: New Directions and Research Needs. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Estarli, M.; Barrera, E.S.A.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Y Diet. 2016, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-Analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCOB-Journal-List-2021-2022; Jordan Applied University College of Hospitality and Tourism Education: Jordan, NJ, USA, 2022.

- Parguel, B.; Benoît-Moreau, F.; Larceneux, F. How Sustainability Ratings Might Deter “Greenwashing”: A Closer Look at Ethical Corporate Communication. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Perceived Greenwashing: The Interactive Effects of Green Advertising and Corporate Environmental Performance on Consumer Reactions. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronrod, A.; Grinstein, A.; Wathieu, L. Go Green! Should Environmental Messages Be So Assertive? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S. Understanding Consumers’ Intentions to Purchase Green Products in the Social Media Marketing Context. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.M.; Witmaier, A.; Ko, E. Sustainability and Social Media Communication: How Consumers Respond to Marketing Efforts of Luxury and Non-Luxury Fashion Brands. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Oeldorf-Hirsch, A.; Brannan, A. Green Advertising on Social Media: Brand Authenticity Mediates the Effect of Different Appeals on Purchase Intent and Digital Engagement. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2022, 43, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green Claims and Message Frames: How Green New Products Change Brand Attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, E.; Lee, C.; Orth, U.; Kim, C.H.; Kahle, L. Sustainable Marketing and Social Media. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, A.H.; Hynan, K.A. Corporate Communication, Sustainability, and Social Media: It’s Not Easy (Really) Being Green. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xie, G.X. Message Framing in Green Advertising: The Effect of Construal Level and Consumer Environmental Concern. Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The Influence of Greenwashing Perception on Green Purchasing Intentions: The Mediating Role of Green Word-of-Mouth and Moderating Role of Green Concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D.; Matthes, J.; Naderer, B. Misleading Consumers with Green Advertising? An Affect–Reason–Involvement Account of Greenwashing Effects in Environmental Advertising. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parguel, B.; Benoit-Moreau, F.; Russell, C.A. Can Evoking Nature in Advertising Mislead Consumers? The Power of ‘Executional Greenwashing.’ Int. J. Advert. 2015, 34, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, P.S.; Balaji, M.S.; Jiang, Y. Effectiveness of Sustainability Communication on Social Media: Role of Message Appeal and Message Source. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 949–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S.; Baloglu, S.; Topcuoglu, E. The Influence of Green Message Types on Advertising Effectiveness for Luxury and Budget Hotel Segments. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 61, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Cho, M. The (in)Congruency Effects of Message Framing and Image Valence on Consumers’ Responses to Green Advertising: Focus on Issue Involvement as a Moderator. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 28, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, E.J. Priming Social Media and Framing Cause-Related Marketing to Promote Sustainable Hotel Choice. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1762–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilasanti da Luz, V.; Mantovani, D.; Nepomuceno, M.V. Matching Green Messages with Brand Positioning to Improve Brand Evaluation. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.Y.; Sung, Y.H. Luxury and Sustainability: The Role of Message Appeals and Objectivity on Luxury Brands’ Green Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mark. Commun. 2022, 28, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyu Kim, Y.; Yim, M.Y.C.; Kim, E.; Reeves, W. Exploring the Optimized Social Advertising Strategy That Can Generate Consumer Engagement with Green Messages on Social Media. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2020, 15, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Read, G.L.; Chen, J. Changing Attitudes on Social Media: Effects of Fear and Information in Green Advertising on Non-Green Consumers. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2021, 42, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.F.; Du, Y.Z. A Study on the Influence of Green Advertising Design and Environmental Emotion on Advertising Effect. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fiestas, M.; del Jesus, M.I.V.; Sanchez-Fernandez, J.; Montoro-Rios, F. A Psychophysiological Approach for Measuring Response to Messaging: How Consumers Emotionally Process Green Advertising. J. Advert. Res. 2015, 55, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, B.; Grimes, A. Measures That Can Boost Outcomes from Environmental Product Claims. J. Advert. Res. 2018, 58, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, F.; Föhl, U.; Walter, N.; Demmer, V. Green or Social? An Analysis of Environmental and Social Sustainability Advertising and Its Impact on Brand Personality, Credibility and Attitude. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Saeed, A.; Rustandi Kartawinata, B.; Naqi Khan, M.K. Derivers of Green Buying Behavior for Organic Skincare Products through an Interplay of Green Brand Evaluation and Green Advertisement. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.J.; Youn, N.; Eom, H.J. Green Advertising for the Sustainable Luxury Market. Australas. Mark. J. 2021, 29, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Kim, S.; Yoon, S.; Choi, Y.K.; Choi, D.; Bang, H. Emojis and Assertive Environmental Messages in Social Media Campaigns. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 988–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. How Celebrities’ Green Messages on Twitter Influence Public Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions to Mitigate Climate Change. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Anna) Kim, E.; Shoenberger, H.; (Penny) Kwon, E.; Ratneshwar, S. A Narrative Approach for Overcoming the Message Credibility Problem in Green Advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Chang, C.T.; Chen, P.C. What Sells Better in Green Communications: Fear or Hope? It Depends on Whether the Issue Is Global or Local. J. Advert. Res. 2017, 57, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, B.; Wang, S.; Fang, W. What You See Is Meaningful: Does Green Advertising Change the Intentions of Consumers to Purchase Eco-Labeled Products? Bus Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Ki, E.J. Understanding Environmental Tweets of For-Profits and Nonprofits and Their Effects on User Responses. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Tripathi, V. Green Advertising: Examining the Role of Celebrity’s Credibility Using SEM Approach. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2022, 23, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielki, J. Analysis of the Role of Digital Influencers and Their Impact on the Functioning of the Contemporary On-Line Promotional System and Its Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Abell, A. More Trust in Fewer Followers: Diverging Effects of Popularity Metrics and Green Orientation Social Media Influencers. J. Interact. Mark. 2021, 56, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A. Green Marketing and Perceived SME Profitability: The Meditating Effect of Green Purchase Behaviour. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüller, D.; Doubravský, K. Fuzzy Similarity Used by Micro-Enterprises in Marketing Communication for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L.; Krishen, A.S. Signaling Green! Firm ESG Signals in an Interconnected Environment That Promote Brand Valuation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydges, T.; Henninger, C.E.; Hanlon, M. Selling Sustainability: Investigating How Swedish Fashion Brands Communicate Sustainability to Consumers. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P. Consumer Attitude towards Sustainability of Fast Fashion Products in the UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Lee, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Advertising in Social Media: A Content Analysis of the Fashion Industry’s CSR Advertising on Instagram. Corp. Commun. 2021, 26, 700–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Xia, L. How Does Green Advertising Skepticism on Social Media Affect Consumer Intention to Purchase Green Products? J. Consum. Behav. 2020, 19, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, E.; Barretta, P.G. How Green Are You, Really? Consumers’ Skepticism toward Brands with Green Claims. J. Glob. Responsib. 2016, 7, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Y.; Wicaksono, H. Advancing on the Analysis of Causes and Consequences of Green Skepticism. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V. Exploring Skepticism toward Green Advertising: An ISM Approach. Int. J. Bus. Anal. Intell. 2017, 5, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, J. The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, S.A.N.; Tolmie, C.R. Millennials’ Green Consumption Behaviour: Exploring the Role of Social Media. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Pandey, N.; Jha, S. Promotion of Green Products on Facebook: Insights from Millennials. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 2020, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A.G.; Suganthi, L.; Sivakumaran, B. If You Blog, Will They Follow? Using Online Media to Set the Agenda for Consumer Concerns on “Greenwashed” Environmental Claims. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hora, M.; Subramanian, R. Relationship between Positive Environmental Disclosures and Environmental Performance: An Empirical Investigation of the Greenwashing Sin of the Hidden Trade-Off. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topal, İ.; Nart, S.; Akar, C.; Erkollar, A. The Effect of Greenwashing on Online Consumer Engagement: A Comparative Study in France, Germany, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyilasy, G.; Gangadharbatla, H.; Paladino, A. Greenwashing: A Consumer Perspective. Econ. Sociol. 2012, 5, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Sailer, A.; Wilfing, H.; Straus, E. Greenwashing and Bluewashing in Black Friday-Related Sustainable Fashion Marketing on Instagram. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jog, D.; Singhal, D. Greenwashing Understanding Among Indian Consumers and Its Impact on Their Green Consumption. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.B.; Cruz, J.M.; Shankar, R. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Issues in Supply Chain Competition: Should Greenwashing Be Regulated? Decis. Sci. 2018, 49, 1088–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neureiter, A.; Matthes, J. Comparing the Effects of Greenwashing Claims in Environmental Airline Advertising: Perceived Greenwashing, Brand Evaluation, and Flight Shame. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Segev, S.; Leopold, J.K. When Consumers Learn to Spot Deception in Advertising: Testing a Literacy Intervention to Combat Greenwashing. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 1115–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziriri, E.T. Green Packaging and Green Advertising as Precursors of Competitive Advantage and Business Performance among Manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises in South Africa. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1719586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, J.; Huising, R.; Struben, J. “What If Technology Worked in Harmony with Nature?” Imagining Climate Change through Prius Advertisements. Organization 2013, 20, 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, H.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Megicks, P. Determinants of Corporate Sustainability Message Sharing on Social Media: A Configuration Approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 633–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, H.E. Corporate Greenfluencing: A Case Study of Sponsorship Activation in Formula E Motorsports. Int. J. Sport. Mark. Spons. 2020, 21, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Simone, L.; Pezoa, M. Urban Shopping Malls and Sustainability Approaches in Chilean Cities: Relations between Environmental Impacts of Buildings and Greenwashing Branding Discourses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, L.; Jiang, H. Understanding Green Consumption: A Literature Review Based on Factor Analysis and Bibliometric Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, A.; Kazançoğlu, İ. Understanding Consumers’ Purchase Intentions toward Natural-Claimed Products: A Qualitative Research in Personal Care Products. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, C.A.; Royne, M.B. Thinking Green: How Marketing Managers Select Media for Consumer Acceptance. J. Bus. Strategy 2018, 39, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.; Tiamiyu, M.F. Green Advertising Receptivity: An Initial Scale Development Process. J. Mark. Commun. 2016, 22, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J. Uncharted Territory in Research on Environmental Advertising: Toward an Organizing Framework. J. Advert. 2019, 48, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.; Sheorey, P. Antecedents of Green Consumer Behaviour: A Study of Consumers in a Developing Country like India. Int. J. Public Sect. Perform. Manag. 2019, 5, 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Kwon, G.; Shin, H.J.; Yang, S.; Lee, S.; Suh, M. The Spell of Green: Can Frontal EEG Activations Identify Green Consumers? J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burucuoglu, M.; Erdogan, E. The Role of Ethical Positions on Responsible Consumption Behaviours and Consumption Values Regarding the Green Products. Glob. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 21, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouri, A.M.; Amin, M.; Haq, U.; Haq, M.A. Green Purchase Behavior and Social Practices. Manag. Res. J. 2018, 8, 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- Brécard, D. Consumer Misperception of Eco-Labels, Green Market Structure and Welfare. J. Regul. Econ. 2017, 51, 340–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, A.; Turri, A.M. Consumer Perceptions of Carbon Labeling in Print Advertising: Hype or Effective Communication Strategy? J. Mark. Commun. 2015, 21, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.T.K. Understanding the Effects of Eco-Label, Eco-Brand, and Social Media on Green Consumption Intention in Ecotourism Destinations. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Syed, A.A. Impact of Online Social Media Activities on Marketing of Green Products. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022, 30, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Mishra, T.; Kalro, A.D.; Bapat, V. Environmental Claims in Indian Print Advertising: An Empirical Study and Policy Recommendation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kwon, J.; Kim, S.B. Green Marketing Strategies on Online Platforms: A Mixed Approach of Experiment Design and Topic Modeling. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, E.; Banerjee, B. Anatomy of Green Advertising. Assoc. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.J. Consumer Response to Corporate Environmental Advertising. J. Consum. Mark. 1994, 11, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TerraChoice Environmental Marketing Inc. The “Six Sins of Greenwashing TM” A Study of Environmental Claims in North American Consumer Markets; TerraChoice Environmental Marketing Inc.: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray Shades of Green: Causes and Consequences of Green Skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Diamond, S. Social Media Marketing for Dummies, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Liu, X. Culture and Green Advertising Preference: A Comparative and Critical Discursive Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M. Keeping an Eye on the Mirror: Image and Identity in Organizational Adaptation. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 517–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghiemstra, R. Corporate Communication and Impression Management—New Perspectives Why Companies Engage in Corporate Social Reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 27, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Exec Suggests Instagram and TikTok Are Eating into Google’s Core Products, Search and Maps|TechCrunch. Available online: https://techcrunch.com/2022/07/12/google-exec-suggests-instagram-and-tiktok-are-eating-into-googles-core-products-search-and-maps/?tpcc=tcplustwitter&guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly9hYmNuZXdzLmdvLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAGJPR4JtcGApxKYZVpSaSR4K4eyGgBwbduXmU541rR_a8LOu8B8hSO1RpsyNoCvhq6gL8kNpyO23zKV4AHOeCUhR2WHcP0EpyWRwIf-Ni54jbvJ2oRHbxciSOmCbUiQTq9uPqukbossCMOK0LWWxjgzBoL39Ua4aUuVVC1aK25yC&fbclid=IwAR1snemwQOCuwGP1SkgcBAeK5fSKRQ31dED-pqQH7CQYixN5Fu8O6QXxRIE (accessed on 25 September 2022).

| Journal Title | No Articles | Impact Factor | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | 9 | 3.889 | 162 |

| International Journal of Advertising | 5 | 5.888 | 609 |

| Journal of Advertising | 4 | 6.528 | 564 |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 4 | 10.801 | 101 |

| Journal of Business Research | 4 | 10.969 | 93 |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 4 | 11.072 | 329 |

| Journal of Marketing Communications | 4 | 5.5 | 63 |

| Journal of Advertising Research | 3 | 3.0341 | 68 |

| Journal of Business ethics | 3 | 6.331 | 1.365 |

| Global Business Review | 2 | 2.195 | 18 |

| Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising | 2 | 0 | 24 |

| Others | 37 | - | - |

| Paper Type | Method | Total | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical | Literature Review | 3 | 3.44% |

| Research Paper | 78 | 96.56% | |

| Overall Total | 81 | 100% |

| Main Topic | Sample References |

|---|---|

| Green Advertising Content | [2,21,24,26,28,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] |

| Influencer Marketing & Fashion | [23,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] |

| Green Skepticism | [61,62,63,64] |

| Generations and Green Ad | [65,66,67] |

| Green Washing | [19,20,29,30,31,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] |

| Corporate Green Ad | [27,77,78,79,80] |

| Social Media Marketing Strategies | [13,14,22,26,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96] |

| Definitions | Authors | Sample References |

|---|---|---|

| Green advertising is defined as any ad that meets one or more of the following criteria: 1. Explicitly or implicitly addresses the relationship between a product/service and the biophysical environment. 2. Promotes a green lifestyle with or without highlighting a product/service. 3. Presents a corporate image of environmental responsibility. | Iyer and Banerjee 1993; Banerjee, Gulas, and Iyer 1995 | [6,97] |

| Advertising messages promoting sustainable goods or services are often labeled as green advertising. | Minton et al. 2012 | [26] |

| Environmental advertising, also referred to as green advertising, can be defined as the attempt to influence consumers’ cognitions, attitudes, and behaviors by promoting environmentally friendly features in the production, distribution, or recycling of products or services. | Matthes 2019 | [86] |

| Corporate environmental advertising typically contains three elements. First, the advertisement presents a general statement of corporate concern for the environment. Second, the advertisement describes how the corporation has initiated a number of activities which demonstrate its concern and commitment to environmental improvement. Third, the advertisement provides a description of specific environmentally related activities in which the corporation is engaged and/or outcomes for which the corporation takes credit. | Davis 1994 | [98] |

| Green advertising is defined as “promotional messages that may appeal to the needs and desires of environmentally concerned consumers.” | Zinkhan and Carlson 1995 | [7] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ktisti, E.; Hatzithomas, L.; Boutsouki, C. Green Advertising on Social Media: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114424

Ktisti E, Hatzithomas L, Boutsouki C. Green Advertising on Social Media: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):14424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114424

Chicago/Turabian StyleKtisti, Evangelia, Leonidas Hatzithomas, and Christina Boutsouki. 2022. "Green Advertising on Social Media: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 14424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114424

APA StyleKtisti, E., Hatzithomas, L., & Boutsouki, C. (2022). Green Advertising on Social Media: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 14(21), 14424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114424