Abstract

Due to the impact of COVID-19, a large number of employees of organizations around the world have been forced to work remotely from home starting in 2020. As a result, leaders and followers face new communication and interaction challenges. If an enterprise is to be successful in the new wave of economic development, it must embrace the role of employee followers. However, there is currently no relevant research. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze the interaction between organic leadership and implicit followers from the perspective of followers who are working remotely and further analyze their relationship with trust in their supervisor, organizational citizenship behavior, and active followership. Using the method of questionnaire measurement, multigroup analysis and ANCOVA and PLS-SEM analysis found the following. First, difference in leadership styles (IV) and implicit followers (IV) had significant effects on employees’ trust in supervisor (DV), organizational citizenship behavior (DV), and active followers (DV). Secondly, the influence of the leaders’ styles (IV) on employees’ trust in supervisor (DV), organizational citizenship behavior (DV), and active followership (DV) was significantly affected only when IFTs were anti-prototypical traits. Finally, organizational citizenship behavior (Med) had an indirect effect between trust in supervisor (DV) and active followership (DV). This article not only fills the gaps in the literature related to leaders and followers, but also provides analytical evidence and new thinking which will enable companies to propose management strategies more effectively for employees working remotely in the face of the impact of the epidemic.

1. Introduction

The spread of the global epidemic has not only brought a series of severe tests to enterprises and their employees, but also completely changed the attitudes of many enterprises. One of the far-reaching impacts is telecommuting, and the cloud office model will become the norm for employees. According to the CALLUP (2022) report, seven in 10 white-collar workers in the United States continue to work remotely [1]. Another Global Workplace Analytics report found that nearly one in ten Swiss job postings allow employees to work from home part of the time, more than three times the rate before the pandemic [2]. In addition, the changing work patterns of Chinese urban populations have also shown a similar trend, catalyzed by the new crown epidemic. In 2005, only about 1.8 million people in the country were working remotely, and by 2019, it has only grown to 5.3 million people. However, since February 2020, nearly 200 million people across the country have started working remotely [3]. In the long run, the epidemic is likely to fundamentally change people’s views on cloud office, change the corresponding matching operating model, and fundamentally reshape the relationship between organizations and employees. This also means that in the future, enterprises need effective leadership to effectively drive the execution of employees to improve the overall performance of the organization [3].

According to Hollander (1978), leadership is composed of leaders, followers, and situations. There is no leader without followers. All leaders are followers at times [4] Hence, leadership effectiveness depends on the level of followers’ willingness. It is the degree to which followers are able and willing to accomplish their job [5]. Kelly (1988) and Chaleff (1995) have also found that an organization’s success is influenced by its followers. Leadership has always been an important topic in the study of organizational leader’s influence on behavior and power [6,7]. Studies have found that leaders’ authority and legal rights alone influence subordinates’ perceptions toward organizational goals. Even though they are binding, they are not sustainable. In addition, the acceptance theory of authority also emphasizes that authority is given by subordinates, and leaders must strive for the understanding, recognition and support of subordinates while being responsible to their superiors [8]. Therefore, it is difficult for a leader to show his leader’s effectiveness without the will and consent of his followers [9]. However, affected by the epidemic, remote home workers no longer face a single leader. The organization in which employees work can be said to be an organic organization with leaderless or multiple leaders. As in the concept of organic leadership proposed by Avery (2004), the reliance of leaders shifts to a non-leader-centric paradigm to reflect changes in the organization and its environment. Organizations are no longer leader-centric and less command and control but instead focus on organizing the collective teamwork of multiple members to achieve a common goal [10].

In practice, it is common for the same supervisor to have different corresponding leadership behaviors for different subordinates; similarly, subordinates will follow different supervisors differently. Many existing studies have explored variable leadership and followership behavior and have also confirmed that leaders and followers have an interactive relationship with each other’s behavior [5,11]. More recent studies have highlighted follower behavior resulting from the interaction between leader and follower behavior [12,13] such as leadership and trust in supervisor [14,15]; leadership and organizational citizenship behavior [16,17]; trust and organizational citizenship behavior [18,19]. Meindl (1995) proposed a follower-centric perspective in his study, which pointed out that leaders and their leadership results are constructed by followers [20]. Subordinates’ perceptions and recognition of their leaders have considerable influence on the results of leaders’ behaviors, or the i.e., subordinates’ views on leaders will determine the relationship between leadership behavior and results. Later, many scholars began to develop research which focused on “follower-based approaches” [12,13,21,22] and began to set the research axis on the followers [23,24].

Since the outbreak of the 2020 epidemic, managing the productivity of employees’ work remotely has become a new challenge for global companies. When the remote work model becomes the future trend, organizations may shift to the organic organization model that Avery proposed in 2004. An organization that allows members to self-manage and self-lead as well as participate in shared decision-making, thereby, the strong leadership tendencies of supervisors have gradually changed into a differentiated management mode based on individual characteristics of employees [25,26]. Avery in 2004 proposed 13 indexes to distinguish organic leadership from the other leadership paradigms, including knowledge bases of high followers (knowledge workers), while remote workers mostly fit this trait [10].

Past literature has related research on leadership and trust in supervisor (TS) [14,19,27]; leadership and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) [16,17,18,19,28]. However, there is no article that integrates these variables to discussing the relationship among interactions of organic leadership (OL) and implicit followership (IFTs), trust in supervisor (TS), active followership (AF), and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Even less focuses on the perspective of followers, as a result, based on the acceptance theory of authority [8] and concept of organic leadership [10], for better understanding the work attitudes of remote workers under the influence of different leaders’ interactions, the purpose of this study was therefore to examine the impact of the interaction of leadership and followership (remote workers) based on followers’ perception (OLIF) on OCB and AF with the mediating role of TS. Understanding this relationship could help to enhance the employee’s OCB and active followership.

The present paper is organized as follows: through literature review and integration in several relevant fields, first, the paper derives research hypotheses and develops a conceptual model. Using the method of questionnaire measurement, multigroup analysis, and through ANCOVA and PLS-SEM analysis, next, all data collected from the target population in China are analyzed. Finally, the findings are presented, followed by conclusions and discussions of the findings including several managerial implications and future research directions. In addition, in order to fill the gap in the previous literature, we will further explore OLIF’s impact on trust in supervisor (TS), organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), and active followership (AF) from the perspective of these followers.

2. Theoretical Foundation and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Interactions of Organic Leadership and Implicit Followership (OLIF)

According to the Barnard’s the acceptance theory of authority, whether an order has authority depends on the recipient of the order, not the issuer of the order. The authority of the leader is not granted by the superior, but from the approval of the subordinate. The superior can only grant you power but cannot give you prestige. This theory emphasizes that: (1) knowledge that cannot be understood cannot be authoritative; (2) if the executor believes that the instruction is inconsistent with the purpose of the organization, the instruction is difficult to be implemented; (3) if an instruction is considered to be harmful to the personal interests of a member of the organization, then the subordinates lack enthusiasm for execution. They will take behaviors such as avoidance, pretending to be sick, superficial coping, and voluntarily resigning; and (4) if an instruction cannot be completed, but reluctantly asks people to execute, the result can only be perfunctory or refusal to execute. Barnard believes that authority granted by superiors is only effective when the subordinates are willing to accept it [8].

Furthermore, the findings of Ehrhart and Klein in 2001, indicated that followers had different responses to the same leader behavior. To enhance employee work engagement and job performance, it becomes very important to identify types of followership so that managers can maximize employee productivity by adopting different leadership styles [29]. Additionally, Bjugstad et al. (2006) proposed an integrated view of the situational leadership theory and followership model. When the leader’s behavior matches with the subordinate’s following pattern, the leader’s effectiveness will become apparent [9]. Zhu et al. (2009) studied the interaction between transformational leadership and following behavior according to the following behavior model proposed by Kelly in 1988. In his research, he found that transformational leadership has different effects on the work contribution of followers with different characteristics [30]. Therefore, the effectiveness of leadership behavior is not only influenced by leadership behavior, but also by deployment behavior. This means, leadership effectiveness is also influenced by the interaction between leaders and followers.

Driven by the remote work-from-home model, the interaction pattern of leaders and followers has changed. Under the virtual network structure, with the influx of knowledge labor, organizations become borderless [31] as an organic organization. As organizations move on a sustainable path in the 21st century and beyond, leadership in teams or networks becomes critical [32]. There is no formal leader in an organic organization, but it is held together by a shared vision, values, and culture of support [26]. Organic leaders in such an organizational culture recognize that everyone has a unique capability and potential. Avery (2004) divides organizational leadership into four leadership paradigms—classical, transactional, visionary, and organic. This style encompasses a variety of leadership forms that have evolved in different locations and over time [10,33]. In addition to this, the leadership style proposed by Avery allows leadership patterns to change with context, respond to organizational requirements and preferences, and reflect many interdependent elements [26]. In addition, unlike traditional leadership paradigms, organic leadership changes traditional understandings of leadership in terms of control, order and hierarchy, trust, acceptance of continuous change, chaos, and respect for different members of the organization [10]. Numerous studies [32,33] support the idea that organizations that employ organic leadership can drive and support organizational growth and corporate sustainability. Moreover, organic leadership is a style of influence that embraces both humanism and compassion. A mix of these leadership attributes primarily includes servant, transformational, and relational leadership style. In terms of leadership, organic leadership is a natural, motivating, compelling, relaxed, inspiring model of hard work, creativity and innovation, and fun [34]. Nohe and Hertel (2017) also found that there is a positive relationship between transformational leadership and organizational citizenship behavior in the analysis of 761 samples [16].

There are 13 indicators proposed by Avery (2004) to distinguish organic leadership from other leadership paradigms, including the following characteristics: autonomous teams; knowledge bases of high followers (knowledge workers); collective power through collaboration; high followership power; consensus decision-making; distributed leadership; low power distance inequality; uncertainty avoidance, individualism, and masculinity; high diversity; adaptability to change; high self-responsibility and committed self-responsibility; network structure; and, applicability to complex and dynamic environments [10]. Jing and Avery (2008) also emphasize that organic organizations do not have a formal leader, and that the interaction of leaders with followers can serve as a form of leadership [26]. In other words, in an organic organization, the interaction between different leaders and followers may produce different follower performance results. As a result, 21st century organizations operate under the complexities of a dynamic environment under the brunt of the pandemic. In the face of informal organizational normative behavior for remote workers, organic leadership has become imperative and critical to the sustainable development of a business.

Furthermore, Avery and Bergsteiner (2011) also proposed that 23 elements can effectively practice sustainable leadership, trust is a high-level practice element, and the practice of sustainable leadership without trust will be affected [33]. Safrizal et al. (2020) linked participatory leadership relationships with performance in a case study of Petrokimia Gresik, focusing on empowerment and trust in supervisors through psychological empowerment, found that participatory leadership style, psychological empowerment, and trust in supervisor will enhance the performance marked by high profits and make the company sustainable [14].

Since an organic organization does not have a formal leader [10,26], the style of leadership can depend on the form of interaction between the leader and followers. This paper selected the four leadership styles (autocratic, democratic, laisses-faire, and transformational) in the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) developed by Bass and Avolio (2004) which is also widely used by researchers [35] to conduct the test of this study and modified the questionnaire to meet the content that the Chinese can understand (see Appendix A). We further investigated the effects of four leader styles on trust in supervisor (TS), organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), and active followership (AF) under the interaction with the implicit followership (IFTs) of remote workers.

2.2. Implicit Followership (IFTs)

Implicit followership is a new concept in the last 20 years. It originates from implicit social cognition theory, which believes that individual experiences will affect judgment and behavior and evolves into a given impression and view of something in the brain [36,37]. Therefore, implicit followership refers to the individual’s expectation of followers’ traits and behaviors, and implicit followership can be further divided into followers’ implicit followership theories, FIFTs [38] and leaders’ implicit followership theories, LIFTs. Implicit followership theory is based on implicit leadership theories (ILTs). Its concept follows the same logic as the formation of cognitive structure. The major difference between the two is the difference of research objects [38]. Implicit leader theory means that followers have specific imaginations about the characteristics and behaviors of ideal leaders. If the leader’s actual leadership style and behaviors conform to the follower’s cognitive prototype (prototype), the follower will be regarded as an effective leader, otherwise, they will be regarded as an ineffective leader [39]; whereas implicit followership theory focuses on the followers and explores the individual’s expectation of the role of followers [38,40].

Previous studies of leadership focused only on the prototype of the leader in the mind of the follower and ignored the cognitive structure related to the prototype of the follower. If the leadership element really exists in the follower’s brain, we should be more able to understand the views and ideas of the follower [38,40]. Sy (2010) also points out that the leader’s internal cognition of followers will not only have various influences on the interpersonal relationship between them, but also have the results beyond interpersonal relationship at some times. That is, it will affect the followers’ organizational citizenship behavior, which will promote or reduce the followers’ motivation and behavior for organizational efforts [40].

2.3. Trust in Supervisor (TS)

A three-year survey of 7500 workers was implemented to understand the impact of the trust in their leader by Froggatt in 2001 [41]. The study found that employees who show high levels of trust in their supervisor had a 108 percent three-year return to shareholders. According to Hosmer (1995), trust is an individual’s optimistic expectation about the outcome of an event [42]. Rotter (1967) proposed that interpersonal trust is “An expectancy helps by an individual or a group that the word, promise, verbal or written statement of another individual or group can be relied upon” [43]. According to the Academy of Management Review, the most common definition of interpersonal trust was proposed by Mayer et al., (1995) as “the willingness of a subordinate to be vulnerable to the actions of his or her supervisor whose behavior and actions he or she cannot control” [44]. The present study defined the trust in supervisor according to McAllister (1995) who proposed two-dimensional principal forms of interpersonal trust: cognition-based trust (grounded in individual beliefs about peer reliability and dependability) and affect-based trust (grounded in reciprocated interpersonal care and concern) [45].

In recent years, there have been many studies on the effectiveness of work execution in terms of employee trust. They included trust in supervisor [19,46,47], trust in top management [46,48], and interpersonal trust [44,45]. Many studies have verified that trust in work, especially between leaders and subordinates, has a direct impact on OCB [19]. For example, Jin and Hahm (2017) conducted a study on 165 employees of State-Owned Enterprises in China and found that when subordinates have higher trust in leaders, the organizational citizenship behavior of subordinates will be improved [19].

2.4. Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

Based on Katz’s (1946) category of out-of-role behavior [49], Organ (1988) developed the concept of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), who defined OCB as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” [50] (p.4). According to the definitions of OCB by different researchers, organizational citizenship behavior focuses on the behavior outside the role defined by the organization. Work performance and attitude of members in the organization will directly affect the achievement of work performance and organizational goals. Without the influence of the organization’s reward system, employees can show their own informal contributions, rather than the behaviors and attitudes that come from the rules or contracts set by the organization. OCB can be an individual’s spontaneous extra contribution behavior in addition to the organization’s work requirements, and it can help the organization’s growth [50,51,52,53].

In addition, the study results by Posdakoff and Mackenzie (1994) show that OCB has a significant influence on the performance of task objectives [51]. The research of Podsakoff et al. (2000) proposed four antecedents of OCB individual characteristics, task characteristics, organizational characteristics, and leadership behavior [52]. Many studies have considered leadership behavior as an antecedent of OCB; however, the finding of these studies still lack consistency. Some of studies indicated that leadership behavior and the relationship between leader and subordinate may have positive [17,18,52,54,55]. However, Bilgin et al. (2015) found no direct or indirect relationship between charismatic leadership (CL) and OCB in their study on OCB in the Turkish hospitality industry [56]. As a result, this study believes that different leadership styles may lead to different behaviors of subordinates. Thus, our study aims to redress this gap by investigating the relationship among interaction of leadership and followership, implicit followership, trust in supervisor and organizational citizenship behavior.

2.5. Active Followership (AF)

In the past three decades, many scholars have verified that leadership has an impact on organizational effectiveness and employees’ work outcomes [17,24,57]. However, many scholars began to question how the leader’s leadership effectiveness can be demonstrated without the participation and contribution of followers. Leadership necessarily requires followership. Without followers and the behaviors of following there is no leadership. This means the behavior of followers is crucial to the leadership process [6,9,20,22,58,59,60].

Although many scholars began to explore the influence of follower from the theoretical framework and perspective of followers, the concept and definition of active followership are still not clear. In the past, followers in the organization were regarded to have a passive role, obeying, and executing the leader’s orders. However, with the research and confirmation that followership has an impact on leadership and organizational effectiveness, the followship is given a positive image [61,62,63]. According to Chaleff (1995), followership as an active process, followers are participants, collaborators, and co-leaders to achieve organizational goals. He proposed the five characteristics of followers: the courage to assume responsibility, the courage to serve, the courage to challenge, the courage to participate in transformation, and the courage to leave [7]. Therefore, we can say that there are two paradigms in the expression of followership: passive followership and active followership. Different followership paradigms should have different effects on leadership effectiveness. As there are few studies involving active followers in the current research literature, this study will use the questionnaire developed by Liu et al. (2016), which contains four dimensions: support for leader, interaction with leader, enterprise, and loyalty. These four dimensions mainly refer to positive psychology, behavior, and relationship characteristics of successful and effective followers in the process of striving to achieve the common positive goals with the leaders. These dimensions are defined from the perspective of Chinese people, combined with the views of western scholars on active followership [60].

2.6. The Relationship among OLIF, Trust in Supervisor, OCB, and Active Followership

In recent decades, many scholars have focused on the research of leadership. However, many scholars also proposed that followers are a very important factor in the effectiveness of leadership. In the relevant research on the interaction between leadership and followership, there have been studies to explore the relationship between leadership styles and followers’ characteristics [12,13]; leader and follower interactions; the relations with OCB and sales productivity [24]; about how the interaction between transformational leadership and followers affects the engagement contribution of subordinates [64].

The influence of trust in both leaders and subordinates has a direct or indirect impact on organizational behavior outcomes which has been recognized in many studies. It has included organizational citizenship behavior, work engagement, and job performance. In most studies, the factor of trust played a role in mediating or moderating behavior [15,19,27,46,47]. Jin and Hahm (2017) found that trust in supervisor plays the mediating role in the relationship between ability, fairness, and integrity, and OCB [19]. Huang et al. (2021) conducted a study of nurses working in hospitals in China and found that perceived ethical leadership has a significant indirect impact on organizational citizenship behavior through trust in management and psychological well-being [47]. In addition, Bhatti, et al., (2019) found in a study of employees working in hotels in Pakistan, that affective trust has a significant mediating effect on the relationship between participatory leadership and organizational citizenship behavior [65]. In Moon’s (2019) study, trust in the manager had significant direct and indirect relationships with employees’ feedback acceptance and job satisfaction [46].

However, the literature on the relationship between active followership (AF) and other organizational behaviors is too little and too old. In addition, based on the concept of implicit followership (IFTs), if the leader’s style does not match the follower’s cognitive prototype, they are considered an invalid leader, but do they have an impact on leadership styles and TS, OCB, and AF? In addition, according to the literature review, trust in supervisor (TS) does have an improving effect on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) [19], and OCB is a behavioral result of followers being influenced by leaders [17,52,54], as a result, this paper hypothesizes that OCB may have a mediating effect on the relationship between TS and AF.

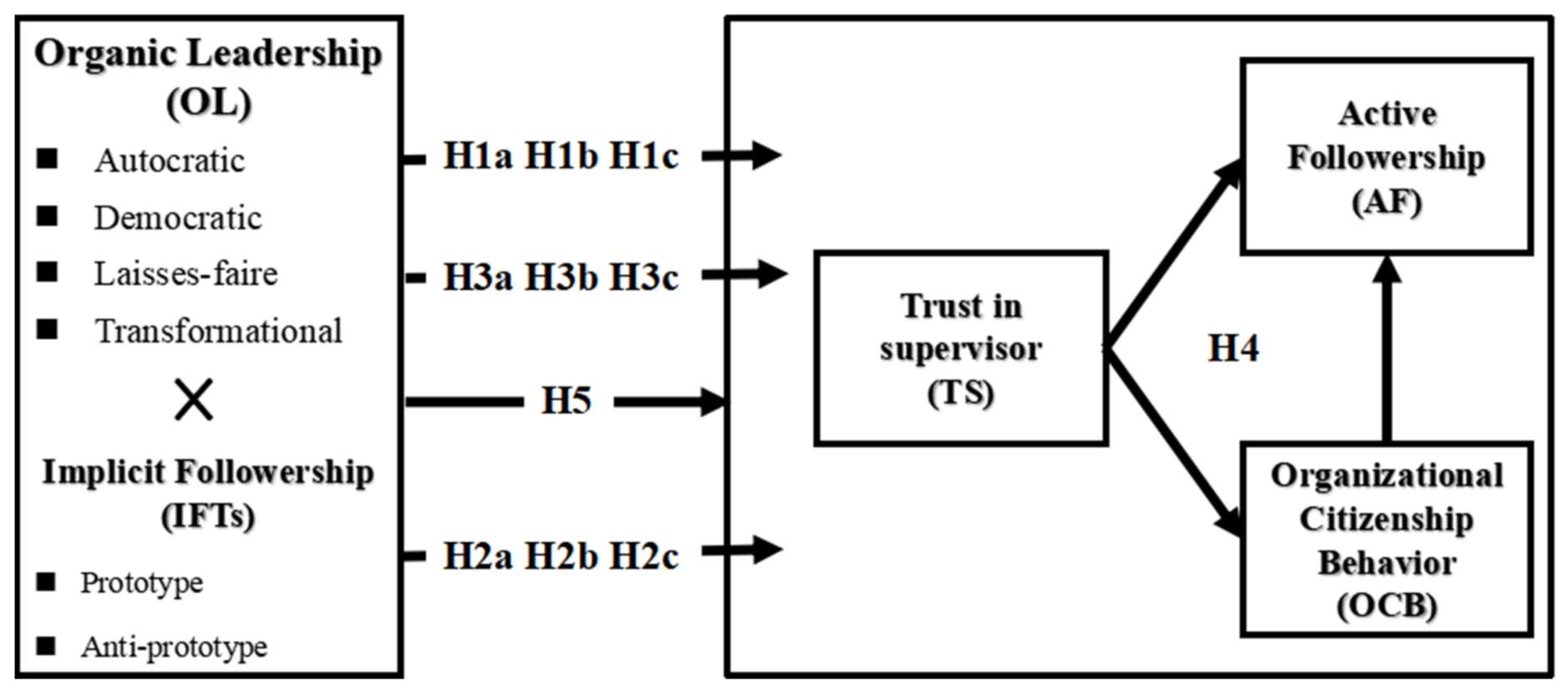

In conclusion, in order to further confirm the relationship between these variables (OL IF, TS, OCB, and AF) this study hopes to investigate employees working from home, to explore whether they have different following behaviors when faced with different leadership styles. In terms of practical contribution, for these work from home employees, we hope to provide this research result so that leaders and followers can interact more effectively to achieve organizational performance. As a result, the conceptual model summarizing of this study hypotheses are depicted in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

The Impact Model of Interaction of Leadership and Followership (ILIF).

H1a:

Different leaders’ styles (IV) have significant differences in the impact of employees’ TS (DV).

H1b:

Different leaders’ styles (IV) have significant differences in the impact of employees’ OCB (DV).

H1c:

Different leaders’ styles (IV) have significant differences in the impact of employees’ AF (DV).

H2a:

Different implicit followership (IFTs) (IV) has significant differences in the impact of employees’ TS (DV).

H2b:

Different IFTs (IV) have significant differences in the impact of employees’ OCB (DV).

H2c:

Different IFTs (IV) have significant differences in the impact of employees’ AF (DV).

H3a:

The influence of theleaders’ styles (IV) on employees’ TS (DV) is significantly affected by the difference in IFTs (Moderator/Mod).

H3b:

The influence of theleaders’ styles (IV) on employees’ OCB (DV) is significantly affected by the difference in IFTs (Mod).

H3c:

The influence of theleaders’ styles (IV) on employees’ AF (DV) is significantly affected by the difference in IFTs (Mod).

H4:

OCB (Med) has a mediating effect between TS (IV) and AF (DV).

H5:

The different OLIF (Mod) will significantly affect the mediating effect of OCB (Med) between TS (IV) and AF (DV).

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Participants

A total of 74 items and 10 personal data items were used to evaluate all factors of this study. All variables were measured using scales adapted from existing scales. They are the most widely used questionnaires in related research today (see Appendix A). Related reference sources are shown in Table 1 below; the measurement method is based on the Likert scale. According to 52 prediction questionnaires, the predicted Cronbach α value of each variable is greater than 0.5 (see Table 1), which basically has good internal consistency [66].

Table 1.

Measurement instruments.

In this study, the online convenience sampling approach was used to distribute the questionnaires. The questionnaires were placed on the Questionnaire Star platform (https://www.wjx.cn/ accessed on 5 September 2021) and were widely distributed to people who had switched to remote work from home due to the epidemic. At the same time, related questions were also designed in the questionnaire to confirm whether the subjects were working from home. Furthermore, in terms of the number of questionnaires required Bentler and Chou (1987) recommend that the ratio of sample size to number of free parameters be 5:1 [67]. The first 37 items of the questionnaire in this study are used to distinguish the types of OL and IFTs of the subjects and to be used as categorical variables (independent variables). The dependent variables involved in the subsequent statistical analysis are TS, OCB, and AF. There are 58 free parameters, as the result, the number of valid samples required for this study should be between 290–580; as a total of 472 samples were recovered in this study, of which 360 were valid (the effective rate was 72.27%), which met the research needs.

The demographic characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 2. This study uses demographic variables such as gender, age, education level, income, and working qualifications to understand whether different groups will cause the relationship between these variables. However, it has not been found that demographic variables have significantly different effects on the relationship between these variables.

Table 2.

The demographic characteristics of the subjects.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Multigroup Analysis

The aim of this study was to understand the effects of different types of OL and IFTs on TS, OCB and AF, so a multigroup analysis was used for the study. The respondents were classified according to the filling results of OL and IFTs in the questionnaire.

In the research framework, there are four groups of Leader styles and two groups of Implicit Followership that need to be clearly classified, manipulated, and checked.

In the research, the tests classify the average number of answers of each type of Leaders styles and use the paired sample T test to perform the manipulation check. According to the results of data analysis: Autocratic leadership characteristics, the average number of Autocratic responses is significantly higher than the average number of responses for Democratic, Laisses-faire, and Transformational (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Multigroup analysis.

The same results were also obtained for the three types of leaders of Democratic, Laisses-faire, and Transformational, all of which have higher average answers than other types. Therefore, this study can basically confirm that the Leaders Trait of 360 subjects can be divided into four categories: Autocratic (N = 93), Democratic (N = 90), Laisses-faire (N = 85), and Transformational (N = 92) (see Table 3).

In addition, the classification of Implicit Followership is conducted using the same manipulation check method. The analysis results also show that the average number of prototype responses is significantly higher than that of anti-prototype subjects (see Table 3).

As for anti-prototype subjects, the average answer of anti-prototype is also significantly higher than that of prototype subjects. Therefore, it can be basically confirmed that the Implicit Followership of the subjects participating in this study can be divided into Prototype (N = 175) and Anti-prototype (N = 185) (see Table 3).

3.2.2. Direct and Interaction Effect Testing

Two-Way ANCOVA

In this study, a 4 × 2 two-way ANCOVA was used to preliminarily test the influence of Organic Leaders Style (OL) and Implicit Followership (IFTs) on TS, OCB and AF. The analysis results are shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Two-way ANCOVA test results.

Through the analysis of the results, it was found that different types of Leaders Trait will have significant differences in TS, OCB, and AF; different types of Implicit Followership will also have significant differences in TS, OCB, and AF. Moreover, the impact of different types of organic leaders (OL) on OCB and AF will be adjusted by Implicit Followership and will have significant differences (see Table 4).

Based on the above analysis results, this study further analyzes the influence of Leaders Style and Implicit Followership on the main effects and interactions of TS, OCB and AF through the independent sample T test and interaction diagrams, and gradually verifies whether the hypothesis is true.

Direct Effect Testing

It can be seen from Table 5 that the types of Leaders Trait have significant differences in the impact of TS, OCB, and AF. First of all, in terms of the impact on TS, Auto-cratic type subjects have significantly less TS than Democratic (MAutocratic = 2.986, MDemo-cratic = 3.857, T = −7.271, p < 0.05) and Transformational (MAutocratic = 2.986, MTransformational = 3.767, T = −6.373, p < 0.05) type; Democratic type subjects have significantly higher TS than Laisses-faire (MDemocratic = 3.857, MLaisses-faire = 2.919, T = 7.557, p < 0.05) type; Laisses-faire type subjects Its TS is significantly smaller than Transformational (MLaisses-faire = 2.919, MTransformational = 3.767, T = −6.674, p < 0.05) type. Therefore, H1a is supported.

Table 5.

Direct effect of Leaders Trait.

Furthermore, for the impact on OCB, the OCB of Autocratic type subjects was sig-nificantly smaller than that of Democratic type (MAutocratic = 5.128, MDemocratic = 5.483, T = −2.814, p < 0.05) and Transformational type (MAutocratic = 2.986, MTransformational = 5.464), T = −2.694, p < 0.05). Therefore, H1b is supported.

Finally, for the impact on AF, Autocratic type subjects have significantly less AF than Democratic (MAutocratic = 3.233, MDemocratic = 3.601, T = −3.779, p < 0.05) and Transfor-mational types (MAutocratic = 3.233, MTransformational = 3.625, T = −4.001, p < 0.05); Democratic type subjects have significantly greater AF than Laisses-faire type (MDemocratic = 3.601, MLaisses-faire = 3.374, T = 2.445, p < 0.05); Laisses-faire type subjects Its AF is significantly smaller than the Transformational type (MLaisses-faire = 3.374, MTransformational = 3.625, T = −2.668, p < 0.05). Therefore, H1c is supported (see Table 5).

From Table 6, that different types of Implicit Followership have a significant impact on TS, OCB, and AF. Furthermore, for the impact on TS, OCB, and AF, this study further found that Prototype followers are either in the TS (MPrototype = 3.698, MAnti-prototype = 3.093; T = 6.518, p < 0.05), OCB (MPrototype = 5.722, MAnti-prototype = 4.997; T = 9.744, p < 0.05) or AF (MPrototype = 3.820, MAnti-prototype = 3.117; T = 11.955, p < 0.05) are significantly better than those of Anti-prototype followers. According to above, H2a, H2b, and H2c are supported.

Table 6.

Direct effect of Implicit Followership.

Interaction Effect Testing

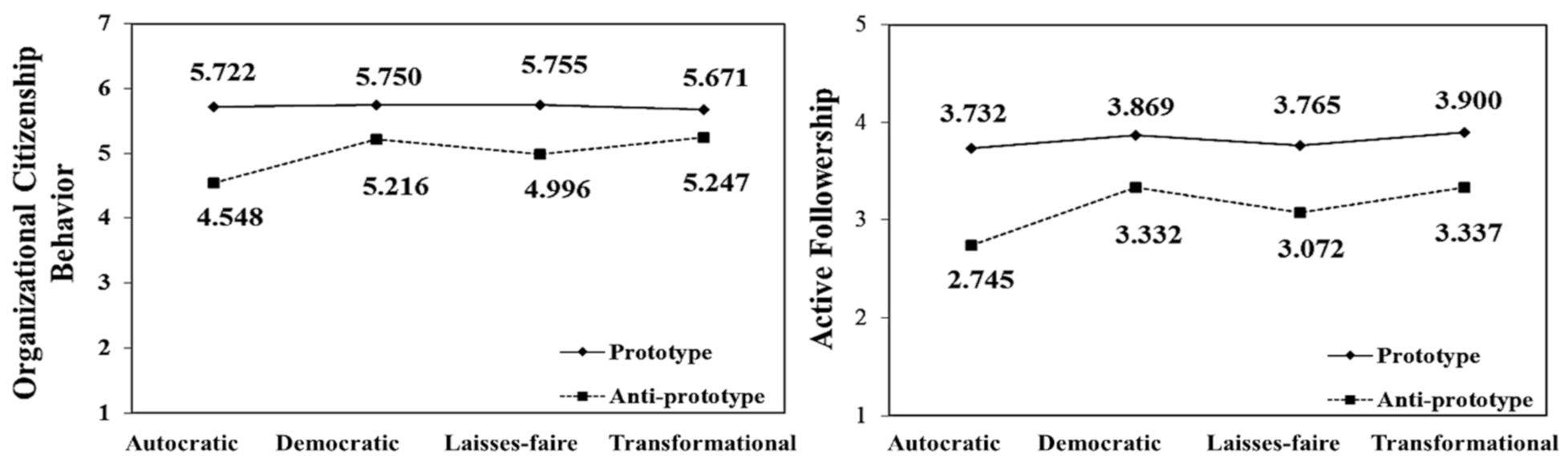

Through the two-way ANCOVA test results, it is known that under the interaction of OL and IFTs, the impact on TS (F = 1.634, p = 0.181) is not significantly different, but there is a difference in the impact on OCB (F = 5.467, p = 0.001) and AF (F = 3.477, p = 0.016) (see Table 4). Further through the comparison of cell mean and the interaction diagram, we can know: Regarding the influence on the followers of different IFTs, the influence of OL on the OCB and AF, Prototype followers will be significantly better than Anti-prototype followers; and the difference in the impact of OL on OCB and AF does not exist for Prototype followers, but it will have a significant impact on Anti-prototype followers. From this result, we can infer that Prototype’s followers have high spontaneous behaviors, whether in organizational citizenship behavior or in following behaviors expected by the leader, as a result, H3a is not supported.

The influence of OL on OCB when IFTs are anti-prototype traits, under Autocratic leadership style, its influence on OCB will be significantly less than Democratic (MAuto-cratic = 4.548, MDemocratic = 5.216; T = −3.750, p < 0.05), Laisses-faire (MAutocratic = 4.548, MLaisses-faire = 4.996; T = −2.477, p < 0.05), and Transformational (MAutocratic = 4.548, MTransfor-mational = 5.247; T = −3.926, p < 0.05); H3b is supported.

Furthermore, the influence of OL on AF, the influence of Autocratic leadershipstyles on Anti-prototype followers was significantly less than that of Democratic leadershipstyles (MAutocratic = 2.745, MDemocratic = 3.332; T = −5.322, p < 0.05), Laisses-faire (MAutocratic = 2.745, MLaisses-faire = 3.072; T = −2.796, p < 0.05) and Transformational (MAutocratic = 2.745, MTransformational = 3.337; T = −3.332, p < 0.05); and Laisses-faire is also significantly smaller than Democratic (MLaisses-fair = 3.072, MDemocratic = 3.337; T = −2.366, p < 0.05) and Transformational (MLaisses-fair = 3.072, MDemocratic = 3.337; T = 2.335, p < 0.05), as result, H3c is supported. (see Table 7 and Figure 2).

Table 7.

The cell means for the TS, OCB and AF—Two factors.

Figure 2.

Interaction effect between OL.

3.2.3. Meditating Effects Testing of PLS-SEM

Reliability, Validity

In this study, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) shows that the factor loading of each variable measurement factor in the study is greater than 0.5; and the Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (ρc) of each variable also meet the requirements, showing good internal consistency as a whole [68,69,70]. As a result, the reliability is qualified.

In addition, in terms of validity, through the verification of Factor loading (greater than 0.5), composite reliability (greater than 0.6), and AVE (greater than 0.5), all the data meet the requirements, showing that each research variable has construct validity. Furthermore, according to the discriminant validity analysis, the Fornell–Larcker criterion, (discriminant validity is given when the shared variance among any two constructs is less than the AVE of each construct) can also identify clear differences between the research variables [68,69,70]. These results imply that all constructs complied with the requirement [68,69,70]. The relevant data are shown in Table 8 and Table 9:

Table 8.

Measurement model assessment.

Table 9.

Discriminant Validity: Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

Meditating Effects of OCB

Through PLS-SEM, this study analyzes the causal relationship between TS, OCB, and AF, and explores the mediating effect of OCB between TS and AF (see Table 10). Based on the Full model, TS has a significant positive effect on AF, OCB and OCB on AF direct effects, and the indirect effect between TS and AF is significant; the intermediary effect of OCB exists, and it is partial mediation. As a result, H4 is supported.

Table 10.

Testing of the mediating effect.

Multigroup Analysis and Meditating Effect Comparison

Furthermore, this study further uses Multigroup analysis to analyze whether the mediation effect of OCB is significantly different between the prototype model and the anti-prototype model. The analysis results of the two models show that the direct and indirect effects of the two models are both significant (see Table 10). At the same time, through the analysis of the multigroup comparisons approach [71,72], there is no significant difference between the two models, whether it is Direct Effects (Coefficient Differenc = 0.084, T = 0.914, p = 0.362), Indirect Effects (Coefficient Differenc = 0.015, T = 0.263, p = 0.793) or Total Effects (Coefficient Differenc = 0.066, T = 0.673, p = 0.501). There is no significant difference in the intermediary effect of OCB between TS and AF. As a result, H5 is not supported.

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

In theoretical implications, based on the principle of organic leadership (OL), the so-called OL is a leadership form without a specific leadership style, and the performance of followers depends on the results of interactions with different leaders [10,26]. Furthermore, according to the authoritative acceptance theory, whether an instruction is authoritative depends on the recipient of the instruction, not the issuer of the instruction. The results of this study formally verify these ideas [8]. Interestingly, however, this study also found that that if the implicit followership self-perception of the followers belongs to the prototype, then regardless of the leader type, the follower’s OCB or AF spontaneous behavior performance is higher. Conversely, the follower’s implicit followership self-perception belongs to the anti-prototype, and the results of the follower’s OCB and AF will vary according to the leadership style (see Figure 2). Does this also mean that the leader has a certain influence on the behavior of followers, but the influence of the latter on OCB and AF is stronger than the influence of leadership style compared with the followers’ own perception of followership? Such an inference deserves the attention of researchers, and more verification results are proposed.

From an academic point of view, this research model provides a different behavioral perspective–the perspective of followers. Today, leaders are no longer the main stakeholders in organizational performance. More organizations expect effective follow-up results rather than leadership processes. The management concept that focused on leadership effectiveness in the past seems to need change. However, follower research seems to receive less attention than leader related research. Previous studies on leadership only focused on the leader prototype in the mind of the follower and ignored the cognitive structure related to the follower prototype. This result is insufficient as a reference application for employee management. Therefore, this article fills up the gaps in the literature on the cognitive influence and interrelationship of TS, IFTs, AF, and OCB for followers.

4.2. Practical Implications

As the epidemic has changed the working model of the entire workplace, research on remote workers is relatively important. There is currently not much research on follower behavior and implicit following, and there is no literature on the relationship between organic leadership and remote workers. Since remote workers do not have direct contact with leaders, their spontaneity has a relatively more direct impact on work behavior and attitudes, which in turn is more reflected in job performance.

In view of the findings in the study, if the implicit followership of followers’ self-perception belongs to the prototype, no matter what leadership type they encounter, they will have higher OCB and AF performance. Therefore, how to recruit and cultivate a positive and committed employee seems to be more important if the business wants them to work remotely. At the same time, leaders must adjust their leadership style appropriately in the face of different followers to help subordinates have better work performance and achieve organizational goals together. Companies should also regularly provide relevant training to improve leadership effectiveness to assist leaders in changing their leadership style in response to changes in the workplace environment

This study explored the perspective of followers, providing new ideas for organizations and managers. In the future, organizations need to pay more attention to remote workers. Companies also need to be more open, accept new mainstream concepts, i.e., more understanding and attention to the ideas and behaviors of the new generation of employees.

4.3. Limitations and Future Direction

Although there are some findings in this study, however, due to the impact of the epidemic in China, it is not possible to directly contact the respondents. Therefore, one of our limitations is that our data uses a snowball technique. The data generated by this technique may violate many assumptions in probability statistics [73].

At the same time, because of the epidemic, most of the workers from other countries who worked in China have been evacuated, and there are not many foreign workers that can be reached by the investigation. Therefore, when the epidemic is over in the future, in order to understand the behavior of followers more effectively, researchers can use other methods of questionnaire collection in the future to investigate remote workers from different nationalities and industries. In addition, the content, and dimensions of employees’ implicit following need to be further improved. Future research can explore the connotation and methods of different employees’ following behaviors, and continuously expand the depth and breadth of the construction.

The role of the follower in the organization cannot be ignored. Follower motivation, their characteristics and the relationship between the follower and the leader, directly or indirectly, affect the operation of the organization. Therefore, how to cultivate a follower with good following traits and the establishment of a stable and open two-way relationship between followers and leaders will be the focus of future research and help to achieve the self-improvement of followers and leaders and organizational sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-W.L.; Data curation, M.-T.H.; Methodology, M.-T.H.; Writing—original draft, S.-W.L. and R.N.; Writing—review & editing, R.N. and H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Screening questions

Are you currently requesting or being asked by the company to work remotely from home due to the epidemic?

□ Yes (continue to answer) □ No (end answering)

Demographic characteristics

- 1.

- Gender:

(1) Male (2) Female

- 2.

- Age:

(1) Under 20 years old (2) 20–30 years old (including 20 years old) (3) 31–40 years old (4) 41–50 years old (5) 51–60 years old (6) Over 61 years old

- 3.

- Education:

(1) High school or below (2) High school (3) College (4) Master (5) Doctor

- 4.

- Monthly income:

(1) Below 30,000 (2) 30,001~40,000 (3) 40,001~50,000 (4) 50,001~60,000 (5) Above 60,001

- 5.

- Years of service (from the beginning of work; in years):

(1) Less than 1 year (2) 1 year to 2 years (3) 2 years to 3 years (4) 3 years to 4 years (5) 4 years to 5 years (6) More than 5 years

- 6.

- Experience in the current company:

(1) Less than 1 year (2) 1 year to 2 years (3) 2 years to 3 years (4) 3 years to 4 years (5) 4 years to 5 years (6) More than 5 years

- 7.

- Gender of my supervisor:

(1) Male (2) Female

- 8.

- Educational background of my supervisor:

(1) High school or below (2) High school (3) Junior college (4) Master (5) Doctor

- 9.

- My current industry:

(1) Business related (2) Medical related (3) Manufacturing related (4) Tourism related (5) Education related (6) Related to retail store sales and online sales (7) Catering service related (8) High (Technology) Related (9) Military police or public units (10) Others 10.

- 10.

- My time with my supervisor:

(1) Less than 1 year (2) 1 year to 2 years (3) 2~3 years (4) 3~4 years (5) 4~5 years (6) More than 5 years

Leader Style

The evaluation and judgment criteria are as follows: 1 → 5 indicates that the degree is from “very disagree” to “very agree”.

| Autocratic |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Democratic |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Laisses-Faire |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Transformational |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Implicit Followership Scale, (IFTs)

1–9 is the positive prototype followship, 10–18 is the anti-prototype followship.

The evaluation and judgment criteria are as follows: 1 → 6 indicates that the degree is from “very inconsistent” to “very consistent”.

| prototype |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Anti-prototype |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Trust in Supervisor

The evaluation and judgment criteria are as follows: 1 → 5 indicates that the degree is from “very disagree” to “very agree”.

| Cognitive trust in supervisor |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Affective trust in supervisor |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

The evaluation and judgment criteria are as follows: 1 → 7 indicates that the degree is from “very disagree” to “very agree”.

| Altruism |

|

| |

| |

| Courtesy |

|

| |

| |

| Civic Virtue |

|

| |

| |

| Conscientiousness |

|

| |

| |

| Sportsmanship |

|

| |

|

Active Followership

The evaluation and judgment criteria are as follows: 1 → 5 indicates that the degree is from “very disagree” to “very agree”.

| Support for leader |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Interaction with leader |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Enterprise |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| Loyalty |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

References

- CALLUP. Seven in 10 U.S. White-Collar Workers Still Working Remotely. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/348743/seven-u.s.-white-collar-workers-still-working-remotely.aspx (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Swissinfo.ch. Nearly 1 in 10 Swiss Job Postings Allow Working from Home. Available online: https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/home-office-option-offered-in-almost-every-tenth-swiss-job-ad/47443770 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Xinhua Finance. OCN: Remote Office Data Analysis—The Rise and Development of the Remote Office Industry against the Background of the Epidemic in April 2020. Available online: https://www.cnfin.com/news-xh08/a/20200430/1934160.shtml (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Hollander, E.P. Leadership Dynamics; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R.E. In praise of followers. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1988, 66, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chaleff, I. The Courageous Follower: Standing up to and for Our Leaders; Barrett-Koehler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, C.I. The Functions of the Executive, Cambridge; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Bjugstad, K.; Thach, E.; Thompson, K.; Morris, A. A fresh look at followership: A model for matching followership and leadership styles. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2006, 7, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C. Understanding Leadership; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Riggio, R.E.; Lowe, K.B.; Carsten, M.K. Followership theory: A review and research agenda. Leadersh. Q. 2014, 25, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Zou, W.Q.; Liu, N.T. Leader Humility and Machiavellianism: Investigating the Effects on Followers’ Self-Interested and Prosocial Behaviors. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 742546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. Analysis of Researches on Implicit Followership Theories in Organization and Future Prospects. Adv. Psychol. 2019, 9, 1260–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safrizal, H.B.A.; Eliyana, A.; Firdaus, M.; Rachmawati, P.D. The Effect of Participatory Leadership on Performance through Psychological Empowerment and Trust-in Supervisor. Sys. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Maximo, N.; Stander, M.W.; Coxen, L. Authentic leadership and work engagement: The indirect effects of psychological safety and trust in supervisors. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2019, 45, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohe, C.; Hertel, G. Transformational Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Test of Underlying Mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartey-Baah, K.; Anlesinya, A.; Lamptey, Y. Leadership behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of job involvement. Int. J. Bus. 2019, 24, 1083–4346. [Google Scholar]

- Tourigny, L.; Han, J.; Baba, V.V.; Pan, Y. Ethical Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: A Multilevel Study of Their Effects on Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Hahm, S.W. The effect of employee’s perception of supervisor’s characteristics on organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating role of trust in supervisor. Int. Inf. Inst. 2017, 7, 5143–5152. [Google Scholar]

- Meindl, J.R. The romance of leadership as a follower-centric theory: A social constructionist approach. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graen, G.B.; Uhl-Bien, M. Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Pillai, R. The Romance of Leadership and The Social Construction of Followership. In Follower-Centered Perspectives on Leadership: A Tribute to the Memory of James R. Meindl; Shamir, B., Pillai, R., Blight, M., Uhi-Bien, M., Eds.; PLS: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2009; pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Keck, N.; Giessner, S.R.; Quaquebeke, N.V.; Kruijff, E. When do followers perceive their leaders as ethical? A relational model’s perspective of normatively appropriate conduct. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 164, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Jimmieson, N. Leader-Follower interactions: Relations with OCB and sales productivity. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raelin, J.A. We the Leaders: In Order to Form a Leaderful Organization. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2005, 12, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Avery, G. Missing Links in Understanding The Relationship between Leadership And Organizational Performance. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2008, 7, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Taştan, S.B.; Davoudi, S.M.M. An examination of the relationship between leader-member exchange and innovative work behavior with the moderating role of trust in leader: A study in the Turkish context. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 181, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikand, R.; Ma, S. Sustainable Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behaviour: Exploring Mediating Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Bus. Perspect. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, M.G.; Klein, K.J. Predicting followers’ preferences for charismatic leadership: The influence of follower values and personality. Leadersh. Q. 2001, 12, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Avolio, B.J.; Walumbwa, F.O. Moderating role of follower characteristics with transformational leadership and follower work engagement. Group Organ. Manag. 2009, 34, 590–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantabutra, S.; Suriyankiekaew, S. Examining Relationships Between Organic Leadership And Corporate Sustainability: A Proposed Model. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2012, 28, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, C.C.; Pearce, C.L.; Sims, H.P., Jr. The Ins and Outs of Leading Teams: An Overview. Organ. Dyn. 2009, 38, 179–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable leadership practices for enhancing business resilience and performance. Strategy Lead. 2011, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D. Organic Leadership and Mentoring. Available online: https://talentc.ca/2015/organic-leadership-and-mentoring/ (accessed on 2 October 2022).

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. MLQ: Multifactor Questionnaire: Third Edition Manual Sampler Set; Mind Garden: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Banaji, M.R. Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 2, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Maher, K.J. Leadership and Information Processing: Linking Perceptions and Performance; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, M.K.; Uhl-Bien, M.; West, B.J.; Patera, J.L.; McGregor, R. Exploring social constructions of followership: A qualitative study. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 2, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, R.G.; Foti, R.J.; De Vader, C.L. A test of leadership categorization theory: Internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1984, 34, 343–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, T. What do you think of followers? Examining the content, structure, and consequences of implicit followership theories. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2010, 113, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froggatt, C.C. Work Naked; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, L.T. Trust: The connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J. Personal. 1967, 35, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D. J Affect and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K. Specificity of performance appraisal feedback, trust in manager, and job attitudes: A serial mediation model. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, e7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Qiu, S.; Yang, S.; Deng, R. Ethical Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediation of Trust and Psychological Well-Being. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.P.; Kuhnert, K.W. A theoretical Review and Empirical Investigation of Employee Trust in Management. Public Adm. Q. 1992, 16, 265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D. The interpretation of survey findings. J. Soc. Issues 1946, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors and Sales Unit Effectiveness. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 351–363. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; YU, E.; Chu, X.; Li, Y.; Amin, K. Humble Leadership Affects Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Sequential Mediating Effect of Strengths Use and Job Crafting. Organ. Psychol. 2020, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, A.; Mezginejad, S.; Taherpour, F. The Role of Leadership Styles in Organizational Citizenship Behavior through the Mediation of Perceived organizational Support and Job satisfaction. Innovar 2020, 30, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, N.; Kuzey, C.; Torlak, G.; Uyar, A. An investigation of antecedents of organizational citizenship behavior in the Turkish hospitality industry: A structural equation approach. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2015, 9, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, L.M.; Gooty, J.; Williams, M. The role of leader emotion management in leader-member exchange and follower outcome. Leadersh. Q. 2016, 27, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burak, O.C.; Bashshur, M.R. Followership, leadership, and social influence. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 919–934. [Google Scholar]

- Foti, R.J.; Hansbrough, T.K.; Epittopaki, O.; Coyle, P.T. Dynamic viewpoints on implicit leadership and followership theories: Approaches, findings, and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Peng, J.; Lu, H. Active followership: Conceptualization, content structure, scale development, and rash model analysis. J. Northwest Norm. Univ. 2016, 53, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, T. Followership in athletics why follower-centric spaces perform better. Ind. Commer. Train. 2021, 53, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegbeleye, I.D.; Kaufman, E.K. Relationship Between Middle Managers’ Transformational Leadership and Effective Followership Behaviors in Organizations. J. Leadersh. Stud. 2020, 13, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzolek, D.C. Effective and Engaged Followership: Assessing Student Participation in Ensembles. Music Educ. J. 2020, 3, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Cox, J.; Sims, H.P. The forgotten follower: A contingency model of leadership and follower self-leadership. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.H.; Ju, Y.; Akram, U.; Bhatti, M.H.; Akram, Z.; Bilai, M. Impact of Participative Leadership on Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Mediating Role of Trust and Moderating Role of Continuance Commitment: Evidence from the Pakistan Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortzel, L. Multivariate Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Chou, C.P. Practical Issues in Structural Modeling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1987, 16, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Tatham, R.L.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Macmillan Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C. National customer satisfaction barometer: The Swedish experience. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. A new and simple approach to multi-group analysis in partial least squares path modeling. In Causalities Explored by Indirect Observation: Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on PLS and Related Methods (PLS’07); Martens, H., Næs, T., Eds.; PLS: Matforsk, Ås, Norway, 2007; pp. 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M. Multigroup analysis in partial least squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. Adv. Int. Mark. 2011, 10, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Science Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).