Living on the Edge: Comparing the Quality of Life Transformation of Local Communities Induced by New Town Development in Different Peri-Urban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Evolvement of Peri-Urban Areas in Developing Countries

2.2. New Town Development: Solutions for Providing New Urban Activities in Peri-Urban Areas

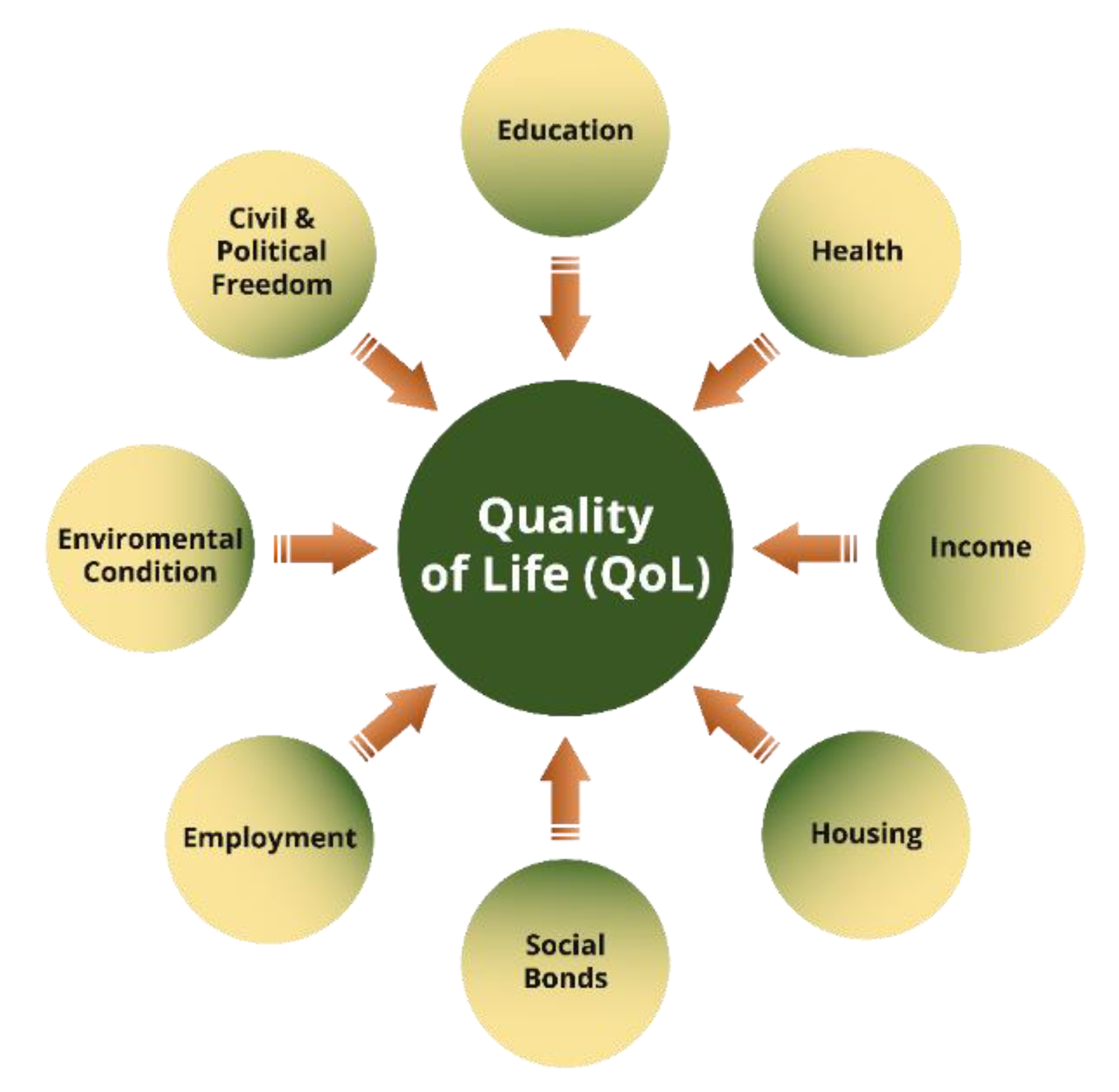

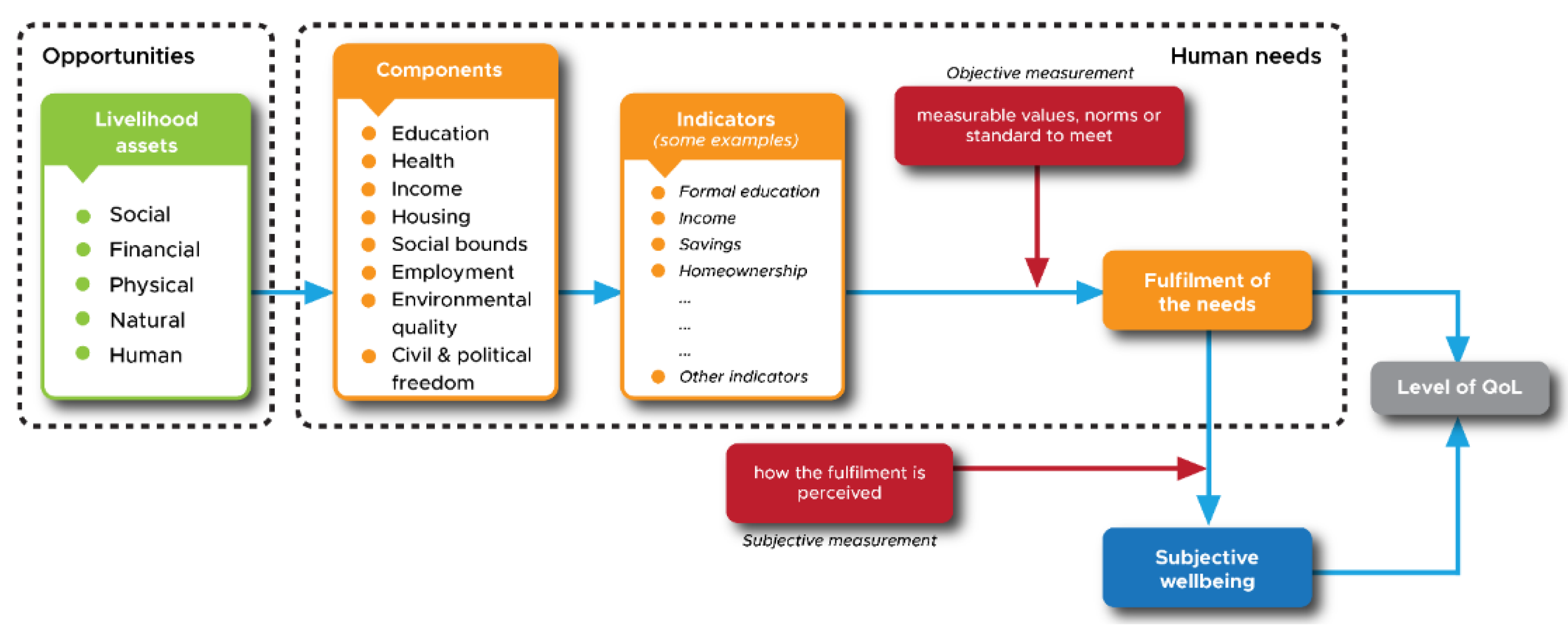

2.3. Measuring Quality of Life in Socio-Economic Development

3. Materials and Methods

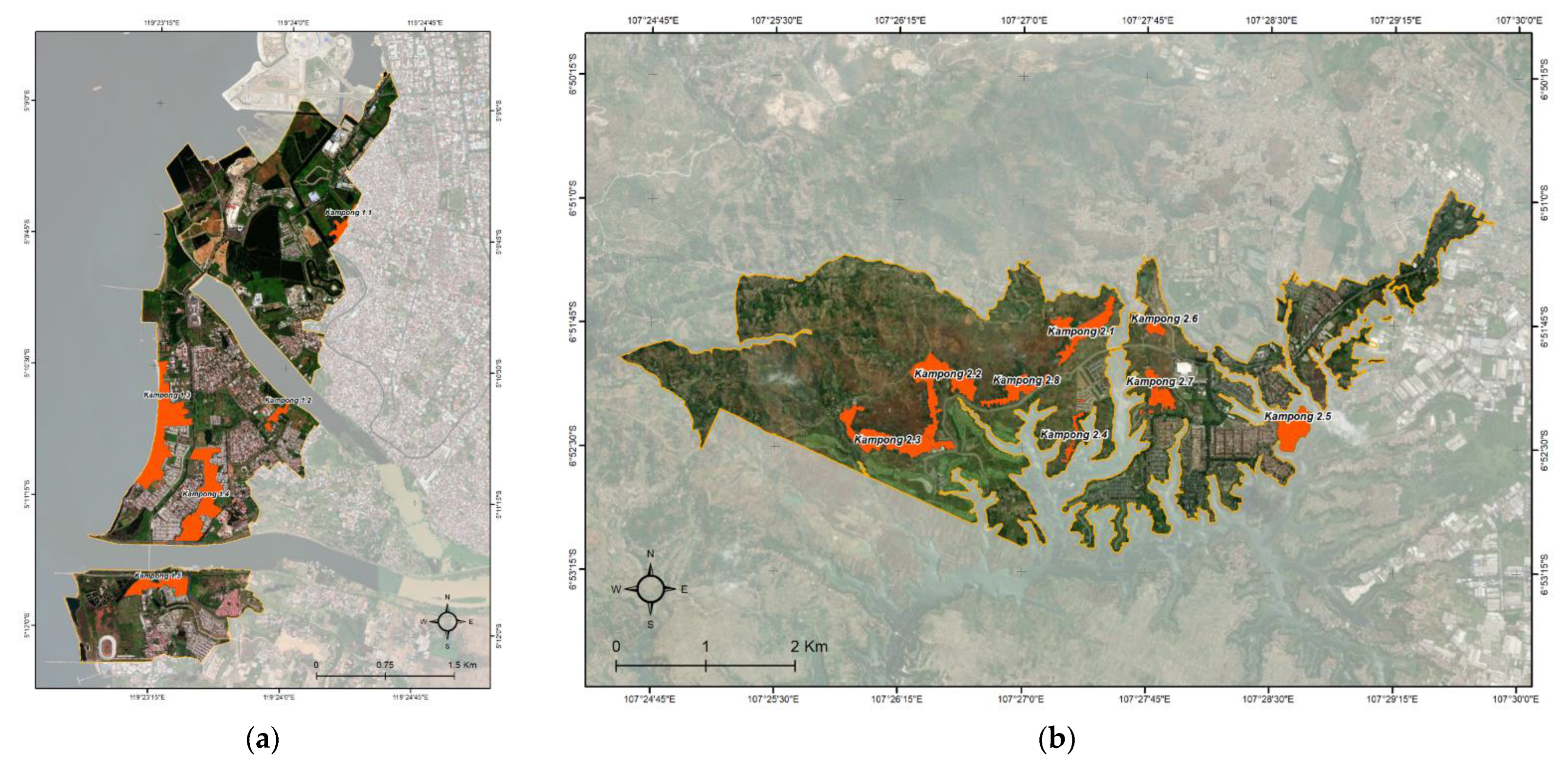

3.1. Research Location

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Evaluation of Data Survey

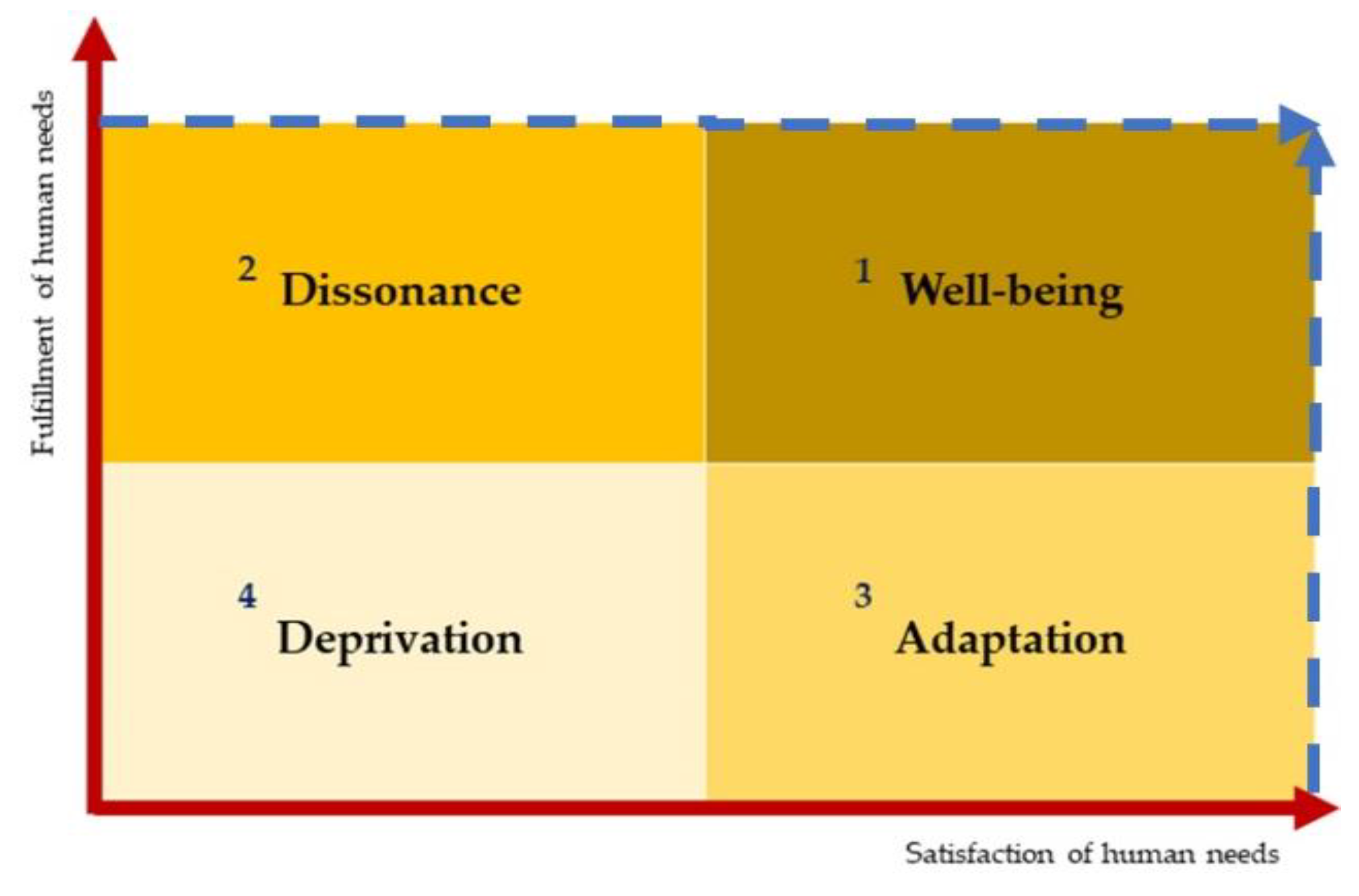

3.4. Measuring Transformation of Livelihood Assets and QoL Level

- Setting indicators of livelihood assets: natural, financial, social, human and physical assets, according to the literature review conducted.

- Scoring livelihood assets and classifying scores of the assets. The score for each indicator ranges from 1 to 6, where ≤3.0 is categorised as bad and >3.0 is categorised as good.

- Determining the indicators used to assess QoL in both an objective and a subjective manner. Eight QoL indicators were used, formed by 22 indicators. These indicators came from five livelihood assets: natural, financial, social, human and physical assets.

- Classifying the average total value of the objective and the subjective QoL. If both values were in the range of 3.1–6.0, they were considered good. Conversely, if the subjective and objective values were ≤3.0, they were considered bad.

- Determining the level of QoL. The classifications are as follows:

- If both subjective and objective scores were >3.0, QoL was classified as well-being;

- If the subjective score was ≤3.0 but the objective score was >3.0, QoL was classified as dissonance;

- If the subjective score was >3.0 but the objective score was ≤3.0, QoL was classified as adaptation;

- If both subjective and objective scores were ≤3.0, QoL is classified as deprivation.

3.5. Assessing Differences in Impacts of New Town Development on Local Communities in Different Peri-Urban Areas

4. Results

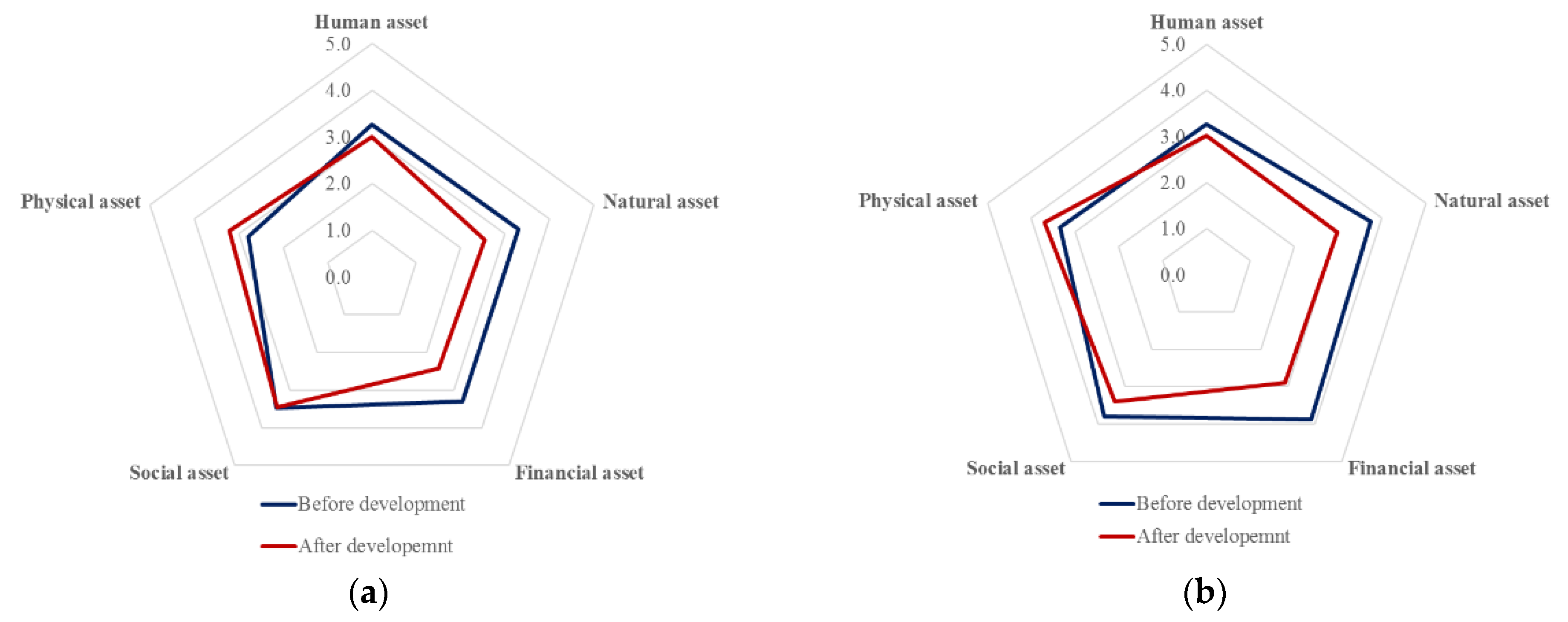

4.1. Assessing the Condition of Livelihood Assets

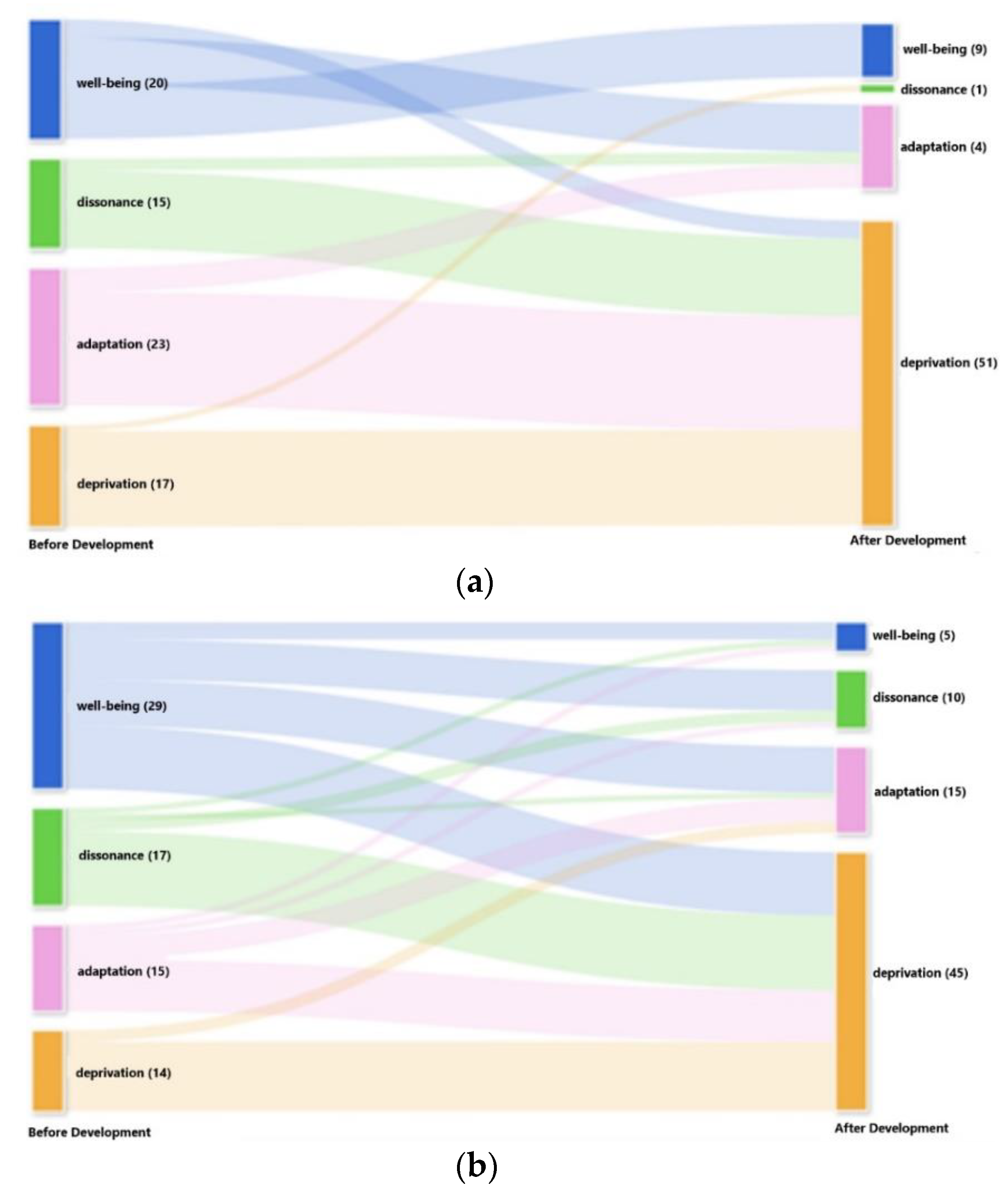

4.2. Assessing the Quality of Life of Local People

4.3. Impact of New Town Development in the Different Peri-Urban Areas on Quality-of-Life Transformation

4.3.1. Dependent Paired t-Test

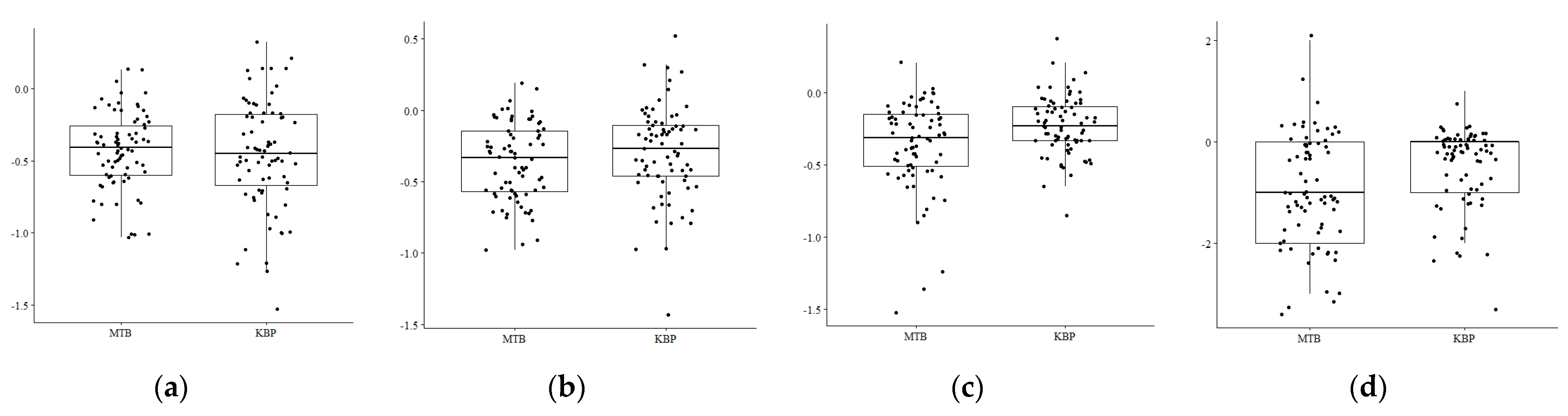

4.3.2. Independent t-Test

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, A. Environmental Planning and Management of the Peri-Urban Interface: Perspectives on an Emerging Field. Environ. Urban. 2003, 15, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D. On the Edge: Shaping the Future of Peri-Urban East Asia; Shorenstein APARC: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rauws, W.S.; De Roo, G. Exploring Transitions in the Peri-Urban Area. Plan. Theory Pract. 2011, 12, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woltjer, J. A Global Review on Peri-Urban Development and Planning. J. Perenc. Wil. Dan Kota 2014, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L.E.; Bruns, A.; Simon, D. Towards Situated Analyses of Uneven Peri-Urbanisation: An (Urban) Political Ecology Perspective. Antipode 2020, 52, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, D. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.R.; Doan, P.L. Building New Capital Cities in Africa: Lessons for New Satellite Towns in Developing Countries. Afr. Stud. 2017, 76, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D.; Muller, L. Challenges of Peri-Urbanization in the Lower Yangtze Region: The Case of the Hangzhou-Ningbo Corridor; Shorenstein APARC: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P. Too Complex to Be Managed? New Trends in Peri-Urbanisation and Its Planning in Beijing. Cities 2013, 30, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.F.B.; Batistella, M.; Moran, E.F. Socioeconomic Changes and Environmental Policies as Dimensions of Regional Land Transitions in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 74, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; Bhat, C.R. Modifiable Areal Units Problem or Perception in Modeling of Residential Location Choice? Transp. Res. Rec. 2004, 1898, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, M.B. The Formalization Fix? Land Titling, Land Concessions and the Politics of Spatial Transparency in Cambodia. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 42, 903–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, F.; Webster, C. Informality and the Development and Demolition of Urban Villages in the Chinese Peri-Urban Area. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1919–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, D. Urbanization Dynamics and Policy Frameworks in Developing East Asia; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hudalah, D.; Winarso, H.; Woltjer, J. Planning by Opportunity: An Analysis of Periurban Environmental Conflicts in Indonesia. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 2254–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octifanny, Y.; Hudalah, D. Urban Agglomeration and Extension in Northern Coast of West Java: A Transformation into Mega Region. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 79, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravitasari, A.E.; Rustiadi, E.; Mulya, S.P.; Setiawan, Y.; Fuadina, L.N.; Murtadho, A. Identifying the Driving Forces of Urban Expansion and Its Environmental Impact in Jakarta-Bandung Mega Urban Region. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 149, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, V.; Nischal, S. The Peri-Urban Interface in Shahpur Khurd and Karnera, India. Environ. Urban. 2007, 19, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomers, A.; van Noorloos, F.; Otsuki, K.; Steel, G.; van Westen, G. The Rush for Land in an Urbanizing World: From Land Grabbing Toward Developing Safe, Resilient, and Sustainable Cities and Landscapes. World Dev. 2017, 92, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, N.; Fu, B.; Lü, Y.; Zheng, Z. Changes of Livelihood Due to Land Use Shifts: A Case Study of Yanchang County in the Loess Plateau of China. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-HABITAT. Working for a Better Urban Future: Annual Progress Report 2018; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International New Town Institute. Rising in the East: Contemporary New Towns in Asia; SUN Architecture: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, I.R.; Doan, P.L. New Towns in Africa: Modernity and/or Decentralization ? New Towns as Garden Cities. In Proceedings of the 53rd African Studies Association Annual Meetings, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–21 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Golany, G. New-Town Planning: Principles and Practice; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Sujarto, D. Perencanaan Kota Baru; Penerbit ITB: Bandung, Indonesia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, S.; Henneberry, J. Understanding Urban Development Processes: Integrating the Economic and the Social in Property Research. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 2399–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Project-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: From Impoverishment Risks to an Opportunity for Development? Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoomers, A.; Otsuki, K. Addressing the Impacts of Large-Scale Land Investments: Re-Engaging with Livelihood Research. Geoforum 2017, 83, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winarso, H.; Hudalah, D.; Firman, T. Peri-Urban Transformation in the Jakarta Metropolitan Area. Habitat Int. 2015, 49, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amour, C.B.; Reitsma, F.; Baiocchi, G.; Barthel, S.; Güneralp, B.; Erb, K.H.; Haberl, H.; Creutzig, F.; Seto, K.C. Future Urban Land Expansion and Implications for Global Croplands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8939–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, S.; Hill, D.; Morgan, R. Impacts of the Delay in Construction of a Large Scale Hydropower Project on Potential Displaces. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2017, 35, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, M.; Song, Y. Vulnerability and Livelihood Restoration of Landless Households after Land Acquisition: Evidence from Peri-Urban China. Habitat Int. 2018, 79, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratomo, R.A.; Samsura, D.A.A.; Krabben, E. van der. Transformation of Local People’s Property Rights Induced by New Town Development (Case Studies in Peri-Urban Areas in Indonesia). Land 2020, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernea, M.M. The Risks and Reconstruction Model for Resettling Displaced Populations. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1569–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, B.; Webber, M. What Can We Learn from the Practice of Development-Forced Displacement and Resettlement for Organised Resettlements in Response to Climate Change? Geoforum 2015, 58, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerschmidt, D. Can Compensation Prevent Impoverishment? Reforming Resettlement through Investments and Benefit-Sharing. Hydro Nepal J. Water Energy Environ. 2009, 3, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kusiluka, M.M.; Kongela, S.; Kusiluka, M.A.; Karimuribo, E.D.; Kusiluka, L.J.M. The Negative Impact of Land Acquisition on Indigenous Communities’ Livelihood and Environment in Tanzania. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, J.M. Theoretical Perspectives Guiding QOL Indicator Projects. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 103, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkoglu, H. Sustainable Development and Quality of Urban Life. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 202, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouw, N.; Gupta, J. Inclusive Development: A Multi-Disciplinary Approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 24, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheyvens, R.; Biddulph, R. Inclusive Tourism Development. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Kundu, R.; Chen, X. Building for What and Whom? New Town Development as Planned Suburbanization in China and India. Res. Urban Sociol. 2010, 10, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M.; Franco, J.C. Global Land Grabbing and Political Reactions “From Below”. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 1723–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Fisher, B.; Ali, S.; Beer, C.; Bond, L.; Boumans, R.; Danigelis, N.L.; Dickinson, J.; Elliott, C.; Farley, J.; et al. Quality of Life: An Approach Integrating Opportunities, Human Needs, and Subjective Well-Being. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 61, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M.K.; Winarso, H. Transformasi Sosial Ekonomi Masyarakat Peri-Urban Di Sekitar Pengembangan Lahan Skala Besar: Kasus Bumi Serpong Damai. J. Reg. City Plan. 2007, 18, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cirolia, L.R. (W)Escaping the Challenges of the City: A Critique of Cape Town’s Proposed Satellite Town. Urban Forum 2014, 25, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T.G. The Spatiality of Urbanization: The Policy Challenges of Mega-Urban and Desakota Regions of Southeast Asia. UNU-IAS Work. Pap. 2009, 161, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Adell, G. Theories and Models of the Peri-Urban Interface: Changing Conceptual Landscape; Draf for Discussion; UCL Discovery: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rakodi, C.; Lloyd-Jones, T. Urban Livelihoods: A People-Centred Approach to Reducing Poverty; Earthscan Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tacoli, C. Rural-Urban Interactions: A Guide to the Literature. Environ. Urban. 1998, 10, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiba, B.; Huchzermeyer, M. Contentious Development: Peri-Urban Studies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2002, 2, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, V. Growing City, Shrinking Hinterland: Land Acquisition, Transition and Conflict in Peri-Urban Gurgaon, India. Environ. Urban. 2009, 21, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.; Purushothaman, S.; Hunshal, C. Changing Frontiers: The Peri-Urban Interface Hubli–Dharwad, India; Brook, R., Purushothaman, S., Hunshal, C., Eds.; Books for Change: Bangalore, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Caldelas, R.; Pena-Salmon, C.; Ranfla-González, A.; Venegas-Cardoso, R.; Leyva-Camacho, O.; Ley-Garcia, J. Approaches to Analysing the Rural-Urban Interface: Comprehensive Development Views from Town and Countryside. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2010, 129, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T.G.; Robinson, I.M. The Mega-Urban Regions of Southeast Asia; University of British Columbia Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Coy, M.; Sandholz, S.; Töpfer, T.; Zirkl, F. Metropolitan Regions: Challenges for Sustainability and Governance of Periurban Areas in Brazil. Confins 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, M. A Regional Network Strategy for Reciprocal Rural-Urban Linkages. Third World Plan. Rev. 1998, 20, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, T. The Urbanisation of Java, 2000–2010: Towards ‘the Island of Mega-Urban Regions. ’ Asian Popul. Stud. 2017, 13, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.A. Extending Urban Services in Developing Countries: Policy Options and Organisational Choices. Public Adm. Dev. 1986, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.C. China on the Move: Migration, the State, and the Household; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinis, G.; Koutsias, N.; Arianoutsou, M. Monitoring Land Use/Land Cover Transformations from 1945 to 2007 in Two Peri-Urban Mountainous Areas of Athens Metropolitan Area, Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 490, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conedera, M.; Del Biaggio, A.; Seeland, K.; Moretti, M.; Home, R. Residents’ Preferences and Use of Urban and Peri-Urban Green Spaces in a Swiss Mountainous Region of the Southern. Alps. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, A. The “Sowing of Concrete”: Peri-Urban Smallholder Perceptions of Rural-Urban Land Change in the Central Peruvian Andes. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.; Tsurusaki, N.; Divigalpitiya, P. Land Use/Land Cover Change Detection and Urban Sprawl in the Peri-Urban Area of Greater Cairo since the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. J. Land Use Sci. 2020, 15, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.; Supriatna. Kerentanan Lingkungan Pantai Kota Pesisir Di Indonesia. J. Ilmu Dan Teknol. Kelaut. Trop. 2011, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Agricultural Land (% of Land Area)-Indonesia. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/AG.LND.AGRI.ZS?locations=ID (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Pribadi, D.O.; Vollmer, D.; Pauleit, S. Impact of Peri-Urban Agriculture on Runoff and Soil Erosion in the Rapidly Developing Metropolitan Area of Jakarta, Indonesia. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 2129–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, V.P. Conscious Coastal Cities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratomo, R.A.; Ayuni, S.I.; Fitrianingsih, D. Implikasi Pembangunan Kota Baru Terhadap Perubahan Fisik Kawasan Dan Sosial-Ekonomi Masyarakat Lokal: Studi Kasus Pembangunan Kota Harapan Indah, Bekasi. J. Pengemb. Kota 2021, 9, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandere, N.; Ness, B.; Anderberg, S. Peri-Urban Development, Livelihood Change and Household Income: A Case Study of Peri-Urban Nyahururu, Kenya. J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev. 2010, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pratomo, R.A.; Samsura, D.A.A.; Krabben, E. Towards Sustainable Life of Local Communities in Coastal Cities: A Longitudinal Study of New Town Development in Makassar. In Routledge Handbook of Urban Indonesia; Rukmana, D., Roitman, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel, P.; Quansah, C.; Penning De Vries, F. Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture in West Africa: Characteristics, Challenges, and Need for Action. In Urban Agriculture in West Africa: Contributing to Food Security and Urban Sanitation = Agriculture Urbaine en Afrique de L’Ouest: Une Contribution à la Sécurité Alimentaire et à L’assainissement des Villes; Smith, O.B., Ed.; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999; p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, B.R.; Pollnac, R.B. Among Coastal and Non-Coastal Communities Resources Management Project-Indonesia. J. Pesisir Dan Lautan 1999, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hudalah, D.; Winarso, H.; Woltjer, J. Peri-Urbanisation in East Asia: A New Challenge for Planning? Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2007, 29, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legates, R.; Hudalah, D. Peri-Urban Planning for Developing East Asia: Learning from Chengdu, China and Yogyakarta/Kartamantul, Indonesia. J. Urban Aff. 2014, 36 (Suppl. S1), 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, D.B. Urban Planning in China: Continuity and Change. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2006, 72, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Urban Environments: Issues on the Peri-Urban Fringe. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2008, 33, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R. Sustainable New Towns. Stockholm’s Rail-Served Satellites. Cities 1995, 12, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.C.Y. The Influence of Suburbanization on the Access to Employment of Workers in the New Towns: A Case Study of Tin Shui Wai, Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y. Restoration of Forests Associated with New Town Development in Hong Kong. In A Goal-Oriented Approach to Forest Landscape Restoration; Stanturf, J., Madsen, P., Lamb, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.K.W. Issues in Urban Redevelopment: The Land Development Corporation. Built Environ. 1985, 11, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Kundu, R. Localizing the Production of Global Cities: A Comparison of New Town Developments Around Shanghai and Kolkata. City Community 2009, 8, 433–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, N.H.; Viqar, S. Producing Cosmopolitan Karachi: Freedom, Security and Urban Redevelopment in the Post-Colonial Metropolis. South Asian Hist. Cult. 2014, 5, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, A.B. Slowing Metropolitan City Growth in Asia: Policies, Programs, and Results. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1979, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedele, J.A.; Shimboyo, S.; Sitoka, S.; Gaoseb, F. Assessment of Natural Radioactivity in the Soils of Rossing Uranium Mine and Its Satellite Town in Western Namibia, Southern Africa. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2010, 619, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Chatterjee, S. Satellite Town Development in India in Retrospect and Prospect: A Case of Navi Mumbai. Spandre 2015, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, M.J. The Effects of Seoul’s New-Town Development on Suburbanization and Mobility: A Counterfactual Approach. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 2171–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbach, A. Do New Towns Increase Disaster Risk? Evidence from Kolkata, India. Habitat Int. 2014, 43, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Q.; Chan, E.H.W.; Yeung, S.C.W.; Han, J.B. Urban Fringe Land Use Transitions in Hong Kong: From New Towns to New Development Areas. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insa, R.; Ciriza. Two Ways of New Towns Development: A Tale of Two Cities. In Urban Development; Polyzos, S., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.J.; Torres, S.B. Company Towns; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Shin, H.R. Negotiating the Polycentric City-Region: Developmental State Politics of New Town Development in the Seoul Capital Region. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 1333–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujarto, D. Perkembangan Kota Baru. J. PWK 1993, 4, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, D.E.; Craig, P.H.; Malaney, P.N. The Quality of Life in Rural Asia; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Omar, D. Urban Planning and the Quality of Life in Putrajaya, Malaysia. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2006, 86, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, J.O.; Godfrey, B.J. Frontier Urbanization in the Brazilian Amazon: A Theoretical Framework for Urban Transition. Yearb.-Conf. Lat. Am. Geogr. 1990, 16, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B.; Bregón, N. Multicentro: A New Town in-Town for Old Bogotá. Third World Plan. Rev. 1979, 1, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ma, Z.; Song, W. Scaling-up Strategy as an Appropriate Approach for Sustainable New Town Development? Lessons from Wujin, Changzhou, China. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5682–5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasrodashti, R.E.; Majedi, H.; Paydar, M. Assessment of Residential Satisfaction in Mehr Housing Scheme: A Case Study of Sadra New Town, Iran. Hous. Theory Soc. 2017, 34, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneralp, B.; Reba, M.; Hales, B.U.; Wentz, E.A.; Seto, K.C. Trends in Urban Land Expansion, Density, and Land Transitions from 1970 to 2010: A Global Synthesis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.R. A Model of Indonesian City Structure. Geogr. Rev. 1993, 83, 374–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartiwa, A. Karakteristik Jaringan Perusahaan Properti Di Jabodetabek; Institut Teknologi Bandung: Kota Bandung, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Firman, T. New Town Development in Jakarta Metropolitan Region: A Perspective of Spatial Segregation. Habitat Int. 2004, 28, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diningrat, R. Segregasi Spasial Perumahan Skala Besar: Studi Kasus Kota Baru Kota Harapan Indah (KHI) Bekasi. J. Perenc. Wil. Dan Kota 2015, 26, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Apriyanto, H.; Eriyanto; Rustiadi, E.; Mawardi, I. Status Berkelanjutan Kota Tangerang Selatan-Banten Dengan Menggunakan Key Performance Indicators. J. Mns. Dan Lingkung. 2015, 22, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sukarsa, R.; Rudiarto, I. Pengaruh Pembangunan Bukit Semarang Baru Terhadap Sosial-Ekonomi Fisik Lingkungan Masyarakat Sekitarnya. Tek. PWK Perenc. Wil. Kota 2014, 3, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, L.T. How Low-Income Residents Can Benefit from Urban Development: The LA Live Community Benefits Agreement. City Community 2012, 11, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huu, T.P. Dilemmas of Hydropower Development in Vietnam: Between Dam-Induced Displacement and Sustainable Development; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Craglia, M.; Leontidou, L.; Nuvolati, G.; Schweikart, J. Towards the Development of Quality of Life Indicators in the “digital” City. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2004, 31, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shameem, M.I.M.; Momtaz, S.; Rauscher, R. Vulnerability of Rural Livelihoods to Multiple Stressors: A Case Study from the Southwest Coastal Region of Bangladesh. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 102, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, R. The Quality of Life and the Environment. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 35, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kõrreveski, K. Measuring Well-Being and Quality of Life Using OECD Indicators. Q. Bull. Stat. Est. 2011, 4, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Graham, J.; Ditto, P.H.; Haidt, J. Understanding Libertarian Morality: The Psychological Roots of an Individualist Ideology. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.B. Rural Livelihood Change? Household Capital, Community Resources and Livelihood Transition. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.R.; Thompson, J.P.; Saegert, S. The Role of Social Capital in Combating Poverty. In Social Capital and Poor Communities; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Anielski, M. The Economics of Happiness: Building Genuine Wealth; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2007; Volume 59. [Google Scholar]

- Mella, P.; Gazzola, P. The Holonic View of Organizations and Firms. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2017, 34, 354–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, C. Does Development Make You Happy? Subjective Wellbeing and Economic Growth in Developing Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 73, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S. Conceptualizing and Measuring Quality of Life for National Policy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 58, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfazghi, E.S.; Martinez, J.A.; Verplanke, J.J. Variability of Quality of Life at Small Scales: Addis Ababa, Kirkos Sub-City. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 98, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, M.; Canova, L. An Assessment of the Quality of Life in the European Union Based on the Social Indicators Approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 87, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.B.; Bourguignon, F. Introduction: Income Distribution and Economics. Handb. Income Distrib. 2000, 1, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeten, P.; Burki, S.J. Basic Needs: Some Issues. World Dev. 1978, 6, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, R.C.; Togawa, T.; Ooba, M.; Gomi, K.; Nakamura, S.; Hijioka, Y.; Kameyama, Y. A Review of Quality of Life (QOL) Assessments and Indicators: Towards a “QOL-Climate” Assessment Framework. Ambio 2019, 48, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhe, R.T.; Martinez, J.; Verplanke, J. Adaptation and Dissonance in Quality of Life: A Case Study in Mekelle, Ethiopia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 118, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. Urban Quality of Life: A Case Study of Guwahati. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 88, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenhuizing, J.; de Kraker, J.; Valkering, P. Design of a Quality-of-Life Monitor to Promote Learning in a Multiactor Network for Sustainable Urban Development. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.D.; Martins, I.; Brito, P. Measuring Subjective Quality of Life: A Survey to Porto’s Residents. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2007, 2, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J. Subjective Quality of Life Measurement in Taipei. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, G.; Schober, B. The Satisfied Poor: Development of an Intervention-Oriented Theoretical Framework to Explain Satisfaction with a Life in Poverty. Soc. Indic. Res. 1993, 28, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, J.M.; Michalos, A.C.; Ferriss, A.L.; Easterlin, R.A.; Patrick, D.; Pavot, W. The Quality-of-Life (QOL) Research Movement: Past, Present, and Future. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006, 76, 343–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, M.B.; Fredell, K.A.; Frideres, J.S. Basic Minimum Needs, Quality of Life and Selected Correlates: Explorations in Villages in Northern India. Soc. Indic. Res. 1997, 42, 245–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for International Development. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; DFID: London, UK, 1999.

- Zapf, W. Individuelle Wohlfahrt: Lebensbedingungen Und Wahrgenom-Mene Lebensqualität. In Lebensqualität in der Bundesrepublik: Objektive Lebensbedingungen und subjektives Wohlbefinden; Glatzer, W., Zapf, W., Berger, R., Eds.; Frankfurt: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, T.S. Subjective Assessment of Urban Quality of Life in Singapore (1997–1998). Habitat Int. 2000, 24, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, H.H. Subjective Social Indicators: Benefits and Limitations for Policy Making-An Introduction to This Special Issue. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megawati, D.R.; Ju, S.R.; Hanan, H. The Trend of Housing Design and Town Planning of New Towns in Indonesia. J. Korean Hous. Assoc. 2014, 25, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Surya, B. Perubahan Fisik Spasial Kawasan Pinggiran Memarginalkan Komunitas Lokal. J. Tata Loka 2011, 13, 212–223. [Google Scholar]

- Surya, B.; Ahmad, D.N.A.; Sakti, H.H.; Sahban, H. Land Use Change, Spatial Interaction, and Sustainable Development in the Metropolitan Urban Areas, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. Land 2020, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunas, D.; Peresthu, A. The Self-Help Housing in Indonesia: The Only Option for the Poor? Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.P. Nonprobability Sampling; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, A.S.; Prakash, A.; Saxena, P.; Nigam, A. Sampling: Why and How of It? Indian J. Med. Spec. 2013, 4, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, G. Practical Sampling; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barratt, M.J.; Lenton, S. Representativeness of Online Purposive Sampling with Australian Cannabis Cultivators. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, S.; Leeper, T.J. Identities and Intersectionality: A Case for Purposive Sampling in Survey-Experimental Research. In Experimental Methods in Survey Research: Techniques that Combine Random Sampling with Random Assignment; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.D. When Attaining the Best Sample Is out of Reach: Nonprobability Alternatives When Engaging in Public Administration Research. J. Public Aff. Educ. 2019, 25, 314–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmad, R.; Rimba, F.; Wirda, M.A. Study of Population Activities in Establishing the Economic Welfare of Belawan Coastal Communities, North Sumatra. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 7, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.R.; Schindler, P.S. Bussines Research Method, 9th ed.; McGraw-Hill International Editions; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education, Inc.: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ghozali, I. Structural Equation Modelling, 2nd ed.; Universitas Diponegoro: Semarang, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the Beginning: An Introduction to Coefficient Alpha and Internal Consistency. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.B.; Lissitz, R.W.; Mulaik, S.A. Limitations of Coefficient Alpha as an Index of Test Unidimensionality1. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 37, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E. Summated Rating Scale Construction. An Introduction; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Vaske, J.J. Survey Research and Analysis: Applications in Parks, Recreation and Human Dimensions; Venture Publishing: State College, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Oktaviani, M.A.; Notobroto, H.B. Perbandingan Tingkat Konsistensi Normalitas Distribusi Metode Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors, Shapiro-Wilk, Dan Skewness-Kurtosis. J. Biom. Dan Kependud. 2014, 3, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Mordkoff, T.J. The Assumption(s) of Normality. Available online: http://www2.psychology.uiowa.edu/faculty/mordkoff/GradStats/part 1/I.07 normal.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality Test for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovesana, A.; Senior, G. How Small Is Big: Sample Size and Skewness. Assessment 2018, 25, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.K. T Test as a Parametric Statistic. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2015, 68, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.K.; Park, J.H. More about the Basic Assumptions of T-Test: Normality and Sample Size. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. Complexity and Self-Organization; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller, W.; Lavorel, S.; Araújo, M.B.; Sykes, M.T.; Prentice, I.C. Climate Change Threats to Plant Diversity in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8245–8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Fisher, B.; Ali, S.; Beer, C.; Bond, L.; Boumans, R.; Danigelis, N.L.; Dickinson, J.; Elliott, C.; Farley, J.; et al. An Integrative Approach to Quality of Life Measurement, Research, and Policy. Surv. Perspect. Integr. Environ. Soc. 2008, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hollander, A.E.M.; Staatsen, B.A.M. Health, Environment and Quality of Life: An Epidemiological Perspective on Urban Development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Mittelhammer, R.C.; Wandschneider, P.R. Measuring Quality of Life across Countries: A Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes Approach. J. Socio-Econ. 2011, 40, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriyie, K.; Abass, K.; Adomako, J.A.A. Urbanisation of the Rural Landscape: Assessing the Effects in Peri-Urban Kumasi. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2014, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haregeweyn, N.; Tesfaye, S.; Tsunekawa, A.; Tsubo, M.; Meshesha, D.T.; Adgo, E.; Elias, A. Dynamics of Land Use and Land Cover and Its Effects on Hydrologic Responses: Case Study of the Gilgel Tekeze Catchment in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, T.; Hasan, M.; Haque, A.; Jayasinghe, S.; Kumar, L. Sustainability of Coastal Agriculture under Climate Change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayanti, W.P.; Pratomo, R.A. Adaptation of Social-Economic Livelihoods in Coastal Community: The Case of Mangunharjo Sub-District, Semarang City. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 227, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.L.; Murray, G.; Flaherty, M. Strengthening Threatened Communities through Adaptation: Insights from Coastal Mozambique. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, art6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, V.; McKenna, J. The Potential Role of Sustainability Science in Coastal Zone Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxbury, J.; Dickinson, S. Principles for Sustainable Governance of the Coastal Zone: In the Context of Coastal Disasters. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mee, L. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea: The Coastal Zone in an Era of Globalisation. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2012, 96, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Education: formal education, access to informal education, educational insurance, access to educational facilities | Civil and political freedom: involvement in organisations, active in decision-making |

| Health: personal disease, health insurance, access to health facilities | Social bonds: trust, tolerance, cooperation, access to information |

| Income: adequate income, savings, access to credit, landownership | Employment: type of jobs, knowledge and skills, access to work location |

| Housing: homeownership, housing condition, comfort, access to the house | Environmental quality: access to fresh air, access to clean water |

| Metro Tanjung Bunga | Kota Baru Parahyangan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kampung | Location | Number of Respondents | Kampung | Location | Number of Respondents |

| Kampung 1.1 | RW 1 Kelurahan Bontorannu & RW 4, 6, 7 Kelurahan Maccini Sombala | 15 | Kampung 2.1 | RW 2 Desa Bojonghaleuang | 9 |

| Kampung 1.2 | RW 1, 2, and 7 Kelurahan Tanjung Merdeka | 16 | Kampung 2.2 | RW 7 Desa Bojonghaleuang | 10 |

| Kampung 1.3 | RW 5 and 6 Kelurahan Tanjung Merdeka | 16 | Kampung 2.3 | RW 3 and 4 Desa Cikande | 9 |

| Kampung 1.4 | RW 4 Kelurahan Tanjung Merdeka | 14 | Kampung 2.4 | RW 3 and 4 Desa Bojonghaleuang | 9 |

| Kampung 1.5 | RW 10 Kelurahan Barombong | 14 | Kampung 2.5 | RW 10 Desa Cipeundeuy | 9 |

| Total | 75 | Kampung 2.6 | RW 19 Desa Kertajaya | 10 | |

| Kampung 2.7 | RW 20 Desa Kertajaya | 9 | |||

| Kampung 2.8 | RW 5 and 6 Desa Bojonghaleuang | 10 | |||

| Total | 75 | ||||

| No. | QoL Indicators | Factor Loading | No. | QoL Indicators | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Education (α = 0.772, 0.721) | 5 | Social bonds (α = 0.711, 0.729) | ||

| 0.692 |

| 0.807 | ||

| 0.668 |

| 0.748 | ||

| 0.641 |

| 0.709 | ||

| 0.634 | 6 | Employment (α = 0.732, 0.729) | ||

| 2 | Health (α = 0.762, 0.721) |

| 0.801 | ||

| 0.742 |

| 0.732 | ||

| 0.738 |

| 0.705 | ||

| 0.713 | 7 | Environmental quality (α = 0.764, 0.726) | ||

| 3 | Income (α = 0.921, 0.834) |

| 0.767 | ||

| 0.931 |

| 0.741 | ||

| 0.771 | 8 | Civil and political freedom (α = 0.771, 0.763) | ||

| 4 | Housing (α = 0.962, 0.819) |

| 0.793 | ||

| 0.907 |

| 0.711 | ||

| 0.811 | ||||

| 0.782 | ||||

| Variables | Before Development | After Development | p-Value | Result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||||

| Livelihood assets | |||||||

| MTB | 2.88 | ±0.49 | 2.45 | ±0.38 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| KBP | 3.06 | ±0.58 | 2.61 | ±0.62 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| Objective QoL | |||||||

| MTB | 2.83 | ±0.44 | 2.46 | ±0.36 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| KBP | 3.07 | ±0.51 | 2.78 | ±0.57 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| Subjective QoL | |||||||

| MTB | 3.08 | ±0.41 | 2.72 | ±0.38 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| KBP | 3.21 | ±0.56 | 2.98 | ±0.53 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| Overall QoL | |||||||

| MTB | 2.51 | ±1.11 | 1.60 | ±1.01 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| KBP | 2.53 | ±1.15 | 2.11 | ±1.14 | <0.001 * | Significant | |

| Variables | Transformation | p-Value | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. Deviation | ||||

| Livelihood asset | |||||

| MTB | −0.43 | ±0.26 | 0.6316 | Not significant | |

| KBP | −0.46 | ±0.38 | |||

| Objective QoL | |||||

| MTB | −0.36 | ±0.27 | 0.158 | Not significant | |

| KBP | −0.29 | ±0.33 | |||

| Subjective QoL | |||||

| MTB | −0.36 | ±0.31 | 0.002 * | Significant | |

| KBP | −0.23 | ±0.20 | |||

| Overall QoL | |||||

| MTB | −0.91 | ±1.04 | 0.001 * | Significant | |

| KBP | −0.43 | ±0.74 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pratomo, R.A.; Samsura, D.A.A.; van der Krabben, E. Living on the Edge: Comparing the Quality of Life Transformation of Local Communities Induced by New Town Development in Different Peri-Urban Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013435

Pratomo RA, Samsura DAA, van der Krabben E. Living on the Edge: Comparing the Quality of Life Transformation of Local Communities Induced by New Town Development in Different Peri-Urban Areas. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013435

Chicago/Turabian StylePratomo, Rahmat Aris, D. Ary A. Samsura, and Erwin van der Krabben. 2022. "Living on the Edge: Comparing the Quality of Life Transformation of Local Communities Induced by New Town Development in Different Peri-Urban Areas" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013435

APA StylePratomo, R. A., Samsura, D. A. A., & van der Krabben, E. (2022). Living on the Edge: Comparing the Quality of Life Transformation of Local Communities Induced by New Town Development in Different Peri-Urban Areas. Sustainability, 14(20), 13435. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013435