Assessing the Relationship between English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Their Acceptance of Online Teaching in the Chinese Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

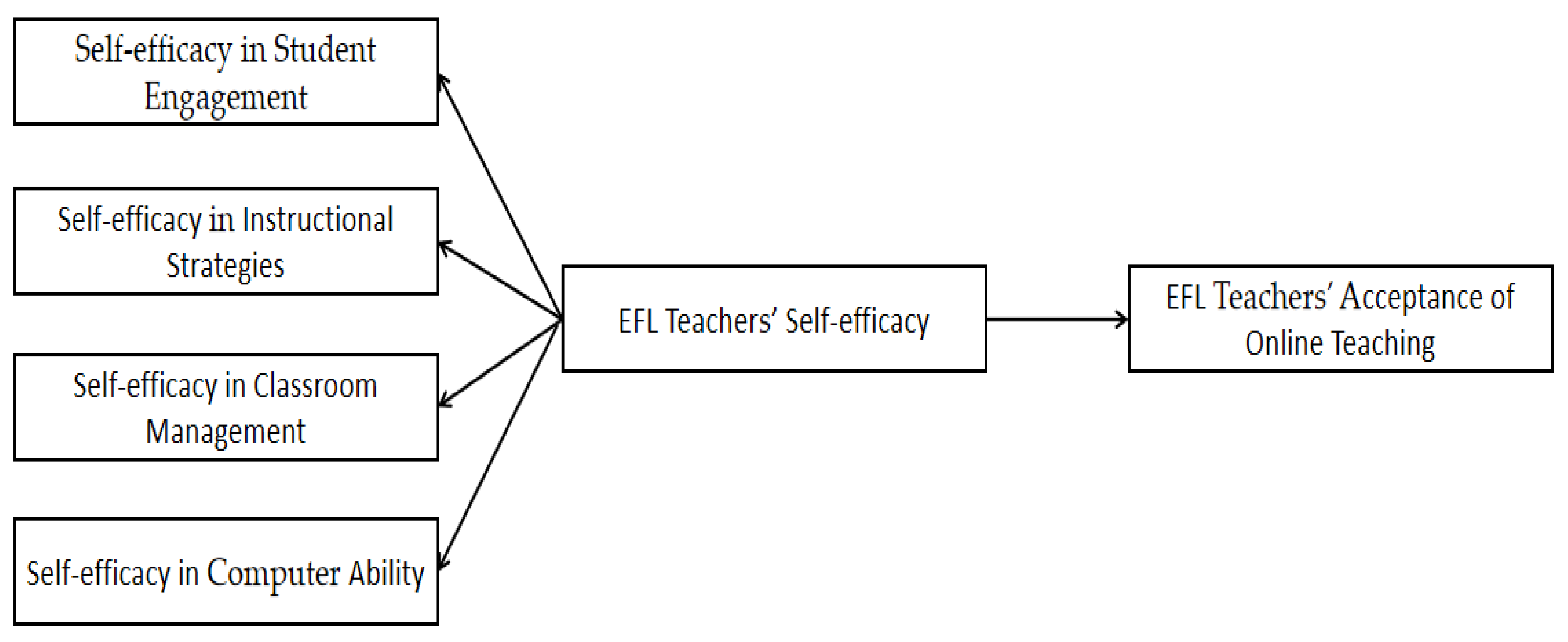

- Q1: To what extent do EFL teachers experience online self-efficacy?

- Q2: To what extent do they accept online teaching?

- Q3: Is EFL teachers’ self-efficacy associated with their acceptance of online teaching?

- Q4: Which is the best predictor of EFL teachers’ acceptance of online teaching in relation to the specific aspects of self-efficacy: students’ engagement, instructional strategies, classroom management, or computer skills?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Efficacy and Teacher Self-Efficacy

2.2. Teacher Self-Efficacy and Technology Acceptance

2.3. Online Teaching Self-Efficacy

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

3.2. Participants

3.3. Questionnaire

3.3.1. The Scale of Behavioral Intention in Online Teaching

3.3.2. The Scale of Online Teachers’ Self-Efficacy

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of Teachers’ Acceptance of Online Teaching (Q1)

4.2. Descriptive Statistical Analysis of EFL Teachers’ Self-Efficacy (Q2)

4.3. The Relationship between EFL Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and the Acceptance of Online Teaching (Q3)

4.4. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis (Q4)

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chakma, U.; Li, B.; Kabuhung, G. Creating online metacognitive spaces: Graduate research writing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Issues Educ. Res. 2021, 31, 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gacs, A.; Goertler, S.; Spasova, S. Planned online language education versus crisis-prompted online language teaching: Lessons for the future. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2020, 53, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B. Ready for online? Exploring EFL teachers’ ICT acceptance and ICT literacy during COVID-19 in mainland China. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2022, 60, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Gao, C.; Yang, J. Chinese University EFL Teachers’ Perceived Support, Innovation, and Teaching Satisfaction in Online Teaching Environments: The Mediation of Teaching Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 761106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samiri, R.A. English Language Teaching in Saudi Arabia in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Challenges and Positive Outcomes. Arab World Engl. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steering Committee for Foreign Language Teaching in Higher Institutions. College English Teaching Guide (2017); Ministry of Education: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Wong, S.L.; Khambari, M.N.M.; Noordin, N. Understanding English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Teachers’ Acceptance to Teach Online During Covid-19: A Chinese Case. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Huang, F.; Hoi, C.K.W. Explicating the influences that explain intention to use technology among English teachers in China. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2018, 26, 460–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.B.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10919/104648 (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Tao, J.; Gao, X.A. Teaching and learning languages online: Challenges and responses. System 2022, 107, 102819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X. Emergency remote teaching of English as a foreign language during COVID-19: Perspectives from a university in China. IJERI Intern. J. Educ. Res. Innov. 2021, 15, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ogawa, C. Online teaching self-efficacy—How English teachers feel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indones. Tesol J 2021, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Wyatt, M. Exploring the self-efficacy beliefs of Vietnamese pre-service teachers of English as a foreign language. System 2021, 96, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chu, W.; Wang, Y. Unpacking EFL teacher self-efficacy in livestream teaching in the Chinese context. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 717129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y.J.; Park, S.; Lim, E. Factors influencing preservice teachers’ intention to use technology: TPACK, teacher self-efficacy, and technology acceptance model. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2018, 21, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lauermann, F.; Berger, J.-L. Linking teacher self-efficacy and responsibility with teachers’ self-reported and student-reported motivating styles and student engagement. Learn. Instr. 2021, 76, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Zhang, L.J.; Dixon, H.R. Teacher engagement in language teaching: Investigating self-Efficacy for teaching based on the project “Sino-Greece online Chinese language classrooms”. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 710736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Wang, J.; Chai, C.-S. Understanding Hong Kong primary school English teachers’ continuance intention to teach with ICT. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn 2021, 34, 528–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, T.; Kukkonen, J.; Kontkanen, S.; Sormunen, K.; Dillon, P.; Sointu, E. The impact of authentic learning experiences with ICT on pre-service teachers’ intentions to use ICT for teaching and learning. Comput. Educ. 2015, 81, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipjutorus, W.; Hansen, S.; Brown, M. Investigating a relationship between learner control and self-efficacy in an online learning environment. J. Open Flex. Distance Learn. 2012, 16, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, C.; Flores, M.A. COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S.; Kostoulas, A. 1. Introduction to Language Teacher Psychology. In Language Teacher Psychology; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Talsma, K.; Schüz, B.; Schwarzer, R.; Norris, K. I believe; therefore I achieve (and vice versa): A meta-analytic cross-lagged panel analysis of self-efficacy and academic performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 61, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, E. Self-efficacy in online learning environments: A literature review. Contemp. Issues Educ. Res. (CIER) 2016, 9, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2001, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M.; Koomen, H.M. Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatlevik, I.K.; Hatlevik, O.E. Examining the relationship between teachers’ ICT self-efficacy for educational purposes, collegial collaboration, lack of facilitation and the use of ICT in teaching practice. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, R.; Tavassoli, K. Teacher efficacy, burnout, teaching style, and emotional intelligence: Possible relationships and differences. Iran. J. Appl. Linguist. 2011, 14, 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón, C.T. Teachers’ perceived efficacy among English as a foreign language teacher in middle schools in Venezuela. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2005, 21, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-C. Conceptions of learning in technology-enhanced learning environments: A review of case studies in Taiwan. Asian Assoc. Open Univ. J. 2017, 12, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J.; Jäger-Biela, D.J.; Glutsch, N. Adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closure: Teacher education and teacher competence effects among early career teachers in Germany. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2020, 43, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, S.; Shaya, N. Exploring predictors of teachers’ self-efficacy for online teaching in the Arab world amid COVID-19. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 8093–8110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toto, G.A.; Limone, P. Effectiveness and Application of Assisted Technology in Italian Special Psycho-Education: A Pilot Study. J. e-Learn. High. Educ. 2020, 2020, 177729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T. Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 2021, 50, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A. Toward a framework for strengthening participants’ self-efficacy in online education. Asian Assoc. Open Univ. J. 2020, 15, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online education and its effective practice: A research review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. 2016, 15, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corry, M.; Stella, J. Teacher self-efficacy in online education: A review of the literature. Res. Learn. Technol. 2018, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.-C.; Walker, A.E.; Schroder, K.E.; Belland, B.R. Interaction, Internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. Internet High. Educ. 2014, 20, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatlevik, O.E. Examining the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy, their digital competence, strategies to evaluate information, and use of ICT at school. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 61, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Tondeur, J.; Siddiq, F.; Baran, E. The importance of attitudes toward technology for pre-service teachers’ technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge: Comparing structural equation modeling approaches. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinia, K.A.; Anderson, M.L. Online teaching efficacy of nurse faculty. J. Prof. Nurs. 2010, 26, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissau, S.; Adams, M.J.; Algozzine, B. Middle school foreign language instruction: A missed opportunity? Foreign Lang. Ann. 2015, 48, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, S.; Idleman, L. Online teaching efficacy: A product of professional development and ongoing support. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2017, 14, 20160033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W. COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: A case study of Peking University. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, S. Instructional strategies for online teaching in COVID-19 pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpershoek, H.; Harms, T.; de Boer, H.; van Kuijk, M.; Doolaard, S. A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 643–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulou, M.S.; Reddy, L.A.; Dudek, C.M. Relation of teacher self-efficacy and classroom practices: A preliminary investigation. School Psychol. Int. 2019, 40, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Chutiyami, M.; Zhang, Y.; Nicoll, S. Online teaching self-efficacy during COVID-19: Changes, its associated factors and moderators. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6675–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvitz, B.S.; Beach, A.L.; Anderson, M.L.; Xia, J. Examination of faculty self-efficacy related to online teaching. Innov. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolighan, T.; Owen, M. Teacher efficacy for online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brock Educ. J. 2021, 30, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Hair, J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Black, W.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning EMEA: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS; Open University Press/McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Lee, J. Investigating the relationship of target language proficiency and self-efficacy among nonnative EFL teachers. System 2016, 58, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Teo, T.; Guo, J. Understanding English teachers’ non-volitional use of online teaching: A Chinese study. System 2021, 101, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Grade Level: Tracking Online Education in the United States; Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group, LLC. 2015. Available online: http://onlinelearningconsortium.org/read/survey-reports-2014/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Vivolo, J. Understanding and combating resistance to online learning. Sci. Prog. 2016, 99, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.; Steck, A. Changes in faculty perceptions about online instruction: Comparison of faculty groups from 2002 and 2016. J. Educ. Online 2019, 16, n2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, M.; Mukherjee, M. Tell me what you see: Pre-service teachers’ recognition of exemplary digital pedagogy. In Proceedings of the Australian Computers in Education Conference 2012; Australian Council for Computers in Education: Brunswick, VIC, Australia, 2012; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Justice, L.M.; Sawyer, B.; Tompkins, V. Exploring factors related to preschool teachers’ self-efficacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzberger, D.; Philipp, A.; Kunter, M. Predicting teachers’ instructional behaviors: The interplay between self-efficacy and intrinsic needs. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, A.M.; Giles, R.M. Preservice Teachers’ Technology Self-Efficacy. SRATE J. 2017, 26, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rodarte-Luna, B.; Sherry, A. Sex differences in the relation between statistics anxiety and cognitive/learning strategies. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 33, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.L. Assessing the relationship between student teachers’ computer attitudes and learning strategies in a developing country. Int. J. Quant. Res. Educ. 2013, 1, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frequency | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 Male | 61 | 20.8 |

| 2 Female | 232 | 79.2 | |

| Age | 1 25–35 | 68 | 23.2 |

| 2 36–45 | 141 | 48.1 | |

| 3 46–55 | 58 | 19.8 | |

| 4 Over 56 | 26 | 8.9 | |

| Teaching Year | 1 Under 5 years | 42 | 14.3 |

| 2 6–10 years | 41 | 14.0 | |

| 3 11–15 years | 68 | 23.2 | |

| 4 16–20 years | 54 | 18.4 | |

| 5 Over 20 years | 88 | 30.1 | |

| Title | 1 Teaching assistant | 32 | 10.9 |

| 2 Lecturer | 133 | 45.4 | |

| 3 Associate Professor | 96 | 32.8 | |

| 4 Professor | 32 | 10.9 | |

| Highest Degree | 1 Bachelor’s | 26 | 8.9 |

| 2 Master’s | 228 | 77.8 | |

| 3 PhD | 39 | 13.3 | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subscales | Adopted | Tested | |

| Behavioral Intention | 0.90 | 0.91 | |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.93 | 0.70 | |

| Student Engagement | 0.93 | 0.92 | |

| Instructional Strategies | 0.94 | 0.79 | |

| Classroom Management | 0.93 | 0.71 | |

| Computer Ability | 0.86 | 0.83 | |

| Items | Percent (%) | M | S.D. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (f) | (f) | (f) | (f) | (f) | |||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | |||

| I intend to conduct online teaching in my teaching practice in the future. | 2.0 (6) | 6.1 (18) | 32.1 (94) | 48.5 (142) | 11.3 (33) | 3.61 | 0.84 |

| I plan to conduct online teaching as much as possible in my teaching practice in the future. | 3.4 (10) | 18.4 (54) | 45.4 (133) | 26.3 (77) | 6.5 (19) | 3.13 | 0.91 |

| I will conduct online teaching regularly in my teaching practice in the future. | 2.7 (8) | 10.6 (31) | 28.0 (82) | 50.2 (147) | 8.5 (25) | 3.51 | 0.89 |

| I will conduct online teaching frequently in my teaching practice in the future. | 3.8 (11) | 24.6 (72) | 41.6 (122) | 23.9 (70) | 6.1 (18) | 3.04 | 0.94 |

| I will suggest that my colleagues conduct online teaching in their teaching practice. | 3.1 (9) | 18.4 (54) | 44.4 (130) | 28.3 (83) | 5.8 (17) | 3.15 | 0.90 |

| I would like to conduct online teaching rather than face-to-face teaching in my teaching practice. | 9.6 (28) | 40.6 (119) | 31.7 (93) | 14.0 (41) | 4.1 (12) | 2.62 | 0.98 |

| Overall | 3.18 | 0.76 | |||||

| Items | Percent (%) | Mean | S.D. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (f) | (f) | (f) | (f) | (f) | |||

| Nothing | A little | Some | Quite a Bit | A Great Deal | |||

| (SE11) How much can you do to help your students think critically in an online class? | 1.7 (5) | 15.7 (46) | 66.2 (194) | 14.7 (43) | 1.7 (5) | 2.99 | 0.66 |

| (SE12) How much can you do to motivate students who show little interest in online work? | 1.4 (4) | 17.4 (51) | 64.2 (188) | 15.4 (45) | 1.7 (5) | 2.99 | 0.67 |

| (SE13) How well can you structure an online course that facilitates collaborative learning? | 3.8 (11) | 14.3 (42) | 56.3 (165) | 21.5 (63) | 4.1 (12) | 3.08 | 0.82 |

| (SE14) How much can you do to get students to believe that they can do well in an online class? | 1.7 (5) | 16.7 (49) | 58.7 (172) | 20.1 (59) | 2.7 (8) | 3.05 | 0.74 |

| (SE15) How much can you do to control disruptive behavior in an online environment? | 1.4 (4) | 18.1 (53) | 59.7 (175) | 17.4 (51) | 3.4 (10) | 3.03 | 0.74 |

| (SE16) How much can you do to help students value learning online? | 1.4 (4) | 12.3 (36) | 61.1 (179) | 23.5 (69) | 1.7 (5) | 3.12 | 0.68 |

| (SE17) How much can you do to foster individual student creativity in an online course? | 1.7 (5) | 17.7 (52) | 62.5 (183) | 16.7 (49) | 1.4 (4) | 2.98 | 0.68 |

| (SE18) How much can you do to improve the understanding of a student who is failing an online class? | 1.4 (4) | 8.9 (26) | 59.4 (174) | 27.6 (81) | 2.7 (8) | 3.22 | 0.70 |

| (SE21) How much can you gauge students’ comprehension of what you have taught in an online course? | 17.4 (51) | 19.5 (57) | 21.2 (62) | 19.8 (58) | 22.2 (65) | 3.10 | 1.40 |

| (SE22) To what extent can you provide an alternative explanation when students in an online class seem to be confused? | 0.7 (2) | 1.4 (4) | 14 (41) | 51.9 (152) | 32.1 (94) | 4.13 | 0.75 |

| (SE23) How well can you structure an online course that provides good learning experiences for students? | 0.3 (1) | 2.4 (7) | 15.7 (46) | 54.9 (161) | 26.6 (78) | 4.05 | 0.74 |

| (SE24) How much can you adjust your online lessons for different learning styles? | 0.7 (2) | 1.7 (5) | 13.3 (39) | 47.4 (139) | 36.9 (108) | 4.18 | 0.78 |

| (SE25) How well can you respond to difficult questions from online students? | 2.4 (7) | 10.6 (31) | 21.8 (64) | 47.4 (139) | 17.7 (52) | 3.68 | 0.97 |

| (SE26) How well can you craft questions or assignments that require students to think by relating ideas to previous knowledge and experience? | 0.3 (1) | 0.7 (2) | 18.1 (53) | 48.1 (141) | 32.8 (96) | 4.12 | 0.74 |

| (SE27) How much can you do to use a variety of assessment strategies for an online course? | 0.7 (2) | 1.0 (3) | 15.7 (46) | 50.2 (147) | 32.4 (95) | 4.13 | 0.75 |

| (SE28) How well can you provide appropriate challenges for very capable students in an online environment? | 0.3 (1) | 2.7 (8) | 19.1 (56) | 48.1 (141) | 29.7 (87) | 4.04 | 0.79 |

| (SE31) How well can you develop an online course that facilitates student responsibility for online learning? | 2.4 (7) | 19.8 (58) | 60.4 (177) | 15.7 (46) | 1.7 (5) | 2.95 | 0.72 |

| (SE32) To what extent can you make your expectations clear about student behavior in an online class? | 1.0 (3) | 21.5 (63) | 56.0 (164) | 19.8 (58) | 1.7 (5) | 3.00 | 0.72 |

| (SE33) How well can you respond to defiant students in an online setting? | 9.2 (27) | 18.4 (54) | 35.5 (104) | 24.6 (72) | 12.3 (36) | 3.12 | 1.13 |

| (SE34) How well can you establish routines (facilitate or moderate student participation) in coursework so as to keep online activities running smoothly?) | 7.2 (21) | 23.5 (69) | 27.6 (81) | 27.6 (81) | 14 (41) | 3.18 | 1.15 |

| (SE35) How much can you do to get through to disengaged students in an online class? | 11.6 (34) | 19.8 (58) | 30.4 (89) | 22.9 (67) | 15.4 (45) | 3.10 | 1.22 |

| (SE36) How much can you do to get students to follow the established rules for assignments and deadlines during an online class? | 0.3 (1) | 2.7 (8) | 46.8 (137) | 43.3 (127) | 6.8 (20) | 3.54 | 0.68 |

| (SE37) How much can you control students dominating online discussions? | 1.0 (3) | 5.8 (17) | 61.1 (179) | 28.7 (84) | 3.4 (10) | 3.28 | 0.67 |

| (SE38) How well can you establish an online course (e.g., convey expectations, standards, course rules) for each group of students? | 1.0 (3) | 5.5 (16) | 61.1 (179) | 29.4 (86) | 3.1 (9) | 3.28 | 0.66 |

| (SE41) How well can you use the computer for word processing, internet searching, and e-mail communication? | 0.7 (2) | 3.4 (10) | 35.5 (104) | 46.1 (135) | 14.3 (42) | 3.70 | 0.78 |

| (SE42) To what extent does your comfort level with computers facilitate participation in online teaching? | 0.7 (2) | 2.7 (8) | 42.7 (125) | 44.7 (131) | 9.2 (27) | 3.59 | 0.72 |

| (SE43) How well can you navigate the internet to provide links and resources to students in an online course? | 1.4 (4) | 1.7 (5) | 37.9 (111) | 44.7 (131) | 14.3 (42) | 3.69 | 0.79 |

| (SE44) How well can you navigate the technical infrastructure of your institution to successfully create an online course? | 2.0 (6) | 10.9 (32) | 48.1 (141) | 32.8 (96) | 6.1 (18) | 3.30 | 0.82 |

| (SE45) How well can you navigate the technical infrastructure of your institution to successfully teach an established online course? | 1.4 (4) | 7.5 (22) | 52.2 (153) | 33.8 (99) | 5.1 (15) | 3.34 | 0.75 |

| (SE46) To what extent can you use asynchronous discussions to maximize interactions between students in an online course? | 5.1 (15) | 24.2 (71) | 52.9 (155) | 14.3 (42) | 3.4 (10) | 2.87 | 0.84 |

| (SE47) To what extent can you use synchronous discussion to maximize interactions between students in an online course? | 4.1 (12) | 19.5 (57) | 56.0 (164) | 16.7 (49) | 3.8 (11) | 2.97 | 0.82 |

| (SE48) To what extent can you use knowledge of copyright law to provide resources for online students? | 7.8 (23) | 26.3 (77) | 49.5 (145) | 12.6 (37) | 3.8 (11) | 2.78 | 0.90 |

| Overall | 3.19 | 0.49 | |||||

| Behavioral Intention | |

|---|---|

| Behavioral Intention | 1 |

| Student Engagement | 0.60 ** |

| Instructional Strategies | 0.51 ** |

| Classroom Management | 0.32 ** |

| Computer Capability | 0.47 ** |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.61 a | 0.37 | 0.36 | 42.30 | 0.000 b |

| Construct | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 0.173 | 0.321 | 0.537 | 0.592 | |

| Student Engagement | 0.689 | 0.093 | 0.519 | 7.427 | 0.000 |

| Instructional Strategies | 0.128 | 0.064 | 0.096 | 1.985 | 0.048 |

| Classroom Management | 0.016 | 0.080 | 0.011 | 0.199 | 0.843 |

| Computer Capability | 0.107 | 0.093 | 0.078 | 1.150 | 0.251 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Wong, S.L.; Khambari, M.N.M.; Noordin, N.b.; Geng, J. Assessing the Relationship between English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Their Acceptance of Online Teaching in the Chinese Context. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013434

Gao Y, Wong SL, Khambari MNM, Noordin Nb, Geng J. Assessing the Relationship between English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Their Acceptance of Online Teaching in the Chinese Context. Sustainability. 2022; 14(20):13434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013434

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yanjun, Su Luan Wong, Mas Nida Md. Khambari, Nooreen bt Noordin, and Jingxin Geng. 2022. "Assessing the Relationship between English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Their Acceptance of Online Teaching in the Chinese Context" Sustainability 14, no. 20: 13434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013434

APA StyleGao, Y., Wong, S. L., Khambari, M. N. M., Noordin, N. b., & Geng, J. (2022). Assessing the Relationship between English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Their Acceptance of Online Teaching in the Chinese Context. Sustainability, 14(20), 13434. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013434