1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

The emergence of craftwork can be roughly traced back to primitive societies [

1]. It is evident that many elements of culture are integrated into these crafts, whether it is the production process or their appearance (such as shape, color, or ornaments, etc.). We believe that crafts have unique characteristics that are not comparable to the mass-produced products of the 20th Century. Most crafts continue to be manufactured by hand, which is undoubtedly what makes them spiritual in nature. Furthermore, handicraft materials are sourced from nature, and they serve as a bridge between craftsmen and nature. Crafts of exceptional quality are also a true representation of a simple and unpretentious life. Culture plays an important role in the field of craft; through a variety of exquisite crafts, culture is promoted and maintained. Indeed, craftspeople play significant and important role.

However, people’s knowledge of crafts is still very limited, and they may be more familiar with mass-produced industrial products. Due to the disconnection or loss of craft skills, traditional crafts, which have been practiced for thousands of years, are facing a number of dilemmas today. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to consider the following question: What can be done to revive traditional crafts in the fast-paced and high-speed modern era, and how can they be made more sustainable? Considering the accumulation of research teams [

2,

3,

4], we used Taiwanese handicrafts as an entry point to explore this topic. In order to better carry out the analysis, based on the data and objective conditions obtained, our research focused on the field of bamboo weaving technology.

1.2. A Brief Review of Taiwanese Crafts

Modern design has a long history. Whether it originated in the United Kingdom and Continental Europe or later in the United States, Japan, and South Korea in the Far East, there are individuals who strive to protect, preserve, and promote traditional craftwork of the region. Examples include the Arts and Crafts Movement initiated by William Morris (1834~1896) in the United Kingdom, and

mingei by the Japanese craftsman Yanagi Sōetsu (1889~1961), and how it impacted later generations [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The Nordic design emphasis on combining traditional craftsmanship with modern design works by appealing to the philosophy of “coexist and prosper with nature” [

9,

10]. A major influence of the Bauhaus was its attitude towards crafts, which was profound and far-reaching [

11,

12,

13].

Culture has been described as “the way of life of the entire society” [

14,

15]. Lin [

2] points out that culture generally refers to patterns of human activity and the symbolic structures that give such activity significance. What’s more, culture is a lifestyle, and its formation gives birth to a taste of life through the life propositions of a group of people, and then forms a new “lifestyle” after being recognized by more and more people [

16]. Taiwan is one of the models of multicultural integration. Over time, this has created a unique cultural identity in Taiwan, which is also reflected in various crafts.

There is no doubt that traditional Chinese arts and crafts are very much alive and well in Taiwan. Taiwan is a multicultural blend of traditional Chinese culture with significant East Asian influences, including Japanese, and such Western influences as American, Spanish, and Dutch. This blend has allowed Taiwan, over time, to gradually develop its own distinct culture, mostly a variation on Chinese culture from outhern China. Taiwan has a unique advantage in the Chinese region as a result of its multi-cultural integration environment. Additionally, in recent years, the government has paid increasing attention to the protection and promotion of traditional culture, including various crafts [

17]. This has meant Taiwan’s craft industry has developed in an ideal environment. In Taiwan, when traditional crafts are discussed, they are represented by Yen Shui-long (1903~1997), who is considered the father of Taiwanese crafts (see

Figure 1).

We have gained insight into Taiwanese crafts through Shui-long’s various articles and books, which also explore the explore of how to further promote craftwork, both in light of the current situation and even how to globally expand it [

18,

19]. According to his article,

The Necessity of Taiwan’s “Craft Industry”, published in February 1942, Taiwan’s craft industry can develop under four favorable conditions [

18] (p. 19):

Taiwan is endowed with an abundance of natural raw materials.

There is a distinct style to Taiwanese crafts (e.g., various patterns or forms).

It is evident that the craftsmen and their children possess excellent skills.

There was a relatively low wage level at that time. In short, the craftsmen made crafts to sell, and the small amount of income they earned was used to supplement daily expenses.

The above statements describe the state of handicrafts in Taiwan 80 years ago. According to the study, the above statements need to be interpreted at a deeper level, or with different perspectives. Here are the details:

Taiwan has an abundance of natural raw materials, which is indeed an advantage, but it also needs to be integrated into the concept of sustainable development, rather than being blindly used.

Craftwork is closely related to Taiwan’s unique culture. This needs to be explored further.

The children of Shui-long’s time may already be masters now. Over the years, they have stuck to their fields and innovated further. They are more committed to the conservation and promotion of crafts. These people are highly valuable assets and represent the core values of Taiwanese crafts [

20].

This point may be controversial, and is one of the issues discussed in this article: In the absence of fair remuneration, it is difficult to encourage young people to engage in traditional crafts by relying solely on so-called ‘enthusiasm’. The question of how to formulate a reasonable remuneration, however, is not addressed in this article.

Fortunately, the development of Taiwanese crafts has entered a new era since the turn of the 21st Century. This provides Taiwanese craftworking the opportunity to reproduce its past elegance. On 2 January 2010, the National Taiwan Craft Research and Development Institute (NTCRI) was established, formerly known as the Nantou County Craft Research Class, established in 1954 (Shui-long was the first head of the agency). The NTCRI has always run initiatives for various exhibitions and workshops, giving more people the opportunity to understand the history and advantages of Taiwanese craftsmanship, and to participate in various forms. Furthermore, the NTCRI actively collaborates with various localities to organize workshops, invites craftsmen to make exquisite works on-site, and communicates with students and audiences. It has become evident that Taiwanese crafts have attracted growing interest and attention through academic studies, as well as various promotional activities, and this has become an important foundation for re-innovation and sustainable development.

1.3. Purpose

Taiwan’s crafts have a long history and distinctive characteristics. Indeed, craftworking faces many challenges, such as the lack of youth and new involvement and how to achieve sustainable development. Over the past few years, Taiwanese crafts have been promoted more frequently as a result of various activities being held. This not only increases the public awareness of Taiwanese crafts, but also affords the public an opportunity to observe and experience them closely.

Based on this context and the core issues mentioned above, and after repeated discussions by the authors, this study will analyze and discuss the following three issues:

In short, patience is of the utmost importance in the industry. However, due to the advanced age of many craftsmen and the lack of apprentices, many crafts are in danger of extinction. Thus, how do we promote the craft in order to attract more people to participate in it?

Although modern technology is capable of intervening in the form of digital collections, it is impossible to achieve truly achieve sustainable development solely through the use of technology. It is important to consider this issue in conjunction with the first issue.

Nevertheless, many people do not understand why a craft can be so expensive. There is an asymmetry of information behind this phenomenon: consumers do not understand the effort that craftsmen devote to their work, and the complex, even unique processes involved in the manufacturing of these crafts. Although price is not the sole criterion for measuring a work’s quality, for the craft to develop sustainably, economic benefits cannot be overlooked. Moreover, when the audience understands the complexity of the craft and the human touch involved in these crafts, they may not subjectively judge the crafts by the price, and they will also be willing to buy or collect the crafts at a reasonable price, which motivates the craftsman. The emergence of this mutually beneficial situation is also conducive to the sustainable development of crafts.

This study attempts to develop an academic model for enhancing communication between craftsmen and people, in the hope of providing a literature basis for the sustainable development of traditional crafts. In practice, the findings of this study can help craftsmen better develop their creations and consolidate their passions. Likewise, by re-prospering craftsmanship, it will increase people’s attention toward the practicalities of the sustainable development of crafts.

It is believed that sustainably developing craftsmanship requires the cooperation of craftsmen and the public. This is also the true meaning of handicrafts; from life, for life, and above life.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Humanity and Technology: The Human Touch of Crafts and Its Value

In spite of the fact that traditional craftsmanship often uses the simplest materials and construction methods, it is not simply a form of “tech/skill”, but instead a form of “culture”. This traditional handicraft has a special connection with the region or place in which it is located; it is the connection and bond between people and nature.

Almost all craftsmen strictly adhere to the rules of the past in their production process, which is not due to a reluctance to adopt new technologies. It is the persistence of these craftsmen that allows these crafts to maintain their most simple appearance. Through these rustic and exquisite crafts, we can gain a deeper understanding of their culture and philosophy of life. In the case of mass-produced industrial products, this may not be possible.

Yanagi [

21] believes that only those objects that are actually used in life are beautiful objects. This can also be understood from another perspective, in understanding Japanese aesthetics [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Yanagi also discovered beauty in everyday ordinary and utilitarian objects created by nameless and unknown craftsmen. According to Yanagi, utilitarian objects made by the common people are “beyond beauty and ugliness” [

21,

26,

27,

28].

In opposition to this, Shui-long’s approach to traditional craftsmanship is primarily based on economic considerations. In his analysis of traditional craftsmanship, Shui-long emphasizes the “aesthetics of practicality”, which means that crafting must respect the inherent beauty of the utensils, as well as the characteristic beauty of the materials used. In addition, it must be a craft that reflects the tastes of the time and integrates them into ordinary life [

18] (p. 25). Crafts are, in general, full of wisdom, and they are embedded in daily life in a seemingly simple way, and yet, despite playing a role, they convey a particular theme: the love of the mother or the view of the craftsman on the world. While industrial design incorporates the latest technology, it has been criticized for being too cold and lacking in temperature. We use the word ‘temperature’ here to illustrate that industrially designed products may not allow users to experience the craftsman’s influence within the product. In short, industrial products seem to lack humanity. In addition to being convenient, these products satisfy people’s desire in terms of fashion and style. There is no question that the “features” of these products are often soon replaced by a newer generation of products, and when the features of these products become obsolete, these products can be easily discarded. In contrast, crafts are durable and can last a lifetime.

Professor John G. Kreifldt of Tufts University has been engaged in the research of engineering psychology, human factors, and product design. The famous REACH toothbrush is one of his well-known achievements. However, he also has a keen interest and research interest in traditional culture and art. Kreifldt has unique insight into the products: “I not only value them for the money they may have cost but I also treasure and cherish them beyond their functions” [

29] (pp. 27–38). Kreifldt further states that, in fact, he also collects crafts from different cultures and materials from many countries and regions, and he likes to play with these collections. Every time he plays with these collections, he enjoys the feel of a piece of handicraft in his hand, as well as its visual appearance. Kreifldt states: “I also ‘feel’ a connection between my hands and the hands of the craftsmen. I ‘feel’ a spiritual connection with them” [

29] (p. 23). He also pointed out that it is only when the general public can appreciate the beauty of craftsmanship, and when people are willing to support craftsmen with practical actions, can we ensure that craft creation activities will be passed on.

Figure 2 shows a selection of the collection of crafts made by CHANG, Hsien-ping, who is known as a Living National Treasure. These crafts are hugely impressive and, whether as examples of exquisite skills or detailed representations, they are rustic and fascinating.

Audiences are often astonished by the exquisite crafts displayed in museums. However, people are interested but reluctant to experience the way in which we previously lived. What they lament is the story and connotations behind these artifacts. These artifacts are full of temperature; many collectors will take out their collections of utensils from time to time to play with and use, and when people touch these objects, it seems to create a sense of connection with a craftsman they have never met. This feeling is not given by modern industrial products; at least, there is a certain degree of difficulty. People may value mass-produced industrial products because they pay for them, but when a new generation of products comes out, people cannot seem to wait to dispose of the old ones, even if they are not obsolete. However, are handicrafts rarely found in this situation. For example, a childhood toy. It may not continue to be used, but the individual is reluctant to throw it away. This may be human nature at play. Essentially, these objects are full of memories and warmth.

2.2. Craft Creation and Its Dissemination and Cognition

There is a dialogue between the audience and craftsmen as they appreciate the crafts. The theory of communication can further explain this phenomenon. Briefly, the craftsman is the coder and the audience is the decoder.

Knowledge and understanding of the craft may be relatively limited among most people. However, these individuals are among the main beneficiaries of handicraft services. Alternatively, if people do not possess a good understanding of handicrafts (including their production process and cultural connotations), this will only increase the distance between people and craftsmen, which will negatively impact their survival and enthusiasm. Due to this, it is impossible to achieve the goal of sustainable development. Communication theory plays an important role in this process.

Hall [

30] proposed that audience members can play an active role in decoding messages, as they rely on their own social contexts, and might be capable of changing messages themselves through collective action. Fiske [

31] indicated that these codes “consist of both signs and rules that determine how and in what context these signs are used and how they can be combined to form more complex messages”. Decoding means that the message in which source has been encoded is interpreted by the decoder according to their own outlook and experience. The process of decoding involves the conversion of communication into thought.

Encoding and decoding are widely used in various fields of study [

30,

31,

32], and their mechanisms can also be applied to the interpretation of handicrafts. In this study, we believe that people’s ability to successfully ‘decode’ is an important aspect of communication.

Good communication is essential in helping the public better understand the ideas of craftsmen and the connotation of crafts. Handicrafts are expressions of the craftsman’s creative intention. Through this process, the craftsman’s imagination, thoughts, and feelings are reproduced. The purpose of these works is to implement ideas and expressions, and communicate them to the audience in order to ensure that there is an understanding between the craftsman and the audience [

33]. Craft creation is an expression of the craftsman’s pursuit of beauty. It has the following two inter-influencing characteristics:

“Crafts” has a “form” context that transforms abstract “connotation” into concrete “form”. Form (style) and connotation (idea) are different in expressing craft creation [

34]. How does the relationship between “intention” and “form” become the concept of creative thinking in crafts? There seems to be a certain degree of correspondence between “form” and “intention”, in that: to find clues to “connotation” in “intention”.

Past research on crafts creativity has mostly focused on the role of the craftsman, while paying little attention to the role of the viewer (decoder), yet the viewer plays an integral role in the complete craft process. An understanding of the cognitive processes involved in art or crafts appreciation can improve their ability to create stunning works of art. From the perspective of crafts and creativity, concepts and intelligence are an integral whole. Therefore, Norman’s [

35] three psychological concepts can be modified into three modes: the craftsman mode, the viewer/decoder mode, and the handicraft [

33]. The mode refers to the craftsman’s conceptual understanding of the work of craft. The viewer/decoder mode refers to the process by which they perceive the external aesthetics and internal meaning of crafts. Ideally, there is a high degree of congruity between the craftsman mode and the viewer/decoder mode, which allows the craftsman to effectively convey his/her message to the viewer by using language or symbols familiar to the viewer, and present them in a suitable context [

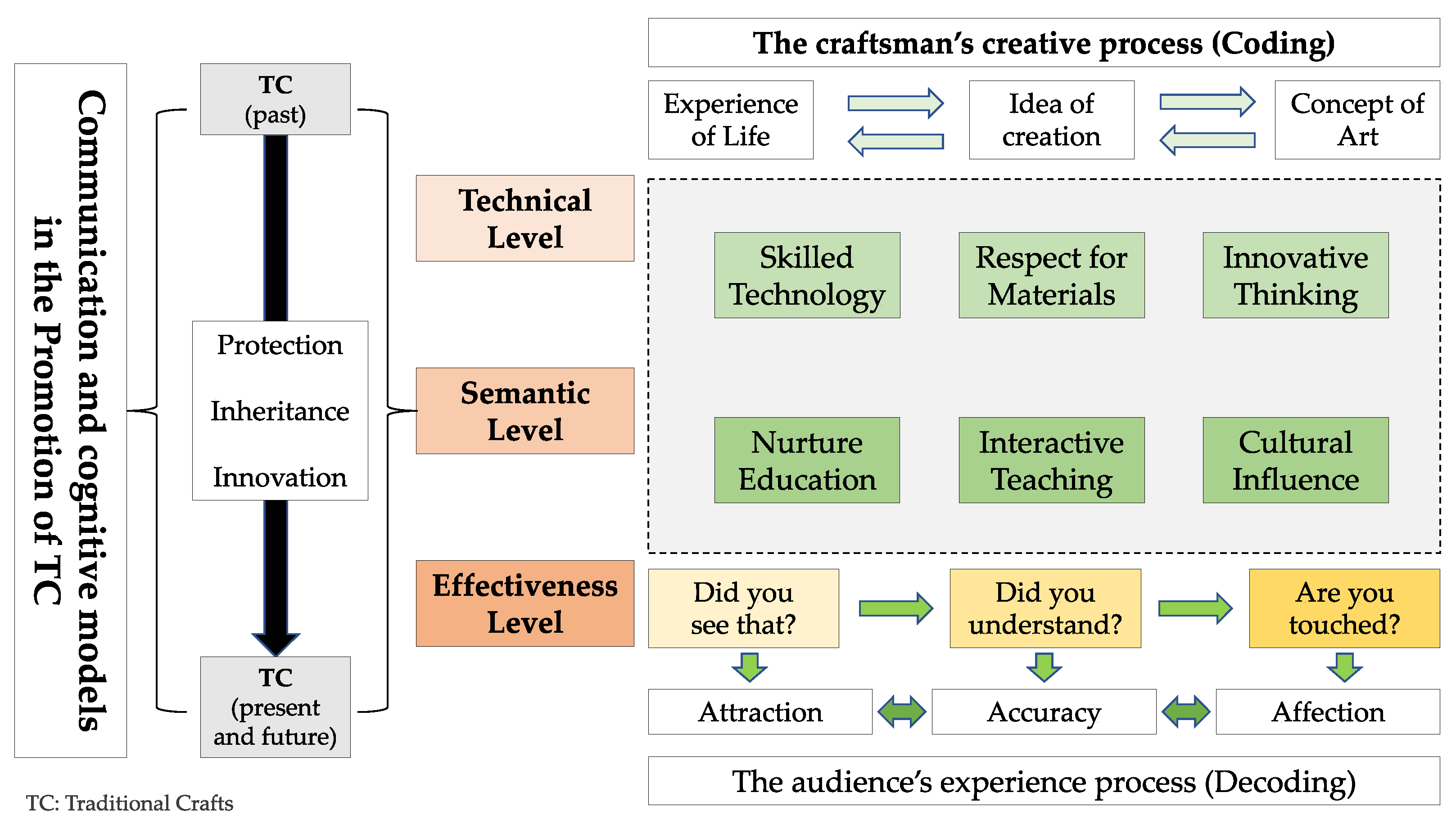

36]. The decoder perceives the external form at the technical level, then comprehends the inner meaning at the semantic level, and finally reaches the emotional connection at the effect level [

33,

37].

The promotion of traditional crafts requires collaboration between government officials and non-governmental organizations, as well as good communication between craftsmen and consumers. To accomplish this, a cognitive model or pathway must be constructed. The craftsmen are coders, and the audiences are decoders. Therefore, from the perspective of the “decoding” by the viewer, exploring the cognition of “crafts creation” is helpful for understanding the process of creation. Such principles and models also apply to our observation and evaluation of the crafts (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

3. Methodology

Taiwan’s handicrafts have received increased attention in recent years as a result of continuous efforts by the government, academia, and industry. In spite of this, there is still much to be discussed regarding how sustainable development can be achieved in a meaningful manner. It would be beneficial to conduct exploratory research on this issue.

It is usually appropriate to conduct exploratory research in order to investigate complex phenomena that have not been adequately explained [

38,

39]. At the exploratory stage, case studies are useful for gaining an understanding of the “why” and “how” of a problem. Based on a detailed description of the case situation and problem statement, data are collected and analyzed systematically in order to gain a better understanding of the phenomenon and context of the case [

40].

Semi-structured interviews are widely used in qualitative research [

41]. Considering the practical needs of open and exploratory topics, we used a semi-structured interview method, and every answer was verified by the interviewee. As a result, respondents were free to express themselves without being restricted in any way.

3.1. Conceptual Framework of the Case Study

The long history of Taiwanese crafts has left many treasures, some of which have been collected by various museums, while others continue to play an important role in daily life. A traditional craft is an aspect of culture and a cultural product. Cultural product design is a process of rethinking or reviewing cultural features, and then redefining them in order to design a new product that can fit into society and that can satisfy consumers culturally and aesthetically [

14]. It is important to integrate cultural characteristics into products to promote and preserve the culture of a region, as well as to increase the economic growth of society. In order to improve the cultural connotation of products, it is of great benefit to transfer cultural characteristics into them.

This study focused on the promotion of traditional crafts in Taiwan and, in addition to the relevant policies formulated by the government and the efforts of craftsmen, it is crucial for the audience to generate recognition. According to the procedural school of communication theory [

31], if the craftsman’s (sender/coder) signal is to be successfully communicated to the viewer (receiver/decoder), certain requirements must be met on three levels [

33]. Thus, for the purposes of this study, crafts promote cognitive processes, including:

On the technical level, the craftsman must accurately convey the message he/she intends to transmit so that the decoder can see, touch, and even feel it. (Did you see that?)

On the semantic level, the decoder needs to accurately understand the message being transmitted. (Did you understand?)

On the effectiveness level, the message needs to affect the decoder in such a way as to elicit a particular response or behavior. (Are you touched?)

For the audience to understand the cultural significance of crafts, three steps must be followed: (1) attracting their own attention (recognition); (2) generating correct cognition (understanding); and (3) forming deep emotions (reflection) [

2,

33,

37,

42,

43,

44]. In short: “recognition”, as a situational perception, indicates whether the craft appeals to the audience; “understanding”, as an artistic cognition, indicates whether the audience can understand the meaning of the message it conveys; “reflection” is a psychological feeling that indicates whether the audience can be moved in the process of viewing the craft.

Therefore, this study constructs a conceptual model to examine the communication process and cognitive patterns between craftsmen and audiences (see

Figure 5).

3.2. Procedures

A literature review is essential for clarifying the key concepts and values of craftsmanship, craft development, and inheritance, as well as interviewing masters who have been involved in the craft creation process for a considerable period of time. Due to COVID-19, face-to-face interviews were moderately reduced during the summer of 2022. Instead, telephone and email interviews were conducted.

3.3. Subjects

In many countries or regions, a Living National Treasure is a term for those individuals certified as Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Properties. It also includes many craftsmen. This honor is given to individuals who have made outstanding contributions to their fields over a long period of time and have already integrated craftsmanship into their daily lives. The exquisite crafts they produce display their ingenuity and wisdom, as well as their adherence and inheritance to the profession.

Furthermore, there are many craftsmen, and although they have not received similar honors at this time, this will not affect their creation and thoughtfulness in the slightest. This kind of recognition from people is also important to provide support for craftsmanship for a long time.

Based on this principle, this study selected three Taiwanese craftsmen who are well-known in the field of weaving. In addition, the authors have a close personal relationship with the three craftsmen. The three craftsmen have conducted their work for a long time, and hoped to share their views.

Table 1 provides the basic information pertaining to the three craftsmen. They have all been weaving for at least a few dozen years and have a wealth of experience, as well as their own unique and in-depth insights. Grandma Yang can be regarded as a living fossil of folk traditional crafts; Mr. Chang was awarded the honor of Living National Treasure by the Ministry of Culture; Ms. Su also recently received affirmation from the Nantou County Government. Therefore, their perspectives on craftsmanship are representative, to a certain extent, which is of great benefit to our in-depth understanding of traditional Taiwanese craftsmanship.

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the craftsmen and their masterpieces.

4. Result: Analysis and Discussions Based on Feedback Provided by the Subject

The three craftsmen selected by this study are all involved in weaving. Mat grass or bamboo are the materials that they use. In nature, mat grass and bamboo are simple and unpretentious. They can be transformed into exquisite crafts through the ingenuity and dexterity of craftsmen, and most have practical value and appear in daily life. In the authors’ view, this is one of the important connotations of the process. They use simple materials and changeable forms to create a unique aesthetic of life. At the same time, these crafts can also be used in life, or as ornaments for people to see.

The relationship between form and ritual in artifacts, which the authors explored in another study, can also be used to think about the value and meaning of crafts [

45]. In other words, if industrially designed products need to meet the function/high-tech, then crafts are closer to the level of feeling/high-touch.

In the next section, we discuss the feedback provided by the three craftsmen. It should be noted that their views may be subjective and may not be applicable to every field. These views, however, reflect the thinking of three craftsmen who have been working in the craft for many years. Therefore, we believe that they still have an important reference value, or can at least be used to stimulate further discussion.

4.1. From “Involuntary” to “Natural”: The Fusion of Craftsmanship and Life

Although many craftsmen were exposed to handicrafts in their early years, because of the economic conditions of their families, they were forced to produce some handicrafts for sale in order to supplement their family’s income. These difficult and necessary activities, however, became part of life and became natural as time passed.

In the opinion of the authors, this is also consistent with the purpose of the early establishment of different craft workshops. There is often a long and complicated process, it can be difficult to finance, and it may be difficult to maintain enthusiasm for a long period of time. As a result of holding various workshops, the government protects and inherits traditional crafts, but it also helps craftsmen to systematically master craft skills, which can then be exported overseas through government participation. Additionally, it will increase the popularity of Taiwanese handicrafts and benefit the craftsmen.

Today, the three craftsmen do not have to rely on crafts to support their families. Craftsmanship has been an integral part of their lives. As of this moment, they are more committed to preserving the inheritance of crafts, such as by recruiting apprentices, or by promoting traditional crafts in a variety of ways. It may be that the younger generation is curious about traditional crafts, or they may love them, but what is more important is how to guide them toward a deeper understanding of the craft and its culture. We may not care too much about sunlight, air, and water, but once they are no longer available, we become concerned. Although there is no attempt to elevate the process to such a high level; everything is about speed in this modern age of high-speed development. For example, life has been influenced by fast food culture for a long time. This implies that the integration of craftsmanship and life should not simply be a slogan or an aesthetic feature, but should have a deeper meaning.

4.2. Empty Cup Mentality: Keeping Pace with the Times Can Achieve Sustainable Development

One view has been stated as follows: In general, basic craft skills soon reach an advanced stage in many areas, and then remain, for a long time, unaltered. Even less subject to change, once established, was the basic existence of the professional craftsman [

46] (p. 41). In this study, the above statement is likely to be ambiguous, and may need to be amended in light of each individual situation.

The “unaltered” feature of craftworking mentioned here actually refers to the fact that a certain technique has been used by craftsmen so repeatedly that it becomes almost magical, and a habit. There is no need to change this feature. Moreover, for traditional crafts, following ancient methods is not equivalent to being conservative. In terms of the authors and the three craftsmen interviewed, we can be sure that the creative thinking of the craftsmen has changed. One concept that was proposed was: People have to be empty in order to be full. If people wish to learn more, they should begin by thinking of themselves as empty cups, rather than being complacent. Craftsmanship is fascinating, precisely because it gives a new look and life to seemingly ordinary materials. Following the production rules of the past is an attitude and a respect for craftsmanship. However, craftspeople are also willing to pay attention to popular trends and integrate various elements into their creations. These crafts are traditional on the inside, and many modern elements or styles can be seen on the outside.

The “empty cup mentality” is not to blindly deny the past, but to have an attitude that denies or empties the past, integrates into the new environment, and considers new work and new things. Strictly speaking, the three craftsmen in this study, whose are highly skilled and have accumulated decades of experience, said that they are number one. It is no exaggeration, and they are still very humble; treating every creation as a first.

Furthermore, they are often eager to learn new things, rather than become complacent. Grandma Yang, for example, continues to experiment with new weaving methods in her daily grass weaving. The authors used the summer to visit her home, and she mentioned that she is still learning to knit every day. The authors questioned this, asking why did she do this when she was already very skilled in weaving? She said: “The previous students have fallen behind, and we must learn what the young people are doing now?”. Her answer not only explains the approach of “living to learn from old age”, but also explains the true meaning of the “empty cup mentality”.

Craftsmen are constantly creating new works because of this mentality and belief. Handicraft has survived to this day thanks to the unremitting efforts of all craftsman. In order to achieve sustainable development, all individuals must work harder.

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

It has been a glorious century for Taiwanese craftsmanship, and its toughness and connotations have been well protected and are being increasingly recognized. Through the various craft exhibitions and workshops sponsored by either the government or individuals, continuous breakthroughs and innovations in Taiwanese crafts can be seen, as well as the visual feast generated by these refreshing crafts. Therefore, it can be concluded that Taiwanese craftsmanship has already developed in a fruitful manner, and continues to do so.

It is common for handicrafts to carry cultural traditions, and even a philosophy of life, associated with the people they represent. In some ways, the absence of culture may limit the high-quality development of society. The protection of handicrafts needs to be strengthened, as well as an exploration of ways in which they can be used to achieve an effective model of sustainable development. Additionally, contemporary handicrafts have taken on a variety of “forms” that differ from those of the past. The belief of the authors is that it is important to maintain the connotations of handicraft, and adhere to its key essence and spirit in order to highlight the principle of sustainability. Additionally, this will prevent handicrafts from becoming obsolete, and thus avoid losing their distinctive appeal.

Three aspects should be considered in order to achieve sustainable development:

Currently, there are few schools offering traditional craft departments, and most of them are in colleges and universities. One respondent suggested that the development of craft education may need to start small. It is possible that one does not need to learn too much technological skills at first, but time must be taken to allow a student to build aesthetic literacy.

- 2.

Establish the core essence of creative thinking: Keep pace with the times to make crafts continue to transform.

Innovation is the vitality of all things. In particular, traditional craftsmanship needs to stick to one side, such as some ancient methods of processing materials. However, it is more necessary for creators to have the ability to continue to innovate. This kind of innovation comes from the beauty of training since childhood, but it also depends on the empty cup mentality. In this way, we can continue to give new life to crafts.

- 3.

Integrate into daily life: Let crafts better reflect the true meaning of life.

Crafts can also be roughly divided into two categories: one is biased toward artworks, which are naturally expensive; the other needs to be grounded and close to life. For consumers, if the craft is too expensive and high-end, it may deter people. Crafts are derived from nature and used for life; this kind of handicraft not only causes the traditional style to reappear, but also meets with the modern aesthetic and people’s practical needs, which is doubly effective.

6. Limitations and Follow-Up Research

The authors were aware that exploring and discussing these three topics is not an easy task. Almost every topic can be written independently. As a pilot study, the research team tried to stimulate more people’s interest and attention to traditional handicrafts in Taiwan through this study, and jointly participated in the research of these topics.

Additionally, we only interviewed three craftsmen due to the limitations of the conditions, so there may be some omissions in the research findings and conclusions. It is our belief that, just as crafts have characteristics that are difficult to replicate, so too is the perspective of each craftsman. However, it must be verified in future studies whether these views can be generalized more broadly. In addition, we expect a growing number of people to pay attention to how Taiwan’s traditional crafts are now being reinterpreted in the modern age, providing a basis for sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Resources, writing—original draft, Y.S. and H.-Y.L.; Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was provided by the Start-up Fund for the Research of “Metasequoia Teachers” of Nanjing Forestry University under Grants No. 163103090.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanked the 3 craftsmen for their participation in the visit and allowed us to use their masterpieces free of charge. Their thinking on traditional craftsmanship has given us great inspiration. In addition, the authors would like to thank the National Taiwan Craft Research and Development Institute (NTCRI) for their support in the research process, in particular for allowing us to use the posters or related materials for its events.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Karppinen, S. Craft-art as a basis for human activity. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2008, 27, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R. Transforming Taiwan aboriginal cultural features into modern product design: A case study of a cross-cultural product design model. Int. J. Des. 2007, 1, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-L.; Chen, S.-J.; Hsiao, W.-H.; Lin, R. Cultural ergonomics in interactional and experiential design: Conceptual framework and case study of the Taiwanese twin cup. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-H.; Sun, Y.; Lin, P.-H.; Lin, R. Sustainable development in local culture industries: A case study of Taiwan Aboriginal communities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Imanishi, H. The sustainability of crafts: Shifting the paradigm of “Traditional Crafts”. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Convention of Asia Scholars (ICAS 12), Kyoto, Japan, 24–28 August 2021; pp. 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y. The myth of Yanagi’s originality: The formation of Mingei theory in its social and historical context. J. Des. Hist. 1994, 7, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, Y. A Japanese William Morris: Yanagi Soetsu and Mingei theory. JWMS 1997, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Moeran, B.D. Yanagi Muneyoshi and the Japanese folk craft movement. Asian Folk. Stud. 1981, 40, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Åhlberg, M.; Äänismaa, P.; Dillon, P. Education for sustainable living: Integrating theory, practice, design, and development. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2005, 49, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandinavian Design: How It’s a Way of Life and not just a Style. Available online: https://www.poshtel.live/scandinavian-style-how-its-a-way-of-life-and-not-just-a-style/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Bergdoll, B.; Dickerman, L. Bauhaus 1919–1933: Workshops for Modernity; The Museum of Modern Art: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mattil, E.L.; Scheidig, W. Crafts of the Bauhaus. Art Educ. 1968, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, F. The Bauhaus: Masters & Students by Themselves; Conran Octopus: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, M.C.; Lin, C.H.; Liu, Y.C. Some speculations on developing cultural commodities. J. Des. 1996, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, B.D.; Clark, H. Culture-based knowledge towards new design thinking and practice—A dialogue. Des. Issues 2003, 19, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R. The essence and research of cultural and creative industry. J. Des. 2011, 16, i–iv. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Hwang, S. An investigation on the learning mechanism of the sustainable management of local cultural institutes: A case study of Taiwan crafts workshops. Int. J. Learn. 2010, 17, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, S.-L. Formosa Industrial Art; Yuan-Liou Publishing Company: Taipei, Taiwan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-W. Taiwanese crafts movement of Yen Shui-Long and Yanagi Muneyoshi—The folk crafts (Mingei) in a comparative perspective. Arts Rev. 2008, 18, 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- LaVie. The Beauty of Touch: Aesthetic Experience from Hand to Heart; My House Publishing Co., Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi, S. The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty; Kodansha International: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, P. Japanese Design: Art, Aesthetics & Culture; Tuttle Publishing: Clarendon, VT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, Y. Japanese Modernisation and Mingei Theory: Cultural Nationalism and Oriental Orientalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, L. Wabi-Sabi: For Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers; imperfect publishing: Point Reyes, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, L. Wabi-Sabi: Further Thoughts; imperfect publishing: Point Reyes, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi Sōetsu. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yanagi_S%C5%8Detsu#Legacy (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Yanagi, S. Soetsu Yanagi: Selected Essays on Japanese Folk Crafts; Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagi, S. The Beauty of Everyday Things; Penguin: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, R.; Kreifeldt, J.G. Do Not Touch: Dialogues between Dechnology and Humart; National Taiwan University of Arts: New Taipei, Taiwan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Encoding and decoding in the television discourse. In CCCS Selected Working Papers; Gray, A., Campbell, J., Erickson, M., Hanson, S., Wood, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007; Volume 2, pp. 386–398. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, J. Introduction to Communication Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, R. Cognitive maps: Encoding and decoding information. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1989, 79, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Qian, F.; Wu, J.; Fang, W.; Jin, Y. A pilot study of communication matrix for evaluating artworks. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference, CCD 2017, Held as Part of the 19th HCI International Conference, HCII 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–14 July 2017; pp. 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Lee, S. Turning “Poetry” into “Painting”: The Sharing of Creative Experience; Taiwan University of Arts: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D.A. The Design of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. Language in Literature; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-L.; Chen, J.L.; Chen, S.J.; Lin, R. The cognition of turning poetry into painting. US China Educ. Rev. B 2015, 5, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 11th ed.; Thomson Wadsworth Publisher: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business: A Skill-Building Approach, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Son: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R.; Holland, J. What is Qualitative Interviewing? A&C Black: London, UK, 2013; pp. 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, R.T. Communication theory as a field. Commun. Theory 1999, 9, 119–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Hsieh, H.; Sun, M.; Gao, Y. From ideality to reality—A case study of Mondrian style. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference, CCD 2016, Held as Part of the 18th HCI International Conference, HCII 2016, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–22 July 2016; pp. 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, R. Elements of Semiology; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, I.-W.; Lin, R. Transforming “ritual cultural features” into “modern product forms”: A case study of ancient Chinese ritual vessels. Religions 2022, 13, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucie-Smith, E. The Story of Craft: The Craftsman’s Role in Society; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).