1. Introduction

In 1998 the last universal exhibition of the millennium—Expo’98—took place in Lisbon, which gave rise to an urban regeneration operation with strong impact in the city, particularly in its eastern part.

This dynamic was very frequent in the late 20th century: worldwide international events—Grand Projects as International Exhibitions, Olympic Games and others—were the pretext for urban regeneration processes that replaced entire deserted areas [

1,

2,

3] at their own expense (in Europe, often with the help of European Union programs). These events took place in the spirit of the aestheticisation of city life, which did not limit itself only to the disciplines of architecture and urbanism, but also extended to the visual arts.

Public art assumed an important role in those processes as a means of urban, economic and social development [

4]. Several cities hosted public art programs, attracting prestigious artists, either directly with art galleries or through commissioning, where “leading international artists and architects leave their mark on cities, generating new elements for their valuation in the context of global competition” [

4] (p. 26) (“artistas y arquitectos internacionales de primera línea dejan su marca en las ciudades, generando en el contexto de la competencia global nuevos elementos para su valorización”).

Frequently, those strategies happened in port cities, where their respective waterfronts had undergone relevant changes over time [

5,

6]. From the post-industrial period and due both to de-industrialisation and also to technological changes in maritime transportation, several spaces become empty, giving rise to deserted areas. Beginning in the last decades of the 20th century, great projects took place in those areas, which, despite their differences, seemed to have in common the aim of re-integrating waterfronts and the reclaiming of those areas for the use of citizens through the creation of new public spaces. In this context, waterfronts become privileged spaces for the exhibition of public art [

7]. In 2010, for example, there were 173 instances of public art on the Lisbon waterfront [

8]. In turn, the placement of public art becomes a way to intensify its symbolic nature and to emphasise its monumentalism. It is, however, important to remember that the monumentalisation of the waterfront is, in many cities, conflicting. As Kostof states, “the issue of monumentalising the water’s edges is complicated by functional arguments. To the extent that a river is a working watercourse with a port, there is a definite conflict between those who make use of it for trade-related activities and those who would turn into a work of art” [

9] (p. 41.)

In the context of those waterfront operations, specific programs for the implementation of public art were created to provide new public spaces with symbolic content. The experiences carried out in Barcelona were paradigmatic, both in the context of the Olympic Games, in 1992, and of Forum 2004. The Barcelona Universal Exhibition in 1888 had already been an example of the capacity of those events to catalyse public art for urban spaces—though the meaning of public art is here considerably different from the urban regeneration operations in the late 20th century. In fact, since the return to democracy, Barcelona initiated an entire process of urban regeneration, in different areas of the city and on different scales, from specific and targeted projects of public space design to Grand Event projects. Public art played an important role here [

10] as a means not only to develop the city’s identity and to dignify derelict spaces, but also to confer prestige to the new projects. Reflecting on the importance of public art, the initiatives of the Municipality of Barcelona for the creation of an archive of public art in collaboration with the University of Barcelona (through the Polis Research Center) and the Sistema d’Informació i Gestió de l’Art Públic de Barcelona [

11] are worth mentioning.

With the emergence of the theme of “returning the river to the city” in the end of the 1980s, and with the wave of new planning instruments from the 1990s, there was an awareness of the disadvantageous position of Lisbon’s eastern area compared to the western part of the city. This awareness culminated in the assembly of Expo’98 operation, which was taken as a pretext for rethinking the eastern zone and for rebalancing the city through the creation of a new centrality in it [

12]. After Expo’98, Lisbon’s waterfront was occupied by several artistic projects. In Lisbon, the port follows a linear occupation model [

13] and its infrastructures still occupy a substantial part of the 17-kilometre waterfront. Due to the inherently public character of public art, the placement of this art can be understood as an indicator of the areas where the port was interrupted, the “breaches interrupting this arid linearity and allowing an accessibility to the banks” [

14] (p. 112) (“brèches" interrompant ce linéaire aride et permettant une accessibilité des citadins aux berges”). That is to say, the public spaces that “conquer” the port system in a dialectic between functional/economic and leisure/symbolic values. In a more general understanding, public art projects can reveal, throughout the city, the areas of priority intervention at specific times, and Lisbon’s waterfront was certainly one of those.

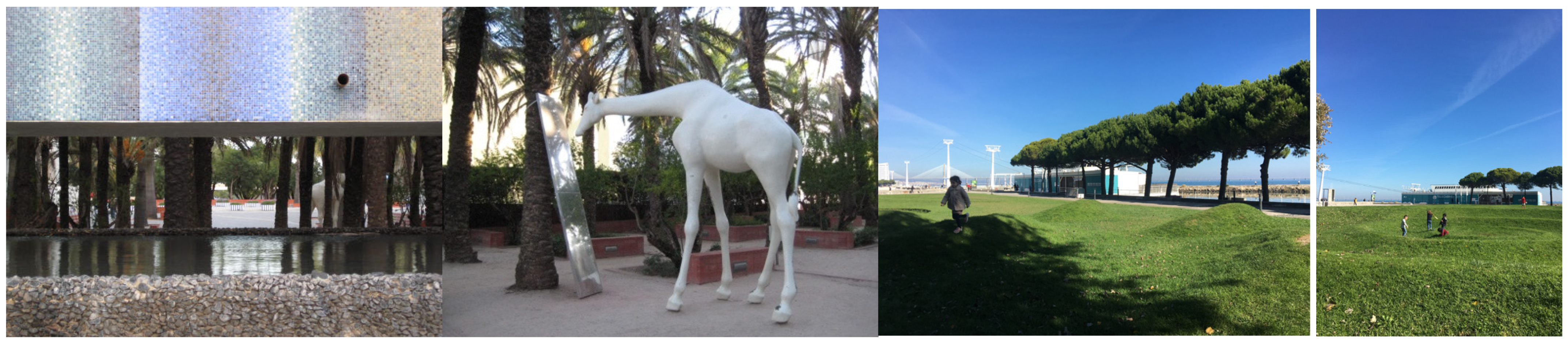

In parallel, after Expo’98, several projects took place along the waterfront, beginning with the initiative of diverse agents. With the motto “returning Tagus River to the inhabitants”, the Municipality of Lisbon enacted several transformations along its riverside spaces, including areas of leisure and water enjoyment, such as the “Parque Ribeirinho Oriente” (

Figure 1), a park by the river about 1.3 km long, following the area of Parque das Nações, the previous Expo’98 enclosure.

Along the waterfront some spaces of a cultural nature were also built, such as the Coach Museum (Paulo Mendes da Rocha + Bak Gordon Arquitectos, 2015), the MAAT—Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (Amanda Levete Architects, 2016), or the Champalimaud Foundation (Charles Correa, 2012); all of these projects were commissioned to architects of the international Star System. It is important to highlight that, if, on the one hand, this equipment includes space for the enjoyment of the river, in its external areas (which are not always free of access), on the other hand, it does not fail to cause a physical and visual barrier with the waterfront.

Also, extensive real estate projects were promoted where the relationship with the river was a factor of economic valuation, one of the most recent cases being the “Jardins do Braço de Prata” (Renzo Piano + CPU Urbanistas e Arquitectos) in the eastern part of Lisbon. This work dates from 1998 (contemporary to Expo’98) but was only recently built under the designation of the Prata Living Concept.

As we shall see, Expo’98 fundamentally had the merit of influencing urban policies in subsequent generations, being, for example, a laboratory for the Polis Program that took place in several Portuguese cities in the following years, but also influencing the way of approaching art and public space in urban contexts.

In view of this framework, this paper aims to discuss the relationship between public art and the dynamics of urban regeneration at the end of the 20th century. In addition, the paper intends to understand how public art relates to urban space, in terms of integration, but also in the experiences it generates and the appropriations it promotes. In this regard, this paper analyses: (1) Expo’98′s public art program, comparing its initial assumptions with the final results; and (2) the impact of this program, through the identification of the placement of public art before (1974–1998) and after (1999–2009) Expo’98.

2. Materials and Methods

Taking into account the aforementioned objectives, the research base of this article used two distinct methodological approaches:

To analyse Expo’98′s public art program, comparing its initial assumptions with the final results, (1) it was necessary to address a set of sources related to Expo’98’s public art programme [

15,

16,

17]. Document analysis (program excerpts and other publications by the curators) was the main methodology in this case.

To understand the impact of this program, through the identification of the placement of public art before (1974–1998) and after (1999–2009) the event, (2) this article used as a main basis the PhD Thesis Cidade e Frente de Água. Papel Articulador do Espaço Público [

8]. This work focused on the analysis of the physical, visual and symbolic relationships with water in port cities. This was achieved through: (i) the study of the main axes and respective public spaces that connect the waterfront with the inner city (in Lisbon and, as a counterpoint, in Barcelona), (ii) the analysis of the public art elements on those axes which generate symbolic relations with the water. In this work, the main methodological procedure was contact with the territory, the direct observation of space and its subsequent systematisation in a set of graphic and photographic elements. In the period between 2008 and 2010, 250 public art elements were identified. At this point, it is important to clarify that public art is here considered from an inclusive/open perspective. We reject the point of view of public art as an isolated object, restricted to common assumptions such as monuments, sculptures or statuary. Besides its aesthetic values, public art is understood as an urban fact, establishing physical and social relations with the urban environment. On the other hand, the concept of public art refers to all the elements that can monumentalise urban space; thus, it takes into account some urban features that, although they may not have been intentionally conceived as public art, can be perceived as such, therefore having gained value because of their symbolic features. In summary, whether intentional or unintentional, the concept of public art includes those elements that give symbolic value to urban space, monumentalising it. Of these 250 identified public art elements, 173 were situated in the territory defined as waterfront. In addition, two sources played an important role in the identification of public art: (i) the inventory developed under the Projecto Monere (integrated information and public art management system for Lisbon) [

18]; and (ii) the work Estatuária e escultura de Lisboa [

19] and its respective website. The information in this guide was later (2008) made available online by the Municipality of Lisbon (

www.lisboapatrimoniocultural.pt (accessed on 1 January 2022)) with an individualised analysis of the works, in a similar fashion to the already mentioned Sistema d’Informació i Gestió de l’Art Públic de Barcelona.

3. Discussion/Results

3.1. Assumptions and Results of Expo’98’s Public Art Program

The main theme of Expo’98 was “The Oceans, a Heritage for the Future”, celebrating Portuguese discoveries. As said before, the exhibition was a pretext for regenerating a vast slice of territory in Lisbon’s eastern area, which was characterised by an extensive range of deserted and unoccupied terrains and industrial spaces. It was intended to transform this area into a new centrality [

12] which was to remain after the end of the Exhibition Therefore, the developed urban plan (Plano de Urbanização da Zona de Intervenção da Expo’98” (PUZI), 15th July 1994) was not limited to the Expo’98 venue but included its surroundings and integrated a set of projects of cultural equipment, leisure areas and new housing. Another objective of the urbanisation plan was to reconnect the Tagus River with the city, through the creation of new public spaces along the water.

In parallel, the organisation in charge of Expo’98 decided to implement a set of public art projects to define those new spaces. A total of 24 national and international artists were invited and given freedom to design their artistic projects. This was clearly an opportunity to test new artistic project models in Lisbon’s public space.

The program was curated by António Manuel Pinto and António Mega Ferreira. The artistic works were developed along with the exhibition project, according to the needs of the individual projects. In fact, there was not exactly a defined program, “so, it is less a program than a list of projects that found their reason for being not in a specific sectoral strategy aimed at the visual arts but much more in their placement in space and in the discourse that would give shape to the Expo’98 venue” [

17] (p. 9) (“por isso ele é menos um programa que uma lista das intervenções que encontraram a sua razão de ser não numa estratégia sectorial específica destinada às artes visuais. Mas muito na sua concreta inserção no espaço e nos discursos que haveriam de dar corpo ao recinto da Expo’98”). Nevertheless, there was a common theme for the artists—the same one as that of the Exhibition—and many of the projects focused on the imagery of water.

In the proposals’ catalogue, António Manuel Pinto highlighted the possibility that the new spaces were conducive “to the most innovative urban experiences, beginning with the desire to introduce new philosophies of the use of space” [

17] (p. 13) (“às mais inovadoras experiências urbanas, partindo do desejo de concretizar novas filosofias de ocupação de espaço”). The importance of public art as a symbolic and site-specific issue was taken into account through an understanding of the work together with the location on an integrated level: “we have not merely moved existing works of art to a public place, nor is that what makes an artistic object into an object of public or urban art (…). An object of public art is specifically designed for that location” [

20] (p. 177) (“não nos limitámos a deslocar obras de arte existentes para um local público, nem é isso que torna o objecto artístico um objecto de arte pública ou urbana (…). Um objecto de arte pública é pensado de raiz para essa situação”). In addition, the strategies that were followed consisted of promoting relationships—through scale, framings and others—with the location: “there was a conversation with the artist in which the object was defined; we considered the height, the space where it will be placed, the way it would be seen from various points” [

19] (p. 21) (“Havia uma conversa com o artista em que se definia a peça, considerávamos a altura, o espaço onde se inseria, a forma como seria vista de vários sítios”). It was intended to explore physical but also social relationships, humanising the landscape and boosting urban experiences, “artistic projects that influenced the experiential use of the territory” [

17] (p. 13) (“projectos artísticos que influíssem nas práticas vivenciais do território”).

On the other hand, conventional models of art integration were questioned, namely, the model of statuary in the centre of a square. Public art was rejected as a bibelot—a decorative element or an accessory to the urban fabric [

16]—but rather understood as an artistic project promoting the experience of the territory, not only in sculptural projects but also in the design of new topographies, pavements and coatings, among others (

Figure 2).

Finally, it was intended to comprehend all the projects under a coherent logic. In addition to promoting relationships within its context, each work should be a point of reference in the urban fabric. According to António Mega Ferreira, the urban art program of Expo’98 “represents a sum of the parts that are indispensable elements for the construction of the landscape, not as decorative figures, but as

topoi of a strategy of deconstruction and reconstruction of urban space that culminates in the Expo’98 venue but inevitably extends throughout all the project zone” [

17] (p. 9) (“representa a soma de partes que se foram afigurando como elementos indispensáveis à construção da paisagem, não como figurações decorativas, mas como topoi de uma estratégia de desconstrução e reconstrução do espaço urbano que culmina no recinto da Expo’98 mas se prolonga, inevitavelmente por toda a zona de intervenção”) (

Figure 3).

Regarding the projects’ subject, one of the main concerns of the commissioners’ team was the relationship of urban art with the past, “We did not want an old-fashioned discourse (…) it was an interesting work: the integration of a strong component of urban art in new spaces, contrary to the temptation of filling it with references related to the history of Portugal” [

19] (p. 21) (“Não pretendíamos um discurso passadista (…) foi um trabalho interessante: integrar uma forte componente de arte urbana num espaço recém-nascido, sem cair na tentação de o rechear com referências à História de Portugal”).

In a context in which art in the public space was undervalued and quite limited both spatially and plastically, these assumptions favoured the commission of a set of projects that reflected the Portuguese artistic contemporaneity. However, this contemporaneity was limited to a restricted group of artists who, due to foreign experiences or influences, had broken with the art of the Estado Novo period. These were the names that were invited to this unique moment of recognition of Portuguese public sculpture [

21], that matched with the possibility of creating a public art project for the first time in Portugal.

However, despite the glow of the program’s initial assumptions, many of the solutions fell short of what was expected. In general, most of the artistic projects did not achieve the proposed objectives and did not surpass the character of space’s descriptivism [

22,

23]. Although this was a unique opportunity to question public art concepts, many of the results did not motivate any processes of spatial/social articulation with the urban context. In addition, many of them, though adopting a more contemporary language, were not beyond the model of statuary in the centre of a square that was so criticised.

Although the idea of site-specific art integration was developed in few situations, there were some examples that deeply explored the relationship with the environment, with urban context and with the water. From those, we shall mention the works “sem título” (Pedro Cabrita Reis) (

Figure 4), occurring around and under a viaduct next to the Expo’98 enclosure; or the work “Jardim das Ondas” (Fernanda Fragateiro + João Gomes da Silva) (

Figure 5), a set of gardens exploring different flexible space situations and promoting different types of space appropriation.

3.2. Expo’98’s Public Art Works in the Following Years

More than two decades after the Expo’98 event, the projects of the public art program still remain in their original locations. In 2015, maintenance works were carried out, through a protocol between the Municipality and the Parish Council of Parque das Nações, which also provided for a public art urban guide for residents and tourists. There was a temporary removal of some of the works and other equipment, such as water mirrors, gardens, benches or pavements.

Currently, it is interesting to look at these projects from the point of view of a posteriori appropriations (which can also be applied to the buildings of Expo’98, many of them used for functions different from those for which they were originally planned. For example, one of the pavilions dedicated to musical/cultural events, the “Pavilhão Atlântico”, was recently transformed into a vaccination centre, under the recent COVID pandemic). Of the implemented public art works, some have been actively appropriated, as the case of the work/sculpture “Kanimambo” (Ângela Ferreira) (

Figure 3), that can be used as a playground, or the sculpture “Cursive” (Amy Yoes) (

Figure 3) that is also used by children as a slide, but also as a urinal.

The opposite also occurs: objects that have lost their initial function, but have remained as a point of reference. This is the case of the North Gate of Expo’98 (Manuel Taínha) (

Figure 3). Although it no longer has its initial function of delimiting the exhibition, it was maintained in its original placement for its sculptural and striking character—a physical reference—but also as a memory—a symbolic reference.

The current appropriations of all those works show how the initial mission of Expo’98’s public art program, of promoting interactions with the users of those public spaces, is fulfilled or not. We can say that objects that can promote use, appropriation and empathic relationships with users seem to have better fulfilled those assumptions, as in the already mentioned examples. However, this is not what happens to most of the works, which have a closed and merely aesthetic character (contributing more to the sense of an outdoor art gallery and less to the sense of public art [

24]). In addition, many of these works even require high-cost maintenance, such as the “water volcanoes” in several Expo’98 spaces. We can conclude that the works that motivate multiple appropriations—the works that make sense in the concept of public art that is here defended—can better resist the passage of time.

3.3. Symbolic Impacts of Expo’98’s Public Art Program

Despite having fallen short of the expected results—especially regarding integration—, Expo’98’s public art program had the merit of encouraging debate about art and public space within in the Portuguese context and in Lisbon, specifically.

One of the strengths of Expo’98, also a cause of its success [

20], was the quality of the spaces, the gardens, the riverside promenade and its leisure spaces. At the same time, the public art program transformed the eastern waterfront into one of the most densely monumentalised areas in Lisbon [

8]. Therefore, it is interesting to observe an increase of artistic projects in the public space, in all the city, in the following years.

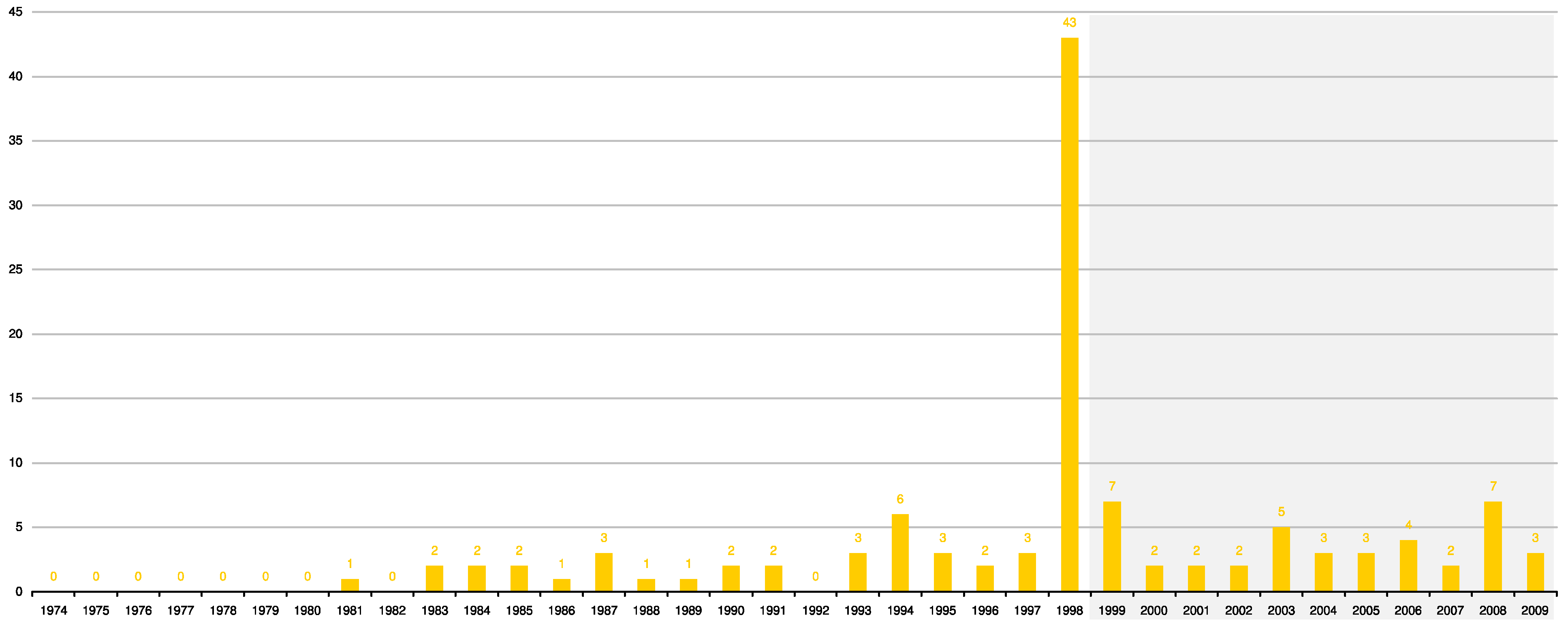

Figure 6 shows the placements of public art both in the waterfront and in the urban axes of articulation with the waterfront (the transverse axes) over 35 years, more precisely between 1974 and 2009 [

8].

Between 1974 and 1980, there were no public art placements. It is important to note that there may exist elements which are no longer in the public space. According to the defined rationale, only the elements that were in the studied spaces during the fieldwork period (2008–2010) were considered. The first identified work dates from 1981, the monument “Ao emigrante português”, next to the Santa Apolónia Railway Station, demonstrating the importance of this area in view of the remaining eastern riverfront, still a territory predominantly occupied by industries, port infrastructures and housing for the working class.

Between 1981 and 1997, there were between 1 and 3 placements per year, except for 1982 and 1992 without any placements, and 1994 with 6 placements—all in the western Lisbon, probably due to the event “Lisboa 94 Capital Europeia da Cultura”, which encompassed a vast artistic program and a set of cultural spaces.

As expected, 1998 was an exception in the placement of public art, with 43 new projects, most of them in the scope of Expo’98. The way public art was addressed and the results of the urban regeneration process—a new and highly densely monumentalised area—certainly gave an impulse to the placement of all those works in the post-Expo’98 period.

Between 1999 and 2009, there was a significant increase of public art: between 2 and 7 new elements per year. In all this period, there were 40 new placements, 19 in the western area/historical centre, and 21 in the eastern area of the city. Of these 21 placements, 16 were in Parque das Nações, specifically in the territory that hosted the Exhibition. As observed, until this event, the eastern part of Lisbon had very few examples of public art; currently, it is one of the most densely occupied areas in the city. However, there was no such increase in the surrounding areas, namely in Chelas or Olivais (Norte and Sul) neighbourhoods, which is symptomatic of the lack of contamination [

20] from Expo’98 to the rest of the eastern Lisbon.

3.4. Public Art in the Post Expo’98 Period—Themes and Placement

Among the 40 works placed on Lisbon’s waterfront and in the transverse axes in the decade of 1999–2009, there are several monuments focusing on emblematic themes and with strong symbolic character. Works such as “500 anos da partida de Pedro Álvares Cabral para o Brasil” (a celebration of the 500 years since Pedro Álvares Cabral’s departure to Brazil), “A guitarra portuguesa” (a tribute to the Fado singer Amália Rodrigues), or the work with the name of the city “Lisboa, aos construtores da cidade” (a tribute to all the city builders) had positions near the water. On the other hand, in the universe of those 40 public art elements, only 5 did not occupied the waterfront. Thus, it is possible to confirm that, beyond being privileged spaces for the placement of public art, waterfronts are also a context for monuments of important symbolic character.

It is also possible to understand that all those placements reflect a chronology of the projects on the Lisbon waterfront and the “openings” into the port system in that period. They also report the contemporary urban policies and the particular way of conceiving the city and public space in that period.

For example, in Parque das Nações, it is possible to identify a tendency to associate public art to buildings in various ways, such as in facades, in sculptures that stand out from the main volumes or in transitional spaces such as entrances, patios and terraces—physically accessible, but often not visible from the public space.

Although the impulse was given by Expo’98’s public art projects, this way of bringing art to private/inaccessible spaces or simply associated to buildings does not follow the same logic of the public art program in which the works should relate to urban design, public space and to the specificities of its contexts, particularly with the waterfront.

The logic of the placements of the 1999–2009 period in Parque das Nações also seem distinct from the logic of placements in the other areas of the city: in the first case, most of the works do not explore any relationship with the place nor do they have any commemorative character. There is even a tendency towards a more abstract language, distant from the concept of monument.

In the artistic works post Expo’98, it is possible to perceive an understanding of public art from an aesthetic point of view—of art in the public space and less of public art [

24]. Somehow, it is more elitist (it is symptomatic that most of the works have a more abstract language) not incorporating the relationship with the public space or, therefore, its public condition. On the contrary, these works settle in housing buildings, favouring access to artistic projects exclusively for their residents. This tendency of placing urban art in Parque das Nações is related to prestigious housing strategies, in the same line as the design of buildings by renowned architects. It is interesting to analyse what is mentioned in the Website of the Portal of Nations [

25]: “In Parque das Nações the art is in the streets, in the squares, in the gardens, under our feet. It is worth seeing the works of urban art that talented artists left in Parque up close, turning it into an open-air museum. Discover them step by step!” (“No Parque das Nações a arte está na rua, nas praças, nos jardins, debaixo dos nossos pés. Vale a pena ver de perto as obras de arte urbana que talentosos artistas deixaram no Parque, transformando-o num museu a céu aberto. Descubra-as passo a passo!”) (

Figure 7). The positioning of artistic elements in residential spaces, with little or any contact with the public space, perhaps subverts its own meaning as public art.

4. Conclusions

Though having generated a new centrality and the replacement of an extensive area of dilapidated spaces and buildings, Expo’98’s urban project had failures: its insularity [

26]; the lack of synergies with the surrounding areas, particularly with problematic contexts such as Chelas, or even Olivais; and the housing project aimed at social classes with greater purchasing power—a large private condominium [

27]—despite the general poor architectural quality. It was also criticised both for excessive density, and the lack of investment in more experimental models and ways of acting [

20].

In the field of public art, the program developed in the scope of Expo’98 gave rise to a monumentalisation of all these new areas, associating symbolic elements with spaces of water fruition. In addition, it played an important role in the way of understanding the city and public space that decisively influenced subsequent urban policies and projects.

However, most of the works did not explore the integration in space, which could have been achieved if it had been undertaken as a more consistent interdisciplinary work, a priori [

20]. With a few exceptions, the initially planned collaborative approach was not adopted in the design processes. As Campos Rosado concluded later (in [

20] p. 177), “the public art program we proposed for the entire area of project was not very new (…) it should have participated earlier on the level of the design of the spaces and in the detailed plan. Otherwise, the presence of art is very traditional—placing a piece in one location…” (“o programa de arte pública que propusemos, para toda a área de intervenção, não foi muito novo (…) deveria ter participado mais cedo em opções ao nível do desenho dos espaços e plano de pormenor. De outro modo, a presença da arte é muito tradicional – colocar uma peça num sítio…”).

In the decade after the event (1999–2009), there was an increase of artistic projects in the city, particularly on the waterfront. But many of those projects subverted the public logic, as they were confined to buildings and had the purpose of economically enhancing the housing projects. In fact, the projects of the post-Expo’98 period reflect a certain exhaustion of the previous policies and even of public art.

In recent years, the attention has been focused on the label of “urban art”, garnering a specialised and international audience and generating an important economic movement, especially if cities have a curating policy, as is the case of the actions of the Urban Art Gallery (GAU) in Lisbon [

4]. Despite the interest in these practices, in many cases there still does not exist in them an ability to provoke relationships with the place, and, again, the artistic projects exhaust themselves in their aesthetic component.

In the opening of new possibilities for public art, it is important to consider new ways of thinking and creating the city, in the first place, with the people who inhabit it. Then, the interveners on urban space—architects, planners, but also urban sociologists, anthropologists, and others—should work together with artists, in concert, perhaps leaving their comfort zone. Public art commissions should take into account these premises. Moreover, they should not give up more participatory and interdisciplinary models, where art can exist in an integrated way and not in a decorative role. The new possibilities of public art can arise from the intersection between the specificities that characterise them and the complexity of the relationships that define current urban life.