1. Introduction

Studies on poverty and poverty alleviation strategies can be found in various disciplines ranging from economics to entrepreneurship, business, and marketing. The focus of research is mainly on economically underdeveloped countries, which are often referred to as Base of the Pyramid (BoP) markets. The term BoP was coined by Prahalad and Hart (1999) to refer to the world’s poor populations, who earn less than US

$2000 a year and are located at the bottom tier of the income pyramid; these are also known as subsistence markets. Prahalad and his colleagues initiated discussions about how businesses can participate in poverty alleviation by serving BoP markets through financially profitable activities [

1,

2,

3]. Others have contended that participating in BoP projects not only benefits the poor but also enables firms (‘firm’ refers to business entities in developed markets) to achieve triple bottom line sustainability [

4,

5,

6] by improving the social performance of their supply chains [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

However, entering BoP markets is not straightforward due to the various challenges faced by firms in developing their BoP supply chains [

12]. Given the specific characteristics and institutional environments of BoP markets [

13], firms participating in BoP projects often encounter difficulties when involving the poor as suppliers, producers, distributors (known as BoP 2.0), or consumers (known as BoP 1.0). These difficulties are multi-layered and can be discussed from various perspectives. One paramount debate in this regard relates to the tenets of institutional theory, which is considered as an emerging theory in the supply chain management literature. Institutional theory argues that the legal, economic, and social systems constituting a business environment can impact firms’ strategies and behaviors [

14]. If some of these institutions are weak or missing (and drastically different to those of the firm), which is not uncommon in BoP markets, this will impede a firm’s ability to operate efficiently via its supply chain. As a result, it is crucial for firms participating in BoP projects to understand the institutional characteristics of the BoP markets in which their supply chains operate. Failure to do so results in unrealistic expectations and strategies/practices that are not fit for purpose.

In light of the above, the problem of engagement with BoP markets can be formulated as one that relates to different institutions operating at different supply chain echelons across the global operations. Firms need to appreciate that the “socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” [

15] (p. 574) that evaluate the legitimacy of their actions and behaviors are context-dependent. Busse et al. (2016) refer to this as legitimacy context (LC), highlighting the importance of the context-based understanding of legitimization, which should inform stakeholders’ judgments of firms’ (and the poor) behaviors. For example, many BoP markets are characterized by the absence of formal (regulative) institutions [

16] or what is known as institutional voids [

17], as well as the prevalence of informal (normative and cognitive) institutions. Such LCs are different from those of developed countries. Supply chain managers that plan to engage in BoP business must have a clear perspective of the LCs in BoP markets and their differences from traditional markets at the top of the pyramid, including the effects of these LCs on their functional operations [

18,

19]. Firms involved in BoP projects that are not adequately prepared to initiate appropriate changes in formulating their business strategies or adapting their business/supply chain processes [

20] will be more exposed to the risk of failure. Moreover, these firms might be punished by their stakeholders (e.g., NGOs, media) even if the firms’ suppliers in BoP markets comply with the institutional expectations of their own LC. That is why it is crucial that both research and practice pay greater attention to the notion of LC and its theorization in the BoP context.

The importance of the institutional environment has been highlighted in various domains, such as entrepreneurship [

18,

21,

22,

23], partnership and collaboration [

19,

23], network analysis [

19,

23], and value creation [

24]. However, there is scant research on supply chain-related issues in BoP markets from the perspective of LC. Further, the effects of the LC (and its characterization) on the key functions of the firm require further consideration. Most studies have taken a narrow view, focusing on a single function or stage of the supply chain [

25,

26] to offer insights regarding the implications of engagement with the poor, with a few exceptions [

27]. Nevertheless, these studies have given their attention primarily to BoP 1.0, where the poor act as consumers. Other roles that the poor can assume (as part of supply chain engagement), such as supplier, producer, and distributor, have been less explored [

28]. In light of such inadequacies in the literature, we attempt to develop an integrative model that encapsulates both the BoP 1.0 and BoP 2.0 approaches in characterizing the LCs of BoP markets and their implications for the supply chain functions of a firm. In this regard, we focus on the following supply chain functions: procurement, production, distribution (BoP 2.0), and sales (BoP 1.0). We address the following research questions:

How can the LCs of BoP markets characterized? and

What are the implications of this characterization for the supply chain functions of a firm?Our conceptual study seeks to contribute to the emerging discourse on BoP supply chain management by characterizing the LCs of BoP markets and linking them with the supply chain functions of a firm. We also advance the BoP literature by putting supply chain issues in the BoP context [

7,

27,

29]. While the BoP literature mostly considers the poor as consumers of manufactured products [

28], we motivate BoP research by discussing the involvement of the poor as co-creators of BoP initiatives. Lastly, we contribute to leveraging the notion of LC by drawing on institutional theory and explaining how the lack of regulative institutions in BoP markets serves firms when integrating the poor into their supply chain.

Our paper is structured as follows. First, we synthesize recent advances and ideas in the BoP literature in relation to supply chain functions and in light of institutional theory. In the subsequent sections, we critically review relevant studies to elaborate our initial framework and address the research questions. This involves the characterization and implications of LCs for the supply chain functions of firms. The paper concludes with a discussion of theoretical/practical contributions, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. BoP and Supply Chain Functions

There is extensive research focusing on supply chain functions, such as procurement, production, distribution, and marketing in developed economies or developed regions of developing economies (known as traditional markets). However, a huge market in economically underdeveloped regions—i.e., the BoP market—has received less attention in supply chain studies [

2,

25,

30]. In contrast to the developed economies, BoP markets are characterized by undeveloped formal and legal specifications and are isolated from mainstream markets [

21,

23,

25,

31,

32,

33]. This creates challenges and opportunities for the supply chain functions of the firm, and such deserves more attention from the mainstream supply chain research. Operating in the BoP market requires organizations to adapt their strategies for different supply chain functions as it becomes impractical to do business in markets surrounded by extreme poverty and heterogeneity [

27,

34] using the developed economy mindset. Designing supply chain functions that are compatible with the BoP market environment is a major challenge for organizations. In this context, it is important for firms to identify and assess gaps in the BoP institutional environment and ensuing implications for supply chain functions in order to create successful BoP supply chains [

27].

Firms can create both financial and social values by accessing the relatively untapped revenue streams at the BoP while controlling their operational costs through global supply chains [

35]. This allows for addressing social issues through large-scale poverty alleviation business projects. Poor farmers in the BoP market could be engaged in various business relationships across supply chain functions depending on the characteristics of the industry. Traditionally, the poor are only viewed as

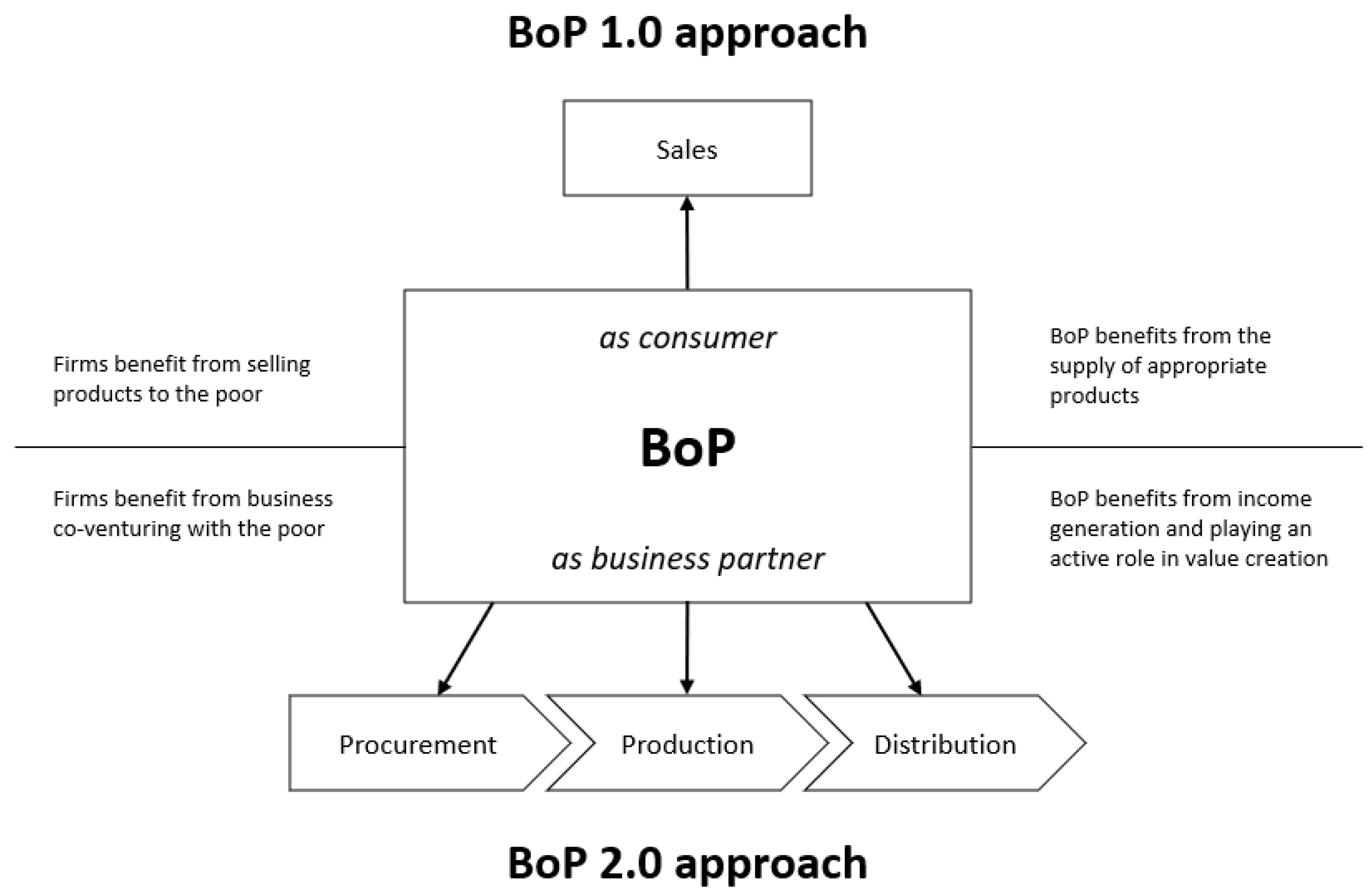

customers to whom firms supply products/services at affordable prices. In this model of operation, firms focus on fine-tuning their marketing/sales strategies to connect with the poor as their customer base. This consumption-based view of BoP markets is regarded as the BoP 1.0 approach [

7,

36,

37].

Recent research demonstrates that achieving greater business success and social impact at the BoP requires the integration of the poor in co-creation roles such as those of supplier, employee, and/or distributor [

9,

35,

38,

39,

40]. This rather integrative view of BoP markets is termed the BoP 2.0 approach [

37].

Figure 1 illustrates the two business approaches and their relationships with key supply chain functions.

Firms that solely engage with the poor via the BoP 1.0 approach may help to lessen the impact of poverty in the short run, yet this ‘arm’s length’ relationship will not offer them a chance to build trust through deep engagement and interaction at the BoP [

37]. In contrast, BoP 2.0 creates capacities for involving the poor in co-value creation activities as business partners, resulting in the development of collaborative relationships [

35,

41]. This also results in opportunities for greater social impact through the provision of employment opportunities and sustainable income for the poor. Regardless of which BoP approach is considered, it is important to highlight that while BoP markets offer firms significant leverage in their operations, supply chains are critical in connecting the poor to the global market in order to achieve sustainable progress toward poverty alleviation.

3. Institutions and LC in BoP Markets

Institutions are “multifaceted, durable social structures, made up of symbolic elements, social activities, and material resources” [

42] (p. 57) that elucidate the thoughts, behaviors, and interactions of social actors [

43,

44]. Regulative, normative, and cognitive characteristics of institutions [

42] represent the appropriateness, expectations, and basis for judgment of behaviors in that institution. Regulative institutions refer to “rule-setting, monitoring, and sanctioning activities” that create coercive pressure. Normative institutions “introduce a prescriptive, evaluative, and obligatory dimension” and render normative pressures. Finally, cognitive institutions are “shared conceptions that constitute the nature of social reality and the frames through which meaning is made” and, as such, develop mimetic pressure [

45] (pp. 52–57). Regulative institutions are also known as formal institutions, while normative and cognitive institutions are associated with informal institutions [

30]. All three sources of institutional pressures influence organizational actions and have a direct impact on decision making and formal structures [

44].

Institutionalists believe that markets are not only a system of economic and/or social interactions but also compound sets of formal and informal institutions that vary in different contexts [

14,

46]. These institutions have been identified as pre-requisites for market existence [

47], functioning, and development [

46], as well as enablers (or impediments) of market access and participation [

21,

48]. Thus, understanding the institutional aspects of a new market (such as BoP) would influence an organization’s business strategy, supply chain structure, and managerial decisions when entering the market [

14,

17].

According to the literature, a formal institution is defined as the rules, regulations, laws, and statutes that legally enforce the social acceptability of actions (such as contracts), while an informal institution refers to those values and norms that are not legally valid but support the social acceptability of actions and behaviors (such as strong traditional ties) [

14,

25]. A comparison of the institutions in BoP and non-BoP markets reveals that, unlike the primacy of formal (regulative) institutions in the latter category, BoP markets are characterized by strong informal (normative and cognitive) and weak formal institutions [

17,

19,

25,

33,

49]. These so-called “

institutional voids” in BoP markets are defined by Khanna and Palepu (1997, p. 41) as the lack of formal “

institutions that are necessary to support basic business operation”. Under this definition, institutional voids occur when the key market institutions are absent or weak.

It is important for firms that intend to work with the poor to appreciate the institutional set up in BoP markets, which is fueled by institutional voids, as shown in

Figure 2. This also means that firms’ (and their stakeholders’) decisions regarding strategies/practices across the supply chain functions must be informed by what is considered legitimate at the BoP (as opposed to their mainstream markets). The link between institutions and decisions (based on judgments) can be further understood by exploring the concept of legitimacy. Legitimacy is “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed systems of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” [

15] (p. 574). The subject of legitimacy in our paper includes strategies/practices associated with the supply chain functions of firms engaging with the poor. We argue that firms (and their stakeholders) draw on their subjective understanding of legitimacy to design the supply chain functions required for BoP business. The failure of BoP projects can ensue from differences between “contexts in which [firm’s and their stakeholders’ judgments] takes place” [

43] (p. 318). Differences between the firm’s own LC and that of the poor can be explored by drawing on the notion of institutional distance [

50]—that is, the extent of similarity or dissimilarity between the regulative, normative, and cognitive institutions of two contexts. In line with our research questions, we now turn our focus to characterizing the LC (and then its implications) at the BoP, drawing on the concept of institutional voids.

3.1. LC: Characterization

In order to characterize the LC of BoP markets, we reviewed various types of formal institutions that are necessary to support basic business operations. Our logic was that this allows for understanding the impact of institutional voids on the functional strategies/practices used by firms when entering BoP markets. In this regard, for example, Khanna and Palepu (1997) introduced five dimensions of formal institutions which are usually weak or absent in BoP markets: (1) capital market (limited financial options); (2) labor market (limited skills and knowledge); (3) product market (difficulty in assessing product attributes); (4) government regulation (difficulty in planning in an unstable regulatory climate); and (5) contract enforcement (difficulty in creating written agreements that can be enforced). The last two dimensions have been named macro-level institutions, while the others are named micro-level institutions [

32].

Similar to Khanna and Palepu’s (1997) work, Webb et al. (2010) categorized formal institutions as (1) capital market; (2) labor market; (3) infrastructure; (4) contracts; and (5) property rights and compared them between developed economies, developed regions of emerging economies, and BoP markets. In contrast to the situation in developed markets, Webb et al.’s (2010) study revealed that there is a lack of formal capital market and funds, an uneducated and low-skilled workforce, undeveloped infrastructure, informal governance mechanisms, and no property right protections in BoP markets. These limitations mean that firms cannot rely on the traditional strategies used in developed markets. Instead, they should employ strategies that are compatible with the LC of the new markets to ensure that the market mechanisms function effectively.

Our analysis of various discussions around formal institutional voids across the literature have resulted in characterizing the LCs of BoP markets into three broad categories: Governance, resources, and information. The governance LC includes the regulation, contract enforcement, and property right voids at the BoP. The resources LC comprises the labor market, capital market, and infrastructure voids, as well as the product market void related to the information LC.

Table 1 summarizes the three categories of LCs in BoP markets in terms of their definitions, reasons for occurrence, and related studies.

Various institutional voids across the governance, resource, and information LCs surrounding BoP markets provide a clear perspective of economic transactions with the poor and show that it will be subject to inadequate support from formal institutions due to the lack of an effective regulatory system for policy making, inappropriate infrastructure, and enforcement agencies [

23]. We argue that LCs that portray BoP markets do not necessarily carry negative connotations; instead, they can create opportunities for investment on behavioral levers and new forms of relationship-building activities. However, it is important for firms interested in launching BoP projects to identity LCs in the BoP markets of focus and assess the impact of voids therein on their supply chain functions. This enables developing corresponding (and BoP LC-based) strategies/practices to proactively manage challenges and seize opportunities to ultimately mitigate failure and improve the chances of success [

64], as elaborated next.

3.2. LC: Implications

3.2.1. LCs and Supply Chain Functions

In an established market, a firm can benefit from properly locating the decoupling point or the pull/push boundary of its supply chain. This would allow the firm to formulate its strategy and utilize its resources in such a way that efficiency in the push segment could be maximized while responsiveness in the pull segment could be enhanced to achieve the best result. This is based on the assumption that supply chain partners could work closely together for collaboration as a result of proper governance through contractual arrangements and trust [

65]. Consistency in supply chain operations in traditional markets to ensure continuous push/pull is basically a result of the primacy of rules, regulations, and laws that legally support activities and agreements between firms and supply chain actors [

62]. The practice of identifying and designing appropriate activities in supply chains to maximize performance is effectively implemented in developed markets; however, it will not be readily replicable in BoP markets. When firms decide to involve the poor in the supply chain as suppliers, producers, distributors, or customers, they need to consider the effects of LCs at the BoP on the design of their supply chain functions. The uncertainty and risk involved in working with BoP partners necessitate a different way of doing things in order to ensure that not are only social impacts delivered but also that financially profitability is achieved.

For example, if a firm that switches from local suppliers in a developed country to BoP markets, it may find maintaining reliable and long-term relationships with suppliers fundamentally different. In this regard, for example, a lack of contract enforcement tools can significantly increase supply risk due to the greater uncertainty in obtaining the secure and on-time supply of raw materials [

55]. Conversely, the same might offer opportunities to hone non-contractual skills for relationship building, such as the use of intermediaries or behavioral motivation techniques.

Similarly, a firm that plans to set up its production, distribution, and/or sales processes in BoP markets should be fully aware of the impact of the governance, resources, and information LCs at the BoP. Unclear government policies, corruption and bribery, and the lack of a transparent and effective legal system for enforcing contractual agreements in BoP markets effect capital investment decisions, such as the setting up of plants and distribution centers. Additionally, the selection of distributors and retailers should be made with a different set of variables, as this might make firms (and their stakeholders) hesitant to initiate BoP projects. This clearly demonstrates that when the LC at the BoP is not considered (and judged from the LCs of firms in a developed economy), BoP projects can be viewed as an additional pressure to the total cost of operation, which poses a formidable challenge for firms when making strategic decisions regarding supply chain design. This does not offer firms a realistic foundation to build upon, giving rise to the higher possibility of failure of BoP projects that are actually meant to create both profitability and social value.

Based on the above discussion, we put forward propositions regarding the influence of LCs on key supply chain functions (i.e., procurement, production, distribution, and sales). Our propositions highlight, respectively, how the LCs of BoP markets (and the institutional voids therein) impact firms’ strategies compared to those of developed and mature markets.

Figure 3 visually illustrates this concept in terms of the supply chain functions affected by the governance, resources, and information LCs of a BoP market. It also serves to represent areas that firms (and senior management) need to be more concerned with (and allocate resources for) when involving the poor in their supply chains.

3.2.2. LCs and Procurement

Sourcing from BoP producers can substantially contribute to poverty reduction [

9]. The LCs of BoP markets mean that firms should rethink their key procurement strategies/practices for identifying potential suppliers, working with them, and maintaining long-term relationships.

The resources LC at the BoP highlights the importance of developing capabilities for operating in resource-poor environments involving labor, capital, and infrastructure. Firms may have to deal with limited options to identify (and select) potential suppliers. Most producers and farmers in BoP markets are less educated and have little business knowledge [

66]. Such a situation restricts the number of suppliers who can correctly interpret the actual requirements of firms and supply reliably with the desired quality and quantity. Even if these suppliers are known to firms, the communication between the buyers and the suppliers will be subject to cultural distance [

54]. On other hand, the information LC of BoP markets signifies the need for innovative information capturing mechanisms to find qualified suppliers. This is because, for example, a lack of intermediaries who can introduce and provide information about potential suppliers and connect them with firms poses a challenge [

63].

A lack of contract enforcement mechanisms (governance LC) also means that procurement managers should focus on non-contractual levers that are aligned with the cultural and institutional environment of the poor. In this regard, an often-observed response from firms is drawing on short-term and transactional agreements as an entry strategy instead of focusing on long-term partnerships. The paradox here is that BoP suppliers desire long-term business and are unwilling to entertain short-term contracts with multiple firms largely due to the lack of market security and financial reliability [

55]. Such tensions (which arise from less attention being given to the LC at the BoP by firms) might lead to a deadlock if a mutually acceptable solution cannot be achieved.

3.2.3. LCs and Production

The lack of skilled labor (resources LC) in BoP markets requires the use of production-related strategies/practices based on, for example, the simplification of products (e.g., limiting features and flexibility and focusing on core functioning) [

17,

67]. The more complex the production process becomes, the more firms need to ensure that the corresponding expertise, knowledge, and skills can be provided at the BoP, which appears to be a challenging undertaking. Even if firms are willing to provide the required training for the BoP workforce, their low level of literacy can render this option impractical [

58]. Moreover, the rigid employment laws in BoP markets often prevent firms from making adjustments in the production workforce [

17]. As a result, this limits the ability of the firms to improve their workforce’s efficiency and effectiveness. These are important issues that need to be considered when producing in BoP markets and will require firms to re-organize production processes, such as postponing (or eliminating) aspects of the production to outside the BoP.

The instability of government policies, ineffective regulation systems, and corrupt political situations (governance LC) demand the use of different set of buffers and risk strategies for long-term production at the BoP. Rules can be unpredictably changed by local governments, and firms might be exposed to corruption [

68] and human rights concerns. Furthermore, the absence of rules that protect foreign investments, such as property rights, appropriate tax structures, and bankruptcy laws at the BoP, can increase transaction costs for firms desiring to set up operations and productions in BoP markets [

18,

23]. Such factors will allow firms to invest in the proper understanding of the regulatory environment at the BoP and financial and labor practices that, though they might be viewed negatively in the Western world, are considered legitimate when seen from the BoP LC. An example of this is child labor, which can be a necessity at the BoP and, while not ideal but accepted by the BoP LC. Such labor practice however poses a serious risk for firms operating in developed/emerging markets. Busse et al. (2016) explain how such dynamics might cause firms to experience extensive scrutiny and punishment by their stakeholders while, in reality, their BoP partners (according to the BoP LC) might not be violating their local laws.

3.2.4. LCs and Distribution

The poor and inadequate infrastructure (resources LC) in BoP markets has caused firms to realize that the use of traditional distribution methods will create more challenges for their operations [

2,

69]. This is exacerbated when considering access for the poor in BoP markets, as they are normally situated in remote and rural areas. Therefore, in these contexts firms face both infrastructural and access issues that require careful consideration.

While there may be some developed infrastructure in parts of BoP markets, this is usually insufficient for efficient distribution processes considering firms’ established distribution channels. A key implication of this is that firms should find ways to access qualified and motivated distributors who offer their services in remote areas. This has resulted in micro-distribution initiatives (e.g., local dispatch, direct selling, bike delivery, piggyback) becoming prevalent at the BoP. The high level of illiteracy (resources LC) in BoP markets [

67], which affects availability of people with specialized skills, also reinforces the idea that complex modes of delivery that require sophisticated planning are not fit for purpose in BoP markets [

57,

58].

Another area that requires effective management is how to ensure that the BoP distributors fulfil their obligations and maintain long-term relationships with firms. This needs to be considered in light of the LC of the BoP markets, as formal written agreements and legal enforcement (governance LC) may be limited. For localized informal agreements that might be enforceable within the communities involved [

30], firms will need to develop mechanisms that allow them to manage their distributors to cater for efficiency and responsiveness.

3.2.5. LCs and Sales

Families and individuals in BoP markets are very low-income consumers, with most of them having to spend their daily wages on meeting basic needs [

58]. Thus, firms taking the BoP 1.0 approach, which focuses on selling products/services to poor consumers, are constrained by affordability in terms of price and acceptability in terms of quality [

12,

69]. To promote products/services and their benefits in BoP markets, firms need to communicate with potential consumers. The lack of literacy in BoP makes it difficult to derive or maximize the value of the information provided by firms (or retailers) through marketing campaigns (information LC).

Increasing consumers’ awareness of the value of products/services requires adequate communication infrastructure and advertising facilities. In BoP markets, many customers do not have access to advertising media such as newspapers, magazines, or television, let alone Internet or social media. Information sharing is primarily conducted through face-to-face communication, but there is a lack of local information providers linking firms and communities [

56,

57]. As such, providing the necessary information about product attributes to potential customers to induce them to buy demands a radical change in marketing campaigns and strategies.

In relation to contract enforcement (governance LC) against BoP retailers, firms must review a number of issues. For example, ensuring that retailers will abide by certain pricing schemes and pre-determined promotion plans is an issue that is traditionally managed via contracts, yet the LC at the BoP calls for the use of trust-based and personalized social levers [

27].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, we sought to contribute to the emerging discourse on BoP supply chain management by characterizing the LC of BoP markets and linking it with the supply chain functions of a firm. Specifically, we addressed the questions of

How can the LCs of BoP markets be characterized? And

What are the implications of this characterization for the supply chain functions of a firm? Underpinned by institutional theory, we described how the LC of BoP markets can be characterized in terms of governance, information, and resources LCs (and the institutional voids therein). We also elaborated on the implications of the identified LCs for designing the supply chain functions (i.e., procurement, production, distribution, and sales) of firms entering the BoP market. Our study paves the way for theory-building efforts in the emerging area of BoP supply chain management in general and the LC at the BoP in particular [

7,

29].

As illustrated in

Figure 3, we maintain that firms need to adapt their supply chain functions in response to difficulties in identifying and developing suppliers as well as securing long-term supply at the BoP. We discuss this by characterizing the LCs of BoP markets and arguing that firms often use their own (developed economy) LCs for designing supply chain functions at the BoP, which diminishes the chance of success of their BoP projects. For firms with production operations in BoP markets who recruit local people as employees, the impact of formal institutional voids can be manifested in terms of finding skilled labors, planning for long-term production, and providing the required equipment. For firms involving local BoP people as the distributors of their products, underdeveloped (or non-existent) distribution channels, a lack of qualified distributors, and difficulty in managing long-term relationships with distributors are among the factors that construct the BoP LCs. In relation to firms selling their products to BoP markets, the lack of formal institutions in terms of effective information sharing and enforceable contracts can pose difficulties in identifying (and communicating with) potential customers and establishing long-lasting relationships with retailers.

To create effective supply chain functions in BoP markets and achieve the promises of BoP business, various formal institutional voids commonly found in BoP markets should be embraced by firms as the working legitimacy framework informing their decisions. It is also important for firms to carefully undertake cost/benefit analyses in relation to their preferred mode of operation at the BoP. In BoP 1.0, by looking at the poor purely as customers and, in BoP 2.0, by considering the poor as suppliers, the employees or distributors of the supply chain thus form an integral part of the value creation process. We explain that firms leveraging BoP markets as their source of supply might not be able to implement their procurement strategies in the same way as they do in developed markets. This is due to the uniqueness of the local institutional environment and the existence of formal institutional voids (e.g., labor market, product market, and contracting voids) that should not be merely viewed as obstacles. Instead, we argue that such LCs must be better understood, assessed, and used as a platform for creating new innovations [

70].

Our study contributes to the theory in this area by answering the recent calls for linking supply chain-related issues to the BoP literature [

7,

29,

63,

71]. We explain the need for aligning supply chain functions with the institutional environment surrounding BoP markets, and explored the function-specific challenges (and opportunities) that firms entering BoP markets have to evaluate using the BoP LC. Our study extends debates centered on institutional characteristics into an understanding of BoP supply chains and how they differ from traditional operations. Therefore, by describing the various formal institutional voids in BoP markets and their impacts on supply chain functions, we link the literature on supply chain management, BoP business, and institutions and highlight the role of supply chain management for poverty alleviation [

27,

63].

Responding to the call of scholars regarding the involvement of the poor in the value creation process [

8,

72], this study provides guidance for firms taking the BoP 2.0 approach that are willing to engage the poor in their supply chains either as suppliers, employees, or distributors. Practitioners and firms participating in BoP projects are able to analyze the target markets and understand their specific LC to identify the various voids and their unique impacts on each supply chain function when involving the poor in operations.

Finally, our study extends the application of institutional theory through studying formal institutional voids and their impact on supply chain functions. This is achieved by challenging the common view of institutions as efficient structures for facilitating activities [

73] with the premise that evaluating the LC enables firms to better appreciate what is considered legitimate (or not) outside their own operating environment. We characterize LCs and elaborated their implications to highlight opportunities for learning and honing skills for operating under resource-poor conditions. We believe that the literature on frugal innovation and even lean principles might be informed by capturing new business models [

74,

75] used by firms with extensive BoP operations. Our study also helps the stakeholders of firms to obtain a more realistic view of firms’ engagement at the BoP and shows that the LCs of BoP markets and their characterization are very different from those of developed countries.

Certain limitations of our study offer important leads for future research. Our work is conceptual, relying on existing theory and the literature to develop an initial framework (

Figure 2) and then elaborate it (

Figure 3). This paves the way for empirical studies that can expand and validate our contentions. For example, data can be collected through interviews and archival data using grounded theory and case study [

76] methodologies to study firms who have used both of the BoP approaches and key supply chain functions in various BoP markets.

It is important to note that firms entering BoP markets may experience unique supply chain challenges (and opportunities) and may hence require specific innovation strategies to apply their business model within these markets. A direction for future research is further exploring how firms deal with the supply chain challenges identified in our study and manage their procurement, production, distribution, and sales in BoP markets. In-depth investigations focused on specific sectors or supply chain functions will be fruitful. Finally, we believe that future research should compare the supply chain structures of firms in various BoP markets to understand the impacts of different LCs within different BoP markets.