1. Introduction

Cultural landscape is a term which entered geographical literature in the 19th century. Carl Ritter appears to have been the first to use

Culturlandschaft, in 1832. He was followed by Carl Vogel in 1851, Joseph Wimmer in 1882 and 1885 and Friedrich Ratzel in 1893 [

1]. Since then, it has been subject to international research and various issues related to it have been studied by German, French, American and other scientists, who focused on different aspects of this phenomenon. For instance, the German researchers looked into its evolution and visual aspects, while the French tried to identify specific relations between human activities and the environment, which are depicted in different forms of landscapes. In the USA, a cultural landscape was perceived as an inseparable whole and as not being divided into natural and anthropogenic components [

2]. In 1925, C. Sauer was the first to transfer Ritter’s

Culturlandschaft into the English-language geographical literature and defined a cultural landscape as a natural landscape that had been modified by a cultural group [

3]. In the Polish literature of the 20th century, a cultural landscape was not equated to a region [

4], and several additional terms related to this phenomenon emerged, e.g., cultural environment [

5,

6] or cultural space [

7].

Since unconditional growth and development in conjunction with environmental degradation stimulated a global commitment to landscape preservation, many studies addressing protecting the cultural environment have been published, e.g., works by Rössler [

8], Moore & Whelan [

9], Blake [

10] and Logan [

11].

Cultural landscape is one of three basic types of landscape mentioned by Buchwald & Engelhard [

12] in the context of anthropogenic pressures on the environment. Such a landscape is a result of civilisational development, and it is constantly undergoing changes. Moreover, the level of its anthropogenic transformation is so high that it cannot survive without human intervention. In a case when human actions do not devastate the environment or when a natural landscape is changed negligibly, it may be called a harmonic cultural landscape. On the other hand, when the intervention leads to degradation, such a landscape is called disharmonic [

13]. However, both types of cultural landscape may be a tourist attraction for different forms of tourism (e.g., harmonic cultural landscape for ecotourism [

14] and disharmonic for industrial tourism [

15]). Each and every form of tourism is based on interaction with landscape—as a whole or with its particular elements, which constitute separate tourist attractions. Thus, in tourism, landscapes are both subjects and objects of cognition and their attraction should be perceived holistically, not only as a simple sum of attractiveness of particular objects. Additionally, diversity and conservation status are other features of landscapes that influence their attractiveness to tourists [

13]. According to M. Antrop, the so-called “traditional landscape” is the most attractive to tourists. It is a product of slow evolutionary processes and has a clear structure that depicts a unique harmony of biotic, abiotic and cultural elements. Identity is a distinctive feature of traditional landscapes, and it also affects their attractiveness to tourists [

16]. Traditional landscapes are usually found in rural areas, and the impacts of tourism initiatives on their cultural landscape sustainability, as well as challenges for their conservation, are broadly discussed in the literature. There are both case studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21] and theoretical papers [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] providing guidelines and recommendations concerning the development of tourism products based on the cultural heritage of traditional landscapes, including their tangible and intangible elements.

In the 1970s, Pierce Lewis formulated some fundamental theses on cultural landscape and ways of its interpretation. According to these theses, each and every cultural landscape is a unique trace left by a certain group of people—it is a reflection of their activeness, a unique archive of their culture. In this context, the landscape can be deciphered and interpreted, providing knowledge on the societies that shaped it. Moreover, Lewis claims that all elements that a given landscape consists of are equally important and should be studied with the same commitment and dedication. Cultural landscape is a kind of biography which has been unconsciously created by the people living in a given region. The landscape reflects not only their preferences, tastes, values and aspirations, but also their fears and prejudices—they all take objectively existing spatial forms [

27]. A French geographer, Paul Vidal de la Blanche, also perceived culture as a source of ideas, values, beliefs and traditions which are all the basis for a destructive or creative approach to the natural environment surrounding human beings. According to de la Blache’s concept, the external environment (milieu externe) determines boundaries for human actions while the system of values and ideas (fmilieu interne) sets dynamics and directions of those actions. The cultural landscape (fpaisage humanise) emerges at the melting point of milieu and the so-called style of living (genre de vie), and it reflects the way that particular groups of people interpret and use their environment. P. Vidal de la Blache also claimed that the landscape is a result of history and culture, which both determine ways of life and relations between humans and nature [

28]. Similarly, G. C. Hoomans defined cultural landscape as a recorded history of a particular group of people coping with specific natural conditions. The impact that they have on the landscape is visible in geographic names, visual symbols and structures [

29,

30]. However, as N. Mitchell states, “[…] the complex array of cultural and natural values represented by tangible and intangible heritage are not readily understood by the outside visitor or manager. Understanding requires honoring the world-views and core values of the communities that are (or were) their stewards over different periods, listening to diverse voices and perspectives, and respecting the different knowledge systems and practices embedded in these places, which have much to teach us about resilience” [

31] (p. 117).

What is more, as K. W. Butzer claims, cultural landscapes mirror moral norms which are accepted and recognized by given societies. However, understanding such complicated systems, consisting of both symbolical and objectively existing elements, requires recognizing the values, life style and ways of perceiving the world adopted by a group or groups living in a given region during different periods of time [

32]. It seems to have a fundamental meaning in the case of the Vistula delta landscape, analysed herein, as it has been created by different groups of settlers living in Żuławy Wiślane for many decades. Taking all the above-mentioned into consideration, the cultural landscape of the Vistula delta may be perceived as a traditional one, and objects of the post-Mennonite heritage constitute harmonic elements of it.

The Vistula delta Mennonites were a group of Dutch settlers, both Mennonites and Anabaptists, which settled in Żuławy Wiślane at the beginning of the 16th century. They were an extraordinary group of people, having different beliefs, traditions and languages, who left visible manifestations of 400 years of their presence, including the elements of architecture, art, religion and crafts. Such a rich and diversified cultural heritage may become a core of a regional tourism product based on all aspects of the Mennonites’ daily-life (tradition, rites, customs, folklore, cuisine, etc.). The tourism industry, especially the so-called community-based tourism [

33,

34,

35,

36], could contribute to further economic development of Żuławy Wiślane, which is mainly an agricultural region. What is more, establishing an appropriate policy on preserving the heritage of the Vistula delta Mennonites could also lead to social development of the local community, shaping both the respect of their own as well as other cultures, which is essential to a proper course of globalisation processes [

37]. Nowadays, this seems to be a right response to threats imposed by an observed rise in manifestations of nationalisms in Europe. In this case, community-based tourism may not only stimulate the economy, but also social awareness.

Moreover, the creation of a regional tourism product may result in restoring many neglected objects (e.g., a church in Jezioro or Pordenowo cemetery,

Figure 1). However, establishing a fully-developed regional tourism product cannot be done without the active participation of local communities, as a positive attitude towards tourists is essential when creating tourism products, and it significantly affects their authenticity [

38,

39].

The main objective of this paper is to analyse how contemporary residents of the Vistula delta region perceive the cultural heritage of the Mennonites, which is so valuable that it cannot be simply ignored or destroyed. The Vistula delta is a unique region with the historical heritage left by people representing totally different religions, values and ways of life, as well as, what is extremely important, the people who are no longer present in the region and who, thus, cannot be advocates of their legacy. The work presented herein contributes to a better understanding of how rather closed rural communities living in a relatively culturally homogenous country perceive, comprehend and use the multicultural heritage and landscape of that country.

The paper is organized into five sections: (1) Introduction; (2) Research methods; (3) Multicultural landscape of the Vistula delta region, providing historical background of the research area; (4) Cultural heritage of the Vistula delta Mennonites in the eyes of current residents of the region, presenting the results of the survey research; (5) Discussion, highlighting the most important contexts of the study.

2. Research Methods

The analysis presented herein covers original data gathered during the fieldwork done in the period of 2017–2018 under the NCN Miniatura I project entitled “Perception and usage of cultural heritage of the Vistula delta Mennonites” (project ID: 2017/01/X/HS2/00137). For the purpose of this project, a survey instrument was implemented.

Survey research is widely practised in all of the social sciences and in most related professional disciplines such as human geography. It is, as defined by Check & Schutt, “the collection of information from a sample of individuals through their responses to questions” [

40] (p. 160). This type of research allows for implementing a wide range of methods to recruit respondents, collect data (both qualitative and quantitative) and interpret the results. Kraemer [

41] determined three distinguishing features of survey research: (1) it is used to quantitatively describe specific aspects of a given population; (2) the data required for survey research are subjective; (3) survey research uses a selected portion of the population from which the findings can be generalised back to the population.

Despite its disadvantages, which have been commented on since its implementation (e.g., [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]), when properly designed it still remains a versatile scientific tool for gathering data. It is especially useful when gathering information regarding people’s opinions and perception of things, including issues related to tourism, e.g., [

47]. The anonymity of surveys makes them even more useful when studying controversial or delicate matters, as in the case presented herein.

For the purpose of this study, a survey consisting of thirteen questions was created. Question 1 was of introductory character and the respondents were asked if they were aware of the fact that the Dutch migrants, called the Vistula delta Mennonites, used to live and work in the Vistula delta region (“Q1. Do you know that some Dutch settlers, called the Mennonites, used to live in Żuławy Wiślane in the past?”). If the answer was positive, the respondents were also asked to specify when and from what sources (people, media, etc.) they had obtained such knowledge. The second part of this question was of open-ended type and there was also a remark that they do not need to provide the exact date (a statement such as “in childhood” or “while studying at secondary school” was enough). Question 2 (“Q2. Would you like to learn more about the Vistula delta Mennonites history and customs?”) was a closed-ended one with three possible answers: (1) “yes,” (2) “no,” (3) “I don’t know.” It was aimed at finding out whether the respondents were interested in the history and customs of the Vistula delta Mennonites. Questions 3 and 4 were open-ended ones, closely related, as they both referred to objects being landmarks of the neighbourhood (“Q3. Which building, object or place do you consider the landmark of your village/town?”; “Q4. How often do you visit this place?”). The respondents were asked to indicate an object or objects which they perceive to be landmarks and how often they visit these places, e.g., while walking the dog. These questions were designed to check if the respondents indicate some post-Mennonite objects, even though they may not be aware who had actually erected them. Questions 5, 6 and 7 directly addressed the Vistula delta Mennonites’ heritage (“Q5. Should the post-Mennonite cultural heritage (e.g., the windmills, arcade houses etc.) be given special conservation status?”; “Q6. Do you think the post-Mennonite objects in Żuławy Wiślane could be interesting for tourists?”; “Q7. Should the local authorities invest public money in development of a tourism product based on the post-Mennonite cultural heritage?”). Before responding to these questions, the respondents were provided some additional information specifying which objects in their village or town had been built by the Mennonites. Question 5 asked whether the post-Mennonite objects should receive special conservation-based protection and offered (1) “yes,” (2) “no” and (3) “I do not care what will happen to them” as responses. In order to answer Question 6, the respondents had to state if the post-Mennonite objects are interesting enough to become tourist attractions. As for this question, there were also three possible answers: (1) “yes,” (2) “no” and (3) “yes, but they should be renovated first.” As for Question 7, about investing public money in the development of tourism products based on the Vistula delta Mennonites’ heritage, three closed- and one open-ended responses were provided: (1) “yes, it is an opportunity for the region and its inhabitants,” (2) “yes, but the amount of money should be limited,” (3) “no, there are other urgent expenditures” and (4) “other opinion: …”. Question 8 was the last directly related to the topic of the project and it was divided into two parts, yet the second part was planned to be answered only by those respondents who replied “yes” to the first one. At first, the respondents were asked whether they would be willing to provide some kind of services to potential tourists visiting their neighbourhood (“Q8. Would you like to provide services to tourists if your village/town became a tourist destination?”). When their answer was positive, they were asked to specify what kind of services they would be, choosing from the following options: (1) accommodation, (2) catering and food services, (3) agrotourism, (4) guided trips, (5) transport services, (6) selling agricultural raw materials, (7) selling handicraft products and souvenirs or (8) other services entered by the respondents themselves. In addition, the respondents were asked five standard demographic-type questions concerning their gender, age, name of a village/town they live in, length of residence and education level.

The survey was carried on using the Pen-and-Paper Personal Interview (PAPI) method during the period of 2017–2018. Although it was not originally planned, while interviewing the respondents some additional comments and remarks were recorded, e.g., the respondents mentioned several ongoing bottom-up initiatives aimed at promoting and preserving the post-Mennonite heritage, which will be mentioned in

Section 5: Discussion.

The overall sample size was 369 respondents. The Vistula delta region is a rural area with scattered settlements and small communities, which made the research challenging at the very beginning. Thus, in order to reach the first respondents, the author contacted representatives of the local authorities, i.e., villages’/towns’ mayors, and then the snowball method was used. The respondents were only adult (18 or more) permanent residents of the region and only one person per household could take part in the research, as in many cases the whole family was observing the interview with the first family member and commenting on the questions. As a result, the next interviewed people usually gave exactly the same answers. Those questionnaires were not included into the analysis. The data gathered have been analysed using statistical procedures, both descriptive and inferential.

The research area covered the Vistula delta region called, in Polish, Żuławy Wiślane or Żuławy in short. It is a region in northern Poland located in the Vistula river delta. Żuławy is a plain stretching longitudinally between the Vistual Spit and the Nogat river estuary to the Vistula and latitudinally between the Kashubian Lake District and the Elbląg Upland. The region covers an area of 175 thousand ha, including 45 thousand of depression areas with the lowest point in Raczki Elbląskie (−1.8 m below the sea level). Two main rivers flowing through Żuławy Wislane—the Vistula and Nogat—divide the region internally into: Żuławy Gdańskie, Wielkie Żuławy Malborskie, Małe Żuławy Malborskie and Żuławy Elbląskie (

Figure 2).

However, this division is conventional, as the region has been divided differently over time and there are historical maps and publications providing other divisions. Nonetheless, the division presented herein is helpful when describing settlement systems and the history of settlement.

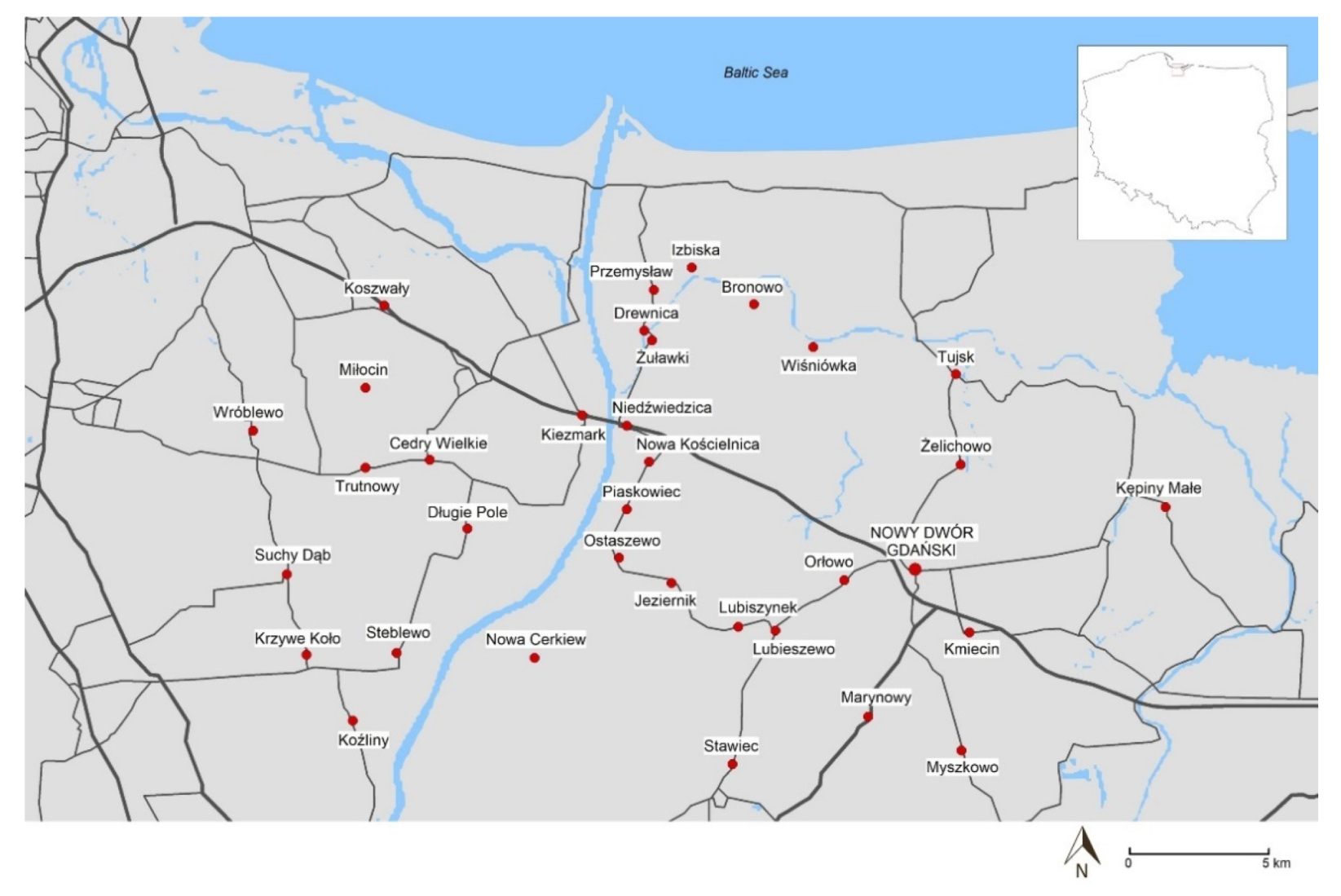

The research was carried out in the settlement units where the post-Mennonite objects are located (

Figure 3): 34 villages and 1 town—Nowy Dwór Gdański, where the only existing museum dedicated to the post-Mennonite heritage is located.

All tangible and intangible elements of the Vistula Mennonites cultural heritage that the past has conceded to the local communities create a unique landscape shaped by tightly connected anthropogenic and natural factors. This heritage is a keystone of local identity which plays a significant role in politics, economic development, society and world view [

48]. In order to understand how extraordinary the landscape of Żuławy is, when compared to the rest of Poland, it is necessary to look into its rich history and analyse all the factors that have shaped it through the years.

3. Multicultural Landscape of the Vistula Delta

Although natural forces shaping the landscape of the Vistula delta region are not directly addressed in this study, it is worth bearing in mind the fact that they used to prevail the anthropogenic ones in the past—numerous floods undermining human efforts reminded people of the great power of nature. According to Friedrich Ratzel and the concept of geographical determinism, those factors determine the conditions of settlement and civilization development. They may ease or hamper economic development or even make it impossible [

49,

50]. Taking the main subject of this article under consideration, the natural factors shaping the landscape of Żuławy Wiślane are not to be elaborated in great detail, although they have affected human efforts to transform the delta into an arable and liveable land. They were also a unifying factor, making people work together in order to survive; therefore, they exert a great influence on the people’s beliefs, values and symbols that can be visible in the landscape.

Historical, political, socio-economic, cultural and civilizational factors are among the anthropogenic ones that strongly influence landscapes [

4,

50]. They are especially meaningful in the case of the Vistula delta, as there are not many regions with such a complex and multilayered history in Poland.

Although the first traces of settlement in Żuławy Wiślane date back to the 2nd century BC, the period of the most intense development and prosperity started in 1308–1309, when the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order moved from Venice to Malbork. At that time, most new settlement units emerged mainly in Żuławy Malborskie in the southern part of Żuławy Gdańskie (

Figure 2). The next stage of settlement development started in 1466 when the Order lost in the Thirteen Years’ War and Żuławy Wiślane became Polish. Then, in the 16th century, Dutch settlers arrived in the region and settled in areas that had not been meliorated before. They were representatives of the Anabaptist movement which started in Switzerland during the time of the Reformation. The movement rapidly gained popularity in Europe, unlike their ideas, which were opposed to the traditional relationship between church and state. As a consequence, the new believers were persecuted, which led to a mass migration of the Anabaptists. In Poland, Mennonite congregations found business opportunities, land and religious tolerance. In Żuławy Wiślane, they settled near Gdańsk (Żuławy Gdańskie) and in Żuławy Malborskie and Żuławy Elbląskie [

48] (

Figure 2). As a result of their hard work and hydrotechnical skills, the region became one of the most fertile lands in the country. However, their situation dramatically changed after the Partitions of Poland (1771–1795), when Żuławy Wiślane became a part of East Prussia. As Mennonites refused to carry and use any weapons, they came into conflict with the new ruler—Friedrich Wilhelm II. In consequence, some of the Vistula delta Mennonites moved to Ukraine and settled there. During the Interwar Period (1918–1939), Żuławy Gdańskie and Żuławy Malborskie were part of the Free City of Danzig, yet Żuławy Malborskie was still part of East Prussia. At the end of World War II, in March 1945, the retreating German army destroyed the melioration system and floods turned the whole region into swamps and wetlands. It took three years to rebuild the irrigation canals. Right after the war, Żuławy was inhabited by a new group of settlers—the returnees from the Soviet Union and central Poland. They settled in randomly chosen villages and settlements. Then, when Poland turned communist, the new large-scale agriculture introduced sweeping changes into the landscape of Żuławy [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. When Poland became a democratic country, the region had to face another transformation. Nowadays, it seems that this multicultural history and heritage of the Vistula delta region is slowly coming to be perceived as an asset by its contemporary inhabitants.

Cultural factors are manifestations of gradual development of societies—they include: architecture, scientific and technical development, identity and other elements of an intangible nature, e.g., language, beliefs, traditions, religion, etc., [

50]. Each of the above-mentioned historical periods left some heritage that can be still visible in the landscape of Żuławy Wiślane. However, the most extraordinary elements of the Vistula delta cultural heritage are those created during the time period when the Mennonites lived there, i.e., from the second half of the 16th century to 1945, when those who had not moved to Ukraine were killed by the Red Army soldiers.

Spiritual culture of the Mennonites is tightly linked to their religion. They are Christian groups belonging to the church communities of Anabaptist denominations that represent a radical version of Protestantism. The church places a strong emphasis on a Christ-centred life and service to others as well as a repudiation of infant baptism and capital punishment. Mennonites were prohibited from holding public office and taking any oaths. The church has long held a belief in pacifism and the Bible as the only authority on belief and human life. Most Mennonites were iconoclasts and did not allow anybody to photograph them [

30]. As they did not allow strangers to take part in their ceremonies, there is virtually no iconographic material related to their spiritual culture. However, objects documenting the spiritual culture of the Mennonites living in Żuławy Wiślane can be found in the museum Żuławyski Park Historyczny in Nowy Dwor Gdański.

The unusual mosaic of elements representing material culture that create the landscape of Żuławy Wiślane is a result of complex settlement processes with visible medieval, gothic, Teutonic, Mennonite and other influences. The most characteristic and recognisable objects of material culture in Żuławy Wiślane include numerous sacral objects (churches, cemeteries), arcade houses, windmills, hydrotechnical buildings and the magnificent Castle of the Teutonic Order in Malbork. Mennonite cemeteries in Stogi, Stawiec, Szaleniec and Markusy are among the most valuable objects as well as churches (in Wróblewo, Nowy Staw, Lichnowy and Jezioro (

Figure 1a) and arcade houses such as those in Miłocin and Trutnowy (

Figure 4b). Other landmarks of the region are windmills in Drewnica and Palczewo (

Figure 4a) and Gdansk Head Lock.

One of the most extraordinary elements of cultural heritage of Żuławy Wiślane is in Stobbes Machandel. It is a juniper vodka that was produced by a Mennonite family, Stobbe, from 1776 to 1945 [

48]. Taking the current popularity of food tourism under consideration, Stobbes Machandel could become a vital part of the Vistula delta tourism product.

The group of socio-economic factors that exert direct influence on landscape includes settlement systems, forms of land and material goods ownership, as well as occupational and social structures. Here, the most characteristic elements of the Żuławy settlement landscape are the so-called “terpy.” They are natural or human-made hills on which houses and other buildings were situated. They are also proof of how people tried to grapple with the element water and how the natural features determined their everyday lives. Moreover, numerous floods forced people to adapt the architecture of their houses to the environmental conditions—the famous arcades were built to protect the crops. Another interesting and distinctive feature of the region is the field layout which owes its uniqueness to melioration ditches surrounding each field, making it easy to distinguish between single farmland areas.

When it comes to occupational and social structure, Żuławy Wiślane has always been inhabited by farmers and fishermen. Mennonites were definitely the group which had the most visible impact on the landscape. Because of their diligence and exceptional knowledge of land drainage, they became a wealthy and influential group. Their impressive arcade houses and windmills are still landmarks of the region.

The last group of factors shaping the landscape of Żuławy Wiślane is the civilisational ones which can be defined as intellectual and biological potential societies, accessibility to technological developments and material goods [

50]. Hydrotechnical objects—water watch points, pumping stations, locks, weirs, culverts, storm gates and drawbridges, e.g., in Kiezmark, Różany (

Figure 5), Osłonka and Rybina, are structures which have had tremendous influence on the present shape of the cultural landscape.

All the above-mentioned groups of factors shaping the landscape of Żuławy Wiślane, both natural and anthropogenic, are interconnected and have created a multicultural landscape which is unique and should be preserved. The diversity of structures observed in the landscape of the Vistula delta is a visible record of the long-lasting fight between the people and the element water. This apparently monotonous plain is a region full of cultural diversity—and this diversity is its valuable heritage and identity.

4. Cultural Heritage of the Vistula Delta Mennonites in the Eyes of Current Residents of the Region

The way that people currently living in the Vistula delta region perceive its cultural landscape was the main subject of the survey research, the results of which are presented herein. The total number of respondents who took part in the research was 369, including 205 women (55%) and 164 men (45%). The largest group of participants was between 41 and 60 years old (36%). The remaining age groups were (in descending order): 26–40 (28.7%), over 60 (21.4%) and 18–25 (13.3%). A vast majority of the respondents declared graduating from secondary or vocational school (70.7%). People with tertiary education comprised 14.4% of the respondents and 14.5% of all participants received elementary education. As has already been mentioned, the research was carried out in 19 selected settlement units where objects representing the Vistula delta Mennonites cultural heritage are located. The largest number of surveys were collected in the following villages and towns: Marynowy, Nowy Dwór Gdański, Nowy Staw, Ostaszewo, Lubieszewo, Orłowo, Cedry Wielkie, Suchy Dąb and Krzywe Koło (

Figure 3).

While looking into perception and the level of identification with a given region, it is important to gain information on how long the respondents have lived there. It seems logical to assume that the longer people live somewhere, the more they identify themselves with this place, perceiving it to be their homeland. In the case of the respondents from Żuławy Wiślane, 33% of them have lived there since they were born; 26.1% have lived in the region for more than 30 years and only 8.9%—for less than 10 years. Therefore, it may be stated that the residents of the Vistula delta region constitute a well-established community, which is of great importance, considering sustainable development of tourism and creation of the so-called hospitable space being an inseparable element of a community-based tourism product [

56,

57,

58].

According to Medlik and Middleton [

59], a fully-developed tourism product should consist of five elements which are: involvement, freedom of choice, the above-mentioned hospitality, service and a physical plant that is the core of the product. If local communities are planned to participate in a product development process, the core should be recognised by them. In the case presented herein, the post-Mennonite cultural heritage may be considered the physical plant of a regional tourism product of Żuławy Wiślane.

In order to assess the level of recognition and general knowledge of the Vistula delta Mennonites, the respondents were first asked whether they knew that such a group of settlers used to live in the region. Of those respondents, 71.8% confirmed that they were aware of this fact, while the rest admitted that they had not heard about it before. This group of respondents comprised mainly people having secondary/vocational (74.0%) or primary education (21.2%). Only 1 in 10 respondents with tertiary-level education was not aware that the Mennonites used to be residents of the region. The ones who had already had some knowledge of this matter were also asked how they had gained it (

Figure 6). More than a half of them (66.8%) claimed that they had been told about it by members of their families (47.2%) or by neighbours, acquaintances or other people living in the region (19.6%). One person admitted that her great-grandparents were Mennonites. However, a point of concern is that only 32 respondents (12.1%) named school as a place where they had learned about the past of the region and its former inhabitants. It seems that the regional education should be popularised in order to spread the knowledge and awareness that cultural diversity is a valuable asset that may useful for the future generations. Other sources of information that were mentioned by the respondents included Internet, books, TV and newspapers (16.2%).

When considering the development of regional identity, it is also important when a given person is taught about the past and cultural heritage of his/her homeland. Awareness and respect for cultural heritage left by other groups of people should be grounded from an early age. In the case presented herein, almost half of the 265 respondents who declared they had knowledge of the Vistula delta Mennonites stated that they acquired it in their childhood. At the same time, more than 50% of them were not interested in learning more on this subject. However, in the group composed of people who declared not having any knowledge of the Vistula delta Mennonites, almost 80% did not show any interest in gaining such knowledge. Generally, no matter the knowledge or its lack, 41.5% of all the respondents were willing to gain some more information on the culture, religion, history and heritage of the Mennonites who used to live in Żuławy Wiślane. Undoubtedly, a broad information campaign on the history of the region and its extraordinary heritage (i.e., cultural events, talks for children, etc.) may arouse interest among the residents. Moreover, it seems that the more educated the respondents, the more interesting the Mennonites are for them, i.e., 64.2% of the respondents with tertiary education and only 32.7% of those who graduated from primary schools declared a willingness to gain some more knowledge of the subject.

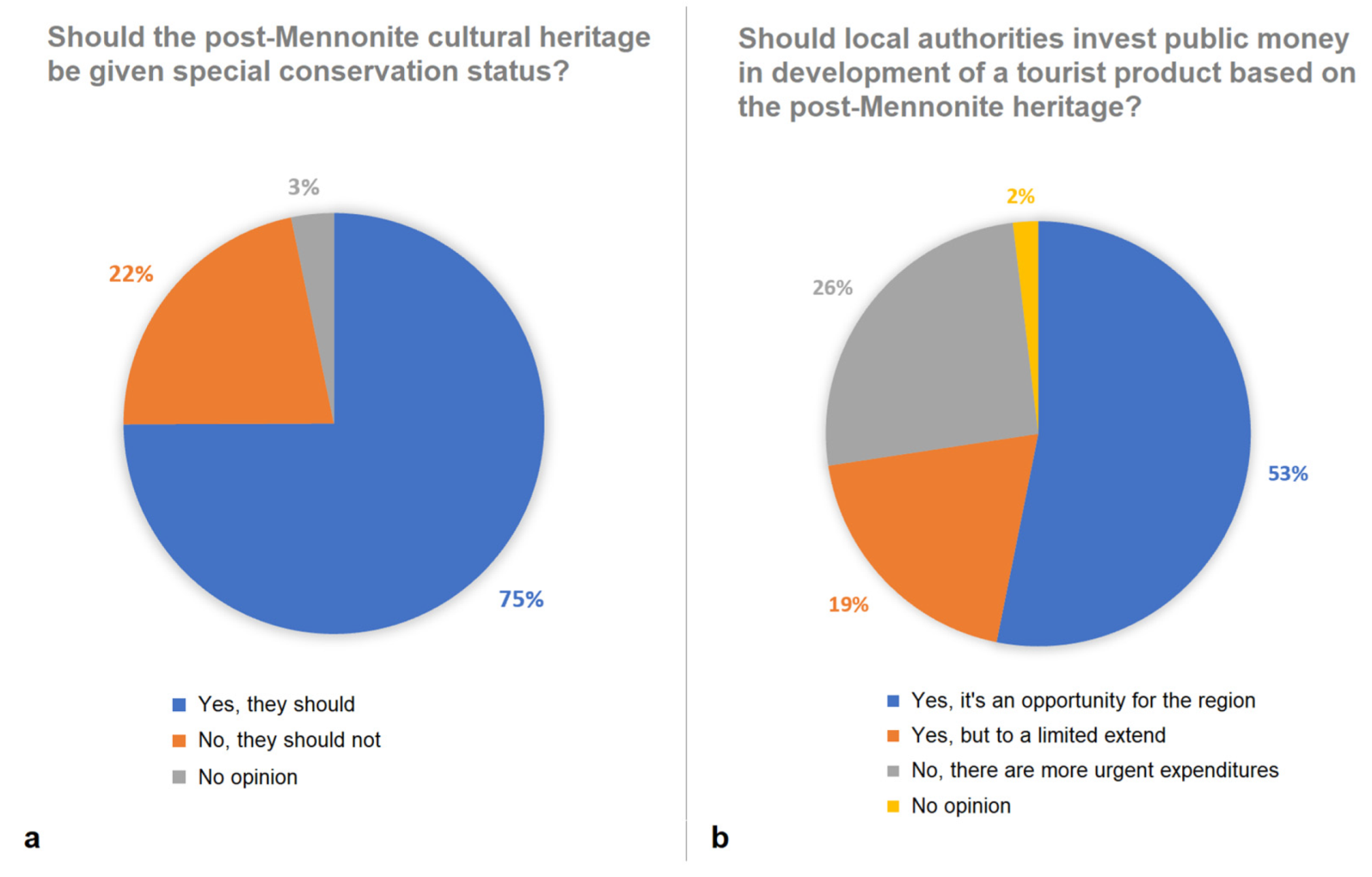

As for the respondents’ attitudes toward the objects representing material culture of the Vistula delta Mennonites, almost 75% of them agreed that those objects (cemeteries, arcade houses, churches, windmills, etc.) should be placed under protection and preserved (

Figure 7a). Considering the respondents’ age and education level, the analysis has shown, again, that, the more they are educated, the more they value the post-Mennonite heritage, no matter their age.

When asked about tourist potential of the post-Mennonite cultural heritage, a vast majority of the respondents (85.4%) stated that it may be perceived as a tourist attraction, yet most of the objects should be renovated. The respondents are aware of the poor condition of numerous objects, especially the cemeteries. However, there are also examples of the post-Mennonite objects owned by private individuals that have already been turned into places providing tourist services, e.g., an arcade house in Marynowy which has been turned into a guest house or an arcade house in Cyganek where a restaurant (named “Small Dutchman”) serving local cuisine has been opened. Such bottom-up initiatives can be considered a starting point for the development of a community-based tourism product, and their owners may become local leaders. According to Abas and Halim [

60], a lack of leadership is one of the limitations that leads to barriers for the local community to become involved in tourism activities. On the other hand, capable and committed local leaders are required to ensure local community participation and support to all kinds of tourism activities [

61].

More than 52% of the respondents agreed that the local authorities should invest in development of tourism products based on the Vistula delta Mennonites cultural heritage. Another 25.5% stated that such projects are important, yet their budget should be limited. Further, 19.2% of the respondents were strongly against spending public money on tourism, being convinced that there were more urgent expenditures in the region (

Figure 7b). Generally, the older the respondents, the more of them are for spending public money on tourism development, i.e., almost 60% of the respondents who are 60 or older and only about 40% of the respondents between 19 and 25 years old perceived investing in the development of tourism as a worthwhile opportunity.

Yet, despite the fact that the respondents generally perceived the Mennonite heritage as attractive, only 28.2% of them declared willingness to enter the tourist industry if it was possible. This group of 104 respondents consists mainly of relatively young people in the productive age (72.3% between 19 and 40), holding secondary-level education (72.1%). What is interesting, the majority of them are women (61.5%), and such a result is in line with the UNWTO finding that, in most regions of the world, women make up the majority of the tourism workforce. At the same time, women tend to be concentrated in the lowest paid jobs in tourism and they perform a large amount of unpaid work in family tourism businesses [

62]. Thus, when planning a regional community-based tourism product of Żuławy Wiślane, the UNWTO recommendations to bring gender issues to the forefront of the tourism sector and promote women’s empowerment should be kept in mind.

The respondents were also asked what kind of products they could offer or what kind of services they could provide the potential tourists with. Accommodation services, agrotourism and catering and food services were the three most frequently mentioned options (approximately 30% of all indications). Selling handicraft products and souvenirs (16 indications), guided trips (8), agricultural raw materials (7) and transport services (including waterway transport) (7) were also listed by some of the respondents. Such a wide array of potential elements of a tourism product listed by the locals, such as a rich cultural heritage and the proximity of the Vistula Spit sandy beaches, makes it possible to state that the Vistula delta region (Żuławy Wiślane) has sufficient potential to develop a community-based tourism product [

48,

53].

Having in mind the fact that almost one third of the respondents declared their willingness to participate in the tourist industry, and that there is a relatively large group of undecided respondents (23.8%), who may enter the tourism sector after being motivated by the first successes, it may be possible to create the so-called hospitality space which is one of the key components of a successful tourism product [

63,

64,

65].

5. Discussion

The multiculturalism, rich history and social relations which have been shaping the landscape of the Vistula delta region are undoubtedly a valuable asset. This cultural heritage—when used properly—may contribute not only to the economic growth, but also to development of the local community that will respect the history and cultural heritage left by the others while preserving their own identity.

As the issues addressing contemporary use and perception of the post-Mennonite cultural heritage in the Vistula delta region have not been subject to intense research, and as there is scarce literature regarding this matter [

66,

67], the results of the study presented herein may be interpreted and discussed in the light of top-down and bottom-up initiatives taken in the region.

The analysis of 24 local development plans prepared by the local authorities on different levels (counties and municipalities) showed that, in 15 of them, the post-Mennonite cultural heritage is recognised as the strength in SWOT analyses and the authorities of 12 analysed sub-regions formulated strategic objectives for development, including protection, or exploiting the cultural heritage in general. However, those objectives are sweeping, for instance, “shaping identity of the city on the basis of its history” (Pruszcz Gdanski); “preserving landscape values” (Kolbudy); “tourist exploitation of cultural heritage” (Miłoradz); “promoting heritage and legacy left by the previous generation, both tangible and intangible” (Nowy Staw); “supporting initiatives aimed at preserving cultural heritage” (Nowy Dwór Gdański). What may be alarming is that, in many documents, cultural heritage is mentioned only in the context of exploiting it in order to develop the tourist industry. Obviously, tourism can contribute to the preservation of objects of historical values; however, it can also pose a threat to them [

48]. Considering the above-mentioned and the fact that more than 50% of the respondents agreed that the local authorities should spend some public money on the development of tourism products based on the Vistula delta Mennonites cultural heritage, and almost 75% of them stated that those objects should be placed under protection and preserved, it is not surprising that numerous bottom-up initiatives have been launched. According to the information provided by the respondents themselves, and some additional data derived from employees of the Żuławy Historical Park in Nowy Dwór Gdański, there are at least six NGOs and associations involved in promoting and preserving the cultural landscape of the Vistula delta region, e.g., the Association of Nowy Dwor Gdanski Enthusiasts (Klub Nowodworski), which manages the Żuławy Historical Park and organises some events promoting the region (e.g., “Żuławy. I like it!”; “Żuławy Initiative”; “International Meetings of Mennonites” and others); “We love Żuławy” Association (Stowarzyszenie “Kochamy Żuławy”) organising trips and other events promoting the region among the locals and tourists; Żuławy Association (Stowarzyszenie Żuławy); Local Action Group—Żuławy and the Spit (Lokalna Grupa Działania—Żuławy i Mierzeja) and Żuławy Local Action Group (Żuławska Lokalna Grupa Działania). Moreover, there are also private people, enthusiasts of the region, taking actions aimed at preserving local cultural heritage: Marek Opitz, Łukasz Kępski, Mariola Mika, Marzena Bernacka-Basek, Artur Wasielewski, Dariusz Juszczak, Jerzy Domino, Roman Klim and Wojciech Hryniewiecki-Fiedorowicz, just to name a few.

However, not only elements of material culture create landscapes—historical tradition is also of great importance. Maintaining specific models of behaviour and ways of co-existence with nature make the regional features last. The history of cultural environment in the Vistula delta region has been created by consecutive layers of highly differentiated stages of settlement. Yet, all the groups of settlers were dominated by the continuous fight with the element water. Nowadays, the historical tradition is almost forgotten, as there is no longer its basic driving force—a man who has a strong multi-generation bond with the region. According to B. Lipińska, the old, traditional and consolidated community and its memory does not exist in Żuławy Wiślane and there is no stronger force than the common effort of people who share the same objectives and interests. Such an effort can lead to the creation of harmonic landscapes even in large regions. Nowadays, there are no living descendants and natural successors of the old traditions that used to be cherished by the former communities living in the Vistula delta. This is a result of the displacement, emigration and extermination of the residents during and after World War II and in the earlier times. Thus, the cultural tradition of Żuławy Wislane has lost its social foundation and continuity [

53]. This may be the reason why so many post-Mennonite objects are currently unused and neglected. Such poor conditions of the post-Mennonite objects in the region may suggest hidden or unconscious indifference, fear or prejudice that should be investigated using more in-depth methods. Therefore, a new project proposal has been submitted this year to the National Science Centre in Poland entitled “Cultural heritage of Polish Mennonites: its perception and role in shaping local identity in the context of community-based tourism” and using the Community Reporting methodology that provide both friendly environment and opportunity to take individual cases into consideration [

68]. A lack of information concerning elements of culture that are perceived as unifying the community may be considered as a limitation of the study presented herein.

The case of the Vistula delta Mennonites and their cultural heritage provides a great opportunity to test the idea of adoption through utilisation. If the contemporary residents of the region recognise the post-Mennonite heritage as usable and profitable, they may, to some extent, consider it as their own and try to preserve it. Here, community-based tourism (e.g., [

69,

70,

71]) may provide some solutions and cooperation while creating a regional tourism product will create a “workbench” for developing local identity based on the rich and multicultural history of the region. Such an experiment, with the use of Community Reporting, has not been carried out in Poland yet.

Living in regions with rich history and cultural heritage seems to be an obvious privilege, as such values create vast development opportunities, including the development of the tourism industry. Tourism is perceived as a key economic development factor and a way towards local community wellbeing [

72]. However, the development of a successful tourism product involves close relations between tourists and local people, especially in rural areas [

64,

65,

66]. Therefore, recognition of the post-Mennonite heritage as a valuable asset is crucial for creating the so-called hospitality space which is of fundamental significance for proper and effective development of a tourist function in rural areas [

73,

74,

75]. In the case of the Vistula delta region, the majority of respondents perceive the post-Mennonite cultural heritage as valuable and potentially interesting for tourists. Moreover, one third of them declared that they would like to provide some tourist-related services if they had a chance. The number of bottom-up initiatives aimed at preservation and promotion of the Mennonite cultural heritage which are currently observed supports the statement that multiculturalism is slowly becoming part of the Vistula delta residents’ everyday life. It is also crucial for achieving sustainability goals, as the same principles and mechanisms of sustainable development can be applied for preserving both natural and cultural values—after all, they are all the heritage of the past, no matter if they have been made by nature or people.