1. Introduction

The real economy serving society needs financial institutions that direct resources towards activities that provide societal empowerment, economic resiliency, and environmental regeneration [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Financial institutions, mainly the banking sector, play a vital role in economic development and growth by ensuring financial intermediation. The banking sector is the most central part of the financial system in most economies and is, therefore, also the main important sector for the financial system’s stability [

5]. The financial soundness and resilience of the banking sector have significant impact on the stability of the financial system as a whole [

6]. After the global financial crisis, banks’ strategies to reduce the traditional model and focus on stability can be observed. The global financial crisis forced financial institutions to revise their activities and develop more resilient and sustainable business models. Many financial institutions have reassessed and adjusted their business strategies and models, including their balance sheet structure [

7]. In this regard, banking institutions, especially value-based banks, emerged with new models that uniquely positioned them to foster economic sustainability by offering more innovative and value-based financial services and products necessary to serve a broader spectrum of stakeholders [

8].

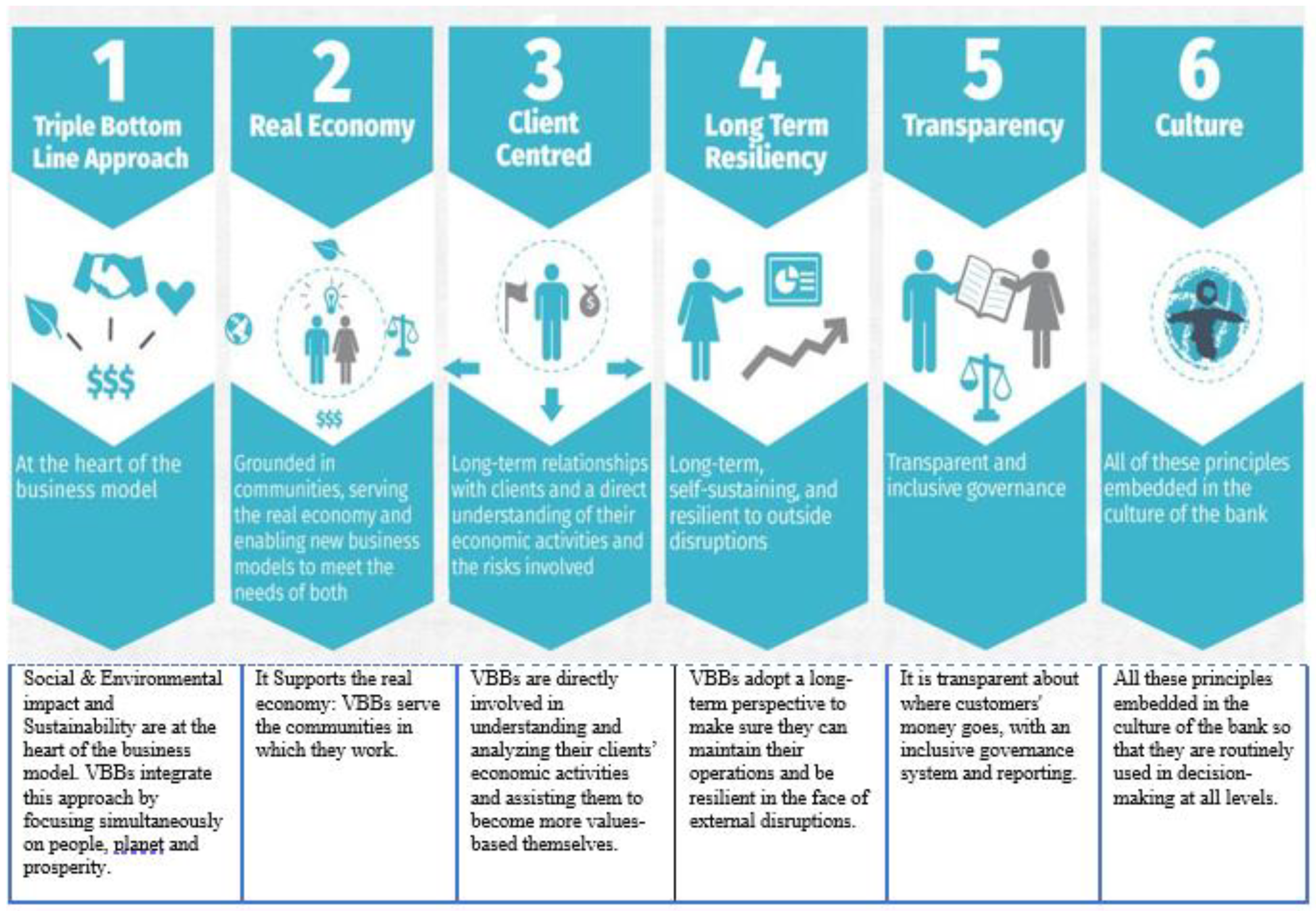

Different explanations are provided in the literature for the concept of value-based banking. Various researchers have provided overviews of different definitions and approaches [

9,

10,

11]; however, in general, value-based banking refers to a dynamic trend that shares common characteristics with other models, including community banking, ethical banking, and green banking, in addition to socially oriented banks such as cooperatives banks and credit unions [

9,

12,

13]. Value-based banks provide a similar range of services to traditional banks, including savings accounts, investment management, and venture capital funds. However, what makes them different from traditional banks is how they achieve this, how they manage and where they invest their customers’ money, and how they support the economy, society, and the environment [

14].

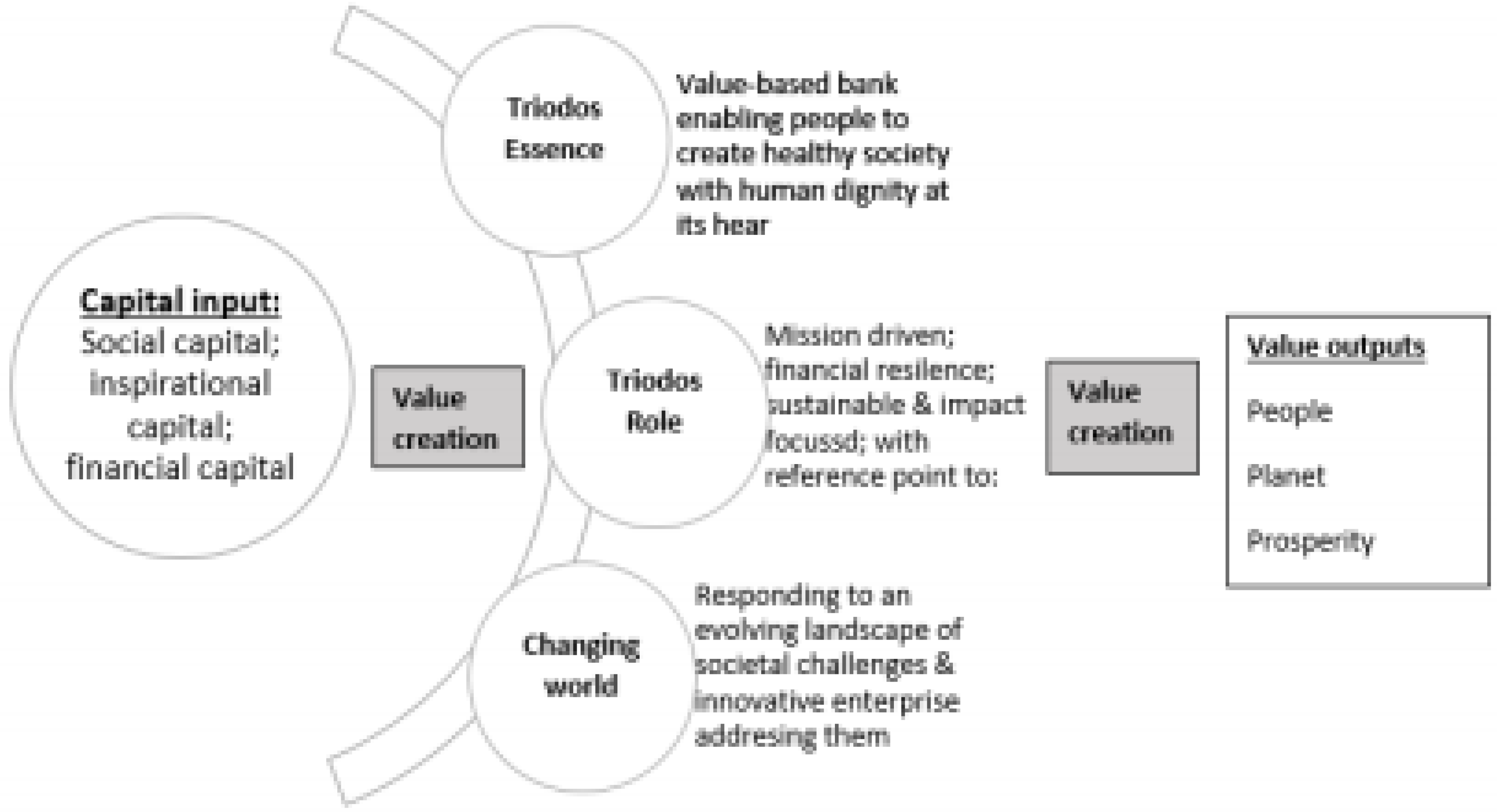

The ultimate goal of value-based banking is to attain stable economic, social, and environmental development through delivering banking services and investment products using a value-based strategy that is more than corporate social responsibility [

8]. Simultaneously, they provide sustainable and positive returns to their shareholders [

15,

16]. However, in value-based banking, profit maximization is not the ultimate goal of the banks; instead, the aim is sustaining and growing value in the real economy by supporting society [

17]. The underlying principle of value-based strategies is the ‘People before Profit’ principle [

14]. In contrast to traditional banks, VBBs generate profits through investing in ethical projects that have a social or ecological impact and through channeling funds to high-impact industries that promote equality, employability, environmental sustainability, cooperation, commitment, and reinvestment [

18].

Value-based banks focus on entrepreneurs and SMEs seeking to develop a more inclusive and sustainable society through their social innovations [

8]. Their strategies bring economic justice to society and help direct resources toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

13]. Since their strategies focus on sustainability and committing to social and environmental responsibilities, they also reduce their vulnerability to risk [

19]. Many studies in the literature have established that considering the social and environmental aspects of a business helps firms to reduce their risk exposures [

20,

21,

22,

23].

The goals of value-based strategies align with Islamic finance’s theoretical aspirations and are seen as a natural progression for Islamic banking. Unlike mainstream banking, Islamic banking, which is guided by

Maqasid al-Shariah (the Objectives of Shariah), is rooted in creating a value-based economy and social justice [

24]. The Shariah guidelines encourage, and sometimes urge, Islamic banks to concentrate primarily on ethics and morals relevant to socio-economic values such as fairness, sharing, partnership, well-being, and justice based on economic value proposition [

25]. The initiative for value-based strategies, also known as value-based intermediation (VBI), in Islamic finance has emerged in recent years in Malaysia. The initiative aims to position Islamic banking as a prominent and leading agent of positive change in the global financial system [

26].

There is a convergence between Maqasid al-Shariah and the SDGs, as sustainability and inclusive development are focal points in both cases. The intended outcomes of Shariah are in line with the SDGs, which focus on enhancing society’s well-being. The purpose of value-based strategies is also to achieve overall development by ensuring financial inclusion and sustainable and inclusive growth [

27]. Value-based strategies are essential to achieving the intended outcomes of Shariah through practices, conduct, and offerings that generate positive and sustainable impacts on the economy, community, and environment, consistent with the shareholders’ sustainable returns and long-term interests [

26].

However, due to the existing gaps between theory and practice in Islamic banking, realizing the objectives of the

Shariah in current Islamic banking practice is not straightforward. An enabling environment to embed

Maqasid al-Shariah in the culture of Islamic banks needs to be created [

26]. Despite substantial growth in their assets and numbers, Islamic banks have been highly criticized due to their lack of innovation and social concern in their economic activities, which is one of the most significant elements of the

Maqasid al-Shariah [

28,

29]. Therefore, it is essential to develop a range of strategies to bridge the gap by incorporating

Maqasid al-Shariah into the activities of Islamic banks [

26]. Embedding Maqasid al-Shariah in the activities of Islamic banks will help to promote their sustainability and contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This will help the banks to realize socio-economic development objectives by introducing modern and welfare-oriented banking products [

30].

Realizing the existing gaps, the central bank of Malaysia collaborated with other stakeholders and proposed several strategies aimed at filling the gap and further strengthening the roles and impacts of Islamic financial institutions [

26]. The proposed strategies and guidelines are based on Shariah principles, which define the moral compass, underlying principles, and priorities of Islamic banks [

28]. The strategies guide Islamic banks to improve their current practices and position towards innovation. The VBI proposes a shift in the practical paradigm of Islamic financial institutions, while fostering their efficiency and growth by inventing new opportunities for more responsible and diversified business segments [

26,

31].

It is generally argued that Islamic banks are safer than conventional banks during financial crises. Studies indicated that the 2008 financial crisis not only affected conventional banks; it also challenged Islamic banks [

32]. However, Islamic banks had demonstrated significant resilience during the crisis period. There are many reasons given for their resiliency, including their product structure, relying on real economic activities, and avoiding toxic financial derivatives [

24,

33]. Similarly, value-based banks not only showed resilience throughout the recent global financial crisis, but also advocated for a safer and longer-term banking model, which would avoid the speculative investments that are at the root of most crises, and which are particularly destructive to businesses and enterprises with less financial resources [

34].

On the other hand, VBI brought many changes to Islamic banks. Although all Islamic banks are Shariah-compliant, banks adopting VBI differ from others as they have modified their business models and focused on value-based activities. VBIBs have made many changes in their investment focus, asset structure, and inclusiveness. They focus more on entrepreneurs and SMEs seeking to develop a more inclusive and sustainable society through their social innovations [

8,

26]. However, the role of VBI on the efficiency and resilience of Islamic banks has not been studied. Despite the enormous benefits of VBI to the economy, society, and the environment, it is not yet widespread and adopted by other banks outside Malaysia. The reasons for this range from policy constraints on implementation to uncertainty about its financial viability and contribution to banks’ resilience and efficiency. Hence, it is vital to explore the importance of adopting VBI in the banking business in terms of enhancing resilience and efficiency and earning sustainable returns for the adopting banks. To the best of our knowledge, there is a gap in the Islamic finance literature: empirical studies assessing the financial performance and resilience of value-based Islamic banks in comparison to mainstream value-based banks and traditional banks are lacking.

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the role of integrating value-based strategies into the activities of Islamic banks to enhance their efficiency and resiliency in the face of future economic crises. The study also attempted to assess the importance of value-based strategies to enhance the impact of Islamic banks on the real economy and socio-economic dimensions by concentrating resources on value-based activities that provide economic resiliency and enhance inclusive and sustainable economic growth. Furthermore, the study evaluated value-based Islamic banks and compared them to the mainstream value-based banks and GSIBs in terms of variables such as stability of earnings, capital strengths or capital adequacy, contribution to the real economy, growth in the balance sheet, profitability, and efficiency.

The contribution of this study is two-fold: The findings contribute to filling the existing gaps in the Islamic finance literature on assessing the resilience and efficiency of value-based Islamic banking. The findings also demonstrate the practices of value-based banks based on the experience of renowned impactful banks, which are members of GABV, and recommends lessons that Islamic banks should learn from these banks’ best practices related to designing value-based products, implementing, and monitoring. Thus, the findings might help practitioners, policymakers, bank board directors, and investors understand the stability and efficiency of value-based banking practices.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical framework, illustrating the concept and practice of value-based banking in the mainstream and Islamic finance system.

Section 3 explains the data and methodology used in the analysis. It presents the research design, data, data sources, and the samples.

Section 4 presents the results and draws a comparison with three banking strategies.

Section 5 presents the discussion, content analysis, and recommendations with policy implications.

Section 6 offers the conclusions, limitations and future research directions.

3. Materials and Methods

Assessing sustainability and resilience requires considering a broad spectrum of risk factors, and it is not expected that a single model will satisfactorily capture all factors. Instead, a suite of models may be required [

6]. However, this study aimed to assess the role of value-based strategies to enhance the stability, efficiency, and resilience of value-based Islamic banks (VBIBs) by considering the fundamental parameters that show the overall stability of the banking sector in simple terms. The rapid growth of VBIBs has been accompanied with claims about its relative resilience to financial crises as compared to VBBs and GSIBs. Using data from Malaysia, Bangladesh, and Indonesia where Value-based Islamic banks exist, we sought to show how VBIBs are efficient and resilient compared to the VBBs and world-leading GSIBs.

We compared VBIBs with the mainstream value-based banks (VBBs) and global systemically important banks (GSIBs) based on the selected parameters. In addition, we examined the asset and investment structure of the VBIBs to explore their contribution to the real economy, to enhancing the social dimension of banking, and to improving the well-being of society by promoting entrepreneurial activities, corporate social responsibility, and the banks’ welfare activities.

Accordingly, to achieve these objectives, the study applied both content and empirical analyses. Empirical analysis was used to assess the selected value-based Islamic banks’ capital adequacy, profitability, efficiency, and stability. We compare the three groups of banks based on financial parameters that predict the banks’ financial soundness and resilience such as asset qualities, capital adequacy, efficiency, and financial ratios, including ROE, ROA, non-performing loan rate, etc. Content analysis was applied to assess the social impact of the selected Islamic banks’ value-based banking practices.

3.1. Data and Sampling

The study was carried out mainly based on publicly available data collected from various secondary sources such as the annual reports of the selected banks and reports released by central banks, the GABV, and the BIS report. The dataset covers four years from December 2017 to December 2020. We limited the study period to this timeframe due to the unavailability of data as the VBI is a new concept in the Islamic banking sector and started in 2017. Therefore, the data were only collected from Islamic banks that were listed on a stock exchange and had been implementing VBI strategies in their banking activities.

The analysis was based on a sample of impact frontrunner banks that were members of the GABV and Islamic banks that apply VBI. The study’s sample included 10 value-based Islamic banks from Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Malaysia. The reason for choosing these countries was based on the availability of Islamic banks that implemented VBI. Malaysia is the founder of the concept and the others have one or more banks that have adopted VBI as well as the GABV’s value-based banking strategies. The sample size for the mainstream value-based banks (VBBs) and the global Systematically Important Banks (GSIBs) was based on the data available in the GABV database. Accordingly, the data for a total of 30 GSIBs and 52 value-based banks and banking cooperatives (VBBs) were extracted from the GABV database.

3.2. Variables and Econometric Models

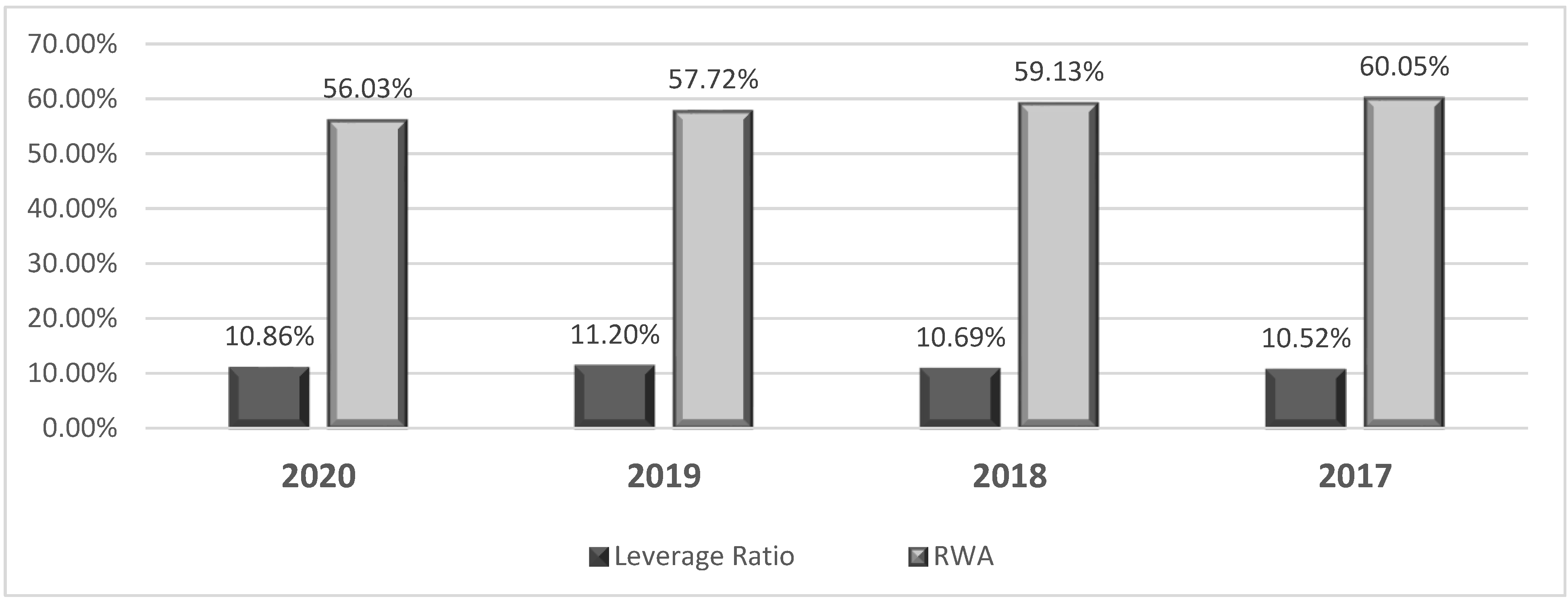

We used a time series analysis that covered the banks’ activities from 2017 to 2020. The 2020 fiscal year’s data enabled us to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the performance of value-based Islamic banks. The three groups of banks were compared based on various performance parameters, including quality of capital, profitability, efficiency, and leverage (Basel III) [

46]. As Basel I and II [

47] have placed special emphasis on the capital adequacy of banks as an indicator of the safety of banks, we used the Tier 1 (core capital) ratio, total CAR, RWA, and equity-to-total assets ratios as the indicators of the banks’ stability and resilience [

24,

48,

49]. Parashar and Venkatesh [

24] applied the combination of these variables and econometric models to compare the condition of Islamic banks with that of conventional banks during the global financial crisis. Accordingly, we used the same econometric models and parameters as used to assess the resilience of VBIBs to measure the conventional value-based banks.

Capital adequacy: The capital adequacy ratio (CAR) measures the amount of capital, based on the Basel III requirements, that banks should hold in relation to their total risk-weighted assets. It is the most important ratio for gauging the safety and soundness of a bank [

24,

49]. A comfortable CAR increases confidence in the safety and soundness of a bank, especially in times of crisis. The higher the CAR, the stronger the bank’s stability, and the lower the probability of failure, and vice versa [

6,

32,

50].

Notably, a bank’s risk weighted assets (RWA) are calculated by multiplying the exposure amount by the relevant risk weight for the type of loan or asset as per the Basel II and III standardized approach [

46,

47]. A bank repeats this calculation for all of its loans and assets and adds them together to calculate total credit risk-weighted assets.

Equity to total Assets Ratio: A high degree of shareholders’ equity used to finance the bank’s assets decreases the bank’s insolvency risk during times of crisis [

48].

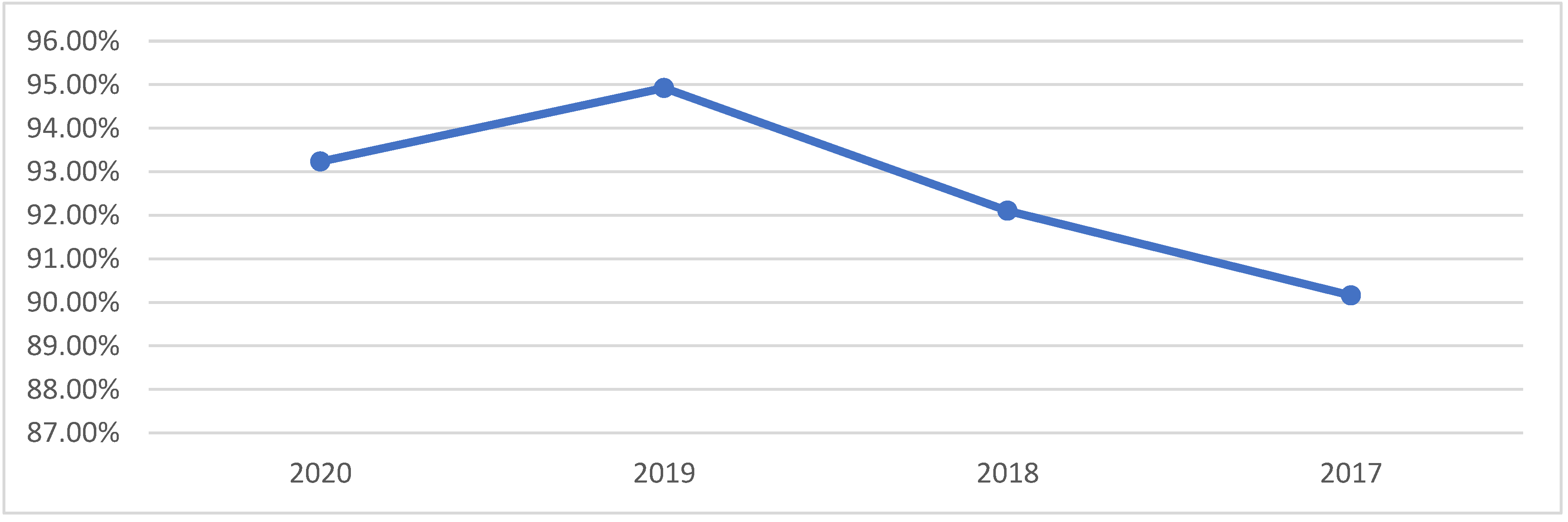

Non-Performing Assets (NPL/NPA): Management of non-performing assets is key to the stability and continued viability of the banking sector. The ratio shows the extent of deterioration of the quality of loans granted by the banks. The NPL ratio is calculated by dividing the non-performing assets to Loans and advances [

51].

In general, the lower the ratio, the higher the bank’s stability. The higher the ratio, the worse the quality of the assets, and, consequently, the higher the expected losses

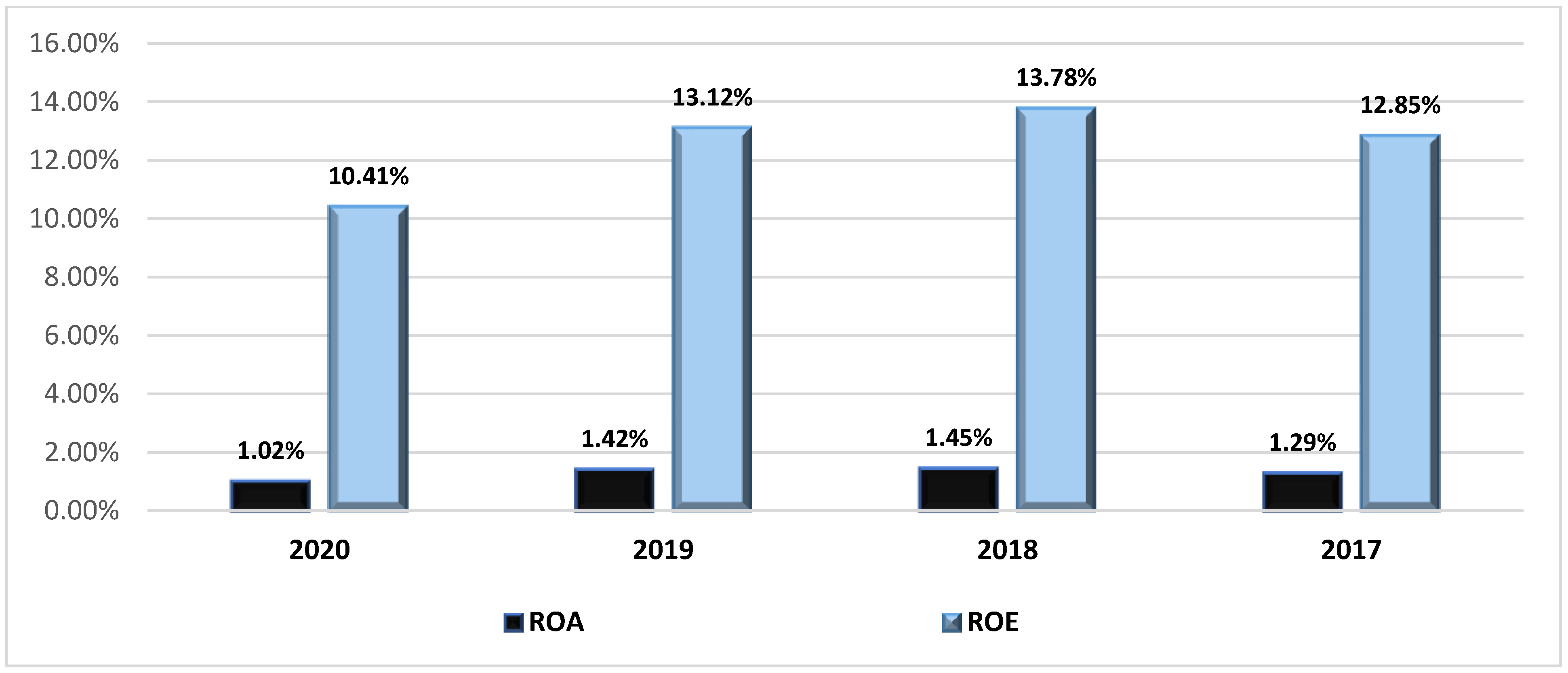

Profitability and efficiency: We used the two standard and commonly used measures of profitability ratios, return on average assets (ROA) and return on average shareholder equity (ROE), to assess the returns provided by VBIBs to their clients, investors, and society [

16,

52,

53]. The ROE ratio is an indicator of banks’ overall profitability as it relates banks’ net income to total capital. ROA is perhaps the most crucial single ratio in comparing banks’ efficiency and operational performance as it considers the returns generated from the assets financed by the bank [

24].

Return-on-Average Assets (ROA):

A high profitability suggests that banks are in a favorable position to increase their capital buffer in the immediate future, namely through retained earnings.

Cost-to-income ratio (CIR): The CR essentially belongs to the family of profitability ratios, and it provides a good overview of banks’ operating efficiency as it compares operating costs with operating income.

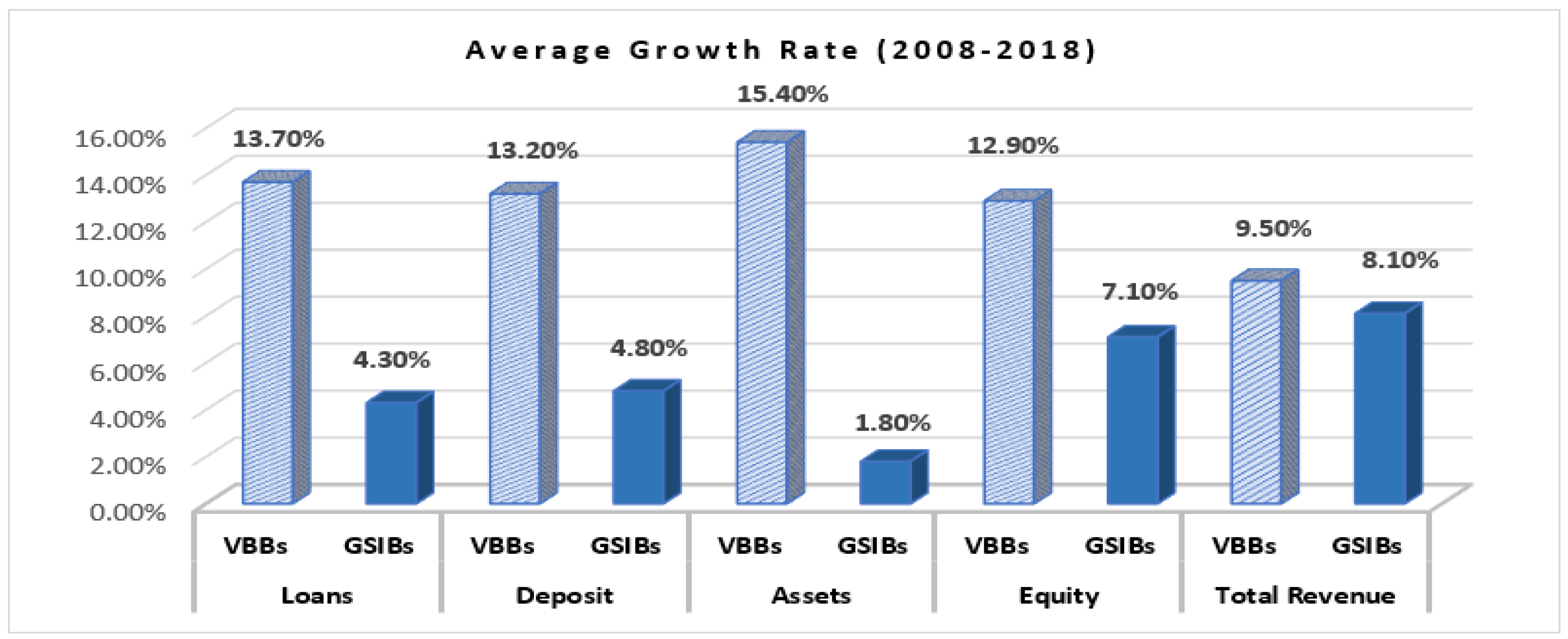

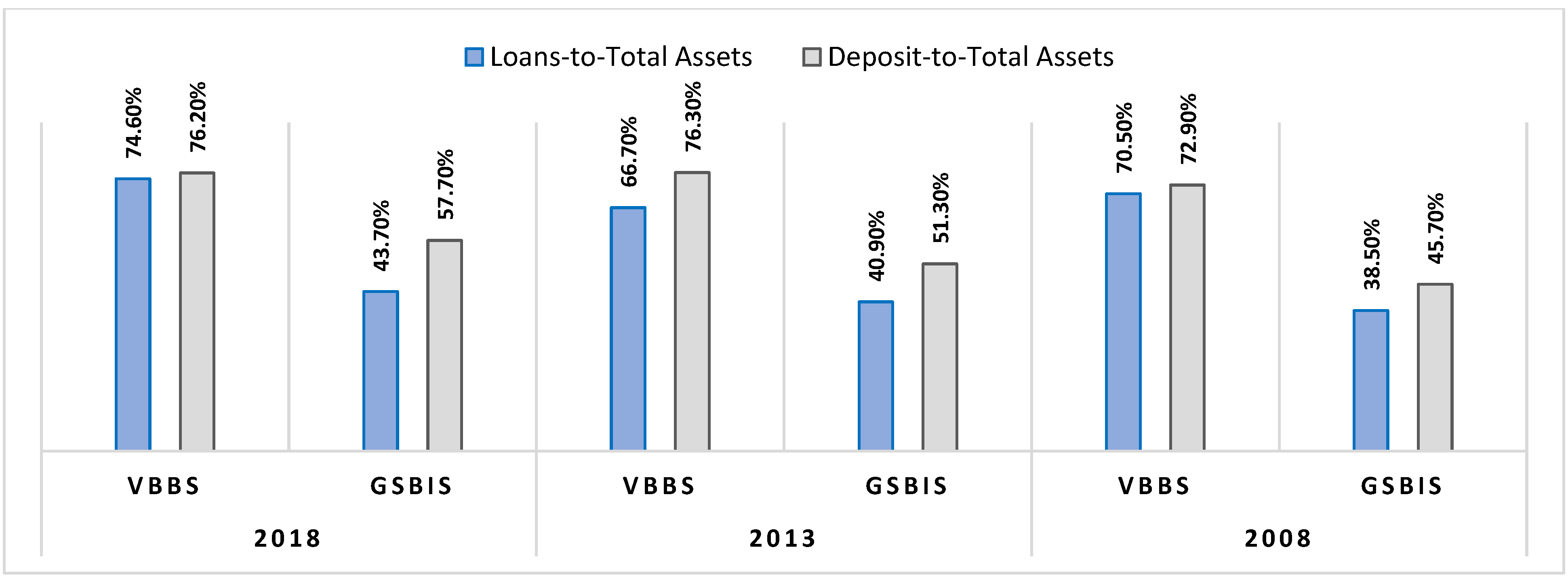

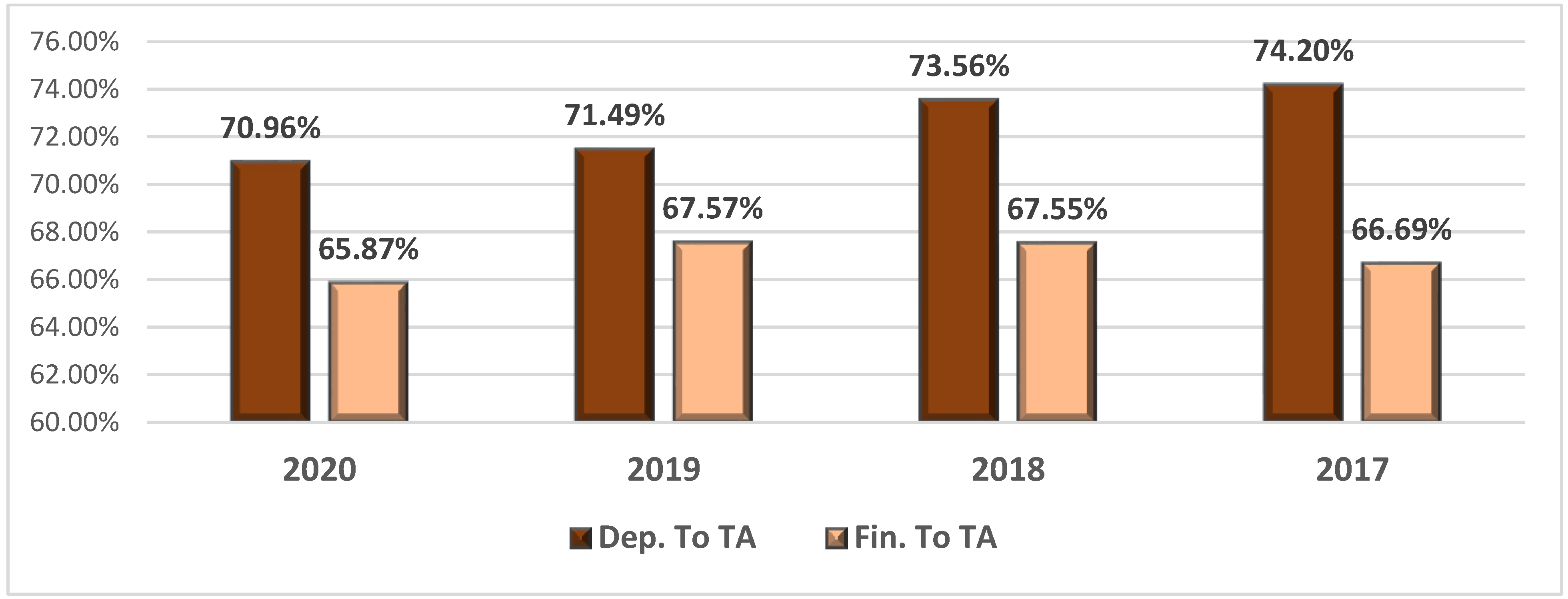

Structure Ratios: Structure ratios are the other important indicators of banks’ stability or resilience. They measure the level of various components of the assets by which banks finance the real economy [

8,

36]. The two most important parameters used in this case are: loans to total assets and deposits to total assets ratios [

52]. It is also important to know the growth a bank achieves in total assets, equity, financing, and deposits to expand its impact in society. Therefore, in this study, Islamic banks were compared with the VBBs and GSIBs based on the growth rates of their assets, equity, deposits, deposits, and total revenue.

5. Discussion

The empirical results showed that VBBs are more resilient and provide an immense contribution to the real economy, consistent with the shareholders’ sustainable returns and long-term interests. Our findings are in line with those of Schäfer and Utz [

56], who reported that VBBs exhibit significantly higher financial stability compared to GSIBs. The results should encourage Islamic banks to revise their strategies and learn from these banks’ best practices related to designing value-based products, implementing, and monitoring. The nature of Shariah-compliant financing products and the risk-sharing principle promotes bank stability and sustainability and inclusiveness in the economy. Since Islamic banks are supposed to finance underlying assets, their stability and sustainability originates from their activities. The ultimate goals of the GABV principles and strategies are in line with the intended outcomes of Shariah, which include generating a positive and sustainable impact on the economy, community, and environment. Therefore, the value-based banking strategy can be regarded as a crucial opportunity to leverage Islamic banking activities to attain sustainable banking.

Islamic banks focus on the social aspects of their activities and their positive impacts on society, the economy, and the environment. Since the guidelines promote needs-based banking and their strategies promote mass banking, banking facilitates innovative products to be available for many people. The value-based strategies and principles adopted by the GABV aim toward overall development by ensuring financial inclusion, sustainable and inclusive growth, and socio-economic development by introducing modern and welfare-oriented banking products.

Therefore, blending the GABV principles or VBI strategies with Islamic finance principles enables the realization of the Maqasid al-Shariah in Islamic banking. By realizing Maqasid al-Shariah, Islamic banks can play a supportive role in developing a sustainable economy. Their Shariah-compliant products can deliver holistic value to all stakeholders and provide long- and short-term solutions during a crisis. They enable banks to create value for all stakeholders and prioritize needs in financing as per the Islamic Shariah. Through their various special investment products and schemes, they can work to uplift people’s socio-economic status and address the special needs of particular groups.

The socio-economic dimension of value-based banks plays a significant role in finding sustainable solutions. Microfinance and other financial inclusion instruments play a significant role in changing the lives of millions of people worldwide. Most value-based banks and financial institutions are at the forefront of these innovations [

34]: they provide economically viable banking options centered on society’s needs, resulting in a more diverse financial ecosystem. The strategies also enable banks to create a strong link with entrepreneurs as they play a vital role in achieving the economic development and socio-economic well-being of society.

Reports and strategic papers released by the GABV and Bank Negara indicated that value-based business models help financial institutions to meet the real banking needs of enterprises and individuals in their communities. As suggested by Bank Negara, supporting entrepreneurs and community empowerment are two of the four essential pillars of the VBI. Thus, strategies enable value-based banks to facilitate entrepreneurial activities through financing, designing impact-based products to support entrepreneurs, providing advisory services and market structure, and creating a strong business network.

The content analysis of the VBIBs’ annual reports demonstrated that VBI enables the banks to maximize their value to all stakeholders through establishing needs-based banking. Since product development and special investment schemes should be based on the needs of clients or society, value-based strategies also enable Islamic banks to substitute greed-based banking by establishing needs-based banking [

57,

58], for example, by embedding the strategies to enable Islamic banks to work continuously with or to finance needs-driven social finances, including micro-finance, which works to uplift the well-being of the society. Moreover, the VBI strategies enable Islamic banks to create financial solutions that have a socio-economic impact on various communities. VBIs propose innovative products and localized solutions to support the most vulnerable and excluded groups for various reasons, including lack of finances. These activities, at the same time, create business opportunities for Islamic banks. We think that value-based strategies will help Islamic banks introduce welfare-oriented banking, ensuring equity and justice in all their activities.

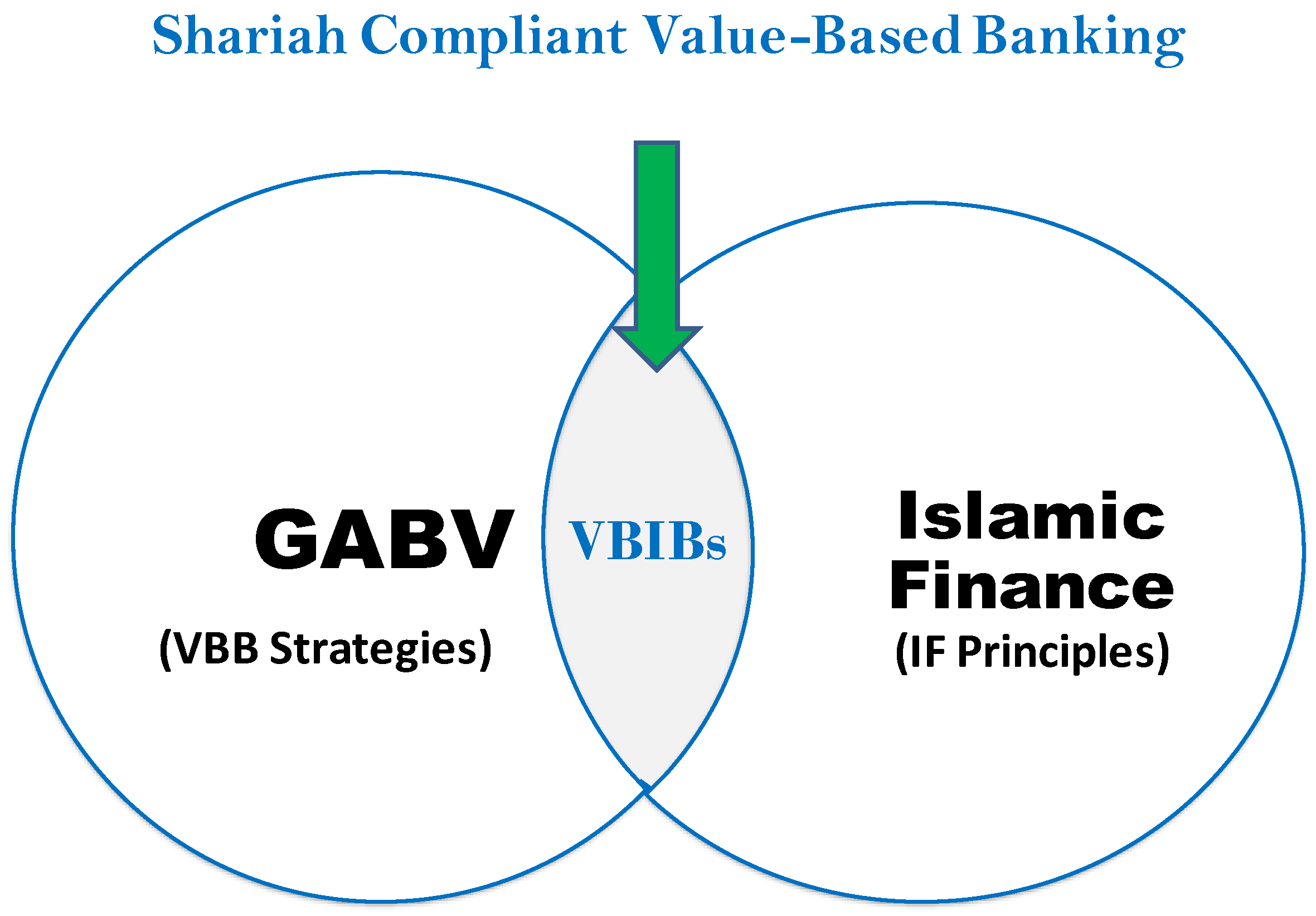

Furthermore, value-based banking has a comprehensive measurement system covering both financial and social indicators, increasing the balanced motivation to attain both short- and long-term goals. Accordingly, our study underlines the importance of convergence between value-based banking strategies and the Islamic finance principles to reshape the Islamic banking sector. It is vital to explore synergies between the GABV and Islamic finance principles to develop Shariah-compliant value-based strategies for Islamic banking institutions. This study proposes the formation of a Shariah-compliant value-based banking that will be guided by value-based strategies (

Figure 10). Developing new value-based strategies based on Islamic finance principles and the GABV guidelines is important to optimize the impacts and sustainability of the Islamic banking system. Banks and financial institutions operating based on the new principles and strategies will have the characteristics of the mainstream value-based banks while being Shariah-compliant. As value-based principles are aligned with

Shariah, integrating these core principles into the Islamic banking business operations is expected to significantly increase their positive impact on a broader range of stakeholders, and will improve the banks’ sustainability and stability, and the financial system’s ability to mitigate the impacts of future financial crises.

6. Conclusions

Islamic financial institutions can embrace value-based strategies while still meeting the expectations of governments, regulators, and the general public in their respective countries. However, value-based strategies implemented based on Islamic banks’ interests alone may not produce the intended results. To reshape the Islamic banking sector based on value-based strategies and make it more sustainable and resilient to future crises, collaborative efforts and the initiatives of various stakeholders, including Islamic financial institutions’ managers, board of directors, policymakers, fund managers, and market makers, are needed. The board of directors and management bodies of Islamic financial institutions need to show interest in implementing the recommendations set by initiators and policymakers.

Government interventions through different policies and incentives can accelerate the development and implementation of effective strategies that respond to the needs of society, the economy, and the environment. Regulators and policymakers should develop the necessary legal framework and implement policy measures to facilitate the development of value-based strategies and integrate those principles and strategies into Islamic financial institutions’ activities. It is essential to move from policy divide to policy coherence and convergence to create an environment that enables the implementation of value-based strategies and guidelines globally in Islamic financial institutions. Regulatory authorities have set a precedent by requiring financial institutions to formalize and implement sustainable banking principles.

We think that fundamental research should be conducted to assess the social impact of VBI in detail. The studies should address the possibility of convergence between the GABV’s principles and Islamic finance principles to develop more impactful Shariah-compliant value-based banking within the Islamic banking sector. Future research could use data envelopment analysis (DEA) [

59,

60] and other models to analyze differences regarding the social efficiency of Islamic banks and mainstream value-based banking. They should further study the impact of synergies in the short and long terms.

This study was carried out based on limited data and a limited study period due to the availability of data related to the VBIBs. The data analysis was restricted to a small number of Islamic banks selected from only three countries. The scope of the study should also include more than just the East Asian countries, and the sample size should be increased and more representative of the global Islamic banking sector. Thus, the forthcoming studies on this topic should be conducted based on more variables and a larger sample size selected from diverse geographical areas.