Abstract

Digitalization, new work and leisure concepts and global challenges are transforming the way we live. More stakeholders, including residents and entrepreneurs, actively participate in the implementation of alternative socio-economic concepts; as such, entrepreneurial ecosystems are seen as drivers of regional development. The research still lacks holistic approaches to the application of ecosystems in tourism destinations. Hence, the objectives of this article are to capture research on entrepreneurial ecosystems in tourism and, specifically, to derive a holistic model that integrates destination and location management across stakeholders. This research utilizes the method of a systematic literature review, starting with 597 articles on ecosystems. Following four stages of exploring the literature, the results show that most articles have been published in rather isolated fields of smart tourism or quality of life aspects. Based on the rather qualitative review that reveals specific ecosystem components, we propose a model of an “Ecosystem of Hospitality” (EoH). Focusing on stakeholder interaction and encounters, the EoH fosters the adoption of the entrepreneurial ecosystem to destinations in a dynamic approach. The practical implications are, for example, a broader consideration of various stakeholders, including the local population, and a switch in typical destination management tasks from mere tourism service production to regional development and living space management.

1. Introduction

Locations and destinations are in a state of transformation. The framework conditions of living and economic spaces are changing as a result of technological innovations and digitalization, new work concepts or dynamic developments in cities [1,2,3]. Destinations, in particular, are undergoing a fundamental transformation, with sustainability and resilience becoming central elements of a new understanding of travel [4,5], which results in a new role of tourism in the society and economy. More than ever, cities, municipalities and regions have the opportunity to put people at the heart of the discussions on spatial development and to involve a variety of stakeholders. Local actors take on creative responsibility and revitalize the cultural and creative scene [6]. A culture of personal encounters lays the foundation for sustainable location, destination and living space development and establishes a new relationship between hosts and guests.

From a conceptual perspective, the importance of tourism and leisure as soft location factors has often been taken into account [7,8] and is also shown by models of integrated location development [9,10,11], which define companies, workers, tourists and residents as core stakeholder groups. From a mix of entrepreneurs, young creatives, tradition-conscious residents, cultural workers and (international) guests, new concepts are emerging that break up previous structures and bring a transformation. The focus is no longer on the quality of experiences alone, but on the quality of life as well.

These new concepts shape the integration of entrepreneurs and the development of a lively start-up scene in the context of entrepreneurial ecosystems (henceforth referred to as ecosystems) [8,10,12,13,14]. With their innovative and creative charisma, these entrepreneurs are now also drivers of district design and contribute to the attractiveness of a location. The first adaptations to tourism [8,10,15] also show interfaces with the destination, e.g., in leisure-relevant services for the local population and tourists on the one hand, and for start-ups seeking a dynamic environment on the other.

However, the research lacks conceptualizations that display how an ecosystem in tourism destinations may look like, including business functions, output orientation, processes and encounters [16,17]. Similarly, the role of networks in the context of touristic, cultural and local development [18] as well as the interactions of guests with other stakeholders [19] need to be further elaborated. Lastly, there is a need to adopt the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach to creative tourism and culture-based contexts [18]. By investigating these research gaps, our research aims to re-conceptualize destination development and encourage a transformation of the tourism industry. To do so, the objective of this article is to adopt the ecosystem potentials at the destination level by answering the following research question:

What are the potentials of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach in destination development, and how can a holistic Ecosystem of Hospitality be conceptualized?

In contrast to strategic networks, our contribution aims to systemize current research on entrepreneurial ecosystems in the spatial setting of destinations to derive a model of an “Ecosystem of Hospitality” (EoH). In short, the EoH integrates the theoretical approaches of location, destination and living space management (Section 2; theoretical background). The systematic literature review (Section 3; methodology) unfolds the potential to increase the connectivity of multiple stakeholders (Section 4; results of the literature analysis). The derived model of the EoH (Section 5; discussion) recognizes the interrelatedness of local stakeholders across sectors and emphasizes the relationship and interactions between locals and guests. These are referred to as “hospitality”, exceeding the traditional definition of hospitality in terms of fare or accommodation provision (cf. Section 5). The present article proposes an integrated destination, location and living space development and, thus, (1) contributes to discussions of alternative approaches in tourism destinations, following contemporary changes and challenges, and (2) opens new potential research paths (Section 6; conclusion).

2. Theoretical Background: Managing Tourism Destinations in Transformation

2.1. Current Challenges of Destination Management

A destination is a “geographical space […] which a visitor (or visitor segment) chooses as their travel location. It contains all facilities essential for accommodation, gastronomy, entertainment/activity during the stay. Hence, it is that competition unit within incoming tourism that needs to be managed as a strategic business unit” (translated from German) [20] (p. 54). According to Wiesner [21], destination include aspects such as culture, sports, nature, cuisine, accommodation, health, local traditions, shopping, leisure, sightseeing or a transport and communication infrastructure. This understanding of destination management, therefore, requires an interplay of multiple stakeholders and a consideration of their various interests and demands.

The current challenges of destination management are manifold. Among them are global challenges such as societal change, demographic change or the digital transformation [22,23]. Recent discussions on resilient approaches aim to address these and provide solution attempts, in tourism and beyond [24]. The growing inequalities and income gaps between nationalities, genders or economic sectors are general issues and challenges that are not exclusive to tourism, but are particularly present in the industry due to the economic scope. Hence, alternative concepts are needed that focus on public welfare considerations [25].

A more tourism-specific issue in the context of experience creation is the development of authenticity and story-telling, which has become essential in tourism to individualize tourist offers [26]. This is, to some extent, connected to the emerging relationships between guests and locals, which can be built around pragmatic (i.e., economic), experiential (i.e., experience) or spiritual (i.e., hospitality) values [27]. Further challenges such as overtourism or the recent COVID-19 pandemic have shown that a relationship exists between tourism and the quality of life of residents within a city or region. The emergent discussions on overtourism and similar issues of mass tourism stimulate the need for an integrated, holistic development of the living space that allows for the participation and involvement of various stakeholder groups within the different processes and layers of destination and location management to meet the needs of individuals as well as society at large [28]. In doing so, experiences will be created for visitors and residents alike, local interest groups will be included in decision-making processes, and residents may benefit from the visitor economy and improved urban infrastructures [29].

It has been pointed out that destinations that aim to be competitive in a future global market not only need a strong brand, functioning infrastructure and professional distribution, but also committed entrepreneurs and a well-conceived innovation and product development [30]. Therefore, there is a need for a more holistic perspective of destination management that considers all actors and stakeholders.

2.2. The Role of Urban and Rural Development for Tourism

Regional development focuses on the improvement in socio-economic and ecological conditions within all types of regions, from urban to rural areas [31,32]. Hence, a distinction can be made between urban and rural development, whereby the overarching aim is to develop and improve living conditions in urban or rural areas.

In Europe and America, the relationship as well as the interaction between urban and rural areas has changed significantly, with industrialization and increasing economic growth. In the past, village regions were seen as a food and material storehouse for urban areas. In the age of globalization and the rise of the knowledge economy, rural areas in industrialized countries have developed into modern, diverse and creative places to live and spend leisure time [33]. Similar to urban areas, rural areas are always confronted with changing conditions, and megatrends such as global economic power (1), demographic and social shifts (2), accelerating urbanization (3), the rise of technology (4) and climate change and resource scarcity (5) have an impact on urban and rural development. Megatrends not only drive the transformation of the world, but can also be seen as one of the greatest challenges and opportunities for society [34]. In addition, there are discussions about multi-locality. Today’s society divides its everyday life into several locations, and living and working places are not always close to each other. Although this can prevent daily commuting or migration, demands and expectations for space (e.g., infrastructural connections, housing market) change and financial or psychological strains can arise for society. Nevertheless, multi-locality promotes participation in social and economic contexts and networks as well as the possibility of financial transfers [35].

Another consequence of multi-locality and increasing urbanization is urban fragmentation. Urban spaces, and thus urban life, have expanded further, and the boundaries between urban and rural areas have become blurred [36]. “Rural-urban linkages play a crucial role in the generation of income, employment and wealth” [37] (p. 20). However, the implications of this change for urban and rural development are, as of yet, unknown, and further research is needed. At the present time, the COVID-19 pandemic is the main concern in urban and rural development. New fields of action are arising and sustainable transformations in cities and villages can be driven forward. The COVID-19 pandemic offers the opportunity, for example, to question spatial use concepts, strengthen the resilience of urban and rural areas or criticize housing policy. In the context of the crisis, sustainable, resilient and health-oriented urban and rural development can be promoted, which should consider the changes in society, innovations in science and the economy, political changes as well as digitization. Nevertheless, the approach to a post-crisis period is still unclear [38].

Still, approaches can be found in science that propose practical ways forward. For example, Knieling’s [39] research shows that urban and rural planners are the pioneers of sustainable transformation. Similarly, the concept of the smart city, in which innovative technologies are used to further develop the city’s infrastructure and services, offers potential. However, the understanding of the smart city varies. It is understood as a future market, as a field of technological innovation or as a solution to existing energy and resource problems [40]. Thus, there is no universally valid definition of the smart city to date. According to Shcherbina and Gorbenkova [41], however, the following central elements of a smart city can be named: E-governance and citizen services (1), waste management (2), water management (3), energy management (4), urban mobility (5) and others, such as tele-medicine and education. With regard to tourism, the smart city represents a development platform that enables the establishment of a smart tourism destination. Here, the focus is on the intelligent use of information and communication technology by tourism stakeholders [42]. Finally, there is a mutual interaction between urban and rural development, and both areas can influence each other negatively as well as positively [43].

2.3. Concepts of Location Development

Wiesner [21] (p. 23) defines a business location a “a geographically or functionally defined area, where activities of the value creation process are taking place and being supported”. These activities encompass procurement, production, trade, services, education and science, as well as governmental institutions and programs, and result in outputs that are of interest for both internal and external players. Within locations, clearly defined economic districts aim to attract investors, businesses and workers. Two dominating district types are industrial districts and clusters. According to Becattini [44], an industrial district is “a socio-territorial entity which is characterised by the active presence of both a community of people and a population of firms in one naturally and historically bounded area. In the district […] community and firms tend to merge” [44] (p. 13). Similarly, a cluster is a “geographically proximate group of interconnected companies and associated institutions in a particular field [that] encompass an array of linked industries and other entities important to competition” [45] (p. 16).

Therefore, the functions and attributes of locations are manifold and can be economic, trade, technological, educational, leisure, health or of another nature. Locations that are perceived as attractive for investors or businesses often combine various attributes. The perceived quality of a location can also be derived from the quality of its hard and soft location factors, some of which are infrastructure (logistics, public transport or communication), political stability, social climate, quality of the workforce, the attraction of the domestic market, funding opportunities, labor costs, taxes, etc. [21].

As a more recent development, the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach, with its innovative character, can be seen as a driver of regional, local or sub-local—that is, neighborly—development and boost a location’s attractiveness. In such an ecosystem, there is a strong interdependence between different agents and factors, with entrepreneurial activity being the core output [46]. A similar concept is that of the entrepreneurial destination, allowing residents to use and enjoy facilities initially built for tourists, and startups and businesses to profit from a vibrant, dynamic social environment [10].

2.4. Integrative Approaches

One of the earliest attempts to establish an integrated location and destination management approach was made by Bieger et al. [20]. They replaced these terms with the concept of regional management, which combines societal, natural, technological and economic aspects, as well as resources, and the values and interests of various stakeholder groups, with tourists, residents and businesses being the most important ones. According to their model, an integrated approach consists of three management layers: normative management, which focuses on achieving viability and the development of a region; strategic management, which recognizes and utilizes potential in order to achieve success; and operative management, which focuses on success and profitability.

Pechlaner et al. [47] speak of different levels of integrated location and destination management, such as destination governance—that is, an integrated offer and coordination of actions—or regional governance, which refers to an inter-sectoral coordination of actions and a focus on regional competitiveness.

Another approach is that of place management, through which different factors, such as natural resources, regional or national framework conditions, transport and communication infrastructure, human capital, quality of life or economic infrastructure—the latter encompassing both tourism- and economy-related facilities—are combined with a complex management task [21]. This allows for place managers to cooperate with and involve numerous stakeholders, such as politician and political initiatives, governmental institutions, universities and educational providers, scientific and research institutions, businesses, economic associations, location and economic development agencies, tourism organizations, societal associations, media, religious institutions, accommodation providers, gastronomy, sport and leisure facilities, health institutions, cultural facilities or residents.

Integrated approaches such as these are increasingly gaining academic, political and economic attention, as the variety of soft and hard location factors are important to all relevant stakeholder groups: visitors, residents, entrepreneurs, businesses and workers.

3. Method: Systematic Literature Review

Following the research question, aiming to explore the potential of the ecosystem approach in destinations, this article chooses the method of a systematic literature review (SLR) to uncover existing structures in ecosystem research, as well as prevailing research gaps. The SLR can, therefore, collect research recommendations from other publications that also state the need for conceptual clarity across different ecosystem approaches. Research on ecosystems has been shown to be a highly dynamic field during the last five years [48], offering specific potential in tourism in the search for alternative approaches to location and destination management [10]. This SLR aims to frame the research field of ecosystems in tourism and to clarify the various concepts on a theoretical basis.

In comparison to a traditional narrative literature review, an SLR delivers a structured framework for classification and analysis. Without merely stating the quantitative data, such as bibliometric analysis, or picking facts from the researchers’ viewpoint, such as a narrative review, an SLR systematically delivers research gaps, definitions, and research characteristics in line with the research question [49,50]. As the SLR has gained attention in various research fields, it is now accepted as an independent research method [51]. In the context of tourism, the SLR was applied, e.g., in articles on adventure tourism [52], film tourism [53], sustainable tourism [54], positive psychology [55], innovation [56], customer satisfaction [57], or sports tourism [58]. As there is still emerging research on ecosystems in tourism, reviews from other business sectors provide an orientation, such as Wurth et al. [59], for ecosystem governance, or Cavallo et al. [48], for understanding local ecosystems. However, these reviews leave space for elaborations on ecosystem research in the tourism industry.

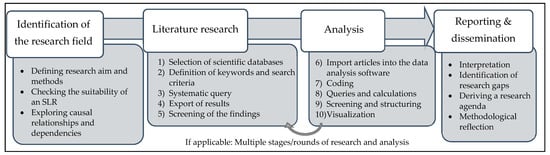

Reviews follow different processes according to different types of systematic reviews [51]. The SLR in this article was pursued as stated in Figure 1, in combination with a rather qualitative approach to content analysis, without complete bibliometric expression. Based on preliminary definitions of the relevant research area, the sections “literature research” and “analysis” provide ten steps to extract data. Therefore, central decisions regarding research fields and filters are made, followed by the definition of queries and keywords, leading to detailed steps on coding and visualization.

Figure 1.

The procedure of the qualitative Systematic Literature Review (SLR). Source: Thees [60].

In the first step of the SLR, Web of Science and Science Direct were selected as appropriate literature portals. They cover most of the research in business studies and deliver a satisfactory sample size. Critical filters in this query are the English language (1), publications since 2011 (2) and journal articles as sole publication type (3). The focus on articles guarantees scientific quality and availability. This query led to the search results in Table 1, including the respective shares of the search terms on the particular platform. The respective search queries are shown in Table 2 and represent a broad approach to elaborating the ecosystems, including various spellings. In addition to those results, a couple of articles were removed that followed a different ecosystem definition, e.g., ecological ecosystems.

Table 1.

The search results of the SLR.

Table 2.

The four screening stages of the SLR.

The final sample for the SLR comprises 597 articles as a starting point for subsequent analyses. Therefore, the authors decided to apply four screening stages that reflect a funnel in order to concretize the results and to be specific on every stage (Table 2). Starting with 597 articles on the meta-stage, a more quantitative analysis was conducted. Here, frequencies were primarily used to illustrate the research field. On the macro-stage, the focus was set on articles that include the tourism and hospitality industry. From a mathematical perspective, the clusters in this section were calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient, which measures the strength of the relations between two articles. The calculation across all articles was conducted with NVIVO. With this tourism-related sample, the meso-stage displays research characteristics based on frequencies, whereas more qualitative analyses were conducted on the micro-stage. Therefore, the micro-stage follows a qualitative content analysis that starts by identifying relevant information and clearing up, building categories and structuring a summary. Building upon those procedures, the next section will provide the results for each stage.

4. Results: Framing Ecosystem Research in Tourism

This SLR has four stages of concretization that follow the funnel in Table 2, starting with the meta-stage and concretizing the results towards the micro-stage. Subsequently, the results of the SLR are displayed on each stage.

4.1. Meta Stage: What Role do Tourism and Regional Aspects Play in Ecosystem Research?

The meta-stage reflects a quantitative description of the research field by broadly including all journal publications that were found (Table 2). This section aims to display the relevance of tourism and regional aspects in the broad research field of ecosystems by referring to publication dates, titles and journals.

Starting with an overview of the publication dates, Table 3 reveals the growth rates since 2017. A specialization of specific economic sectors can then be observed.

Table 3.

Publication dates of the reviewed articles.

The titles of the articles provide information about the handled topics (Table 4). Besides the keyword “ecosystem”, which is part of every title, it becomes clear that, according to the search filters, “business” and “entrepreneurship” are central keywords. In addition, we can also see that modeling or describing certain cases is an essential part of the articles, while, content-wise, there is a focus on digital/technology and knowledge/education. The term “tourism” (n = 7) is not included in the top findings; however, the further title terms “regional” (n = 32), “city” (n = 9), “local” (n = 8), “spatial” (n = 6), or “urban” (n = 4) definitely also shape the tourism sector as well.

Table 4.

Title keywords of the reviewed articles.

When analyzing the journals that published the selected articles, highly relevant journals can be found, such as Technological Forecasting and Social Change (26 articles), Sustainability (17), Journal of Business Research (17), Small Business Economics (14) and Journal of Cleaner Production (12). Together with other journals, ecosystem research is rooted in various disciplines and appears in journals on information and communication technology, policy, business research, or sustainability.

4.2. Macro Stage: Which Thematic Clusters Evolve in Tourism Ecosystem Research?

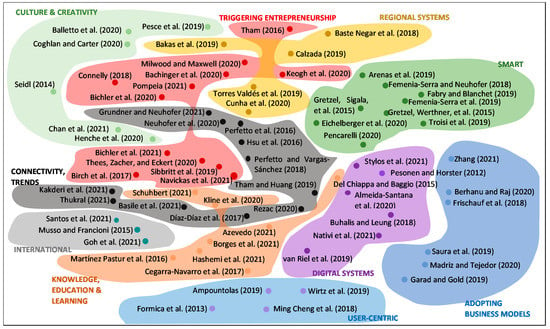

The next stage of our analysis proceeds with a smaller set of articles, as we selected articles with a direct relationship with tourism (Table 2). These 70 articles are essential to elaborate on the characteristics of ecosystem research in tourism. At first, the macro-stage reveals thematic clusters to capture the current research. Therefore, a cluster-building based on the similarity of full-text words is applied via Pearson Correlations. Figure 2 presents ten clusters, named according to the articles included in a particular cluster. Each cluster was calculated within NVIVO to have similarities and includes at least three articles. Nevertheless, an additional check was necessary to locate statistical outliners. In general, the clusters represent essential components of the ecosystem discussion by including smart and digital systems, knowledge, and education or connectivity. There are also clusters that recognize the role of the spatial system (regional and international) and that of culture and creativity. Although there are different approaches to defining the outcomes of an ecosystem, a couple of articles discover modes of triggering entrepreneurship within the ecosystem, in terms of innovation, sustainability, or economics. While analyzing the clusters, it becomes apparent that smartness has a rich history in ecosystem research in tourism, and this also supports the solid conceptual background within this cluster. Another factor that caused this increase in research is the sharing economy, which is part of the user-centric cluster but also includes various case studies across the other collections.

Figure 2.

Thematic clusters of relevant articles. Source: Own elaboration, articles = 70.

To further elaborate the thematic direction of ecosystem research in tourism, the keywords of the macro-stage articles were analyzed by number of appearances. The focus topics were technology, networks, managing, data, information, development, community, sharing, tourists, systems, or particular research methods, to name just a few.

4.3. Meso Stage: To What Extent Have Tourism Ecosystems Been Explored?

In terms of their methodology, the analyzed articles reveal a broad spectrum of applied tools and methods (Table 5). However, we can see a focus on qualitative research designs. In addition, there are a couple of articles that triangulated certain methods. Worth mentioning is the adaption of new methods from ethnography, which provide a different and more user-centric approach. It is also notable that several authors developed concepts rather than studying a field empirically. This was mainly the case in the field of smart and digital ecosystems, as in the solid conceptual work of Gretzel [13,61]. What appears to be underused to date is network analysis, despite its seeming appropriate for the localized and networked concept of an ecosystem. From a methodological perspective, the previous research clearly points to lifecycle or longitudinal studies aiming to capture the development of ecosystems [17,18,62,63]. In addition, present studies should be expanded to different markets and service sectors, as well as in different economic cultures [64,65]. When studying comprehensive and wide ecosystems, social network analyses are perceived as valuable [18,66].

Table 5.

The research methodology of relevant articles.

Looking at the scales (Table 6), where research was conducted geographically, helps to reveal certain clusters or gaps. In this regard, it is noticeable that many studies concentrate on Southern Europe, primarily Spain, Portugal or Italy. There are also comparative studies on an international scale that analyze at least two countries. As the ecosystem approach is a very localized one in tourism to date, many researchers focus on cities and specific regions. In addition, in some articles, the focus is on specific service providers or platforms. Future research may include the European Smart Cities, as a set of valuable case studies, showing progress in smart ecosystems.

Table 6.

Spatial scales of relevant articles.

The analyzed articles build upon various research needs and gaps and establish fields for future research. The following paragraph presents these research needs and gaps that mainly include hints on methodological improvements but also questions on the regional impact and further digitalization of the ecosystem.

Ecosystem research in tourism stresses the relevance of the region for the ecosystem and vice versa. Future research in this regard needs to include a variety of stakeholders and the local community [90]. However, ecosystems can provide interesting opportunities for micro-entrepreneurship or promote local networks, which should also be included in the research [17,18]. Furthermore, it would also be valuable to analyze how ecosystems work in rural creative tourism [18] or how external factors shape the development of ecosystems in general [66]. Although ecosystems mainly play a role in local contexts, future research can expand on the local–global continuum of ecosystems [62].

A third research field is based on the interactions that occur in ecosystems. This may be from the tourist’s perspective regarding interaction with the tourism service providers [117] or the relationship between DMOs and service providers [19].

Next, research gaps are described around the digital progress in ecosystems. In this regard, the technological development and the usability of machine learning and AI are at the center of the research needs [92,114]. A broad spectrum of experts needs to be involved in the research [103] to carefully balance human–computer interactions and retain trust and privacy [65,114]. The impact of technological progress on the ecosystem needs to be researched further [17].

In addition, further research needs are mentioned, such as the role of p2p platforms [107], the parallel systems of ecosystems [17], an analysis of ecosystem resources [81], policies on resilience, and entrepreneurial capability [122].

4.4. Micro Stage: What Are the Specific Drivers for Ecosystem Development and How Are They Characterized?

The final stage of the SLR analyzed the specific drivers of ecosystem development and their characteristics, as well as the clusters that are focused on. This part of the analysis revealed that the success factors of ecosystems have barely been investigated in the literature. The importance of digitization and single digital components for the whole ecosystem has been recognized early on [93]. The availability of knowledge, talent and other resources is also critical for a successful ecosystem; even the nature of the ecosystem itself constitutes its success, as continuous successes and failures and the resulting firm exits, workforce up-skilling and new formations continuously (internally) create and (externally) attract new resources [87]. However, ecosystems, together with local conditions and resources, also contribute to the success of entrepreneurs [62].

4.4.1. Ecosystems: A Definition

Subsequently, the definitions of ecosystems, ecosystems in tourism and the ecosystem components in tourism will be analyzed to capture the central components and potentials and reach a consensus. This will provide a foundation for the development of an integrated concept.

The idea of classifying and conceptualizing business and entrepreneurial environments as ecosystems is derived from biological ecosystems, which encompass the “biotic community, its physical environment, and all the interactions possible in the complex of living and nonliving components” (Acs et al. [46], cited in Eichelberger et al. [42] (p. 320)). This approach was later adopted for the definition of interactions and interdependencies in economic and entrepreneurial environments. Such ecosystems are formed of a number of formal, physical, market and cultural framework conditions, as well as systemic conditions, such as networks, intermediaries, talent, knowledge, leadership and finance.

This has led to the establishment of the “Entrepreneurial Ecosystem”, which is defined as “a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship in a particular territory” (Stam and Spigel [123], cited in Bichler et al. [62] (p. 2)). Within entrepreneurial ecosystems, several different actors are of importance. The main actors are entrepreneurs, who are driven by a vision and participate in the industry with their innovative ideas [66]. They are often attracted by local and regional working and living conditions, and can contribute to the economy and development of the place at which they work [70]. Other central actors in entrepreneurial ecosystems are businesses, which often have an entrepreneurial culture and provide resources to other ecosystem stakeholders. The third important actors are organizations and governmental institutions, such as trade associations, research and educational institutions, investors or regulating bodies, which add to the success of businesses and entrepreneurs and provide many of the aforementioned conditions [109].

Similar to entrepreneurial ecosystems, business ecosystems are local networked systems where multiple firms coexist, cooperate and compete; are interconnected and, partly, depend on each other; and form a dynamic structure that can adapt and develop [112]. This interplay of competition and cooperation, which is also referred to as co-evolution, facilitates organizational growth and strengthens the local and regional economy [81]. Hence, both entrepreneurial and business ecosystems with their surrounding local environments are seen as drivers of regional development [62]. Furthermore, some scholars view ecosystems that consist mainly of corporate and government actors and policies as important elements of tourist destinations, alongside their territory, tourism companies and the local community [78].

4.4.2. Ecosystems in Tourism

As a subdivision of both entrepreneurial ecosystems and the tourism industry, tourism ecosystems consider the perspectives and interests of all relevant stakeholders such as businesses, residents, governing bodies and visitors. Among the major reasons for this approach is the impact that visitors of a city have on residents and the residents’ feedback as an important tool to support the different stakeholders of the touristic ecosystem [74]. Furthermore, entrepreneurial ecosystems in tourism can also help reshape management models and tourism products and, through entrepreneurial activities, and enable sustainable development in tourism [84] and beyond.

Considering the findings of the SLR, there appears to be no specific definition of tourism ecosystems, as most research focuses on digital and smart aspects that are gaining increasing attention in destinations and tourist environments. The smart urban ecosystem approach is described as a complex urban ecosystem that connects the destination with the smart city [100]. Recognizing tourism systems as smart ecosystems can help to integrate resources more sustainably, increase the understanding of the strategic impact of information and communication technologies along the entire customer journey [117] and meet travelers’ need for information and communication, not only before but also during the travel phase [78].

Creating a digital environment and implementing the technological infrastructure into a destination helps achieving a stronger cooperation and increasing the share of knowledge and open innovation between all destination stakeholders [93]. Such cooperation and knowledge exchange also enable the tourism industry to “engage and interact with the public, create conversations, and establish relationships” to deal with new trends and developments that impact society, travel and local communities [85] (p. 75). This, ultimately, leads to “more convenient, safe, exciting and sustainable living spaces for both residents and tourists […] and even greater opportunities for new services, business models and markets” [61] (p. 185).

More recently, attempts have been made to combine both entrepreneurial and tourism ecosystems and add aspects such as lifestyle or quality of life to discussions about entrepreneurial ecosystems [15]. A further modification is the concept of Entrepreneurial Destinations that “adds the perspective of living and leisure [and] defines economic roles and activities by highlighting urban attractiveness” [10] (p. 171), which also facilitates the complex coordination, sustainable management and flexible handling of the major stakeholders, namely, entrepreneurs, residents and visitors [10]. Among the core ideas that set entrepreneurial destinations apart from other approaches, are co-concepts such as co-working, co-living or co-experience, which call for an integration of working, living and leisure environments. One way of achieving this integration is the concept of “living labs” that enables dialogue and exchange between all the stakeholders of a place [104].

Given the lack of a definition of tourism ecosystems and the strong academic focus on smart destinations and digital tourism ecosystems that was revealed by the SLR, there is a need for more holistic perceptions of tourism ecosystems and, on a spatial scale, destination ecosystems beyond the focus on technological aspects.

4.4.3. Components of a Tourism Ecosystem

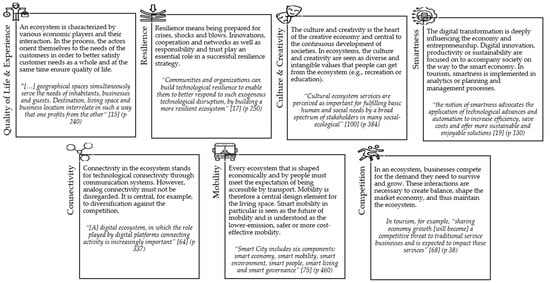

Following theoretical diversity and insights from the SLR, the components that a tourism ecosystem should contain are illustrated in Figure 3. The tourism ecosystem is very diverse and includes the following areas: Quality of Life and Experience (1), Resilience (2), Culture and Creativity (3), Smartness (4), Connectivity (5), Mobility (6) and Competition (7). These components will also be applied to our spatially derived model proposition (cf. Section 5).

Figure 3.

Components of the Tourism Ecosystem. Source: Own elaboration, based on [15,17,19,64,68,75,100].

In terms of understanding the ecosystem in tourism, the results indicate that the “Quality of Life and Experience” and “Smartness” components are central. Therefore, they will be described in more detail. Fabry and Blanchet [100] emphasize that tourism is not only a revenue driver, job creator, or improver of local infrastructure, but also positively contributes to the quality of life of the local population. It is an economic factor that generates significant per capita value in many places. Consequently, tourism creates entrepreneurial opportunities for various stakeholders, e.g., tourism operators, travelers, or residents [70]. However, the current discussions around over-tourism, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic’ impact on tourism, indicate that tourism acceptance by the local population is no longer present in some destinations. The understanding of other people needs to be rebuilt and fostered to positively implement tourism with authentic experiences [16]. “A smart tourism ecosystem [...] can be defined as a tourism system that takes advantage of smart technology in creating, managing and delivering intelligent tourist services/experiences and is characterized by intensive information sharing and value co-creation” [13] (p. 560). As this definition emphasizes, smart technologies, such as sensors or big data, are of fundamental importance for the tourism of the future in the course of advancing digitalization. In this context, applied smartness is the responsibility of a wide range of stakeholders—e.g., the government, tour operators and travel agents, transportation providers, restaurants and hotels, local populations, and travelers—with the positive side effect of encouraging public engagement [74]. Furthermore, Pencarelli [78] emphasizes that smartness strengthens competitive advantages, but must not neglect sustainability or negatively affect the quality of life of the local population. Moreover, digital technology, apps, and Big Data must not become a force that creates pressure rather than vacation anticipation.

5. Discussion

The existing ecosystem approaches focus on entrepreneurial and business environments as well as, in a tourism context, smart and creative systems. A newer approach is that of the entrepreneurial destination, which considers the perspectives of entrepreneurship and leisure. However, a holistic concept, which also considers essential components such as residents’ involvement, local networks, touristic and local development, guest–stakeholder encounters or tourism- and service-oriented entrepreneurs, as well as the components outlined in the analysis (cf. Section 4.4.3), was needed. The first attempt in that direction, the Ecosystem of Hospitality (EoH), will be based on the existing ecosystem concepts and the results of the present study. The EoH refers to the spatial scale of destinations.

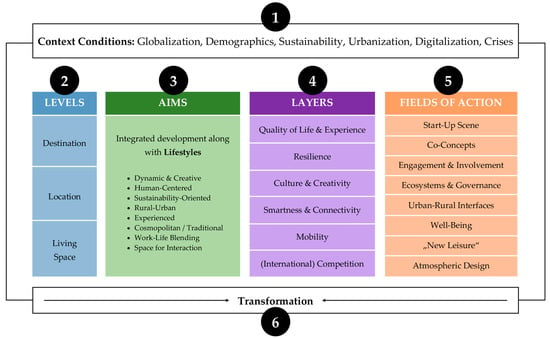

5.1. Model Overview

The aim of the EoH is the integrated development of destinations, locations and living spaces, along with lifestyles and newly arising trends, to both strengthen the customer orientation and underline the dynamics between global trends and local offers, which altogether create new spaces for encounters. Figure 4 reveals the model of the EoH. Context conditions (1) affect the different levels of the destination. As a consequence, an integrated development together with lifestyles (3) has to take place. Accompanied by content layers (4) such as smartness or mobility, some of the future requirements and fields of action (5) for a flexible destination management emerge. Such actions eventually cause a transformation towards a dynamic destination, location and living space, which will affect the resilience of these places. The sequence can vary from destination to destination. The following elaborations are based on the developed model of the EoH.

Figure 4.

Model of the Ecosystem of Hospitality (EoH). Source: Own elaboration.

The EoH is shaped by different layers of quality regarding its requirements and values, which characterize it and make it unique. The innovative spirit, the enthusiasm for pioneering (cf. Section 1 and Section 2.3), or the wish for better quality, which is broadly shared across the network, make it an ecosystem in the first place. The EoH differs from other ecosystems, especially in the nature of tourism, by considering the experience of encounters and relationships (cf. Section 2.1) as expressions of humanity. In this context, the encounters allow for a reflection of one’s being and doing.

The integration of living space, location and destination fosters alternative concepts and new fields of action, which enable transformation via lifestyle orientation and a cross-stakeholder dynamic. Essential for this development is internal and external communication through umbrella branding, corporate branding or destination marketing that unites the diversity of local development in a common brand design (cf. Section 2.1).

5.2. The Relationship between EoH Actors

As shown in Section 1 and Section 4, both integrated destination and location management approaches, as well as ecosystems, incorporate a number of actors and stakeholders, such as residents, visitors, entrepreneurs, businesses and government bodies. The interrelatedness of actors in the proposed EoH can be imagined as concentric circles that each illustrate different, overlapping dimensions. With the EoH, the idea of interconnected actors (cf. Section 2.1) is further developed and the quality of the relationships between these actors is put at the heart of the discussion, with a particular focus on hosts, who can be either tourist service providers or local residents, and guests. This dimension of hospitality is the core nature of tourism, a pivotal indicator of satisfaction, given that both the host and the guest were positively affected by this exchange and experienced some form of interaction and reciprocation. This requires a certain depth of the relationship, which can only be achieved through a value-based relationship between the host and guest.

An additional factor concerns hospitality, in other words, the quality of encounters, which aims to arouse enthusiasm and excitement. This can occur through the creation of authentic experiences of encounters (cf. Section 2.1) enabled by the experience design. The quality of encounters refers to the quality of experiences (in terms of events, adventures or experience-seeking; cf. German ‘Erlebnis’) and single moments, whereas the quality of relationships refers to the quality of experience (in terms of knowledge gained; cf. German ‘Erfahrung’) and the depth and impact of encounters. Referring to the service chains in tourism, the quality of services through professional service providers (cf. Table 4) is essential. This part of the ecosystem is strongly geared toward touristic services and, hence, is of major importance for the EoH. However, the ecosystem can only function well if its touristic parts are in constant balance with its non-touristic parts. The final outcomes of the model affect the quality of life (cf. Section 2.1 and Section 2.4) from the perspective of local residents, as well as organizations and institutions, which make essential contributions to the atmosphere of the place.

5.3. The Layers and Fields of Action

The requirements for flexible destination and location management are manifold. As highlighted by the elaborations in Section 2.2, the attractiveness of destinations and living spaces is becoming increasingly important. Similar to attractive locations [21], such places combine various attributes that are perceived as attractive. Implementing a variety of these attributes should, first and foremost, enhance the quality of life and experience quality, and even support the understanding of these two concepts as complementary to each other. Entrepreneurs, in particular, are increasingly searching for places with attractive environments for both work and life [70]. This underlines the transformation of especially urban places [40] and, therefore, new concepts are needed to create attractive spaces.

As detailed in Section 2.2, the aspect of human behavior is becoming a focus of urban and rural discussions. Concepts of culture, personality, psychology, and action are being looked at more intensively to better understand society’s behavioral factors and to design development perspectives. This means that urban and rural development should not only focus on material aspects such as economic growth, but also on human-centered areas such as well-being [124]. At the same time, strengthening citizen engagement and participation has become a key element (cf. Table 6) [125,126]. The successful involvement of all stakeholders can be realized via open external and internal communication. Conversely, a holistic living space development approach can foster the interest of residents and locals in participatory processes [28].

These EoH components are improved and further developed by smart concepts. Smartness and connectivity play a major role in urban and rural development, as information and communication technologies are essential for the local, digital economy and enable better collaboration between tourism businesses. The smart city approach offers a way forward in terms of urban and rural planning (cf. Section 2.2); thus, they are among the essential components of ecosystems, as outlined in the macro-stage analysis. In the context of digitization, startups play a major role in the attractiveness of a location. This is supported by earlier research that highlights both the growing omnipresence of technology [34], which corresponds with the present research that lists “digital” as the most frequent keyword in the ecosystem literature (cf. Table 4), and smartness, digital systems and connectivity as some of the most explored thematic clusters (cf. Figure 2 and Section 4.4.2 and Section 4.4.3).

As an interdisciplinary development approach, the concept of resilience can facilitate the flexibility and adaptability of a region. This was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic to achieve sustainable development [38]. The dynamics resulting from resilience foster the creation of new cultural and creative offers that manifest in New Leisure or a variety of co-concepts. The latter contribute to an intensified culture of encounters between local residents and guests (Section 5.2), unfolding an exchange of ideas. These co-concepts are co-created by entrepreneurs, creative minds, guests and locals, and have already found their way into the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach [10]. In turn, these newly arising creative urban spaces may even attract startups, digital companies and highly skilled workforce, which again strengthens the quality of an economic location [21]. The integration of those entrepreneurs and the development of a lively startup scene are increasingly discussed in the context of ecosystems (cf. Table 4; Figure 2). With their innovative and creative aura, such ecosystems complement district development and, together with industrial districts or clusters (cf. Section 2.3), contribute to the attractiveness and development of a place. They also foster productive entrepreneurship, leading to positive reciprocity between entrepreneurs and ecosystems [62].

This increasing urbanization requires new and alternative mobility concepts that are adjusted to both everyday life and leisure. Autonomous mobility or the platform and sharing economy open new opportunities for startups. These have often been described as both important elements of ecosystems and drivers of economic development (cf. Section 4). The foundations of a dynamic location, destination and regional development are laid by the different life models and areas of conflict of urban–rural interfaces.

An efficient governance, the development of regional value chains, the provision of basic services and the consideration of global megatrends are important in the global competition of locations and tourist destinations. The present research detected a lack of research on ecosystems focusing on international competition (cf. Figure 2). Referred to as hyper-dynamic competition by Bieger et al. [127], this approach requires product and process innovation, consideration of milieus and organizational learning [30] and, thus, a further extension of Pechlaner et al.’s [47] destination governance approach. This may be achieved by applying integrative and creative concepts such as hospitality, i.e., a welcoming culture that is formed by the relationships and interactions between locals and guests, and atmospheric design, which refers to the atmosphere and physical qualities of a place.

6. Conclusions

Based on global challenges, recent trends in the context of tourism and lifestyles, and the role of entrepreneurial ecosystems as drivers of local and regional development, the aim of this article was to conceptualize the existing literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems and derive a holistic, integrated model for destination and location management. This was achieved via a systematic literature review.

Our developed model integrates the destination level, location level and living space level into a joint approach. We found seven components that we regard as essential to ecosystem development in destinations: Quality of Life and Experiences (1), Resilience (2), Culture and Creativity (3), Smartness (4), Connectivity (5), Mobility (6) and Competition (7). They constitute the “Layers” of our derived model (cf. Figure 4). A variety of “Fields of Action”, namely, the Startup Scene, Co-concepts, Engagement and Involvement, Ecosystems and Governance, Urban–Rural Interfaces, Well-Being, New Leisure, and Atmospheric Design, illustrate some of the requirements that we found to play a major role in the development of an Ecosystem of Hospitality (EoH), which considers residents’ involvement, local networks, tourist and local development, guest–resident encounters and entrepreneurial innovations alike.

By perceiving tourism as a complex ecosystem of hospitality, we call to carefully understand the impacts and effects regarding tourism and how every individual, company and state is situated in this interdependent system. Understanding, learning and adapting are certainly critical competencies for the competitiveness of each component. On the one hand, the ecosystem approach assists in exploring the manifold relations. On the other hand, it helps to overcome crises in more joint and cooperative actions. Reflecting trends in our society, an ecosystem should be both open to innovate and adapt, and critical to traditional, alternative and prospective models.

Our article contributes to the various academic and practical discussions and developments. First, it enhances the understanding of holistic destination, location and living space management approaches, and promotes the idea of their conflation. The different levels of our developed EoH model, the aims, layers, and fields of action, lay an important foundation for the integrated development of destinations, locations and living spaces. Second, the article answers recent calls for adopted tourism and destination concepts in light of overtourism or debates on sustainability and transformation. Third, it supports the increasing academic and professional attention given to hospitality beyond the traditional scope, which is limited to providing fare or accommodation.

From a methodological perspective, our article is limited by its focus on tourism-related publications. The applicability of the EoH needs to be investigated by gathering primary data. Another limitation is the applied search filters on language, publication date and publication type, as well as the usage of specific literature portals, which may have excluded additional relevant literature from the SLR. From a theoretical perspective, our holistic destination, location and living space management approach is limited by its derivation from destination and entrepreneurial ecosystem concepts. Thus, additional components that are perceived as essential in the context of economic locations or the living space of residents may be further strengthened in our EoH model.

To further explore the potentials, relevance and development of the proposed EoH, future research may focus on the following topics:

- The creation of an EoH governance structure;

- The role of mobility concepts, both existing and alternative ones, in integrated destination and location management approaches;

- The role of new tourism trends, such as recreational or spiritual tourism, in destination and living space development;

- The inclusion of and interactions between various local and regional stakeholders in ecosystem discussions;

- The role of stakeholder issues and interests such as privacy, data protection or trust, especially in the context of growing digitization;

- The consideration of components that are perceived as essential in an economic location or in the living space of residents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P., J.P., H.T. and N.O.; methodology, H.T.; software, H.T.; validation, J.P., H.T. and N.O.; formal analysis, J.P., H.T. and N.O.; investigation, J.P., H.T. and N.O.; resources, H.P.; data curation, H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., H.T. and N.O.; writing—review and editing, H.P., J.P., H.T. and N.O.; visualization, H.T. and N.O.; supervision, H.P.; project administration, H.P.; funding acquisition, H.P. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The open access publication of this article was supported by the Open Access Fund of the Catholic University Eichstaett-Ingolstadt.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Suryani, A.; Soedarso, S.; Rahmawati, D.; Endarko, E.; Muklason, A.; Wibawa, B.M.; Zahrok, S. Community-Based Tourism Transformation: What Does the Local Community Need? IPTEK J. Proc. Ser. 2021, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.M. Human flourishing, tourism transformation and COVID-19: A conceptual touchstone. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetto Doorly, V. Megatrends Defining the Future of Tourism; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Espiner, S.; Orchiston, C.; Higham, J. Resilience and sustainability: A complementary relationship? Towards a practical conceptual model for the sustainability–resilience nexus in tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1385–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiripour, A.; Rahimi, E.; Shabanpour, R.; Mohammadian, A.K. How is COVID-19 reshaping activity-travel behavior? Evidence from a comprehensive survey in Chicago. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innerhofer, E.; Pechlaner, H.; Borin, E. (Eds.) Entrepreneurship in Culture and Creative Industries; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thießen, F. Zum Geleit: Weiche Standortfaktoren—Die fünf Sichtweisen. In Weiche Standortfaktoren: Erfolgsfaktoren Regionaler Wirtschaftsentwicklung Interdisziplinäre Beiträge zur Regionalen Wirtschaftsforschung; Thießen, F., Cernavin, O., Führ, M., Kaltenbach, M., Eds.; Duncker & Humblot: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pechlaner, H.; Thees, H.; Eckert, C.; Zacher, D. Vom Entrepreneurship Ecosystem zur Entrepreneurial Destination—Perspektiven einer Standortentwicklung am Beispiel der Freizeitszene München. In Service Business Development; Bruhn, M., Hadwich, K., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 477–507. [Google Scholar]

- Destination und Lebensraum; Pechlaner, H. (Ed.) Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thees, H.; Zacher, D.; Eckert, C. Work, life and leisure in an urban ecosystem—Co-creating Munich as an Entrepreneurial Destination. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieger, T. Kompetenzorientierte kommunale Standortstrategie. In Gemeindemanagement in Theorie und Praxis; Lengwiler, C., Ed.; Rüegger: Chur, Switzerland; Zürich, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 445–466. ISBN 9783725307012. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D. The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economy policy: Principles for cultivating entrepreneurship. Babson Glob. 2011, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gretzel, U.; Werthner, H.; Koo, C.; Lamsfus, C. Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B.; Harrison, R. Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bachinger, M.; Kofler, I.; Pechlaner, H. Sustainable instead of high-growth? Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in Tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henche, B.G.; Salvaj, E.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milwood, P.A.; Maxwell, A. A boundary objects view of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, F.E.; Duxbury, N.; Vinagre de Castro, T. Creative tourism: Catalysing artisan entrepreneur networks in rural Portugal. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 731–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Neuhofer, B.; Ivars-Baidal, J.A. Towards a conceptualisation of smart tourists and their role within the smart destination scenario. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bieger, T.; Beritelli, P. Management von Destinationen, 8th ed.; Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag: München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, K.A. Professionelles Standort-und Destinationsmanagement: Instrumentarien und Praxisbeispiele Für Erfolgreiches Place-Management und-Marketing; Erich Schmidt Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-503-19562-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pechlaner, H.; Habicher, D. (Eds.) Transformation und Wachstum: Alternative Formen des Zusammenspiels von Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft; Springer Gabler Verlag: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thees, H.; Störmann, E.; Thiele, F.; Olbrich, N. Shaping digitalization among German tourism service providers: Processes and implications. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2021, 7, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.M.; Lew, A.A. Understanding tourism resilience: Adapting to social, political, and economic change. In Tourism, Resilience, and Sustainability: Adapting to Social, Political, and Economic Change; Cheer, J.M., Lew, A.A., Eds.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2018; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. The effects of tourism on income inequality: A meta-analysis of econometrics studies. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Melissen, F.; Font, X.; Gkritzali, A. Designing for experiences: A meta-ethnographic synthesis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2971–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, X.; Davari, D.; Park, S. Transforming the guest–host relationship: A convivial tourism approach. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, D.; Pechlaner, H.; Olbrich, N. Strategy is the art of combining short- and long-term measures—Empirical evidence on overtourism from European cities and regions. In Overtourism—Tourism Management and Solutions; Pechlaner, H., Innerhofer, E., Erschbamer, G., Eds.; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Chan, C.-S. Needs, drivers and barriers of innovation: The case of an alpine community-model destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Worku, H.; Lika, T. Urban and regional planning approaches for sustainable governance: The case of Addis Ababa and the surrounding area changing landscape. City Environ. Interact. 2020, 8, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Regional, Rural and Urban Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/regional/ (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Cars, G. Future urban-rural relationship in China: Comparison in a global context. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2010, 2, 396–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. Megatrends. Available online: https://www.pwc.co.uk/issues/megatrends.html (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Danielzyk, R.; Dittrich-Wesbuer, A. Multilokalität in der Stadt- und Regionalentwicklung. In Multilokale Lebensführungen und räumliche Entwicklung—Ein Kompendium; Danielzyk, R., Dittrich-Wesbuer, A., Hilti, N., Tippel, C., Eds.; Verlag der ARL—Akademie für Raumentwicklung in der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft: Hannover, Germany, 2020; pp. 196–202. [Google Scholar]

- López-Goyburu, P.; García-Montero, L.G. The urban-rural interface as an area with characteristics of its own in urban planning: A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 43, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkoyunlu, S. The Potential of Rural–Urban Linkages for Sustainable Development and Trade. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Policy 2015, 4, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbe, J.; Bendlin, L.; Riechel, R.; Bartke, S.; Eckert, K.; Fahrenkrug, K.; Melzer, M.; Blecken, L.; Reiss, J.; Ferber, U.; et al. Memorandum Post-Corona-Stadt. Für Eine Suffiziente und Resiliente Entwicklung von Städten und Regionen; BMBF: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Knieling, J. Akteure und ihre Beiträge zur großen Transformation in ausgewählten Handlungsfeldern. Stadt- und Raumplanerinnen und—Planer als Pioniere nachhaltiger Transformation. In Nachhaltige Raumentwicklung für die Große Transformation—Herausforderungen, Barrieren und Perspektiven für Raumwissenschaften und Raumplanung; Hofmeister, S., Warner, B., Ott, Z., Eds.; Verlag der ARL—Akademie für Raumentwicklung in der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft: Hannover, Germany, 2021; pp. 172–182. [Google Scholar]

- Libbe, J. Smart City: Leitbild integrierter Stadt- und Regionalentwicklung? Disp.—Plan. Rev. 2014, 50, 76–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbina, E.; Gorbenkova, E. Smart City Technologies for Sustainable Rural Development. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 365, 022039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichelberger, S.; Peters, M.; Pikkemaat, B.; Chan, C.-S. Entrepreneurial ecosystems in smart cities for tourism development: From stakeholder perceptions to regional tourism policy implications. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P.; Havadi-Nagy, K.X.; Maroşi, Z. Tourism as a driving force in rural development: Comparative case study of Romanian and Austrian villages. Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2016, 64, 203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Becattini, G. The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. Rev. D’écon. Ind. 2017, 157, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Gobal Economy. Econ. Dev. Q. 2000, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Stam, E.; Audretsch, D.B.; O’Connor, A. The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechlaner, H.; Raich, F.; Kofink, L. Elements of Corporate Governance in Tourism Organizations. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2011, 6, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, A.; Ghezzi, A.; Balocco, R. Entrepreneurial ecosystem research: Present debates and future directions. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 1291–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitchenham, B. Procedures for Performing Systematic Reviews No. 33; Keele University: Keele, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D.A., Bryman, A., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Edwards, D.; Darcy, S.; Redfern, K. A Tri-Method Approach to a Review of Adventure Tourism Literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 8, 109634801664058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cardoso, L.; Estevão, C.; Fernandes, C.; Alves, H. Film induced tourism: A systematic literature review. TMS 2017, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, R.W.; Thok, S.; O’Rourke, V.; Pearce, T. Sustainable tourism and its use as a development strategy in Cambodia: A systematic literature review. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcês, S.; Pocinho, M.; Jesus, S.N.; Rieber, M.S. Positive psychology and tourism: A systematic literature review. Tour Manag. Stud 2018, 14, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomezelj, D.O. A systematic review of research on innovation in hospitality and tourism. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Mngt. 2016, 28, 516–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V.; Rudchenko, V.; Martín, J.-C. The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction in Tourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 24, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbold, V.; Thees, H.; Philipp, J. The Host Community and Its Role in Sports Tourism: Exploring an Emerging Research Field. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurth, B.; Stam, E.; Spigel, B. Toward an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Research Program. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thees, H. Towards Local Sustainability of Mega Infrastructure: Reviewing Research on the New Silk Road. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bichler, B.F.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M.; Petry, T.; Clauss, T. Regional entrepreneurial ecosystems: How family firm embeddedness triggers ecosystem development. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Piterou, A.; Khoo, S.L.; Lean, H.H.; Hashim, I.H.M.; Lane, B. An innovative social enterprise: Roles of and challenges faced by an arts hub in a World Heritage Site in Malaysia. City Cult. Soc. 2021, 25, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampountolas, A. Peer-to-peer marketplaces: A study on consumer purchase behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2019, 2, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riel, A.C.; Zhang, J.J.; McGinnis, L.P.; Nejad, M.G.; Bujisic, M.; Phillips, P.A. A framework for sustainable service system configuration. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, B.F.; Kallmuenzer, A.; Peters, M. Entrepreneurial ecosystems in hospitality: The relevance of entrepreneurs’ quality of life. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Córdoba-Pachón, J.R.; García-Pérez, A. Tuning knowledge ecosystems: Exploring links between hotels’ knowledge structures and online government services provision. J. Technol. Transf. 2017, 42, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Mat Roni, S.; Bannigidadmath, D. Thomas Cook(ed): Using Altman’s z-score analysis to examine predictors of financial bankruptcy in tourism and hospitality businesses. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Santana, A.; David-Negre, T.; Moreno-Gil, S. New digital tourism ecosystem: Understanding the relationship between information sources and sharing economy platforms. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.; Duffy, L.; Clark, D. Fostering tourism and entrepreneurship in fringe communities: Unpacking stakeholder perceptions towards entrepreneurial climate. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, A. Cultural ecosystem services and economic development: World Heritage and early efforts at tourism in Albania. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.P.; Lopes, J.M.; Carvalho, C.; Vieira, B.M.M.; Lopes, J. Education as a key to provide the growth of entrepreneurial intentions. Educ. Train. 2021, 63, 809–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, C.; Lichy, J.; Mulholland, G.; Kachour, M. An enquiry into potential graduate entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arenas, A.E.; Goh, J.M.; Urueña, A. How does IT affect design centricity approaches: Evidence from Spain’s smart tourism ecosystem. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, K.; Raj, S. The trustworthiness of travel and tourism information sources of social media: Perspectives of international tourists visiting Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, V.; Capobianco, N.; Vona, R. The usefulness of sustainable business models: Analysis from oil and gas industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Leung, R. Smart hospitality—Interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 71, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencarelli, T. The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J.; So, K.K.F.; Mody, M.A.; Liu, S.Q.; Chun, H.H. Platforms in the peer-to-peer sharing economy. J. Serv. Manag. 2019, 30, 452–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, A. When Harry met Sally: Different approaches towards Uber and AirBnB—An Australian and Singapore perspective. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2016, 16, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfetto, M.C.; Vargas-Sanchez, A.; Presenza, A. Managing a Complex Adaptive Ecosystem: Towards a Smart Management of Industrial Heritage Tourism. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2016, 4, 243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Nativi, S.; Mazzetti, P.; Craglia, M. Digital Ecosystems for Developing Digital Twins of the Earth: The Destination Earth Case. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhbert, A. From Knowledge-Pools to Activated Networks: A Conceptual Approach to Absorptive-Capacities in a Rural Destination of Azerbaijan. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 20, 2150019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Valdés, R.M.; Lorenzo Álvarez, C.; Castro Spila, J.; Santa Soriano, A. Relational university, learning and entrepreneurship ecosystems for sustainable tourism. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 905–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madriz, S.; Tejedor, S. Analysis of Effective Digital Communication in Travel Blog Business Models. Commun. Soc. 2020, 33, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletto, G.; Milesi, A.; Ladu, M.; Borruso, G. A Dashboard for Supporting Slow Tourism in Green Infrastructures. A Methodological Proposal in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, A. How can the entrepreneurship ecosystem in Guyana impact the tourism industry by 2025? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femenia-Serra, F.; Neuhofer, B. Smart tourism experiences: Conceptualisation, key dimensions and research agenda. Investig. Reg.-J. Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rezac, F. Addressing Conceptual Randomness in IoT-Driven Business Ecosystem Research. Sensors 2020, 20, 5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, V.; Ramos, P.; Sousa, B.; Valeri, M. Towards a framework for the global wine tourism system. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Anderson, C.K.; Zhu, Z.; Choi, S.C. Service online search ads: From a consumer journey view. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhofer, B.; Magnus, B.; Celuch, K. The impact of artificial intelligence on event experiences: A scenario technique approach. Electron. Mark. 2020, 31, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G.; Baggio, R. Knowledge transfer in smart tourism destinations: Analyzing the effects of a network structure. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Díaz, R.; Muñoz, L.; Pérez-González, D. Business model analysis of public services operating in the smart city ecosystem: The case of SmartSantander. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2017, 76, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Formica, A.; Missikoff, M.; Pourabbas, E.; Taglino, F. Semantic search for matching user requests with profiled enterprises. Comput. Ind. 2013, 64, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischauf, N.; Horn, R.; Kauerhoff, T.; Wittig, M.; Baumann, I.; Pellander, E.; Koudelka, O. NewSpace: New Business Models at the Interface of Space and Digital Economy: Chances in an Interconnected World. New Space 2018, 6, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A. Using social media photos as a proxy to estimate the recreational value of (im)movable heritage: The Rubjerg Knude (Denmark) lighthouse. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 2283–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, J.R.; Reyes-Menendez, A.; Palos-Sanchez, P.; Filipe, F. Discovering UGC Communities to Drive Marketing Strategies: Leveraging Data Visualization. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2019, 7, 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Infrastructuralization of Tik Tok: Transformation, power relationships, and platformization of video entertainment in China. Media Cult. Soc. 2021, 43, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabry, N.; Blanchet, C. Monaco’s struggle to become a smart destination. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 672–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A.; Carter, L. Serious games as interpretive tools in complex natural tourist attractions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Pastur, G.; Peri, P.L.; Lencinas, M.V.; García-Llorente, M.; Martín-López, B. Spatial patterns of cultural ecosystem services provision in Southern Patagonia. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundner, L.; Neuhofer, B. The bright and dark sides of artificial intelligence: A futures perspective on tourist destination experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, I. Local entrepreneurship through a multistakeholders’ tourism living lab in the post-violence/peripheral era in the Basque Country. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastenegar, M.; Hassani, A.; Bafruei, M.K. Thematic Analysis of creative tourism: Conceptual model design. Amazon. Investig. 2018, 7, 541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, S.S.; Amoozad Mahdiraji, H.; Azari, M.; Razavi Hajiagha, S.H. Causal modelling of failure fears for international entrepreneurs in tourism industry: A hybrid Delphi-DEMATEL based approach. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.Y.; King, B.; Wang, D.; Buhalis, D. In-destination tour products and the disrupted tourism industry: Progress and prospects. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2016, 16, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]