1. Introduction

The global spread of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which started in January 2020, had severe consequences on the economy and societies worldwide. A wide range of restrictions were introduced by governments to stop or at least limit the virus propagation. Some of them had exceptional effects on the functioning of business in almost every sector. Entrepreneurs faced a critical dilemma—to stop their activities or to adapt to the new reality. It is presumed that due to the pandemic major global economies will lose up to 4.5% of their gross domestic product (GDP) [

1]. According to the International Labor Organization, 8.8% of global working hours were lost in 2020 relative to the fourth quarter of 2019, which corresponds to 255 million full-time jobs [

2].

In the service sector, based on direct and face-to-face contact between the customer and staff, the limitations implied to restrain the virus were particularly heavy. Lockdowns imposed on societies suspended or highly limited the provision of such commercial services as travel, accommodation, food, health or recreation, causing a drop in sales and employment [

3]. One of the sectors that was severely affected by the restrictions related to COVID-19 pandemic was tourism, independently of the size or type of activity. The drop in demand has hit airlines, multi-national hotel chains and tour operators, as well as local travel agencies, guesthouses, souvenir sellers, tourist guides.

Since 1 January 2020, 30 countries of the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA) introduced non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to prevent the spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) responsible for the Coronavirus disease 2019 [

4]. The NPIs measures applied in the EU and EEA are divided into seven categories: physical distancing, hygiene and safety measures, case management and quarantine, ensuring treatment capacity, general measures, internal travel and international travel [

4]. Measures which can be identified as those that have affected tourism sector the most lie within physical distancing (i.e., stay-at home orders, restrictions on public gathering, closure of public spaces), hygiene and safety (i.e., use of protective masks), internal and international travel (restrictions related to travel and mobility, as well as closures of international land, air and maritime borders). Introduced gradually from 1 January 2020 the measures were temporarily or permanently lifted in the following months [

5]. The release of the COVID-19 vaccine and the availability of quick tests has contributed to some changes in the measures in force in the EU and EEA. In some countries consumption in restaurants indoors is limited for those customers possessing a vaccination certificate (i.e., in Italy); in others a digital certificate or negative test is required to access tourist establishments and local accommodation (i.e., Portugal) [

4].

The gravity of the crisis caused in the EU tourism industry by the spread of the Coronavirus is reflected in data related to accommodation occupancy and air transport. Between April 2020 and March 2021, compared with the preceding 12 months, the number of nights spent at EU tourist accommodation establishments dropped by 61%. Among the countries that were the most affected are those highly economically dependent on tourism, including Malta, Spain, Greece and Portugal [

6]. The RevPAR (Revenue Per Available Room) indicator of Accor-one of the largest hotel operators in the World, dropped globally from 67.6% in June 2019 to 33.5% in June 2021 [

7]. The number of passengers carried in air transport in EU countries dropped from 111,174,897 passengers in August 2019 to 30,597,275 passengers in August 2020 [

8]. The consequences of the pandemic have hit not just larger companies, but small-scale businesses and individual professionals as well.

One of the crucial professional groups involved in tourism business are tourist guides. They not only inform and educate tourists about the places being visited but serve also as a link to the local culture and society, enhancing a positive image of the destination. COVID-19 pandemic put this group of service providers all over the world in a very difficult professional situation. Lockdowns and social distancing regulations have urged prospective travelers to stay at home, individual and organized tourist trips have been cancelled or postponed.

According to the ESCO classification (European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations classification) tourist guides are included in a larger group of professionals called travel guides. Travel guides accompany individuals or groups on trips, sightseeing tours, and excursions and on tours of places of interest such as historical sites, industrial establishments, and theme parks. They describe points of interest and provide background information on interesting features [

9]. The European Federation of Tourist Guide Associations defines the tourist guide as a “person who guides visitors in the language of their choice and interprets the cultural and natural heritage of an area, which person normally possesses an area-specific qualification usually issued and/or recognized by the appropriate authority” [

10].

In the EU the work of tourist guides is considered as regulated professional services [

11]. Although the European Commission is encouraging member states to loosen regulations and restrictions regarding the profession of tourist guides [

12], a recent update on the state of regulation of professional services in the EU has shown that tourist guides are a profession still regulated in two thirds of the Member States [

11]. Tourist guides operate on the market primarily as self-employed persons running a sole proprietorship company. The method of formalizing the guide’s work depends on the legal regulations in force in this respect in the place of its operation. For example, in Spain, Italy and Croatia the exercise of tourist guide profession is regulated at regional level, guides may have to obtain different qualifications and authorizations within a single country if they want to provide services in more than one region [

11]. The performance of tourist guiding services in specific locations may be subject to additional requirements (holding of permits) which is the case in France and Croatia [

11]. Member States where the exercise of the tourist guide profession is not subject to any regulations are Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, The Netherlands and Sweden. In Poland only the mountain guides profession is regulated [

13].

The scale of formalizing the rules governing the functioning of guides in each destination may vary. According to Kronenberg and Szczecińska countries with more advanced federalism tend to cede the competencies regarding tourist guides profession to the regions while in centrally governed states the competences stay at the national level [

13]. According to Meged, compared to other fields of professions, guides have been institutionalized–and have institutionalized themselves–only to a small degree [

14]. Some formalization of the work of tourist guides, including in countries where there are no regulations for this profession, is done by non-governmental organizations by establishing guide associations at the local (city) or national level. Tourist guides associations primarily have an informative function, offering lists of licensed (if legally required) guides. They can also function as a certifying and training institution, often in collaboration with a city or country authority (i.e., British Guild of Tourist Guides). Tourist guides association can also perform a supportive role for their members by representing them (acting as brokers) on the market [

14].

The European Association of Tourist Guides Associations (FEG) in a survey involving 3000 qualified tourist guides indicated that the majority of them lost up to 80% of work in 2020. At the same time almost 50% was not able to access any financial support from governments (local or national) [

15]. The economic vulnerability of tourist guides is partially the result of their employment characteristic—87.8% of guides surveyed by FEG are self-employed [

16]. Sparse financial measures dedicated specially to tourist guides were adopted by governments, and they were perceived as very unsatisfactory [

17]. Some guides devoted time without work to improve their qualifications by learning new languages, working on marketing, or preparing themed guiding [

15]. Although it is difficult to acquire data regarding the percentage of tourist guides (worldwide or in the EU) who decided to change their occupation permanently or temporarily since the starting of COVID-19 pandemic, 80% of the professionals surveyed by FEG declare that they want to continue working as tourist guides.

Consequences of COVID-19 pandemic are reflected in research focused on the concept of sustainability and the sustainable development as those aspects are largely present in theoretical research and have practical implications as well. The most common definition of sustainability is the one provided by the Brundtland Commission, which defined it as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

18]. In a more detailed approach sustainability “deals with a balanced integration of social, environmental, and economic performance of human lives within the society, environment, and economy to the benefit of current and future generation” [

19].

A major study (covering 49 different research papers) was performed by Ranjbari et al. [

20] to present the state of research regarding COVID-19 and its influence on the economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development. The three main subject areas covered by research related to COVID-19 and sustainable development are healthcare, food industry and tourism [

20].

Jones and Comfort [

21] have analyzed the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on sustainability in the hospitality industry. They concluded that despite the temporary positive changes, i.e., in consumption patterns caused by COVID-19 crisis, new concepts of consumption and service production will not be introduced or accepted permanently. Göslling et al. [

22] have studied the implication of COVID-19 pandemic on the major sectors of the tourism industry: airlines, accommodation, events, restaurants and cruises. According to them “The COVID-19 pandemic should lead to a critical reconsideration of the global volume growth model for tourism, for interrelated reasons of risks incurred in global travel as well as the sector’s contribution to climate change” [

22] (p. 13).

In the face of such crisis as the one caused by COVID-19, the ability of entrepreneurs to react pro-actively by changing business models proved to be critical [

23]. Undoubtedly, the already existing IT-based tools and their new applications [

24] as well as innovative solutions [

25] have helped business owners to cope with challenges related to the downfall of supply. According to research by Obrenovic et al. [

26] it is easier for an enterprise to sustain business operations during pandemic if it adopts the rules of distributed leadership, workforce and an adaptive culture.

Research on the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship in general has focused mainly on innovation, resilience, knowledge, supply chains or tourism [

23]. In the process of analysis regarding the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on business two approaches are exposed: “COVID-19 as a facilitator of entrepreneurial activity (from a positive perspective) or COVID-19 as a burden on entrepreneurship (considering mainly its negative effects)” [

23]. The presented study fits in the first concept and aims at elucidating the positive consequences of the pandemic on entrepreneurial activity. The study follows an approach that the pandemic acted like ignition to create new business ventures, recognizing as well that there would be no positive consequences without other simultaneously appearing factors. The aim of the study is to provide additional insight and knowledge on how entrepreneurs, and specifically professionals like tourist guides deal with a crisis such as COVID-19 pandemic. To fulfill this goal the research presents a case study of an organization called Guides Without Borders (GWB) established in March 2020 and aims at exploring its business model and identify key success factors.

The paper is structured as follows. Theoretical background covers an overview of literature regarding sustainability and sustainable entrepreneurship in tourism (with the focus on tourist guides), the concept of social capital in relation to entrepreneurship activities and the main characteristics of teal organizations theory. Material and Methods section presents the method adapted for the study as well as the research questions and process followed by a description of the case being subject of the study. The paper continues with the Results and Discussion sections presenting the main findings of the research and their relation to previous studies. Conclusions reveal the practical and theoretical applications of the study as well as its limitations.

2. Theoretical Background

In general, it is possible to indicate two approaches to the term of entrepreneurship. The first relates only to the fact of creating new ventures, the second one is more complex, as it sees entrepreneurship as an attitude and mind-set that drives individuals [

27] and blends creativity and innovation with effective management [

28]. Entrepreneurship plays an important role in achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) introduced by the United Nations in the Agenda 2030 [

29]. Explicitly “entrepreneurship” appears only in two of the seventeen SDGs and it mentioned in the context of education and skills (SDG 4) and economic growth and employment (SDG 8) [

29]. However other goals present opportunities for entrepreneurs as well as the business sector is mentioned in the Agenda 2030 several times and its contribution to creative and innovative solving of sustainable development challenges in underlined in this document [

29]. When put in line with the sustainable development approach entrepreneurship is seen as a mean to achieve simultaneously social, economic and environmental goals and the sustainable entrepreneur is someone who introduces this approach in his or her organization [

30]. Sustainable entrepreneurship can be defined as “the examination of how opportunities to bring into existence “future” goods and services are discovered, created, and exploited, by whom, and with what economic, psychological, social and environmental consequence [

31] (p. 35). In the context of the complexity of nowadays business and business environment entrepreneurship is seen as “a dynamic process of vision, change and creation. It requires an application of energy and passion towards the creation and implementation of new value-adding ideas and creative solutions. Essential ingredients include the willingness to take calculated risks in terms of time, equity or career; the ability to formulate an effective venture team; the creative skill to marshal needed resources; and, finally, the vision to recognize opportunity where others see chaos, contradiction and confusion” [

32] (p. 11). This detailed definition of entrepreneurship in general combined with the specific character of sustainable entrepreneurship that underlines the foreseeing of social, economic and environmental consequences, is suitable to describe the characteristics of entrepreneurs who saw possibilities to create new ventures despite the COVID-19 related crisis.

Several researchers underline the need for more analysis on the traits of entrepreneurs that guarantee success during the COVID-19 crisis [

33]. Social processes and social interactions are important elements of entrepreneurship theory. According to [

34] entrepreneurship is a context dependent social process through which individuals and teams create wealth by bringing together unique packages of resources to exploit marketplace opportunities. It is more than obvious that entrepreneurial activities could not happen in isolation, and interaction between actors allows them to access resources, infrastructure, and knowledge [

32].

One of the most well-established theories explaining the importance of social relations in entrepreneurship is the theory of social capital. Nahapiet and Ghoshal, authors of a crucial research in the field of social capital and organizational performance define it as “the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or social unit” [

35] (p. 243). Key elements, that constitute the basis for social capital are connections between actors [

36], trust [

37] and the radius of trust [

38]. Another important element indicated as a foundation of social capital is civil engagement [

39] (i.e., membership in associations or electoral participation). The role of networks and ties is also in line with the entrepreneurial ecosystems concept (EE) [

40] in which the interconnections of elements (individuals or organizations) play a crucial role in its success and sustainability [

41], although it has been noticed that research on the relational dimension of the elements of an EEs are still scarce [

42]. Social capital is also recognized as the basis for sustainable local development. According to Selman “where stocks of social capital are buoyant and high levels of trust exist between individuals, favorable conditions exist for cooperation and participation in the pursuit of local sustainability” [

43] (p. 13) The importance of social ties and interactions in entrepreneurship seen as an opportunity to access a wide range of resources in times of crisis related to COVID-19 has been noticed by Ratten [

33]. For tourist guides the value of networks and professional relationships is of great importance. It translates into access to professional opportunities and development [

44], which can be more important in unfavorable conditions.

An additional element which can support the sustainable functioning of businesses is the application of digital tools. According to Chierici et al. [

45] the adoption of digital tools by small, innovative enterprises can support them in reaching for new opportunities as well as in improving existing business models. In view of the present study, it is important to notice, that sustainable competitive advantages of firms can be supported by digital tools in such manner that they enable access to “knowledge assets, competences and complementary assets and technologies” [

45] (p. 624).

In the social aspect, the sustainable dimension of the tourist guide profession lies in the interpretative or mediatory function the guide performs. The interaction of tourists with local community, cultural heritage and environment is enhanced by the tourist guide. Tourist guides are considered interpreters of tangible and intangible heritage. Their role as mediators or brokers between the host community and the visitors has been the subject of substantial research [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Hu and Wall have undertaken detailed research of the relationship between tour guides work and sustainability, concentrating on the interpretative aspect [

50]. In their opinion, tour guides are involved in almost all the tourism industry and its stakeholders [

50]. It is possible to indicate the following areas of interaction of the tourist guide with the tourism sector: “the tourists, the destination resources, the local communities, the employer, the governmental authorities and the guides themselves” [

50] (p. 80). Drawing on the mentioned areas of interaction Hu and Wall have shown the relationship between tourist guides professional work and the respective spheres of sustainable development. Their research indicates that tour guides perform three different functions in which they promote sustainability. The first function relates to experience management (with a focus on tourists) where the responsibility of the tour guide lies i.e., in fostering positive host-guest encounters. The second function refers to resources management (with a focus on places visited) where the tour guide is responsible mainly for encouraging guests to appreciate the visited places and to support responsible behaviors in the long-term. The third function lies in the promotion of local economies (with a focus on local communities) by inciting tourists to buy local products and services [

50]. The performance of above-mentioned functions is possible if the local guides maintain a detailed knowledge of the areas visited with tourists [

51] and a close relationship with the place [

52] and host communities.

Information technology (IT), defined as the study or use of systems (especially computers and telecommunications) for storing, retrieving, and sending information [

53] can support the exercise of tourist guides duties in different aspects. It can help in the acquisition of knew knowledge, provide a better accessibility to potential clients (promotion on the Internet) or boost the visiting experience as well as make it more accessible (i.e., serving as audio device). An interesting overview of the possibilities provided by new technologies in tourism guiding has been prepared by de la Harpe and Sevenhuysen [

54]. It is important to notice as well that the spread of IT in the tourism sector, especially on the demand side (use of IT by tourists) can pose some challenges to the tourist guides. Tourists acquire detailed knowledge about the destination from the Internet even before they arrive on site, they have the possibility to use guiding aps on their smartphones and thus may decide they don’t need to take part in guided tours [

54]. Tourist guides are part of the demand side of the tourism industry and tourism market. As mentioned earlier, professional tourist guides exercise their services as sole-proprietorship companies thus being considered as small tourism enterprises [

55]. They deliver services either directly to individual tourists or to organized groups usually through the intermediary of a tour organizer. Research has already been undertaken to investigate the relationships between different entrepreneurial characteristics and the ability to cope with such crisis like COVID-19 pandemic [

33,

56]. At this moment it is too early to say which business model or strategy has greater potential for success. Times of uncertainty and crisis are potentially attractive to researchers studying and testing the effectiveness of different business solutions [

57].

One possible modern approach to organizational management is the teal and self-governed model described by Frederic Laloux in his book “Reinventing Organizations” [

58]. According to Laloux [

58] an organization adopting the organic type of structure and business activities has among others, the following characteristics:

Lack of typical management board, individual employees perform all the tasks necessary for the functioning of the company by dividing them among themselves

There are no staff positions, an external expert may appear as a last resort, but only for the duration of the problem resolution. Trainings allow employees to solve difficulties and acquire the necessary competences, who then share their knowledge with others (which also serves to increase employees′ self-confidence)

Reverse delegation-solutions and tasks are not imposed in advance, unless the team, makes such a decision in a situation where it cannot find a solution

Giving up the economy of scale in favor of unbridled motivation, it is the motivation of individual employees that drives the company

Self-realization hierarchy (recognition, influence, skills)

The structure follows emerging problems and not the other way around (if necessary, ad hoc meetings are organized)

Use of self-governance

The use of IT technologies in order to avoid introducing unnecessary structures (i.e., to exchange knowledge on the intranet forum)

Utilizing and building employees’ trust in each other and in management

“Collective system intelligence” enforces a natural way of implementing projects, there is no need to create artificial structures.

The mode of organization proposed by Laloux can be helpful to overcome external (and internal) difficulties. Previous studies on its supporting role include, i.e., improvement of information flow [

59], increase of autonomy in decision making [

60] or more effective functioning of collaborative platforms [

61].

Even though research on tourist guides has made a significant development in the last 10–15 years [

62], there are still many areas and theories insufficiently researched scientifically (especially empirically) in the context of this important tourism profession. The areas that still require further research are i.e., geography, environmental science, economics, sociology, communications, political science, policy studies, planning, education, and business studies including consumer behavior, marketing and management [

61].

3. Materials and Methods

The research is based on the case study method (CS) understood as an empirical study that is concentrated on understanding a contemporary phenomenon (case) in its real context, where the limits between the case and the context are hard to define [

63]. The case study is one of the methods used in qualitative research [

64] appreciated in many scientific disciplines, including social sciences and economy. It may be used to empirically highlight some theoretic notions or rules. Case studies are used for explanation, description, or exploration of contemporary phenomena. In general, the case study method (or strategy) is appropriate in every research situation where the main questions to ask are “how?” and “why?” and when the research relates to a set of contemporary data on which the researcher has no influence [

63].

Examples of CS implementation in research on entrepreneurship include, i.e., value creation in e-business [

65], social entrepreneurship and woman empowerment [

66], entrepreneurial ecosystems [

67], innovation in technology parks [

68], the adoption of new organizational forms [

58,

69]. This method is also applied in tourism research i.e., to investigate overtourism [

70], motivation and satisfaction of event attendees [

71], bicycle tourism [

72], the meaning of borders [

73]. Examples of case studies regarding tourist guides concentrate, i.e., on education and training [

74,

75], mobile applications [

76,

77] or professional and personal aspects of tourist guiding [

52,

78] and organizational culture [

79]. The cognitive possibilities offered by the CS method encourage to use it for gathering detailed knowledge on the process of starting and functioning of a tourist guides organization in times of crisis. For the purpose of this research, an organization called Guides Without Borders (GWB) has been selected. One of the reasons to choose the case study as a research method is to explain an exceptional phenomenon [

63]. The exceptionality of the chosen organization and thus the reasons that incline to treat it as a case worth studying is based on the following traits: (i) GWB was initiated during the COVID-19 pandemic—an unprecedented context for business creation, as a consequence (ii) the use of IT and digital devices played a singular role in the process of developing this venture and providing its services, (iii) GWB introduced a new form of tourist guides professional cooperation on the tourism market.

To the best knowledge of the author of the presented research, no other organization of such type as GWB has been initiated in the EU in the first starting months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The following research questions are addressed in this study:

Why was it possible to start GWB despite the crisis caused by COVID-19 pandemic?

How does the organizational structure and process applied in this venture work, do they correspond to the concept of teal organizations?

What is the role of social ties and interactions in the functioning of GWB?

Although the research applies a case study approach it is composed of mixed methods in such a way, that the mixed methods are nested in the case study [

63] and they help in acquiring a more complex image of the case. As proposed by Plano Clark and Ivankova [

80] (p. 2) mixed methods research is “a process of research in which researchers integrate quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection and analysis to best understand a research purpose. The way this process unfolds in a given study is shaped by mixed methods research content considerations and researchers’ personal, interpersonal, and social contexts”. An approach that uses mixed methods to improve the complex purposes of a single study is widely accepted and used in research [

80].

The research was based on qualitative data and had a descriptive character. Its main purpose was to get in-depth knowledge on the functioning of GWB organization, namely, to assess its business model and to point-out the traits of tourists guides involved in the project, in a way to answer the research questions. The research was performed in 4 stages. Stages 1 to 3 led to the gathering of holistic information about the organization, stage 4 aimed at acquiring data on the units nested in the case—namely the individual tourist guides involved in the organization. Stage 1 consisted of literature review on the subject (to prepare a general background for the research) and on gathering information on the studied organization from secondary sources (the website of the organization and its social media pages; mentions of the organization in Internet-based media i.e., radio stations). Stage 2 consisted of several on-line, group and individual meetings with the leaders and members of the organization: 1 group meeting with all the leaders (4 participants); 1 general meeting with the leaders and several members of the organization (to make observations about the group). Stage 3 involved individual meetings with 3 leaders during which structured interviews were performed. During stage 4 an online questionnaire was addressed to all members of GWB. The population size for the questionnaire was 50, a confidence level of 95% was adapted and the confidence interval was of 13.45, as a result a sample size of 26 questionnaires was determined as the required number of respondents (this condition has been met by the research).

The discussion and the interviews (stages 2 and 3) were performed via videotelephone through a peer-to-peer software. For stage 3 of a series of 12 questions was send to the interviewees prior to the interviews (

Table 1). Each interviewed person addressed previously chosen questions. The time lapse between sending the questions and performing the interviews was of 20 days. Before starting the interviews, each participant was asked to consent to audio registration of the meeting (for transcription purposes). The questions were elaborated especially for the purpose of the research, based on the review of literature and information about GWB from secondary sources (stage 1) as well as on the general information acquired during the online meetings (stage 2).

As stated earlier, stage 4 of the research consisted of an online questionnaire (performed with the use of Google Forms) dedicated to the guides, members of the organization. The questionnaire was open for responses between 24 June 2021 and 24 July 2021, a link to the online questionnaire was sent to the guides by the leader of GWB. A total of 26 properly filled questionnaires was registered [

81]. The software used for online questioning guaranteed anonymity of the respondents. The questionnaire was composed of 19 close-ended questions. A multiple-choice option was possible for 2 questions. In 9 questions a 5-point Likert scale was applied. The respondents were informed that participation in the research was voluntary and anonymous and that the results would be used for scientific purposes.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristic of Guides without Borders Organization

The object of the presented case study is a company called Guides without Borders (GWB). The starting point for this venture was the COVID-19 lockdown and the travel restrictions that followed. The organization has been initiated in March 2020 by four guides of Polish origin residing in Spain and Portugal. The Polish background of this initiative plays an important role in its business model. The products are offered on the Polish market and the concept concentrates on an idea to sell the services of Polish tour guides to Polish tourists (in Polish). With the starting of COVID-19 pandemic and a perspective of losing their jobs due to the absence of individual tourists or groups onsite, the guides prepared videos of attractions accompanied by narratives and practical information. The videos could be purchased and watched from any place in the world via Facebook.

As of October 2021, the organization (in Polish Przewodnicy Bez Granic) gathers 54 tourist guides from 27 countries, including 34 guides from 13 EU member countries and 20 guides from 14 non-EU countries (the number of tourist guides involved in GWB is not constant) [

82]. The main product offered by GWB is live, on-line walking tours organized on a weekly basis, from different places in the World, accessible for a limited number of viewers. Another service in the offer of GWB are on-line, on-demand sightseeing or “Walks with a guide” ordered individually. There is also a possibility of off-line (traditional) sightseeing in the situation where COVID-19 restrictions are not in force. Additionally, the organization has in its offer a culinary e-book as well as a service that consists of sending postcards from a chosen city to the person indicated by the client. Marketing and promotion of the organization itself and the offered services is performed through a dedicated website, YouTube platform and social networks (Facebook: Menlo Park, CA, USA; Instagram: Menlo Park, CA, USA).

Guides Without Borders organization grew from a handful of members in 2020 to over 50 guides in 2021. The growing interest in the GWB offer is illustrated by the number of participants in virtual walks broadcasted live via Facebook, which increased on average from about 8 people in September 2020 to about 600 in March 2021.The pricing strategy for products offered by GWB is demand-based. The first online sightseeing was sold at a symbolic price of EUR 1. For promotion purposes this price was referred to as “one coffee for the guide”. Over time, with growing popularity of the products the price rose to approx. EUR 5.5.

GWB call their organizational structure as organic. It is an open, informal structure that gives members freedom as to the degree of involvement in the project. The leaders of the organization and its founders, in the number of 4 people, form the so-called Initiative Group (they have known each other for several years and have already had the opportunity to cooperate in serving individual tourists and groups visiting Barcelona).

The guides meet online, once a week to discuss current affairs, future activities, and projects. These meetings are also an opportunity to share ideas for new products or to improve the offer. Each guide has the right to propose his own idea. Ideas are voted on and 5 are selected for implementation. The person who is the author of the project is designated as responsible for its implementation. After discussing the details and deciding about the implementation of a given project, the so-called Ministry is formed in which the initiator of the idea is the Minister. This unit involves as well approx. 4 other people willing to co-create the project and one representative of the Initiative Group. All members of the Ministry are selected according to the knowledge and skills needed to implement the project, as well as in terms of personality. Another element of the GWB organizational structure is the so-called Senate, which plays a role analogue to staff groups in a traditionally organized firm. The Senate is formed by 12 guides who act as mentors or coaches, providing emotional support and motivation for other members. The organizational structure adopted in GWB is of flat (or parallel) type.

4.2. Tourist Guides, Members of the Organization

This section of the paper presents the study results in a mixed manner, including in a major part data obtained from questionnaires as well as information gathered during the structured interviews. Presented results refer to social relations in force in the organization, to the use IT and to the benefits of participating in GWB as well as to the organization of GWBs’ work.

In the opinion of the Initiative Group, the activity of GWB is based on unlimited commitment, a sense of belonging, friendship, and trust. Random guides are not accepted into the GWB group. The recruitment process is based on recommendation (by members of GWB, trusted guides or clients) and emotion. The research indicates that 61.5% of respondents knew a member of GWB before joining the organization, 53.8% were contacted by the GWB with an offer of cooperation.

As stated by the leaders of GWB the initiative started not only because of the consequences of COVID-19 related restrictions, but also as a result of a lasting reflection regarding the state of tourist guides profession. In their opinion tourist guides (especially those working in the same city) have difficulties to cooperate effectively with each other or even tend to avoid cooperation fearing that it could lead to a loss of customers (it is important to indicate that this remark referred to guides of Polish nationality or origin). When replying to a question regarding the benefits of the GWB project the leaders answered that the social benefits of the project as a network of guides, were the most important. In their opinion creating groups of professionals for better cooperation is a prerequisite for business success. A sense of “togetherness”, of being “a big family” or a “tribe” has been indicated as the principal value.

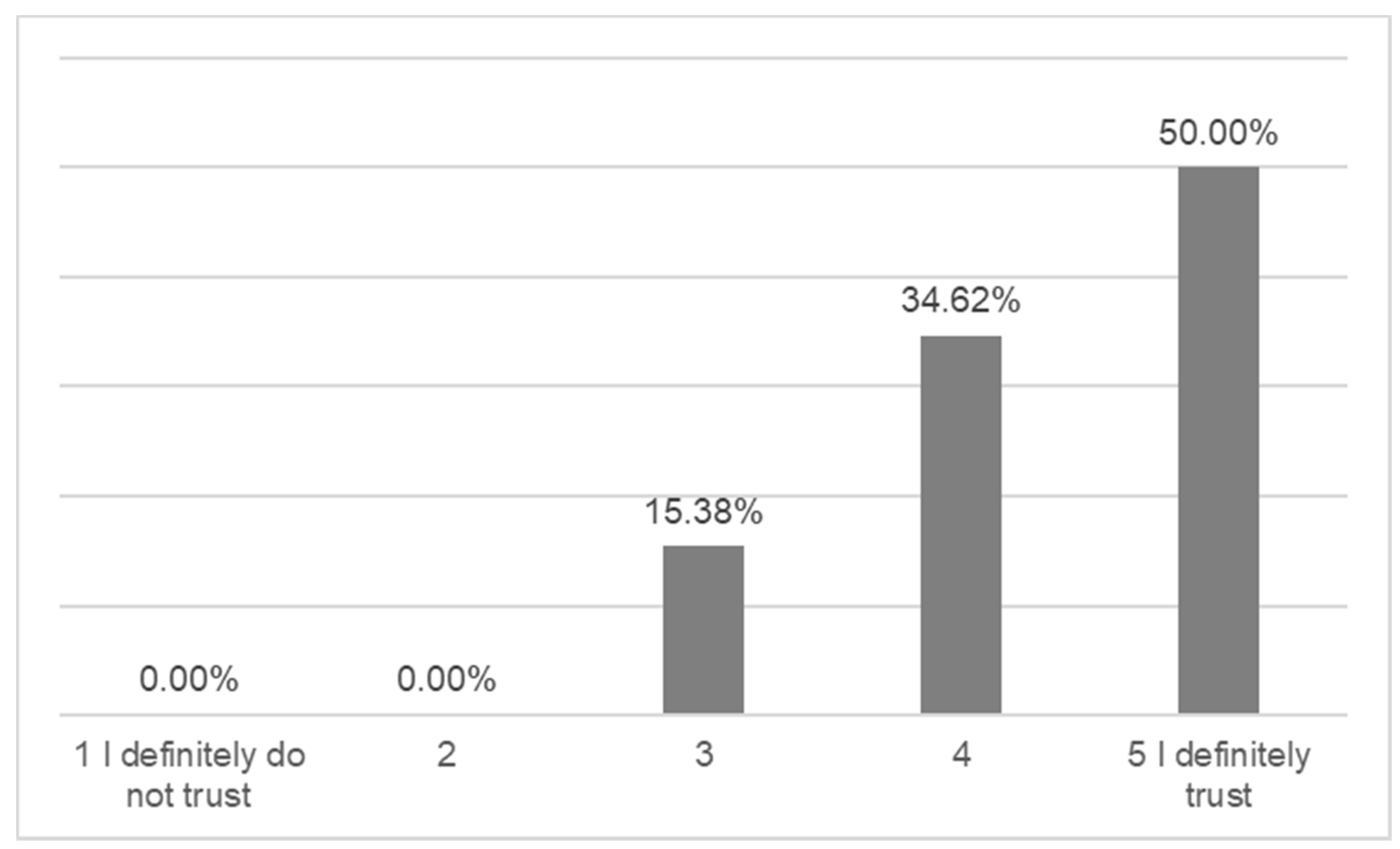

Mutual relations between members play an important role in the analyzed organization. 57.69% of respondents strongly identify with other members of GWB. The degree of trust between members is also high. 50% of the respondents definitely trust other guides from the group (excluding the Initiative Group) (

Figure 1), while 57.69% of the respondents express their trust in the leaders (Initiative Group). It is important to notice that 57.9% of GWB members define themselves as persons trusting others.

An important aspect shaping the activities of GWB is mutual support, even in situations not related to the activities within the organization (50% of respondents believe that they can definitely count on such support). GWB members have experience in being active in various types of associations. While 50% of the respondents had not been associated with this type of organizations in the past, 42.3% are linked to other organizations and 7.7% had a history of participating in initiatives like GWB.

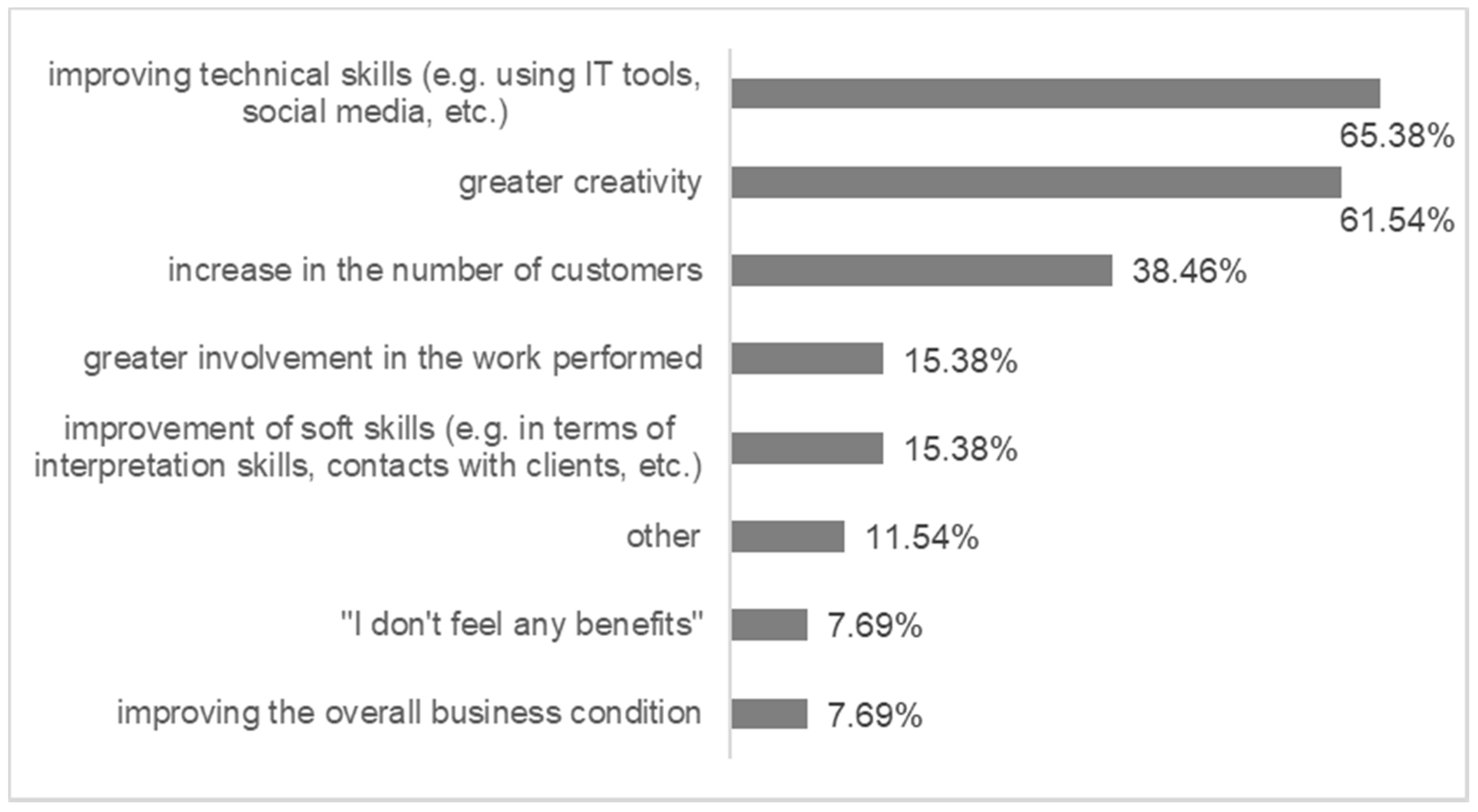

GWB leaders underline that a large part of tourist guides involved in the project had very limited or no previous experience with IT tools and digital technologies. The initiative led to a dissemination of knowledge among participants, who shared their insight on: IT tools (video, multimedia), social media (content introduction and management), digital equipment (microphone, gimbal, smartphone).

Dissemination of knowledge was organized in the form of short courses or chats, led by members of GWB considered as experts in a given field. Only after a visible development of the GWB initiative the leaders considered to invite external professionals to provide new knowledge to the network. The improvement of technical proficiency is the most important benefit of GWB participation indicated by its members (

Figure 2). Although some of the respondents do not see an improvement in their overall business condition it is important to notice that an increase in the number of customers holds the third position among the indicated benefits. Answers indicated in the chart as “other” benefits included the following statements: making friends, well-being and therapy in a difficult time, verification of colleagues from the industry in each destination. For 46.2% of the respondents the benefits increase with time and 53.8% of them are definitely satisfied of taking part in GWB.

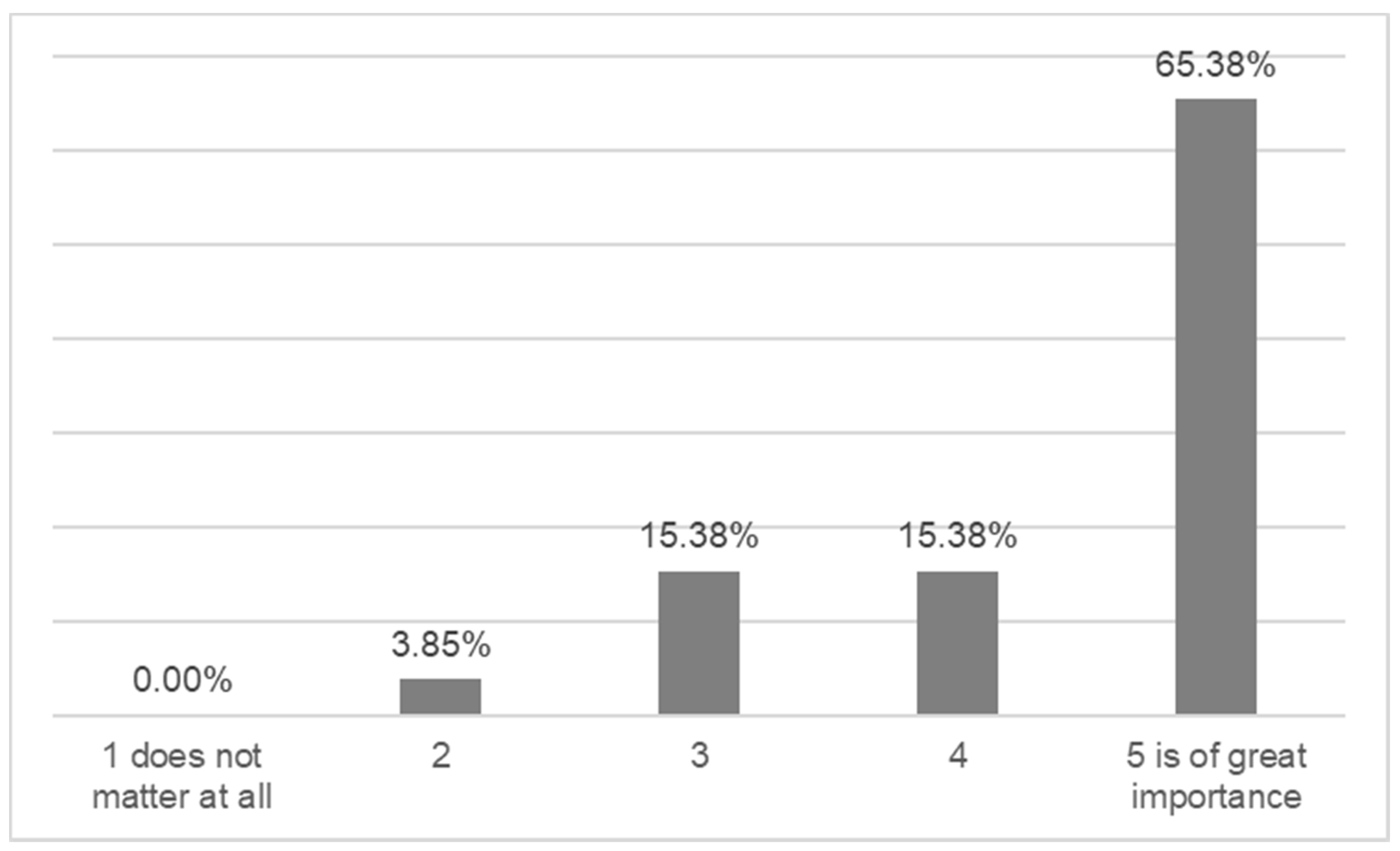

Cost-free work, or volunteer work plays an important part in the organization. Members are invited to use their skills to improve the performance of GWB. Specialized knowledge is used to write social media content, graphic design (i.e., the project logo and visual identification). Some forms of unpaid work are obligatory, including writing blog posts or involvement in promotion activities. For the guides surveyed, non-financial recognition of the performed work, such as praise or recommendations, is of great importance (

Figure 3). This can be the basis of their involvement in voluntary work.

Technology plays an important role in the day-to-day functioning of GWB. In the opinion of the Initiative Group, it has been one of the key driving elements from the starting point. The entire communication process is based on peer-to-peer technology. As the organization formed when the COVID-19 pandemic was at its highest level and the restrictions were the heaviest, only online communication between the guides was possible. In addition, the location of the guides in different parts of the world forced the application of such strategy.

In the situation of GWB the use online communication platforms as primary channels of cooperation dictated the mode of organization. It had also influence on the relationships and bonds that formed within GWB. During the interviews, the members of the Initiative Group underlined that contact facilitated by online communication platforms led to the creation of strong ties between the guides, which in turn positively affected the effectiveness and quality of business activities undertaken within GWB. Two questions in the survey addressed the issue of formal and informal contacts between the members of GWB. 42.3% of the surveyed guides had formal contacts few times a week, 34.6% few times per month and 7.7% every day. The informal contacts happen correspondingly few times a week for 34.6%, followed by 30.8% and 15.4%.

5. Discussion

Laloux [

58] (pp. 385–389) identified over 30 areas in which self-organized (teal) organizations differ from traditional ones, divided in such aspects of organization as: structure, human resources, everyday life, and main organizational processes. This list will be applied to point-out the main characteristics of Guides without Borders gathered through the research and to answer the research questions posed in this study.

The organizational structure of GWB follows a scheme of self-organized teams (parallel teams according to Laloux study) concentrated on the performance of one specific project or task, i.e., the culinary e-book, a book with tales for children or the webpage. Although the Initiative Group (the leaders) meet regularly, other meetings are organized ad-hoc, depending on the needs. One meeting happens regularly, once a week, but its purpose is not only professional, it is rather an occasion for small-talk and some updates on current achievements. The coordination of tasks is left to the responsible teams, who are bottom-up formed—whenever someone feels he is fit to join a project it is up to him to contact the relevant team. This approach to the distribution of tasks reflects the trust that leaders have in the guides as well as the confidence between the guides themselves. As indicated by Fukuyama [

38] (p. 7) “social capital is an instantiated informal norm that promotes co-operation between two or more individuals”. This leads to a conclusion that social capital plays an important part in the organizational success of this venture. In contrast to traditional forms of tourist guides organizations GWB does not function like a registry of tourist guides, but like a platform for cooperation and for achieving goals which are common for all guides in the organization. It is an informal network adjusted to realize business goals.

Another important point that stands out in the organizational processes applied in GWB is the absence of staff functions. If there is a need for acquiring new knowledge other members of GWB are the first option. This type of solution for skills improvement among employees has been indicated by Laloux [

58] as a characteristic of teal organizations. External support is introduced only in the case when high specialization skills are required, i.e., a specialist in search engines optimization. In case of any difficulties, the guides can count on each other, seeking help from the Senate or the Initiative Group.

In the area of human resources GWB follow a very strict process when recruiting new guides. There are no job advertisements, only guides in the network of contacts of the Initiative Group or other guides already involved in GWB can participate in the recruitment process. New skills that a person can bring to the organization play an important role, but equally important is the quality of the contact with a future GWB member, the mood that accompanies the conversation. There are no job descriptions, no assigned roles or job titles. Working hours are not recorded, the degree of commitment is arbitrary, but organization members are aware that a failure to meet obligations has consequences not only for the IG, but also for other team members and the entire organization. Joint determination of projects and tasks increases the sense of responsibility. The differentiation in remuneration results from the degree of involvement in each project. The project initiator gets more if the project is successful. Profit is shared as revenues arise.

Redundancies happen very rarely, so far only once was it necessary to terminate the cooperation with one of the guides. If there are any difficulties, the first instance is to talk and try to solve the problem together. The organization does not have a specific promotion path, roles change, guides are encouraged to point out errors or observed shortcomings in the implementation of joint activities.

Since GWB operates in the virtual space, it is difficult to indicate rules applicable to everyday life of this organization. The observation of GWB meetings and their relations on the Internet, leads to a conclusion that they feel good about showing their everyday, even informal space. The lack of formalization also applies to the outfit of guides. They approach this aspect in a humorous manner, often dressing up as various characters related to the history of a given place or staging scenes that diversify the message.

Despite the restrictions related to COVID-19 pandemic and the distance between them, the guides managed to build a community. Its functioning can be compared to a diaspora (in this case, the Polish origin of guides plays a role). The key values on which the activity of GWB is based are friendship, trust, “faith in the power brought by knowledge and sharing it” (statement of one of the leaders), as well as an optimistic and open attitude towards the environment. Common norms and values as well as “shared representations, interpretations, and systems of meaning among parties” [

35] (p. 244) are one of the dimensions of social capital and an additional resource of the organization in question.

The Initiative Group emphasizes that there is no competition among the guides working at GWB. This is due, on the one hand, to the fact that they work in various places around the world, but also to the fact that the ties that bind them are based on the values mentioned above. This characteristic is in opposition to one of the findings of Ghahramani et al. [

44] that discovered a link between poor performance and disconnectedness among tour guides, and an absence of communication networks, mechanisms for networking and knowledge sharing. One of the elements that helped the guides to connect was wide application of communication technologies. Social ties within an organization can be improved through integration of Internet and Communication Technology (ICT) in daily routines during and post crisis [

26]. The integration of ICT, Intranet, social media, and online communication platforms in daily routines is a characteristic of prosperous organizations [

26]. For GWB the widespread adoption, familiarity with and popularity of peer-to-peer communication platforms has led to tightening of professional and personal ties.

A recently emerged, new aspect in research on entrepreneurship among guides is the relationship between licensed and experienced guides with a new phenomenon emerging on the basis of the sharing economy and the tourist guides profession regulation withdrawal, namely free guided tours. Free guides operate from online platforms, their income is variable and based on tips [

83]. Although the presented research did not bring up the problem of free guides, members of the Initiative Group were asked about the existence of similar organizations. In this aspect GWB are aware of the possible emergence of businesses that could imitate their way of operating.

In relation to the main organizational processes, in the area of strategy, the organization has only a general framework for action, individual areas of action appear as new opportunities emerge, contacts occur, and ideas are adopted by new members of the organization. As in the description of the teal organization presented by Laloux, the guides working at GWB form a “collective intelligence” from which new concepts emerge. Marketing conducted by GWB can be defined as conveying ideas from the inside out—GWB mission and the beliefs of the guides are the most important, they strictly adhere to the concept of their market proposition and believe in the value of the offered set of products. GWB is not guided by the preferences of specific audience segments, but at the same time it communicates very intensively with them.

The approach of GWB towards sustainability is positive. The leaders are aware of the fact that as tourist guides, they have the potential to change the aptitudes of their clients towards the environment, local society and economy. One of the main aspects of their work in this regard is reflected in the way they organize the tours when not operating online. They visit shops that offer products of local provenance and small restaurants. Although not covering all dimensions of a sustainable approach to tourism organization (i.e., transport and accommodation measures which are often located outside the sphere of influence of the tourist guides) this approach can be seen as advantage in supporting local economy and enabling tourists to come into contact with local communities [

51].

6. Conclusions

The study investigated a tourist guide venture initiated in the uncertain times of the tourism industry crisis caused by COVID-19 pandemic. The main purpose of the research was to examine which conditions have contributed to the success of this initiative and do they support previous findings related to the theory of teal organizations and social capital. Additionally, it was of interest to identify how IT and digital tools can have a supportive role in performing professional activities of tourist guides and in helping to build the studied organization.

Although not all of teal organization aspects studied by Laloux [

58] could be investigated or explained in the presented research, which is certainly one of its limitations, it was possible to draw out several interesting observations that allow to understand the way Guides without Borders operates.

A principal finding of the research indicates that though formally registered as a business, the group functions rather like an association composed of members supporting its activities than a formal structure of subordinated staff. Such an informal approach to the organization of the business structure and the daily professional routines of the members allowed for an agile adaptation to the new reality caused by COVID-19 related restrictions. This finding confirms previous statements, identified by Romero et al. that adopting an organic structure (a teal organization model) based on self-management facilitates the functioning of an enterprise in complicated environments [

61]. The gathering in one place of people with similar devotion to their work and passion for knowledge sharing and, additionally forming a group characterized by trust and friendship helped to build a flat organizational structure. The exact level of social capital of the tourist guides involved in GWB was not evaluated; nonetheless, it is possible to indicate that the mutual trust they show could facilitate effective cooperation.

The sustainability of the business model adapted by GWB has not been studied in this paper. Only one question related to sustainability was asked in the structured interviews. Considering that sustainable entrepreneurship can be understood as a contribution of the business to the fulfillment of the SDGs it is possible to draw the following conclusions. The business model adapted by GWB is following the assumptions of sustainable entrepreneurship in terms of the exercise of the guides day to day work as being supportive for the local economy. If the method of online sightseeing gains further popularity (several guides declare that they are willing to continue this type of service even after the pandemic) this could support the reduction of individual travels for tourist purposes. The online walking tours offered by GWB are watched by disabled people thus making the “visited” places more accessible.

From the practical point of view, the research shows that restriction measures such as those imposed due to the spread of Coronavirus are not necessarily a limitation to the creation of new businesses. The wise use and adoption of IT and digital devices and the possibilities they offer to create new, innovative services provide new opportunities for business evolution. GWB used only the basic achievements of digital technology, already widely applied in everyday practice. This remark indicates that there is possibility to develop especially designed technology that could help the guides in performing online sightseeing tours.

The principal limitation of the research lies in the fact that it is a single-case study, and the sample of respondents (tourist guides) was small and purposefully selected, thus the results and conclusions drawn cannot be extrapolated to the larger community of all tourist guides in the EU or in the world. Nonetheless, explanations drawn from the case study are an attempt to fill in the gap in literature regarding the profession of tourist guides and its main purpose was to explain the functioning of one exceptional organization. The study can serve as a source of inspiration for future business ventures that would like to introduce an organic approach to their organization.