Abstract

Benin is one of Africa’s leading authorities in cotton production. Today, Benin’s textile firms face challenges that affect their textile production efficiency level. The study employs exploratory and descriptive methods. Applying the AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) methods to make proper analysis after a wide range of surveys to provide guidance about the resilience of the textile industry in Benin. The SWOT-AHP approach was employed with secondary data sources. The analytical results highlight the need for private capital to resolve technical challenges and boost the industry’s competitiveness by examining the manufactory’s significant weaknesses, such as dated technological installations and the implementation of source energy. Overall, the results suggest that Benin state plays a regulatory role rather than a decision-making role. For the country’s textile firms to benefit economically and enhance their efficiency level, we recommend that Benin’s government switch the industrial structure from cotton processing to textile manufacturing. Moreover, the results obtained also testify that, on the one hand, there is a need to rebuild the foundations of industrial development in order to link industrial sectors with the potential of the primary and tertiary sectors, and on the other hand, it is important to set up an adequate environment that is capable of allowing industrial activity to be carried out effectively, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs, hence enhancing the sustainability of Benin textile companies’ performance.

1. Introduction

The cotton industry is fundamental to the development of global capitalism and broadly shapes the world we live in today [1] Cotton is considered one of Africa’s leading exports in the textile industry. According to [2], Africa’s global production contributes about 8% of total crop production. Crop cultivation is predominantly concentrated in the continent’s Western region and, more specifically, in former French colonies. These countries include Mali, Burkina-Faso, Benin, Ivory Coast, and Senegal, as top producers in the area. In the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) region, specifically in Benin, crop serves as an engine for economic growth, providing an income source for nearly 15 million people. Benin’s exportation relies on cotton production [3], and the country became the top cotton producer during the 2019–2020 season [4], allowing a 35% global GDP growth, a 13% agricultural GDP, and about a 45% increase in rural employment and income rate. These statistics show how the conversion of cotton into textiles exhibits potential in the cotton-textile sector’s economic growth. According to [5], cotton remains fundamental to the West and Central African regions. Ref. [6] argues that local textile firms are Benin’s second most important job creators, with over 46 functioning spinning mills installed in the WAEMU region since 2003. These include 18 ginning plants, three textile units, three cottonseed grinding units, and a cotton spinning mill. Over 10 of these mills currently operate at maximum capacities, processing about 2% of the cotton fiber [6]. Despite the gains made, it is noteworthy that the sector is underdeveloped and poorly managed in its processing chain.

One of the harmful effects of the state’s monopoly system was the appointment of incompetent managers as the head of these companies [7]. This encouraged lax management and bad governance by favoring these individuals’ particular interests, to the textile sector’s detriment. This has impeded the transformation of Benin’s cotton into unbleached, printed fabrics and clothing. This mismanagement led to the closure of several textile factories in the country. One of these is the Textile Complex of Benin (COTEB), an integrated factory that processes cotton fiber into ready-to-wear products. The company produces military and paramilitary outfits, school outfits, work clothes, household linen, sponge items, towels, bath sheets, bathrobes, and baby key chains, etc. While cotton production has increased in recent years, the processing sector has remained stagnant, which has affected the industry’s export potential. The Ministry of Industry of Benin recently published several findings highlighting the unbleached and printed fabric industry crisis. For example, [7] illustrated in its work about textile industry development in Benin by using the case of complex textile of Benin (COTEB). These challenges are also common for the Society of Textile Industries (SITEX) and the Beninese Textile Company (CBT), which are going through a crisis characterized by a decrease in production, with a significant drop in exports that have significantly reduced earnings for both institutions. These misfortunes follow a series of restructuring and business recovery attempts by the Board of Directors, which were approved by the Council of Ministers of the Beninese Government in February 2015.

The concept of sustainable development is long known and recognized as important. According to [8], the most famous definition of sustainable development is given in the 1987 Brundtland Report: “as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Unfortunately, according to [9], the concept is not always clearly defined. A variety of definitions and meanings of sustainability are possible. Sustainable production is important to efficiently use our resources and reduce waste and related costs [10]. Generally, according to [11], there are three pillars of sustainability (social, economic, and environmental), with the famous three circles diagram illustration to have been first presented by Barbier [12], albeit purposed towards developing nations. Increasingly, sustainability is being adopted as a desirable goal by policy-makers at both international and national levels. While focusing on two sustainability pillars (economic and social) for this research, we will conduct a diagnostic of these companies to understand and explore the factors influencing their development by applying the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) technique in combination with the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Following a concise review of previous studies, such as [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], our investigation underlines investment arrangements through sustainable development opportunities to increase gross domestic product. We argue that the state could justify its intervention by providing subsidies for maintaining the functionality of these production units. Furthermore, this study provides empirical evidence of the challenges highlighted, underlining the need to enhance Benin’s economic future. The findings are subjected to a rigorous review of publications and national policies. Therefore, the contribution of this current research is manifold. It will specifically assist start-up manufacturing businesses in determining which strategy companies should pursue to solve manufacturing issues. Long-established manufacturing companies may want to reconsider their existing approach in light of the finding of this study. Furthermore, government and social organizations can learn from this finding to improve their approach on how to deal with the management of the textile sector, while enhancing sustainable development.

Given the importance of the cotton-textile sector to Benin’s economy, and for all the actors involved, it is imperative to conduct research and offer recommendations to enrich the development of the industry. As this study aims to bridge the gap between textile companies and government involvement in the cotton-textile sector, by evaluating the critical factors and exploring how Benin’s textile industries deal with the challenges they face, we focused on three variables to understand it, as follows. (1) Managerial factors influencing the performance of textile productivity (independent variable). (2) Decision-making and productivity (dependent variable). (3) SWOT/AHP analysis mediating the relationship between (1) and (2). The findings from testing these variables through each group and priority (SWOT/AHP) will feed into the existing literature and help policy-makers implement effective strategies for the sustainable development of this sector. Too much investment in Benin and the sub-region can be the foundation for future research, together with decision-making support for government and companies to aid the country’s economic value. While the first section discusses the relevant works of literature, the next section will detail the methodology and data. The final section will conclude with socio-economic policy implications.

2. Literature Review

Overview of Cotton Textile

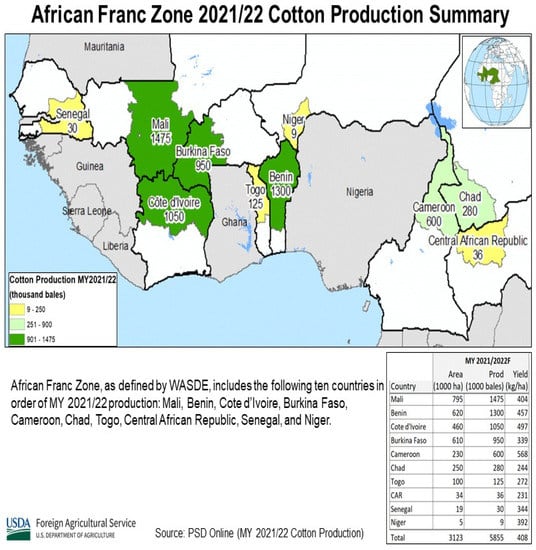

Since the 1960s, world cotton production has doubled from 10.2 to 20.3 million tons, corresponding to a likely annual increase of 1.7% [14]. This has garnered the cash crop as an integral part of the livelihoods of many countries, such as China. In the 2018–2019 harvest season, they became the world’s largest producer of 6 million tons, followed by India and the United States of America, with 5.8 and 4.0 million tons, respectively. Before the 1960s, cotton production in Africa was concentrated in Egypt, Tanzania, Uganda, Sudan, and Zimbabwe [15,16]. During the colonial regimes, the crop quickly became a source of income for over 15 African countries [17], contributing to poverty reductions [18,19]. With the coming of the French, much of the production concentration shifted to the western tip of the continent. Today, total cotton export contributes between 25% and 45% of West Africa’s GDP [20]. The crop contributes between 3% and 10% of the GDP of the top four producers in Africa (Benin, Burkina- Faso, Mali, and Chad). According to [21], in the 2019–2020 cotton season, Benin was the largest cotton producer in the West Africa region, but from 2021/2022, Mali (1475 thousand bales) became the largest cotton producer, followed by Benin (1300), Cote d’Ivoire (1050), and Burkina-Faso (950) [22], as shown in Figure 1. Examining the volume of cotton trade (import and export operations), sub-Saharan Africa is ranked the third largest cotton producer, with 12% of the overall cotton export. Similarly, according to [23], cotton is a significant contributor to Benin’s rural producers’ income.

Figure 1.

Cotton production in Zone Franc 2021/22.

The growth of the cotton sector as the nation’s mainstay has been confronted with many challenges. Its rising competition from other producer countries, such as Mali and Burkina- Faso [24], lacks textile infrastructures to transform the cotton raw materials into finished textile products [25] (Alidou and Niehof 2020). Therefore, infrastructure deficiencies threaten the hefty political intrusion and interplay within the cotton/textile industries. The political intrusion, in particular, has stalled Benin’s ability to transform its cotton into finished products. Insomuch, importing fake and cheap textile products from Asia, and growing competition from other producer countries in the region [26], is also a significant challenge for the sector in Benin. Some attempts have stimulated the textile industry in the political cycle. Still, it has primarily been confined to strategic thinking [26,27]. The conclusions and recommendations of these considerations were poorly implemented [25]. For example, COTEB and SITEX received one-time financial support from the government. This support was unlikely to revive the industries in the long term. Despite Benin’s strategic and geographical location in West Africa, open to the Atlantic Ocean, it is considered a coastal entry point for the landlocked countries of the hinterland: Niger, Burkina-Faso, and Mali. Benin’s membership in the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) provide access to potential customers. Based on more than 200 million, particularly with a strategic neighbor such as Nigeria, which shares a border of approximately 700 km, as illustrated in Figure 2. Benin has not seized this opportunity and improved its market share.

Figure 2.

Map of Benin in the sub-region with ECOWAS members countries. Source: https://bamada.net/jeu-de-mots-et-manipulation (accessed on 4 October 2021).

Finally, according to IMF’s staff (IMF Report No. 19/203 of June 2019) cited by [28], the development of the industrial sector in Benin is limited by a deficit and the poor quality of infrastructure. Still, it requires governance reforms (in particular, the quality of the investment climate), and technical and financial support to small and medium-sized enterprises, to help them reach critical size by providing targeted tax incentives.

3. Estimation Framework: AHP and SWOT Approach

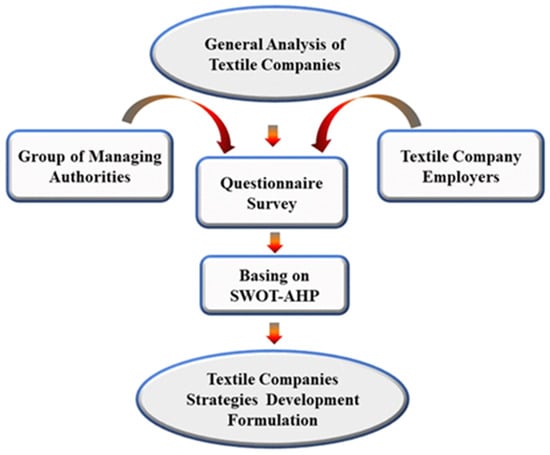

The SWOT technique analyzes interior and exterior priorities in any organization or institution to evaluate its performance [29]. Strength and weakness are considered internal priorities, while opportunity and threats are external factors [30,31]. The SWOT approach delivers a descriptive analysis and evaluation to analyze quantifiable chosen elements [32,33,34] qualitatively. The AHP technique, developed by Professor Thomas L. Saaty in the 1970s, is a decision support solution for multi-criteria problems. This method allows the decision makers’ objective and subjective thinking to be included in the decision-making process through a weighing process [35]. A literature review shows that several studies have been conducted using SWOT and AHP techniques to address many decision-making issues [36,37]. Combining SWOT and AHP, these methods aid in presenting a precise qualitative and quantitative decision. Based on the SWOT/AHP model, the SWOT elements are generated, and then the research survey is evaluated using AHP, as described in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Based on the SWOT/AHP model, the SWOT elements are generated, and then the research survey is evaluated using AHP. Source: authors.

3.1. Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)

AHP offers a systematic conceptual model for such an analytic solution by evaluating the factors to consider and connecting these components to the desired outcome through pair-wise reasoning. This reasoning is converted into numbers that can be compared against all possible criteria [38]. The flexibility of the method has garnered widespread adoption and usage across diverse research fields. For example, using a mix of AHP and Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) approaches, a decision support system (DSS) software for cotton fiber grading and selection was built [39]. The authors used AHP to extract the relative importance or weight of cotton fiber properties. The developed DSS software can classify and select cotton fibers from all aspects of yarn quality. Similarly, a recent study by [40] used AHP to compare fabrics made from three different fibers. This method regenerated bamboo, polyester, and cotton, in terms of their mechanical properties, thermal comfort, and moisture management, to explain the effects of the fibers concerning their suitability for summer consumption. The results of the AHP evaluation in their study showed that regarding the mechanical and thermos-physiological properties related to clothing comfort, 100% cotton fabrics should be preferred for summer clothing. AHP has also been helpful in understanding and addressing other textile-related problems [19]. AHP was used to assess the ecological threat posed by the textile industry to the city of Cuenca, which is traversed by seven rivers. AHP was instrumental in determining the optimal solution for environmental pollution.

Furthermore, AHP has influenced the prioritization of livelihood. These measures support effective and sustainable interventions to reduce poverty in developing countries [41]. AHP also prioritizes identifying suitable cadastral units and informal plots to distribute gardens in urban and suburban areas, while taking into account soil, land use, groundwater, depth, proximity to market, and women’s safety [42].

3.2. Strengths, Weakness, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT)

Several papers have utilized the SWOT method to evaluate organizations’ internal and external performances. For example, Ref. [43] used SWOT analysis techniques and assesses the challenges threatening Pakistan’s textile and clothing industry. The method helped filter the strategic development of the Pakistan’s textile and clothing companies and government executives through an enumerative approach to the industry’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. A similar SWOT analysis was employed by [44] to analyze Turkey’s textile industry. The authors used SWOT analysis to evaluate surveys conducted among university students, heads of school departments, alumni of these schools holding various positions in various fields of work, and the managers of the textile industry in Turkey. The result outlined several recommendations to higher education institutions on the structure and arrangement of teaching syllabus for students pursuing careers in the textile industry [44]. SWOT analysis has been used to conduct individual or sectorial analysis, such as evaluating the efficiency of vapor production processes for cotton-based products.

SWOT and AHP are effective tools used in (MCDM) situations that aid decision-makers in reaching proactive decisions to benefit the institutions they serve. Several papers [45,46,47,48] have combined two methods to supplement the shortfall. SWOT analysis provides a basic schema for analyzing decision-making situations, while the AHP technique offers multiple comparisons among variables or criteria to prioritize them. Combining both methods improves quantitative strategic decision-making [29]. Moreover, Ref. [49] conducted a recent combination of the two methods. Using SWOT and AHP, the authors examined the strategy for long-term development directions for Uzbekistan’s textile companies. Their outcomes highlighted weakness and opportunity (WO) as requiring the most significant attention from the government. In addition, the study found that Uzbekistan calls for a gradual change in its industrial structure, ranging from raw cotton to finished textile export, which provides a valuable addition.

As we previously stated, several studies applied SWOT and AHP analysis to suggest development strategies for the textile industry across the world; but in Benin, no one has applied such an approach in research work. Based on our review of this literature, we established a SWOT matrix by classifying, organizing, and integrating, the SWOT factors identified in those studies with the AHP method for decision-making.

The literature survey exhibits a lack of a holistic approach for assessing Africa’s textile industry, especially in Benin, with the SWOT and AHP approach. From our point of view, this project is the first initiative to assess and evaluate Benin’s textile industry performance by applying the combination of these two MCDM methods.

3.3. Causal Link

To this end, our survey of previous literature shows a lack of a holistic approach to assessing Benin’s textile industry. Few scholars have analyzed the performance of textile performance in Benin, such as [7]. Moreover, this study aims to revive the textile industry to be competitive, robust, and attractive; therefore, it has become a paramount concern for all parties involved, especially the state with its strategic partners. For a sustainable recovery, the path to international partnerships can be seen as attractive for private buyers to take over lease administration or acquire the struggling textile industry.

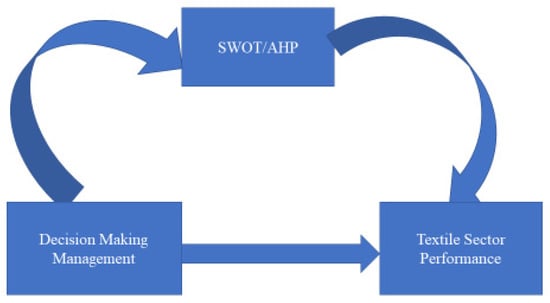

Given the importance of the cotton sector to the Beninese economy, and for all the actors involved, it is imperative to conduct research and offer recommendations to enrich the development of the industry. This research aims to bridge the gap between textile companies and government involvement in the cotton-textile sector by exploring how Beninese textile industries deal with their challenges. In doing so, we seek to understand what challenges affect Beninese textile productivity by addressing two hypotheses: (H1) Managerial factors influence the performance of textile productivity; and (H2) SWOT/AHP analysis mediates the relationship between decision-making and productivity, and Figure 4 illustrates this causal link.

Figure 4.

Shows the causal link of the study. Source: authors.

4. Methodology

In order to achieve the objectives of this study, the methodological approach that has been used is based on the exploitation of information obtained from both primary and secondary sources. This information was processed and analyzed not only according to the objectives, but also according to its nature. Nevertheless, the methodological choices made to achieve the various objectives were justified by constraints on the availability of statistical data. Because of these data constraints, the methodological choices consisted of carrying out descriptive analyses of the evolution of the variables, for which the data are available, and harmonizing the data coverage within the framework of the causal analyses to have all the variables concerned by these analyses—applying the AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process) and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) methods to make proper analysis after a wide range of surveys to provide guidance about the resilience of the textile industry in Benin. The SWOT-AHP approach was employed with secondary data sources. Our study, which ran from December 2019 to July 2020, focuses on the textile production units in Benin, including a few units which have entered a state of cessation. Following this path, our study aims to extract the critical rationales behind the dismal performance of the cotton industry in Benin, their managerial shortfalls, and the causes for the collapse of some enterprises (COTEB), or the near-closure of some factories (SITEX, CBT).

Our sample population comprises managers responsible for different sections of their plants and the members of the country’s decision-making bodies (the Ministry of Industry, the Board of Directors, etc.). Our primary respondents are key decision-makers in these textile institutions because they are essential for understanding the vision and strategies implemented for development and the difficulties encountered by their companies. Additionally, the population interviewed for this study consists of current and former managers at various levels of their companies. This technique develops a deeper understanding of each company’s difficulties, both from past and present data. Secondly, we surveyed the union workers. The second category of our survey consists of employees of these associations, whom we interviewed to gather opinions on the management of their companies. We administered 200 questionnaires. A total of 195 replies were received, and 172 samples were deemed applicable in the context of our study. Because of their responses, the other 23 samples were inconsistent after the consistency of ratio during the survey. The consistency index may calculate the consistency of ratio (CR) significance for AHP over the random consistency index (RI). The n value = 4 when RI is 0.90. We anticipated the feedback to be acceptable when CR is less than 10%.

With n number of factors

RI arbitrary index

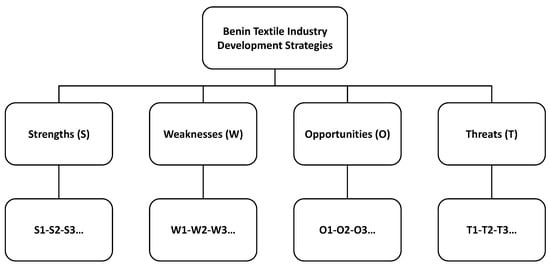

The third step of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis, as well as many factors included in each step, is described in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

A description of the third step of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis, as well as some factors included in each step. Source: authors.

The results of the literature research, our observations in the field, interviews, and our analysis of the questionnaires generated from these interviews, form the basis of our research. Therefore, this analyzes the development of the textile industry and highlights the key challenges that this research aims to address. Our questionnaire was structured around Saaty’s research [50] to extract priorities within each SWOT group. We also employed multiple comparison criteria in each SWOT group as the core of our questionnaire, because various comparison factors create a complex and diversified view from respondents.

The maximum number of pair-wise comparison components should not exceed 7 ± 2 [50].

The notion of pair-wise evaluation is vital in the analytical hierarchic process.

A relatively significant value (known as weight) is produced during the pair-wise comparisons. Figure 3 indicates the hierarchical shape to rank the SWOT elements. The taken invoice of weights can be obtained through the eigenvalue methodological analysis Equations (3) and (4) in case of inconsistency within the matrix.

where

As illustrated in Figure 3, the SWOT-AHP matrix for this study has four SWOT groups, with three variables for strengths and opportunities each, five for weaknesses, and four for threats. Table 1 lists (Saaty 2008) AHP nine-point scaling schemes for evaluating relative importance, which we adopted for the questionnaire.

Table 1.

AHP, Saaty’s 1–9 scale was used.

These chosen methods are essential for this research because they will help evaluate the critical factors in strategic planning, increase the awareness of the factors that go into making a business decision, and utilize them in developing effective strategies for Benin textile companies. It would also be crucial for policy-makers to understand the relative importance of environmental factors, to support and impact the viability of their decision-making process. Finally, it will help set business strategies to improve competitiveness or business performance, making investments in technologies, geographical locations, or markets.

5. Results and Discussion

To assess the textile companies’ performance (output), we employed the AHP and SWOT analysis. This study highlights the need for foreign investment to overcome resource constraints and increase the competitive nature of the industry. We argued that the state might play a regulatory rather than a decision-making role in addressing the obsolescence of technological installations and energy sources. Suitable analytical solutions and strategy development are recommended following the groups’ priorities and SWOT elements on four divisions (SO, ST, WO, and WT). The relative significance worth of weight (or the decision-opinion) makers are then produced in the AHP and later calculated using the eigenvalue approach. The rating matrix A conducts the assessment data in pairs.

where

a = entries;

n = number of parameters.

The AHP measures theory that focuses on mathematical and psychological concepts can include primary and secondary data collection features. AHP analysis forms priorities for decision alternatives used in SWOT to evaluate factors to determine intensities [49] (Kim and Park 2019). The SWOT analysis results can be generated by making multiple combinations between the SWOT elements and the analysis using the eigenvalue technique applied in the AHP. This provides a solid basis for assessing current or anticipated situations to develop new substitute strategies [51] (WICKRAMASINGHE and TAKANO 2010). Following this phase, a decision-maker has new quantitative information on the decisions to be made, such as whether certain vulnerabilities require full attention, or whether there are likely to be future consequences or threats. Additionally, if one weakness outweighs all the strengths, the chosen strategy can be adjusted to mitigate or ease that weakness. Choosing new strategies may not be based solely on the opportunities and threats that exist when they are of equal magnitude. We define four SWOT clusters, each comprising four factors or groups (15 altogether) for the Beninese textile industry. We employed a similar procedure as in [49] research to analyze the relative importance of each SWOT group to determine the factors in the SWOT group’s priorities with a CR value of 0.1 or below. We then create a SWOT scaling mechanism using AHP to prioritize each factor relevant to the strength and dynamism of the Beninese textile industry. In contrast to our findings, previous studies have used the SWOT and AHP methods to identify and evaluate the performance for better decision-making in different sectors. In the textile sector, some studies such as [29,52,53] used SWOT or the combination with AHP to identify the specific problem for better strategic development

5.1. Empirical Assessment & Elaboration of Development Strategy Statement

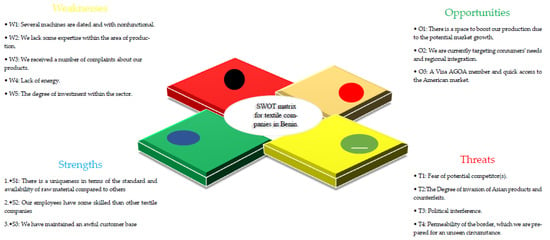

Formulation of the SWOT Matrix

It is noteworthy that after subsequent rounds of professional consultation and revision, we discovered that the SWOT features emerged multiple times and decided on the appropriate criteria to apply for this investigation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

SWOT analysis model. Source: authors.

5.2. SWOT-AHP Analysis

Using [49] approaches, we developed a three-level hierarchical SWOT-AHP model. As shown in Figure 7, our AHP analysis for the four groups of SWOT matrices comprises 15 factors of each SWOT group to implement a strategy to develop a textile company in Benin.

Figure 7.

SWOT-AHP analysis. Source: authors.

As previously explained, we maintained a CR below 0.1 to analyze the logical consistency of the survey and Table 2 details the demography of our respondents.

Table 2.

Demography of respondents.

For numerical computations, we adopt three spectrums (verbal, graphical, and numerical) from our assessment to enter multiple comparison data, since it is the most effective for entering coding matrix data obtained from the outcome of this investigation. Furthermore, we utilize the principle of the distributive model to compute the priority based on the eigenvectors. Similarly, building on the principle of [49], we determine significant weights by dividing the local weight by the global weight. After setting up these mechanisms to assess the importance of the SWOT groups, textile industry professionals in Benin were asked to assess the importance of internal strength and weakness groups. The overall priority scores of SWOT factors (Table 3) revealed more deficiencies, such as the obsolescence (0.26) of technology equipment between 1980 and 1990, with high energy intensity (0.175). Many complaints were received about the products (0,164) because of the high intensity of labor, low productivity, and expertise in production (0.157). The result also suggests that the state’s clumsy intervention seriously threatens internal project control (0.097). Additionally, the result shows that more opportunities are available, such as a potential growing market (local-regional) (0.087) and Visa AGOA (0.039).

Table 3.

Overall priority scores of SWOT factors.

5.3. Discussion

The efficiency of textile production is determined by the key performance indicators [54,55,56]. Each company needs to provide a mechanism to position itself by its competition and competition plan. [57] showed that McKinsey and Company established performance criteria in the 1960s to monitor and evaluate the management factors that influence the development of a company. The parameters that contribute to company growth differ by business type. Textile mills evaluate their performance based on mill capacity factors that include production capacity, capacity utilization, employment curve, and installed and actual yields. Other indicators are the cost of production, selling price, technology readiness, and managerial competence [58,59,60]. These essential indicators of performance determine the competitiveness of the production of textile factories. This research analyzed a diagnosis of the resilience of Benin’s textile firms. A SWOT matrix of given textile companies in Benin has been developed (Figure 6). This framework captured the essential environments of the sector and objectified them from the general literature, while evaluating the critical issues of the sector. The local and global priority of SWOT factors were calculated, and the results were illustrated with a graphical interpretation in Figure 7, and Table 3 demonstrates the result of the relative weight scores of the SWOT group. The results of the criteria weighting, as shown in Table 3, have met the CR standard, where the maximum CR value is 0.1. The analytical result highlights the need for private capital to resolve technical challenges and boost the industry’s competition by examining its significant weaknesses, such as dated technological installations and implementation of the source energy. Succinctly, evidence from other studies [61,62,63] also explains the same problems that face others textile companies in India, Bangladesh, and Uzbekistan. The difference in the study compared to those countries is that their governments do not have a monopoly on companies. For industrial sustainability, raw material availability [64] and technology are crucial in creating added value for society and organizations performance [65].

Sustainable Strategies for Benin Textile Industry

Several conclusions can be drawn from Table 3, which lists the local group priority factor (L-weight) and the global priority (G-weight) within each group. W1, W4, W3, and W2, are weaknesses ranked in order of weight with the potential to empower by strengths S1 and S2 through opportunities O1 and O3 at the same minifying threats T3. The outcome of the SWOT-AHP analysis calls for adjustments in Benin’s textile sector, combining SO as strengths and opportunities, WO complement weaknesses, ST as strengths to overcome threats and exploit opportunities, and WT to minimize weaknesses and counteract threats. The developmental strategies of the textile industry can be divided into four categories: SO, ST, WO, and WT. S1 and S2 are relatively important in the strength group, while O1 and O3 are necessary for the opportunity group. Benin’s textile products have been perceived to be exceptional at the local and sub-regional levels. Because raw materials are readily available, it is necessary to take advantage of the benefits of agreements signed by Benin on the movement of goods and people (free trade throughout the West African zone) and become a member of WAEMU and Visa Africa AGOA. Among the most pressing issues that threaten Benin’s manufacturing industries in the treatment group is the role of the state T3. It raises several important questions: can the state give more added value? Does it harm the sector? Indeed, the finding demonstrates that although the technologies used in the textile industry are dated, the state’s involvement does not favor the emergence of these companies, but rather their instrumentalization. This is explained by its intervention and involvement in the management process.

Therefore, creating an appropriate framework through public-private collaboration is vital to strengthen and using the institutional and organizational framework of textile enterprises in Benin. This would allow coordinated decision-making and eliminate its instrumentalization through state intervention. Therefore, for the ST strategy, it is appropriate to establish and conduct ongoing sectoral consultations in both public and private sectors to ensure the sector’s competitiveness and eliminate some government presence that negatively influences industry performance. This action does not call for the state to back down in its entirety, but rather to avoid manipulations through its intervention and influence opportunities for business diversification. According to the following result, W1 (0.26), W4 (0.175), W3 (0.164), and W2 (0.157), are of relatively higher importance in the weaknesses group. It suggests that the government promotes, creates, and supports, integrated value chains.

Further, we argue that the state advocates local foreign investment and local processing accessibility to raw materials. It will enable Benin’s textile industry to take full advantage of the market growth in the sub-region. As indicated in the strengths + treats (ST) and strengths + opportunities (SO) combination plans, it is essential to address the deficiencies and respond to the external situation of the companies, with a focus on the cotton sector (raw material). It means a dire need to develop a specific diversification strategy.

Textile companies are advised to establish partnerships with overseas companies looking for foreign direct investment or strategic technological partnerships to address the weaknesses, while safeguarding and maximizing opportunities. Finally, the WT strategy adds the most critical vulnerability elements (W1, W4, W3, W2, and W5), while eliminating T3, one of the most important threat factors. As stated in WO and ST strategies, the goal ought to enhance inadequate infrastructures, such as outdated machines, the lack of energy, and the lack of real expertise in production, as found in China. In addition, the meager investment in the sector has consequences on importing raw materials (cotton). According to [49], the study carried out on the sustainable development strategy of Uzbekistan’s textile industry, and corresponding to our research, revealed that the government needs to upgrade obsolescent technology and solve the problems of high-priced imported raw materials, and the workers’ low-level of education, and should gradually shift the industrial structure from raw cotton to finished textile exportation, which offers relatively high added economic value by promoting joint ventures and alliances with foreigners’ companies. The slight difference between Uzbekistan and Benin companies is that government has no harmful effects of the monopoly system, which impeded the management of these companies. These are a few examples of Benin’s textile industry weaknesses that, when resolved, will intensify competition within the textile industry. This study was primarily limited by its relatively small sample. An early data collection would have increased the time needed to survey more participants. Other limitations of this study included some degree of possible measurement errors, although we attempted to minimize them. The study’s weaknesses also lie in the various components of SWOT elements identified through the literature review. In addition, the AHP analysis has restricted the number of elements per component to four, recognizing that a more significant number of components to be examined would exacerbate logical consistency in maintaining logical solutions.

6. Conclusions

Benin’s textile companies face many challenges. Unlike previous studies [39,66,67,68,69,70] that concentrate on the socio-economic concerns of entrepreneurial groups, this paper goes a step further by highlighting the critical SWOT-AHP analysis of Benin’s textile industry, which also applies to other developing nations, such as Mali and Burkina-Faso, both major cotton producers. According to current African textile industries, countries like Benin face numerous challenges, such as a lack of managerial resources and financial expertise, which impede their survival. Those enterprises need to be revitalized. Therefore, this article offers some critical strategic ideas for resolving these difficulties. Government intervention is required as a policy-maker for their revival. For example, in Bangladesh, the government played an active role in the sector’s development by lifting limitations on foreign investment. More specifically, the study reviews [71] the historical experiences of Bangladesh, Cambodia, Lesotho, and Madagascar, and explains the roles played by various foreign investors in contributing to upgrading. This has important policy implications, suggesting that government policies aiming to develop the garment sector beyond the assembly stage must correctly identify and attract the most likely to be or become embedded investors. Similarly, Ref. [69] contends that Ethiopia has multiple vertically integrated textile companies and some multinational firms, creating vertically integrated garment factories because of government policy. This sets it apart from most sub-Saharan African countries that export garments.

The findings show that textile enterprises in Benin face numerous challenges that impede their survival and need to be revitalized. As a result, this article offers some critical strategic ideas for resolving these difficulties. According to the current research, those enterprises in Benin need to be revitalized. In addition, foreign investment is required to overcome resource constraints and increase the competitiveness of companies (dated machines and electricity shortage). Furthermore, the state should take a regulatory role rather than a decision-making role, as the poll discovers that state choices have significantly impacted the managerial ability of these businesses. Thus, the government must implement many programs that encourage textile enterprises to develop capital-intensive textile items, especially products and foreign brands [68]. Because these concentrations serve as the role of public intermediaries in revitalizing the textile sector, Ref. [66] encourages local and national manufacturing companies to grow to produce for domestic and international markets. In addition, it will also contribute to reducing youth unemployment, which will lead to global poverty. Following the SWOT-AHP analysis, we argued that the Beninese government might need to emphasize upgrading the limited level of technology and ensure the raw material availability for manufacturing companies.

The Beninese government is likely to progressively reorient the industrial structure from raw cotton to the export of processed textiles, providing added value to the national economy. We suggest that the government stimulate partnerships and alliances with foreign companies wishing to join the textile industry through FDI to accomplish this. By creating a framework of standard procedures that will help operators in the textile sector continually improve their performance, while creating opportunities for future generations, this research can help enhance sustainable development in Benin. Finally, the investigation is likely to be more helpful in understanding the importance and priorities of the AHP and investigating the causal links among the essential factors influencing the development of Benin’s textile sector through a structured model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, methodology and writing, review and editing, C.S.N.D., F.C. and P.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning, Project (21NDJC065YB).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The main datasets were generated from intensive survey, interview and the National Institute of Statistics during more than 1year and half investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning. Project: Research on the Synchronization and impact Effect of Technology Migration in the Process of industrial Transfer for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

References

- Cushion, S. Review of Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Rev. Hist. 2016, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanet, K.; Chiamaka, E.O.; Quansah, G.W.; Mubeen, M.; Farid, H.U.; Akram, R.; Nasim, W. Cotton Production in Africa; John & Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergely, N. The Cotton Sector of Côte D’Ivoire; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonou-Zin, R.D.; Allali, K.; Fadlaoui, A. Environmental Efficiency of Organic and Conventional Cotton in Benin. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, H. Cotton in West and Central Africa: Role in the regional economy & livelihoods and potential to add value. In Proceedings of the the FAO Natural Fibres Symposium, Rome, Italy, 20 October 2008; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Assogba, S.C.G.; Tossou, R.C.; Lebailly, P.; Magnon, Y. Sustainable intensification of agriculture in Benin: Myth or reality? Lessons from organic and cotton made in Africa production systems. Int. J. Agric. Innov. Res. 2014, 2, 694–704. [Google Scholar]

- Igor, T.; Ahokp, A. Analyse de la Résilience des Industries Textiles du BÉNIN: Le cas du Complexe Textile du Bénin (COTEB). Master’s Thesis, University of Quebec, Quebec, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe, K. Quantitative Assessment of Sustainable Development and Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitaire Pers Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdell, C.A. Sustainable Development and Conservation Chapter 11. In Economics of Environmental Conservation, 2nd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chelthenam, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muthu, S.S. Evaluation of Sustainability in Textile Industry; Springer: Singapore, Singapore, 2016; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relance, S.D.E.; Pole, D.U. Evaluation Ex-Ante de la Mise en Œuvre des Strategies de Relance du Pole Co-Ton-Textile au Benin; Ministère de l’Economie et des Finances du Bénin: Cotonou, Bénin, 2010; Available online: http://www.slire.net/document/1932 (accessed on 9 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- ECOWAS-SWAC/OECD. Atlas on Regional Integration. Chapter produced by Christophe Perret under the supervision of Laurent Bossard Assistant. 2006. Available online: www.oecd.org/sah; www.ecowas.int (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Daviron, B.; Gibbon, P. Global Commodity Chains and African Export Agriculture. J. Agrar. Chang. 2002, 2, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahofa, G. Economic Analysis of Factors Affecting Cotton Production in Zimbabwe. Master’s Thesis, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe, July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, G. African Economic Development and Colonial Legacies. Rev. Int. Polit. Développement 2010, 1, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Dhaliwal, N.S.; Bishnoi, C. Adoption Status of Improved Crop Production Practices in Bt-cotton in Sri Muktsar Sahib, Punjab. Indian J. Ext. Educ. 2021, 57, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Coronel, C.I.; Carrion, G.L.; Quezada, C.M.; Escandon, E.A.B. AHP Analysis to Minimize the Effects Produced by the Textile Industry in the Rivers of Cuenca City; IEEE: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, A. Sahel and West Africa Club How is life in West Africa’s cities? West African Pap. Publ. 2021, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Commodity Intelligence Report. 2019. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/highlights/2012/08/Mexico_corn/ (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- United States Department of Agriculture. Commodity intelligence report. Foreign Agric. Serv. Rep. 2021, 10, 1–9. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/highlights/2021/07/India/index.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- PASCiB. La filière coton au Bénin. In La filière Cot. au Bénin, regard Anal. Prospect. la société Civ; Plateforme des Acteurs la Société Civ. au Bénin (PASCIB): Cotonou, Benin, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, J. Cotton Dependence in Burkina Faso: Constraints and opportunities for balanced growth. In Yes, Africa Can Success Stories from a Dyn. Cont; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Alidou, G.M.; Niehof, A. Responses of Rural Households to the Cotton Crisis in Benin. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpadé, C.P.; Mensah, E.R.; Fok, M.; Ndjeunga, J. Cotton farmers’ willingness to pay for pest management services in northern Benin. Agric. Econ. 2016, 48, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prag, E. ASR Forum: Engaging with African Informal Economies. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2013, 56, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generale, D.; Affaires, D.E.S.; Des, D.; Sectorielles, P. Industrialisation au Bénin: Etat d’ Évolution, Facteurs Explicatifs et Perspectives de son Développement; Ministère de l’Economie et des Finances du Bénin: Cotonou, Benin, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Görener, A.; Toker, K.; Uluçay, K. Application of Combined SWOT and AHP: A Case Study for a Manufacturing Firm. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osita, I.; Onyebuchi, I.; Nzekwe, J. Organization’s stability and productivity: The role of SWOT analysis an acronym for strength, weakness, opportunities and threat. Int. J. Innov. Appl. Res. 2014, 2, 23–32. Available online: http://www.journalijiar.com (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis of China’s Prevention and Control Strategy for the COVID-19 Epidemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, I.; Kim, H.; Kang, J. SWOT-AHP analysis of the Korean satellite and space industry: Strategy recommendations for development. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 164, 120515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, X.; Fang, Y. The Development Strategy of Home-Based Exercise in China Based on the SWOT-AHP Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pournabi, N.; Janatrostami, S.; Ashrafzadeh, A.; Mohammadi, K. Resolution of Internal conflicts for conservation of the Hour Al-Azim wetland using AHP-SWOT and game theory approach. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Mukul, E.; Kongar, E. Health tourism strategy selection via SWOT analysis and integrated hesitant fuzzy linguistic AHP-MABAC approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 74, 100929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Falcone, P.M.; Gastaldi, M.; Morone, P. Corrigendum to ‘RES-T trajectories and an integrated SWOT-AHP analysis for biomethane. Policy implications to support a green revolution in European transport. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, K.; Mehri-Tekmeh, J.; Karimi, S. A SWOT framework for analyzing the electricity supply chain using an integrated AHP methodology combined with fuzzy-TOPSIS. Int. Strat. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, M.M.A.; Al-Shamma’A, A.M.; Al Maliki, A.; Hussain, H.M.; Yaseen, Z.M.; Armanuos, A.M. Integrated Water Harvesting and Aquifer Recharge Evaluation Methodology Based on Remote Sensing and Geographical Information System: Case Study in Iraq. Nonrenew. Resour. 2021, 30, 2119–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; Mangla, R.; Gupta, A. Developing a decision support system software for cotton fibre grading and selection. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2010, 35, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Saricam, C.; Erdumlu, N. Evaluation of Regenerated Bamboo, Polyester and Cotton Knitted Fabrics for Summer Clothing. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2018, 26, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffoe, G. Exploring the utility of Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) in ranking livelihood activities for effective and sustainable rural development interventions in developing countries. Eval. Program Plan. 2018, 72, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneveld, B.; Houessou, M.; Boom, G.V.D.; Aoudji, A. Where Do I Allocate My Urban Allotment Gardens? Development of a Site Selection Tool for Three Cities in Benin. Land 2021, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seher, K.; Aftab, A.S.; Hussain, P.M.; Turan, A. SWOT analysis of Pakistan’s textile and clothing industry. Ind. Text. 2019, 69, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işgören, N.; Ayla, C. Evaluation on textile-apparel education by Swot analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2009, 1, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, M.; Smarandache, F. An Extension of Neutrosophic AHP–SWOT Analysis for Strategic Planning and Decision-Making. Symmetry 2018, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.; Mohsin, M.; Abbas, Q.; Chaudhry, I.S. Correction to: Assessing the integration of solar power projects: SWOT-based AHP–F-TOPSIS case study of Turkey. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 43421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariyana, R.; Amalia, R.; Salsabilah, D.S.; Uka, A.S.; Rilisa, C.; Gunawan, W. Strategy for increasing lowland rice productivity in West Java Province with the SWOT-AHP model approach. IOP Conf. Series Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 457, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashutosh, A.; Sharma, A.; Beg, M.A. Strategic analysis using SWOT-AHP: A fibre cement sheet company application. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Park, J. A Sustainable Development Strategy for the Uzbekistan Textile Industry: The Results of a SWOT-AHP Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, V.; Takano, S. Application of Combined SWOT and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for Tourism Revival Strategic Marketing Planning: A Case of Sri Lanka Tourism. J. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2010, 8, 954–969. [Google Scholar]

- Iriani, Y. Strategic Management of Enterprises in the Tannery Industry: By an Integrated Deployment of SWOT Analysis and AHP Method. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 301–307. [Google Scholar]

- Joo-in, K.; Baek, N.; Lee, J.K. AhpSelection Model and Application of Overseas Location in Sewing and Clothing Manufacturing Industry Using. J. Korean Soc. Saf. Manag. Sci. 2014, 16, 377–388. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-O.; Traore, M.K.; Warfield, C. The Textile and Apparel Industry in Developing Countries. Text. Prog. 2006, 38, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, C.-F.; Tan, S.; Yan, J.; Starfelt, F. Key Performance Indicators Improve Industrial Performance. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 1785–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahija, S.; Shehi, E.; Guxho, G. Evaluation of production effectiveness in garment companies through key performance indicators. Autex Res. J. 2012, 12, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasiel, E.M. The Mckinsey Way Using the Techniques of the World’s Top Strategic Consultants to Help You and Your Business; McGraw Hill (India): Uttar Pradesh, India, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, C. China in Africa. Survival 2005, 47, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadman, H.G. Africa’s Silk Road; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Okafor, E.E. Development Crisis of Power Supply and Implications for Industrial Sector in Nigeria. Stud. TRIBES TRIBALS 2008, 6, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Khan, A.M. Textile Industries in Bangladesh and Challenges of Growth. Res. J. Eng. Sci. 2013, 2, 31–37. Available online: www.isca.in (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Muhammad, M. Kano Textile Industry and the Globalisation Crisis. J. Res. Natl. Dev. 2011, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrivel, K. Challenges of textile Industry in Karur Taluk. Glob. Dev. Rev. 2021, 5, 16–19. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/356032480_challenges_of_textile_Industry_in_Karur_Taluk (accessed on 14 August 2022).

- Muzayyanah, I.; Mahmudy, W. Bahan baku dan membantu target marketing industri dengan metode fuzzy inference system Tsukamoto. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universitas Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia, 2014. Available online: http://wayanfm.lecture.ub.ac.id/files/2015/06/JurnalSkripsi-2013-2014-009-Iklila-Muzayyanah.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Roblek, V.; Meško, M.; Krapež, A. A Complex View of Industry 4.0. SAGE Open 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghal, G.U.; Pathan, P.A.; Mughal, S.; Saeed, S. An Empirical Analysis of Socio-Economic Determinants of Working Women in Textile Industry: A Case Study of Hyderabad, Sindh, Pakistan. Women Ann. Res. J. Gend. Stud. 2016, 8, 180–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, B.-K.; Phelps, N.A. From ugly ducklings to beautiful swans? The role of local public intermediaries in the revival of the Daegu textile industry. Geoforum 2018, 90, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, T.R.; Shah, D.S.A.S.; Bhatti, K.-R. Women’s Home-Based Handicraft Industry and Economic Wellbeing: A Case Study of Badin Pakistan. Women, Res. J. 2016, 8, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pepermans, A. China as a Textile Giant Preserving its Leading Position in the World, and What it Means for the EU *. Political Sci. 2019, 80, 63–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staritz, C.; Frederick, S. Harnessing foreign direct investment for local development? Spillovers in apparel global value chains in sub-Saharan Africa. Dev. Res. 2016, 59, 1–27. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/149909 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Calabrese, L.; Balchin, N. Foreign Investment and Upgrading in the Garment Sector in Africa and Asia. Glob. Policy 2022, 13, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).