Optimistic Belief in One’s Own Capableness as a Factor of Entrepreneurial Sustainability: The Assessments of Self-Efficacy from the Perspective of Serbian Entrepreneurs

Abstract

1. Introduction

Self-Efficacy as an Optimistic Belief in One’s Own Capableness

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

- Significant, moderately strong and positive relationships with the questions: “I have clear beliefs and expectations about my work” and “I have all the skills and habits to be a successful entrepreneur”;

- Significant, moderately strong and negative relations with the question: “I find it difficult to deal with stressful situations at work”;

- Significant, weak and positive relationships with the questions: “I sometimes panic when direct competition appears,” where this relationship is of low intensity and negative.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Not at All True | Hardly True | Not Sure | Moderately True | Exactly True |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I find it difficult to deal with stressful situations at work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I compare myself to others when I judge how successful I am in business. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I have clear beliefs and expectations about my work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Recognition from my colleagues serves as a confirmation that I am doing my job well. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I sometimes panic when direct competition appears. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I clearly understand and value myself. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I have all the skills and habits to be a successful entrepreneur. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I learn from bad business moves. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Question | Answers |

|---|---|

| 1. Gender: | (a) Man (b) Woman |

| 2. Education: | (a) Secondary education (b) Higher (Post-secondary) education (c) University education (Bachelor’s degree) (d) Master’s degree or doctorate |

| 3. Age: | (a) 25 to 34 years old (b) 35 to 44 years old (c) 45 to 54 years old (d) 55 to 64 years old |

| 4. How long have you been an entrepreneur? | (a) 1–3 years (b) 3–6 year (c) 6–10 year (d) 10–15 year (e) 15–20 year (f) Over 20 years |

| 5. How satisfied are you with your current job? | (a) I am extremely dissatisfied (b) I am very dissatisfied (c) I am partially dissatisfied (d) I am partially satisfied (e) I am very satisfied (f) I am extremely satisfied |

| 6. What is your monthly income? | (a) Less than 300 euros (b) 300–600 euros (c) 600–1000 euros (d) 1000–3000 euros (e) 3000–6000 euros (f) 6000–10,000 euros (d) Over 10,000 euros |

References

- Sokić, J.; Popov, S. Osobine ličnosti uspešnih preduzetnika [Personality traits of successful entrepreneurs]. TIMS. Acta 2009, 13, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurović, A. Zapošljavanje Mladih i Preduzetništvo—Ključni Izazovi Javnih Politika na Zapadnom Balkanu [Youth Employment and Entrepreneurship—Key Challenges of Public Policies in the Western Balkans]; Beogradska Otvorena Škola: Beograd, Serbia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Udovički, K. (Ed.) Preduzetništvo u Srbiji: Nužda ili Prilika? [Entrepreneurship in Serbia: Necessity or Opportunity?]; Centar za Visoke Ekonomske Studije (CEVES): Beograd, Serbia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pokrajac, S.; Tomić, D. Preduzetnici kao ključni činioci stvaranja preduzetničkog društva [Entrepreneurs as key factors in the creation of an entrepreneurial society]. Škola biznisa 2009, 2, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, S.P.; Kerr, W.R.; Xu, T. Personality traits of entrepreneurs: A review of recent literature. Found. Trends Entrep. 2018, 14, 279–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offe, C. Modernity and the State: East, West; Wiley: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, K.I.; Mahmood, S.; Tariq, M. Fostering digital entrepreneurship through entrepreneurial perceptions: Role of uncertainty avoidance and social capital. J. Bus. Econ. 2021, 13, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Keilbach, M. Entrepreneurship capital and economic performance. Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, O.; Roman, A.; Rusu, V.D. The nexus between entrepreneurship and economic growth: A comparative analysis on groups of countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Audretsch, D.B.; Braunerhjelm, P.; Carlsson, B. Growth and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 39, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Entrepreneurship for sustainable development: A review and multilevel causal mechanism framework. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 44, 1141–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J. What Factors Are Necessary for Sustaining Entrepreneurship? Sustainability 2019, 11, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsen, K. Entrepreneurship as organizing. In Proceedings of the Presentation Paper: DRUID Summer Conference, Bornholm, Denmark, 9–11 June 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Campo, J.L.M. Analysis of the influence of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions. Prospect 2010, 9, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M.; Rialp, J.; Urbano, D. The impact of desirability and feasibility on entrepreneurial intentions: A structural equation model. Int. Entrepreneurship Manag. J. 2006, 4, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.D.; Gartner, W.; Greene, P.G.; Cox, L.W. The Entrepreneur Next Door: Characteristics of Individuals Starting Companies in America: An Executive Summary of the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics. SSRN Electron. J. 2002, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, T. Self-employment Entry across Industry Groups. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervo, H.; Ritsilä, J. Effects of Unemployment on New Firm Formation: Micro-Level Panel Data Evidence from Finland. Small Bus. Econ. 2002, 19, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy in the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanbi, S.T. Familial factors, personality traits and self-efficacy as determinants of entrepreneurial intention among vocational based college of education students in Oyo state, Nigeria. Afr. Symp. Online J. Afr. Educ. Res. Netw. 2013, 13, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, H.; Ma, Z.; Jiao, S.; Chen, X.; Lv, X.; Zhan, Z. The Sustainable Personality in Entrepreneurship: The Relationship between Big Six Personality, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Intention in the Chinese Context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R.; Bandura, A. Impact of conceptions of ability on self-regulatory mechanisms and complex decision making. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.E. Academic Self-efficacy and the Overprediction of African American College Student Performance. Unpublished Dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, M. What is self-efficacy? Bandura’s 4 sources of efficacy beliefs. Positive Psychology UK. 2008. Available online: http://positivepsychology.org.uk/self-efficacy-definition-bandura-meaning/.22 (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Boyd, N.G.; Bozikis, G.S. The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Baum, J.R. Entrepreneurial Motivation. In The Psychology of Entrepreneurship; Baum, J.R., Frese, M., Baron, R.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, G.; Borgia, D.; Schoenfeld, J. Using social cognitive career theory to predict selfemployment goals. N. Engl. J. Entrep. 2002, 5, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wong, P.; Lu, Q. Tertiary education and entrepreneurial intentions. In Technological Entrepreneurship; Phan, P., Ed.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2002; pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Support for the development of the food industry. Poljoprivrednik 2021, 8, 1.

- Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Vojvodina. Economic Potentials of Vojvodina—Food Industry. 2009. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8xGQNDQXPg (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Jardim, J. Competências empreendedoras. In Empreendipédia—Dicionário de Educação para o Empreendedorismo; Jardim, J., Franco, J.E., Eds.; Gradiva: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019; pp. 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Laviolette, E.M.; Radu Lefebvre, M.; Brunel, O. The impact of story bound entrepreneurial role models on self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 720–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R.L.; Dimitriadi, N.; Gavidia, J.V.; Schlaegel, C.; Delanoe, S.; Alvarado, I.; Wolff, B. Entrepreneurial intent: A twelve-country evaluation of Ajzen’s model of planned behavior. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crant, J.M. Proactive behavior in organizations. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.H.; Yu, Y.M.; Chang, W.Y.; Lin, Y.K. Social support and factors associated with self-efficacy among acute-care nurse practitioners. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 876–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Feng, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, S.; Ge, Z.; Pan, Y. The mediating role of general self-efficacy in the association between perceived social support and oral health-related quality of life after initial periodontal therapy. BMC Oral Health 2016, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V.; Petrillo, G. Organizational efficacy, job satisfaction and well-being: The Italian adaptation and validation of Bohn Organizational Efficacy Scale. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, W.; Cooper, D.; Penz, K. Hope, self-efficacy, spiritual well-being and job satisfaction. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 2376–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, M.; Jovanović, V.; Gavrilov-Jerković, V. The general self-efficacy scale: New evidence of structural validity, measurement invariance, and predictive properties in relationship to subjective well-being in Serbian samples. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A.; Gutiérrez-Doña, B.; Schwarzer, R. General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. Int. J. Psychol. 2005, 40, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Mao, C. The impact of person–job fit on job satisfaction: The mediator role of Self efficacy. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 121, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Del Pino, R.M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy as predictors of overall self-esteem in nursing by years of experience. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filion, L.J. Defining the entrepreneur. In World Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship; Dana, L.-P., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Ashford, S.J. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Hu, B.; Xu, Z.; Li, Y. Employees’ psychological ownership and self-efficacy as mediators between performance appraisal purpose and proactive behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jerusalem, M. General Self-Efficacy scale. In Measures in Health Psychology: A User’s Portfolio. Causal and Control Beliefs; Weinman, J., Wright, S., Johnston, M., Eds.; NFER-NELSON: Windsor, UK, 1995; pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, I.; Khan, M.B.; Shahab, A.; Hameed, I.; Qadeer, F. Science, technology and innovation through entrepreneurship education in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Sustainability 2016, 8, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.F.; Khan, K.I.; Saleem, S.; Rashid, T. What factors affect entrepreneurial intention to start-ups? The role of entrepreneurial skills, propensity to take risks, and innovativeness in open business models. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

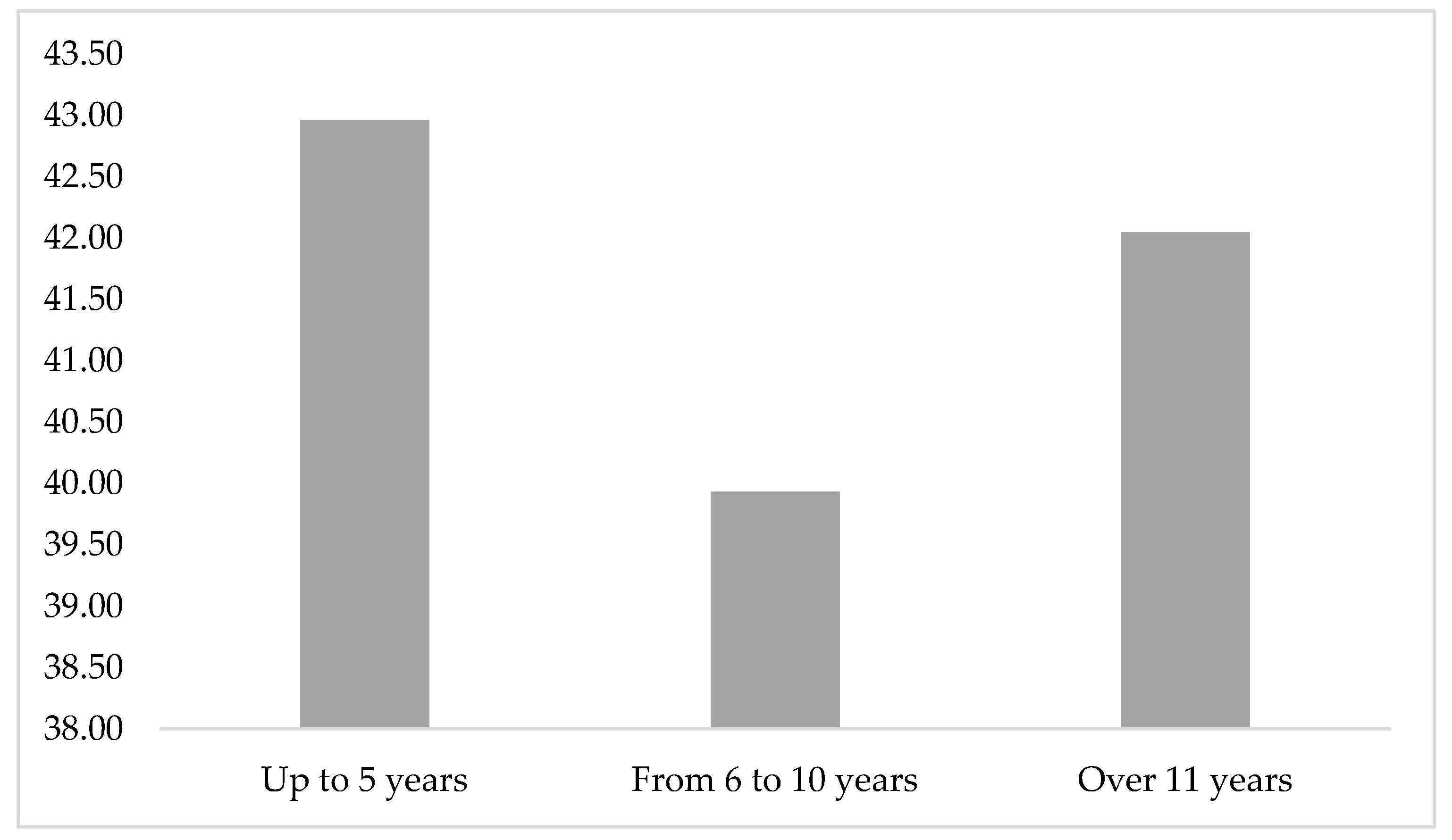

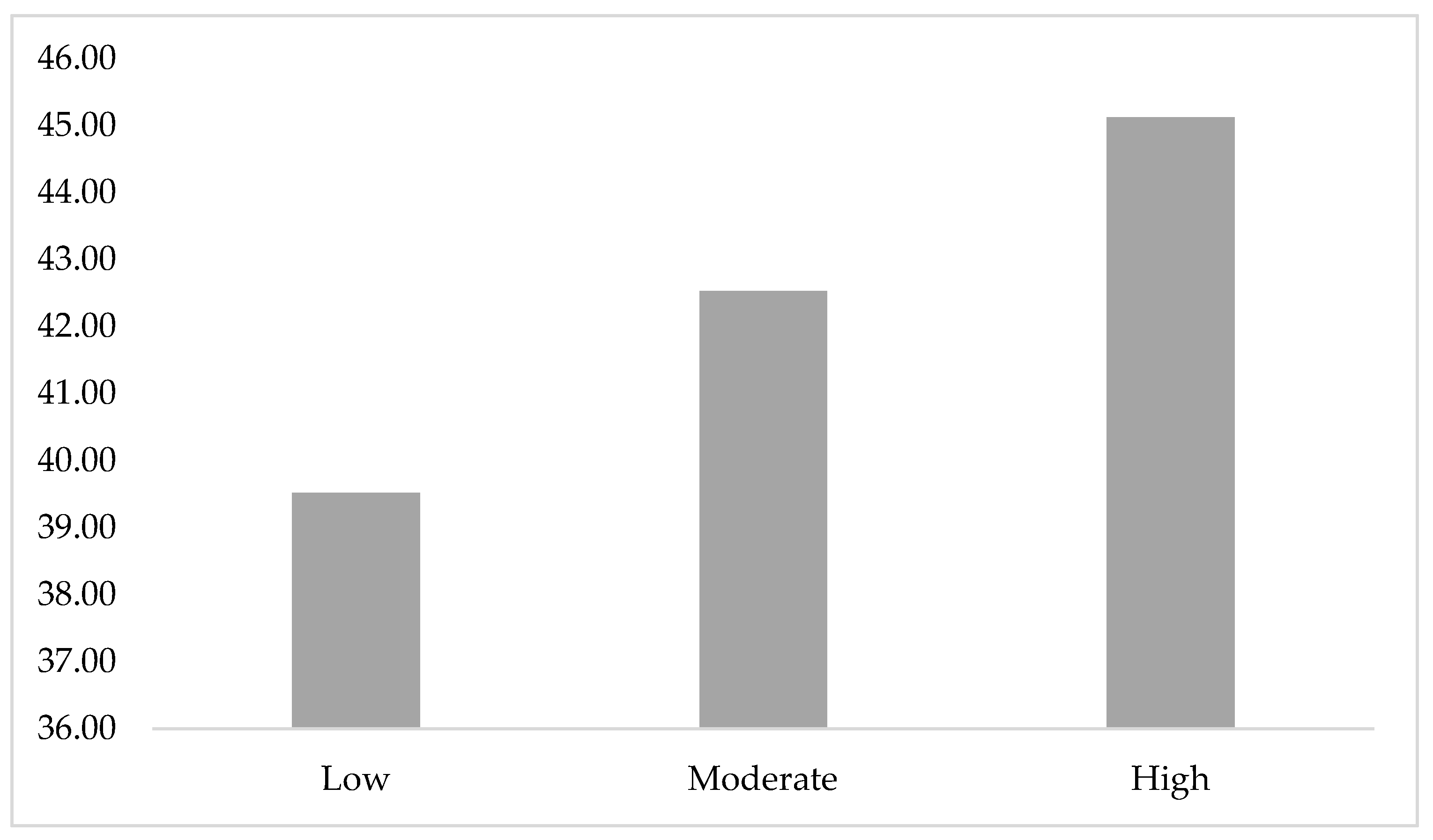

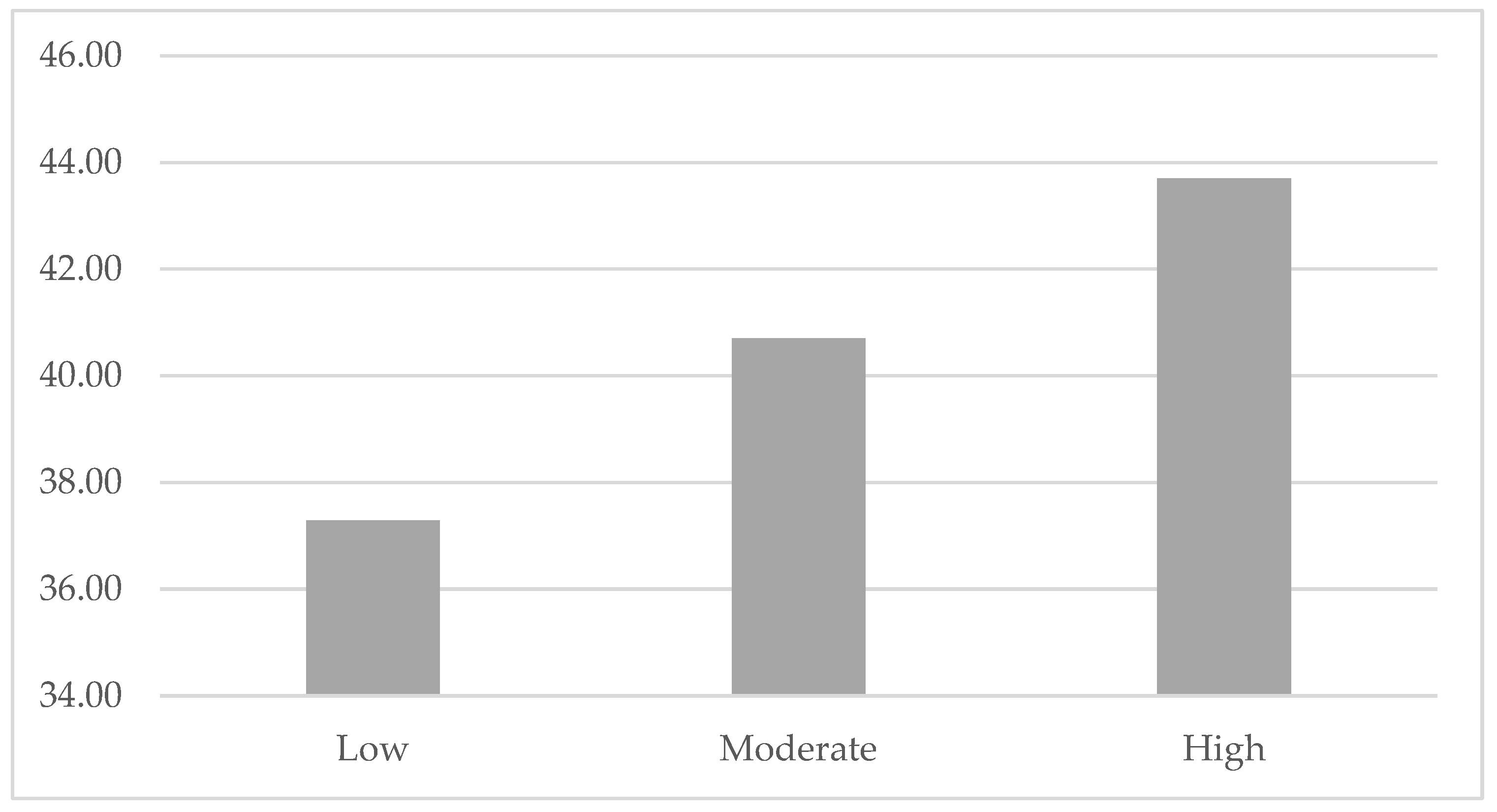

| Lengths of Entrepreneurial Experience | Levels of Monthly Income | Levels of Job Satisfaction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F test | 3.02 | 4.25 | 5.47 |

| p value | 0.056 | 0.019 | 0.006 |

| G1 M | 42.96 | 39.52 | 37.29 |

| G2 M | 39.93 | 42.53 | 40.70 |

| G3 M | 42.05 | 45.13 | 43.70 |

| G DIF | 1 > 2 | 1 < 2; 1 < 3 | 1 < 3; 2 < 3 |

| Indicators of Entrepreneurial Skills | General Self-Efficacy | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | I find it difficult to deal with stressful situations at work. | −0.468 * |

| 2. | I compare myself to others when I judge how successful I am in business. | 0.005 |

| 3. | I have clear beliefs and expectations about my work. | 0.515 * |

| 4. | Recognition from my colleagues serves as a confirmation that I am doing my job well. | 0.161 * |

| 5. | I sometimes panic when direct competition appears. | −0.249 * |

| 6. | I clearly understand and value myself. | 0.263 * |

| 7. | I have all the skills and habits to be a successful entrepreneur. | 0.475 * |

| 8. | I learn from bad business moves. | 0.295 * |

| β | S. E. | df | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I find it difficult to deal with stressful situations at work. | −0.265 | 0.147 | 3 | 3.251 | 0.030 * |

| I compare myself to others when I judge how successful I am in business. | 0.164 | 0.223 | 2 | 0.540 | 0.586 |

| I have clear beliefs and expectations about my work. | 0.272 | 0.177 | 1 | 2.354 | 0.131 |

| Recognition from my colleagues serves as a confirmation that I am doing my job well. | −0.172 | 0.198 | 3 | 0.750 | 0.528 |

| I sometimes panic when direct competition appears. | −0.092 | 0.210 | 2 | 0.191 | 0.827 |

| I clearly understand and value myself. | 0.257 | 0.235 | 2 | 1.200 | 0.310 |

| I have all the skills and habits to be a successful entrepreneur. | 0.216 | 0.173 | 2 | 1.569 | 0.218 |

| I learn from bad business moves. | 0.306 | 0.126 | 2 | 5.847 | 0.005 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ratković Njegovan, B.; Vukadinović, M.; Šiđanin, I.; Bunčić, S.; Njegovan, M. Optimistic Belief in One’s Own Capableness as a Factor of Entrepreneurial Sustainability: The Assessments of Self-Efficacy from the Perspective of Serbian Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912749

Ratković Njegovan B, Vukadinović M, Šiđanin I, Bunčić S, Njegovan M. Optimistic Belief in One’s Own Capableness as a Factor of Entrepreneurial Sustainability: The Assessments of Self-Efficacy from the Perspective of Serbian Entrepreneurs. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912749

Chicago/Turabian StyleRatković Njegovan, Biljana, Maja Vukadinović, Iva Šiđanin, Sonja Bunčić, and Milica Njegovan. 2022. "Optimistic Belief in One’s Own Capableness as a Factor of Entrepreneurial Sustainability: The Assessments of Self-Efficacy from the Perspective of Serbian Entrepreneurs" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912749

APA StyleRatković Njegovan, B., Vukadinović, M., Šiđanin, I., Bunčić, S., & Njegovan, M. (2022). Optimistic Belief in One’s Own Capableness as a Factor of Entrepreneurial Sustainability: The Assessments of Self-Efficacy from the Perspective of Serbian Entrepreneurs. Sustainability, 14(19), 12749. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912749