1. Introduction

The accelerated growth in information and communications technology (ICT) industry has become a landmark for economic development worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. The growth of ICT has been augmented by the widespread usage of mobile technologies and significant expansion in the digital market, transforming users’ expectations and government’s support. By highlighting such phenomena, ICT has paved the path for a financial paradigm shift in terms of service delivery. FinTech innovations have boomed in the last few years, facilitating secure, efficient, simple, and high-quality delivery of web-based banking services. According to Gai et al., 2018, FinTech is “a distinguishing taxonomy that mainly describes the financial technology sectors in a wide range of operations for enterprises or organizations, which mainly addresses the improvement of the service quality by using information technology (IT) applications” [

4]. There are various benefits of FinTech, for example, low-cost transaction fees, user-friendly and transparent service, enhanced service quality, and highly efficient financial solutions [

5,

6,

7]. As such, FinTech has flourished as a result of the need to meet users’ demands and of commercial organizations endeavoring to satisfy such demands and requirements [

6,

8].

FinTech has been implemented in different industry areas, for example, securities, insurance, and e-commerce payments [

9]. The recognition of FinTech rises as the fourth industrial revolution, or Industry 4.0, has triggered a significant shift in the financial systems. FinTech, for instance, facilitates financial practices such as enterprise business, trading, and e-services offered to retail consumers [

8]. The latest proliferation of the m-payment industry led by innovative FinTech payments services such as Samsung Pay and Apple Pay, etc. is evidence that it is the most vital and fastest developing industry from customers’ viewpoint [

8,

10]. Such services, provided by non-financial institutions, are growing at a great pace since they allow customers to simply enter their passwords, PINs, and/or biometric authentications without the need to install other complicated add-ons [

8,

10]. According to Senyo and Osabutey [

11], FinTech services are strongly considered to be underlying game-changers in strengthening financial inclusion. At present, there is a range of FinTech services, including insurance, digital payments, assets management, online banking, online financing and lending, crowdfunding, etc. accessible through various organizations, credit card companies’ IT service providers, and banks.

Technological tools (e.g., FinTech services and applications) have been implemented among public and private organizations in their efforts to communicate improved experiences to their employees and customers [

12]. However, Al-Okaily et al. [

13] have stated that there is a need to scrutinize these IT tools, such that their positive effect on users’ experience could be achieved. The impact of these technologies’ characteristics on users’ experience should also be investigated, thus the acceptance and adoption of such technologies. Therefore, great attention needs to be paid when designing and developing such IT.

Yet, a large group of users has demonstrated a reluctance to adopt FinTech services [

11,

14]. Individuals may have critical concerns about using online technologies for financial transactions, much of these concerns illuminate users’ perceptions of security and privacy risks [

15,

16], the virtual nature of transactions, required skills and education, degree of ease, and accessibility of FinTech services [

11]. Other researchers have highlighted users’ concerns regarding the available infrastructure including personal computers, internet access, internet-enabled devices, etc., uncertainty levels; the services effectiveness, and the required IT skills for transferring online [

17]. Therefore, it becomes of vital importance for policymakers, practitioners, and service providers to understand the antecedents that could facilitate or inhibit the acceptance and adoption of FinTech, which contributes to strategy formulation, improvement of the take-up of FinTech services, and the deepening of financial inclusion.

The acceptance and adoption of FinTech by individuals differs from one citizen’s group to another, from one social context to another, and from one cultural background to another [

18]. In Jordan, the number of internet users rose from 48.4% to 103.5% of the population between 2015 and 2020 [

19] which created an opportunity for Jordanian financial institutions to expand to a wider customer base of their online services. However, despite the relatively well-managed and advanced financial systems and the vast amount of investments and different resources that have been estimated in this vein by all financial service providers including banks in Jordan [

20], FinTech is still a relatively novel phenomenon in the Jordanian context and its acceptance and use by the users is stated to be very low [

21,

22,

23]. For instance, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) indicated in “Digital Finance Country Report—Jordan” (2018), that the ownership rate of mobile phones in Jordan is 92.1 percent, with 76.5 percent of adults holding smartphones. According to the report, this has so far only translated into 1.4 percent of adults using internet banking (IB) and 2.1 percent using m-banking services, so financial service providers are required to improve the usability and quality of their services. In addition, in 2020, the share of adult inhabitants having one or more mobile wallets was only 11.1% [

20]. This reality implies that FinTech services and applications in Jordan are still innovative and the usage rates lag very far behind in comparison to counterparties in other countries. Such low usage rates are upsetting for financial institutions [

22,

23,

24]. In addition, it is also stereotyped that in Jordanian culture a lot of the population prefers the classic/physical payment methods to conduct financial transactions which raises a concern regarding the low usage rates of FinTech [

24].

Without knowing the influencing factors, service providers are probably going to continue struggling, wasting resources, effort, and time. Furthermore, people are required to be aware of FinTech services and applications and feel secure and satisfied with utilizing FinTech as such technology is completely novel to them. Therefore, further studies are needed to understand the antecedents affecting the adoption and use of FinTech by users in Jordan aiming to develop strategies that will ensure the successful implementation and use of FinTech services, particularly in crisis times. Although m-payment/e-payment services, as forms of FinTech services, have been widely investigated in developed countries as a result of the technological evolution in payment methods, there has not been enough research carried out on the adoption of these technologies in developing countries in general, and Jordan in particular. According to the authors’ knowledge, this study is considered the first empirical research which investigates the adoption intentions of FinTech services among Jordanian citizens in the post-COVID-19 era. Thus, the current research presents an effort to fill the gap mentioned above and determine the critical factors that affect the acceptance and use of FinTech in the Arab context, Jordan in particular. Hence, this study has introduced the contextual foundation for replication and comparison within other Arab contexts. Accordingly, this becomes a significant contribution to the IT/IS literature and it encourages other researchers to conduct further research on the acceptance and use of FinTech at the regional level.

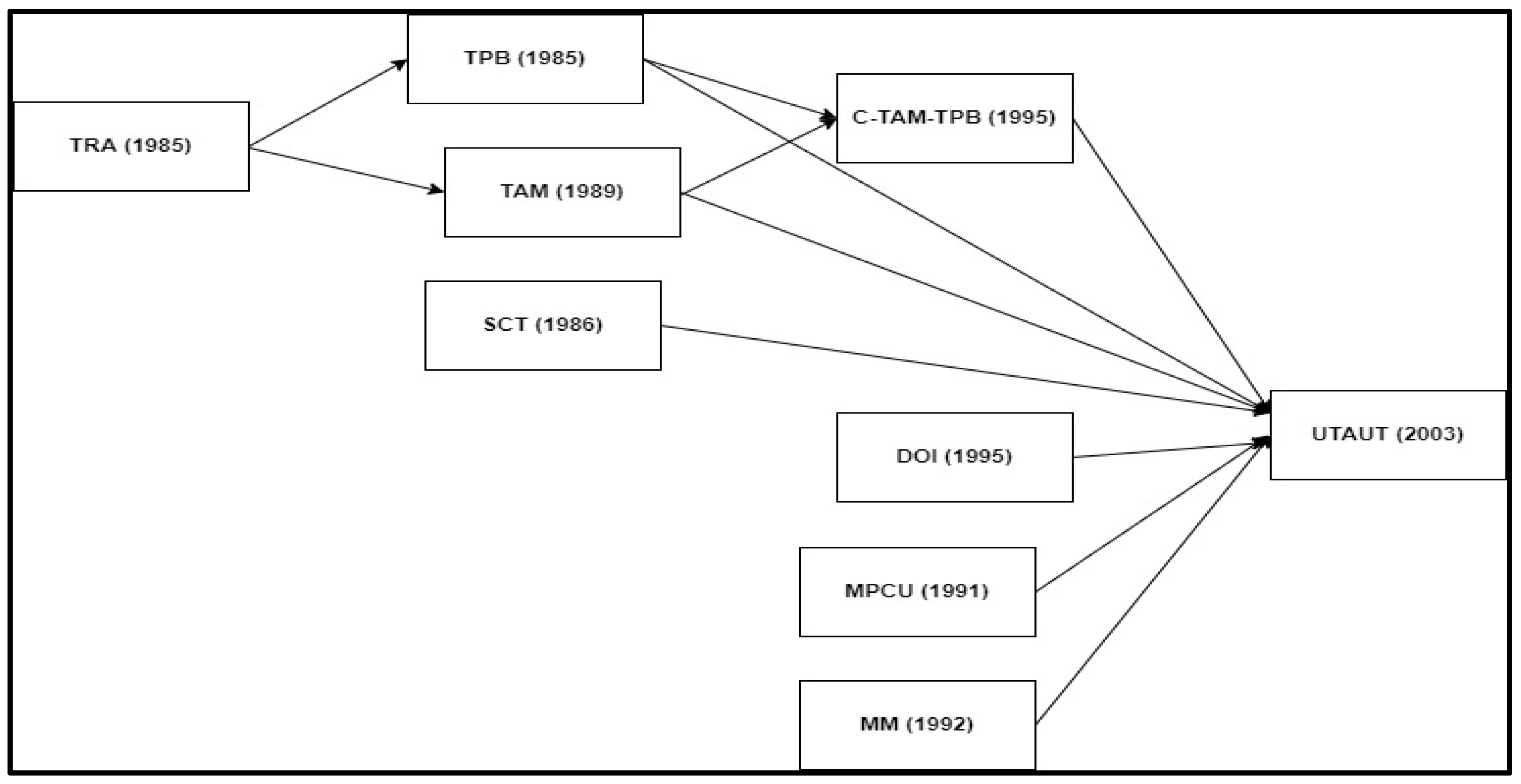

Different well-known theoretical models have been developed to understand the relationships between users’ beliefs and behavioral intentions (BI) to accept and use new technologies. From the perspective of social psychology, the theory of reasoned action (TRA), the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the social cognitive theory (SCT), the motivational model, technology acceptance models (TAM), the combination of TAM and TPB constructs, and diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory are only a few of the key theoretical approaches that have led the path in analysis and conclusions [

18]. As a result of reviewing and synthesizing eight previous theoretical models of IT/IS acceptance and use, Venkatesh et al., 2003 [

25] introduced the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) (see

Figure 1).

UTAUT has been established to be a valid theoretical research tool for predicting individuals’ usage behavior by emphasizing the salient role of PE in explaining IT/IS acceptance and use [

26,

27]. Hence, UTAUT becomes one of the most widely applied theories due to its robustness and parsimony [

18]. It was also confirmed to be superior to other prevalent competing theories [

28,

29].

Applications, extensions, and integrations of this model have enabled many scholars to understand IT/IS acceptance and use systematic theorizing, despite the extensive replications; an investigation of the salient constructs that affect context-based user IT usage is therefore required [

18]. In addition, scholars in the field of information systems debate over whether the constructs of UTAUT are adequate to predict users’ acceptance of innovative IT in a voluntary context, as initial UTAUT research focused on organizational context which limits UTAUT’s explanatory power [

18].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, borders, malls, financial institutions, and even small shops closed to reduce any additional spread of the virus in healthcare and public settings. FinTech services allow citizens and organizations to access, perform and sustain financial transactions, mainly due to the measures, guidelines, and strategies that many governments worldwide have enforced (e.g., social distancing and staying home) to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 infection. As a result, FinTech applications have accelerated at a swift speed [

10], offering a significant opportunity for FinTech service providers. Yet, the situation has considerably changed; under normal conditions, people still desire to do traditional shopping activities and perform financial transactions face-to-face/physically [

6]. Due to the health crisis, such types of transactions are required to be transformed online, and FinTech applications have become the main technology to sustain risk-free and smooth financial transactions. Yet, earlier literature has not investigated the impact of COVID-19 on the significant change to users’ FinTech behavior after the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition, in an ongoing state of health crisis state that has persisted for more than two years, people realize how beneficial FinTech is in sustaining a normal life. Individuals may become familiar with the suitability of this technology and continue to utilize it after the pandemic times. FinTech applications are becoming competitive as they help to maintain existing users and attract potential ones. They are needed to determine the characteristics that influence users’ intention to use FinTech services, as well as leverage the competitive advantage. Therefore, the current study identifies the important factors that influence behavioral intentions toward FinTech services after the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the consequences of FinTech adoption have not yet been examined. If users feel satisfied with FinTech services, they are likely to keep utilizing them for a long period and become loyal [

30]. The current study investigated the e-Loyalty of a user as a consequence of getting a satisfactory financial service experience throughout forced situations, i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic. The research findings may highlight and explain a user’s positive behavior toward using the FinTech services after crisis times.

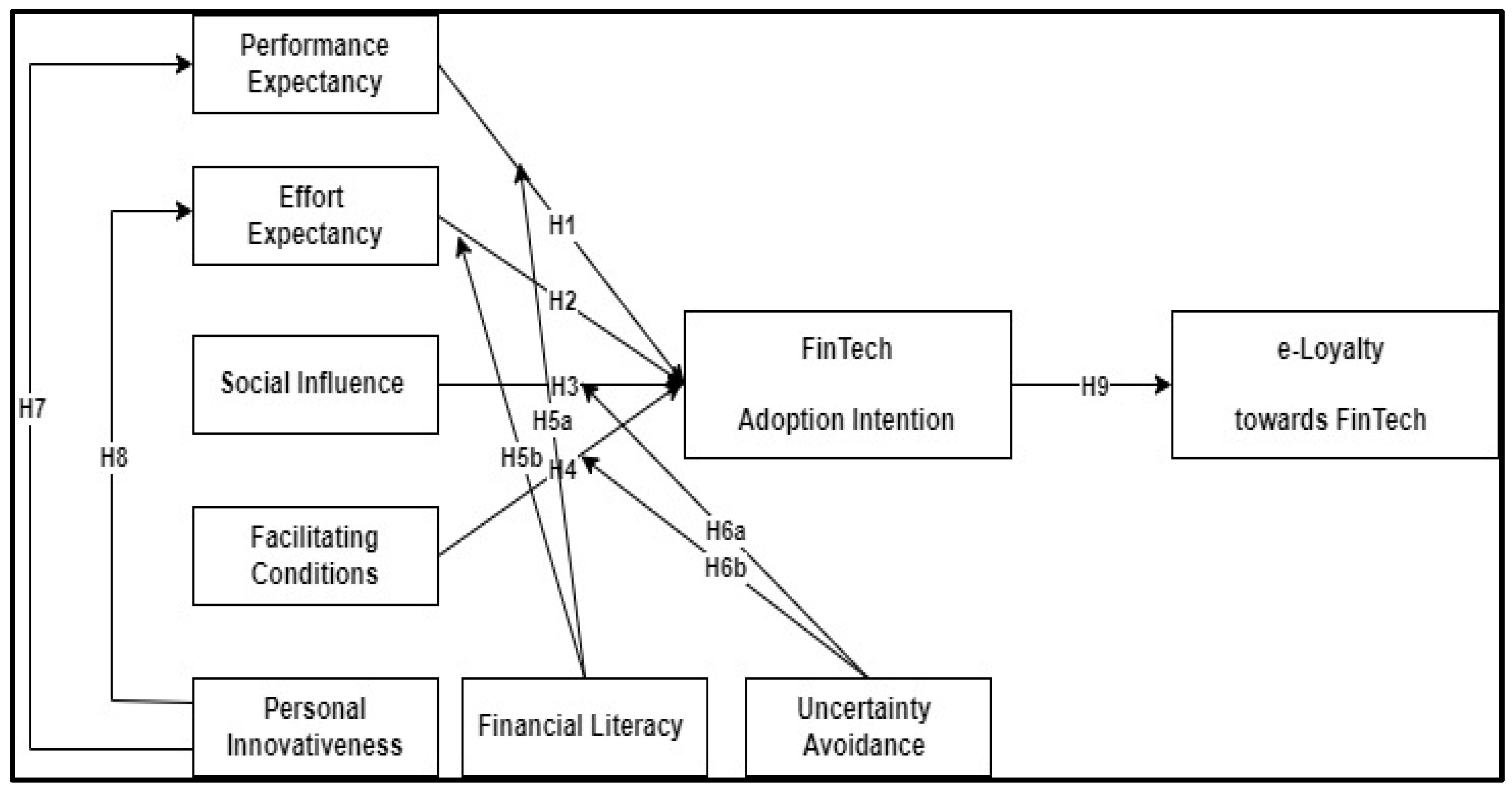

Moreover, to investigate the acceptance of FinTech, other factors are considered important such as the PI, FL, and UA in the current research context. By modifying the UTAUT model to take account of those factors, a more comprehensive study model of user IT acceptance in the context of FinTech will be introduced. Without a doubt, FL has been deemed a significant factor in user reluctance to perform financial transactions using FinTech [

31]. This is because the individuals are principally responsible for their financial transactions and hence their decisions will be controlled by issues of knowledge and skills. Hwang and Lee (2012) [

32] stated that though users’ confidence in the technology is strong, this confidence could be affected in high UA cultures owing to the intangibility and ambiguous consequences of utilizing such technology. Consequently, adding UA will complement the original constructs of the UTAUT and is likely to provide a better explanation of users’ adoption of FinTech in Jordan. The rationale behind incorporating UA in UTAUT is the direction of managerial attention to cultural challenges and to provide a trustworthy virtual environment that allows its users to make full use of FinTech. Furthermore, a review of more recent literature suggests other factors relevant to the acceptance and use of innovative technologies (e.g., FinTech). In the current research, the authors integrated the PI within the UTAUT as an antecedent of users’ behavioral intention. The rationale behind integrating PI is based on the fact that the level of user’s speed of adopting new technology compared to others in the social system will develop positive perceptions regarding technology acceptance and use [

33].

In addition, the majority of the IT/IS acceptance models, and particularly UTAUT, have not been widely examined in developing countries in general and Jordan in particular. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, there is no single research that has addressed the relationship between users’ intention and e-Loyalty of FinTech in Jordan, particularly in the post-COVID-19 period. Furthermore, the proposed constructs and relationships have not received any attention from previous research in the Jordanian setting. Thus, the current research aims to bridge this gap by modifying the UTAUT to integrate those constructs, namely PI, FL, and UA.

Generally, the current research would be useful for FinTech service providers and policymakers to illustrate the relatively low current rates of use of FinTech in Jordan after the times of crisis, which could contribute to the formulation of strategies to promote the acceptance of FinTech by Jordanian users, where FinTech is still deemed an innovation. Over the last few years, Jordan has developed a world-class FinTech service. The government in Jordan has made the development of e-government systems and services a pivotal goal for the country’s future. FinTech services and applications (e.g., m-wallet and m-payment) are at the core of that development. One major objective is to move toward financial inclusion [

20,

34], which aims to introduce official financial services for eliminated and underprivileged groups instead of unofficial alternatives, especially for citizens and residents living in rural areas without bank accounts. This would enable these groups to make electronic payments using FinTech services through their internet-enabled devices such as mobile phones [

34,

35]. Understanding the experiences, issues, challenges and lessons encountered by Jordanian users during this implementation can benefit service providers and professionals worldwide, particularly those in developing countries aspiring to enhance and develop FinTech services, and especially those in the Middle East region. For this reason, the authors carried out an empirical study identifying the key factors that affect the acceptance, use, and e-Loyalty of FinTech services in Jordan.

This article also contributes to the research related to theoretical models of IT/IS acceptance and use which have been suggested to be extended to new contexts by scholars (e.g., [

18]) and particularly to the applicability and generalizability of the UTAUT in new contexts (FinTech after the COVID-19 pandemic), new user groups (customers/end users) and new cultural settings (Jordan), something which is a crucial step in advancing a theory [

36]. Considering the fact that Jordan is a country with citizens who are varied in terms of their education, cultural backgrounds, and income, these characteristics will offer interesting dimensions to the research work and introduce unique insights into the nature of variables that are significant to financial institutes in such environments.

The structure of the article is organized as follows. The first section provides a study model and hypothesis development. The second section proposes the research methodology implemented in this study. The third section shows the findings based on the statistical analysis. The fourth section discusses the results. Finally, further potential research directions are presented, and research limitations are outlined.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

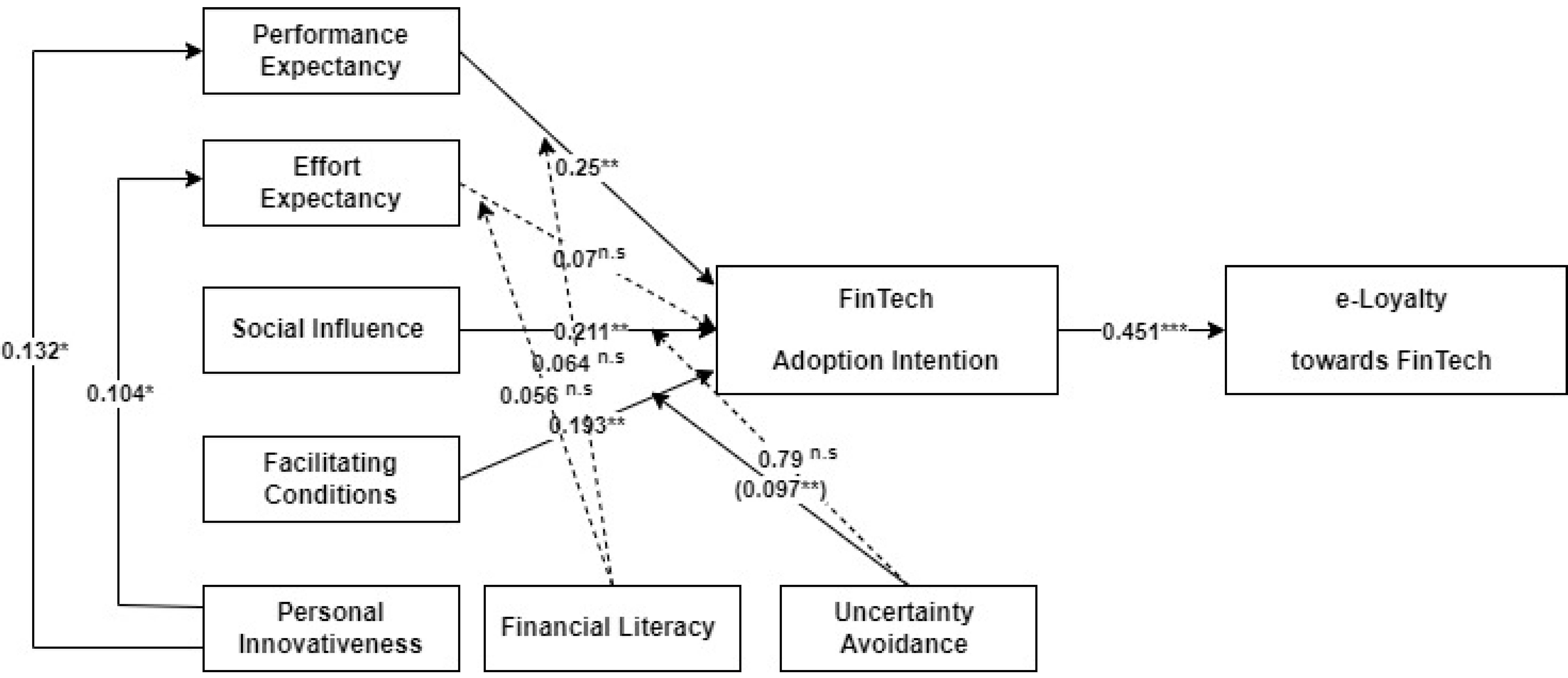

The main aim of the current research was to extend the UTAUT by integrating FL, UA, PI, and e-Loyalty factors in order to identify the variables that influence users’ intentions toward using FinTech in Jordan during and beyond the COVID-19 crisis. The findings in the current study empirically and theoretically support the ability of the UTAUT model to be a suitable theoretical framework to offer a better understanding of the user’s acceptance of FinTech. Generally, the results show that FinTech is well accepted in Jordan. Most of the direct associations between the suggested constructs and behavioral intentions were revealed to be statistically significant except for the association between EE and BI. In addition, the findings of this study show that users’ intentions to use FinTech systems and applications were found to be significantly influenced by PE, SI, and FC, while EE did not play a salient role in affecting BI to use the FinTech. The findings also found that PI was found to be a significant determinant of both PE and EE. Intentions to utilize FinTech with the cumulative contribution of the factors proposed in the study model can lead to users’ e-Loyalty, and the user will continue to use the technology after the COVID-19 pandemic. The new normal behavior will be established [

6], and both managers and academic researchers are predicting that this type of behavior will develop adequate strategies.

In this study, PE was found to be one of the significant determinants within the proposed model. This study’s results confirm what has been suggested by previous studies [

35,

49,

97,

98]. Thus, when the user of FinTech finds the technology to be beneficial then they are more expected to have better perceptions and intentions towards using it. Consequently, practitioners and developers need to enhance the quality of their FinTech applications based on user suggestions and recommendations in order to motivate more users and satisfy their needs and expectations. To attain this, policymakers and service providers should offer a usage manual that provides detailed instructions and information regarding the advantages of FinTech applications and services such as allowing individuals to perform financial transactions from anywhere and at any time while they have internet-enabled devices. Also, as PE was confirmed to have a significant effect on BI to adopt FinTech services, the service providers should give thought to upgrading the existing FinTech applications and services to offer greater performance to the customers. That is, financial institutions should invest more in domains that affect the users most, for example, taking into consideration functions to optimize financial transactions and swift payments.

Surprisingly, EE has been found in the current research to be an insignificant predictor of users’ intention toward using FinTech. While this result is inconsistent with prior conclusions [

25] it is consistent with those of [

47,

99,

100]. A possible explanation is that difficulty in utilizing web-based services and applications is becoming less of a concern for the users as such technology becomes more user-friendly. Thus, the users will mainly utilize those applications and services because of their perceived usefulness (or performance expectancy) rather than their ease of use (or effort expectancy). Consequently, it is recommended that application developers need to design more user-friendly FinTech interfaces in order to attract individuals with less IT skills to accept and adopt FinTech.

Even though technology users are not influenced by reference groups but by individual needs in voluntary contexts [

25], the findings of this research indicate that SI has a significant positive impact on users’ intentions which is similar to what has been suggested by prior literature in the area of information systems (e.g., [

17,

41,

101,

102,

103]). In this study context, it is recommended that practitioners and service providers be required to encourage earlier adopters of FinTech to contribute to the promotion of this technology to other people. This is important in Jordanian culture which has high degrees of power distance, uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, and femininity. Generally, in such contexts, individuals may be influenced by positive WoM from their colleagues, peers, friends, and important others. In an effort to attract additional users, the providers of FinTech services are also recommended to increase the use of social media channels (e.g., Facebook), SMS messages via mobiles, and e-mails as well as traditional media channels (e.g., TV and newspapers). This, in turn, will influence individuals’ decisions to accept and use FinTech.

Earlier literature has suggested that FC plays a significant role in behavioral intentions toward using technology [

7,

53,

54]. Thus, FinTech service providers are required to invest more in IT infrastructure and also recommended to offer all facilitating conditions for their users such as offering help service centers to enhance users’ IT skills and their ability to use FinTech applications. By doing so, people are more likely to have positive inclinations to accept and use FinTech.

While the moderating relationships for FL were rejected (H5.a and H5.b), further investigation of its direct relationship with behavioral intentions shows a negative effect. This finding could suggest that Jordanian users of FinTech with higher levels of FL have an inverse association with intentions to adopt and use this technology in Jordan. This is a peculiar result showing inconsistency with the findings from earlier studies e.g., [

31], which revealed a positive effect of FL on FinTech adoption intentions. This inverse relationship could be explained by the way in which, in Jordan, FinTech may play a role in significantly attaining a level of financial inclusion in which individuals with lower FL are also able to utilize FinTech to complete financial transactions in ways which were, in the past, inaccessible. This may also mean that Jordanian people with higher FL do not conceive FinTech as a valuable tool to complete their financial transactions, as those users may have high accessibility to conventional financial tools and facilities. To attract early adopters of FinTech, those with higher educational levels and multiple financial institutions connections need to be targeted. Yet, it is also possible for this group to have an adequate level of financial literacy, but be less inclined to trust the new service providers of FinTech. This means more effort is essential to persuade and build trust from the perspective of this user segment.

The moderating impact of the cultural dimension (i.e., UA) was also tested and this led to the rejection of H6.a, because the suggested interaction did not significantly affect the behavioral intention of the study sample. This finding suggests that espoused cultural values of UA did not play a vital role in moderating the hypothesized association. This finding is similar to other researchers’ conclusions, for example [

72]; which confirmed that culture has no significant impact as a moderating factor. Also, empirical results from the current study found that, for FinTech users with higher levels of UA, the impact of FC on FinTech usage intentions decreases. While contradictory results have been confirmed by scholars (e.g., [

104]), their findings indicate that users are more likely to accept innovative technology that is easier to be used in cultures with high levels of UA to minimize unwanted outcomes [

105]. Future research could conduct further investigations of the two moderating factors (FL and UA) relationships with other factors, such as their direct relationship with the BI to adopt FinTech.

PI is established as a critical antecedent variable. It is seen that PI has a direct relationship with both PE and EE (H7 and H8). This result confirms what has been found in previous studies [

30,

75], where the role of PI is established as an important factor from the perspective of IT users. The users of new technologies (e.g., FinTech) considered them innovative by nature, however, this result highlights the possibility of segmenting the market for innovative technologies and applications based on the innovative traits of the users. Next, the current study investigated the extended variables affecting the behavioral intention towards FinTech, enhancing the e-Loyalty to these services. Original constructs of UTAUT (i.e., PE, EE, SI, and FC) were added to FL, UA, and PI to examine their impacts on users’ behavioral intention to use FinTech which is suggested as an antecedent of e-Loyalty. These factors could contribute to intentions to adopt FinTech post-COVID-19, and increase e-Loyalty.

In this study context, the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic introduce a leverage opportunity to boost the improvements of FinTech and users’ intentions to adopt such services in the post-COVID-19 era. Users will become loyal to FinTech as a result of their behavioral intentions to use these services, services that they were required to adopt due to the contingency circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. The users’ intentions come from factors that have been validated by this study to be PE, EE, SI, FC, UA, and PI. Hence, the crisis circumstances are a good lever to access FinTech services, assisting users to realize the value of FinTech. Users who accept and use FinTech become loyal to it, as long as the abovementioned variables are still maintained and guaranteed as expected.