Abstract

Small to medium-sized enterprises suffer from loss of competitive advantage, low productivity, and poor performance because of inadequate competencies. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to examine the effect of selected motivational dimensions (i.e., self-improvement, self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, and the need for achievement) on entrepreneurial competency among micro-entrepreneurs. We used a cross-sectional design and collected quantitative data from 403 micro-entrepreneurs in Malaysia using random sampling. SEM-PLS was used for data analysis. The findings revealed that self-confidence, openness to change, and pull factors positively influenced entrepreneurial competencies. Moreover, there was a positive effect of self-confidence, pull factors, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial competency on enterprise sustainability performance. Furthermore, entrepreneurial competencies significantly mediated the effect of self-confidence, openness to change, and pull factors on enterprise sustainability performance. Apart from extending the lens of a resource-based view, this study enriches enterprise sustainability literature from emerging nations’ perspective. Policymakers can strengthen their programs and policies to improve the entrepreneurial competencies of micro-entrepreneurs and their business sustainability.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial activities are perceived as a crucial driver for economic development and expansion [1]. Particularly, entrepreneurial activities by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) contribute to the socio-economic development of every country [2]. They are crucial for regional advancement and sustainable development in comparison to their larger counterparts [3]. According to Alshebami [4], SMEs drive economic growth by creating job opportunities, mitigating poverty, and improving the standard of living of residents. Micro and small-sized enterprises, on the other hand, contribute to economic development through an increase in household income and provision of employment [5]. Micro, small, and medium enterprises play a key role in growing developing countries’ economies [6]. In Malaysia, 75 percent of SMEs contribute to the national economy [7]. Specifically, informal micro-enterprises in Malaysia generate income that contributes to the gross domestic product and employment [8].

In the adverse post-pandemic world, psychological characteristics act as key factors for directing individual behavior towards entrepreneurial activities [4]. In fact, sustainable entrepreneurship requires individuals with unique competencies and traits that can determine organizational success [9]. According to Tehseen et al. [2], entrepreneurial competencies can ensure the growth of SMEs. In the case of small and micro enterprises, they can improve the performance and continuity when the owner(s) and employees acquire certain knowledge, skills, and entrepreneurial traits to conduct their business activities [10]. Mitchelmore and Rowley [11] defined entrepreneurial competencies as individual traits that succeed entrepreneurship. These competencies can be used to make a business successful with sustainable competitive advantage [12]. In Malaysia, relevant competencies strongly determine SME success [13], and hence are expected to positively influence micro-enterprise performance, in the present context [14].

Building competencies is one of the entrepreneurial stages. It is a cognitive and motivational factor that reflects a person’s ability and willingness to act [15]. Entrepreneurial motivation is a salient predictor of entrepreneurial performance among small enterprises [16]. Entrepreneurs accomplish their business ownership through behavioral patterns indirectly; wherein, motivation strongly influences the success of a business, particularly in the context of micro-entrepreneurship [17]. A few groups of researchers highlight that those entrepreneurial motivations can affect entrepreneurial intention [18,19] and other entrepreneurial outcomes [20]. In particular, Eijdenberg and Masurel [21] argue that research attention has been directed to entrepreneurship motivation.

From an emerging economy perspective, our vision is that entrepreneurial motivation can enrich an entrepreneur’s behavioral pattern and its subsequent impact on business performance [17]. Unfortunately, the human motivator in entrepreneurship research has received insufficient consideration [15] in a non-Western context [21], which reflects a gap in the existing literature. Moreover, although successful SMEs can flourish in the socio-economic condition, it is imperative to understand the competencies among entrepreneurs [2]. In Malaysia, SMEs suffer from loss of competitive advantage, low productivity, and poor performance because of inadequate competencies [2,7,12]. A recent study highlighted that the impact of relevant competencies on enterprise sustainability performance remains underexplored [22]. This further establishes the rationale for this study that is the most timely and significant. Additionally, Joddar [23] noted that the sustainability of microenterprises facing a competitive market is a major challenge, thanks to globalization, coupled with global changes in technology and the market integration of economy. In line with this, Masama and Bruwer [24] found that small, medium, and micro-enterprises have high failure rates, which indicates a strong need for research to ascertain the factors that influence micro-enterprise sustainability.

Deducing from the aforesaid, we strongly argue that survival and sustainable performance are pressing issues globally and locally, wherein entrepreneurial motivation and competencies could be the missing link. We do acknowledge that earlier attempts to examine motivation, competency, and performance separately exist in related previous studies. For example, Eijdenberg and Masurel [21] focused solely on push and pull factors to investigate entrepreneurial motivation in the least developed countries. In a local context, Tehseen et al. [2] studied entrepreneurial competencies among entrepreneurs in Malaysian retail SMEs to present a novel theoretical framework. Empirically, Al Mamun et al. [22] revealed the effect of selected entrepreneurial traits (i.e., locus of control and vision) on competency, performance, and enterprise sustainability. However, this study differed from existing literature by examining the effect of multiple motivational dimensions on entrepreneurial competency and sustainability performance in a single holistic framework, thereby offering a nuanced understanding of the interplay between competencies, motivational dimensions, and sustainability performance. Moreover, the present study extends the related conceptual investigations [2,12] by forwarding empirical evidence portraying the interactions between motivational dimensions, competencies, and sustainability performance. Furthermore, drawing data from Malaysia, we address the gap of non-western studies [21] by adding the emerging economy’s perspective to the literature. Based on the above, the research question for this study could be worded as: How the diverse motivational dimensions effect entrepreneurial competencies and sustainability performance among micro-enterprises? In order to address the research question, the primary goal of this study was to examine the effect of entrepreneurial motivation dimensions on competency and sustainability performance among micro-entrepreneurs, using Malaysia as a data source.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Context of Study

Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises are the life blood of national economy globally, thanks to their potential to support fundamental socio-economic objectives, such as creation of employment opportunities, distribution of wealth, as well as alleviation of poverty [24]. According to Joddar [23], the sustainability of microenterprises could reduce the vulnerability of rural masses. Malaysia represents an emerging economy, wherein SMEs comprise 98.5% of all business entities [25]. According to Zainol et al. [8], micro-enterprises act as a platform to enhance the entrepreneurs’ skills and have significant contribution towards the Malaysian economy and gross domestic product through generation employment, income, and community development. Research has highlighted that SMEs in Malaysia fail majorly due to various challenges such as their inability to sustain themselves, either because of the lack of the managerial and competency skills, or due to having less resources, etc. [2,7,12].

In Malaysia, SMEs have been categorized into micro, small, and medium enterprises based on annual sales turnover and full-time employees [25]. A micro enterprise is defined as having fewer than 5 employees. Small enterprises, on the other hand, could have between 5 and 75 employees in case of manufacturing and between 5 and less than 30 employees for other sectors. As for medium enterprises, they may accommodate between 75 employees and 200 employees in the case of manufacturing and between 30 and 75 employees for other sectors. In term of sales turnover, micro enterprises are defined as earning less than RM 300,000 annually. Small enterprises, on the other hand, are defined as earning between RM 300,000 and less than RM 15 million in case of manufacturing and between RM 300,000 and less than RM 3 million for other sectors. Finally, medium enterprises could report a sales turnover of between RM 15 million and RM 50 million annually for the manufacturing sector and between RM 3 million and RM 20 million for other sectors. We focused on micro-entrepreneurs who fit into the definition of micro enterprises. Malaysian SMEs are majorly engaged in mining and quarrying, agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and services. In terms of GDP, SMEs contributions totals at 38.9%. As for employment, 48.4% of Malaysia’s employments are among SMEs [25].

2.2. Resource-Based View

From a resource-based perspective, it is crucial to understand how a firm’s competitive advantage is gained [26]. According to the resource-based theory, competitive advantages are derived from rare, valuable, and inimitable resources that enable organizations to outperform their major competitors [10,26,27]. In micro-enterprises, this process is presumed to depend on the entrepreneurs’ ability to acquire, develop, and use resources [12,26]. As a result of being individual-specific, RBV considers entrepreneurial competencies as intangible unique resources that give rise to an organization’s competitive advantage sustainably [12]. RBV, thus, supports the possible effect of entrepreneurial competencies on sustainable competitive advantage. However, it is important to ascertain motivators that facilitate the formation and development of competencies. Hence, based on Murnieks et al. [28], we argue that a nuanced understanding of what motivates entrepreneurs through the RBV lens is immensely important. Moreover, when major transformation occurs due to natural and social constraints, valuable resources may not guarantee a strong competitive edge. Therefore, firms need to evaluate choices regarding allocation and utilization of unique resources to achieve corporate, social, and environmental performance [26,29]. As entrepreneurial competencies are given attention, entrepreneurial motivations such as self-improvement, self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, and need for achievement are required to develop an enterprise sustainability. Based on the above, we apply RBV to examine the influence of entrepreneurial motivations on competency and enterprise sustainability among micro-entrepreneurs, using data from Malaysia.

2.3. Selecting Motivational Components

Entrepreneurial motivation refers to the beliefs and expectations in regard to personal outcomes of pursuing entrepreneurship [18,19]. Entrepreneurial motivation is the goal and objective entrepreneurs seek to accomplish through business ownership [17]. Literature of entrepreneurial motivation includes an individual’s need for achievement, locus of control, desire for independence, vision, passion, goal setting, self-efficacy, and self-drive [15].

Eijdenberg and Masurel [21] categorized “pull” and “push” factors as entrepreneurial motivators. Levesque, Shepherd, and Douglas [30] stressed that entrepreneurial motivation is strongly associated with age. In addition, factors such as sex, age, and level of education can influence entrepreneurship engagement [31]. Entrepreneurs are motivated by a reward structure where an entrepreneurial initiation focuses on the entrepreneurship’s, usefulness, utility, or desirability [32]. Campbell [33] pointed out that expected net present economic benefits in comparison to the expected gains from waged labour are the key motivator of entrepreneurship. When the anticipated benefits outweigh the employment wages, individuals can take part in entrepreneurship [34].

As the present study focused on low-income entrepreneurs, their unique traits should be given attention instead of their actions [35]. The following entrepreneurial motivational components were chosen because entrepreneurship is encouraged by an individual’s cognitive and motivational factors, ability, and willingness to act [15]. Moreover, Murnieks et al. [28] highlighted that the majority of entrepreneurial motivation studies emphasized on the role of endogenous factors such as self-regulatory or affective constructs. Therefore, the present study classifies self-improvement, self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, and need for achievement as entrepreneurial motivations that are expected to influence entrepreneurial competency and enterprise sustainability.

2.4. Self-Improvement and Entrepreneurial Competency

Self-improvement illustrates the reasons for running a new business that is self-directed [36]. Competency, on the other side, refers to a specific set of individual-specific traits that help achieve a task [11,37]. According to Anoke et al. [38], self-improvement covers activities that improve awareness, identify capabilities, develop talents and potential that help in building human capital, escalate employment opportunities, and drive entrepreneurial intent. Theoretically, RBV supports the relationship between entrepreneurial competency and self-improvement. Entrepreneurial competency is an individual trait that instigates specific capabilities to achieve competitive advantage [26]. According to Zaripova et al. [39], project-technical competency can be measured by the degree of self-identity, relevant knowledge, abilities, skills, and self-improvement motives. Komelina et al. [40] noted that self-improvement can influence the development of economic competencies and character traits that capture social, economic, professional, and informational orientation. In fact, competency promotes the integration of knowledge, self-organization, self-improvement, personal reflection, and self-development [41]. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Self-improvement positively and significantly affectsentrepreneurial competency.

2.5. Self-Improvement and Enterprise Sustainability

Enterprise sustainability refers to the stakeholder-focused enterprise systems that address the integrated aspects of business performance over a period under the constraints set by both society and environment [42]. As supported by RBV, business managers with valuable knowledge, skills, beliefs, and capabilities can facilitate firm performance [12,26]. Self-improvement helps firms to achieve economic, social, and environmental performance [29]. Porath and Bateman [43] identified self-improvement as an opportunity for gaining higher education to improve performance. Zaripova et al. [39] reported that the aspiration for self-improvement, self-realization, and awareness can enhance professional activities through education and self-development. Self-improvement allows individuals to perform professional, political, social, economic, scientific, psychological, pedagogical, and methodical activities [40]. In Malaysian SMEs, Dangi et al. [44] asserted that self-improvement motivation, entrepreneur’s attitude, networking, and a positive relationship with suppliers are related to sustainability. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Self-improvementpositively and significantly affects enterprise sustainability performance.

2.6. Self-Confidence and Entrepreneurial Competency

Self-confidence reflects a person’s capability to accumulate and employ the resources, skills, and competencies necessary for completing a task [15]. Reverting to RBV, entrepreneurial competency is a highly needed capability for acquiring a firm’s competitive advantage induced by self-confidence [26]. Self-confidence is a strong predictor of general traits, motives, specific skills, visions, strategic actions, and competencies [44]. According to research [45,46], self-confidence represents a necessary attribute for an entrepreneur and influence entrepreneurial intentions. Jordan and Cartwright [47] highlighted that self-confidence, emotional stability, intellectual capability, and openness to new experiences can determine global competencies. Self-confidence can motivate entrepreneurial activities, and when necessary, competencies are acquired [48]. It can also be translated into business and entrepreneurial competencies [49]. Self-confidence, quality of life, and self-realization dictate the formation of valuable orientation to determine an individual’s profession [40]. Erdyneeva et al. [41] noted that personal competencies are associated with relationship skills and self-confidence. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Self-confidence positively and significantly affects entrepreneurial competency.

2.7. Self-Confidence and Enterprise Sustainability

Self-confidence affects an individual’s inclination to take risks along with their acceptance of ambiguity that in turn enables entrepreneurs to handle uncertainty, form good judgments, and deal with failure and success [46]. Drawing on RBV, entrepreneurs with a higher level of self-confidence can facilitate economic, social, and environmental performance [26,29]. Relationship skills and self-confidence are potent predictors of success [41]. Raudeliūnienė, Tvaronavičienė, and Dzemyda [50] stated that communication, planning, problem-solving skills, perseverance, creativity, self-confidence, teamwork, negotiation skills, and foresight are significant to successful business development. Self-confidence is a straightforward antecedent of entrepreneurial knowledge that can predict enterprise performance and growth [51]. Based on the literature review, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

Self-confidence positively and significantly influences enterprise sustainability performance.

2.8. Openness to Change and Entrepreneurial Competency

Openness to change is conceptualized as the willingness to support change with a positive attitude with regards to the possible consequences of adopting such change. We borrow from Murnieks et al. [28] to argue that for entrepreneurs’ motives could change between different phases of their endeavours and hence Openness to Change reflect a crucial construct to study in present context wherein unpredictable changes inheriting the entrepreneurial environments provides a standard setting to investigate changes in entrepreneurial motivation. As stated in RBV, being open to change is an entrepreneurial competency that enables an organization to gain competitive advantages [26]. In a turbulent market condition, individuals with flexibility, openness to change, and skill can facilitate their competencies that enable them to cope with the ever-changing reality [52]. The competencies can be approached through the ability to change and transact business, knowledge of business structure, professional contacts, business issues, flexibility, ethnocentrism, and openness. Moreover, openness to new experience coupled with intellectual capability, self-confidence, as well as emotional stability can determine global competencies [47]. Based on these arguments, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5.

Openness to change positively and significantly affects entrepreneurial competency.

2.9. Openness to Change and Enterprise Sustainability

Entrepreneurship is driven by technology and innovation changes that generate economic growth [15]. RBV explains that openness to change is an entrepreneur’s rare, inimitable, and valuable capability, leading to excellent economic, social, and environmental performance [26,29]. Strategic flexibility is considered as the ability to comply with environmental changes that influence firm performance [53]. Undeniably, openness towards change is associated with job satisfaction, work-related irritation, and withdrawal intention. It is a person’s capability to be open towards innovation, new ideas, as well as independent decisions making [19]. In fact, organizations that manage changes regularly can retain their competitive position. Successful entrepreneurship requires a high level of managerial competencies and openness to learning from other firms, regulators, and consumers. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6.

Openness to change positively and significantly affects enterprise sustainability performance.

2.10. Pull Factors and Entrepreneurial Competency

Pull factors denotes entrepreneurial motivators that attract people to explore business opportunity. According to Haynie and Shepherd [54] motivations to become entrepreneurs is derived from pull factors. RBV states that unique resources can mobilize the formation of specific capabilities that ensure better performance [26]. Undoubtedly, pull factors are valuable resources that form the entrepreneurial competencies required for running a successful business. These factors can be considered as unforced personal desires that transform competencies to venture into entrepreneurship [19]. It is posited that pull factors bring about entrepreneurial motives to select, drive, and direct behaviors and achieve goals that are different from others. Specifically, career-related pull factors can guarantee competencies required for bridge employment. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7.

Pull factors positively and significantly influence entrepreneurial competency.

2.11. Pull Factors and Enterprise Sustainability

As suggested by RBV, firms within the same sector may vary in performance using unique firm-specific resources [26]. In other words, pull factors are individual resources that determine a firm’s economic, social, and environmental performance. These factors are associated with entrepreneurial opportunities required for accomplishing business performance [55]. Buhalis and Main [3] mentioned that pull factors result from governmental, economic, and social influence that “pull” advanced technologies, which cause sustainable performance. Since environmental performance is a cornerstone of sustainability, a firm’s decision to introduce eco-innovation and environmentally friendly products can be influenced by pull factors [56]. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 8.

Pull factors positively and significantly influence enterprise sustainability performance.

2.12. Need for Achievement and Entrepreneurial Competency

Need for achievement could be worded as a desire to perform better for one’s inner feeling instead of prestige or societal acceptance [57]. It is known that entrepreneurs possess greater achievement motivation than others and hence this construct is significantly relevant for present context [58]. Consistent with RBV, the need for achievement represents a valuable unique resource that forms specific competencies required for operating a successful business [26]. Entrepreneurs with a need for achievement are interested to engage in business activities and build up their competency [57]. Ahmad et al. [13] highlighted that personal competency can be reflected by the confidence level, the capability to realize goals, determination, desire to overpower obstacles, determination to achieve goals, and action-oriented great need for achievement. Carraher, Buchanan, and Puia [59] noted that the dynamics of achievement related to motivation are important to promote competencies and participate in entrepreneurial activities. Additionally, Murnieks et al. [28] mentioned that self-regulatory mechanisms may develop strong motivation among entrepreneurs. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 9.

Need for achievement positively and significantly affects entrepreneurial competency.

2.13. Need for Achievement and Enterprise Sustainability

RBV explains that organization within a sector may vary in performance because of their firm-specific capabilities [26]. This means that need for achievement is a rare and inimitable capability that ensures a firm’s outstanding performance. According to Carraher et al. [58], the need for achievement is important for both entrepreneurs and economic development. Vliet, Born, and Molen [60] found that the need for power, need for achievement, and need for affiliation are associated with work performance and social wellbeing. However, Parboteeah, Addae, and Cullen [61] implied that the need for achievement values individuals who can perform, translating that performance orientation negatively corelates to the propensity of supporting sustainability initiatives. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 10.

Need for achievement positively and significantly affects enterprise sustainability performance.

2.14. Entrepreneurial Competency and Enterprise Sustainability

Enterprise sustainability refers to the stakeholder-focused enterprise systems that address integrated performance within environmental and societal restrains [42]. RBV categorizes entrepreneurial competencies as valuable skills, knowledge, and abilities that can ensure high economic, social, and environmental performance [12,26,29]. Enterprise sustainability for small businesses is developed from core competences [61,62]. For micro and small enterprises to survive, the owners must own a quality skillset [63,64]. In a nutshell, developing businesses that are driven by sustainability require competent and innovative entrepreneurs [65]. Hence, we draw the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 11.

Entrepreneurial competency positively and significantly affects enterprise sustainability performance.

2.15. The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Competency

As we considered self-improvement, self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, and need for achievement as dimensions of entrepreneurial competency, entrepreneurial competency is expected to mediate the association between self-improvement, self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, and need for achievement, as well as enterprise sustainability. Based on RBV, self-improvement, self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, and need for achievement are rare, inimitable, and valuable resources that initiate entrepreneurial competency to improve economic, societal, and environmental performance [26,29]. Rehman et al. [66] found entrepreneurial competencies mediate the effect of selected antecedents on business performance, suggesting a possible mediating role of competency in present context. Additionally, Al Mamun and Fazal’s research [67] demonstrated the importance of entrepreneurial competency in mediating the links between a number of variables of entrepreneurial orientation and company success, which indicates that competence could mediate the effect of identified dimension on enterprise sustainability. Recently, Al Mamun et al. [22] further confirmed that entrepreneurial competencies have a substantial mediating influence on the association between certain entrepreneurial traits and firm performance. Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 12a.

Entrepreneurial competency significantly mediates the association between self-improvement and enterprise sustainability performance.

Hypothesis 12b.

Entrepreneurial competency significantly mediates the link between self-confidence and enterprise sustainability performance.

Hypothesis 12c.

Entrepreneurial competency significantly mediates the association between openness to change and enterprise sustainability performance.

Hypothesis 12d.

Entrepreneurial competency significantly mediates the association between pull factors and enterprise sustainability performance.

Hypothesis 12e.

Entrepreneurial competency significantly mediates the link between need for achievement and enterprise sustainability performance.

3. Methodology

We used a cross-sectional design and collected quantitative data through interviews. The sample was low-income households from Kelantan, Malaysia. The state of Kelantan has a total of 10 districts; only 9 were focused on in the study as the remaining one was the capital: Kota Bharu. The reason for this is that Kota Bharu’s mean and median income value is higher compared to other districts. The list of these low-income households was obtained from two developmental organizations: ‘Majlis Amanah Rakyat’ and ‘Majlis Agama Islam dan Adat Istiadat’. From a list of 2795 micro-entrepreneurs, 425 were randomly selected to identify potential respondents using a table of random numbers from nine districts in Kelantan, Malaysia. The data collection took place from September 2017 until November 2017.

3.1. Sample

Based on G*Power 3.1 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany) with a power of 0.95 and an effect size of 0.15, we needed 146 respondents to test the model with six predictors. However, following recommendations for PLS-SEM [68], we collected data from 403 micro-entrepreneurs in Kelantan, Malaysia, in order to avoid complications from having a small sample size.

3.2. Research Questionnaire

The instrument was designed using subjective measures adapted from earlier studies (see Appendix A Table A1). Items for self-improvement were adopted from Carter et al. [36]. To measure self-confidence, items were adopted from McGee et al. [69]. Then, items for openness to change were adopted from two groups of researchers [70,71], while those measured pull factors were adopted from Kirkwood [72]. Moreover, items for need for achievement were obtained from Lynn [73], whereas items for entrepreneurial competency were obtained from Man et al. [74]. Finally, questions to capture enterprise sustainability were derived from Gualandris et al. [75] and Raymond et al. [76]. A seven-point Likert scale (from “1—Strongly disagree” to “7—Strongly agree”) was used for entrepreneurial competency and enterprise sustainability. A five-point Likert scale (from “1—Strongly disagree” to “5—Strongly agree”) was used for all other variables.

3.3. Common Method Variance (CMV)

To minimize CMV, this study ‘informed the respondent that the responses will be evaluated anonymously and there are no right or wrong answers’ [77]. Following Podsakoff et al. [77], we adopted a seven-point Likert scale for the dependent variables and a five-point Likert scale for all independent variables. To identify CMV, a one-factor test was employed to extract one fixed factor from all the variables to explain less than 50 percent of the variance. The analysis showed that one component explained 22.76 percent of the variance. CMV can be detected when the correlation between the constructs is higher than 0.9. The highest correlation between self-confidence and micro-enterprise sustainability was 0.635, which indicated a lack of CMV.

This study further employed a full collinearity test as recommended by Kock [78]. All the study latent constructs regressed on a common created variable. Variance inflation factor (VIF) values were obtained for self-improvement (1.181), self-confidence (1.586), openness to change (1.275), pull factors (1.234), need for achievement (1.115), entrepreneurial competency (1.375), and enterprise sustainability (1.669). All VIF values are less than 5, which indicated a lack of CMV.

3.4. Data Analysis Method

As this study is exploratory in nature with a non-normality issue, variance-based PLS-SEM was employed [79] for data analysis. The results are reported following Hair, et al. [80].

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Profile

As observed in Table 1, of the 403 respondents, 51.6% were male and the rest were female. Many respondents (29.5%) were aged between 31 and 40. Most of them (79.9%) were married. Moreover, 136 of the respondents reported that their firms had been operating for between 6 and 10 years, while 129 of them reported that their firms had been operating for between 1 and 5 years. Most respondents (41.9%) were involved in the service sector.

Table 1.

Profile of the Respondents.

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

Table 2 presents the reliability of the indicators and the descriptive statistics. The low mean value for the need for achievement with a higher standard deviation indicated that the minority of micro-entrepreneurs were not aware of the importance of sustaining their business. Moreover, the larger standard deviation value for micro-enterprise sustainability indicated that the perception of sustainability performance is considerably spread out.

Table 2.

Measurement Model Assessment.

The reliability analysis showed that all the variables achieved a Cronbach’s alpha value of more than 0.7. In other words, all the items were reliable. As depicted in Table 2, the composite reliability values for all the variables were higher than 0.8, which further confirms reliability [80]. The Dillon–Goldstein rho values for all the indicators were higher than 0.7, which confirmed the reliability of all the items. In Table 3, the loading and cross-loading values showed that almost all the indicator loadings were higher than 0.7, which indicated their strong reliability. All the items with standardized loadings lower than 0.7 would be kept for subsequent analysis. As suggested by Chin [81], the indicators with a loading higher than 0.5 should be retained.

Table 3.

Loadings and Cross-Loadings.

In terms of validity, the AVE values in Table 2 were higher than 0.50, which indicates acceptable convergent validity. The cross-loading values in Table 3 illustrate that all the indicator loadings are higher than the total cross-loadings, confirming discriminant validity. Based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion, the AVE for each indicator should be greater than the variable’s highest squared correlation with another. In Table 3, all the variables fulfilled this requirement. Furthermore, the Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) estimates the correlation between variables, paralleling the deattenuated construct score. Based on the threshold value of 0.9, there was no evidence of insufficient discriminant validity. The variance inflation factors (VIF) values for all the variables were lower than 3.3. In this study, multicollinearity was, hence, not a serious issue [81].

4.3. Structural Model Assessment

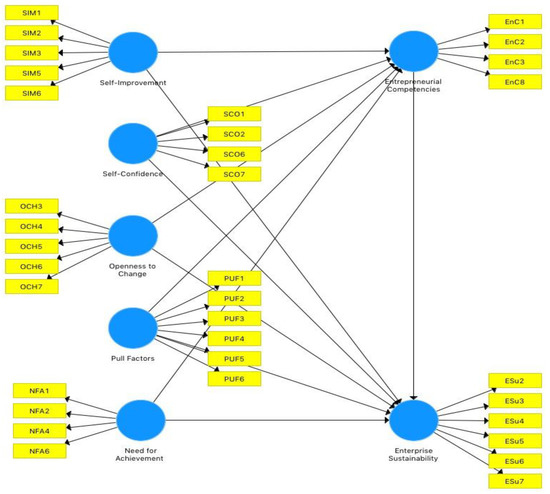

Figure 1 portrays the path analysis diagram for this study. As obeserved in Table 4, the coefficient value for the effect of self-improvement on entrepreneurial competency (Hypothesis 1) was 0.052 with a p-value of 0.283. This indicated a positive but statistically not significant effect of self-improvement motivation on entrepreneurial competency. The f2 value of 0.003 indicated an extremely low effect of self-improvement on entrepreneurial competency. The coefficient value for the effect of self-improvement on enterprise sustainability (Hypothesis 2) was 0.005 with a p-value of 0.92. This showed an insignificant effect of self-improvement motivation on micro-enterprise sustainability. The f2 value of 0.000 indicated an extremely low effect of self-improvement on enterprise sustainability.

Figure 1.

Path Analysis.

Table 4.

Path Analysis.

4.4. Mediation Analysis

The results in Table 5 revealed that self-improvement did not have a significant (p-value = 0.309) indirect effect on enterprise sustainability. Therefore, there was no mediating effect of entrepreneurial competency on the relationship between self-improvement and enterprise sustainability (Hypothesis 12a).

Table 5.

Mediating Effects.

In addition, self-confidence had a positive (p-value = 0.027) indirect effect on enterprise sustainability. This indicated that entrepreneurial competency mediated the relationship between self-confidence and enterprise sustainability (Hypothesis 12b). In terms of openness to change, it had a positive (p-value = 0.001) indirect effect on enterprise sustainability. In other words, entrepreneurial competency mediated the relationship between openness to change and enterprise sustainability (Hypothesis 12c). Furthermore, there was a positive (p-value = 0.015) indirect effect of pull factors on enterprise sustainability. This established the mediating effect of entrepreneurial competencies on the relationship between pull factors and enterprise sustainability (Hypothesis 12d). However, the need for achievement showed an insignificant (p-value = 0.151) indirect effect on enterprise sustainability. This signified that entrepreneurial competency did not mediate the relationship between the need for achievement and enterprise sustainability (Hypothesis 12e).

4.5. Multi-Group Assesment

We analyzed the measurement invariance employing the measurement invariance of composite models (MICOM) procedure for two groups (Group 1. Enterprise established 10 or less years ago, and Group 2. Enterprise established more than 10 years ago). The permutation p-values for all variables exceeded 0.01, which confirmed the partial measurement invariance. Therefore, the study was able to compare the path coefficients between two groups using PLS-MGA. The results (presented in Table 6) of two groups based on Enterprise established revealed no significant differences in all associations hypothesized in this study, except for the effect of the entrepreneurs’ need for achievement on enterprise sustainability.

Table 6.

Multi-group Analysis.

5. Discussion

The sustainability of microenterprises must be the foremost criterion in order to extend their positive socio-economic impacts [23]. Undoubtedly, a sustainable competitive advantage can be achieved when the entrepreneurs can manage their enterprises [13], be capable of making sound financial decisions, and thereby sustain their individual well-being, as well [82]. Therefore, we measured the influence of selected entrepreneurial motivation dimension on competency and enterprise sustainability performance. The findings revealed that self-improvement had a positive effect on entrepreneurial competency, but not enterprise sustainability. Earlier, Anoke et al. [38] found from the Nigerian perspective that self-improvement builds entrepreneurship and facilitates creating entrepreneurial mindset. Zaripova et al. [39], on the other hand, presented that self-improvement is detected in the formation of project-technical competence. Perhaps shaping mindset is one thing and nurturing specific set of skills is other, as reflected by our results that detoured from Anoke et al. [38] and Zaripova et al. [39], suggesting that self-improvement directly enables sustainability performance rathar than improving copetencies to enhance performance. Moreover, self-confidence had a positive effect on entrepreneurial competency. Existing researchers, globally, highlighted much on the role of confidence, as a structure of valuable orientations [40] in influencing entrepreneurial intentions to launch future ventures [44,49] and achieving the goals set in professional activities [39], as well as being an indicator of future success [41]. In line with earlier studies [39,40,41,44,46,47,48,49,50], our results further ascertained that self-confidence could effectively sharpen entrepreneurial competencies and improve economic, social, and environmental performance of micro-enterprises.

The result revealed that openness to change had a positive effect on entrepreneurial competency. This finding agreed with existing studies [47,52] which asserted that the ability to accept change could develop skills required for successful entrepreneurship. Moreover, openness to change had a positive but insignificant effect on micro-enterprise sustainability. In other words, openness to change could not facilitate enterprise sustainability through resources and competencies. Furthermore, the finding showed a positive effect of pull factors on entrepreneurial competency. Similarly, pull factors had a positive effect on enterprise sustainability. Pull factors have been credited by earlier studies as being able to determine adaptation of information technologies [3] and explain eco-innovation activities [56]. We extend the earlier findings demonstrating that pull factors could further initiate entrepreneurs to develop entrepreneurial competency and enable micro-enterprises to achieve excellent economic, social, and environmental performance [3,54,55].

Additionally, the need for achievement had an insignificant effect on entrepreneurial competency. This finding differs from the literature as the need for achievement did not necessarily shape the required competencies among micro-entrepreneurs. Interestingly, the findings revealed a positive effect of the need for achievement on enterprise sustainability. This finding translated that desire to achieve an improved economic, social, and environmental performance across the sample of the present study. Finally, this study found a positive effect of entrepreneurial competency on enterprise sustainability. According to Moore and Manring [62], rapid growth and disruptive innovations are being achieved by SMEs using core competencies. On the other hand, Mindt and Rieckmann [65] argued that the transformation of economic systems for sustainable development involves sustainability-oriented enterprises with competent owners. In line with several past studies [61,62,64], our findings put forward emipirical evidence to confim that entrepreneurial competencies of micro-entrpreneurs, as a specific set of skills, indeed enhance the economic, social, and environmental performance of micro-enterprises. In terms of the mediating effect, the findings showed an indirect effect of self-confidence, openness to change, and pull factors on enterprise sustainability. As noted in RBV, the finding indicated that self-confidence, openness to change, and pull factors were considered as entrepreneurial competencies that help achieve economic, social, and environmental performance [26,29].

6. Implications and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Successful and sustainable entrepreneurship requires a high level of managerial competency in small firms. Theoretically, we answer the call of Joddar [23] for in-depth evaluation of desired impacts on microenterprise development, thereby extending the current literature on microenterprise sustainability. This study contributed by examining the effect of multiple motivational dimensions on entrepreneurial competency and sustainability performance in a single holistic framework, thereby offering a nuanced understanding of the interplay between competencies, motivational dimensions, and sustainability performance. Moreover, we extend the related conceptual investigations [2,12] by forwarding empirical evidence portraying the interactions between motivational dimensions, competencies, and sustainability performance. Furthermore, drawing data from Malaysia, we address the gap of non-western studies [21] by adding the emerging economy’s perspective to the literature. This study contributed specifically to RBV by studying the influence of entrepreneurial motivation on competency and enterprise sustainability.

This study examined both the direct and indirect effect of self-improvement, self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, and the need for achievement on enterprise sustainability. The path analysis and mediation test suggest that both self-confidence and pull factors are capabilities that affect enterprise sustainability directly and indirectly. Openness to change could facilitate enterprise sustainability through entrepreneurial competencies. Another interesting discovery was that the need for achievement was found to influence enterprise sustainability positively without the development of entrepreneurial competency. Thus, these findings could enhance our understanding of psychological motivators and the subsequent effects on competencies development that are expected to facilitate enterprise sustainability.

6.2. Managerial Implications

To discuss practical contributions, this study provided insight into entrepreneurial motivators that enhanced competencies development and different aspects of performance. The findings can be useful to advance entrepreneurial endeavors and improve the socio-economic context of micro-entrepreneurs. In addition, policymakers can rely on these findings to reduce low-income households’ economic vulnerability. Policy formulations should be specifically targeted to increase the sustainability level of microenterprises that would pave the low-income entrepreneurs’ households to attain a decent way of living. Relevant organizations could work to improve the self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial competencies by introducing new policies or strengthening existing policies. Avoiding the one-size-fit-all solutions, developmental organizations should design strategies to uplift self-confidence, openness to change, pull factors, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial competencies regionally or locally, as per the requirements and constraints of diverse micro-entrepreneurship sectors. Entrepreneurs who possess these competencies will most likely be successful in sustaining their micro-enterprises and enabling their socio-economic conditions to flourish as a result.

6.3. Conclusions

The primary goal of this study was to examine the effect of diverse entrepreneurial motivational components on entrepreneurial competency and sustainability performance among micro-entrepreneurs, using Malaysia as a data source. Adopting a cross-sectional design, we collected data from micro-entrepreneurs that revealed significant positive effects of self-confidence, openness to change, and pull factors on entrepreneurial competencies. Self-confidence, pull factors, need for achievement, and entrepreneurial competency further influenced enterprise sustainability. The context of Malaysia was used as a data source to understand the emerging economies or non-Western perspective. Hence, findings of the study could be implied to other emerging nations. In terms of limitation, we could not accommodate all possible determinants of enterprise sustainability. At the same time, we could not cover all aspects of enterprise sustainability in this study, which is why we advise future researcher to be careful when interpreting our results. Since we focused on one firm size (i.e., micro-enterprises), this could have minimized the generalizability of the findings. Future studies can explore other variables that deepen the understanding of entrepreneurial motivation, such as push factors, to capture competency and sustainability performance more comprehensively. In order to enhance the generalizability, future works could examine sustainable performance among firms with various sizes and income groups, with geographically dispersed locations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.M.; methodology, A.A.M.; research instrument, S.A.F. and A.A.M.; validation and formal analysis, A.A.M.; investigation, A.A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.F.; writing—review and editing, S.A.F., R.M., A.S.A., M.H.A. and S.S.A.A.S.; English editing, M.T.; Analysis, A.H.A.S. and S.H.A.M.; F.A. and S.A.F. review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The local ethics committee of University Malaysia Kelantan ruled that no formal ethics approval was required in this paper titled, “Entrepreneurial Motivation, Competency and Micro-Enterprise Sustainability Performance: Evidence from an Emerging Economy”, because (a) the data is completely anonymous with no personal information being collected; (b) the data is not considered to be sensitive or confidential in nature; (c) the issues being researched are not likely to upset or disturb participants; (d) vulnerable or dependent groups are not included; and (e) there is no risk of possible disclosures or reporting obligations. This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from respondents who participated in the survey. For the respondents who participated in the survey were asked to read the ethical statement posted at the top of the form (There is no compensation for responding, nor is there any known risk. In order to ensure that all information will remain confidential, please do not include your name. Participation is strictly voluntary and you may refuse to participate at any time) and proceed only if they agree. No data was collected from anyone under 18 years old.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Survey Instrument.

Table A1.

Survey Instrument.

| Code | Questions | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SI—Item 1 | My reason to start a business was to challenge myself. | [35] |

| SI—Item 2 | My reason to start a business was to grow and learn as a person. | |

| SI—Item 3 | My reason to start a business was to lead and motivate others. | |

| SI—Item 4 | My reason to start a business was the power to influence. | |

| SI—Item 5 | My reason to start a business was the need for personal development. | |

| SC—Item 1 | Being a business owner, I am very confident in my ability to estimate the start-up funds and working capital necessary to start a business. | [68] |

| SC—Item 2 | Being a business owner, I am very confident in my ability to estimate customer demand for a new product or service. | |

| SC—Item 3 | Being a business owner, I am very confident in my ability to give a new idea for a product or service. | |

| SC—Item 4 | Being a business owner, I am very confident in my ability to determine a competitive price for a new product or service. | |

| OC—Item 1 | Being a business owner, I am quite reluctant to accommodate and incorporate changes into my work. | [69,70] |

| OC—Item 2 | Being a business owner, I think changes are really necessary. | |

| OC—Item 3 | Being a business owner, I am very enthusiastic to contribute to a new project. | |

| OC—Item 4 | Being a business owner, I think new projects are advantageous for me. | |

| OC—Item 5 | Being a business owner, I think new changes will have positive effect on my customers. | |

| PF—Item 1 | I started a business because of independence. | [71] |

| PF—Item 2 | I started a business because of money. | |

| PF—Item 3 | I started a business because of challenge | |

| PF—Item 4 | I started a business because of achievement. | |

| PF—Item 5 | I started a business because of opportunity. | |

| PF—Item 6 | I started a business because of lifestyle. | |

| NA—Item 1 | Being a business owner, I find it easy to relax completely when I am on holiday. | [72] |

| NA—Item 2 | Being a business owner, I feel annoyed when people are not punctual for appointments. | |

| NA—Item 3 | Being a business owner, I dislike seeing things wasted. | |

| NA—Item 4 | Being a business owner, I find it easy to forget about work outside normal working hours. | |

| EC—Item 1 | Being a business owner, I am able to identify goods or services that customers want. | [73] |

| EC—Item 2 | Being a business owner, I am able to develop long-term trusting relationships with others. | |

| EC—Item 3 | Being a business owner, I am able to negotiate with others | |

| EC—Item 4 | Being a business owner, I am able to apply ideas, issues, and observations to alternative contexts. | |

| ES– Item 1 | Compared to my major competitors, my firm possesses a higher level of environmental performance. | [74,75] |

| ES—Item 2 | Compared to my major competitors, my firm possesses a higher level of quality of life provided to employees. | |

| ES—Item 3 | Compared to my major competitors, my firm possesses a higher level of employee satisfaction. | |

| ES—Item 4 | Compared to my major competitors, my firm possesses a higher level of retention of employees. | |

| ES—Item 5 | Compared to my major competitors, my firm possesses a higher level of social reputation. | |

| ES—Item 6 | Compared to my major competitors, my firm possesses a higher level of investment in society. |

References

- Alshebami, A.S.; Seraj, A.H.A. Investigating the Impact of Institutions on Small Business Creation Among Saudi Entrepreneurs. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 897787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehseen, S.; Sajilan, S.; Ramayah, T.; Gadar, K. An Intra-Cultural Study of Entrepreneurial Competencies and SMEs Business Success in Whole Sale and Retail Industries of Malaysia:-A Conceptual Model. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2015, 4, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Main, H. Information technology in peripheral small and medium hospitality enterprises: Strategic analysis and critical factors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1998, 10, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.S. Psychological Features and Entrepreneurial Intention among Saudi Small Entrepreneurs during Adverse Times. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzing, C.; Chu, H.M. A comparison of the motivations of small business owners in Africa. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2009, 16, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardianti, R.; Inggrid, N.A. Entrepreneurial motivation and entrepreneurial leadership of entrepreneurs: Evidence from the formal and informal economies. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 33, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, N.A.; Aziz, N.N.A.; Halim, R.A. Networking and innovation performance of micro-enterprises in Malaysia: The moderating effects of geographical location. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2017, 25, 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Zainol, N.R.; Al Mamun, A.; Hassan, H.; Rajennd, M. Examining the effectiveness of micro-enterprise development programs in Malaysia. J. Int. Stud. 2017, 10, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seraj, A.H.A.; Fazal, S.A.; Alshebami, A.S. Entrepreneurial Competency, Financial Literacy, and Sustainable Performance-Examining the Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Resilience among Saudi Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabiswa, F.; Mukwa, J.S. Impact of credit financing on human resource development among micro and small enterprises: A case study of Kimilili Sub County, Kenya. Asian J. Manag. Sci. Educ. 2017, 4, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchelmore, S.; Rowley, J. Entrepreneurial competencies of women entrepreneurs pursuing business growth. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2013, 20, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehseen, S.; Ramayah, T. Entrepreneurial competencies and SMEs business success: The contingent role of external integration. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci 2015, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.H.; Ramayah, T.; Wilson, C.; Kummerow, L. Is entrepreneurial competency and business success relationship contingent upon business environment? A study of Malaysian SMEs. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 182–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Nawi, N.B.C.; Zainol, N.R.B. Entrepreneurial competencies and performance of informal micro-enterprises in Malaysia. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Locke, E.A.; Collins, C.J. Entrepreneurial motivation. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2003, 13, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhemachena, C.; Murimbika, M. Motivations of sustainable entrepreneurship and their impact of enterprise performance in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2018, 1, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robichaud, Y.; McGraw, E.; Alain, R. Toward the development of a measuring instrument for entrepreneurial motivation. J. Dev. Entrep. 2001, 6, 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Almobaireek, W.N.; Manolova, T.S. Entrepreneurial motivations among female university youth in Saudi Arabia. J. Bus. Econ. 2013, 14, S56–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazri, M.A.; Aroosha, H.; Omar, N.A. Examination of factors affecting youths’ entrepreneurial intention: A cross-sectional study. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2016, 8, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; van Gelderen, M.; Thurik, R. Entrepreneurial aspirations, motivations, and their drivers. Small Bus. Econ. 2008, 31, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijdenberg, E.L.; Masurel, E. Entrepreneurial motivation in a least developed country: Push factors and pull factors among MSEs in Uganda. J. Enterprising Cult. 2013, 21, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Fazal, S.A.; Mustapa, W.N.B.A. Entrepreneurial traits, competency, performance, and sustainability of micro-enterprises in Kelantan, Malaysia. Int. J. Asian Bus. Inf. Manag. 2021, 12, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joddar, D. Impact of microentrepreneurial activity: A case of Indian economy. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2021, 44, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masama, B.; Bruwer, J. Revisiting the economic factors which influence fast food South African Small, Medium and Micro Enterprise sustainability. Expert J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 6, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bank Negara Malaysia. Circular On New Definition of Small and Medium Enterprise (SMEs). 2014. Available online: https://www.bnm.gov.my/documents/20124/761700/sme_cir_028_1_new.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijenbrink, J.; Spender, J.C.; Groen, A.J. The resource-based view: A review and assessment of its critiques. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnieks, C.Y.; Klotz, A.C.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurial motivation: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Douglas, E.J. Employment or self-employment: A dynamic utility-maximizing model. J. Bus. Ventur. 2002, 17, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurik, A.R.; Carree, M.A.; van Stel, A.; Audretsch, D.B. Does self-employment reduce unemployment? J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. J. Bus. Ventur. 1996, 11, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.A. A decision theory model for entrepreneurial acts. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 17, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praag, C.M.V.; Cramer, J.S. The roots of entrepreneurship and labour demand: Individual ability and low risk aversion. Economica 2001, 68, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M.; El Tarabishy, A.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brännback, M. Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.M.; Gartner, W.B.; Shaver, K.G.; Gatewood, E.J. The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, T.W.; Lau, T. Entrepreneurial competencies of SME owner/managers in the Hong Kong services sector: A qualitative analysis. J. Enterprising Cult. 2000, 8, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoke, A.F.; Nzewi, H.N.; Onu, A.N.; AGAGBO, O.C. Self-Improvement and Entrepreneurship Mindset Among Students’ of Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria. Glob. J. Manag. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 4, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Zaripova, I.M.; Merlina, N.I.; Valeyev, A.S.; Upshinskaya, A.E.; Zaripov, R.N.; Khuziakhmetov, A.N.; Kayumova, L.A. Methodological support for professional development of physical-mathematical sciences teachers, aimed at forming the project-technical competency of technical university students. Rev. Eur. Stud. 2015, 7, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Komelina, V.A.; Mirzagalyamova, Z.N.; Gabbasova, L.B.; Rod, Y.S.; Slobodyan, M.L.; Esipova, S.A.; Lavrentiev, S.Y.; Kharisova, G.M. Features of students’ economic competence formation. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Erdyneeva, K.G.; Nikolaev, E.L.; Azanova, A.A.; Nurullina, G.N.; Bogdanova, V.I.; Shaikhlislamov, A.K.; Lebedeva, I.V.; Khairullina, E.R. Upgrading educational quality through synergy of teaching and research. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2016, 6, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Searcy, C. Measuring enterprise sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2016, 25, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Bateman, T.S. Self-regulation: From goal orientation to job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangi, M.R.M.; Johari, R.J.; Ismail, A.H.; Noor, R.M. Entrepreneurial Sustainability, Creativity and Innovation Environment of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 7370–7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.R.; Locke, E.A. The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kara, A.; Spillan, J.E.; Mintu-Wimsatt, A.; Zhang, L. The Role of Higher Education in Developing Entrepreneurship: A Two-Country Study. Lat. Am. Bus. Rev. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Cartwright, S. Selecting expatriate managers: Key traits and competencies. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 1998, 19, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiggundu, M.N. Entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in Africa: What is known and what needs to be done. J. Dev. Entrep. 2002, 3, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickul, J.; Wilson, F.; Marlino, D.; Barbosa, S.D. Are misalignments of perceptions and self-efficacy causing gender gaps in entrepreneurial intentions among our nation’s teens? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudeliūnienė, J.; Tvaronavičienė, M.; Dzemyda, I. Towards economic security and sustainability: Key success factors of sustainable entrepreneurship in conditions of global economy. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2014, 3, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omerzel, D.G.; Antončič, B. Critical entrepreneur knowledge dimensions for the SME performance. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2008, 108, 1182–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubiak, M.K. Oczekiwania pracodawców wobec kompetencji absolwentów kierunków ekonomicznych. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Sklodowska Sect. H–Oeconomia 2017, 51, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nadkarni, S.; Herrmann, P.O.L. CEO personality, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: The case of the Indian business process outsourcing industry. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1050–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.M.; Shepherd, D. Toward a theory of discontinuous career transition: Investigating career transitions necessitated by traumatic life events. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekpe, I.; Mat, N.; Che Razak, R. Attributes, environment factors and women entrepreneurial activity: A literature review. Asian Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cai, W.G.; Zhou, X.L. On the drivers of eco-innovation: Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C. N achievement and entrepreneurship: A longitudinal study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1965, 1, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, W.H.; Roth, P.L. A meta-analysis of achievement motivation differences between entrepreneurs and managers. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2007, 45, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraher, S.M.; Buchanan, J.K.; Puia, G. Entrepreneurial need for achievement in China, Latvia, and the USA. Balt. J. Manag. 2010, 5, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliet, S.D.J.; Born, M.; Molen, H.V.D. Self-other agreement between employees on their need for achievement, power, and affiliation: A social relations study. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2017, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parboteeah, K.P.; Addae, H.M.; Cullen, J.B. Propensity to support sustainability initiatives: A cross-national model. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.B.; Manring, S.L. Strategy development in small and medium sized enterprises for sustainability and increased value creation. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Z. The difficulties faced by micro and small enterprises in the formal market access: The case in small and micro enterprises in the cities of Makassar and Kabupaten Gowa south Sulawesi. J. Humanit. 2016, 4, 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lateh, M.; Hussain, M.D.; Halim, M.S.A. Micro enterprise development and income sustainability for poverty reduction: A literature investigation. Int. J. Bus. Technopreneurship 2017, 7, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mindt, L.; Rieckmann, M. Developing competencies for sustainability-driven entrepreneurship in higher education: A literature review of teaching and learning methods. Teoría Educ. Rev. Interuniv. 2017, 29, 1–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.U.; Elrehail, H.; Nair, K.; Bhatti, A.; Taamneh, A.M. MCS package and entrepreneurial competency influence on business performance: The moderating role of business strategy. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Fazal, S.A. Effect of entrepreneurial orientation on competency and micro-enterprise performance. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2018, 12, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, W.; Haenlein, M.; Henseler, J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2009, 26, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J.E.; Peterson, M.; Mueller, S.L.; Sequeira, J.M. Entrepreneurial self–efficacy: Refining the measure. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, G.; Buelens, M.; Bouckenooghe, D. Contribution of content, context, and process to understanding openness to organizational change: Two experimental simulation studies. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 147, 607–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Banas, J.T. Predictors and outcomes of openness to changes in a reorganizing workplace. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, J. Motivational factors in a push-pull theory of entrepreneurship. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2009, 24, 346–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R. An achievement motivation questionnaire. Br. J. Psychol. 1969, 60, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, T.W.; Lau, T.; Snape, E. Entrepreneurial competencies and the performance of small and medium enterprises: An investigation through a framework of competitiveness. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2008, 21, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualandris, J.; Golini, R.; Kalchschmidt, M. Do supply management and global sourcing matter for firm sustainability performance? An international study. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, L.; Marchand, M.; St-Pierre, J.; Cadieux, L.; Labelle, F. Dimensions of small business performance from the owner-manager’s perspective: A re-conceptualization and empirical validation. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 468–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. Bootstrap cross-validation indices for PLS path model assessment. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshebami, A.S.; Aldhyani, T.H. The Interplay of Social Influence, Financial Literacy, and Saving Behaviour among Saudi Youth and the Moderating Effect of Self-Control. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).