1. Introduction

There has been severe pressure on manufacturing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) by stakeholders, including regulatory reinforcement authorities, to effectively utilize natural resources and internal dynamic capabilities by taking proactive environmental decisions through mindful strategies and capabilities for improving their environmental performance. Many countries and organizations have obtained and implemented environmentally friendly green strategies and practices to enjoy a competitive advantage and improve their environmental performance [

1,

2].

SMEs are considered a significant pillar of the economy because of their significant contributions toward poverty reduction, economic growth, and employment generation. The SMEs in Pakistan constitute approximately 92 percent of the business establishments, share almost 40 percent of the country’s GDP, contribute approximately 26 percent to the country’s exports from the manufacturing sector, and 79 percent to industrial employment in the country [

3].

Environmental management issues are now not a novel concept, and these are heavily heard and reflected in the corporate world as a big challenge [

4]. Companies throughout the globe value the significance of environmental performance for a successful business and competitive strategy [

5]. Air pollution is one of the worst environmental issues in the South Asian region, especially in Pakistan [

6], that has resulted in the worst quality of life [

7]. The reasons for the worst air quality in Pakistan are transportation emissions, solid waste burning, and particularly industrial emissions. In Pakistan, this is due to non-strict compliance with environmental regulations and policies concerning manufacturing firm practices freely allowing environmental degradation [

8]. SMEs struggle in devising mindful environmental strategies because mainly their focuses are on making a profit instead of taking care of the environment [

9,

10,

11]. Devising proactive environmental strategies with green mindfulness by SMEs, such as strict environmental regulations beyond basic compliance, high prioritization and importance of environmental issues, effective management of the environmental risk of daily operations, and overall leading the industry toward the status of environmental protection [

12] can enhance their environmental performance.

The mindful attitude in devising proactive environmental strategies for manufacturing SMEs in Pakistan warrants investigation, because the combined environmental impact of the manufacturing SME sector could outweigh the overall health and biodiversity [

13], stability of the global economy [

14], and their environmental performance [

15,

16]. There is paucity and difference of opinion in the relationship between proactive environmental strategies and environmental performance. Such studies by [

17,

18,

19] are in the favor of the positive significant relationship between proactive environmental strategies and environmental performance. However, there exists other studies that do not favor the direct relationship [

20,

21,

22].

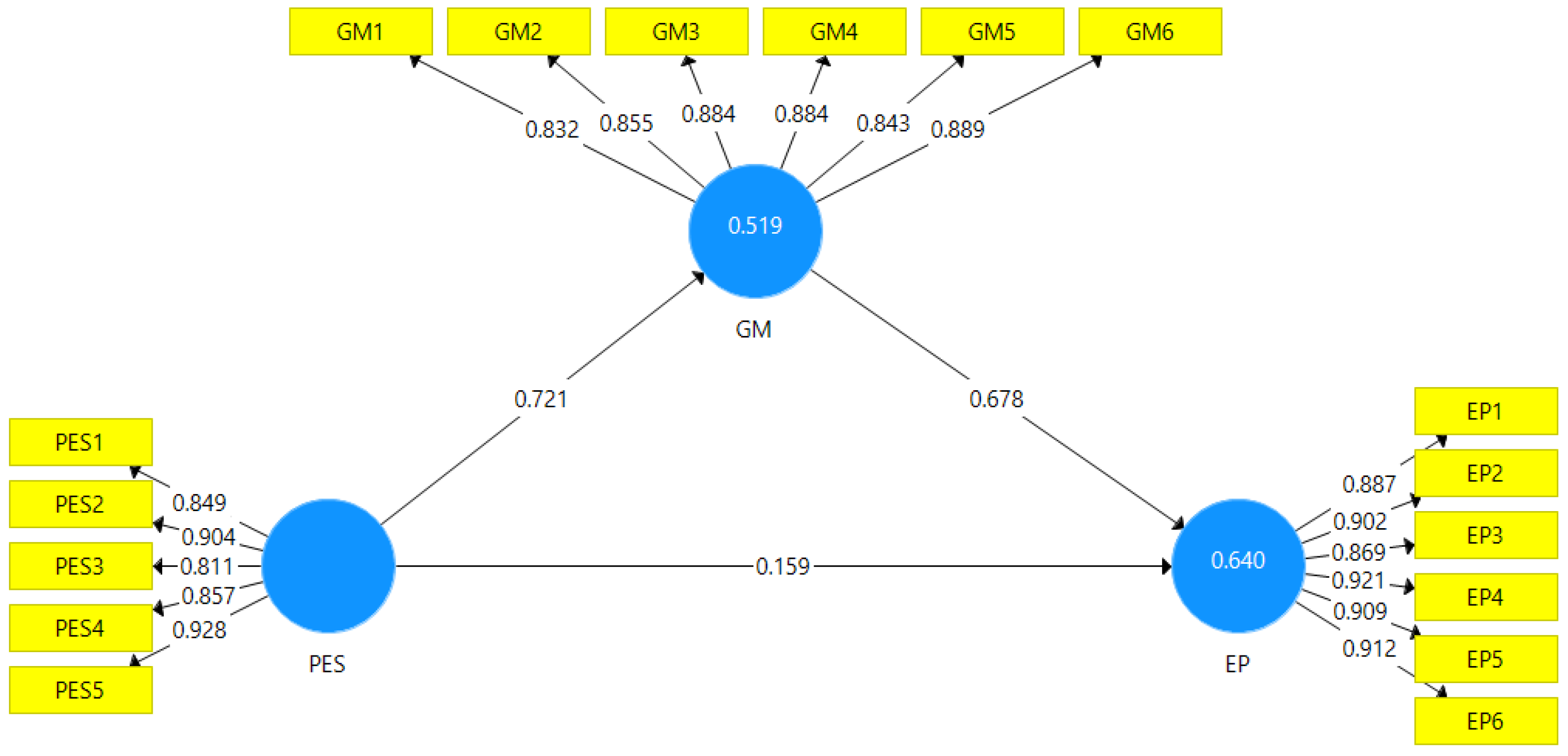

Hence, the main purpose of this study was to empirically explain the influence that proactive environmental strategies has on the firm’s environmental performance and how mindful attention toward environmental management can mediate the relationship between PES and EP. In this sense, this study contributes to the existing literature on PES in three ways. First, we propose a theoretical model to evaluate the impact of PES, and GM on the firm’s environmental performance. Second, this study evaluates the direct and indirect effects of PES on the firm’s EP. Third, this work analyzes this relationship from the perspective of Pakistani SMEs.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the theoretical framework and hypotheses development.

Section 3 describes the materials and methods, discussing how the data was collected and analyzed.

Section 4 presents the data analysis and results. Finally,

Section 5 highlights the discussion and conclusion, along with the research limitations and perspectives.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

In a period of unpredictable change, the dynamic capability view (DCV) explains how a firm develops, incorporates, and reconfigures its internal and external resources [

23,

24]. The dynamic capability framework builds a theory to understand a firm’s performance and to sustain a competitive advantage, especially when organizations face rapidly changing environmental conditions [

24]. The dynamic capability as an extension of the resource-based view (RBV) and advocates that organizations with resources that meet the criteria of VRIN; that is, valuable, rare, imitable, and non-substitutable, certainly allows them to accomplish a competitive advantage [

25].

When organizations are mindful of the effective protection of their resources, they can establish stronger control over the organizational resources and culture that ultimately strengthen their strategies, which leads to a better environmental performance [

26]. Furthermore, the overall environmental quality and productivity can be boosted through mindfully green procedures, strategies, and policies over a period [

27].

By applying the logic of DCV in this study, we expect to attain evidence that the complementarity between proactive environmental strategies and mindfulness enables enterprises to deal with rapid environmental changes and improve their environmental performance. Past studies have witnessed the importance of a proactive environmental strategy in enhancing an organization’s overall performance and competitive edge [

4,

28,

29,

30]. But studies have argued that there is still a need for more empirically-based approaches to proactive environmental strategies [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], as no existing models are empirically sufficient [

33] and explain the relationship between PES and EP within the approach of green mindfulness as a dynamic capability.

Scholars have presented a mixed point of view in the context of the commitment of SMEs toward sustainable environmental strategic goals. Most of the time SMEs due to a shortage of money, cannot publicize environmentally friendly products in the market. The adoption of a proactive environmental strategy is very useful to SMEs by enhancing a remarkable improvement in effectiveness and efficient organizational performance. Rehman, Kraus [

35] highlighted that green innovation mediates the relationship between proactive environmental strategies and environmental performance. For improved environmental performance, it is extremely important to have the best operational practices related to greening the environment. For this reason, this environmental philosophy should be integrated into the operations and production functions of a manufacturing unit.

Several scholars have found a positive relationship between multiple constructs of proactive environmental strategies on the environmental performance of Pakistan’s manufacturing SME sectors [

8,

17,

19,

36,

37]. For instance, San Ong, Magsi [

17] reported that an effective formal and informal environmental management control system in the manufacturing industry of Pakistan facilitates a better environmental performance. Suleman, Bokhari [

19] studied ISO 14001 certified firms from the surgical instrument industry of Pakistan and found that corporate environmental strategies mediated the relationship between environmental performance and firm performance, and further explored that the corporate environmental strategies significantly influenced firm performance at the firm level.

The integration of environmental strategies into the organizational culture is an important phenomenon in the industries of Pakistan. The involvement of top management in the coordinated activities and recording of unorganized decisions into better environmental ideas supports the organizational culture toward a better environmental performance. The study of Shah and Soomro [

20] on the predictive power of proactive environmental strategies on manufacturing firms of Pakistan discovered that there was no direct link between proactive environmental strategies and environmental performance, but the internal green integration significantly improved.

The contradictory findings of empirical research studies on environmental strategies and environmental performance showed an uncertain behavior, and the relationship still needs to be explored further to highlight insights into how organizations may benefit and realize a better environmental performance by proactively setting better environmental strategies to be competitive. Therefore, based on the literature reviewed on proactive environmental strategies and environmental performance we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). There is a significant positive relationship between Proactive Environmental Strategies and Environmental Performance.

Mindfulness is defined as “the way people or organizations reflect, collect information, perceived the world around them, and are thus motivated to change their perspective under the current circumstances to achieve the desired outcome” [

26]. Boyatzis [

38] perceived the perspective of mindfulness as an important component of resonant leadership, and stated that mindfulness is the capacity to be fully aware of what is going on around us (paying full attention to people, the environment, and events) and inside us (fully aware about the self, body, mind, heart, and spiritual changes).

Green mindfulness implies a state of mindfulness where people or organizations adjust their behavior appropriately to become environmentally informed about their impacts and the sources creating these impacts. Green creativity and innovativeness have become widespread as environmentalism has become more common in the market. Chen, Chang [

39] defined green mindfulness as “a state of conscious awareness in which individuals are implicitly aware of the context and content of environmental information and knowledge”.

The literature about mindfulness in environmental sustainability science is still novel and emerging [

40], specifically, studies that directly link green mindfulness with proactive environmental strategies and environmental performance are scarce. Therefore, this study will contribute to filling this gap. A mindfulness-based organization with specific strategic goals and policies relating to environmental betterment transforms the organization into a greener company along with a differentiated competitive advantage.

In mindful organizations people talk to each other, comfortably share, trust in other people, delegate responsibility with a sense of relief, see the beauty in others and consider the environment first [

41]. Umar and Chunwe [

42] emphasized that green mindfulness helps in translating environmental strategies into environmental performance through quality productivity in energy consumption, water utilization, and waste reduction.

Thus, mindfulness enables organizations to achieve a stronger environmental performance, even if the organization is highly risk averse [

43,

44]. Therefore, an organization is likely to have a greater environmental performance when its mindfulness increases, even when the organization copes well with external pressures. Similarly, when firms have strong intrinsic values and have mindful strategic capabilities for the environment, they are more likely to embrace sound environmental protection practices that improve their safety and environmental performance.

Environmentally friendly policies and systems-oriented organizations enjoy more environmental productivity through mindful dynamism. A visionary and focused strategic pro-environmental behavior is important in following mindfulness pursuits. If an organization lacks a shared visionary environmental strategy, it has no sense of direction and/or purpose for environmental safety and mindfulness [

45].

Based on the above discussion, it can be deduced that mindfulness has a significant role in the relationship between proactive environmental strategies and environmental performance and needs more clarification, specifically in the context of Pakistani SMEs. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed for further examination.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). There is a significant positive relationship between Proactive Environmental Strategies and Green Mindfulness.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). There is a significant positive relationship between Green Mindfulness and Environmental performance.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Green Mindfulness positively mediates the relationship between Proactive Environmental Strategies and Environmental Performance.

The proposed conceptual model for this research is shown in

Figure 1.