How Tourism Industry Development Affects Residents’ Well-Being: An Empirical Study Based on CGSS and Provincial-Level Matched Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Research Hypotheses

3. Research Design

3.1. Data and Variables

3.2. Model Setting

4. Results

4.1. Benchmark Regression

4.2. Robustness Test

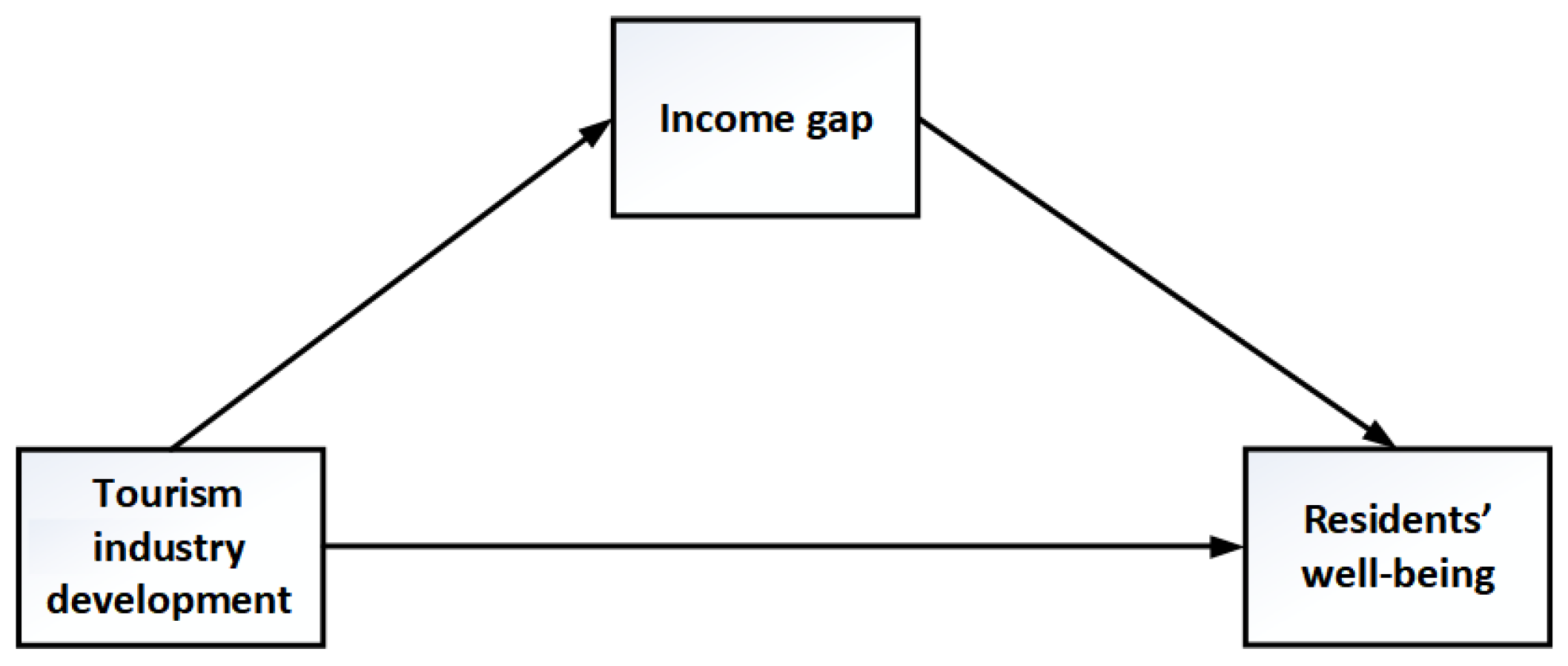

4.3. The Mediating Effect of the Income Gap

4.4. Further Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.2. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeng, H.; Guo, S. “Le”: The Chinese Subject Well-Being and the View of Happiness in China Tradition Culture. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2012, 44, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J. Social Change, Marketization and Chinese People’s Happiness. Southeast Acad. Res. 2020, 1, 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.; Song, L. A Review of Studies on Tourists’ Well-being:Based on Grounded Theory Research Method. Tour. Trib. 2020, 35, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, W. Religious Belief, Economic Income and Subjective Well-being of Urban and Rural Residents. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2016, 7, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F. Gender, Occupation and subjective well-being. Econ. Sci. 2007, 1, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. Education, Income and Happiness of Chinese Urban Residents: Based on the Data of the 2005 Chinese General Social Survey. Society 2013, 33, 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Shi, L. Economic Growth and Happiness: An Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of Easterlin Paradox. Sociol. Study 2017, 32, 95–120, 244. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Li, S. How Can Government Make People Happy? An Empirical Study on the Impact of Government Quality on Residents’ Happiness. Manag. World 2012, 5, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, K. Economic Growth, Pro-poor Spending and National Happiness—Empirical Study Based on China’s Well-Being Data. Economist 2010, 11, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Cao, S. On the Connotation and Ethical Value Guidance of the Happiness Paradox in Tourism Development. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2021, 55, 309–316. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A. Gender and social influence: A Social Psychological Analysis. Am. Psychol. 2016, 38, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ary, D.V.; Biglan, A.; Glasgow, R.; Zoref, L.; Black, C.; Ochs, L.; Severson, H.; Kelly, R.; Weissman, W.; Lichtenstein, E.; et al. The efficacy of social-influence prevention programs versus “standard care”: Are new initiatives needed. J. Behav. Med. 1990, 13, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhong, W.; Hong, Y. Analysis of Influential Factors of Civil Happiness in China: Based on LASSO Screening Method. Stat. Res. 2018, 35, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Deaton, A.; Stone, A. Understanding Context Effects for a Measure of Life Evaluation: How Responses Matter. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2016, 68, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.; Oswald, A. Well-being Over Time in Britain and the USA. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 1359–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praag, B.; Romanov, D.; Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A. Happiness and financial satisfaction in Israel:Effects of religiosity, ethnicity, and war. J. Econ. Psychol. 2010, 31, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Yang, H. Subjective Well-being of Middle School Students. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2006, 20, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Lelke, O. Knowing what is good for you. J. Socio-Econ. 2006, 35, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Frijters, P.; Shields, M.A. Relative income, happiness and utility an explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 95–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Feng, X. Identity, Gender and Happiness—An Analysis Based on Family Level. World Econ. Pap. 2020, 5, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F.; Gan, X. A Review of Western Studies on the Influencing Factors of Subjective Well-being. Inq. Into Econ. Issues 2013, 11, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A.; Oswald, A. Satisfaction and comparison income. J. Public Econ. 1993, 61, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, S. Regulation, Corruption and Happiness: Empirical Evidence from CGSS (2006). World Econ. Pap. 2013, 4, 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Shi, L. Economic Growth and Subjective Well-being: Analyzing the Formative Mechanism of Easterlin Paradox. J. Chin. Sociol. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Su, Y.; Liu, J. National Sense of Happiness in the Economic Growth Period: A Study Based on CGSS Data. Soc. Sci. China 2012, 12, 82–102, 207–208. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T. Relative Deprivation and Social Justice. A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England by W.G. Runciman. Br. J. Sociol. 1966, 17, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; He, L. Uncover the “Easterlin Paradox” of China: Income Gap, Inequality of Opportunity and Happiness. Manag. World 2011, 8, 11–22, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, K.; Sun, J.; Wang, G. The Impact of Income Inequality on Residents’ Well-being—An Empirical Study Based on FS model. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 6, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Li, H. A study on the Influence Mechanism of Income Gap on Well-being. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 11, 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, P.; Li, X. The Well-being Enhancement Effect of Tourism: A Piece of Empirical Evidence by CGSS2015. Tour. Sci. 2019, 33, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R.; Huang, Z.; Bao, J.; Guo, X.; Mo, Y. The Influence of Rural Tourists’ Nostalgia on Subjective Well-being and Recreational Behavior Intention. Tour. Trib. 2022, 37, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, W. Study on the Influence of Hosts and Tourists Conflicts on Residents’ Psychological Well-being in Tourist Destination–Take City Historic Districts in Shandong Province as Examples. Econ. Manag. J. 2014, 36, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. The Impact of Income Inequality on Subjective Well-being: Evidence from Chinese General Social Survey Data. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 2011, 3, 93–101, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. An Economic Analysis of the Output Contribution of Tourism—The Output Contribution and Multiplier Effect of Tourism in Shanghai. Shanghai J. Econ. 2001, 12, 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. Can Tourism Industry Agglomeration Affect Regional Income Gap? Based on Threshold Regression Analysis of Provincial Panel Data in China. Tour. Sci. 2013, 27, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Different Methods for Testing Moderated Mediation Models: Competitors or Backups? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Hou, J.; Zhang, L. A Comparison of Moderator and Mediator and Their Applications. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2005, 2, 268–274. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Z.; Ye, B. Analyses of Mediating Effects: The Development of Methods and Models. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 22, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test the mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.; Hayes, A. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.; Rucker, D.; Hayes, A. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Mackinnon, D. Bayesian mediation analysis. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Xing, Z. Tourism and the Well-being of the Population. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C. Absolute Income‚Relative Income and Subjective Well-being: Empirical Test Based on the Sample Data of Urban and Rural Households in China. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 35, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Measurement | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents’ Well-Being | Very unhappy, unhappy, neutral, happy and very happy, with values of 1–5, respectively | 3.82 | \ | 1 | 5 |

| Tourism Industry Development | Logarithm of total domestic and foreign tourism revenue | 1.41 | 0.57 | 0.12 | 2.56 |

| Income Gap | Gini coefficient | 0.85 | 0.1 | 0.63 | 0.92 |

| Gender | 1 for male and 0 for female | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Age | Natural logarithm of age | 3.83 | 0.37 | 2.83 | 4.63 |

| Marital Status | 1 for married and 0 for others | 0.78 | 0.41 | 0 | 1 |

| Educational Level | Primary school and below, junior high school, vocational high school/ordinary high school/technical secondary school/technical school, junior college, undergraduate and above, with values of 1–5, respectively | 2.24 | 1.25 | 1 | 5 |

| Health Status | The value is 1–5, and the higher the value is, the healthier the individual | 3.52 | 1.12 | 1 | 5 |

| Political Outlook | 1 for Chinese Communist Party members and 0 for others | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Religious Beliefs | 1 for religious belief and 0 for no religious belief | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Social Equity | Very unfair, unfair, neutral, fair and very fair, with values of 1–5, respectively | 3.07 | 1.06 | 1 | 5 |

| Social Trust | Very distrust, distrust, neutral, trust and very trust, with values of 1–5, respectively | 3.44 | 1.03 | 1 | 5 |

| Social Hierarchy | Grades of 1 to 10 from low to high | 4.19 | 1.71 | 1 | 10 |

| Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Ordered Logit | Ordered Probit | |

| Tourism Industry Development | −0.020 *** 1 | −0.063 *** | −0.032 *** |

| Age | −2.414 *** | −7.247 *** | −3.99 *** |

| Age Squared | 0.340 *** | 1.017 *** | 0.560 *** |

| Gender | −0.070 *** | −0.202 *** | −0.111 *** |

| Marital Status | −0.036 *** | −0.078 *** | −0.045 *** |

| Educational Level | 0.024 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.031 *** |

| Health Status | 0.150 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.218 *** |

| Political Outlook | 0.095 *** | 0.276 *** | 0.154 *** |

| Religious Beliefs | 0.066 *** | 0.199 ** | 0.109 *** |

| Social Equity | 0.170 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.244 *** |

| Social Trust | 0.058 *** | 0.163 *** | 0.086 *** |

| Social Hierarchy | 0.106 *** | 0.276 *** | 0.153 *** |

| Model (1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OLS | Ordered Logit | Ordered Probit | |

| Tourism Industry Development | −0.020 *** 1 | −0.063 *** | −0.032 *** |

| Age | −2.414 *** | −7.247 *** | −3.99 *** |

| Age Squared | 0.340 *** | 1.017 *** | 0.560 *** |

| Gender | −0.070 *** | −0.202 *** | −0.111 *** |

| Marital Status | −0.036 *** | −0.078 *** | −0.045 *** |

| Educational Level | 0.024 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.031 *** |

| Health Status | 0.150 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.218 *** |

| Political Outlook | 0.095 *** | 0.276 *** | 0.154 *** |

| Religious Beliefs | 0.066 *** | 0.199 ** | 0.109 *** |

| Social Equity | 0.170 *** | 0.447 *** | 0.244 *** |

| Social Trust | 0.058 *** | 0.163 *** | 0.086 *** |

| Social Hierarchy | 0.106 *** | 0.276 *** | 0.153 *** |

| Model (2) | Model (3) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tourism Industry Development | −0.010 *** 1 | −0.020 *** |

| Industrial Structure | −0.007 | |

| Economic Development | −0.000000146 *** | |

| Financial Development | −0.018 | |

| Human Capital | 0.000000011 *** | |

| Openness to the Outside World | −0.001 *** | |

| Income Gap | −3.126 *** | |

| Age | −2.414 *** | |

| Age Squared | 0.340 *** | |

| Gender | −0.070 *** | |

| Marital Status | −0.036 *** | |

| Educational Level | 0.036 *** | |

| Health Status | 0.024 *** | |

| Political Outlook | 0.095 *** | |

| Religious Beliefs | 0.067 *** | |

| Social Equity | 0.170 *** | |

| Social Trust | 0.058 *** | |

| Social Hierarchy | 0.106 *** |

| Model (4) | |

|---|---|

| Tourism Industry Development | −0.020 *** 1 |

| Income Gap | −3.117 *** |

| Gender | −0.056 |

| Income Gap × Gender | −0.016 |

| Age | −2.414 *** |

| Age Squared | 0.340 *** |

| Marital Status | −0.036 *** |

| Educational Level | 0.024 *** |

| Health Status | 0.150 *** |

| Political Outlook | 0.095 *** |

| Religious Beliefs | 0.066 *** |

| Social Equity | 0.170 *** |

| Social Trust | 0.058 *** |

| Social Hierarchy | 0.106 *** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, C.; Tian, L.; Shan, Y. How Tourism Industry Development Affects Residents’ Well-Being: An Empirical Study Based on CGSS and Provincial-Level Matched Data. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912367

Zhou C, Tian L, Shan Y. How Tourism Industry Development Affects Residents’ Well-Being: An Empirical Study Based on CGSS and Provincial-Level Matched Data. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912367

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Chunmei, Liqi Tian, and Yujun Shan. 2022. "How Tourism Industry Development Affects Residents’ Well-Being: An Empirical Study Based on CGSS and Provincial-Level Matched Data" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912367

APA StyleZhou, C., Tian, L., & Shan, Y. (2022). How Tourism Industry Development Affects Residents’ Well-Being: An Empirical Study Based on CGSS and Provincial-Level Matched Data. Sustainability, 14(19), 12367. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912367